From Cather Studies Volume 6

Rebuilding the Outland Engine

A New Source for The Professor's House

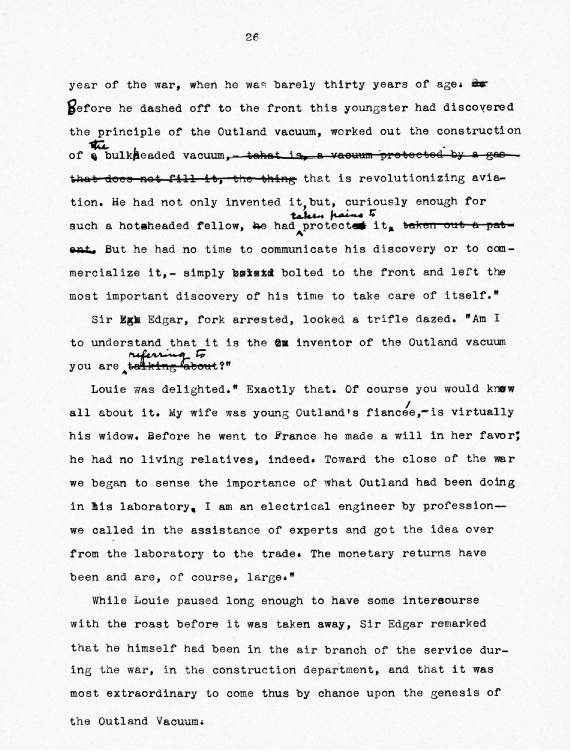

As revealed by the Southwick typescript of The Professor's House,[1] Willa Cather struggled when trying to imagine the specific scientific "principle" that Tom Outland discovers and that Louis Marcellus later incorporates into a highly profitable commodity— the celebrated Outland engine. In the typescript (see fig. 1), Louis awkwardly recounts Outland's successes to Sir Edgar, the English scholar who dines with the St. Peters in chapter 2 of "The Family," as follows: "Before he dashed off to the front this youngster had discovered the principle of the Outland vacuum, worked out the construction of the bulkheaded vacuum—that is, a vacuum protected by a gas that does not fill it, the thing that is revolutionizing aviation" (26). Wisely, Cather scratched out the obfuscating phrase "that is, a vacuum protected by a gas that does not fill it" and made other significant changes to this passage (changes not indicated on the Southwick typescript) later in the revision process. Here are Louie's comments in their more familiar form, as they appear in the tenth printing of the first edition published by Knopf in 1925: "Before he dashed off to the front, this youngster had discovered the principle of the Outland vacuum, worked out the construction of the Outland engine that is revolutionizing aviation" (42). In tracing Cather's difficulties with this passage, we see that the Outland vacuum was just that—a gap within the narrative, a space or void where Cather's ordinarily sure-footed imagination could find no purchase. Thus, the more she attempted to describe it, the more obscure the vacuum became—with stylistically awkward results. In the end, her decision to condense Louie's remarks, in a way that leaves the specifics of Outland's discovery a mystery, displays her artistic instincts at their best and provides a compelling illustration of the compositional techniques advocated in her essay "The Novel Démeublé."

One intriguing detail, however, remains intact throughout the textual history of The Professor's House (or, rather, the limited portion of that history to which we have access), namely, the link between Outland's shadowy discovery and World War I-era aviation. For example, both the Southwick typescript and the first edition indicate that Outland's innovation is "revolutionizing aviation" (42). Though phrased differently in the two versions, Sir Edgar's connection to aeronautical technology is consistent as well. In the typescript, he recognizes Outland's name because "he himself had been in the air branch of the service during the war" (26). In the first edition, Cather makes the same point about the Englishman's wartime affiliation and his prior knowledge of Outland but tightens her military terminology, substituting "Air Service" (meaning, presumably, the Royal Air Force) for "air branch of the service." Moreover, both texts place Sir Edgar in the "construction department" of the RAF, where, it follows, he would have acquired an intimate familiarity with the mechanism bearing Outland's name. Based on this evidence, it appears that Cather's uncertainty regarding the specific nature of Outland's discovery existed side by side with a desire, perhaps sustained from the very beginning of her work on The Professor's House, to link Outland's research to early-twentieth-century aviation.

Why aviation? Or, more specifically, why military aviation?

What might have inspired Cather to select this particular application

for Outland's genius? This essay will address these questions

by offering a prototype for the Outland engine, a prototype that

Cather's readers in 1925 would almost certainly have recognized.

Once set alongside this possible source of inspiration, Louie's contribution

to the Allied war effort, which he achieves by appropriating

Outland's discovery, suddenly emerges as an anything but

arbitrary detail in Cather's text. Indeed, Cather's decision to tie

Louie's wealth (and Outland's reputation) to a World War I-era

aircraft engine stands, when seen in this light, as one of her most

inspired artistic touches; arguably no other kind of machine would

Fig. 1. Cather's introduction of the Outland engine in the Southwick typescript. Philip

L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and Special

Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

have worked so well in a novel focused on the intersection of technological

innovation, war, and commerce.[2]

Fig. 1. Cather's introduction of the Outland engine in the Southwick typescript. Philip

L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and Special

Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries.

have worked so well in a novel focused on the intersection of technological

innovation, war, and commerce.[2]

At first sight, the notion of locating a prototype for the Outland engine, a fictional breakthrough in aviation propulsion, appears dubious. Simply put, no corresponding breakthroughs occurred in actuality, at least not during World War I. As James Woodress and Kari Ronning remark in their explanatory notes for the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition of The Professor's House, "There were no radical inventions that revolutionized the aviation industry during the forty years that followed the Wright brothers' first flight in 1902" (344). Although by 1926, one year after the publication of Cather's novel, Pratt and Whitney had devised an engine "fifty times more powerful than the one used by the Wright Brothers," aeronautical engineers still relied upon piston-driven motors to deliver power to propellers (345). In other words, increased horsepower, which boosted airspeed and allowed for the construction of larger aircraft, represented the main achievement of aviation science in the 1910s and 1920s; little else, in terms of the fundamentals of lift and propulsion, separated World War I-era airplanes from the Wright Flyer. Thus, it would seem that the Outland engine, credited in The Professor's House with "revolutionizing aviation," is a matter of pure imagination on Cather's part—a rare instance when her creativity operated independently of any prototype.

As it turns out, however, the Outland engine is not entirely divorced from Cather's milieu, for an American aircraft engine did receive extensive press coverage during the First World War, as well as numerous (if undeserved) accolades for its purportedly groundbreaking design and topnotch performance. This supposed mechanical marvel was the so-called Liberty engine, one of the United States' most publicized technological contributions to the Allied war effort.

Like the Outland engine, the product of a cowboy turned scientific researcher, the Liberty engine enjoyed a colorful creation story. The circumstances surrounding its development were, in fact, legendary—thanks in part to a government propaganda effort aimed at boosting public confidence in American technological know-how. In May 1917, just one month after the American declaration of war, a new federal task force known as the Aircraft Production Board summoned top engine designers J. G. Vincent (of Packard Motors) and E. J. Hall (of the Hall-Scott Motor Company) to Washington DC. The task set before these engineers was a formidable one: to devise, as quickly as possible, an American aircraft engine that would rival, if not surpass, those designed under wartime pressures by Great Britain, France, and Germany. More specifically, the board required an engine that would "be light in proportion to power" and, perhaps most importantly, "adaptable to quantity production"—adaptable, in other words, to the neoefficient practices of mass production that were then revolutionizing the American automobile industry (Knappen 77). Anticipating, like most Allied war planners, that the Great War would last into 1919 (if not beyond), the board hoped to build the fledgling American Air Service, which had received almost no funding prior to 1917, into the most advanced organization of its kind, complete with American-made aircraft numbering in the thousands. Designed with high-speed production methods in mind, the engine created by Vincent and Hall would, the board hoped, literally supply the power for this aerial juggernaut.

On May 29, 1917, board officials brought the two engineers, who had never met before, together in Suite 201 of the Willard Hotel in Washington DC, where the pair were asked to remain until they produced a set of basic blueprints. According to legend, Vincent and Hall worked nonstop from the afternoon of May 29 until 2:00 a.m. the next night and slept only sporadically thereafter. Whatever assistance they required, the board provided. Metallurgists and draftsmen soon filled the suite—along with representatives of other Allied governments, eager (now that the United States was no longer a neutral power) to share confidential drawings of their own aeronautical machinery. After just five days, Vincent and Hall left the Willard Hotel with the design for the new engine in hand.

Subsequent production moved just as swiftly. In July 1917, less than two months after the Liberty engine's birth on paper, an eight-cylinder prototype, assembled by the Packard plant in Detroit, arrived at a test facility in Washington DC. One month later, researchers tested and approved the twelve-cylinder version ultimately adopted by the U.S. military. In the fall of 1917, assured of the new engine's sound design, the War Department placed an order for a staggering 22,500 Liberty engines and divided the contract among several automobile manufactures, including Packard, Lincoln, Ford, and General Motors. The decision to assign aircraft engine production to American car companies, as opposed to the fledgling American aviation industry, soon met with controversy; however, the Aircraft Production Board defended this policy based on the enormous scale of the automobile industry's existing facilities and its established methods of high-speed mass production.

Detroit proved eager to justify the board's confidence. Asked to supply cylinders for the new engine, items traditionally manufactured through a difficult and time-consuming process, engineers at Ford swiftly devised an improved technique for cutting and pressing steel; as a result, cylinder production rose almost overnight from 151 units per day to more than 2,000 (Knappen 119). Not to be outdone, Lincoln Motor Company completed the construction of a new plant in record time, devoted the entire structure to Liberty engine production, and assembled 2,000 engines in twelve months (104). By the time of the Armistice, the six automobile companies under contract with the War Department had manufactured 13,574 Liberty engines and had reached a combined production rate of 150 engines per day (Hudson 16). Amid the generally disappointing record of American wartime production—by war's end the American army still relied primarily upon with French-made tanks, artillery, and machine-guns—the plentiful Liberty engine stood out as a vindication of American manufacturing methods. But whether the engine actually worked remained a matter for debate, as we will see, as the testimony of pilots clashed with that of industrialists.

Not surprisingly, given its propaganda appeal as a supposed triumph of American engineering and modern mass production, the Liberty engine attracted no fewer than sixty-seven articles and editorials in the New York Times between July 1917 and December 1918, and thus it is likely that Cather, an avid newspaper reader, knew the engine's history in some detail.[3] Among the Times articles that she may have perused are the following eye-catching headlines: "New Motor Developed by Aircraft Production Board," "Perfection of Liberty Motor Announced by Sec. Baker," "Liberty Motor Called Best in World by Experts at Convention of Society of Automotive Engineers," "J. M. Eaton Asserts that German Spies Are Delaying [Liberty Engine] Production," "Battleplanes Equipped with Liberty Motors Are On Way to France Five Months Ahead of Schedule," and "Report of Wholesale Liberty Motor Production Called Bluff by A. H. G. Fokker in Interview Printed in Berliner Zeitung." I cannot say with absolute certainly that Cather read these pieces—or even noticed them. However, the subject of military aviation did attract her, as evidenced by her personal copy of Victor Chapman's Letters from France, the posthumously published correspondence of a volunteer airman: inside the front cover Cather pasted several news clippings related to famous World War I flyers.[4] In addition, her sensitive and credible portrayal of the pilot Victor Morse in One of Ours suggests a deep-seated fascination with the world's first air war, a fascination that may have prompted her to scan at least part of the extensive coverage devoted to the Liberty engine in the New York Times.[5]

Textual evidence in The Professor's House of a link between the Liberty and Outland engines takes two forms: scattered details that appear to have their origin in the real-life story of Vincent and Hall's invention and broad thematic parallels. One especially striking example of the former is Sir Edgar's encounter with the Outland engine while working in the RAF construction department. At first sight, this detail seems rather preposterous (and thus in keeping with the aura of strangeness and the fantastic that surrounds Tom Outland in general). What is an American motor doing in the hands of the RAF? As it turns out, the history of the Liberty engine, which Cather has in this instance explicitly appropriated, provides the answer. In June 1918, the British Air Ministry approved the adoption of the American-made Liberty as an alternative to the high-power aircraft engine manufactured by Rolls Royce, and by September 1918, RAF pilots had field-tested enough of the American imports to conclude (perhaps erroneously) that they functioned at least as well as the Rolls model. As a result, thousands of Liberty engines went into service aboard British aircraft, as well as those of other Allied air services—a fact that Cather's original audience may have considered when evaluating the plausibility of the Outland engine's international success.

Readers of The Professor's House in 1925 perhaps also recognized the specter of the Liberty engine, now in a wispier thematic form, amid Cather's oblique account of Louie's war profiteering. Indeed, the controversy that raged throughout 1918 over the quality of the Liberty engine and the motives of its Marsellus-like manufactures is a significant, perhaps even central, "thing not named" in The Professor's House. Among war-related machines produced in America during the First World War, the Liberty engine proved one of the most vulnerable to charges of profit-seeking and opportunism on the part of its creators; it was second in this regard only to the American-built aircraft for which it was primarily designed—the De Haviland 4 (or DH-4, also nicknamed the "flaming coffin"), a vehicle whose questionable airworthiness became the subject of congressional inquiry (Fredericks 158). Two years after the war, industrial journalist Theodore Macfarlane Knappen vigorously defended the Liberty engine and its manufactures in his popular book Wings of War, a semi-official history of the American contribution to Allied air power. By Knappen's account, the Detroit auto kings were selfless patriots, indifferent to profit, indeed even willing to work at a loss while helping to win the war. The Packard Company, for example, nobly "sacrificed itself for all" by expensively retooling its Liberty engine assembly lines (116). "It is easy," Knappen writes, "to talk of profiteering and to say that all who fought in the war with the forge and the machine fought only for gain . . . but patriotism and the desire to serve at any cost were the dominating motives with thousands of our manufactures. In no effort was this better exemplified than in the conception and production of the Liberty motor" (120). As for the Liberty engine itself, Knappen underscored the reliability of this "great motor" by citing its flawless performance on several celebrated postwar flights, including Capt. E. F. White's nonstop flight from Chicago to New York in April 1919 and the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic, performed by USN Commander Read later that same year. These aeronautical feats were made possible, Knappen insisted, by the same "regular, 'run-of-factory' " engine installed in thousands of Allied aircraft during the war (114).

Later histories offer a different view, both of wartime Detroit and of the Liberty engine. For example, in The Canvas Falcons (1970), a general history of World War I aviation, Stephen Longstreet maintains that profit, not patriotism, motivated contract-holding companies, and he cites the Liberty engine, "a shoddy item," as an example of the way that "American war orders made millionaires, but hardly equipment fit to use overseas" (244). Likewise, in his classic history of the AEF, The Doughboys (1963), Laurence Stallings paints a largely negative picture of Vincent and Hall's design. According to Stallings, Liberty engine contracts were a financial bonanza for Detroit but only because the engine's operators, who had little confidence in the contraption, were stuck with it. Airmen in France and England, he remarks, claimed the "new engine had a hundred bugs. Less pessimistic pilots said [it] only had seventy-five bugs" (250).

A more balanced, though far from flattering, assessment appears in James J. Hudson's Hostile Skies (1968), a history of the American Air Service in World War I. Hudson praises the Liberty engine as an essentially "fine high-horsepower aircraft power plant" but acknowledges the various defects—many of them corrected by the war's end—that resulted from the motor's hasty development and production. Indeed, Hudson recounts that when fitted onto the notorious DH-4, the engine delivered especially questionable performance, as observers learned during stateside test trials (staged while the DH-4was already entering service overseas) in the spring of 1918. The assortment of mechanical glitches —some attributable to the plane, some to the engine—recorded at these trials by Col. Henry H. Arnold, head of the Division of Military Aeronautics, resemble silent film-era slapstick: On April 24th a full throttle test for endurance was made but due to the auxiliary gravity tank failing to function, the plane was forced down after one hour and fifty-two minutes in the air. During this test the radiator shutters broke due to vibration; shock absorber rubbers on the landing gear were stretched too tight, were not large enough, and had to be changed. The radiator shutters would not remain open in the air. The main gasoline tank was leaking badly. On April 25th a half throttle test was made. It was found necessary to descend at the end of two hours due to the fact that five spark plugs had been broken. (qtd. in Hudson 18) Several days later, the comedy turned deadly as "the test plane went into a spin from 300 feet" and killed the two men aboard (Hudson 18). Although the various mechanical failures associated with Liberty-equipped DH-4s arguably derived more from the airplane than from its power plant (the disastrous placement, for example, of the DH-4's fuel tank in an exposed position between the pilot and observer had nothing to do with the quality of the aircraft's motor), the Liberty engine's association with the "flaming coffin" did little to help its reputation. Ultimately, Vincent and Hall's motor emerged from the Great War under a cloud of ambiguity, a symbol of American engineering and production genius to some, an icon of opportunism to others—a description that also fits the fictional power plant located at the heart of Louie Marsellus's commercial success and Tom Outland's posthumous reputation.

The story of the Liberty engine, then, may have inspired Cather in at least three ways. First, as the only example of American-produced hardware (apart from artillery shells) to see widespread use by other Allied armies, the Liberty engine perhaps provided the basis for creating an American wartime invention that would be well known among multiple nationalities—in sad and ironic contrast, of course, with Outland's largely forgotten (but arguably more admirable) achievements as a self-trained archeologist. Second, the production history of the Liberty would have offered Cather a compelling narrative of wartime big business. In the men who conceived the Liberty engine in just five days, as well as those who oversaw its ultra-accelerated mass production, are displayed all the confidence, energy, and resourcefulness that Cather attributes to Louis Marsellus, an engineer/entrepreneur whose pep and can-do spirit would have been right at home in wartime Detroit. And, third, the controversy surrounding the Liberty engine (and, by extension, the DH-4) may have turned Cather's thoughts to the fuzzy morality of wartime contract procurement. Did the American auto industry "sacrifice itself," as Knappen claims, for the sake of the country? Or was money the real engine at work in Detroit? The Professor's House raises similar questions against the same wartime industrial backdrop. Is Louie, who patents a dead man's design, a patriot? Or a profiteer? Did Louie see the value of the Outland engine in terms of its benefit to the Allied war effort? Or its benefit to himself? In these three ways, the story of the Liberty engine apparently offered Cather a rich blend of ideas and issues from which to draw.

The various connections that I have posited do not, however, suggest that Cather built her fictional engine entirely from historical parts. Indeed, she appears to have inverted much of the Liberty engine narrative, in effect, writing against or away from her prototype. For example, while the Outland engine employs a new discovery in the field of physics (or is it chemistry?), one so divergent from established understanding that Cather can only call it a "vacuum" and leave it at that, the Liberty engine was anything but experimental. As Knappen explains, the Aircraft Production Board steered Vincent and Hall away from innovations that might slow down the engine's trials and subsequent production. The new engine, the board insisted, "must embody no theory or device that had not already been proved in existing engines. . . . It was not to be an invention, but the simplest and most powerful composite of the best known practice" (77). In other words, Louie Marselluses, not Tom Outlands—practical engineers, not romantic inventors—created the Liberty engine. Vincent and Hall offered nothing visionary in their design; instead, they devised what Knappen praised as the ultimate "producer's engine" (83), subordinating creativity and boldness to the requirements of accelerated mass production. It is also important to note that Outland's invention has none of the "bugs" reported by the Liberty engine's unfortunate operators. Although Mrs. Crane and others question the ethics of Louie's actions in 1917, when he discovers and then takes possession of Outland's scientific "papers," no one in The Professor's House contests the quality of the engine that Louie ultimately manufactures—or the genius behind its design. By imagining a truly innovative aircraft engine, one untarnished by accusations of overly expeditious design and production, Cather did more than modify her prototype: she nearly created its antithesis.

More concrete evidence pointing to a link between the Outland and Liberty engines is, I will admit, unavailable—at least for the moment. As far as we know, Cather did not mention the federal Aircraft Production Board, nor its dubious achievements, in her correspondence.[6] Nor do the memoirs of Cather's friends Edith Lewis or Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant indicate whether Cather's fascination with World War I aviation extended into the area of engine development. Nevertheless, the story of the Liberty engine was frequently covered (and to some extent hyped) by a newspaper that we know Cather regularly read. And the thematic connections between Outland's achievement and Vincent and Hall's are hard to ignore: both engines drive a narrative of American ingenuity, modern mass production, profit, and controversy—all set against the background of the War to End All Wars. If I am right, then even the most seemingly fanciful of Cather's fictions—an implausibly revolutionary aircraft engine—has a complex basis in her material culture. Approaching Outland's invention through the prototype that I have offered adds further thematic resonance to The Professor's House, especially the novel's otherwise curious references to military aviation, and provides a vivid, albeit speculative, picture of Cather's creative process at work.[7]