From Cather Studies Volume 8

Picturing Their Ántonia(s)

Mikoláš Aleš and the Partnership of W. T. Benda and Willa Cather

When the narrator of Willa Cather’s 1918 introduction to My Ántonia claims that to “speak [Ántonia’s] name was to call up pictures of people and places”

and then agrees to partner with Jim Burden to “get a picture of her” by separately

recording their memories of Ántonia, Cather signals readers that the nature of picture

making will be an important element in her novel. The narrative is further layered

with set pieces and scenes that emphasize multiple perspectives and cooperation between

text and image. The handmade pastiche of pictures from a variety of sources that Jim

uses for Yulka’s Christmas scrapbook, the gilt-framed “crayon enlargement” of daughter

Martha that Ántonia orders at the photographer’s, and Ántonia’s box of photos that

provokes so much discussion during Jim’s visit are just a few instances where Cather

creates an interplay between image and narrative, and all of this is further complemented

by the addition of eight W. T. Benda illustrations she commissioned for the novel.

Suggesting that Cather and Benda’s work on the novel was a creative partnership, Jean

Schwind characterizes the illustrations as a “silent supplement” to the text and a

“needed corrective to the ‘romantic’ bias of Jim’s story” (59). The “linkage

Fig. 1. An example of the “Benda Woman” in a color illustration for Every Week magazine, 19 November 1917.An example of the “Benda Woman” in a color illustration for Every Week magazine, 19 November 1917."

of the visual and the verbal,” adds Janis Stout, demonstrates Cather’s understanding

of fine art where “isolation of individual details [lie] against an uncluttered middle

ground” and “the effect of visual acuity” becomes so important.

Fig. 1. An example of the “Benda Woman” in a color illustration for Every Week magazine, 19 November 1917.An example of the “Benda Woman” in a color illustration for Every Week magazine, 19 November 1917."

of the visual and the verbal,” adds Janis Stout, demonstrates Cather’s understanding

of fine art where “isolation of individual details [lie] against an uncluttered middle

ground” and “the effect of visual acuity” becomes so important.

Although various scholars have established that Cather’s knowledge of fine art was extensive and far-ranging, no one has considered whether the visual component of her novel about Bohemians can be traced back to any specific Bohemian art. Because of Cather’s numerous Bohemian friends, her love of their culture, and the Bohemian immigrant culture alive and well in New York at the time of her writing, it is not difficult to speculate that she would have both the inclination and the opportunity to seek out authentic Bohemian materials, especially when we consider the cultural and aesthetic similarities of Benda’s drawings with book illustrations done by the late-nineteenth-century Czech artist Mikoláš Aleš (1852–1913).

Among Czechs of the early twentieth century, Aleš’s work was as distinctive and ubiquitous as Norman Rockwell’s scenes of ordinary life were in midcentury America, and his bucolic depictions of peasant culture were beloved by Czechs of all classes in both the United States and Europe, where fellow Slav Wladyslaw Theodor Benda very likely saw Aleš’s work during his youth in present-day Poland. Examining Aleš’s work as part of a tradition that is essentially European can offer us insights into how we “read” the Benda illustrations and assess Cather’s goals for their intertextual function in her portrayal of Czech American culture within an agricultural West.

Although Mikoláš Aleš’s artistic sensibilities were shaped by his rural upbringing in a tiny village in southern Bohemia, he was destined for a broader national and international arena. When Aleš moved to Prague he came under the tutelage of Josef Manes, the father of modern Czech painting, widely known for his depiction of peasant women in native costume. Aleš’s early apprenticeship as a painter culminated in a commission in 1879 to be one of two artists to decorate the National Theater in Prague, “the most prominent and galvanizing Bohemian public project of the late 19th century” (Hume 57). Basing his work for the project on Czech folklore, Aleš named his cycle of paintings Vlast (homeland). However, when the project failed to bring him the respect of his peers in Prague, Aleš turned from oil painting to illustration. Working mostly in pencil, pen, charcoal, and watercolor, he quickly became a leader in both book and magazine illustration; and with thousands of illustrations to his credit, he is considered the founder of modern Czech book art. His popularity grew during the 1890s, and by time of his death in 1913, his depictions of Czech folklore and rural landscapes were broadly available in an extraordinary variety of magazines and books. His collection of illustrations titled Špalíček, first published in 1907, “is to a Czech childhood what Mother Goose is to a North American” (Sayers, “Quintessential” 158n, 154; Sayers, Coasts 113–14). Although a biography of Aleš appeared in 1912, it was his death the following year that triggered “countless laudatory and evocative obituaries [and] retrospective views on his work,” with one critic proclaiming him “monumental,” “a natural force and a cultural power,” and another “a genius of the people” (trans. and qtd. in Hume 58–59).

THE CASE FOR CATHER'S AWARENESS OF MIKOLÁŠ ALEŠ

Although Cather never mentions Aleš directly in the extant letters or in her published work, her personal interest in Czech culture from 1880 to 1917, her intimacy with Czech friends and associates, and her choices of residences offered multiple opportunities for her to encounter his work. Her years in Nebraska and Pittsburgh and her early years in New York coincided with waves of Bohemian immigrants coming into all three communities. We know, for instance, that Cather’s earliest associations with Czech immigrants began just after her arrival in Nebraska in 1883, and while this predates widespread dissemination of Aleš’s works in the States, by the time Cather left Nebraska in 1895, examples of his works had become available in calendars, cards, children’s primers, folk songs, and various ephemera and were sentimental favorites in Czech homes in America as well as Europe. For Czech émigrés, Aleš’s work often served as a spiritual connection to the essence of what they missed about the Czech lands. Between 1906 and 1918, Cather made regular, extended visits to Nebraska, typically calling on Czech-speaking friends. In Nebraska’s “Bohemian country” for five weeks during the 1912 harvest season, Cather was attentive to the cultural and scenic details she would use in “The Bohemian Girl,” the story she was completing at the time (Woodress 226). According to Antonette Turner, granddaughter of Annie Sadilek Pavelka, many Czech homes in the Red Cloud area displayed—even into the 1950s—“old country”–style illustrations in keeping with what Cather commissioned for My Ántonia[1] Czech American newspapers and periodicals, another possibility for seeing Aleš’s illustrations, were numerous in the early part of the century, and Cather references them in both My Ántonia, where Anton Cuzak brings home from Wilber a roll of illustrated Bohemian papers, and in “Neighbour Rosicky,” where four different passages make reference to Czech American newspapers. Unquestionably familiar to Cather’s friends in Nebraska was the illustrated bimonthly Hospodárˇ (“Husbandman” or “The Farmer”), which was then published in Omaha and claimed in 1920 a subscription of thirty thousand households.

Prior to this, Cather’s residence in Pittsburgh between 1895 and 1906 coincided with a surge of immigrants from the Czech lands and Slovakia attracted by jobs in the steel and coal industries, and by the 1920 census, Pennsylvania had the highest number of Czech-speaking immigrants in the nation (Čapek 12–19). Even after her subsequent move to New York, Cather visited Pittsburgh and remained a close friend of May Willard, the reference librarian at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library, which housed a dozen pre-1918 Czech publications, including Czech folk songs that Aleš was known to have illustrated. New York would have provided Cather with ample opportunities to observe the pageant of Czech immigrant culture. The city’s Czech population of more than forty thousand in the 1910 census, just after she relocated there, and of more than fifty thousand by 1918, lived and worked in neighborhoods within walking distance of Cather’s Bank Street apartment (Čapek 18; Cary, “Czecho-Slovak Exhibition”). Less than two miles east of her apartment was the oldest Czech neighborhood in the city, where she might have walked down “Czˇech Boulevard” (Avenue B), strolled through Tompkins Square Park (off Tenth Street), which was popular with Czech immigrants, or visited the Vesey Street neighborhood where Czechs like Rosicky worked in the factories. Uptown, less than five miles from Bank Street, the Yorkville neighborhood (east of Central Park, in the Seventies and Eighties) contained the Bohemian Quarter, where Czechs attended their own dances, theatricals, concerts, and public lectures at Národní Budova (National Hall), worshiped at both Catholic and Protestant Czech-language churches, maintained a Czech-language school, and joined innumerable lodges and union meeting halls. At the intellectual hub of the Bohemian Quarter was the Webster Free Library, considered New York’s “Czech Library” because of its long-standing efforts to accumulate Czech materials and serve as an exhibition hall and cultural center for Czechs (Davis 66). By the time Cather was working on My Ántonia, the library’s holdings included more than fifteen thousand volumes of books and various materials written in Czech, the largest collection outside of the Czech homeland. The library also subscribed to all three New York–based Czech newspapers and very likely others published in Cleveland, Cedar Rapids, and Chicago.

Prewar conflicts over the rule of the Czech lands, which led to their declaration of independence a month after the publication of My Ántonia, meant that U.S. newspapers were consistently covering issues and activities related to the culture and history of the Czech-speaking states, including several political protests in the United States led by philosopher Thomas Masaryk, who would later become the president of the nation of Czechoslovakia and, after he read My Ántonia, Willa Cather’s correspondent. Additionally, the New York Times regularly discussed Czech art history in the “Art at Home and Abroad” column written by Elisabeth Luther Cary. As early as December 1913, the Times highlighted a local showing of Bohemian graphic art (“Interesting Collection”), and again in December 1917—the same time Cather was negotiating with Benda and her publisher about the makeup of the illustrations—Cary makes note of an exhibit of Czecho-Slovak folk art at the Metropolitan Museum, which also hosted a well-attended lecture and provided a flyer on Bohemian history and immigration (“Czecho-Slovak Exhibition”). Just a week after the publication of My Ántonia, Cary specifically identifies Mikoláš Aleš as a leader in Czech graphic art (“Czechoslovak Spirit”), and six months later she praises his Prague National Theater murals as “one of the most splendid expressions of Bohemian art of the nineteenth century” and Aleš himself as an “incomparable illustrator of Czech folk songs . . . imbued . . . with a strong national pride” (“Proud Artistic Past”). Cather, therefore, had numerous opportunities to see his work in any number of mediums.

HIRING THE RIGHT MAN FOR THE JOB

According to Schwind, Cather not only sought out W. T. Benda as illustrator for My Ántonia but also functioned as the novel’s art director. However, Schwind’s characterization of Cather as “autocratic” in these matters (53) does not fully take into account the battle Cather had to wage, especially against R. L. Scaife, the production editor Greenslet had put in charge of the novel’s publication.[2] In a series of impassioned letters, Cather argued with Scaife about the number and style of the illustrations, her choice of Benda as illustrator, a fair amount to pay the artist, and the sizing and placement of illustrations in the text. She held fast when Scaife expressed reluctance to use Benda, and for a time she ignored the condescending tone of his characterizations of Benda’s work as “little pictures.” During Cather’s years as managing editor of McClure’s, Benda had contributed more than a dozen illustrations to the magazine—an association that would continue after her departure and earn him the nickname of McClure’s “war-horse,” as art historian Mark Pohlad writes, “because he was counted on to create high-level work quickly and competently” (“Masks” 12), a talent that led to regular cover and story commissions for numerous top magazines, including Colliers, Century, Scribner’s, Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Cosmopolitan.

Having illustrated some of her own work earlier in her career, Cather attempted her own drawings for the novel and thus had a clear notion of what she wanted. If Benda could not achieve the feeling she was after, Cather wrote Scaife, no one could (18 October 1917). She refused when Scaife suggested a single-color frontispiece that could be used for advertising rather than the series of pen-and-ink drawings she envisioned. While she acknowledged that a single-wash drawing, a medium in which Benda had become proficient, would have been easier for the artist, what she and Benda had decided upon were twelve illustrations in the style he had used in drawings for Jacob Riis’s 1909 book The Old Town (24 November and 1 December 1917). However, over the course of the next few months, it became increasingly clear that Scaife failed to value Benda’s contribution or understand Cather’s vision of the book’s visual design, especially when he wrote Cather, “I had pictured an attractive little book with illustrations that would appeal to the dilettante, rather than to the average novel reader” (3 December 1917). In a letter of complaint to Greenslet dated 24 November 1917—the longest regarding the illustrations—Cather expressed her displeasure about what she saw as Scaife’s interference and insisted that unless the illustrations were a meaningful supplement to the text, instead of a mere decoration, she wanted no illustrations at all (see also 13 March and 18 October 1917). At one point, Cather placed the blame for production difficulties and delays squarely on Scaife’s shoulders and suggested that Scaife withdraw from the project or, if they could not come to some agreement, that Greenslet pay for Benda’s work on the three completed drawings, with the understanding that none would be used.

Cather stood by her belief that Benda was the right man for the job, even when Scaife urged her to consider, among others, two illustrators whom he claimed knew the West (6 April 1917). One was Joseph Clement Coll, a self-taught illustrator of stories by Arthur Conan Doyle and Charles Dickens who helped define the look of adventure illustration but showed little understanding of the West; the other was Charles Nicholas Sarka, an illustrator working for second-tier magazines such as American Magazine, Munsey’s, Success, and Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (for which he was doing a series of Uncle Sam illustrations). If Cather ever considered other artists or artistic styles, there were at least two candidates not mentioned by Scaife who represented what most Americans would have then associated with Czech art and design. Moravian-born Alphonse Mucha, who had taught and exhibited in New York between 1904 and 1910 and was known for poster depictions of Sarah Bernhardt, was the most recognizable Czech artist in New York. His distinctive “le style Mucha” offered goddess-like depictions of languid, eroticized women framed by elaborate botanical designs, and had Cather instructed her illustrator to work in that style, the result would have been a provocative, intensely sexualized Ántonia in a verdant landscape—all wrong for Cather’s book. Cather could have considered engraver Rudolph Ruzicka, a Czech immigrant and rising star in New York art circles known for his cityscapes. In 1915, 1916, and later in 1935, Cather sent out Christmas cards featuring Ruzicka’s urban scenes, and later she agreed to using his designs for both the dust jacket for Lucy Gayheart (1935) and the cover art for Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940)—although in both cases the art was decorative rather than scenic.[3]

After a series of compromises about fees and the number of illustrations, Cather prevailed, and the resulting pairing of text and image so pleased her that she protested both when Greenslet pulled the drawings in a later edition and when he proposed a “deluxe” edition in which illustrations by Grant Wood would replace Benda’s. Although Greenslet may have assumed Wood’s work could be a selling point, Cather was clear: Wood’s vision of the West was not right for the job, and her Ántonia “must be saved from flashy color illustrations in general and from Wood’s illustrations in particular” (29 December 1937; paraphrased in Schwind 52). Cather’s 24 November 1917 letter to Greenslet, a manifesto concerning Benda’s role in the novel’s visual composition, confirms Stout’s assertion that “visual design was a part of her creative act of authorship” (133). Seeing her work with Benda as a joint venture, Cather describes a fully integrated visual component that enhances the novel’s narrative and composition, and maintains that Benda’s drawings exceeded her expectations in their ability to capture the tenor of the text. In addition to citing Benda’s sympathy for and understanding of western landscapes, he had, she wrote, a special knowledge of Bohemian culture and a willingness to collect background material for the job, although Cather does not specify what background materials he had researched.

ARRIVING AT BENDA'S ÁNTONIA

Although Polish-born and city-bred, Benda did indeed understand Bohemian and western American culture. Raised in an artistic family interested in music and theater, Benda studied art in Kraków and then Vienna, a background, writes art historian Mark Pohlad, that gave him amply opportunity to “admire age-old Slavic artworks” and study methods of the Slavic masters (“Masks” 5). Pohlad agrees that Benda’s education almost certainly included some of Aleš’s work, because at the end of the nineteenth century, Poles and Czechs were both part of the Austro-Hungarian empire and had significant geographic, linguistic, historical, and political connections. The result was a pan-Slavic National Revival movement, in which intellectuals and artists advocated cultural unity and opposition to Habsburg rule (e-mail correspondence with Pohlad). While pan-Slavism was short-lived as a movement, the questions it raised about national sovereignty and ethnic identity—as seen in the work of Aleš— dominated all aspects of Slavic art from 1848 to 1918. Such political turmoil, however, also led to increased emigration, and in 1898 the Benda family left Europe for California to join Benda’s aunt, the famous actress Helena Modjeska (who appears in My Mortal Enemy[1926]). Working on Modjeska’s ranch alongside seasoned cowboys, the artist gained experiences that would inform his illustrations for a 1910 ranching memoir. Poised between work in the American West and allegiance to Slavic cultural history, he was clearly a good choice.

Recognizing the singularity of his illustrations in their depiction of ethnicity, however, further illuminates why Cather had so vehemently championed Benda. Talented in portraying ethnic women, he became known for the “Benda Woman,” who was “confidently handsome,” “languid and self-assured,” “exotic,” “more mysterious, more explicitly foreign-looking” than other American types (fig. 1). Having once said that he favored ethnic subjects, Benda “flattered and glamorized the new female populations” and “helped them feel like they were being represented in the mainstream press,” especially in his 1913Century magazine feature “New-Made Americans: A Few Types of Foreign Women Sketched, in New York, from the Life,” in which he “demonstrated . . . [a] gift for capturing national characteristics and costume” (Pohlad, “Masks” 15). The “Benda Woman” was created during an era when periodicals were preoccupied with defining the quintessential “American Girl,” consistently portrayed as a middle-class ingenue without any distinctive ethnic identity—the antithesis of Cather’s immigrant farm woman. Identified in possessive terms as the “Gibson Girl” (Charles Dana Gibson), the “Christy Girl” (Howard Chandler Christy), the “Flagg Girl” (James Montgomery Flagg), the “Fisher Girl” (Harrison Fisher), and the “Underwood Girl” (Clarence Underwood), these iconic portrayals were meant to codify a sanitized and idealized version of American femininity. Underwood, who had disappointed Cather with his portrayal of her Swedish heroine Alexandra in the frontispiece of O Pioneers! (1913), typified what Cather did not want when he asserted in his 1912 book American Types that he portrayed a womanly beauty “unspoiled by the artificial restraints of ceremonious Europe” (qtd. in Stouck). Is it any wonder, then, that Cather sought an artist willing to portray her Ántonia with cultural understanding and sensitivity?[4]

While Benda’s willingness to portray immigrant women accurately and sympathetically must have played a role in Cather’s decision, what is most telling about his other work from that period is that it is quite different from the illustrations he executed for My Ántonia. For instance, most of Benda’s scenes in Riis’s The Old Town, the book Cather cited in her 1917 letters to Greenslet, are set in cities rather than the countryside and more often than not rendered in close-up, in keeping with his studies of ethnicity. By contrast, the faces illustrated for Cather’s novel are merely suggested with simple lines, or the characters are poised with their backs to us, so that their faces (Benda’s absolute stock-in-trade) are hidden. In two of the four Benda illustrations of Ántonia, she is almost entirely in silhouette (at the train station and while plowing), and in the third, the sunset picture, she is depicted completely in silhouette and has her back turned to the viewer; even in the last image, of a pregnant Ántonia driving cattle in a blizzard, her face is barely visible between a hat and a turned-up collar. Of the novel’s eight illustrations, only the depiction of a barefoot Lena Lingard knitting in the fields shows a face in much detail, and even in this, Lena’s look of concentration barely suggests the intensity of a typical “Benda Woman.” While the illustrations for My Ántonia fit Benda’s attention to immigrant subject matter, Pohlad notes that they are “singular in Benda’s career . . . . very ‘old country’” (e-mail correspondence) and “totally unlike the suave charcoal and color magazine cover” work he typically did (“Masks” 25). In insisting that Benda be the illustrator of My Ántonia, Cather found an illustrator who could draw upon a style of someone like Aleš, a style in which the rural landscape is as important as the characters who move through it.

READING ALEŠ’S STYLE AND THEMES

Aleš’s illustrations demonstrate what Derek Sayers calls a “sturdy virility of line,”

and his “simplification, even an infantilization” gives the work “its enduring charm”;

“accessible and unpretentious,” his work embodies “an authentically, irreducibly Czech art,” a “quintessential Czechness—Czech has a word for it, cˇeskost—that is rooted in the people and the land whence they sprang” (“Quintessential” 153,

161, 154–55, 141) (fig. 2). With an emphasis on simplicity, authenticity, and regional

loyalty that should echo with Cather scholars, Aleš was deemed unapologetically sentimental

and backward-looking (outdated by some), but because his art expressed the deeply

valued qualities of Czech identity, he could not be ignored. According to art historian

V. V. Stech, he “became a patriot outside of time, a representative of times which

are irrevocably gone. . . . We no longer feel the backwardness in Aleš’s form, . .

. because we understand that the peculiar freshness of this painter is the result

of pure sincerity, the fruit of an intensely lived youth, of his experience, of his

ideals, to which he adhered even if they were romantic and uncontemporary” (qtd. in

Sayers, Coasts 189). Citing the profound national pride that Czechs felt in this art, critic J.

Smetanova claims that Aleš’s art depicts “the nuances of our nature and our perception

of the world” in drawings that are “as timeless as the folksong.” Aleš could perceive

“the instants of truth” in the “beauty of the land and the joys and sorrows of

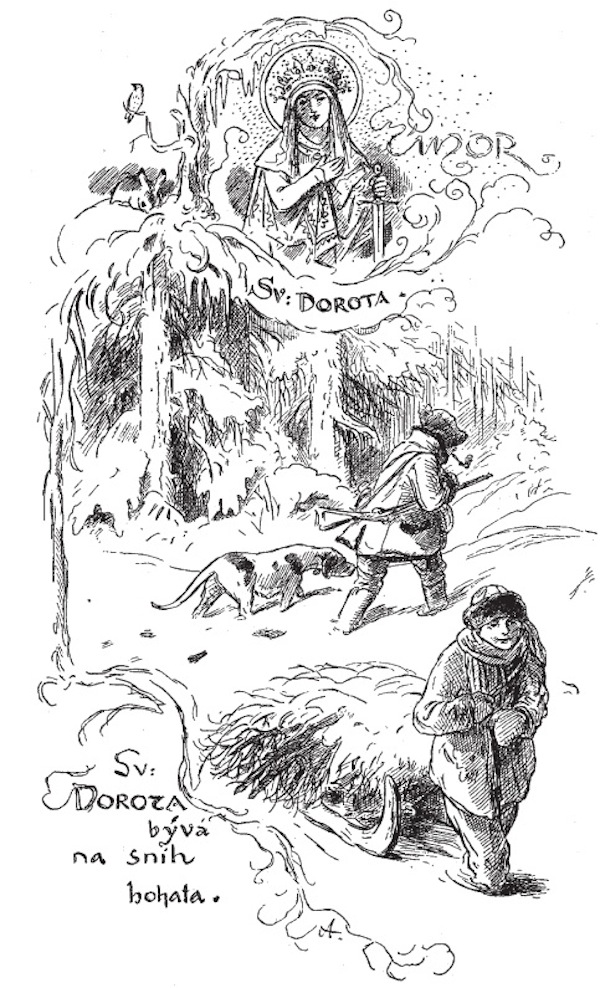

Fig. 2. A man and dog go hunting while another man pulls a hay-filled sleigh. Aleš

ink-and-pen calendar illustration for Saint Dorota Day in February.A man and dog go hunting while another man pulls a hay-filled sleigh. Aleš ink-and-pen

calendar illustration for Saint Dorota Day in February.

those for whom it is home” (53). Such high praise is understandable when we consider

that Aleš’s work was popularized during a period of national cultural revival and

responded to a need for an ethnic patriotism, solidifying Czech resolve to preserve

sovereignty and identity within the Viennese-centered culture of Habsburg rule. Following

the 1848 Cultural Revolution, artists turned away from Vienna as exemplifying the

best in style, form, and subject matter and revived an art focused on Bohemian folklife

and countryside (Mackova 26). Aleš accepted his role in this national movement, explaining

that if “it isn’t of any worth as art then there is still the national bit which I

wished to preserve. Art isn’t all that important to me—it is only a means of expressing

the national entity. . . . Through my work I want to awaken the people and have them

regain of old, unyieldingness and independence” (trans. and qtd. in Smetanova 53).

Fig. 2. A man and dog go hunting while another man pulls a hay-filled sleigh. Aleš

ink-and-pen calendar illustration for Saint Dorota Day in February.A man and dog go hunting while another man pulls a hay-filled sleigh. Aleš ink-and-pen

calendar illustration for Saint Dorota Day in February.

those for whom it is home” (53). Such high praise is understandable when we consider

that Aleš’s work was popularized during a period of national cultural revival and

responded to a need for an ethnic patriotism, solidifying Czech resolve to preserve

sovereignty and identity within the Viennese-centered culture of Habsburg rule. Following

the 1848 Cultural Revolution, artists turned away from Vienna as exemplifying the

best in style, form, and subject matter and revived an art focused on Bohemian folklife

and countryside (Mackova 26). Aleš accepted his role in this national movement, explaining

that if “it isn’t of any worth as art then there is still the national bit which I

wished to preserve. Art isn’t all that important to me—it is only a means of expressing

the national entity. . . . Through my work I want to awaken the people and have them

regain of old, unyieldingness and independence” (trans. and qtd. in Smetanova 53).

Aleš was as independent in his ideas about art as he was in his subject matter, and in the 1920s his works appealed to avantgarde artists throughout central Europe who saw illustration as a valid form of fine arts, not as provisional preparation for a more finished painting (Hume 48). He was lauded for executing the consummate interdependence of text and image, and his images are visually engaged with the text or seem literally to embrace the text, weaving words within the scenes or positioning the text as a pivot point between related images. Traditional designs using organic elements such as vines and branches, flowers, rosemary, and thistles sometimes frame and even “grow” into the texts. Aleš’s “text-image intertwining” (Hume’s term) has a narrative quality that begs the reader to move from image to text and back again, accumulating meaning and understanding with each move. Often the first, ornate letter of the text encapsulates vignettes that are thematically related to the text but may subtly undercut the narrative of the larger picture. For instance, in one illustration a young woman leans out her window to kiss her soldier lover good-bye, and nestled in the first letter is a heart, which is often found in traditional Bohemian designs, although here it is ominously stabbed with a knife (Aleš, Špalíček 124). Another drawing depicts a sweet old woman who makes a living by harvesting and drying herbs, but within the verse’s opening letter T, which is formed by crossed bones, is the vignette of a graveyard—the future she cannot help but contemplate (Aleš, Špalíček 183). Text and image, therefore, partner in Aleš’s work, just as in Cather’s novel the “stark black-and-white drawings by Benda . . . provide a realistic balance for Jim Burden’s romantic memoir” (Woodress 287–88).

PARALLELS EVIDENT IN AN ALEŠ/BENDA/CATHER PARTNERSHIP

While the biographical possibilities for Cather encountering Aleš’s work at any number of points in her life are worth noting, the cultural and aesthetic similarities between Aleš’s work and the Benda illustrations in My Ántonia offer the most interesting case for an Aleš-Cather connection. As Benda does in My Ántonia, Aleš illustrates stories of women caring for sapling trees, men setting out for woodlands with guns slung over their shoulders, homeless old women giving apples to children or gathering herbs to sell, tramps wandering through rural landscapes, women harvesting grain or driving stock in the fields, old men facing a long winter and their own mortality, little girls cupping ladybugs in their hands, frantic sleigh rides through bitter cold landscapes, friends toasting each other under an arbor, and daughters mourning at grave markers set on the edge of farm fields (fig. 3). The extent to which the work of Aleš parallels both Cather’s subjects and Benda’s illustrations illuminates issues of both ethnic identity and visual culture in the novel.

Like Cather, Aleš paid special attention to the land itself, imbuing it with religious

imagery that suggested it as the source of the people’s fortitude and spiritual superiority.

When Aleš illustrated Alois Jirásek’s Staré Poveˇsti (Old Czech Legends), another product of the Czech National Revival, his images confirmed

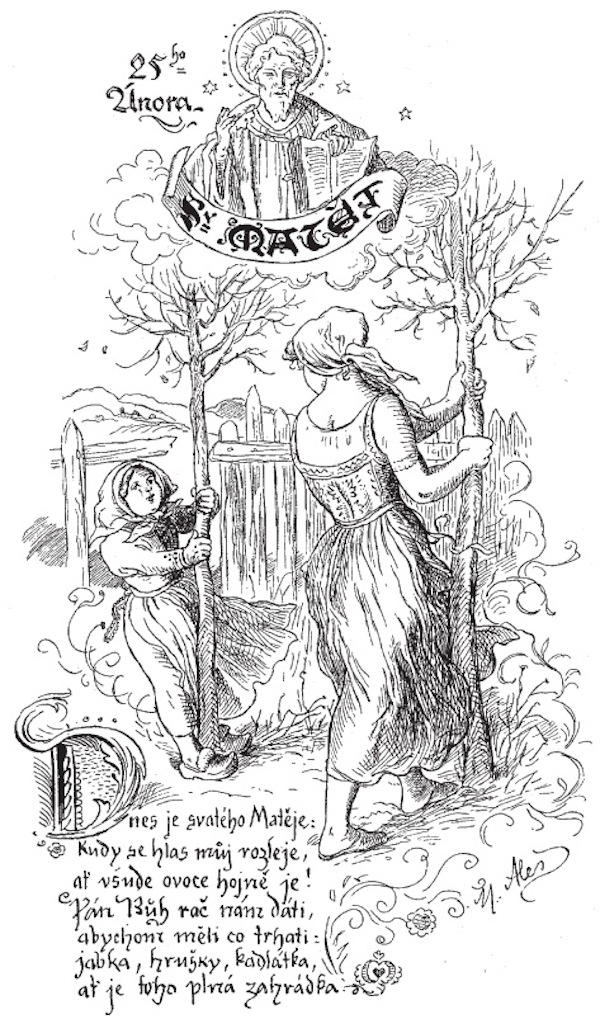

Fig. 3. A woman and child posed with sapling trees. The poem is a prayer asking God

to give plenty of apples, pears, and plums to fill the garden. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar

illustration for Saint Matthew Day, 25 February.A woman and child posed with sapling trees. The poem is a prayer asking God to give

plenty of apples, pears, and plums to fill the garden. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar

illustration for Saint Matthew Day, 25 February.

Jirasek’s plea in the introduction to understand Czech history and believe in the

goodness of the earth:

Reflect on the first years of our country, what was its face before our brood set

foot here. . . . Almost all the soil rested, not being touched by plough. . . . Human

track was rare here. . . . The depth of the earth was still locked and nobody attempted

to open it to receive treasures of ores and precious metals. Strength and riches were

everywhere, the land was ready to give its bounty to industrious people to enjoy.

And they came. Aggrandizing it with their hard work and making it sacred with their

sweat and blood spilled in many battles, defending it and their language. (Mikoláš

Aleš Gallery)

Jirasek’s description of a land “before our brood set foot here” resonates with Cather’s

assertion in My Ántonia that there is “nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which

countries are made” (7). Jirasek’s assurance that “the land was ready to give its

bounty to industrious people” is as clearly played out on the Cuzak farm as in the

agrarian scenes of Aleš’s illustrations.

Fig. 3. A woman and child posed with sapling trees. The poem is a prayer asking God

to give plenty of apples, pears, and plums to fill the garden. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar

illustration for Saint Matthew Day, 25 February.A woman and child posed with sapling trees. The poem is a prayer asking God to give

plenty of apples, pears, and plums to fill the garden. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar

illustration for Saint Matthew Day, 25 February.

Jirasek’s plea in the introduction to understand Czech history and believe in the

goodness of the earth:

Reflect on the first years of our country, what was its face before our brood set

foot here. . . . Almost all the soil rested, not being touched by plough. . . . Human

track was rare here. . . . The depth of the earth was still locked and nobody attempted

to open it to receive treasures of ores and precious metals. Strength and riches were

everywhere, the land was ready to give its bounty to industrious people to enjoy.

And they came. Aggrandizing it with their hard work and making it sacred with their

sweat and blood spilled in many battles, defending it and their language. (Mikoláš

Aleš Gallery)

Jirasek’s description of a land “before our brood set foot here” resonates with Cather’s

assertion in My Ántonia that there is “nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which

countries are made” (7). Jirasek’s assurance that “the land was ready to give its

bounty to industrious people” is as clearly played out on the Cuzak farm as in the

agrarian scenes of Aleš’s illustrations.

Women in the fields are a staple of Aleš’s art, and his portrayals offer self-assured

women with open hands and bare feet that practically root them to the ground, or women

confessing their most private sorrows to an amenable landscape, as if the fields themselves

were a confidante; it is as if Aleš, not Cather’s Jim Burden, were depicting an Ántonia

who “kept stopping to tell me about one tree and another. ‘I love them as if they

were people,’ she said, rubbing her hand over the bark” (340). But Aleš’s “Ántonias”

are also the true daughters of Libuše, the courageous woman warrior from Czech mythology

who married Prˇemysl, the Ploughman, and directed her people to establish the city

of Prague. At the top of an August (“Srpen”) calendar page, for instance, Aleš depicts

a war scene that includes a passage from The Chronicle of Dalimil (Dalimilova kronika), a fourteenth-century

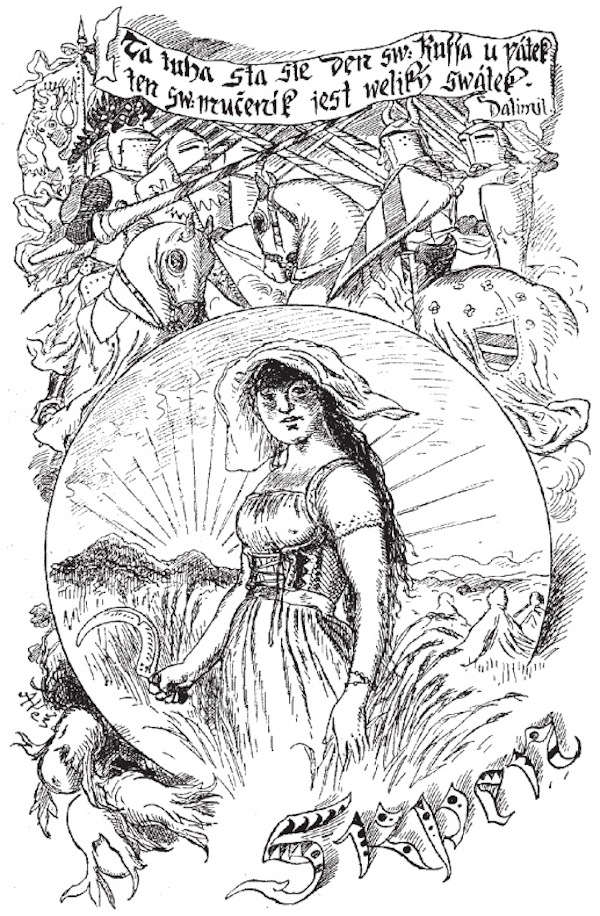

Fig. 4. A woman with scythe below a scene from the “The Girls’ War,” as described

by fourteenth-century historian Dalimil. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar illustration for

August.A woman with scythe below a scene from the “The Girls’ War,” as described by fourteenth-century

historian Dalimil. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar illustration for August.

history about Libuše and “The Girl’s War.” Under the quote and war vignette, a Czech

farm woman grips a reaping hook as if she holds a weapon with which she is protecting

her own fields (fig. 4). Aleš thus associates Libuše’s leadership and her founding

of the Czech nation with the courage of an ordinary farm girl. Unlike Mucha’s provocatively

posed women, this is clearly a working woman, but sensuality and labor are not mutually exclusive here. With curving hips

and full breasts suggesting the fecundity of both the land and her people, her body

is the source of a power and connection to a place. Her erect nipples are revealed

against her taut bodice, much as in Benda’s depiction of Lena in the fields, a sensual

portrayal that had the full approval of Cather, who wrote to Greenslet that Benda’s

Lena was almost splitting her clothes (7 March 1918). Critics have discussed both

Cather’s and Benda’s characterization of Lena in ways that particularly echo the sensuality

of Aleš’s farm women: Jean Schwind writes that Benda’s Lena “fairly bursts from her

scanty dress; the carefully delineated nipple pressing against her bodice is the most

conspicuous” (66), and Blanche Gelfant notes how in Cather “Lena’s voluptuous aspects—her

luminous glow of sexual arousal, her flesh bared by a short skirt, her soft sighs

and kisses—are displayed against shocks and stubbles, a barren field where the reaping-hook

has done its work” (65).

Fig. 4. A woman with scythe below a scene from the “The Girls’ War,” as described

by fourteenth-century historian Dalimil. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar illustration for

August.A woman with scythe below a scene from the “The Girls’ War,” as described by fourteenth-century

historian Dalimil. Aleš ink-and-pen calendar illustration for August.

history about Libuše and “The Girl’s War.” Under the quote and war vignette, a Czech

farm woman grips a reaping hook as if she holds a weapon with which she is protecting

her own fields (fig. 4). Aleš thus associates Libuše’s leadership and her founding

of the Czech nation with the courage of an ordinary farm girl. Unlike Mucha’s provocatively

posed women, this is clearly a working woman, but sensuality and labor are not mutually exclusive here. With curving hips

and full breasts suggesting the fecundity of both the land and her people, her body

is the source of a power and connection to a place. Her erect nipples are revealed

against her taut bodice, much as in Benda’s depiction of Lena in the fields, a sensual

portrayal that had the full approval of Cather, who wrote to Greenslet that Benda’s

Lena was almost splitting her clothes (7 March 1918). Critics have discussed both

Cather’s and Benda’s characterization of Lena in ways that particularly echo the sensuality

of Aleš’s farm women: Jean Schwind writes that Benda’s Lena “fairly bursts from her

scanty dress; the carefully delineated nipple pressing against her bodice is the most

conspicuous” (66), and Blanche Gelfant notes how in Cather “Lena’s voluptuous aspects—her

luminous glow of sexual arousal, her flesh bared by a short skirt, her soft sighs

and kisses—are displayed against shocks and stubbles, a barren field where the reaping-hook

has done its work” (65).

Although Aleš’s illustrations typically express joy in cultivation, they also offer

an unflinchingly harsh view of life; even in illustrations for children’s primers,

grim realities coexist with epic strength. Skeletal reapers and serene saints are

set side by side, and the lurking specters of death and sorrow make Aleš’s work analogous

to Cather’s novel, which portrays no less than three suicides, three murders, rape,

abandonment, near starvation, betrayal, desperation, greed, selfishness, and cultural

and personal annihilation (fig. 5). In Aleš, when characters struggle emotionally

and physically, their sorrow takes place within an orderly landscape, just as Ántonia’s

horrific story of the tramp’s suicide in a threshing machine is told within the comfortable

setting of the Harling kitchen, and her story of the homeless Old Hata is

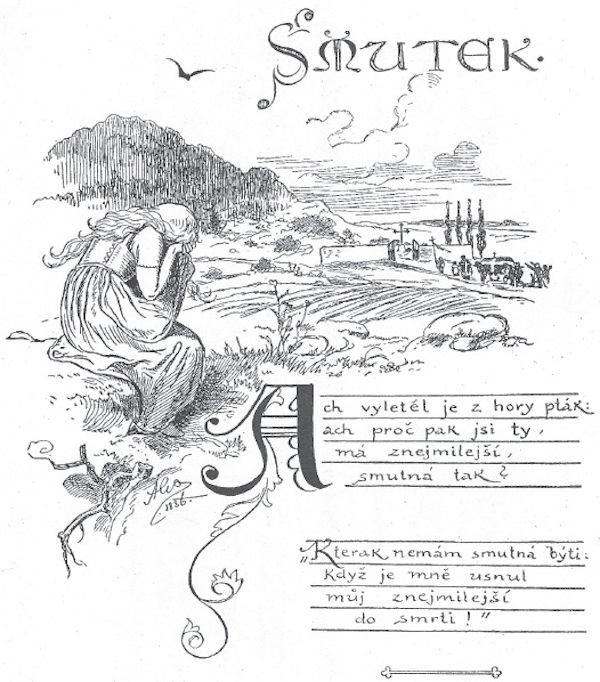

Fig. 5. A woman crying for her lover as his funeral procession marches to a cemetery

in the distance. The drawing’s title, “Smutek,” means grief or mourning. Aleš ink-and-pen

illustration (1886) of a Bohemian song.A woman crying for her lover as his funeral procession marches to a cemetery in the

distance. The drawing’s title, “Smutek,” means grief or mourning. Aleš ink-and-pen

illustration (1886) of a Bohemian song.associated with fondly remembered music and a pleasant, grassy bank. Czech writer

Karel Čapek suggests that Aleš’s genius lies in his ability to be expansive in his

vision and to encompass precisely these kinds of contradictions: “Next to monumental

frescoes[,] little pictures for a children’s reader; alongside almanacs, heroic myths.

Father Aleš has everything altogether in one bundle: national idyll and national epic,

the beetle in the grass and the knights in combat, nature and history, children and

the king, animals and elements, present and prehistory, . . . the presence of everything

that home means to us” (qtd. in Sayers, Coasts 189–90). More than once Aleš illustrated the Czech national anthem, titled “Kde je

Domov?” (“Where Is My Home?”), which considers the irony of Czechs feeling exiled

in their home country during Habsburg rule. But Aleš urged renewed faith in the countryside

as the source of identity.[5] Cather likewise indicated for ordinary farming people of the American Midwest the

defining value of an emotional as well as practical relationship to the land. While

Czechs would have recognized in Aleš’s illustrations a desire for sovereignty and

self-determination and a call for political and cultural loyalty to a place, American

readers of My Ántonia recognized a call for respecting regionalism and celebrating the immigrants’ desire

to make a strange land into a home without forsaking loyalty to homeland.

Fig. 5. A woman crying for her lover as his funeral procession marches to a cemetery

in the distance. The drawing’s title, “Smutek,” means grief or mourning. Aleš ink-and-pen

illustration (1886) of a Bohemian song.A woman crying for her lover as his funeral procession marches to a cemetery in the

distance. The drawing’s title, “Smutek,” means grief or mourning. Aleš ink-and-pen

illustration (1886) of a Bohemian song.associated with fondly remembered music and a pleasant, grassy bank. Czech writer

Karel Čapek suggests that Aleš’s genius lies in his ability to be expansive in his

vision and to encompass precisely these kinds of contradictions: “Next to monumental

frescoes[,] little pictures for a children’s reader; alongside almanacs, heroic myths.

Father Aleš has everything altogether in one bundle: national idyll and national epic,

the beetle in the grass and the knights in combat, nature and history, children and

the king, animals and elements, present and prehistory, . . . the presence of everything

that home means to us” (qtd. in Sayers, Coasts 189–90). More than once Aleš illustrated the Czech national anthem, titled “Kde je

Domov?” (“Where Is My Home?”), which considers the irony of Czechs feeling exiled

in their home country during Habsburg rule. But Aleš urged renewed faith in the countryside

as the source of identity.[5] Cather likewise indicated for ordinary farming people of the American Midwest the

defining value of an emotional as well as practical relationship to the land. While

Czechs would have recognized in Aleš’s illustrations a desire for sovereignty and

self-determination and a call for political and cultural loyalty to a place, American

readers of My Ántonia recognized a call for respecting regionalism and celebrating the immigrants’ desire

to make a strange land into a home without forsaking loyalty to homeland.

Lastly, I wish to note how Aleš’s marriage of text and image has echoes in the complex visual culture of My Ántonia. Diverse visual aspects concern Cather in both the book’s composition and the narrative itself. The clues she offers about how to interpret the picture book Jim creates for Yulka lie in the juxtaposing of circus scenes printed on calico, lithographs of paintings from magazines, advertising and Sunday-school cards brought from Virginia, and a frontispiece of “Napoleon Announcing the Divorce to Josephine.” If Jim intends any specific message with this collection of contradictions, he never expresses it. On the other hand, the desire to portray, shape, and frame visual perception in a meaningful way dominates the “Cuzak’s Boys” section. After Jim witnesses Ántonia’s children interpret photos that document his past, his impulse, as they move outside to the fruit cave, is to create his own mental photos: That moment, when they all came tumbling out of the cave into the light, was a sight any man might have come far to see. Ántonia had always been one to leave images in the mind that did not fade—that grew stronger with time. In my memory there was a succession of such pictures, fixed there like the old woodcuts of one’s first primer: Ántonia kicking her bare legs against the sides of my pony when we came home in triumph with our snake; Ántonia in her black shawl and fur cap, as she stood by her father’s grave in the snowstorm; Ántonia coming in with her work-team along the evening sky-line. She lent herself to immemorial human attitudes which we recognize by instinct as universal and true. (341–42)

Like Aleš’s, Jim’s “pictures” here are unposed moments from an ongoing life, word pictures, if you will, that engage in a dialogue with the Benda illustrations. Jim’s memory of seeing Ántonia behind the team resonates with Benda’s illustration of her behind the plow, but the interplay also suggests thematic parallels—for instance, Jim’s memory of Ántonia in shawl and cap shivering at her father’s grave recalls not only that scene but Benda’s winter scene set before Martha’s birth, in which a hat and ulster do not adequately protect Ántonia from the cold or her emotional pain. The interplay of text and image makes both even more evocative. Aleš proved that illustration was not merely a “silent supplement” that decorated a text, the very point that Cather had fought about with Scaife. Illustration bears equally the weight of creating meaning in Aleš. With a primer such as the kind Jim cites and Aleš illustrated, children rely on image to confirm their translation of letters into words and symbols into sense. If Aleš’s work teaches us anything, it is about the kind of intertextuality in which, as one of Aleš’s admirers explains, “It is not possible to extract the drawing from the script on these pages, so mutually do they fulfill each other” (trans. by and qtd. in Hume 54).