From Cather Studies Volume 9

Thea at the Art Institute

In an important scene in The Song of the Lark, Thea Kronborg finally goes to the Art Institute of Chicago—something she has been urged to do for months. Cather not only describes Thea’s joy at her discovery of this museum but also tells readers which sculptures and paintings Thea finds particularly interesting. Although scholars have noted the importance of this episode in the novel and identified the paintings that draw Thea’s attention (Duryea), the young singer’s experience in the Art Institute merits closer analysis—an analysis not so much of the artworks themselves as of Thea’s response to them. Through this short episode (it covers less than two pages in the novel), Cather conveys a good deal about this provincial girl who is in the early, stillinarticulate stages of turning herself into a sophisticated artist. Cather implies a progression in Thea’s gradually growing understanding of beauty, with her experience in the Art Institute building on her childhood experiences in Colorado and laying the groundwork for her later insights into art in Panther Canyon. Further, reflection on the painting central to Thea’s experience in the Art Institute, Jules Breton’s The Song of the Lark, suggests that that artwork may have influenced Cather’s technique in the novel’s concluding pages, and, perhaps, her later shift from the “full-blooded method” of The Song of the Lark (Cather, “My First Novels” 96) to a sparer, more modernist style.

When Thea arrives in Chicago to study piano, she is unaware that she needs an education not only in music but in the arts in general. As her teacher Andor Harsanyi observes, she is strangely “incurious” about the opportunities Chicago offers (463). Her landlady, Mrs. Lorch, and her landlady’s daughter, Mrs. Anderson, different as they are from Harsanyi, also remark that Thea has “so little initiative about ‘visiting points of interest’” (464). When Mrs. Lorch asks Thea over dinner one evening if she has been to the Art Institute, Thea asks her if that is “the place with the big lions out in front? I saw it when I went to Montgomery Ward’s. Yes, I thought the lions were beautiful” (464). For the still-provincial Thea, the Art Institute is initially notable only for its lions and its location—on the route to the “big mail-order store” which, with Chicago’s meat-processing plants (464), are the two “points of interest” that most intrigue the Colorado native. As part of her effort to be sociable “without committing herself to anything” (464), Thea “reassure[s]” Mrs. Lorch and Mrs. Anderson that she will go to the Art Institute “some day” (465).

When Thea does finally take herself there one “bleak day in February” (465), the museum is a revelation to her; she leaves it chastising herself for not having gone sooner and promising herself that she will return regularly. This is a pledge she keeps; Cather implies that Thea develops a regular pattern at the Institute, always visiting certain artworks when she is there. With one exception, Cather is quite specific about the works to which Thea turns her attention. But despite her later remark that in this novel she “told everything about everybody” (“My First Novels” 96), Cather leaves it largely to the reader to discern why these particular works are so important to Thea. In doing so Cather puts her readers in Thea’s position: if Thea is drawn to these works repeatedly by some quality she cannot quite define, so we, too, are drawn back to this passage to wonder exactly how each work contributes to Thea’s growth as an artist.

Thea always visits the casts first, finding them both “more simple and more perplexing” than the paintings; they also seem to her “more important, harder to overlook” (465). Cather mentions four casts (i.e., copies of famous sculptures, widely found in American museums of that era), three of which Thea examines only briefly. She almost dismisses The Dying Gladiator (or Dying Gaul) because she is already familiar with it from Byron’s “Childe Harold,” a poem she has pored over while ill in bed; for her, the cast is “strongly associated with Dr. Archie and childish illnesses” (466).[1] Although her reaction to the Venus di Milo is not as strong as Paul’s in “Paul’s Case” (he makes “an evil gesture at the Venus of Milo as he passed her on the stairway” [470]), Thea is baffled by her: “she could not see why people thought her so beautiful” (464). Similarly, she does “not think the Apollo Belvedere ‘at all handsome’” (466).

The very familiarity of these casts leads Thea to notice them but also to dismiss them. As works apparently already known in Moonstone, they are examples of merely conventional beauty—something against which Thea has rebelled since her first intimation that her own abilities were superior to those of the popular Lily Fisher. Indeed, Thea also rejects Moonstone’s admiration of Lily Fisher’s good looks. Cather both conveys Thea’s attitude and subtly endorses it when she describes Lily as looking “exactly like the beautiful children on soap calendars” (348). From Thea’s point of view, perhaps the young Venus di Milo or Apollo Belvedere would have been suitable models for advertisements geared to a broad, bland public.

In contrast, a fourth cast—the only one Cather does not identify by name—fascinates Thea: “Better than anything else she liked a great equestrian statue of an evil, cruel-looking general with an unpronounceable name. She used to walk round and round this terrible man and his terrible horse, frowning at him, brooding upon him, as if she had to make some momentous decision about him” (466). This is probably Andrea del Verrocchio’s statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni (fig. 1).[2] Part of the attraction of this sculpture may be its novelty to Thea: unlike the other casts mentioned, Thea is not already familiar with it. Moreover, the statue’s expression—cruel, not calm or composed—is notably different from that of the other casts. But clearly there is more to it than that. Cather’s description of Thea “walk[ing] round and round this terrible man” suggests the extent to which Thea is drawn to this cast, as does her sense that “she had to make some momentous decision about him.” Thea is in the early stages of her education as an artist; Harsanyi thinks of her as one of the most “intelligent” but also one of the most “ignorant” of his pupils (446). It is not surprising, then, that Thea cannot explain her own fascination with this statue, and does not even try to.

Her interest in the “evil, cruel-looking general” is, however, a further manifestation of Thea’s interest in powerful leaders. Earlier in the novel Cather recounted Thea’s purchase of a photograph of a bust of Julius Caesar for her room at Mrs. Lorch’s—a purchase that baffles her landlady but is an extension of Thea’s interest in “Caesar’s ‘Commentaries.’ . . . [S]he loved to read about great generals” (442). Within this context, her fascination with the equestrian statue suggests her recognition and admiration of power, which in turn suggests that she may recognize—if only subconsciously—that power, and even a certain ruthlessness, are also elements in herself that she will need to come to terms with in order to succeed in her profession. Thus her feeling that she needs “to make some momentous decision about” the general, though on its surface illogical, makes sense at a deeper level: she may already intuit that she will someday need to make some difficult decisions, not about him, but about herself. The fact that the leaders who fascinate her—Caesar and the “cruellooking general”—are men is also significant; both exhibit power she does not associate with women. Although she will never, of course, become a military or political leader, her career will require her to make difficult decisions, occasionally decisions that will cause others to see her as hard.

For instance, in a scene Cather implies rather than depicts, Thea decides not

to leave her career at a crucial moment to  Fig. 1. Andrea del Verrocchio, Condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni, c. 1484–1488, bronze,

Campo ss. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, Italy.

Alinari/Art Resource NY.

Fig. 1. Andrea del Verrocchio, Condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni, c. 1484–1488, bronze,

Campo ss. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, Italy.

Alinari/Art Resource NY.  Fig. 2.

Detail return to Colorado to see her

dying mother. Although Thea was in Germany at the time and the trip to see

her mother would have taken her half a year (632), even Dr. Archie fails to

understand her decision; afterward, he may or may not be swayed by Fred

Ottenburg’s explanation that “she positively couldn’t [leave Dresden]. . . .

In that game you can’t lose a single trick. She was ill herself, but she

sang. Her mother was ill, and she sang” (628). Fred’s remark emphasizes the

cost of this decision to Thea herself, both physically (she was ill) and

emotionally (her mother was dying). Thea’s only direct testament to what

this decision cost her comes late in the novel, when she tells Fred that she

can, if she needs to, give up his friendship: “I’ve only a few friends, but

I can lose every one of them, if it has to be. I learned how to lose when my

mother died” (688). Circling the equestrian statue, she may well be

intuiting the cost, both to herself and to others, of power and success.

Fig. 2.

Detail return to Colorado to see her

dying mother. Although Thea was in Germany at the time and the trip to see

her mother would have taken her half a year (632), even Dr. Archie fails to

understand her decision; afterward, he may or may not be swayed by Fred

Ottenburg’s explanation that “she positively couldn’t [leave Dresden]. . . .

In that game you can’t lose a single trick. She was ill herself, but she

sang. Her mother was ill, and she sang” (628). Fred’s remark emphasizes the

cost of this decision to Thea herself, both physically (she was ill) and

emotionally (her mother was dying). Thea’s only direct testament to what

this decision cost her comes late in the novel, when she tells Fred that she

can, if she needs to, give up his friendship: “I’ve only a few friends, but

I can lose every one of them, if it has to be. I learned how to lose when my

mother died” (688). Circling the equestrian statue, she may well be

intuiting the cost, both to herself and to others, of power and success.

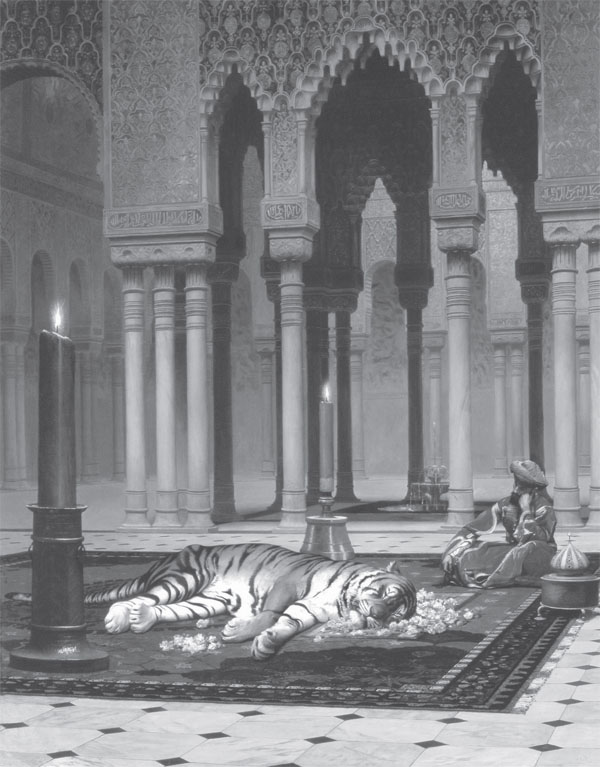

Such a possibility would also explain why Thea eventually finds the casts “gloomy”—and why she is so glad to “r[u]n up the wide staircase to the pictures. There she liked best the ones that told stories” (466), Cather notes. The first is JeanLéon Gérôme’s The Grief of the Pasha (fig. 2), a colorful Orientalist[3] painting that probably would have appealed to Thea not only because of its implied narrative—the Pasha’s beloved pet, a beautiful tiger, has died—but because of its extravagant beauty. Cather describes the painting in detail: “The Pasha was seated on a rug, beside a green candle almost as big as a telegraph pole, and before him was stretched his dead tiger, a splendid beast, and there were pink roses scattered about him” (466). As with many passages in the novel, Cather selects language that reflects the prairie girl’s perspective, particularly the comparison of a candle to a telegraph pole. She also hints that Thea, though she is old enough to be on her own studying music in Chicago, is still a girl in some ways. Cather’s observation in O Pioneers! that “There is often a good deal of the child left in people who have had to grow up too soon” (23) helps to explain why Thea is drawn by this painting, which conveys, regardless of its exotic setting, the relatively simple heartbreak of losing a pet. Gérôme’s painting would be quite appealing to a girl who, having put the provinces behind her, simultaneously wants to see the world and longs for home, as Cather suggests through Thea’s wish that her little brothers Gunner and Axel were there with her to see the painting.[4] Further, this painting is also, like the Bartolomeo Colleoni, a portrait of power—both the Pasha and his tiger—though in this case of power subdued and sympathetic.

The second painting, Jean-François Millet’s Peasants Bringing Home a Calf Born in the Fields (fig. 3), is summarized in a single sentence: “She loved, too, a picture of some boys bringing in a newborn calf on a litter, the cow walking beside it and licking it” (466). This painting also tells a story about an animal, but a simpler, happier one, a story of birth rather than death. At a deeper level, the painting may appeal to Thea because of its portrait of a harmonious family, one that works together: while the mother or older sister looks on, two young men carry the calf toward the barn, where two small children hover in the doorway. Thea’s perception of the two figures carrying the calf as “boys” rather than men (they are adult-sized figures) may suggest that she misses her older brothers, who (at this point in the narrative) have not yet alienated themselves from her; the small children may remind her of the younger siblings of whom she is so fond. Even the cow licking her calf may be a subtle reminder of maternal love (albeit in bovine form) and of all the support Thea has received from her mother. Consciously, however, the implied narrative and the familiarity of the scene are no doubt what appeal to Thea; she feels at home in front of the painting.

In her choice of these paintings, Cather tells us much about Thea’s character

at this point in her development: both seem exactly what might appeal to a

young and unsophisticated girl from Moonstone. The exotic setting of the

Gérôme probably attracts her by its portrayal of a world far from the one

she knows, as well by its expression of a strong but simple emotion; the

Millet  Fig. 3.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Grief of the Pasha, 1882, oil

on canvas on masonite panel, 36 and three eighths x 29 in., Joslyn Art

Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. Gift of Francis T. B. Martin. Used by

permission. may attract her with its homey familiarity.

In both, the narrative element is so strong that the paintings function

almost as illustrations to the “stories” they tell, perhaps not that

different from the “oil-chromos” Thea has seen in Moonstone (cf. Duryea 18),

the painting of Napoleon’s retreat, re-created in cloth, that she admires at

the Kohlers’ (317), or the “large colored print of a brightly lighted church

in a snowstorm, on Christmas Eve,” which, along with her photograph of the

bust of Caesar, hangs in her boardinghouse room (442). Moreover, the glowing

colors of the Millet, along with its depiction of a family that appears to

function more harmoniously than the rather divided Kronborg family, may

encourage Thea to cast a warm glow over her childhood years, allowing her

(or even encouraging her) to miss her family during her first year away from

home. On a more objective level, both paintings use intense colors; they

also emphasize human figures, placing them in the foreground, perhaps

reflecting Cather’s statement in 1894 that “We want men who can paint with

emotion. . . . We haven’t time for pastels in prose and still life; we want

pictures of human men and women” (World and Parish 1:

131; qtd. in Duryea 6). In short, they have an immediate appeal for

Thea.

Fig. 3.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, The Grief of the Pasha, 1882, oil

on canvas on masonite panel, 36 and three eighths x 29 in., Joslyn Art

Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. Gift of Francis T. B. Martin. Used by

permission. may attract her with its homey familiarity.

In both, the narrative element is so strong that the paintings function

almost as illustrations to the “stories” they tell, perhaps not that

different from the “oil-chromos” Thea has seen in Moonstone (cf. Duryea 18),

the painting of Napoleon’s retreat, re-created in cloth, that she admires at

the Kohlers’ (317), or the “large colored print of a brightly lighted church

in a snowstorm, on Christmas Eve,” which, along with her photograph of the

bust of Caesar, hangs in her boardinghouse room (442). Moreover, the glowing

colors of the Millet, along with its depiction of a family that appears to

function more harmoniously than the rather divided Kronborg family, may

encourage Thea to cast a warm glow over her childhood years, allowing her

(or even encouraging her) to miss her family during her first year away from

home. On a more objective level, both paintings use intense colors; they

also emphasize human figures, placing them in the foreground, perhaps

reflecting Cather’s statement in 1894 that “We want men who can paint with

emotion. . . . We haven’t time for pastels in prose and still life; we want

pictures of human men and women” (World and Parish 1:

131; qtd. in Duryea 6). In short, they have an immediate appeal for

Thea.

As with the casts, Thea dismisses—even ignores—some of the great paintings in

the museum. Immediately after describing the Millet painting of the calf,

Cather tells us that Thea “did not like or dislike” the Corot hanging next

to it because “she never saw it” (466). To some extent, she may not “see”

the Corot because Mrs. Anderson, whom Thea dislikes, has waxed enthusiastic

over the painter’s work (465); ignoring the painting is a way of distancing

herself from Mrs. Anderson. An even stronger reason, however, may be the

fact that much of Corot’s work also differs significantly from the paintings

that draw Thea’s attention. Unlike the Millet and the Gérôme, most Corot

paintings do not tell definite stories. Neither do they use the intense

color palette of the Millet and Gérôme; instead, the colors are more

delicate and atmospheric—Thea would probably say  Fig. 4. Jean-François Millet, Peasants Bringing Home a Calf Born in the Fields, 1864,

oil on canvas, 81.1 x 100 cm, Henry Field Memorial Collection, 1894.1063,

Art Institute of Chicago. Photography © the Art Institute of Chicago. “dull”—and oftentimes, figures are small and

set in the middle distance.[5] Even in her disregard of some art, however, Thea

begins to find herself as an artist: she is learning to trust herself and

her own impulses. She has begun to change; like Lucy Gayheart during her

months in Chicago, “the changes were all in the direction of becoming more

and more herself. She was no longer afraid to like or to dislike anything

too much. It was as if she had found some authority for taking what was hers

and rejecting what seemed unimportant” (Lucy Gayheart

698). Thea’s response to art is, as Susan Rosowski has remarked,

“unsophisticated but genuine” (58); finding her genuine self is one part of

Thea’s larger education.

Fig. 4. Jean-François Millet, Peasants Bringing Home a Calf Born in the Fields, 1864,

oil on canvas, 81.1 x 100 cm, Henry Field Memorial Collection, 1894.1063,

Art Institute of Chicago. Photography © the Art Institute of Chicago. “dull”—and oftentimes, figures are small and

set in the middle distance.[5] Even in her disregard of some art, however, Thea

begins to find herself as an artist: she is learning to trust herself and

her own impulses. She has begun to change; like Lucy Gayheart during her

months in Chicago, “the changes were all in the direction of becoming more

and more herself. She was no longer afraid to like or to dislike anything

too much. It was as if she had found some authority for taking what was hers

and rejecting what seemed unimportant” (Lucy Gayheart

698). Thea’s response to art is, as Susan Rosowski has remarked,

“unsophisticated but genuine” (58); finding her genuine self is one part of

Thea’s larger education.

After ignoring the Corot, Thea goes on to the painting that arrests her attention, which is, of course, Breton’s The Song of the Lark (fig. 4). This is the painting that Thea feels is “her picture. . . . That was a picture indeed. . . . She told herself that that picture was ‘right’” (466). Cather then throws down the gauntlet to readers by adding, “Just what she meant by this, it would take a clever person to explain. But to her, the word [“right”] covered the almost boundless satisfaction she felt when she looked at the picture” (466). Yet in issuing a challenge, Cather is also inviting the reader to speculate about why Thea feels so strongly that this is “her picture[,]” a painting that is “right,” and why she takes “almost boundless satisfaction” in it.

To some extent, Thea’s admiration of this painting is on a continuum with her admiration of the other two paintings; like them, it is a narrative—though one even simpler than Millet’s narrative about the calf. In Breton’s, a peasant girl is on her way to the fields at daybreak when she is arrested by the beautiful music of a lark’s song. Yet although it implies a narrative, the Breton differs from the Millet and the Gérôme in an essential way: the two previous paintings depicted their subjects, but here the putative subject is not portrayed. A bird’s song cannot be shown in a representational canvas like this one; the lark itself also goes unportrayed. Instead, the bird and its beautiful song are implied by the girl’s riveted attention, by her stance and her raised face. In short, this brief narrative is a lyrical moment—much like a lyric poem or, for that matter, an aria in an opera, which springs from the opera’s narrative but often freezes time for the duration of a song.

As in the other paintings, in the Breton Thea finds much that is familiar.

Like the Millet painting, the Breton depicts a scene with which Thea, given

her background, is generally familiar: the sunrise over a rural agricultural

countryside. As Rosowski has written, the scene “involve[s] a character’s

possession of her own region” (58); the painting helps Thea claim her native

landscape, much as Cather herself claimed it in writing O

Pioneers! (“My First Novels” 93–94). Even more importantly, Thea may

Fig. 5. Jules

Adolphe Breton, The Song of the Lark, 1884, oil on

canvas, 81.1 x 100 cm, Henry Field Memorial Collection, 1894.1033, Art

Institute of Chicago. Photography © the Art Institute of Chicago. see

herself in the girl. Throughout the novel Cather has made it clear that Thea

is not beautiful in a conventional way, if she is beautiful at all; when she

is in her late teens, for instance, her mother thinks that “She would make a

very handsome woman . . . if she would only get rid of that fierce look she

had sometimes” (488–89). Similarly, Mrs. Nathanmeyer remarks to Fred

Ottenburg when Thea is nineteen that “in ten years she may have quite a

regal beauty, or she may have a heavy, discontented face, all dug out in

channels” (533). Although Thea is not consciously thinking of her own face

as she looks at the girl in Breton’s painting, she sees the peasant girl’s

face as “heavy” (466), making her, one might think, an unlikely candidate

for a portrayal in art; she is no Venus di Milo, nor even a Lily Fisher. At

this stage it may be hard for Thea, much as she loves music, to imagine she

has either the appearance or the ability to become “Kronborg,” an

internationally known singer. In fact, at this point in her development she

has not yet accepted that her greatest potential is not as a pianist but as

a vocalist.

Fig. 5. Jules

Adolphe Breton, The Song of the Lark, 1884, oil on

canvas, 81.1 x 100 cm, Henry Field Memorial Collection, 1894.1033, Art

Institute of Chicago. Photography © the Art Institute of Chicago. see

herself in the girl. Throughout the novel Cather has made it clear that Thea

is not beautiful in a conventional way, if she is beautiful at all; when she

is in her late teens, for instance, her mother thinks that “She would make a

very handsome woman . . . if she would only get rid of that fierce look she

had sometimes” (488–89). Similarly, Mrs. Nathanmeyer remarks to Fred

Ottenburg when Thea is nineteen that “in ten years she may have quite a

regal beauty, or she may have a heavy, discontented face, all dug out in

channels” (533). Although Thea is not consciously thinking of her own face

as she looks at the girl in Breton’s painting, she sees the peasant girl’s

face as “heavy” (466), making her, one might think, an unlikely candidate

for a portrayal in art; she is no Venus di Milo, nor even a Lily Fisher. At

this stage it may be hard for Thea, much as she loves music, to imagine she

has either the appearance or the ability to become “Kronborg,” an

internationally known singer. In fact, at this point in her development she

has not yet accepted that her greatest potential is not as a pianist but as

a vocalist.

But visual art, like literature, has a potentially validating and affirming effect. As Thea stands lost in front of “her picture,” the seeds of that acceptance may be germinating within her. Like the Colorado minister’s daughter, the plain French peasant girl is a provincial “nobody,” yet she has been elevated to the status of art; why should Thea not also be worthy of art? The peasant girl is the focus of many eyes in a museum; looking at her may help Thea imagine that, despite her lack of conventional beauty, she will eventually become the center of the audience’s gaze as she stands upon the stage of an opera house. Thea may divine that she has something superior to conventional beauty; Mrs. Harsanyi sees Thea’s potential “to look strikingly handsome” (450), and Mrs. Nathanmeyer sees “great possibilities” in her appearance (533). (In contrast, Lily Fisher’s conventional beauty dwindles into mediocrity, with Cather describing her in the epilogue as a “fair-haired, dimpled matron” [700]—not unattractive, but decidedly lacking Thea’s ability to be the cynosure of all eyes.)

Yet Thea surpasses the peasant girl, becoming, in terms of Breton’s painting, both the listening girl and the singing lark, functioning not only as the object of the audience’s gaze but also as the creative, active subject—the singer who rivets their attention. The painting evokes the last lines of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “To a Skylark” so strongly that it is hard not to wonder if those lines were echoing in Cather’s mind as she wrote this passage, and perhaps in Thea’s (well read as she is in the romantics) as she stands in front of Breton’s painting: Teach me half the gladness That they brain must know, Such harmonious madness From my lips would flow The world should listen then—as I am listening now. (1035) Surely Shelley’s lines, or even the hint of them in Breton’s painting, would inspire any young singer.

Thea’s experience in the Art Institute, and in particular in front of Breton’s painting, suggests that her trips to the museum provide an important stage in her education. Cather emphasized the need to seize an education in the arts, believing that “the individual can possess the treasure of the world’s great music, literature, and art as his own” (Peck 109–10). In this view she seems very much aligned with those who were, in the period, building and laying out many of the country’s great museums; they believed that the public could educate itself through a study of well-displayed objects (Conn 4). Yet Cather’s portrayal of Thea in the Art Institute implies that such an education does not always mean “going hard at it,” as Fred says of Thea. Sometimes the opposite is true: the most valuable education a museum can offer is for the visitor to wander at will, soaking in the objects that attract him or her and ignoring those that do not. In the Art Institute Thea finds not a school but rather “a place of retreat, as the sand hills and the Kohlers’ garden used to be; . . . a place in which she could relax and play” (465). While the equation between an art museum, a garden, and a geological feature might seem peculiar on its surface (much like Thea’s sense that she needs to make a decision about the general on horseback), it too falls into place. Cather had contemplated calling this novel Artist’s Youth (“Preface” 433); writing a künstlerromanalmost necessitates describing the artist’s earliest introduction to the beautiful, which, for Thea, includes the Kohlers’ garden and the sand hills. Her experience in the Art Institute takes her love of beauty another step; Thea is now seeing and selecting among works that are (unlike the garden or the sand hills) not only beautiful but which, by their very inclusion in the museum, carry the cultural cachet of being designated “art.”

Thea’s fascination with Breton’s painting, her sense of its “rightness” and her sense that it is “her painting,” also lays the groundwork for the next stage in her artistic development: her conscious awakening to the very concept of art in Panther Canyon. In an often-quoted passage, Thea stands in the stream on the floor of the canyon, thinking of the pottery the ancestral puebloans had made to contain the running water: “what was any art but an effort to make a sheath, a mould in which to imprison for a moment the shining, elusive element which is life itself,—life hurrying past us and running away, too strong to stop, too sweet to lose? The Indian women had held it in their jars. In the sculpture she had seen in the Art Institute, it had been caught in a flash of arrested motion” (552). In this passage Cather makes extraordinary connections across time, space, culture, and medium, drawing parallels between Italian Renaissance sculpture, American ancestral puebloan ceramics, and twentieth-century opera singing, and in doing so suggests that there are structures common to very different arts from very different cultures. Although Cather does not mention the Breton painting in this passage, it too possesses this quality; the peasant girl in The Song of the Lark is, like the cruel general, “caught in a flash of arrested motion.” There is much, in short, to account for Thea’s “boundless satisfaction,” her sense that Breton’s canvas is “her picture.”

Imagining the scene that Cather suggests but does not actually describe—Thea frozen in admiration of Breton’s painting, much as the girl in that work is frozen by her admiration of the lark’s song—puts the painting in relation to Cather’s own technique in the final pages of her novel; indeed, if the painting did not serve as an actual inspiration for Cather’s conclusion, it certainly serves as a visual correlative for it. Breton, as we have seen, implies the beauty of the skylark’s song by portraying the peasant girl’s reaction; late in the novel, in her only depiction of Thea’s performance in a major opera production, Cather conveys Thea’s artistry by depicting the reactions of two of her listeners. When the opera begins, Thea’s teacher Harsanyi is impatient, his fingers “fluttering on his knee in a rapid tattoo” (694). Cather keeps her readers wondering, like Mrs. Harsanyi, what he is thinking about the performance of his “uncommon” student; he ignores his wife’s comment that Thea is a “lovely creature” and then “bow[s] his head” and covers his single eye for much of the act (694–95). It is as if the girl in Breton’s painting were unsure about the lark’s song. Only when the curtain goes down does Harsanyi express his enthusiasm, praising Thea’s performance: “At last . . . somebody with enough!” (696). Cather employs the same technique with another member of the audience, Thea’s old friend Spanish Johnny. During the performance he is deeply involved in the music, “praying and cursing under his breath” and “shouting ‘Bravó! Bravó!’ until he was repressed by his neighbors” (698). Cather doesn’t describe Thea’s singing; instead she conveys its beauty through Johnny’s reaction.

Cather may adapt the painting to her own purposes in another way as well. In the penultimate paragraph of the novel proper[6] she describes Johnny as part of the “little crowd” that waits for Thea outside the theater; although the exhausted Thea does not see Johnny, he walks away “wearing a smile which embraced all the stream of life that passed him and the lighted towers that rose into the limpid blue of the evening sky” (699). It is a painterly moment in the text, one in which Cather gives us her own version of Breton’s Song of the Lark—a version in words instead of paint, in which it is evening instead of morning, and in which, in place of the girl enraptured by the skylark, we have Spanish Johnny who has been listening rapturously to Thea’s song. The effect of both songs is the same; and like Breton’s oil painting, Cather’s painterly description draws the inward eye upward, “into the limpid blue of the . . . sky.”

Breton’s Song of the Lark, along with other artworks Cather saw while she was composing her Song of the Lark, may also have influenced Cather’s changing sense of literary aesthetics. As mentioned earlier, Cather came to believe that in The Song of the Lark she told too much (“My First Novels” 96) and that writers, instead of proliferating details, needed to select and simplify (“Novel Démeublé” 37–40). Paradoxically, what a writer creates is not the words on the page but rather “[w]hatever is felt upon the page without being specifically named there . . . . the overtone divined by the ear but not heard by it, the verbal mood, the emotional aura of the fact or the thing or the deed” (“Novel Démeublé” 41–42). Breton’s painting invites the viewer to hear what cannot be depicted, much as Cather’s developing aesthetic was to make the reader “fe[el]” certain things “upon the page without . . . specifically nam[ing]” them. There are notes of this aesthetic much earlier in her work; in 1898, for instance (twenty-four years before the publication of “The Novel Démeublé”), she argued that the nature of English as a language was such that the “Anglo-Saxon . . . learned to mean more than he said, and to make his reader feel it” (World and Parish 2: 583). But it may have been her contemplation of Breton’s canvas that helped her to articulate this principle fully.

An avid viewer and critic of art, particularly painting, Cather saw that although the painting and writing are significantly different media, technique in one could carry over to the other. As a devoted reader of Henry James, she may have well been aware of his remark that “style for one art is style for another, so blessed is the fraternity that binds them together, and the worker in words may take a lesson from the picture-maker” (qtd. in Duryea 17). Certainly Cather was comparing the techniques of literary and visual arts herself by 1900, commenting that Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “insistent use of the silvery green of the olives, of the yellow of the parched clay hills of Palestine . . . reminds me of Pierre Loti’s faculty of infusing absolute personality into environment, if one may compare two such dissimilar mediums as prose and paint” (World and Parish 2: 762). Merrill Maguire Skaggs has remarked on Cather’s association with the American impressionists, noting that from them she may have learned “techniques for capturing motion, mood, color and light that, translated to fiction, helped make her stories so startlingly memorable” (48).

Although Cather only implies Thea standing frozen in front of the Breton (though in doing so she is, of course, demonstrating her ability to create “the thing not named”), and although the notion that Cather herself may have learned from Breton’s canvas is speculative, Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant gives us a concrete example of Cather soaking in a new aesthetic from a painting. When Sergeant returned to New York from France in late June 1913, Cather met her at the boat and “began at once to study with interest” some “canvases and drawings by the Fauve”—even as the customs inspector was still examining Sergeant’s luggage, so intrigued was Cather with this “new way of seeing” (111). Conversations in the visit that ensued took, as one of their topics, one of the newest developments in painting, cubism (119). It was in this period that Cather was writing “Three American Singers,” her important article on Louise Homer, Geraldine Farrar, and Olive Fremstad, and beginning to contemplate writing The Song of the Lark, which she would begin in October 1913 (Woodress 255).

The Cather who wrote The Song of the Lark may have been like Thea in front of the painting—not quite ready to move on to a different style, but taking in concepts of visual art that would eventually shape her own art. Five years after The Song of the Lark she published the short story “Coming, Aphrodite!” One of the two central characters in this story, the artist Don Hedger, has worked with the French painter “C??,” probably a reference to Cézanne, whose postimpressionist experiments with composition moved him in the direction of cubism. When Don shows the aspiring singer Eden Bower some of his own sketches in “C??s” style (perhaps something like Cézanne’s The Bay of Marseilles), she is baffled: “to Miss Bower . . . these landscapes were not at all beautiful, and they gave her no idea of any country whatsoever” (372)—a response that is not surprising in someone who had previously looked only at strictly representational art. Yet Eden’s lack of comprehension and lack of curiosity about this “new way of seeing” are, like her unabashed materialism, a sign of her limitations as an artist. Her attitude suggests that she is the antithesis of Thea in the Art Institute, lost in thought in front of a canvas—or, for that matter, of Cather herself, standing on the dock at New York, staring at the fauvist canvases and beginning to divine the novel that would become The Song of the Lark—absorbing images and concepts that would help her reconceptualize her idea of fiction.