Song of the Lark to air on PBS May 2 and 6

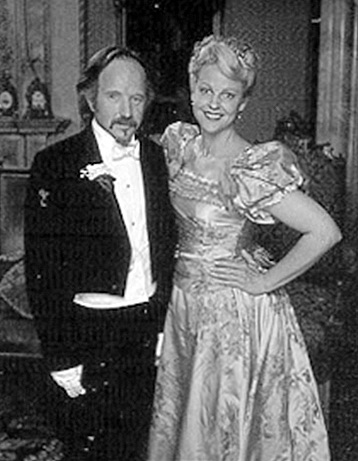

Dr. Archie and Thea on her big

night. Dr. Archie and Thea on her big

night.

|

Among the first scenes in PBS's new film adaptation of The Song of the Lark is Thea Kronborg standing in a field, her face lifted up to the sky, her skirt billowing slightly in the breeze, and an oddly crayoned sun sneaking up in the background. The image, as is soon apparent, echoes Jules Bréton's painting "The Song of the Lark," a reassuring sign that these filmmakers did their homework. Producers Dorthea and June Petrie, director Karen Arthur, and screenwriter Joseph Maurer, who created this film for the new "American Masterpieces" series, demonstrated a respect for the work that they were using. I was encouraged.

And the rest of the film, too, working within budget and time limitations, remains respectful. Though the film does not get at the core of Thea's internal struggle and inevitably robs the story of complexity, it does offer dimensions that add to the experience of Cather's art.

The music, for example, gave sound to what, for many readers, had been merely titles of obscure arias. In finding Lori Stinson to create Thea's voice, the filmmakers filled a tall order, for Thea's voice is supposed to have a distinct beauty and impact, the very qualities of Stinson's voice. To hear Thea sing Glück's "Orfeo" for the Harsanyis is a true pleasure of the film, as it is to hear several other well-performed pieces throughout.

Yet even as the film deepens some of the novel's musical force, it narrows the range of Thea's artistic accomplishments and subsequently the complexity of her character. Wagner, whose music has such a strong place in Cather's climax to Thea's career, is replaced by DvorÁk, and I missed seeing Thea give a full-throttle performance as Sieglinde. By concluding with her recital in Chicago, the film stops short of following Cather's artist into the full possession of her powers as a Wagnerian soprano at the Metropolitan. Ironically, the budget restrictions that forced this decision worked to the film's advantage, for despite the commanding presence of Stinson's voice, Alison Elliott, as Thea, isn't convincing as a singer. She neglects the physical exhaustion that comes from such intense vocal performance (which is unconvincing enough in a drawing room), so seeing her in the Metropolitan would have been comically inappropriate.

Overall, then, Alison Elliott's performance works only if we grant the impossibility of her role. In Cather's novel, Thea's character revolves around her power and force, a gravitas that draws people to her. She is defined by her presence and singular gifts, an artist whose secret is, according to Harsanyi, "passion. That is all. . . . Like heroism, it is inimitable in cheap materials." How do you cast that role? How can you imitate that passion? Elliott manages determination and strength, but she misses the intensity of passion. Her Thea is friendlier than Cather's, more comfortable and conducive to traditional expectations of a movie heroine. Cast within a screenplay that stops before the challenging diva emerges, Elliott's Thea never becomes Cather's Kronborg. Instead, Elliott's character is circumscribed within the congenial script of a talented woman finding success.

Other characters work better, if only because there are fewer demands on them. Maximilian Schell, as Herr Wunch, has a few terrifically dramatic moments. He plays Wunch close to the edge of melodrama, and he pulls it off. The scene where he introduces Thea to Glück's opera is perhaps the first part of the film that pulled me in on its own merits. In that episode, I was no longer watching as a Cather fan curious to see her novel illustrated, but was involved as filmgoer. I understood the "desire" of Wunch's proclamations, and I empathized with the characters as struggling human beings. Schell's scenes made me enter into the story itself and not see it merely as adaptation; I believed it.

Doctor Archie, played by Arliss Howard, also has a credible presence. Howard, helped by his drooping facial hair, is especially effective in Archie's more melancholy moments, as when he accompanies Thea to Chicago and laments the waste of his own life. And Tony Goldwyn, as Fred Ottenburg, wears his clothes like a figure in a men's fashion advertisement. Fred may be reduced to a romantic plot device, but Goldwyn does the job with proper posture and earnestness.

Unfortunately, the character of Ray Kennedy remains disappointingly shallow. In the novel Kennedy, though a sentimental man, remains complex and powerful, a "free-thinker" and self-created human being. In the film, his role is reduced to flat sentimentality, just a chiseled face and "garsh golly" tone that make him ridiculous. Happily, his death scene comes early, so most of the film remains untarnished by his presence.

Also unfortunate was the budget crunch that prevented the filmmakers from doing a location shoot. The novel is, of course, set in Colorado, though most readers regard Moonstone as a thinly veiled version of Red Cloud, Nebraska, so either place could have provided the visualization needed. However, the picturesque hills of Northern California had to stand in for the prairie and desert surrounding Moonstone, and a well-decorated studio backlot for Chicago. As a result, the adaptation's "Moonstone" was largely confined to stuffy interiors and tight shots on facades; the expansive environment of Thea's youth remains unseen, and therefore the loneliness and isolation that she so often feels is not communicated. In the film, she seems surrounded and comfortable.

It's all too common that film adaptations of novels shave scenes and sacrifice complexity, and PBS's The Song of the Lark is no exception. The film remains safe and faithful, insofar as its budget allows; but its "faithfulness" occasionally results in flat translations of the book. Thea's solitary epiphany at Panther Canyon, for example, survives as an awkward conversation with Fred. This scene evokes questions of adaptation: what is the obligation of a film to the book upon which it is based? What constitutes a responsible treatment of the material? By what criteria should we evaluate a film version, once we acknowledge that an adaptation is fundamentally different from the original?

One response to these questions is the recognition that film can create, in its own vocabulary, a reading of a work. This film's reading highlights the struggle of Thea to succeed, making that effort the "core" of the novel, and there is a good argument for that reading. Yet this film makes both her character and her struggle polite in the process. We never get to see the Thea who can't recognize Spanish Johnny's face on the streets of New York City. So, even as the film highlights the struggle, it also changes the character of it, resulting in an adaptation of The Song of the Lark that dodges one of the essential assertions of the novel: that art, in Cather's words, "requires a human sacrifice."

As a viewer, should I resist holding the film to such a standard? After all, this film is ably constructed and produced. But I'm reminded of Tolstoy who claimed, late in his life, that film could accomplish in an instant what it took him pages and pages to accomplish in words, if only the right image is chosen. And I think about Martin Scorcese's evocation of Edith Wharton's work in his adaptation of The Age of Innocence, the way he was able to suggest entire social worlds with a lingering shot of a cummerbund or table setting. Scorcese and countless other filmmakers demonstrate that film has a capable vocabulary to convey rich complexity, a capability not demonstrated in this adaptation of The Song of the Lark.

Andrew Jewell is a Ph.D. student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and serves as co-coordinator of the Cather Colloquium.