A Weird Familiarity of Landscape

Mary Clearman Blew currently teaches creative writing in the MFA program at the University of Idaho. She is the author of numerous essays and books on the West, including Balsamroot, Circle of Women, and Bone Deep in Landscape: Essays on Reading, Writing, and Place.

Mary Clearman Blew. Photo courtesy Micheal-Jean

Impressions, James M. Goble, photographer

Mary Clearman Blew. Photo courtesy Micheal-Jean

Impressions, James M. Goble, photographer

A Weird Familiarity of Landscape

I. What Alexandra Saw.

She had never known before how much the country meant to her. The chirping of the insects down in the long grass had been like the sweetest music. She had felt as if her heart were hiding down there, somewhere, with the quail and the plover and all the little wild things that crooned or buzzed in the sun. Under the long shaggy ridges, she felt the future stirring.

These thoughts occur to Alexandra Bergson in a section of O Pioneers! called "The Wild Land," on the evening after she has returned from a trip away from the Divide, during which she has decided against relocating and, instead, to mortgage the Bergson farm and use the money to expand its acreage. Although her brothers are uneasy about going into debt, they are swayed by Alexandra's arguments, which are based on careful financial calculations, and agree to her plan. What they do not know is that Alexandra's decision to stay on the Divide has to do not only with hard-headed bottom-line calculations, but with her emotional response to the land itself, expressed in the lines quoted above.

It is striking that the repeated verb in these lines is not on what Alexandra sees, but what she feels: "She had felt as if her heart were hiding down there. . . . she felt the future stirring." The other emphasis in the quoted lines is on sound: the chirping of insects like the sweetest music, the little wild things that crooned or buzzed in the sun. In point of fact, nothing is crooning or buzzing in the sun as Alexandra muses on the landscape of the Divide; at the moment she has these thoughts, she is standing under the stars, and to know what she sees, it is necessary to return to the beginning of the passage: Alexandra drew her shawl closer about her and stood leaning against the frame of the mill, looking at the stars which glittered so keenly through the frosty autumn air. She always loved to watch them, to think of their vastness and distance, and of their ordered march. It fortified her to reflect upon the great operations of nature, and when she thought of the law that lay behind them, she felt a sense of personal security. That night she had a new consciousness of the country, felt almost a new relation to it. Even her talk with the boys had not taken away the feeling that had overwhelmed her when she drove back to the Divide that afternoon. She had never known before . . . . (68)

And so on.

Striking in these lines, besides the continued emphasis on feeling, is a sense of movement, from the stars' vastness and distance and ordered march, to the great operations of nature, to Alexandra's own journey and her drive back to the Divide in the afternoon. What Alexandra embarked upon here is not just a physical journey and return, but the process of what the novelist Charles Baxter, in his book Burning Down the House, describes by a term from Russian formalist criticism: defamiliarization, or making the strange familiar and the familiar strange; or a way that a story has, as Baxter puts it, of "[pulling] something contradictory and concealed out of its hiding place" (38). Baxter cites Gerard Manley Hopkins' idea of the "widowed image," an image which has been stripped of some crucial part of its meaning but which retains its traces in misfit detail. Such images, says Baxter, "seem both gratuitous and inexplicably necessary" (40-41). In the case of what Alexandra sees, the stars and their part in the "great operations of nature" function as the widowed image, tangentially connected to Alexandra's musings about herself as a part of nature, but hardly related at all to what she is feeling (her heart hiding "down there, somewhere") or what she is remembering (the sounds of quail, plover, "all the little wild things," during the hours of sunlight).

It is in this moment, when Alexandra sees one landscape (the night sky) and remembers another (the sunlit hills of the Divide), that she recognizes herself, not where she expected to be, but where she suddenly knows she can be found, "under the long shaggy ridges" with their evocation of the barrow-grave which, death-image though it contains, also strangely contains "the future stirring" (69). In this moment, with the strange rendered ordinary and the ordinary rendered strange, we readers recognize ourselves in Alexandra with a shock that emanates, like the future from the shaggy ridges, from its hidden source.

The writer's task is to locate and use, not so much the unexpected details, but those details which don't quite fit their context and which, by their "widowed" nature, release the reader's imagination. "The familiar gives way," says Baxter, "not to the weird but to the experience of a truth caught in midair." But what is the task for all of us, writers or not, who live and breathe and love and worry in a context so loaded with detail, so spinning with color and light and noise, so filled with particles that we have all learned to pick out familiar patterns, to wait automatically at the red light, to walk on green, to listen for dial tone and delete unsolicited e-mail, to screen out television commercials and to mouth platitudes? How, in the chaos of the present, where every breaking news story is shocking, every headline a revelation, every piece of gossip a scandal, every speed set at high and every pitch at fever, even fast-food meals at super-sized, are we to sort through the random and the disconnected to make it from morning until night, let alone to understand our literature and our history? Will the widowed image serve us in any way?

II. What Julius Seyler Saw.

Alexandra's journey reawakens her emotional response to the landscape of the Divide and allows her to re-experience her love for place. Distance from the familiar enables her not so much to see with new eyes as to newly experience the emotions she associates with the landscape of the Divide. Distance from the familiar is recommended to all beginning writers as a way of re-visioning the stale and the ordinary, but often without the proviso that to re-vision is to revise. Which brings me to a distant place, far from my own over-trod trails in the American Northwest: a large lecture room in the German-American Institute, just a few blocks from the Bismarckplatz in Heidelberg, Germany.

The lecture room is white-painted, with a polished granite floor and tall windows full of early sunlight and linden leaves and only the reflections of passing traffic to recall the hurried world of the street. It is a perfect late June morning, and I'm sitting by myself in a row of empty folding chairs, waiting for a symposium to get started. An hour ago I walked over here from the hotel with several professors from the Universtiy of Montana, which is co-sponsoring this symposium with the Center for Foreign Languages and Cultures at the University of Heidelberg. Safe on a sidewalk, we had laughed and held our breaths when an eminent northwest historian and specialist on Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery, carrying a portfolio of maps so large that it blocked his vision, plunged fearlessly into the path of traffic that he could not possibly have seen. Horns honked, but nobody ran over him; he made it here, and so did the rest of us, and now, before the symposium starts, I'm having a moment of pleasurable solitude in public.

"Under Montana's Big Sky: Myth and Reality in the American West" is the title of this symposium. When I was invited to participate, along with several historians, critics, and visual artists from Montana, of course I wanted to attend. A week in Heidelberg in June, talking with old friends, who wouldn't want to come along? I had not visited Germany since the several trips I had made with students from Northern Montana College in Havre in the 1970s, and what I remembered from those visits was grim. We had flown into West Berlin and been body-searched at the terminal under the scrutiny of armed airport guards. A few days later, riding on the subway past barricaded stations under the eastern part of the city, we had heard machine-gun fire. Crossing the Berlin Wall at Checkpoint Charlie, we watched East German guards pass mirrors under cars to look for fugitives, and we saw the gray faces and smelled the gray air on the eastern side of the wall. Later in Munich we stood on the sidewalks while tanks manned by young German soldiers rumbled through the streets in response to some unexplained crisis.

But another conference on myth and reality in the West? Haven't we been talking about this topic long enough?

My first experience in talking about the myth of the West in public had been in 1984, when the Montana Committee for the Humanities had sponsored a conference in Helena called "Sacred Stories, Sacred Cows," and invited Gretel Ehrlich, who had just published The Solace of Open Spaces, and John Cawelti, author of The Six-Gun Mystique, as featured speakers. Cawelti had informed the audience that there were no myths in the West—the West wasn't old enough to have a mythology. His words were like a bad prophecy. The panels and discussions at that conference sparked William Kittredge's and Annick Smith's idea for an anthology of Montana literature. I was on the editorial board that helped to plan that anthology—The Last Best Place—and I took part in many of the discussion groups, readings, and retrospectives that followed its publication. The myth of the West as it was reflected in the works of Montana writers—the romantic, despairing cowboy, the vanishing Indian, the prairie madonna, the westward movement, and the settlement of the frontier—became such a staple of conversation at these events that the phrase began rolling off people's tongues—themythofthewest, one word.

And so, in twenty-eight years, helped along by the work of the revisionist historians and books like Patricia Nelson Limerick's The Legacy of Conquest, I've seen a dramatic shift, from one set of templates to another, in the way that the history and literature of the West is understood. Indeed, my part in this symposium will be to read from my book on the Montana homestead frontier and to present myself during panels and discussions as the genuine article, a woman born and bred in the real West.

I am and am not this genuine article. It's true that my parents were children of the homestead frontier who married and began raising cattle during the depths of drought and the Depression under circumstances of isolation and privation that today could only be sought out on purpose. It's also true that I grew up as a child of ranching on the verge of change. I attended one of the last one-room rural schools. I remember living without telephones or electricity. But I left the ranch when I was seventeen, went to the University of Montana, from there to a Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri, from there to a career as an academic, in these later years as a teacher of creative writing at the University of Idaho. I've never gone back to the ranch. I've never wanted to. Ironically, however, what I fled is what I retain. I am never wholly at ease in crowds or in cities, and I am replenished by periods of solitude, when I can withdraw into myself. Just as now, in this green dapple of linden leaves that cast such a softer-edged shade than the flickering cottonwoods and aspens of the American West, I'm aware of myself as a bubble of associations and sensations; I'm transparent and visible and yet separate and apart, like a spy from another time and place.

The symposium was to have started at nine o'clock, with welcoming speeches from the president of the University of Montana and other dignitaries, but it's nearly nine-thirty, and the audience is still sparse, only thirty or so scattered among the hundred and fifty folding chairs, so I get up and walk around the lecture hall to look more closely at the collection of Julius Seyler paintings that are on loan for the symposium.

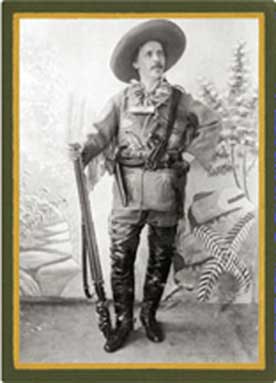

Seyler was a German painter who, around the turn of the century, visited Glacier Park in northern Montana and was fascinated by the contrast of prairie and mountains and by the surviving Blackfeet Indians, whom he coaxed into dressing up and posing for him as they might have appeared at the height of their horse culture, fifty years earlier. The resulting scenes are, in subject matter, much like the paintings of Montana's cowboy artist, Charles M. Russell—buffalo hunters, battle scenes, chieftains in regalia—but without Russell's miniscule, almost photographic, detail. Seyler, half-way between the impressionists and the moderns, used a blunt brushstroke that layers what might have been a simple nostalgia for the past with another tradition's way of seeing the alien or the unique.

At the height of his career, famous world-wide for the novelty and nostalgia of his West, Charles M. Russell exhibited his work in New York and Europe. He is still famous in Montana, for the nostalgia. To view a Russell painting is to eavesdrop on the past as it might have been, perhaps as it should have been. Typically Russell's cowboys and Indians are caught at a moment of dramatic action—the thrashing horse, the downed outlaw, boot caught in his stirrup, the blazing rifles of the approaching posse, the whole rendered in a pure pink and yellow light that illuminates the question. Will the other outlaw, swinging down from his saddle in one fluid, interrupted, and frozen motion, free his friend from the entangling stirrup? Will the fallen horse rise, snorting and ready to run, and will its rider mount and escape?—We'll never know. What we don't get here is sequence, or context, except for the lovingly detailed landscape, sagebrush and distant flat-topped butte and dawn sky; and what matters is the single moment, forever captured, forever lost, themythofthewest, one word.

Seyler, on the other hand, was painting his Blackfeet about the time Charles M. Russell was running away from a middle-class home in St. Louis to become a cowboy in Montana, about twenty years before Russell became famous. Seyler isn't overwhelmed by landscape (as, for example, the Swiss painter, Karl Bodmer, almost a hundred years earlier, painting the white cliffs of the Missouri River as though they are the ramparts of castles on the Rhone, with pronghorn antelope dwarfed in the river below) and Seyler's human figures and horses have familiar proportions (unlike, for example, the strange plunging buffalo on their stems of

legs that George Catlin painted in the 1830s). Seyler's paintings contain as much exactitude of detail as Russell's, although the colors come into focus only as one backs away. Get too close, and the purples and reds begin to swim. Closer yet, and they shape themselves into individual brush strokes, unintelligible. Middle distance is what's called for here, and I'm off-balance at seeing my familiar landscape, the prairie of northern Montana, rendered from such a perspective.

Color is what Seyler sees, and not just reds and purples. I'm particularly drawn to a painting entitled "Hellhounds of the Plains," a kind of motorcycle-gang line-up of young Blackfeet warriors on horseback; I come back to it again and again. Flamboyant slashes of color and energy. No question here of an alien landscape overwhelming the merely human. Also there's no question of the dramatic moment, flight or capture. These guys are front and center, radiating within themselves, lined up and posed, with all the time in the world. And yet I know that they are not what they purport to be. Hellraisers, yes, but they aren't really warriors. If they were, they wouldn't be posing for some German painter with his palette and easel, and in any case, they're fifty years after their time and they know it. They are kids dressed up as warriors, full of themselves and the excitement of their costumery, and whether Seyler sees beyond the color and exoticism of that costumery, sees that these boys are and are not what they seem, whether Seyler has pulled that which is contradictory and concealed out of its hiding place, is doubtful.

III. What Misty Saw.

Heidelberg Castle circa

1620

Heidelberg Castle circa

1620

Heidelberg is a city with a romantic tradition. It is hardly bigger than Boise, Idaho, but it is the seat of one of the great medieval universities, the background for Sigmund Romberg's The Student Prince, a city that people fall in love with. During my first few days here, I have been told five or six times how the city escaped most of the bombing damage that devastated so many other German cities during World War II because the American commander who was directing the bombing raids had spent his own student days vacationing here and could not bring himself to give orders for its destruction.

Today's Heidelberg is not really old by European standards. Most of the medieval city was destroyed during the seventeenth century by the troops of Louis XIV (less tender-hearted, no doubt, than the American bomber commander) and subsequently rebuilt in an eighteenth-century Baroque style. But eighteenth baroque is old enough and lovely enough to enchant my seventeen-year-old foster daughter, Misty, and her friend Tracie, who are my traveling companions. It's the first time in a foreign country for both girls, and they've been excited about their brand-new passports and the German-English phrasebook that they studied during the transatlantic flight, but also they've been apprehensive after my revelation that American appliances, such as hair dryers and curling irons, won't work in European electrical outlets. Fortunately we were able to purchase a current adapter in the Cincinnati airport before we boarded for Frankfurt, so Misty and Tracie will be able to maintain their perfect American hair.

After the hour's ride on the shuttle bus from the Frankfurt airport through flat agricultural land, our first sight of Heidelberg, amid its soft timbered hills along the Neckar River, was a welcome one. When Misty first glimpsed Heidelberg Castle with its towers and turrets and walled gardens looming over the city, she gasped, "It looks like the kind of castle where a knight would ride out to rescue somebody!" And so, once we had checked into our hotel and slept off our jet lag and found a lovely sidewalk restaurant in the shade of linden leaves where we could dine and drink local beer—"Beer! We can drink beer in public here!" cried both girls in delight—we hiked the long trail past hilly suburban gardens full of wrought iron and roses and along a steep pasture where sheep grazed, all the way up to Heidelberg Castle for an afternoon's exploration of romantic ruins, formal gardens and lawns, and a look at the world's largest wine vat. Misty and Tracie constantly were grabbing for their cameras.

Misty has been living with me since her ninth-grade year. The experiences of her childhood differ so much from mine that we might have grown up on opposite sides of the earth instead of in contiguous Rocky Mountain states. She's been a nomad of the urban west, the trailer courts and small-town rentals, a few years in Spokane with her mother, a few months down on the Palouse with her father, a refuge on an aunt's couch, a pad, a split. Hearing of my childhood of four-generation permanence on a Montana ranch, her eyes had widened. "You went to a one-room country school? Really? With an outhouse?"

I had taken my older children with me to Europe, and I wanted Misty to have the same experience, and so we went through the negotiations with Children's Protective Service (we had to have a judge's permission to take her out of the state, let alone out of the country) and got her passport and her ticket. "And can Tracie come along, if she buys her own ticket?" "Sure."

The girls have been good traveling companions. During the three days before the symposium started, they explored Heidelberg with me and did all the tourist things. Along with the Castle, they marveled at the swans on the Neckar River, poked into the expensive shops in the Old Town, climbed the steeple of the Church of the Holy Ghost, and made me sick with vertigo when they casually swung themselves up to sit on the balcony rail to admire the dizzying view and take each other's pictures. ("What's the matter, Mary? We're not going to jump off!")

Now that the symposium has begun, the girls are on their own. They've figured out the money exchange and learned the city bus system, and this morning when I left the hotel, they were planning to visit the Heidelberg zoo. Finally realizing that they can ask the questions in German but that they can't understand the answers, they've given up on the phrasebook and lent it to a professor from the University of Montana, who, to their secret amusement, studies it at odd moments and says he's making good progress.

"My goodness, those girls are independent," is a remark I'll hear all week, and I hope it's a compliment.

We've come to Heidelberg at the height of the white asparagus season, and every menu offers fresh spargus, wonderful, flavorful, mouth-melting spargus, often served with prosciutti and melon. During our luncheon recess from the symposium, at an outdoor café, I order spargus again and ask Dietmar, the young professor of American Studies who has been our guide during the symposium, the question that's been at the back of my mind during the past few days, which I've spent in the company of male academics, more exclusively male academics than at any time since my own assistant professor days.

"Are there any women in your department?"

"Oh, yes," Dietmar assures me. "Oh, yes, there are women. They tend to teach—," he hesitates, searching for the correct term, "—English for practical purposes."

"Business English?"

"Yes. And of course the lower levels of courses."

Dietmar looks flustered, and I hope I haven't embarrassed him with my question. He's such a courteous and self-deprecating young man who has guided us around the university, shown us through the American Studies department, given us generously of his time, and tried to answer all our questions. Later he'll introduce us to his Italian-born wife, who speaks five languages fluently and teaches some of those lower-level courses, and he'll reveal that next year he will have completed his six years at the University of Heidelberg and must look for what he calls a "seat" and which I think must be the equivalent of a tenured position, as difficult to find in Germany as in America.

I have a reason for my question, however. The men in this symposium have been unfailingly friendly, and my friendship with several of them goes back over twenty years. The only problem with them is that they aren't women. Conversations with men are different from conversations when women are present, and I feel a little oxygen-starved, as it were, unsettled beyond being an American in a foreign country, even beyond being a plainswoman who finds her bearings by the horizon and finds herself easily reversed and confused on urban streets.

I'm reminded of James Baldwin, whose essays I first discovered when I was a freshman in college. Drawn by Baldwin's urbanity, by an experience so different from mine, narrated in a voice so reasoned and yet so enraged, I went on to read everything he ever had written, and when I traveled to Europe for the first time, I remembered how Baldwin had winced at the astonishment of Swiss villagers at the sight of his black face. He was the stranger in their village, an alien among people who never had been aliens. "The most illiterate among them is related in a way I am not," Baldwin wrote, "to Dante, Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Aeschylus, Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Racine; the cathedral at Chartres says something to them which it cannot say to me" (148).

During that first raw and windy spring in France, as I wandered through cathedrals whose stones held the chill of centuries, I wondered whether the secrets they kept from a black man from Harlem were the same ones they kept from the white girl from Montana. I admired the light streaming through rose windows, and I was struck, of course, by the sheer size and scale of those edifices, and by the generations of footsteps that had hollowed those stone steps, the layers of candle wax on altars that were so many hundreds of years older than any manmade structures in the Rocky Mountain west. Culturally I was connected to the cathedrals, and to Europe; I had read the literature of the western canon, after all, and I supposed that, as Baldwin himself later wrote, "the fact of Europe had formed us both [the black American and the white American], was part of our identity and part of our inheritance."

Still, I didn't belong in Europe. I simply was not a part of what I saw. I couldn't imagine, cannot now imagine, expatriating myself for the rest of my life, as Baldwin did. And today in Heidelberg it occurs to me to wonder whether, as a western plainswoman, as a woman, I am myself the widowed image.

All travel can be understood as a search for something that has been lost. Whether the journey is one that the body takes through space, or one that the mind takes through time during the sleepless hours, the common thread is the search. Or call it a quest for the Holy Grail or for the Islands of the Blest or for Byzantium; whatever it is that we're looking for, we're preoccupied by it, we can't seem to settle down, and we've woven our restlessness into the plot line of much of the great literature of European culture. The westward journey in particular has been mythologized from classical times as the search for perfection, carried by the conviction that somewhere out there, ever farther to the west, beyond the known and the banal and the overly civilized, beyond the mountains and the seas, beyond the terrors and the monsters and the blurred coastlines of terra incognita, there exists a society without flaws, humankind without sin, and divinity that resides in the natural world.

Rereading O Pioneers! after so many wandering years, I'm particularly struck by its conclusion. Alexandra decides to leave the Divide, to marry Carl, and to travel with him to the Klondike. "Carl," said Alexandra, "I should like to go up there with you in the spring. I haven't been on the water since we crossed the ocean, when I was a little girl. After we first came out here I used to dream sometimes about the shipyard where father worked, and a little sort of inlet, full of masts." Alexandra paused. After a moment's thought she said, "But you would never ask me to go away for good, would you?" (271)

The masts of ships! What are they doing in this elegiac passage, during which Alexandra realizes that she belongs to the Divide, will never in spirit leave the Divide, that the Divide will one day receive her heart into its bosom. So why the masts of ships?

It may be true—although not, I think, in the case of Alexandra Bergson, whose eyes are focused on the red sun in the west, who plans to travel further west, whose images of west and weariness suggest that final sleep which will unite her with the Divide—that the journey back in time, the retracing of footsteps, the revisiting of an old landscape, is a mission of recovery. Maybe it's the self as terra incognita, or maybe we just want to relive our lost youth, awaken memories, or discover our roots in the old country, as those first-generation prairie homesteaders referred to their birthplaces, Czechoslovakia or Croatia or Switzerland or Germany or Sweden, the old countries that glowed rosier with the telling and the passing years and sent children and grandchildren traveling back over the Atlantic with cameras and letters of introduction to distant cousins.

But not for Alexandra Bergson, and not for me. Although my genetic and cultural heritage is European, my emotional response is a blank when it comes to the westward search for an Elysium or the easterly return to the wellsprings. On the one hand, I know too much about the history of white settlement in American and my family's hundred years of homesteading in Montana to believe in Elysium. On the other hand, too many generations have intervened for me to feel a connection with Europe. I'm an ethnic nada.

The afternoon session of the symposium begins with a University of Montana art historian's lecture on Julius Seyler, followed by my reading. Given the theme of the symposium, I've chosen to read an essay about my grandmother's homesteading days in winterbound Montana, which I wrote ten years ago and which I now realize is too long ago to resonate, for me, at least. But it's too late now, and I read on, trying for some dramatic if not emotional spirit. The thirty-below-zero Montana weather that I describe is an odd contrast with the beautiful June afternoon reflected in the tall windows of the lecture hall, and I remember reading the same essay during a blizzard in Moscow, Idaho, and how the audience shivered as I read. This audience just sits and listens. Afterward, several of the professors are good enough to tell me how much they enjoy my work, and some even buy books at the table at the back of the lecture room, but I don't see or hear any interest from the German students. Maybe it's me, or maybe gritty homestead Montana is beyond them or simply boring. Later a panel of German students will be discussing their travel experiences in the American west, and I'm looking forward to hearing their perceptions.

So what am I looking for in Heidelberg? A glimpse of myself, I suppose. A furtive glance at my own reflection in a shadowed shop window, and that reflection not from cultural ties or genetic roots, but from that myth by which Europeans have understood the place where I live and the people who live there. Me, in short.

My story is not, of course, the story assigned to me by others. And yet that assigned story has had its effect upon me. One of the enduring qualities of myth is its capacity to join those who otherwise would float, separate and rootless and disconnected by gender or race or provincialism or language or upbringing or expectations, islands unto themselves, bubbles of perception drawn to touch others but fearful of bursting against the hardened surface. James Baldwin described being falsely accused of stealing someone's bedsheets, arrested and thrown into a Paris jail: "I had become very accomplished in New York at guessing, and, therefore, to a limited extent manipulating to my advantage the reactions of the white world. But this was not New York. None of my old weapons could serve me here. I did not know what they saw when they looked at me . . . . I was not a despised black man. They would simply have laughed at me if I had behaved like one. For them, I was an American."

Which brings me to a secret memory I have of Germany, perhaps the memory which impelled me to bring Misty with me to Heidelberg. It was a moment in Berlin, in March of 1975, a morning of bitter wind and intermittent lashing rain. We—twenty college students, plus my daughter Elizabeth, then fourteen years old, and I—were waiting to pass through Checkpoint Charlie to east Berlin. For warmth we had all crowded into a tiny shop on the west side of the wall, the only viable establishment in sight. As I try to describe it, the interior of that shop seems more and more like the interior of a dream: poorly lit, with a single counter, and a wood floor hollowed by years of footsteps, imbued with the odor of apples and tobacco, like the odor of long-vanished corner groceries of my childhood. The young man behind the counter spoke no English, and none of us spoke German, but the American students sorted out coins and made small purchases, cigarettes, chocolate, and Coca-cola, and ran back out into the fine, sharp rain. But my daughter's attention was drawn to a very old German shepherd dog, gray-muzzled and nearly blind, that lay in a corner with its head on its paws.

Elizabeth was always the animal-loving child. She held out her hand and let the old dog sniff her fingers. Its tail thumped the floor, and it raised its head to have its ears scratched. I glanced at the young man behind the counter—I remember a very white face, with the drawn expression I associate with chronic pain, but perhaps it was only the effect of the inadequate lighting—or perhaps my unconscious revision of the memory over years—and I saw his face soften into a smile as he watched my daughter pet his dog.

What will Misty see? What will she remember?

An old friend of mine, a professor of literature from the University of Montana, speaks on "Montana's Literary Tradition: Between Myths and Realities," with A.B. Guthrie, Jr.'s The Big Sky as his primary text. It's familiar material to me, but it's been several years since I've heard my friend speak on The Big Sky, and during those years he's immersed himself in the study of ecology, writing a book about the effects of clear-cut logging in Borneo and re-defining his views of Montana literature by giving it a Marxist spin. Today, speaking directly to the students in the audience, he contrasts a romantic primitivist love of nature with an ecologist's commitment to bio-diversity, arguing that ecology is the first use of Renaissance empiricism to question the notion of progress, and positing a way we can bring our reading of western American literature from escapism to conservation. "Boone Caudill [Guthrie's ultimate mountain man] was a worker on a beaver plantation while fancying himself an Indian and a wild man," says my friend, summarizing his description of the frontier as the edge of an expanding market, and adds that Guthrie's central theme, we kill what we love, is true because capitalism is the opposite of a sustainable economy.

In the late afternoon, a panel of German professors gather to discuss their topic, "German Perspectives on Montana and the West." From their exchanged glances and humor, I suspect they've been as bemused by the topic as we have been. And at first what we hear is unremarkable: some general talk of open spaces, a reference to Bavarian mythology, a litany of striking American place names.

But then a new phrase turns up: the weird familiarity of landscape. This weird familiarity derives, says one of the professors, from a mid-nineteenth century German tradition of "western" literature, in which German novelists followed the conventions of James Fenimore Cooper by describing the conflict of good and evil on the frontier, with Indians categorized as "good" or "bad" depending on the requirements of the plot; and I gather that a weird familiarity implies a distorted vision of landscape, perhaps a landscape overlaid by weird expectations. A typical element of these nineteenth-century German novels, says the professor, is a hero endowed with superhuman qualities of knowledge and skills; and he cites one protagonist who, debilitated with fever, nevertheless manages to rescue his dog from an alligator, and then, armed only with a knife, defeats three grizzly bears by getting them to fight one another.

Everyone laughs.

Karl

May

Karl

May

Then another professor begins to talk about Karl May, and the audience brightens. It's plain that the novels of Karl May were everyone's favorite childhood reading. In fact, says the professor, Karl May was the favorite author of both Albert Einstein and Adolf Hitler. Hitler's devotion to Karl May extended beyond childhood. He possessed his own specially bound collection of May's complete works, and he tried to convince all his officers to carry copies of May novels with them on the Russian Front, because, he said, "The Russians fight like Indians. They hide behind trees and shot at people."

Themythofthewest, one word. It is precisely that mythic quality that has fascinated Germans with the American West. I first heard of Karl May from a German-born friend who told me about his boyhood reading of May novels by flashlight, under the bedcovers at night. My friend described German-made "western" movies in which Indians, played by German cavalrymen, would come galloping up, leap off their horses, and click their heels. Several years later the German-born novelist Ursula Hegi told me that, as a homesick student in American, she had asked her father to send her her Karl May novels, which she had read as a child by flashlight under the bedcovers at night. (Reading by flashlight under the bedcovers at night turns out to be a common denominator in German children's experience of Karl May; I heard several testimonials to that effect from members of the symposium audience that afternoon.) "Of course," Ursula said, "after my father went to the trouble of sending them, I began rereading and realized just how terrible those novels were."

Karl May's novels, one of which has recently been reprinted by Washington State University Press, were written during the latter part of the nineteenth century and set in an American west that May never visited. Although May is often described as the German equivalent of Zane Grey or Louis L'Amour, his novels owe much of their romantic vision of the frontier to the Leatherstocking tales. May's most popular character was a German emigrant and Indian scout called Old Shatterhand, who, with his faithful Indian companion Winnetou, were cast very much in the mold of the Deerslayer and Chingachgook, but, according to Gerald Nash, with "a strong resemblance to traditional German mythic heroes." Apparently they also have a strong homoerotic quality. No women allowed, of course, on the romantic frontier. I've never read a Karl May novel. I'll take Ursula Hegi's word for their quality, but I've seen a truly alarming cover of an Old Shatterhand comic book that depicts Indians in eagle-feather warbonnets, dancing around a totem pole in front of a pueblo. One of the Indians in the foreground looks as though he has had his teeth filed.

The weird familiarity of landscape. I think Charles Baxter is right when he argues that, for a writer, the aesthetics of shock and surprise, the search for the weird and the novel, are likely to lead to the banal and the bland, where, finally, nothing is novel and the unconventional becomes a convention. But what about the familiar landscape seen through the filter of the unfamiliar gaze? Seyler's paintings, for example? Or the paintings of Charles M. Russell, for that matter? Both Seyler and Russell left home in search of novelty, of color, which they painted. The sense of weird familiarity is mine, viewing the paintings, just as the German professor found a weird familiarity in western American landscapes after reading the novels of Karl May.

Like painters, writers constantly leave home. Unlike painters, the writers seem constantly to be looking back over their shoulders: James Baldwin in Paris, writing novels about New York, Ursula Hegi in Spokane, Washington, writing novels about village life in Germany, Willa Cather in New York, looking back at Red Cloud and the Nebraska prairie. It occurs to me that the writers may be looking for ways deliberately to widen what the cultural geographers call the cognitive gap, that distance between our perception of place and place itself, as a way of objectifying that which otherwise is too close, too drenched in association. Or maybe for writers it's the sudden backward glance, the stolen glimpse that hopes to catch place unaware, reflected darkly through the foreign lens, to see landscape as it is and not as we imagine it to be. If there is a widowed image here, it lives in that split second, that lightning glance.

On Sunday after the close of the symposium, a pleasure boat cruise up the Neckar River has been arranged for all the participants, and I persuade Misty and Tracie to come along. They've avoided the symposium until now, but the shops are closed on Sundays, and they have little else to do. Also, they're tired; they've been enjoying the pleasures of Heidelberg at night, dancing and music and beer. Dressing for meetings in the mornings, I've been stepping over their sleeping bodies in the narrow space of our hotel room, accidentally walking on their gear, their piles of clothes and make-up and hairspray and towels and souvenirs, and I've been finding mysterious offerings left outside our door, roses and chocolates that I'm pretty sure are not meant for me.

And so, bleary-eyed at such an early start, Misty and Tracie walk over to the Bismarckplatz with me to catch the bus to the village of Neckargemund, about thirty miles from Heidelberg, where we wait on the boat docks with other exhausted participants. The medieval streets and houses of Neckargemund survived the attacks by French armies that destroyed Heidelberg in the seventeenth century, and the girls are awakened, then enchanted at the sight of half-timbering, cobblestones, crooked steps and rose gardens and window-boxes of flowers and ancient church spires. Remembering Misty's remark about knights riding out of Heidelberg Castle, I realize that it's a fantasy familiar from their childhood reading, a fairyland that they think they're seeing, not high-priced real estate.

The cruise boat, when it finally arrives, takes us under the Bridge Gate with its portcullis and twin towers, away from Heidelberg and into increasingly romantic scenery. Forested hills mound on either side of the river, rising into cliffs and ramparts as the current narrows. When the cruise boat docks at a village and allows us time to explore, Misty and Tracie are good sports about hiking up a narrow cobblestoned lane to visit a medieval church. They are more interested than I would have expected in the mosaics, the statuary and stone carvings and gold, and they are in awe at the age of the church. Fairyland, I think again.

Eventually we return to the cruise boat and shiver in the increasingly cool air lifting off the water until, farther up-river, we enter a series of locks. As we wait in the brick-and-moss-lined shaft for the water to rise and float us into the next level, the eminent historian from the University of Montana comes over to Misty and Tracie and asks, "Do you know what kind of birds those are?"

The birds are a small cluster on the wall opposite us, sparrows most likely, fluttering and digging into the moss.

"No," says Misty, finally. "What kind are they?"

"They're lock moss nesters."

The professor retreats, laughing. The girls stare after him.

After the cruise, we've been invited to a reception at the home of one of the German professors who lives in Neckargemund, but Misty and Tracie have had enough of professors. They want to go back to Heidelberg and enjoy their last night on the town.

"Do you know how to catch the bus from Neckargemund?"

"Oh, yes," and off they go, back into a world comprised of the two of them.

"My, those girls are independent," says somebody, and again I hope it's a compliment.

What are the images that Misty and Tracie will retain from this trip? What will be their secret memories? (A year later I'll ask Misty, and she'll say, without hesitation, "The churches. The artwork in the churches. And the spire we climbed with you.")

For me it will be a moment in the symposium, during a panel comprised of German students who have studied or traveled in the West. Most of their perceptions were predictable. Space and sky. Buffalo. Contemporary Indians (a disappointment.) But then a young man showed a short black-and-white video he had made, and suddenly I was alert, because after he had filmed what he expected to see, the cowboy hats and the false fronts and the Cadillacs tethered to hitching racks, he began to see. His final shot was a long view of some small Western town, anonymous, unpopulated, and stark between sod and weather. He had caught the fragility of all human construction in the American West, the colonizer's lack of history, the sense that the winds might at any time blow that town with its empty wide main street and its parked trucks and its three grain elevators off its shallow roots and into oblivion. For that moment, in that insubstantial image on film, that lightning glance, I, too, saw the weird familiarity of landscape.