McClure's Magazine

by Willa Sibert Cather

From McClure's Magazine, 42 (February 1914): 76-87.

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY

IN THE FIRST FOUR CHAPTERS OF HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY MR. MCCLURE TOLD OF HIS EARLY CHILDHOOD IN IRELAND, THE DEATH OF HIS FATHER, AND HIS VOYAGE TO AMERICA, WHEN HE WAS NINE YEARS OLD, WITH HIS MOTHER AND YOUNGER BROTHERS; OF THE FAMILY'S STRUGGLE FOR A LIVELIHOOD IN THE NEW COUNTRY; AND OF HIS OWN EFFORTS TO GET AN EDUCATION. WHEN HE WAS SEVENTEEN HE WENT TO KNOX COLLEGE, IN ILLINOIS, AND WORKED THROUGH SEVEN YEARS OF PREPARATORY AND UNDERGRADUATE WORK. DURING THIS TIME HE BECAME ENGAGED TO HARRIET HURD, DAUGHTER OF THE HEAD OF THE LATIN DEPARTMENT AT KNOX; BUT THEIR MARRIAGE WAS FOR A LONG TIME STRONGLY OPPOSED BY MISS HURD'S FATHER.

WHEN I left Galesburg at the end of June, 1882, and started for Utica, New York, to find Miss Hurd, I was really leaving the West for good, but I did not know it then. I left very casually, without saying good-by to anyone, thinking that I would be back in a few weeks, perhaps. Or perhaps I did not really think about it at all. I simply got on the train for Chicago. One seldom realizes the critical moves in one's life until long afterward. And, though I lived so much in the future, I never looked ahead and planned; I finished one thing and did the next. The train on which I left Galesburg was headed straight for Life and Work and the Future; but I had no realization of this then.

I arrived at Utica, New York, June 30, 1882, early in the morning. I caught the first train out for Marcy, where Miss Hurd was visiting her friend Miss Potter, an old schoolmate at Berthier-en-Haut. When I reached the house I was met by Miss Potter, who told me that Miss Hurd would prefer not to see me. I urged my case, however, until Miss Hurd consented to see me. My interview with Miss Hurd was almost too painful to describe here, and more than justified the fears that the ceasing of her letters had aroused in me. When I left her, I carried away the conviction that she had absolutely ceased to care for me—that I in every way displeased her and fell short of her expectations.

This dismissal I accepted as final. I walked back to the station at Marcy, and found that there would be no train for Utica for some time; so I walked on along the railroad tracks to Utica. Once, when I was walking along at the bottom of a cut, I heard a train coming behind me; for a moment I thought that it was not worth while to get out of the way.

My Arrival in Boston

When I reached Utica, I went to the station-master and asked him how soon there would be another train out. " Half an hour, " he replied. I asked him where it went. He answered, "To Boston." So I asked him to give me a ticket to Boston. I had never in my life thought of going to Boston before, and I had no reason for going there now. I was merely going wherever the next train went, and as far as it went. Then I looked about for my valise, which contained all the clothing I had brought, as well as my stock of peddler's supplies. It was nowhere to be found, so I boarded the Boston train and went on without it.

I reached Boston late that night, and got out at the South Station in the midst of a terrible thunder-storm. I knew no one in Boston except Miss Malvina Bennett (now Professor of Elocution at Wellesley), who had taught elocution at Knox. She lived in Somerville, and I immediately set out for Somerville. If I had had my wits about me, I should not, of course, have started for anybody's house at that hour of the night. The trip to Somerville took more than an hour, and I had to change cars several times on the way. When I got to Miss Bennett's house, I found it open, and the members of the household, some of them at least, were up and dressed, on account of the serious illness of Miss Bennett's mother. I was taken in and made welcome, and for several days Miss Bennett and her family did all they could to make me comfortable and to help me to get myself established in some way. I remained with the Bennetts Saturday and Sunday. I had only six dollars, and this hospitality was of the utmost importance to me.

I Go to Colonel Pope and Ask for Work

My first application for a job in Boston was made in accordance with an idea of my own.

Every boy in the West knew the Pope Manufacturing Company and the Columbia bicycle—the high, old-fashioned wheel which was then the only kind in general use. When I published my "History of Western College Journalism" the Pope Company had given me an advertisement, and that seemed to me a kind of "connection." I had always noticed the Pope advertisements everywhere. Everything about that company seemed to me progressive. As I learned afterward, it was a maxim of Colonel Pope's that "some advertising was better than others, but all advertising was good."

Monday the 3d of July was one of those clear, fresh days very common in Boston, where even in summer the air often has a peculiar flavor of the sea. I took the street car in from Somerville, and got off at Scollay Square. From there I walked a considerable distance up Washington Street to the offices of the Pope Manufacturing Company at 597, near where Washington crosses Boylston. I walked into the general office and said I wanted to see the president of the company.

"Colonel Pope?" inquired the clerk.

I answered: "Yes, Colonel Pope."

Colonel Pope's Career

I was taken to Colonel A. A. Pope, who was then an alert, progressive man of thirty-nine. He had been an officer in the Civil War when a very young man, and after he entered business had, within a few years, made a very considerable fortune in manufacturing leather findings. Some years before this a Frenchman named Pierre Lallemont had taken out a patent for wheels driven by pedals attached to the axle the basic patent of the bicycle. Colonel Pope saw the possibilities of this patent, and bought it. Though his patent right was continually being contested, and he had constantly to employ several patent lawyers to protect it, he held it until it expired, and every other bicycle manufacturer had to pay Colonel Pope a tax of ten dollars on every wheel they manufactured.

I told Colonel Pope, by way of introduction, that he had once given me an "ad" for a little book I had published. He said that he was sorry, but they were not giving out any more advertising that season. I replied respectfully that I didn't want any more advertising; that I had been a college editor, and now I was out of college and out of a job. What I wanted was work, and I wanted it very badly.

A Job that I Had to Have

He again said he was sorry, but they were laying off hands. I still hung on. It seemed to me that everything would be all up with me if I had to go out of that room without a job. I had to have a job. I asked him if there wasn't anything at all that I could do. My earnestness made him look at me sharply.

"Willing to wash windows and scrub floors?" he asked.

I told him that I was, and he turned to one of his clerks. "Has Wilmot got anybody yet to help him in the downtown rink?" he asked.

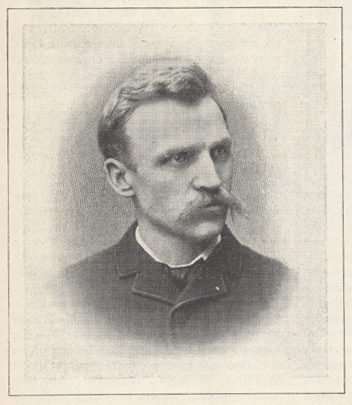

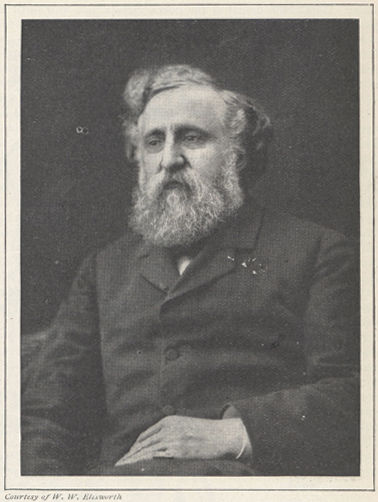

MR. MCCLURE in 1884, the year that he started his newspaper syndicate in New York

MR. MCCLURE in 1884, the year that he started his newspaper syndicate in New York

The clerk said he thought not.

"Very well," said Colonel Pope. "You can go to the rink and help Wilmot out for to-morrow."

The next day was the Fourth of July, and an extra man would be needed for that day.

I Learn to Ride a Biicycle

I went to the bicycle rink on Huntington Avenue, and found that what Wilmot wanted was a man to teach beginners to ride. Now, I had never been on a bicycle in my life, nor even been very close to one; but I was in the predicament of the dog that had to climb a tree. In a couple of hours I had learned to ride a wheel myself and was teaching other people.

Next day Mr. Wilmot paid me a dollar. He did not say anything about my coming back the next morning; but I came, and went to work, very much afraid I would be told that I wasn't needed. After that Mr. Wilmot did not exactly engage me, but he forgot to discharge me, and I came back every day and went to work. I kept myself inconspicuous and worked diligently. At the end of the week Colonel Pope sent for me and placed me in charge of the uptown rink, over the general offices of the Pope Company on Washington Street.

Colonel Pope was a man who watched his workmen. I had not been mistaken when I felt that a young man would have a chance with him. He used often to say that "water would find its level," and he kept an eye on us. One day he called me into his office and asked me if I could edit a magazine.

"Yes, sir," I replied quickly. I remember it flashed through my mind that I could do anything I was put at just then—that if I were required to run an ocean steamer I could somehow manage to do it: I could learn to do it as I went along. I answered as quickly as I could get the words out of my mouth, afraid that Colonel Pope would change his mind before I could get them out. Then I added: "I could edit a monthly; I hardly think I could manage a weekly."

Then he told me that they were about to start a magazine, to be called the Wheelman, devoted to bicycling. I sent to Galesburg and got a file of the college paper I had edited, to show him what I could do in that line. When I was in college I had never read magazines. They were too expensive to buy. It had always seemed remarkable to me that a man could ever feel rich enough to pay thirty-five cents for a magazine.

After I began to know John Phillips, in my junior year, and began to go to his house, I found magazines there. I remember one night taking up a copy of the Century Magazine and beginning the new serial, which happened to be "A Modern Instance," by Mr. Howells. That was the first serial I had ever read, and I followed it to the end with intense interest. In doing so I became fairly well acquainted with the Century Magazine.

When Colonel Pope was planning the first number of the magazine he was going to publish, I remembered having read an article on bicycling in the Century, called "A Wheel Around the Hub," which I thought would make an excellent article to open the first number of the Wheelman. I told Colonel Pope about it, and he sent me over to New York to buy the plates of the article and the right to republish it. I bought the plates for three hundred dollars, and took them back to Boston. When the question of the make-up and typography of the Wheelman arose, here I had the first article of the opening number in one kind of type; it would certainly be absurd to have the rest of the magazine in another. Since the Century was notably the best American magazine typographically, I did not see why we should not adopt the Century idea of make-up throughout. So, when the first number of the Wheelman appeared, it looked exactly like the Century—somewhat to the astonishment of the publishers of the latter magazine, who had not intended to sell me their idea of make-up along with the plates of the article on bicycling.

As soon as plans for the Wheelman were fairly under way, it became clear that we would need a couple more men. I talked

to Colonel Pope about John Phillips and my own brother John, and he told me to go

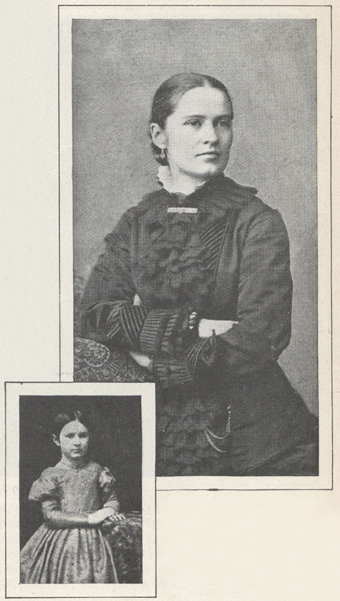

HARRIET HURD, who became Mr. McClure's wife after an engagement of seven years; from photographs

taken when she was eight years old and when she was twenty-four ahead and send for them. The boys came on from Galesburg, and in a few weeks the

three of us were established in offices at 608 Washington Street, near Colonel Pope's

own offices.

HARRIET HURD, who became Mr. McClure's wife after an engagement of seven years; from photographs

taken when she was eight years old and when she was twenty-four ahead and send for them. The boys came on from Galesburg, and in a few weeks the

three of us were established in offices at 608 Washington Street, near Colonel Pope's

own offices.

How I Accidentally Became an Editor

The first number of the Wheelman came out in August, 1882, within two months after I left college, and, quite by accident, I was the editor of it. I had never expected to be an editor, or planned to be one; but now that I found myself one, I was not surprised. Before I knew it I had grown up, acquired responsibilities.

Up to this time I had always lived in the

"MR. THEODORE L. DEVINNE, founder of the De Vinne Press, was then and is to-day one of the world's foremost

experts, a wide scholar as well as great printer. I was entered on his pay-roll as

an expert printer at wages of eighteen dollars a week. To give me a chance, Mr. De

Vinne paid me seven dollars extra every Saturday night out of his own pocket" future and felt that I was simply getting ready for something. Now I began to live

in the present. I had always regarded my occupations in college as temporary, and

when I finished college I had not allowed myself to fall back on any of those temporary

means of support in which boys take shelter while they look around. I felt now that

I had managed to attach myself to something vital, where there was every possibility

of development. I was in the big game, in the real business of the world; and I began

to live in the present.

"MR. THEODORE L. DEVINNE, founder of the De Vinne Press, was then and is to-day one of the world's foremost

experts, a wide scholar as well as great printer. I was entered on his pay-roll as

an expert printer at wages of eighteen dollars a week. To give me a chance, Mr. De

Vinne paid me seven dollars extra every Saturday night out of his own pocket" future and felt that I was simply getting ready for something. Now I began to live

in the present. I had always regarded my occupations in college as temporary, and

when I finished college I had not allowed myself to fall back on any of those temporary

means of support in which boys take shelter while they look around. I felt now that

I had managed to attach myself to something vital, where there was every possibility

of development. I was in the big game, in the real business of the world; and I began

to live in the present.

Colonel Pope's office, 597 Washington Street, was set back a little from the street; when you mounted the steps to enter the front door, you could not see the street down which you had come. It was just at that crook in the street that I said good-by to my youth. When I have passed that place in later years, I have fairly seen him standing there—a thin boy, with a face somewhat worn from loneliness and wanting things he couldn't get, a little hurt at being left so unceremoniously. When I went up the steps, he stopped outside; and it now seems to me that I stopped on the steps and looked at him, and that when he looked at me I turned and never spoke to him and went into the building. I came out with a job, but I never saw him again, and now I have no sense of identity with that boy; he was simply one boy whom I knew better than other boys. He had lived intensely in the future and had wanted a great many things. It tires me, even now, to remember how many things he had wanted. He had always lived in the country, and was an idealist to such an extent that he thought the world was peopled exclusively by idealists. But I went into business and he went back to the woods.

The Wheelman, when it appeared, as I have said, looked like a thinner Century. It had eighty pages of text and as many pages of advertisements as we could get. It was illustrated with wood engravings—that was before the days of half-tones—and sold for twenty cents a copy. We paid for contributions, but our contributors were oftener professional men—doctors, lawyers, ministers—than journalists or professional writers.

Bicycling was the first out-of-door sport that became generally popular in America; tennis and golf came later. Town men, who followed sedentary occupations, discovered the country on the bicycle. These enthusiasts sent us articles on everything that had to do with bicycling. Many of the most entertaining were accounts of long trips made through interesting parts of the country, and illustrated with photographs. We had a department devoted to bicycle clubs, and published accounts of meets and races. I spent a good part of my time traveling about to attend these meets and tournaments and getting contributions from enthusiastic wheelmen. Mr. Phillips had general charge of the office.

One of the pleasantest trips I made in connection with my work on the Wheelman was to the home of Harriet Prescott Spofford, at Deer Island, just outside Newburyport. Mrs. Spofford's island was—and is still—all her own, beautifully situated in the middle of the Merrimac River. I rode down from Boston one Sunday to see whether I could persuade her to do some writing for the Wheelman. Mrs. Spofford was a woman of singular charm, tall, slender, with a beautifully shaped face and delicate coloring. I knew her stories well, and she seemed to me everything that a poet should be.

Her cordiality and her quick comprehension of things—it seemed to me that she understood

at once whatever I mentioned to her—made me wish that I could stay there forever.

Before I knew what I was doing, I was telling her all about Harriet Hurd and the sorrows

and discouragements of my long courtship. She seemed to know all about that too, and

I felt at once that I had never talked to any one so responsive. She asked me to bring

Miss Hurd to see her some time, and some months afterward I did, with the greatest

pleasure to both of us. That first visit to Mrs. Spofford began a friendship Courtesy of W. W. Elsworth"MR. ROSWELL SMITH, owner of the 'Century,' was the foremost figure in the magazine world. He strongly

advised me to come to New York, go into the De Vinne printing house, and work my way

up in that profession. He added that if I needed money for the move to New York, I

could draw on him to the extent of a thousand dollars"which has now lasted for more than thirty years.

Courtesy of W. W. Elsworth"MR. ROSWELL SMITH, owner of the 'Century,' was the foremost figure in the magazine world. He strongly

advised me to come to New York, go into the De Vinne printing house, and work my way

up in that profession. He added that if I needed money for the move to New York, I

could draw on him to the extent of a thousand dollars"which has now lasted for more than thirty years.

Although my last interview with Miss Hurd at Marcy was a definite dismissal, I did not entirely give up hope. People never really give up hope when they desire anything greatly. As soon as I got work in Boston, I began hoping for a letter from her. I always went to the post-office down on Devonshire Street every Sunday; for there was no delivery on that day, and, if a letter did come from her, I could not take the chance of its lying over in the office until Monday. I always imagined there was a letter waiting there as I hurried down the street, and at the general delivery window I inquired impatiently, as if I knew it was there. The blank denial of the postal clerk never quite dashed me, and next Sunday I was in just as much of a hurry. At last a letter did come, to tell me she was returning some books I had given her; but the tone of it was friendly enough to make me resolve to try again.

After the Wheelman got fairly started the future looked brighter to me than it had ever looked before, and I began to go up to Andover, where Miss Hurd was teaching in Abbot Academy. I made the acquaintance of Miss Philena McKeen, the principal of the academy, and she became a warm friend of mine. She even urged, when at last Miss Hurd definitely decided to marry me, that we should be married in Andover, at the Academy. For, at last, Miss Hurd did decide.

Our engagement had been off and on now for about six years. She had made every reasonable concession to her father's strong feeling; she had waited, as he besought her to, had gone away from Galesburg, formed new friends, and neither seen me nor written to me for four years. Our feeling for each other had endured through so much, and survived so many vicissitudes, that she at last felt that it would be right to marry me, even against her father's wishes and though she knew that such a decision would cause him the bitterest disappointment.

After she once made up her mind it was the right thing to do, I knew that nothing

could alter her decision, just as I knew that, if she had decided that it would be

wrong, nothing on earth could have made her marry me. Before the spring term of 1883

was over, Miss Hurd wrote her father that she intended to marry me; that, if he wished

her to be married at home, she would go home for the summer vacation and have her

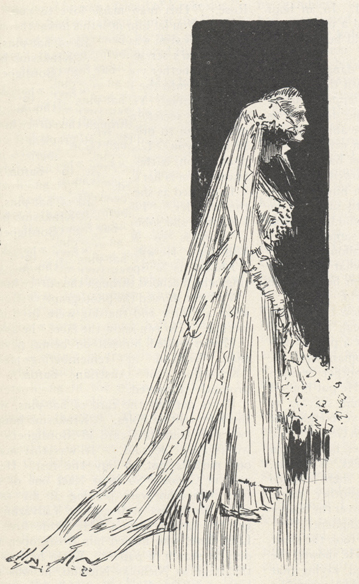

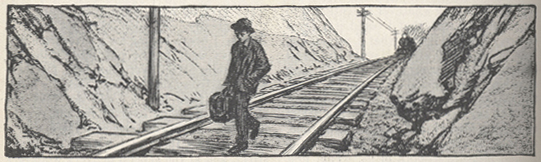

wedding in September. If he did not wish her to be married at home, she would  "FOR A MOMENT I thought that it was not worth while to get out of the way"not wait until fall, but would be married at the Academy, under Miss McKeen's directorship,

as soon as the spring term was over. Professor Hurd wrote that he would rather she

were married at home.

"FOR A MOMENT I thought that it was not worth while to get out of the way"not wait until fall, but would be married at the Academy, under Miss McKeen's directorship,

as soon as the spring term was over. Professor Hurd wrote that he would rather she

were married at home.

During the previous winter, in December, I came down with a severe attack of typhoid fever. I do not remember much about that illness, but Colonel Pope's twin sisters, both practising physicians in Boston, remember it perfectly. John Phillips, my brother John, and I were all living in one room somewhere in Boston. I had not been able to go to work for several days, and the boys reported me to Colonel Pope as ill. He called upon his sisters and told them he wished they would go to see me and do what could be done for me. Miss Pope says that she came to my room and found me well advanced in typhoid. She had me sent to a hospital and put in a private room, and she and her sister often came to see me and kept an eye on my progress. I recovered rapidly, remaining in the hospital only three weeks and two days. Colonel Pope paid all my hospital expenses, as well as my salary during the time I was ill.

My Marriage

It would probably have been better for me had I remained in the hospital longer, for I felt the effects of that illness all summer and my energy was below normal. Miss Hurd went back to Galesburg in June and I had a rather gloomy summer. My physical weakness showed itself in occasional fits of depression. Sometimes I got very far down indeed. At such times I used to feel sure that, although the date for the wedding was then set, it would never come off at all. I used to be overwhelmed by the certainty of losing everything. That summer I experienced the truth of the saying that a coward dies a thousand deaths.

When, at last; I went West to be married, Professor Hurd would allow me to call at the house only once before the actual ceremony. His students used to call him "the old Roman," and up to the moment his daughter left his house he did not disguise his hostility. From the first I had always had a great sympathy with Professor Hurd's attitude, and I understood his feeling better than he knew. I could appreciate his lack of confidence in me, because I had never had any great confidence in myself. I realized perfectly well that he had every reason to expect a better marriage for his daughter. Every one in Galesburg expected a brilliant future for a girl so beautiful and gifted.

Harriet's attainments had been a great satisfaction to her father. In educating her

he had demonstrated some of his pet theories. He had put her to work at Latin and

Greek while she was still a child, and she had acquired an easy mastery of both languages

at the age when most students are beginning them. He had sent her to Berthier-en-Haut

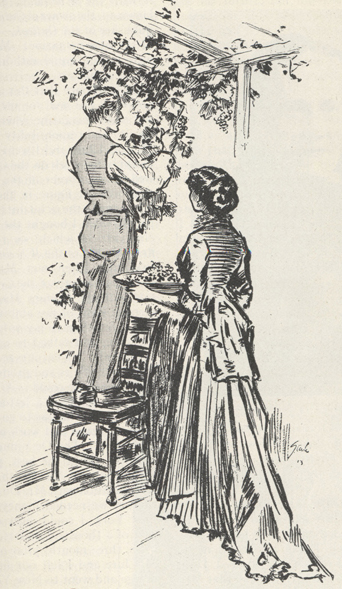

for a year to assure her a fluency in French, and had spared no pains to develop  "WE BEGAN to keep house in a little frame house in Cambridge, where there were lots of ripe

grapes in the back yard, I remember. Our rent took just half my salary of fifteen

dollars a week, and we lived on the other half"a mind unusually gifted. Her beauty, too, and her beautiful speaking voice were matters

of pride to him. It seemed to him that she would be entirely wasted on a visionary

boy like me. All her friends felt the same way. Indeed, when Mrs. Williston, of Galesburg,

first introduced me to Miss Hurd, she said, noticing my absorption when I sat next

to Harriet at luncheon: "Don't cry for the moon, Sam." People in Galesburg tell me

how often they used to notice Harriet Hurd out walking; she was very slender, had

a free carriage, and walked straight, like an Indian girl.

"WE BEGAN to keep house in a little frame house in Cambridge, where there were lots of ripe

grapes in the back yard, I remember. Our rent took just half my salary of fifteen

dollars a week, and we lived on the other half"a mind unusually gifted. Her beauty, too, and her beautiful speaking voice were matters

of pride to him. It seemed to him that she would be entirely wasted on a visionary

boy like me. All her friends felt the same way. Indeed, when Mrs. Williston, of Galesburg,

first introduced me to Miss Hurd, she said, noticing my absorption when I sat next

to Harriet at luncheon: "Don't cry for the moon, Sam." People in Galesburg tell me

how often they used to notice Harriet Hurd out walking; she was very slender, had

a free carriage, and walked straight, like an Indian girl.

Harriet and I were married at her father's house in Galesburg, September 4, 1883, seven years, lacking three days, from the date of our first boy-and-girl engagement. I had asked Harriet then whether, if I turned out to be a good man, she would marry me in seven years. I do not remember much about the ceremony, except that I broke in and said "yes" too soon, and then had to say it over again.

After the wedding we started East, going back to Boston by way of Quebec, where we

spent some delightful days at a little French

"MRS. SPOFFORD was a woman of singular charm, tall, slender, with a beautifully shaped face and

delicate coloring. She seemed to me everything that a poet should be"hotel. I was then making fifteen dollars a week. I had transportation over the railroads

and sixty dollars in cash for my wedding journey, and I was amazed that our week on

the road took it all. Indeed, I was so prudent about that sixty dollars that Mrs.

McClure began to remember with apprehension a certain cautious professor at Knox College

who had kept an itemized account of the expenses of his wedding trip.

"MRS. SPOFFORD was a woman of singular charm, tall, slender, with a beautifully shaped face and

delicate coloring. She seemed to me everything that a poet should be"hotel. I was then making fifteen dollars a week. I had transportation over the railroads

and sixty dollars in cash for my wedding journey, and I was amazed that our week on

the road took it all. Indeed, I was so prudent about that sixty dollars that Mrs.

McClure began to remember with apprehension a certain cautious professor at Knox College

who had kept an itemized account of the expenses of his wedding trip.

We began to keep house in a little frame house in Wendell Street, Cambridge, where there were lots of ripe grapes in the back yard, I remember. Mrs. McClure had saved up three hundred dollars from her teaching, and with this she furnished the house. Our rent took just half of my salary, and we lived on the other half. Everything was going well.

I Go to New York and Apply for Work on the "Century Magazine"

About this time Colonel Pope decided to buy the magazine called Outing and combine it with the Wheelman, making Mr. W. B. Howland, the owner of Outing,—afterward the publisher of the Outlook,—business manager of the new magazine. Mr. Howland and I were to have equal authority in editorial and business matters.

I felt at once that this combination would not work out well for me, and that I could not edit a magazine where I shared the authority and responsibility with another man. Mrs. McClure and I went over to New York to apply for work on the Century. Mr. Roswell Smith, owner of the Century, was then the foremost figure in the magazine world. I had made the acquaintance of the Century people when I bought the plates of the bicycling article which we republished in the first number of the Wheelman, and had since that time often met Mr. Chichester, the business manager of the Century. A connection with the Century Magazine was the uttermost limit of my ambition.

Mr. Smith gave my wife and me a cordial welcome, and talked to us as if he were an old friend. He encouraged us to tell him all about our affairs and promised to give us the best counsel he could. After we returned to Boston I received a letter from Mr. Smith strongly advising me to go into the De Vinne printing house and work my way up in that profession. The De Vinne Press was one of the best, if not the best, printing houses in the world, and Mr. Smith said he could get me a position with Mr. De Vinne. He added that, if we needed money for the move to New York, I could draw on him to the extent of a thousand dollars.

So, three months after our marriage, Mrs. McClure and I left our first home in Cambridge and went to New York. We shipped our household goods, and we went down on a boat of the Fall River Line. It was late in December, and as we passed under Brooklyn Bridge on the morning of our arrival the clouds were heavy in the sky. By the time we landed the rain was falling in torrents and the lights were burning in all the downtown business houses. We had been directed to a miserable little boarding-house near Warren Street, where we were wretchedly uncomfortable for a few days. We soon found more comfortable quarters in a lodging-house at 141 West Fifteenth Street, where we had the parlor floor and the use of the kitchen.

Mr. Smith had got me a place in the De Vinne printing house at twenty-five dollars a week, and he gave Mrs. McClure a posi-tion at fifteen dollars a week on the Century Dictionary, which was then in the course of preparation. She went to her work every day as regularly as I went to mine. Her work was to read American authors and select sentences illustrating the usage of certain words for quotation in the Dictionary. My work at De Vinne's was reading proof and measuring up what the compositors had set. The hardest thing about it was that it kept me on my feet all day, and I was still weak from my illness of the winter before. I felt exactly like a rubber ball that has been burned and lost all its spring. The hours were long; I had to be at the composing-rooms every morning at seven o'clock, and I had only half an hour for lunch. I used to sleep until the last possible moment in the morning, then throw on my clothes, put some rolls and raisins in my pocket, take the elevated at Fourteenth Street, and get down to Murray Street perhaps five minutes late, perhaps fifteen. We were timed as we went in and our tardiness was taken out of our pay. Mrs. McClure and I both worked until six o'clock at night, and then went home dead tired, and cooked our dinner and washed the dishes. Sunday was the only day when we ever saw each other by daylight.

From the first day I entered the De Vinne Press I knew that I did not want to become a printer. Everything about the work was distasteful to me. I remember one job I had was to prepare a catalogue for a loan exhibition of paintings in Brooklyn. I had to go around to the offices of a lot of rich men, bankers and manufacturers, who were lending pictures, to get my information. They sometimes kept me waiting for hours and then sent out word that I would have to come again when they were not so busy. I saw that it would take years to work up in the printing business. I was entered on the payroll as an expert printer,—which I was not,—and the wages of an expert printer were then eighteen dollars a week. To give me a chance, Mr. De Vinne paid me seven dollars every Saturday night out of his own pocket. I could see no future, but, on the other hand, it seemed as if I must see the job through. In the half hour I had for my lunch, I used to go out to the City Hall Square, and look up in desperation at the sky and buildings, like a man in prison trying to find a way of escape.

I never spoke of my wretchedness to any one, but Mr. De Vinne was a kind man as well

as a great

expert, and he must have seen that I was not happy. When I had been with him for four

months, he

told me that I had better go up to the Century office and talk with Mr. Smith, intimating

that

they would be able to use me there. I had a talk with Mr. Smith and he took me on.

Thus began my

connection with the Century Company. Mr. William Ellsworth, the secretary of the company,

was

away on his vacation, and I was given some of his work to do. The work that interested

me most

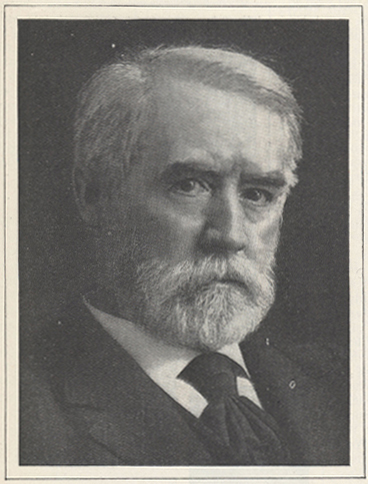

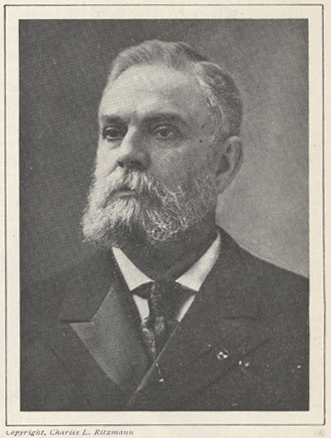

was writing announcements of the future numbers of the maga- Copyright, Charles L. Ritzmann"COLONEL POPE, while a boy in the army, had carried on his studies by the camp-fire, had made a

fortune in business within a few years after he came back from the war, and had founded

one of the greatest manufacturing concerns in Amercia"

zine. But, on the whole, I did not get on much better with my work in the Century

office than I had at De Vinne's.

Copyright, Charles L. Ritzmann"COLONEL POPE, while a boy in the army, had carried on his studies by the camp-fire, had made a

fortune in business within a few years after he came back from the war, and had founded

one of the greatest manufacturing concerns in Amercia"

zine. But, on the whole, I did not get on much better with my work in the Century

office than I had at De Vinne's.

My wife had given up her work on the Dictionary some months before, and we had moved to East Orange, New Jersey, where in July my daughter Eleanor was born. I had arranged to take my two weeks' vacation then, so that I could be with Mrs. McClure and the baby. During those two weeks, for the first time since I came to New York, I began to recover myself, to get back my mind and to have ideas. During the six months of my imprisonment in office routine I had been like another man, a wholly different creature. As soon as I got away from office work, my powers of invention seemed to return to me. One evening in East Orange, I sat down and in a few hours invented the newspaper syndicate service which I afterward put through. I saw it, in all its ramifications, as completely as I ever did afterward, and I don't think I ever added anything to my first conception.

To be sure, the thing was in the air at that time: somebody had to invent it. The New York Sun had made a tentative experiment in that direction. Mr. Dana had arranged with a number of authors, among whom were Mr. Howells, Henry James, and Bret Harte, to sell him short stories which would appear in the Sunday Sun, and on the same day would be printed in Sunday papers in Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, etc. The Boston Globe had also sold a serial in this way.

In reading over the files of St. Nicholas for the Century Company to prepare for them a "Boys' Book of Sports," I had noticed a great many articles and stories which I thought ought to be syndicated in all the country newspapers throughout the land, to supply good reading matter for the country boys and girls. I had studied the files of the Century carefully in preparing my announcements, and I knew who was writing then and what they wrote. I did not see why the Century Company should not conduct a syndicate business, selling new stories by their authors and old material from the files of St. Nicholas to newspapers. During my vacation I worked out a complete plan of such a syndicate service, covering eighteen large pages, and when I went back to work I submitted this prospectus to Mr. Frank H. Scott, afterward president of the company.

Mr. Scott gave my prospectus his friendly consideration and said he would lay it before Roswell Smith. An hour or two after Mr. Smith called me in, and said he didn't think I would ever get very far working for the Century Company; that I did not seem to be fitted to work to advantage in the offices of a big concern; that he felt the best thing for me to do would be to go out and try to found a little business of my own. My salary would be paid until the first of October, and I could have the month of September to look around. If I found nothing, Mr. Smith said, I could come back and work with them that winter. This was certainly a generous proposition.

I was fortunate in my three employers. The only men I ever worked for—Colonel Pope, Mr. De Vinne, and Roswell Smith—were all remarkable men, each a master in his own line. Colonel Pope, while a boy in the army, had carried on his studies by the camp-fire, made a fortune in business within a few years after he came back from the war, and by the time he was thirty-nine had founded one of the great manufacturing concerns in America. Mr. De Vinne was then, and is to-day, one of the world's foremost experts, a wide scholar as well as a great printer. Mr. Smith was then the preëminent magazine publisher of America. Incidentally these men had made fortunes, but they had also made great names. They were all men who could inspire a young man, who valued ideas above the price they brought in the market, and who were not ashamed to have ideals.

The more I thought about the syndicate idea, the more I believed in it. It became an obsession with me. Again I was a man of one idea, as I had been when I was determined to get an education, as I had been when I was determined to get my wife. Every one with whom I discussed the idea manifested a great indifference.

The Launching of My New Venture

If I were going to launch a new venture, I had, of course, to have a New York address. In October we moved in from East Orange and took a flat at 114 East Fifty-third Street. When we paid the month's rent in advance, twenty-three dollars, it left us almost penniless. We had four rooms, two with sun, facing on the south, and two facing on a very clean court behind the Steinway piano manufactory. We had two sleeping-rooms, a kitchen, and one otherroom which was my office as well as our sitting-room and dining-room. I got a large old-fashioned desk and put it between the two windows in that room. I went downtown and bought white paper in bulk, having it cut up into the sizes wanted for letter paper. It was months before I had any printed stationery. I had always liked the purple ink which the Century Company then used for business correspondence—this was before the general use of typewriting machines—so I laid in a supply of purple ink. Then I sat down and began to write letters to authors and editors, explaining to them my syndicate scheme.

From the authors I got immediate and enthusiastic replies. They would be delighted to be syndicated, would be delighted to write for me. But the editors were much more cool in their replies. It was then I learned that the selling end of any business is the difficult end.

My plan, briefly, was this: I could get a short story from any of the best story-writers then for $150. I figured that I ought to be able to sell that story to 100 newspapers throughout the country, at $5 each. News was syndicated in this way, and I did not see why fiction should not be.

I launched the syndicate November 16, 1884. The first thing I syndicated was a two-part story by H. H. Boyesen. I had agreed to pay Boyesen $250 for it, and although some newspapers in large cities paid as high as $20 for the right to print it, my returns on the story aggregated $50 less than the story cost me. This was a serious situation, as I was not only $50 behind, but I had no money to live on.

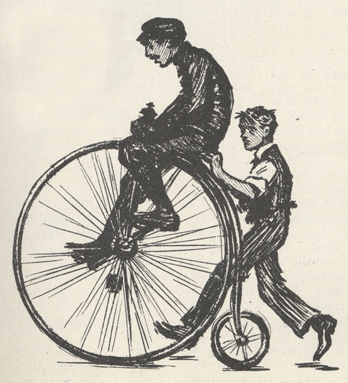

"I HAD never been on a bicycle in my life, but I was in the predicament of the dog that

had to climb a tree. In a couple of hours I had learned to ride a wheel myself and

was teaching other people"

"I HAD never been on a bicycle in my life, but I was in the predicament of the dog that

had to climb a tree. In a couple of hours I had learned to ride a wheel myself and

was teaching other people"

I went down to the Century office and borrowed $5 from a young man I had worked with there,—it must be remembered that I knew almost no one in New York,—and with this $5 I went to Philadelphia. There I sold two stories, the one by Boyesen and another by "J. S. of Dale," for $45 to Philadelphia papers. I borrowed some money from a relative there, and went on to Washington, where I also sold my stories, then home. As soon as I got back to New York, I went to Boston. There Mr. Howland, of Outing, got me a pass to Albany. Because of some limitation to my pass I had to stay overnight in North Adams, and I got the editor of the little paper there to agree to take my syndicate service of one short story a week for $1.50 a week. At Albany I sold the service for $5 a week.

When I got back to New York I found letters from several important newspapers, such as the St. Paul Pioneer Press and the San Francisco Argonaut,—which I had written to but had not heard from before,—agreeing to take the service at $8 a week. Then I realized that I was started. I paid Boyesen part of what I owed him, and lived on the rest, paying him a little more, as I could. Week after week and month after month I fell short in this way, and got deeper and deeper into debt. I got along by paying my authors $10 or $20 on account. I paid out a little less than I collected, and my actual working capital was the money I owed authors. I made no secret of this, and the men who wrote for me were usually willing to wait for their money, as they realized that my syndicate was a new source of revenue which might eventually become very profitable to them. And it did.

TO BE CONTINUED