The Red Cross Magazine

From The Red Cross Magazine, 14 (July 1919): 27-31.

ROLL CALL ON THE PRAIRIES

Illustrated by Angus MacDonallNO ONE remembers now that the "fighting spirit" of the West was ever questioned; but at the time the United States entered the war, people along the Atlantic seaboard felt concern as to how the Middle West and the prairie states would respond. Again and again I heard New York business men and journalists say that the West wouldn't know there was a war until it was in the next county: the West was too busy making money and spending it.

Myself, I scarcely realized what being "in the war" meant until I went back to Nebraska and Colorado in the summer of 1917. In New York the war was one of many subjects people talked about; but in Omaha, Lincoln, in my own town, and the other towns along the Republican Valley, and over in the north of Kansas, there was nothing but the war. Everywhere the Red Cross was fully organized and at work, the first Liberty Loan was over-subscribed, many of the young men I knew had not waited for the draft but were already in training camps. In the afternoons one saw white things gleaming in the sun off through the trees; boys in their shirts and trousers, drilling in the schoolhouse yard or in the Court House Square.

Early the next summer, when we had still to prove whether we were a fighting nation or not, the First Division, so largely made up of Western men, made our debut at Cantigny; and when the casualty lists began to appear in the New York papers, morning after morning I saw the names of little towns I knew in Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, Colorado—little country towns, happy and prosperous, where nothing so terrible or so wonderful had ever happened as to drag them into the New York newspapers, towns hidden away in miles of cornfields or tracts of sand and sage; and now their names came out one after another with the name of some boy who brought his home town into the light once and gloriously. It was like a long roll call, and all the little prairie towns were answering that they were there.

When I went West again in the summer of 1918, soon after Cantigny and Belleau Wood, I saw the working out of all that had been begun the summer before. Everyone supposed that the war would go on for another year, perhaps for two or three years, and everyone was living in the war and for the war. The women were "in the war" even more than the men. Not only in their thoughts, because they had sons and brothers in France, but in almost every detail of their daily lives.

In the first place, diet and cookery, the foundation of life, were revolutionized (city people could never realize what this means in the country and in little towns). All the neighbor women began to tell me how to make bread without white flour, cakes without eggs, cakes out of oatmeal, how to sweeten ice cream and puddings with honey or molasses. When my father absent-mindedly took a second piece of sugar at breakfast, he felt the stony eyes of his women-folk and put it back with a sigh. My old friends could talk to me all day about the number of hot breads they could make without wheat flour, about rice bread, and oatmeal loafs, and rye loafs. All winter long they had experimented with breadstuffs. In New York we merely took a new kind of bread from the baker—hoping it wouldn't be worse than the last—and grumbled at the grocer because he wouldn't give us more sugar. But in the little towns, Hooverizing was creative and a test of character as well.

Out in the big grass counties of western Nebraska, where the ranches are a long way from town and it is the custom to lay in large supplies during the summer against the chance of bad roads in winter, many of the ranchers had bought their usual amount of sugar before the injunction about saving sugar was issued. They, at least, were "well fixed," as we say, and had a liberal supply for the winter in their own store rooms. But what they did was to haul that sugar back over the long roads and deliver it to the merchants. (Again, city people wouldn't know what that meant!)

"Who is Hoover? What is he? That all our wives obey him?" I doubt if the name of mortal man was ever uttered by so many women, so many times a day, as was his. He became a moral law. Every caution and injunction he uttered was published in the little county papers in Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado—everywhere else, probably, but I know about those states—and the women no more questioned any mandate he issued than they would the revealed Word. In cities we took what was sold to us; but there the housewives had all the raw materials of their old liberal dietary, and they could be underhanded and use them if they chose. All the new cookery was more difficult and troublesome than the old, partly because it was new, and the results were not so satisfactory. When a woman had plenty of butter and eggs, when her husband's general merchandise store was stocked with flour and sugar, why should she skimp and scrape and invent to save all these?

Hoover was the answer. No wonder he got results, with every woman in every kitchen from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains watching her flour barrel and her sugar box as a cat watches its kittens. An old German farmer-woman told me, " I chust Hoovered and Hoovered so long I loss my appetite. I don't eat no more."

There wasn't a church sociable in our town all winter and spring. Late in the summer the first church supper of the year was given in the basement dining room of the Methodist Church. It was an unusually good one—lots of fried chicken with cream gravy, mashed potatoes and scalloped potatoes, half a dozen kinds of salad, white biscuit, coffee with all the sugar you wanted, ice cream, and cakes and cakes. One old lady who had "partaken" until she was quite red in the face, turned to me and said it seemed like old times to sit down to a Methodist supper once again, adding, with a twinkle in her eye, "And I don't believe he'd begrudge it to us, this once, do you?"

"He? Who?"

"Hoover."

NOT only was the cookery changed in my town and in all other little towns like it, but the whole routine of housekeeping was different from what it used to be. When a woman worked three afternoons a week at the Red Cross rooms, and knitted socks and sweaters in the evening, her domestic schedule had to be considerably altered. When I first got home I wondered why some of my old friends did not come to see me as they used to. How could they? When they were not at the Red Cross rooms, they were at home trying to catch up with their housework. One got used to such telephone messages as this:

"I will be at Surgical Dressings, in the basement of the Court House, until five. Can't you come over and walk home with me?"

That was the best one could do for a visit. The afternoon whist club had become a Red Cross sewing circle, and there were no parties but war parties. There were no town band concerts any more, because the band was in France; no football, no baseball, no skating rink. The merchants and bankers went out into the country after business hours and worked late into the night, helping the farmers, whose sons were gone, to save their grain.

Wherever I went out in the country, among the farms, the women met at least once a week at some appointed farmhouse to cut out garments, get their Red Cross instructions and materials, and then take the garments home to sew on them whenever they could. It went on in every farmhouse—American women, Swedish women, Germans, Norwegians, Bohemians, Canadian-French women, sewing and knitting. An old Danish grandmother, well along in her nineties, was knitting socks; her memory was failing and half the time she thought she was knitting for some other war, long ago. A bedridden woman who lived down by the depot begged the young girls who went canvassing to bring garments to her, so that she could work buttonholes, lying on her back. One Sunday at the Catholic church I saw an old woman crippled with rheumatism and palsy who had not risen during the service for years. But when the choir sang "The Star Spangled Banner" at the close of the mass she got to her feet and, using the shoulder of her little grandson for a crutch, stood, her head trembling and wobbling, until the last note died away.

FROM memory I cannot say how many hundreds of sweaters, drawers, bed jackets, women's blouses, mufflers, socks came out of our county. Before the day of shipment they were all brought to town and piled up in the show-windows of the shoe store—more than any one could believe, and next month there would be just as many. I used to walk slowly by, looking at them. Their presence there was taken as a matter of course, and I didn't wish to seem eccentric. Bales of heavy, queer-shaped chemises and blouses made for the homeless women of northern France, by the women on these big, safe, prosperous farms where there was plenty of everything but sons. When a people really speaks to a people, I felt, it doesn't speak by oratory or cablegrams; it speaks by things like these.

Up in the French settlement, in the north part of our county, the boys had been snatched away early—not to training camps or to way-stations, but rushed through to France. They all spoke a little household French, which was just what the American college boy who had been reading Racine and Victor Hugo could not do. So our French boys were given a few weeks of instruction and scattered among the American Expeditionary Force at the front wherever they were most needed

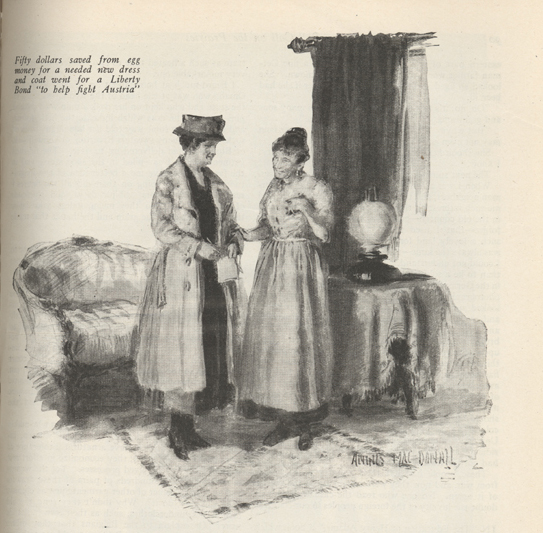

Sarka Herbkova, Professor of Slavonic Languages at the University of Nebraska, did invaluable work in organizing not only the women of her own people, but all the women of Nebraska, American born and foreign born. She went about over the state a great deal for the Women's Council for National Defense and saw what sacrifices some of the farmers' wives made. She told a story of a Bohemian woman, living in one of the far western counties, who had saved fifty dollars of her egg money to buy a new winter dress and a warm coat. A Liberty Bond canvasser rode up to her door and presented her arguments. She heard the canvasser through, then brought her fifty dollars and put it down on the table and took the bond, remarking, "I guess I help fight Austria in my same clothes anyhow!"

Letters from the front usually reached our town on Saturday nights. The "foreign mail"

had become a feature of life in Kansas and Nebraska. The letters came in bunches;

if one mother heard from her son, so did half a dozen others. One could hear them

chatting to each other about what Vernon thought of Bordeaux, or what Roy had to say

about the farming country along the Oise, or how much Elmer had enjoyed his rest leave

in Paris. To me, knowing the boys, nearly all of these letters were remarkable. The

most amusing were those which made severe strictures upon American manners; the boys

were afraid the French would think us all farmers! One complained that his comrades

Fifty dollars saved from egg money for a needed new dress and coat went for a Liberty

Bond "to help fight Austria"

talked and pushed chairs about in the Y hut while the singers who came to entertain

them were on the platform. "And in this country, too, the Home of Politeness! Some

yaps have no pride," he wrote bitterly. I can say for the boys from our town that

they wanted to make a good impression.

Fifty dollars saved from egg money for a needed new dress and coat went for a Liberty

Bond "to help fight Austria"

talked and pushed chairs about in the Y hut while the singers who came to entertain

them were on the platform. "And in this country, too, the Home of Politeness! Some

yaps have no pride," he wrote bitterly. I can say for the boys from our town that

they wanted to make a good impression.

A serious young man who had just come out of severe action wrote that he thought the Lord must have spared him for a purpose; but he was later killed in one of the advances before Château-Thiérry. A lively boy, the town favorite, who was dying of his wounds in a hospital on the Place de la Concorde, wrote only gay letters, telling about the charm of Paris, the kindness of everyone, and the pretty French girls who came to hold his hand and talk to him while his dressings were being changed. One happy-go-lucky lad, a third generation German, wrote often and was always having the time of his life; he had been buying laces for his mother in Paris, or recuperating in villas at Nice and Aix-les Bains. He was coming home to Red Cloud all right, but he was coming by way of Vienna and Berlin. The butcher's son happened to be in London, and his letters were a curious mixture of information about Zeppelin raids and London monuments, and his burning curiosity to know more about the electric meat-chopper that had been put in the shop at home since he went away.

While I was at home the fourth Lovemann boy was drafted—his three brothers were already at the front. The father was a farmer, and a farmer's sons are his arms and hands; he can't work the land without them. The oldest son wrote in mournful anxiety from Paris, "If John goes, who will get the corn in this fall?" It seemed to me unfair that all the Lovemann boys should have to go. I asked a German girl, a neighbor of the Lovemanns', why they didn't try to get exemption for John. "His sister says if they got exemption, John would run away!" she declared proudly.

Early in the summer of 1917, I stopped in the eastern part of the state and went to see a fine German farmer woman whom I had always known. She looked so aged and broken that I asked her if she had been ill.

"Oh, no; it's this terrible war. I have so many sons and grandsons. I am making black dresses."

"But why? The draft is not called yet. Your men may not even go. Why get ready to bury them?"

She shook her head. "I come from a war country. I know."

The next summer she was wearing her black dresses.

When I was a child, on the farm, we had many German neighbors, and the mothers and grandmothers told me such interesting things about farm-life and customs in the old country—beautiful things which I can never forget—that I used to ask them why they had left such a lovely land for our raw prairies. The answer was always the same—to escape military service. That I could not understand. What could be more romantic than to be a soldier? Some of our farmers had served in the German Army in their youth, and their wives had photographs of them in their uniforms; certainly they looked more jaunty and attractive than in their shirts and overalls as I saw them every day. The women, and even the children, used to tell me stories of the brutality of officers; how their father had been spat upon and struck in the face, and made to do repulsive things. Out in Wyoming I knew a clergyman who had been an officer in the German Army and had run away while he wore the uniform, escaping from the port of Antwerp after almost incredible dangers. He was a mild, genial man, and I could not understand why he should have run such chances. He explained that his colonel, a stupid and disgusting young count who hated University men, had selected him as the butt of his ridicule, and had so abused and humiliated him that he had not the least fear of death.

These people had left their country to get away from war, and now they were caught up in the wheels of it again. No one who read the casualty lists can doubt the loyalty of the foreign peoples in our country.

IN "The Education of Henry Adams," a book which everyone has been reading, Mr. Adams says, in speaking of his student life in Germany: "I loved, or thought I loved, the people, but the Germany I loved was the eighteenth-century which the Germans were ashamed of, and were destroying as fast as they could." Our Germans in the West are nearly all people of that old-fashioned type who came away because they could not bear conditions at home. Two rich German farmers who lived on their broad acres near Beatrice, Nebraska, did say bitter things when America entered the war. They were summoned before a magistrate in Lincoln, who fined them lightly and administered to them a rebuke which was so wise and temperate and fair-minded that I cut the printed report of it out of the newspaper and put it in my scrap-book. "No man," he said, "can ask you to cease from loving the country of your birth." Sentences are commonplace or memorable according to the circumstances in which they are spoken; I thought that sentence, uttered by a magistrate at such a heated time to two blustery old men, a very remarkable one.

I heard much at home about an efficient woman in Omaha who was at the head of the Red Cross work in the state and who kept on her desk a map with colored pins stuck in the dots which indicate the little towns, and these pins in some way told her how many pairs of socks and how many sweaters Riverton, or Guide Rock, or Blue Hill, had delivered up to date. The finished garments which I saw piled in the shoe store, and in the farm houses, gave me a better idea of the magnitude of what was going on than did all the figures I read in the newspapers. Shiploads of food, shiploads of clothes—what do they mean, unless you know the fields that grew the grain and the hands that made the clothes?

NOTHING brought the wonders of this war home to me so much as the work I saw being done on what were called "refugee garments"—chemises and blouses for the destitute women of Belgium and northern France, and underdrawers and shirts for the old men. These garments were all made according to very minute instructions from Headquarters, and they were exactly like the clothes these people had been accustomed to wear. Anything more clumsy and out-of-date according to American standards could hardly be imagined. In the Red Cross rooms under the court house and in the basement of the town library, out in the farmhouses all over our great rich county, women sat day after day and made underdrawers with from ten to fifteen buttons, and worked the buttonholes.

I am sure there is not a woman in our town who makes her husband's underclothes. American women, especially Western women, have a natural intolerance of slow, old-fashioned ways; they economize in effort and in time, eliminate involved processes. Yet the women in our town made hundreds of pairs of these drawers and an equal number of other garments just as clumsy. Why did they do it? Why didn't they send the old men X.Y.Z. underclothes, such as their own husbands wore? Or explain to the Belgians that they didn't need buttonholes, and that Belgium would get on better if she adopted modern methods? Americans are never slow to give advice of that kind.

I believe, in this case, the answer is that our women simply admired Belgium too much; they had no suggestions to offer to such a people. Their one wish was that those old men and women should have the kind of clothes they had always lived in, with no feeling of strangeness. The every-day ways of a very foreign people had come through to us, who are always so sure that our own are best. A great deal of verse has been written to Belgium in this country; but when I saw our smart, capable Western women patiently making drawers with fifteen buttonholes and smiling with a kind of pride in their work, I thought that was poetry. I knew how many old feelings must have been rooted out and new feelings born, to make them want to do it, love to do it, in that tedious way that was against the tempo of their whole lives.

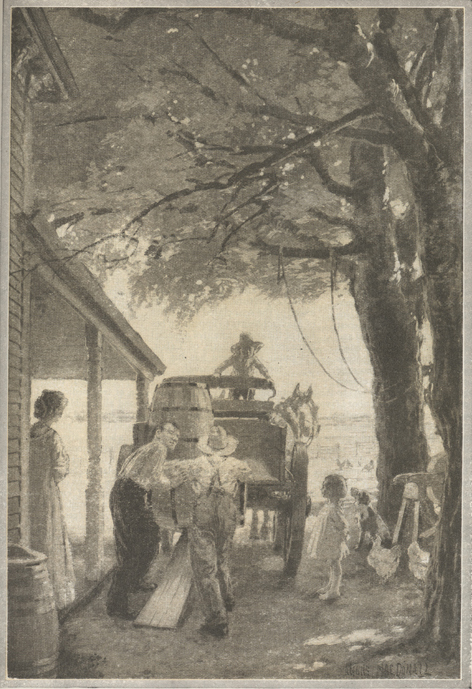

In western Nebraska, many ranchers had bought enough sugar for winter before they

knew of the injunction against saving it. When they did learn of it, they hauled the

sugar back over many miles to the merchants

In western Nebraska, many ranchers had bought enough sugar for winter before they

knew of the injunction against saving it. When they did learn of it, they hauled the

sugar back over many miles to the merchants