The Home Monthly

From The Home Monthly, 6 (June 1897): 1-4.

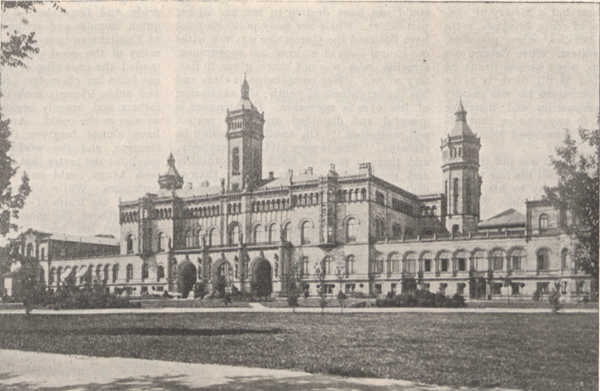

WINDSOR PALACE, THE HOME OF THE HANOVERIAN KINGS IN ENGLAND.

WINDSOR PALACE, THE HOME OF THE HANOVERIAN KINGS IN ENGLAND.

Victoria's Ancestors: The House of Hanover.

SIXTY years ago, when the young Queen sat in her coronation robes upon the throne in Westminster Abbey, and the golden orb was handed her, she whispered to Sir John Thynne, "What am I to do with it?"

"Your Majesty is to carry it, if you please, in your hand."

"Am I?" she sighed ; "it is very heavy."

Yet she has carried it longer than any sovereign in all the history of England. The young Queen might well complain at the heaviness of the burden, heavy enough at any time, and weighted then with all the mistakes of her house, with all the sins and blunders of that blundering house of Hanover. Englishmen may very honestly congratulate themselves upon Victoria's long reign, for her's has been the only creditable one since the taciturn George I came over to England with his German cooks and German countesses and was crowned at Westminster. Her name will be remembered in history not because of her brilliancy or cleverness, for she has neither, but because she had so much to live down and has lived it down so well, because she has almost made the world forget the history of her house and that she, too, came out of Herrenhausen. Indeed, without recalling something of the lives and misrule of the Hanoverian kings, it is almost impossible to appreciate what Victoria's reign has meant to England.

When Elizabeth, the daughter of James I, married the Elector Palatine she little thought that her alliance would bring the downfall of her house and eventually place a line of foreign kings upon the throne of the Stuarts. When all her sons died, leaving only one daughter surviving, such an event seemed more improbable than ever. But this daughter was no ordinary maid. She was, indeed, much more promising than any of Elizabeth's sons, and even before she married the Great Elector of Hanover, Sophia's eyes were fixed meaningly upon England. With Sophia the reign of the House of Hanover properly began, although she never lived to wear the English crown, nor was her fondest hope ever realized, that of having written upon her tomb, "Here lies Sophia, Queen of England." But without her innumerable schemes and resources it is not likely that George Louis, her stupid and phlegmatic son, would have ever made his triumphant entry into London.

When, on the 30th of July, 1714, Queen Anne, old and childless, wrecked Boling- broke's fine plans and died from a stroke of apoplexy, the Privy Council could only look to Hanover for her successor, and the English crown fell to George Louis, the great-grandson of James I, who at once became George I of England, though he was so little of an Englishman that until the day he died he could never speak the language of the people he governed. His crafty old mother, the Electress Sophia, had all her life planned and schemed and plotted to establish the Hanover line on the English throne; through herself if possible, if not, through her son, whom she loved just as little as did the rest of the world. But, as the Anglo-Saxon chronicler has it, "None of a truth can tell the ways of Fate," and she died on the very eve of the accomplishment of the hopes of a lifetime. Only three months before George I was proclaimed King of England she received a malignant letter from Queen Anne, whose one foot was already in the grave, and fell into such a rage that she grew ill. Two days after reading it she fell in a swoon while walking in the gardens at Herrenhausen and died, and her hatred with her. Ah, how those Queens could hate! It has been said that for the last few years of her wretched old life the Electress lived upon her hatred as an invalid does upon stimulants, but it killed her at last. And Anne, as though she could not outlive the animosity which was the bitter comfort of her bitter age, died too, and the world was just that much better off.

So it was that George Louis, already beyond his fiftieth year, and worn and wasted by the worst kind of life a man can live, left Hanover on the Lein, left the land where, in the castle of Ahlden, he kept his wife, Sophia Dorothea, who, alas ! was not so much better than her husband, shut up a prisoner for thirty-two years, and came at last into his kingdom; a kingdom that only accepted him in lieu of anything better, and which he despised so heartily that for the rest of his life he saw as little of it as possible. But it can at least be said of him that he troubled England very little. Like his son after him he was always going to Hanover, taking with him all the money and jewels and plunder of any sort he could lay hands on. But if he plundered the English treasury he at least never laid violent hands on English liberty, that was growing steadily, quietly, as it continued to do all through the rule of the stolid Hanoverian monarchs until it grew strong enough to crush a hundred kings.

So George Louis stayed at Windsor as little as possible, always sighing for his beloved Deutchland, and when he was there converted it into a sort of Deutchland, with his drinking and gambling and coarse jokes, his low Hanover buffoons and his painted Hanover ladies. There, in the middle of England, on the English throne itself, he planted a little Dutch empire. And the English people never minded at all, but laughed and went their way. After the dashing gallantry of the Stuarts they found the crudeness of these peasants who quarrelled with each other about money bags and warred about windmills amusing. But the joke grew old, as jokes will, and before they were through with these Black Foresters Englishmen laughed on the other side of their faces. The Stuarts were not model men by any means, but they were kings, every one of them, and bore themselves right royally. Their heads were light, but so were their hearts, and if they did foolish things they said graceful ones. They shone alike on the field or at the banquet hoard, and men loved them almost as fondly and faithfully as women did, which is saying a great deal. Their very vices were more tolerable than the spiritless virtues of the Hanoverians.

But all things have an end, even the reigns of kings, and finally, only a little after

his Queen had died in her prison at Ahlden, freed after thirty-two years by that liberator

who opens the prisons of every one of us at last, on one of his innumerable journeys

back to Herrenhausen, this Dutchman whom capricious fortune had made

QUEEN VICTORIA

AT TWENTY-ONE.

King of England, set out, all unwilling, upon a longer journey than that to Hanover.

He died very much as he had lived: brutal, taciturn, unloving and unloved—unless those

two rapacious Countesses who had followed him to England, and whom the jeering populace

had named the "Elephant" and the "May Pole," could be said to have loved him.

QUEEN VICTORIA

AT TWENTY-ONE.

King of England, set out, all unwilling, upon a longer journey than that to Hanover.

He died very much as he had lived: brutal, taciturn, unloving and unloved—unless those

two rapacious Countesses who had followed him to England, and whom the jeering populace

had named the "Elephant" and the "May Pole," could be said to have loved him.

George II was very unlike his royal father, save that he was quite as little of an Englishman and quite as little of a king. He cut rather a better figure at court than the first George, and no figure at all in politics. His official acts, words, thoughts were dictated to him by his wife, who in turn was dictated to by Walpole. As a young man George had been little better than a common pot-house rowdy—perhaps a little worse. As a King his tastes did not improve. Cockfighting, gaming, brandy and the robust beauties of Hanover were the only things he deemed worthy of serious consideration. Of education he had little, and he never learned to speak English with ease, although he was for three-and-thirty years King of England. He had no taste for art of any sort, and, though he used sometimes to quote poetry in his voluminous letters to the Countess Walmoden, he despised both literature and music. The first great English painter lived and wrought in his time, but George never even knew it. When he heard that Hogarth had drawn a caricature of one of his officers he flew into a towering passion and cried: "Zounds, a dog of a painter insult a soldier!" There was only one thing that George really respected and that was valor. He had been a good soldier himself. He was a man indeed on the field of Oudenarde, for the only time in all his boisterous, brawling life. Like all his house he was brave. Those ugly fellows from Hanover were at least not afraid of death, though they bungled at life so sadly. The second George bungled like all the rest. He was not happy for all his low sports and countless indulgences. No man ever pursued pleasure more assiduously, no man ever missed it so utterly. He was unhappy in his kingdom, unhappy in his parentage, unhappy in his children—in short, in everything but in his Queen. Brutal and unlovable as he was, he was blessed with the infatuate affection of one of the most devoted women in history. Caroline thought, felt, lived for him alone, and in the end she died for him. She neglected herself and her own children for him. All her being was spent in the great and constant love she gave him. To others she was only a sordid, selfish woman; a dangerous enemy, a still more dangerous friend. But to George she was all the virtues. She gave him all the good that Heaven had given her and had nothing but coldness and craft left for others. She died, Lord Hervey tells us, from concealing her malady from her royal husband lest it should annoy him, and from plunging her gouty feet in cold water that she might stroll with him when it suited his royal pleasure. She could indeed say with poor Catherine of Aragon that she had "almost forgot her prayers to content him." On her death bed she made a languid effort to patch up her peace with Heaven, but her last words were not to God but to George, begging him to let her death cast no shadow over his pleasures, but to live on merrily while he might. As though any one needed to enjoin that upon George!

Of Frederick, George's eldest son, the Prince so fondly beloved in his boyhood, later

so bitterly hated, little is known save that he made his wife, his mother and his

children equally wretched, that his father cursed him all his profligate life, and

his own son was ashamed to speak his name. I have beside me an edition of Ovid by

Mr. Nathan Bailey, sometime scholar and linguist, affectionately dedicated in florid

Latin phrases to "that most brilliant and illustrious Prince, Frederick, Prince of

Wales, with many prayers and wishes that the Most High God may preserve you in all

felicity and safety to your people of

THE ROYAL PALACE AT HANOVER.

Britain." I have my doubts as to how much of his princely leisure Frederick ever wasted

in construing Ovid, but at any rate he was once a happy little boy whom his people

loved, little thinking how they would one day rejoice that he was dead and could bring

disgrace upon them no more. The brutal epitaph that some wag wrote on him was repeated

approvingly

THE ROYAL PALACE AT HANOVER.

Britain." I have my doubts as to how much of his princely leisure Frederick ever wasted

in construing Ovid, but at any rate he was once a happy little boy whom his people

loved, little thinking how they would one day rejoice that he was dead and could bring

disgrace upon them no more. The brutal epitaph that some wag wrote on him was repeated

approvingly

GEORGE I WHO ESTABLISHED

THE HANOVERIAN LINE

IN ENGLAND.

through the length and breadth of the kingdom, and, though it deals bluntly enough

with Frederick, it refers to his family with equal candor and shows very clearly how

these Hanover folks were regarded by their adoring subjects.

"Here lies Fred,

Who was alive, and is dead.

Had it been his father,

I had much rather,

Had it been his brother,

Still better than another.

Had it been his sister,

No one would have missed her.

Had it been the whole generation,

Still better for the nation

But since 'tis only Fred,

Who was alive, and is dead,

There's no more to be said."

GEORGE I WHO ESTABLISHED

THE HANOVERIAN LINE

IN ENGLAND.

through the length and breadth of the kingdom, and, though it deals bluntly enough

with Frederick, it refers to his family with equal candor and shows very clearly how

these Hanover folks were regarded by their adoring subjects.

"Here lies Fred,

Who was alive, and is dead.

Had it been his father,

I had much rather,

Had it been his brother,

Still better than another.

Had it been his sister,

No one would have missed her.

Had it been the whole generation,

Still better for the nation

But since 'tis only Fred,

Who was alive, and is dead,

There's no more to be said."

In 1760 the people of England, by this time grown sneeringly accustomed to foreign mastership, hailed George III, grandson of George II, as King, Defender of the Faith, etc. And though so much better as a man, he made the worst King of the lot—just because, indeed, he tried to be a better one. The Hanover men were not cast in the mould of Kings, and they were better when they did not try to play at sovereignty but contented themselves with their German drinks and German cookery and German favorites. If George had been a great man, well and good. But he was no greater than his grandfather or great-grandfather before him, and he found himself pitted against a power that was truly great, that of the English people. Nature had been even more niggardly with him than with his ancestors. His natural abilities were of the meanest order and his education had been sadly neglected. All through his starved, unhappy childhood his harsh old mother had continually dinned in his ears, "George, be a King!" and a King he tried to be. He would be advised by no man. He hated all the great men of his time because he wished alone to be great. He hated Pitt and Walpole, he hated Pelham and Burke. His treatment of them was ungenerous, petty, spiteful. He plunged England into a chaos of civil and political strife, he drove the American Colonies to war and lost them. Yet for all his obdurate stupidity he was a good man; sincerely pious, genuinely affectionate. But the sins of his ancestors were heavily upon him, and he paid for them, even to his insanity, which was the inevitable sequel of such misspent lives. One can almost forgive him his errors as one pictures him, a white-haired old man, blind, stone deaf, deprived both of the light of Heaven and the light of reason, wandering about his palace, calling pitifully upon the names of his sons who had grown to hate and despise him, muttering tenderly of the dear, dead Amelia whose death had quenched the last spark of reason in that dull brain.

Great events shaped themselves in George's reign, and great victories were won for England; the battle of the Nile was fought, and at Waterloo the sun of Bonaparte set forever. But these were the triumphs of the great English people,. whose power had grown, like the tree in Gautier's poem, until it shattered the vase in which it was planted. The great forces of modern England were upon the world, and the world had almost forgot the demented old man who bore still the name of King.

From the tragic portrait of this Lear we pass to that of an Osric, a fop with curled

hair and perfumed fingers. The first three Georges were ungainly figures enough, clumsy

stone images like the statues in their own gardens at Herrenhausen, but now we come

to a King of papier maché, whose serious moments were spent with his cosmetics and his hairdresser. Even so

the succession went in old Rome; power, dissipation, insanity, then effeminacy. It

was the old poison of the Purple, the old madness of Empire. The most gossiping historians

have found little of interest to say of George IV, even of his vices. He was a hero

to his valet and to no one else. A biography of him would read like a

QUEEN VICTORIA

AND

THE PRINCE CONSORT.

tailor's order book or a butler's wine list. It would be at best but a history of

costumes, a catalogue of coats, breeches, satin waistcoats, shoe buckles, wigs, pomades,

cosmetics, toilet waters. When George was sober he was a fop, when he was drunk he

was a ruffian. That is all there is to be said. On great occasions he was usually

drunk, at his coronation and marriage notably so. Was it any wonder that his wife

did badly and astonished Europe by her eccentricities?

QUEEN VICTORIA

AND

THE PRINCE CONSORT.

tailor's order book or a butler's wine list. It would be at best but a history of

costumes, a catalogue of coats, breeches, satin waistcoats, shoe buckles, wigs, pomades,

cosmetics, toilet waters. When George was sober he was a fop, when he was drunk he

was a ruffian. That is all there is to be said. On great occasions he was usually

drunk, at his coronation and marriage notably so. Was it any wonder that his wife

did badly and astonished Europe by her eccentricities?

George died at last and was put into his grave clothes, the last of all his fine toilets, and was mourned sincerely by his tailor. He was succeeded by his brother, William IV. William, an old man when he was called to the throne, had lived a plain, peaceable existence and had he never been King no one would have had an evil word to say of him. But the crown had even in his case its usual intoxicating effect. The unpretentious William was carried quite beyond himself by this sudden acquisition of power. He indulged in a thousand extravagances and absurdities and was mentally unsettled to such a degree that his own people believed him insane. He was forever falling out with his own relatives, and quarreled in a most disgraceful manner with the Duchess of Kent, the Princess Victoria's mother. For the young Princess herself he felt a genuine affection, but one scene from these royal quarrels as related by Greville will show in what trying positions the enmity between her mother and the King often placed Victoria. The King had invited the Princess and her mother to be present at the celebration of the Queen's birthday at Windsor, August 13th, and to remain until his own birthday, which came on the 20th of the same month. The haughty Duchess replied that she could not attend the celebration of the Queen's birthday, as she had one of her own to celebrate on the 15th, but that she would be at Windsor on the 20th. This made the King angry enough, but for once he held his peace. When he returned to Windsor from Parliament on the 20th, he discovered that the Duchess had appropriated for her own use a suite of apartments which he had refused her the year before and had expressly stated he did not wish her to occupy. This put the King in a fury. Upon entering the drawing-room where the birthday party was assembled he greeted the Princess warmly, taking both her hands, and merely bowed to her mother. At dinner, after his health was drunk, he broke into a fierce tirade against the Duchess, outraging every law of hospitality and insulting a guest who sat at his table, at his very side. He expressed his desire to live until the Princess became of age, as he did not wish to leave her subjected to the evil influence of her mother, by whom, he declared, he had been grossly and continually insulted. The poor young Princess burst into tears and a terrible scene ensued between the King and the Duchess, which ended by that lady ordering her carriage and declaring that she would not spend another moment under his roof.

William was gratified in his wish that he might live until the Princess became of age, though he lived very little longer. His last illness was already upon him when she celebrated her eighteenth birthday. June 20th he died, and on the same morning the Queen for the first time met her Council. The impression she made on this occasion will be long remembered in England. Her youth, her frankness, her modesty were all in her favor, and her councilors were convinced that at last something good had come out of Herrenhausen. The old Duke of Wellington said that had she been his own daughter he could not have desired to see her fill her part better. While her early portraits must have flattered the Queen, she was not without charm both of manner and appearance. Greville, who was not much given to flattery wrote: "Her complexion is clear and has the brightness of youth; the expression of her eyes is agreeable. Her manner is graceful and dignified and with perfect self-possession." On another occasion he remarks : "She is very civil to everybody, and there is more of frankness, cordiality and good humor in her manner than of dignity. She looks and speaks cheerfully. There is nothing to criticize, nothing particularly to admire."

At her coronation she strengthened the good impression she made on the occasion of her first meeting with her Council. Well might she call the orb heavy, for it had crushed the heart of more than one English Queen, and the brows beneath it had grown gray before their time. When old Lord Rolle, who was well on to ninety, stumbled and fell as he was mounting the steps of the throne, she rose quickly and went down two steps to meet him and prevented his coming further. After so many years of pride and insolence on the throne, that quick impulse and action made the hearts of Englishmen beat glad. And, unlike so many of the good omens which have attended the crowning of sovereigns, it did not belie her character. Simply, modestly and nobly Victoria took the throne of her fathers and bravely began to right their wrongs as she could. And for her sake we have almost forgiven the reigns of the Georges, and the world has changed so much for the better that it seems as though such kings could only have lived in the dark ages. While Victoria is not wholly without the traits of her house, she is at least without the most objectionable. If her court has been dull, it has at least never been corrupt. If she has never been brilliant, she has never been anything but exemplary in her life. In artistic sense she is quite as lacking as her grandfathers, but it is better for England that she should paint bad pictures, approve of Alfred Austin and even delight in Marie Corelli, than that in other and weightier matters she should resemble her illustrious Hanoverian ancestors.