The Red Cross Magazine

by Willa Sibert Cather

From The Red Cross Magazine, 14 (October 1919): 54-55, 68-70.

There was no bell, but every morning at the same hour the children came hurrying on

foot or creeping along three deep on a horse

There was no bell, but every morning at the same hour the children came hurrying on

foot or creeping along three deep on a horse

THE EDUCATION YOU HAVE TO FIGHT FOR

A personal sketch of the Prairie School House

which grew into the great State University

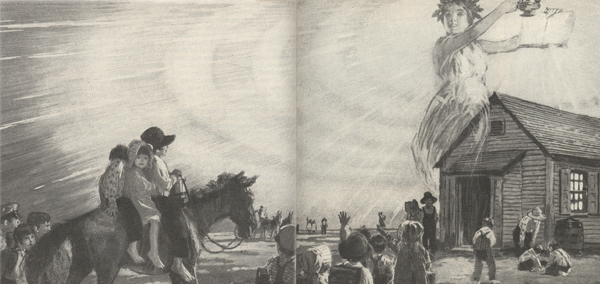

Illustration by Angus MacDonall

THE prairie schoolhouse was there before the buffalo had gone. In its first form it was made from the prairie, built of tough layers of the original sod that had never been pierced by a plow-share. The pioneers did not wait until they were making a living to begin to think about schools. In Kansas and Nebraska almost every community had a "frame" schoolhouse, while the settlers themselves were still living in sod houses and dugouts. Before there were any churches the building that was a schoolhouse all week became a church on Sunday and the congregation sat on the low seats behind the inkwells. The schoolhouses were used for political meetings and voting places, for funerals and Sunday school entertainments. They were the centers of community life from the time there was any community life at all.

Teaching was not a profession then; it was a kind of missionary work, a solemn duty, like caring for the sick. In every district there was sure to be at least one farmer's wife who had taught before her marriage, and she was called upon to take charge of the school for the short winter and spring terms. If she had young children she bundled them into the lumber wagon and took them to school with her every day. The teachers were not always women; sometimes a homesteader taught during the winter months when there was not much to be done on his land.

I remember one farmer schoolmaster who used to get up early in the morning, drive about the neighborhood collecting his pupils in his wagon and haul them to the schoolhouse. If the weather was bad he took them home again at night. He was then a mature-looking man, with a bushy beard, and he had children of his own. He used to tell his "scholars" that the thing he had most wanted was a college education, and that he had not yet given up hope of getting it. As his family grew he stopped teaching and devoted himself to his land. Twenty years went by. He developed two farms, brought up his children and married them off. Then he amazed his neighbors by quietly going away to study at a college in a distant State. A farmer cannot do so unusual a thing as that without causing a wagging of heads in a country community, and it was surprising, even to the summer visitor, who asked about the health of an old settler, to be told that he was "away at college." It takes courage, of course, to do what one wants to in this world, and the smaller the community the harder it is to defy public opinion. But our old neighbor did just that. He went to college, and stayed until he got his degree.

One hot summer day I was driving across the country with a clumsy livery plug when I noticed an open buckboard with two horses approaching rapidly from the opposite direction. As the cart came nearer I saw a man in white flannel clothes and a Panama hat, who sat holding on his knees something that looked like a large picture in a flashing gilt frame. The brisk team was driven by a girl who sat at his right. They passed me at a quick trot, but in that moment I recognized the bushy white beard and blue eyes of the pioneer school teacher, just returning home from college. On his knee he carried his diploma, which had that morning been framed in town. I hope he felt as much pleased at his triumph as I did.

The country schoolhouses were lonely looking buildings, nearly always rectangular, three windows on each side, with a little entry-hall and a door at one end. They sat out on the bare prairie, without a bush or tree or fence. A gray spot, where the grass was worn short, indicated the playground. There was no bell, but every morning at the same hour the children came hurrying on foot or creeping along three-deep on a horse that was too old to work; and in the afternoon they ran away, flashing their empty dinner pails in the sun. They were rather reserved children, bashful and uncommunicative even with each other, too frightened to make a sound when the county superintendent came to inspect their school. They saw very few strangers, and the farms were too far apart for children to visit each other often. The very little ones were so shy that their first days at school were a dreaded ordeal and sometimes they cried bitterly. Their clothes were much clumsier than those that country children wear today. The girls wore severe gingham aprons, buttoned up the back, and sunbonnets, and the boys usually had to appear in their father's clothes, cut down by a mother who was too busy to become an expert tailoress. The boys grew more lively and seemed more at ease when warm weather came and they could run free in two garments, a shirt and blue overalls. Summer brought lazy, pleasant days in the schoolroom and interesting distractions for the noon hour, such as drowning out gophers and bullsnakes, and discussing what was the best thing to do if a rattler bit you.

The children were always trying to find wild flowers that would puzzle the teacher. That was not hard to do, for the old, unrevised Gray's Botany, which was the text-book then, though it was supposed to cover all the flora to the 100th meridian, touched the flowers of western Nebraska and Kansas very lightly, and the gorgeous flora of the Rocky Mountains was largely unnamed and undiscovered. We were living in a world of mysterious flowers that had never been put into books, and the best we could do was to hitch them up with some family to which they apparently belonged and invent names of our own for them.

During my own schooldays a young Swede came over from Stockholm to study under Dr.

Charles E. Bessey, the botanist at the University of Nebraska, and he and some of

his fellow students used to go on camping trips in Colorado and Wyoming during the

summer vacations. They reported and named hundreds of flowers that had never been

noticed before. Every thing was so new in those days that a party of students—all

(Continued on Page 68)

THE EDUCATION YOU HAVE TO FIGHT FOR

(Continued from Page 55)

very exceptional young men, to be sure—could actually strike off into the hills with

a pack-mule and a tent and christen the flowers of their country.

In writing about the prairie schoolhouse one keeps getting away from it; and that is just what the pupils and the teachers did. It was a way station, where one took the train for something bigger.

After the days when the farmers and farmers' wives took turns keeping school, our country teachers were usually very young people, high school graduates, who were trying to make enough money to go away to college or to prepare for some profession. Perhaps they did not have all the qualifications of trained teachers, but they had an energy and enthusiasm that was very effective in stirring up country children. To my mind a teacher is never the worse for having personal ambitions; anything that gives him direction and intensity is all to the good of his pupils. In the West we have many men of affairs, doctors and lawyers, bankers and railroad officials, who spent a few of the most vigorous years of their youth teaching school. The best teachers I ever had were those who were on their way to something else. Their momentum carried us on a little way.

I remember one young teacher who used to spend the noon hour with his elbows on his desk and his head bent over a Latin book. From the arrangement of the lines on the page we knew that it was poetry. His face was sometimes very stern while he read, and be would compress his lips and fly at his lexicon in a way that made us feel that what he read must be very exciting. I used to long to know what it was about, but I never got up courage to ask him. The mere sight of that boy at his desk was worth as much as anything that can be taught in courses in pedagogy. Children can't be fooled; they know when learning is priceless to a man and when he is merely making his living out of it.

To many young men and women in those new States learning was priceless. The country was full of boys walking up and down the long corn rows on the farms, or sweeping out the grocery store in the little towns, who were night and day planning and contriving how they could go to college. Because it was so difficult then, it seemed infinitely desirable.

The case of Dr. Samuel Williston, Professor of Paleontology at the University of Chicago, who died last summer, is very typical. When he was a baby his parents left Boston and went West, traveling overland in a prairie schooner. They took up a homestead near Manhattan, Kan., on a grant of land made by President Lincoln. When Samuel was sixteen years old his father sent him to the Kansas Agricultural School. But young Williston did not want to be a farmer. He wanted to become a scholar of some kind, though he had no notion how to set about it, and he wanted to see the world. He ran away from school, joined a construction gang, and for three years worked as a railroad hand, surveying and grading the first line from Kansas down into Arkansas. While he was working in gravel beds and cutting down chalk hills full of fossils he found that he wanted to be a scientist. At nineteen he went back to the school he had left, finished his course, and afterward worked his way to Yale. During his life Dr. Williston wrote a great many scientific books of the highest importance and at his death he left a collection of flies and fossil reptiles which contained over a million specimens which had not previously been identified, and discovered the oldest known reptile in the carboniferous period, a monster with three eyes. The universities of Russia, Germany, France and England repeatedly sent representatives to study with him and to work with his wonderful collection.

The prairie schoolhouse often started boys off on careers like this. Other countries have had their peasant scholars, but they were so rare that they became proverbial, while in our country they are so usual that they are not even commented upon.

Twenty-five years ago the Western farmers were poor; forty years ago they were poorer still. The newly founded State universities were poor, and so were the professors. There were no scholarships. The difficulties that lay between a country boy and a college education were unsurmountable except to fellows with unusual pluck and endurance.

When the University of Nebraska consisted of one red building on a buffalo-grass campus, three farmer boys came up one autumn to go to school. They had almost no money, but each brought certain supplies from home; one brought potatoes and root vegetables, another home-cured hams, another plenty of sorghum molasses. They had not known each other before they came to Lincoln, but their ambitions and their necessities were alike, and they soon became friends. They rented a little house on the outskirts of the town, pooled their provisions and "batched" together. They tended furnaces, worked in the printing office, took care of office buildings, got work enough to meet their expenses and give them a little spending money. They must have "ground," of course, but they were not grinds. The record they left behind them for mischief was almost as often quoted afterwards as that they left for scholarship. They worked their way through the four years of the course, and then went abroad to study. Years later, when I went to school at that university, these three men were all professors in older and larger institutions, and their names were held out to encourage freshmen who had a hard road before them. Yet these three men were not markedly exceptional, except, perhaps, in their success.

Though conditions had become a little easier when I was a student at the university, one never knew what a hard time one's classmates might be having. I remember we had a grown man in our freshman class who was very popular in spite of the fact that his mustache made him seem a little awkward in class where some of the boys wore knee trousers. He was always jolly, and nobody suspected what a hard fight he had made to come to school. One spring afternoon he came up to me on the campus and said he wanted to bid me goodbye. His father was very ill and he was going home to take charge of the farm.

"It's the third time I've tried to come to school and been pulled back," he said, "but I won't give up. I think I'll be here to read the Odyssey with the rest of you next year. I'm going to keep up my Greek at home."

His father died, and he did not come back. But next year, when we began the Odyssey, he wrote to the Greek professor and wished us luck. Dr. Lees read me a part of the letter, and, as he said, it would have melted a stony heart—which his was not. But there was nothing to be done about it. Many a boy had to drop out like that one, and some of those who got through did it at a sacrifice of health and died in the beginnings of success.

When education was as hard to get as that it took on the glamour of all unattainable things. Boys and girls thought about it and dreamed about it, believed that if they could only have it it would satisfy the very hunger of youth. I think that thirst for knowledge must have been partly a homesickness for older things and deeper associations, natural to warm-blooded young people who grow up in a new community, where the fields are naked and the houses small and crowded, and the struggle for existence is very hard. The bleakness all about them made them eager for the beauty of the human story. In those days the country boys wanted to read the Aeneid and the Odyssey; they had no desire to do shop work or to study stock-farming all day. They hadn't left the home pig-pen to go to the college pig-pen, but to find something as different as possible—if it were only, like Professor Williston, to discover a three-eyed reptile of the carboniferous age. Some of them wanted to be scholars, and they were willing to pay everything that youth can give.

Now, of course, everything is much easier for the Western boy who wants an education. Out in the sand-hill country, in the Colorado mining camps, up in the remote Wyoming timber districts, there are boys who are making a hard struggle to go to college. But the struggle is nowhere so hard as it used to be. As the chorus sings in the "Messiah," the crooked ways have been made straight and the rough places plain.

The country schoolhouses on the prairies are now comfortable, modern buildings; they are kept well painted, and have yards and playgrounds. In every country town the best building is the high school. The new ones are built round a court to get plenty of light, and they have as many fire-escapes as a New York tenement. From these schools the wonderful system of State universities has developed. Some day a very interesting book will be written about our State universities. They grow in influence and power every year, and each has developed a very marked character of its own. The Universities of Nebraska and Kansas, both standing in the midst of rich farming country, have more and more specialized in agriculture and in the sciences which touch it. They have done a great deal to enrich the farming and stock industries of the two States. The University of Wisconsin, situated in the beautiful lake and forest country, has become famous for its study of social problems. The University of Colorado is newer than these others, but it lies in the midst of great natural beauties, at the mouth of Boulder Canyon, and must look forward to a remarkable future. The University of Wyoming is newer still. It is at Laramie, in the sage-brush plains, with a fine spur of mountains behind it. Four or five years ago, when Walter Damrosch made a tour to the coast with the New York Symphony Orchestra, the students engaged the orchestra to come to Laramie and give a performance, and requested the conductor to put upon his programme Dvoräk's symphony, "From the New World," as "the class had been studying it"!

All these State universities are growing and changing as life changes and thought changes; nothing is fixed, and all their traditions are yet to be made. What they are to be depends on the young men and women who study in them and who teach in them.

I wonder whether they are still turning out such brilliant young men as they turned out when they were struggling and poor; and whether the country boy longs for an education now, as he did when it was hard to get? In this present time, which Bishop Beecher once called "the era of extravagance which came in with the automobile," does that fine seriousness still persist in youth whose paths are made easy? But it was not so much seriousness; it was a kind of fire, a really burning ambition and devotion which enabled the young scholars of thirty years ago to do for their State and community the work of several generations in one short lifetime.