From Cather Studies Volume 7

A Portrait of an Artist as a Cultural Icon

Edward Steichen, Vanity Fair, and Willa Cather

The twentieth-century phenomenon of the icon celebrity has a fundamental relationship to the photographic image. The invention of the camera led to the increasing presence of the visual image in American culture. As Catharine R. Stimpson contends in her foreword to Brenda Silver's Virginia Woolf: Icon, the twentieth-century icon "is unthinkable without the presence of the camera." Photography, she explains, "accelerates and reaffirms the process of iconization and celebrity making" through modern modes of mass production (xii). Consider the images of Albert Einstein sitting at his desk with his tousled white hair, Marilyn Monroe standing above the subway grate, or Madonna in her cone-shaped bustier. These images have become infamous portraits, functioning as visual shorthand for each personality in particular and the cultural era each represents in general.

While we recognize the powerful role the iconic figure plays within our culture to create powerful signifiers of ideas, attitudes, historical frameworks, and personal identities, how does one go about becoming an icon? In the case of Willa Cather, her image is documented through her legacy of photographic portraits and her selection of artists Leon Bakst and Nikolai Fechin to paint her portraits. In each of these cases, Cather collaborated with other artists to shape her public image. In the case of the Bakst portrait, she wrote in a letter that after the disappointing result of the portrait, she had resolved to work with other artists only if she could have complete control over the final result. The fireplace, she explained, was the place for images that did not please her (Cather to Duncan M. Vinsonhaler, 13 January 1924). Cather's frank talk about her public image allows us insights into how she managed her career in the increasingly celebrity-driven literary marketplace. Even in the face of her disappointment with Bakst's portrait, Cather followed her own advice and became more careful in her management of her public image. Like other celebrity actors, sports figures, and artists, Cather acknowledged the degree to which celebrity had become a series of collaborations with other artists and celebrity-driven mechanisms. She collaborated throughout her career in a variety of ways, most centrally by working closely with the publicity department at her publishing houses (Houghton and then Knopf), sending out photographs for magazine and newspaper profiles, and joining forces with key image makers within her contemporary celebrity culture. In this essay I place Cather within the context of one such collaboration with top celebrity photographer Edward Steichen, arguing that his 1927 Vanity Fair portrait of Cather was a key moment in defining Cather's iconic status within American culture. Embedded in this argument is the notion that Cather's literary celebrity was established within a larger cultural machine that had, in many ways, already begun to mechanize the creation of celebrities—or at least exploited celebrity through new, sophisticated marketing strategies. Although Cather did much to obfuscate her relationship to that celebrity machinery through her persona, which seemed antagonistic to modernization, my study reveals her shrewd ability to fit that persona into her contemporary celebrity culture. To follow the lines of this argument, I will take a historical approach to link the development of celebrity culture within the technological development of modern image making. In so doing I hope to place Cather's image in context to reveal the importance of Steichen's image and the specific ways in which photographic images of celebrities were created to "speak" in specific ways to viewers. I then turn to a discussion of the celebrity-driven magazine Vanity Fair and the role Steichen had in turning the magazine into a celebrity-making tool through his iconic images of famous writers, actors, and sports figures. Finally, my analysis concludes with a discussion of Cather's public persona, her western image, and the relationships among her clothing, sexuality, and identity as a western writer.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE INVENTION OF MODERN CELEBRITY

Willa Cather came of age in the formative period of modern American celebrity culture. Cultural historian Neil Harris calls the period between 1885 and 1910 the "iconographical revolution," a time when photographs became deeply entrenched in American print, advertising, business, and personal life (199). As Guy Reynolds has noted, "Technologies were changing what 'writing' and being 'a writer' might mean . . . photography and recording equipment would mean that writers would now be more than their words, would have an image and a spoken voice" (4). The introduction of Kodak's box camera, for example, brought picture taking and the consumption of image to a new, personal level. With a simple and effective design, Kodak advertised its new camera to the masses: "Anybody can use the Kodak. Press the button—we do the rest" (Collins 56). Further, the increasing refinement of halftone printing processes beginning in the 1880s meant that magazines and newspapers could cheaply mass-produce photographic-quality images. During her editorial years at McClure's, Cather would have had control in positioning photographs and other images with text—a value she understood well because the magazine touted its visual appeal. When ghost-writing S. S. McClure's autobiography, she included his reflection that "[t]he development of photo-engraving made such a publication [as McClure's] more than possible" (Autobiography 207). Magazine historian David Reed notes from his study of McClure's that photographs played a "prominent role" in the development of the magazine's visual look, since nearly half of the illustrations were in photographic form (49).

Among many early pioneers of American photography, Matthew Brady brought the budding field into the realm of public spectacle. Brady's high-profile celebrity portrait studio capitalized on the public's curiosity about photography by exploiting its even greater curiosity about, as Brady termed them, "illustrious figures." Brady photographed such prominent men and women as Abraham Lincoln, General Robert E. Lee, Jenny Lind, Thomas Cole, Clara Barton, Jefferson Davis, Walt Whitman, and P. T. Barnum ("Matthew Brady's Portraits"). The public flocked to Brady's galleries, paying admission to gaze at images of public figures whose appearances were, aside from engraved portraits in books and newspapers, wholly unknown to them unless they had been lucky enough to see them in person on the street or stage. Brady's celebrity pictures had a larger cultural effect than merely enabling him to profit from the public's desire to see famous faces. Leo Braudy, in his extensive study of fame, suggests that Brady's portraits brought about a shift in the "emotional intimacy" between public figures and their audiences; that is, Brady's photographs were suggestive of the underlying humanity of his subjects.

The larger entertainment world quickly took advantage of the promise Brady demonstrated in capturing the public's curiosity of public figures. Specifically, photography played a key role in propelling actors and actresses into new, unprecedented states of fame. When Jenny Lind, a relatively unknown singer in the United States, toured American cities under the management of P. T. Barnum beginning in 1851, she had her photograph taken in virtually every city she visited and quickly became one of the best-known personalities in the country (Taft 81). Photography allowed for the relatively inexpensive dissemination of actors' and actresses' images through cartes de visite (small picture calling cards) as well as regular picture postcards. By manipulating this new medium, Sarah Bernhardt, one of Cather's favorite stars, significantly changed how the public interacted with famous theatrical actors. Bernhardt, according to Heather McPherson, was part of a "new paradigm of the modern mass-media star" who used photography to "simulate and recreate the visual and emotional dynamics of her performance"; and as a "genius" of publicity, she made sure that newspapers in Europe, England, and the United States carried full-page picture stories related to her every role (78).

During the time of this graphic revolution, Cather was a university student in Lincoln working on her degree and supplementing her income by reviewing touring theatrical productions. In these reviews, Cather distinguished herself by noting the developing role of the star in relation to art; that is, while the stage magazines of the age were full of publicity and gossip, Cather was most interested in those actresses to whom "truth is necessary and all important" (World and Parish 209). Cather lauds actress Mary Anderson in one review, for example, when she turns her back on "fame and flattery," the "most intoxicating of all successes" (World and Parish 202). Cather's reviews during these years demonstrate a sustained interest in the negotiation between the public stage and the private life of the artist. They also show a young woman fascinated by the ways in which celebrity figures threw themselves into the spotlight. In another review, Cather notes her disapproval of "methods of advertising" such as recommending "complexion soap" or having an "agent distribute [an actress's] pictures and press notices" (World and Parish 213). While Cather shows an early preference for those actresses who shy away from self-advertising, she nevertheless paid attention to these facets of her culture.

As American photographers, illustrious figures, and actresses were shaping new cultural modes of celebrity, so too were writers placing themselves within celebrity culture. No figure in American literature represents this shift from the older, genteel model of the writer and the new, image-driven construction of the American author better than Walt Whitman. In the early 1850s, as he made his transition from journalism to the literary world, Whitman brought with him his previous experience in newspapers and printing, in which he would have seen firsthand the "vastly" expanding role of advertising in American culture (Newbury 160). One of the most effective ways Whitman chose to disseminate his public self was by publishing illustrations of himself in his books. Since, as Whitman states in his preface to the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass, "the great poet is the equable man," the visual illustration of himself as "one of the roughs" (50) simultaneously served to illustrate his aesthetic principles and increase his public recognition. So the image of Whitman with an open collar, posing casually with his hand on his hip, was, according to Ed Folsom, "in sharp contrast to the expected iconography of poets' portraits, portraits that conventionally emphasized formality and the face instead of this rough informality, where we see arms, legs, and body" (140). Folsom further notes that Whitman's use of his image in Leaves of Grass had a "highly influential" effect on "the way most American poets portrayed themselves on their book jackets and frontispieces" (135). Kenneth Price recognizes that Whitman "set a new precedent for how a literary project could be advanced through photography, demonstrating photography's power to contribute to celebrity status" (39). The crucial aspect Whitman brought to modern understandings of celebrity authorship is the visual connection between the construction of his appearance and the construction of his poetic project. Text and image work recursively to construct the author's persona, and the public dissemination of the writer's image also guides the public's expectation of that literary project—it necessarily commits the writer to a particular channel of literary output. By incorporating Whitman's poem into the title of her second novel, O Pioneers!, Cather placed her literary project in Whitman's tradition. She further aligned herself, as we will see, through her 1927 Steichen portrait to Whitman's 1855 iconic frontispiece.

GOING PUBLIC

While duties such as buying fiction and poetry, writing the personality-driven Mary Baker G. Eddy series, and managing the magazine's content at McClure's gave Cather the critical experience to manage her own image, when she began her professional writing career she had to build a persona to sell to the public. Her correspondence with her editors at Houghton Mifflin reveals her sensitivity to the crucial role of photographs in book publicity. She often complained that her photographs were not sent out to newspapers and magazines to be published with reviews (Cather to Ferris Greenslet, 20 January 1920); she bemoaned the practice of publishing images of authors at all; she explained that seeing the picture of the author of a book she had meant to read made her decide otherwise, for she found the woman ugly (Cather to Van Tuyll, 24 May [1915]). Some in the public might hold the same prejudice against her, Cather wrote, but authors were different from performers, and while it was important for actresses and singers to be beautiful, authors could not (and should not, judging by the looks of most authors) depend on looks to sell their books (Cather to Van Tuyll, 24 May [1915]). The distinctions Cather made here between publicity and book design were ones she implemented: her picture never appeared on her dust jackets or frontispieces. However, she did approve photographs for use in those materials less connected to her actual work, such as sales booklets, posters, and other promotional materials.

Along with her correspondence, Cather's writing during the mid-1910s documents her concerns over issues of publicity in an image-driven market. In her 1916 short story "The Diamond Mine," written between the publication of The Song of the Lark and My Ántonia, Cather tells the story of a diva deeply concerned with her image. Cather opens her story with the diva, Cressida Garnet, surrounded by "young men with cameras." She stands "good-naturedly posing for them" because "she was too much an American not to believe in publicity." We further are told that she believed "All advertising was good. If it was good for breakfast foods, it was good for a prima donna,—especially for a prima donna who would never be any younger and who had just announced her intention of marrying a fourth time" (67). Cather's larger-than-life representation of her heroine in this story highlights her awareness of the ways in which artists were increasingly flattened into pure product—art and advertising threatened to become one and the same.

The pressure for artists like Cather and her fictional character Cressida Garnet to become public personalities was fueled, in part, by the emergence of the motion picture industry. The "movie star" became a new phenomenon that tied magazines, Hollywood, and advertising together, giving rise to a public personality much different from that of the nineteenth century; that is, these stars could generate significant public interest and fascination not so much by what they did but by the sheer fact of who they were (Susman 223). Richard Schickel argues that the movie celebrity forever altered the expectations the public had toward all public persons: politicians, writers, artists, intellectuals, and even scientists became "performers so that they may become celebrities so that in turn they may exert genuine influence on the general public" (9). This transformation of the public figure into celebrity figure resulted in two competing realities: on the one hand, there was the individual's everyday common life; on the other, there was the life one lived through newspapers and magazines, by which celebrities could be "as familiar to us, in some ways, as our friends and neighbors." The celebrity-as-familiar dominated "enormous amounts" of the public's "psychic energy and attention," even though the closest the average person would ever come to knowing these celebrities was in a halftone photographic image—literally, ink on paper (8).

Celebrity culture formulated itself most powerfully in the pages of popular magazines, and no magazine between the world wars better expressed that celebrity culture than Vanity Fair, a gem in publisher Condé Nast's crown, which included best-selling Vogue and, later, Home and Garden. Vanity Fair was founded in 1914 as a competitor to H. L. Mencken's Smart Set, and Vogue's success allowed Condé Nast to make Vanity Fair a "slick" magazine that incorporated all the costly elements that the financially rocky Smart Set was unable to give its readers: high-quality paper, graphic design, and a plethora of images. Editor Frank Crowninshield had bought Vanity Fair (then a small New York "peekaboo" magazine) in 1913 with a short-lived intention to reincarnate it into a Vogue-like fashion magazine. In 1914, however, he decided that he wanted Vanity Fair to be a magazine "read by people you meet at lunches and dinners" covering "the things people talk about at parties—the arts, sports, theatre, humor, and so forth" (qtd. in Douglas 96). Crowninshield's main strategy for setting the magazine apart from its competitors was to publish stories by European and American avant-garde writers and artists. In particular, Vanity Fair printed some of the first images of Picasso and Matisse, ran poems by Dorothy Parker, and published articles by Robert Benchley. According to magazine historian George Douglas, Vanity Fair "was as appealing to the eye as it was to the tastes of its intended readers . . . it always had substance and it always had guts" (94). With style and substance, Vanity Fair attracted the attention of New York's rich, educated elite, and while it never attained mass-market appeal (circulation hovered below 100,000), the high advertising rates Vanity Fair charged its select advertisers gave Condé Nast a profitable income.

The magazine hit its stride after World War I, when its identity folded perfectly into the mood of the Jazz Age's appetite for style, entertainment, and refinement. Readers of Vanity Fair are said to have conspicuously read the magazine in public and placed copies of the magazine on coffee tables before parties. The magazine's popularity suggests how it so masterfully captured the spirit of the postwar era—witty, playful, experimental, and rich. As John Russell says in his introduction to Vanity Fair: Photographs of an Age, "Vanity Fair was not in the business of aesthetics. It was in the business of getting people talked about" (xvii). Those talked about included the obvious group of Hollywood and Broadway celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson, but also included a surprisingly eclectic group of personalities including scientists, professional tennis players, golfers, boxers, conductors, composers, writers, critics, and even dog breeders. This construction of celebrity within Vanity Fair intermixed full-page portraits of well-known Hollywood and Broadway stars with the less well recognized, putting a glamorous face to writers, intellectuals, and composers while at the same time giving an intellectual flair to the Hollywood celebrity.

Vanity Fair, I suggest, defined celebrity in much more inclusive and even intellectual terms than did other popular magazines of its time. Crowninshield told his readers they were "people of discrimination, clever, and full of a wide and varied culture," and so he assumed that such readers would naturally be interested in the people he and his friends were interested in, from the stage actor to writer to sportswoman (qtd. in Russell xii). One could be a celebrity outside the narrow definition of the "movie star" in the magazine, which invited readers to place themselves imaginatively into celebrity culture through their consumption of the magazine.

THE IMAGE MAKER

A key aspect to the popularity of Vanity Fair stemmed from its use of photography. Crowninshield's belief that fine fashion photography could be elevated to an art form had helped Vogue become one of the most popular fashion magazines of the time, and he had similar revolutionary plans for photography in Vanity Fair. Hiring portrait artists such as Edward Steichen and Man Ray, relative unknowns in the world of high art, Crowninshield gave these photographers "privacy, discretion, unstressed commitment," and paid Steichen (at least) an annual salary of $35,000 (Russell x).

Steichen had been in the art world for more than twenty years by the time he signed onto Vanity Fair. Only six years younger than Cather, by the early 1900s he had become became involved with Alfred Stieglitz's circle as a founding member of "291" and Photo-Secession galleries. During World War I, Steichen helped develop aerial photography, and during this period he also began evaluating his aesthetics. Moving from the early photographic style of soft-focus pictorialism, Steichen's work with aerial photography began to pique his interest in sharp lines and clean detail—the fundamental aesthetic qualities he used to transform portrait photography. By the early 1920s Steichen had attained fame for avant-garde work, yet, according to Joanna Steichen, his "photography brought Steichen more fame than income" (xx). That all changed in 1923 when Steichen accepted his position with Vanity Fair and Vogue. His high Condé Nast salary raised eyebrows among Stieglitz's crowd, who saw Steichen's venture into commercial photography as selling out on their quest to improve the stature of photography in the art world. But according to Joanna Steichen, he believed in "the photograph's potential as a medium for mass communication," viewing his work with magazines as an artistic and aesthetic challenge to raise the everyday, pedestrian magazine photo into an artistic object (xx). No doubt Steichen's knowledge of mass communication directly led to his ability to produce what we now recognize as iconic photographs of his subjects.

A critical aspect of Vanity Fair's attractiveness to both literary and visual artists of the period was its ability to feature new, emerging artists and promote their name recognition within the art world in particular and in highbrow culture in general. This was certainly the case for Cather, who first appeared in a 1922 Vanity Fair article titled "American Novelists Who Have Set Art above Popularity: A Group of Authors Who Have Consistently Stood Out against Philistia." This group included Theodore Dreiser ("among the most extraordinary phenomena of American letters"), James Branch Cabell ("quite unlike anything else in American fiction"), Edith Wharton ("The greatest living American novelist"), Sherwood Anderson ("Foremost among those who are using the novel as a means of criticizing American civilization"), and Cather ("My Ántonia is the best novel ever written by an American woman writer") (Cleveland and Bradlee 58). The magazine's title for this page suggests some critical tensions with its own view of celebrity culture, as it highlights the fact that this group of authors put "Art above Popularity" even though the magazine itself gravitated around celebrity culture. Perhaps the key here is the magazine's reference to the "Philistia," or the lowbrow common reader who did not read Vanity Fair and thereby confirmed the intellectual superiority of those who did. Yet no matter how Vanity Fair positioned these writers to its readers, the fact remains that this first mention in Vanity Fair marked Cather's entrée into the developing celebrity culture of the 1920s. Cather fits into the larger celebrity model Philip Fisher has outlined, in which writers need to place themselves into "a high cultural form of celebrity" while at the same time maintaining "a personal hold on [their] audience" (156). This becomes, then, a balancing act of sorts as authors maintain a dual hold on highbrow and middlebrow audiences.

Although Cather had been a well-known and best-selling writer since her Pulitzer Prize award in 1923, her inclusion into celebrity culture came to fruition in 1927 when her portrait by Steichen was featured in Vanity Fair. A Cather letter reveals that she had dinner plans with Steichen in February 1927, presumably before or just after the sitting (Cather to Mary Virginia Auld, 19 February 1927). Steichen and Cather shared common interests, and his work, which included portraits of Cather's early heroes Eleonora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt, must have fascinated her. There is little documentation detailing Cather's participation in and reaction to the Vanity Fair issue, although what we do have suggests that she was proud of the picture. Blanche Knopf, who worked closely with Cather throughout the 1920s, was so impressed with it she sent a telegram to Cather in Wyoming, writing, "have just seen steichen photograph in vanity fair simply superb don't you think would like to use it too if they permit and you approve with my love" (17 June 1927). Cather replied that by contract the photo belonged to Condé Nast, and so it could not be used for publicity (19 June 1927).

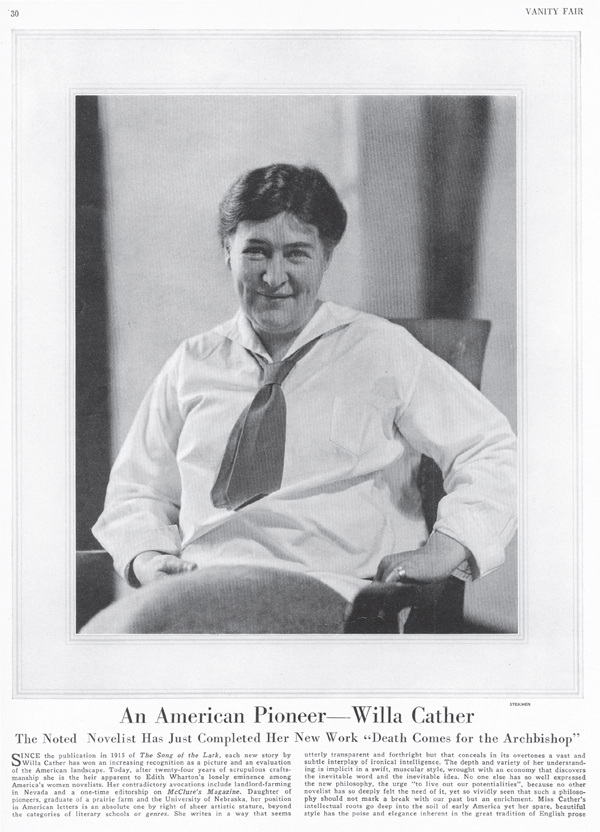

In the Vanity Fair portrait, Cather is featured seated, as Steichen captured most of his writers. She sits as though the viewer is sitting across from her in an intimate discussion, her right hand resting on the armrest of her chair. Cather looks comfortable and self-assured. Titled "An American Pioneer—Willa Cather," the profile employs Cather's most popular and well-known subject matter, the pioneer West. While the title plays up Cather's public persona as a western writer, the subhead explains, "The Noted Novelist Has Just Completed Her New Work 'Death Comes for the Archbishop.'" This profile, then, extended Cather's western image toward her new subject matter, the Southwest.

Fig. 1. Steichen's portrait of Cather as it appeared in Vanity Fair.

Courtesy of Michael Schueth.

Fig. 1. Steichen's portrait of Cather as it appeared in Vanity Fair.

Courtesy of Michael Schueth.

Cather's image in the Steichen photograph corresponds to an image of Cather as a western writer, yet the picture showcases her in other critical ways as well. Her loose-fitting middy blouse and tie together with her gently rolled cuffs suggest an informal moment—as if we have just found the writer in the midst of her work. Like Whitman, whose illustrations and photographs communicated a general attitude that corresponded to his literary work, Cather visually communicates a sense of her "forthright" style. Cather, this photograph suggests, is not regal like Edith Wharton, nor is she so stylish and "fast" as the younger Jazz Age writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald. Through this informal, forthright style, the Cather we see in the pages of Vanity Fair corresponds to the larger literary project she was building. As she laid out her aesthetics in her 1922 essay "The Novel Démeublé": "Whatever is felt upon the page without being specifically named there" informs "the emotional aura of the fact or the thing or the deed that gives high quality to the novel or the drama, as well as to poetry itself" (48-49, 50). Cather believed that art "crowded with physical sensations is no less a catalogue than one crowded with furniture" (50). That there is no visible background or foreground in the picture suggests that Cather's artistic aesthetic informs Steichen's composition. The viewer, then, is given a sense of intimacy with the author because there is nothing intruding between the subject and the viewer. Rather than ridding herself of the pioneer image she had built in advertising and interviews, Cather deepened the iconic resonance of the middy blouse and tie to encompass the entire West. This expansion of place beyond region would not have surprised avid readers of Cather, since the Southwest setting is critical in novels as early as The Song of the Lark (1915) and as recent as The Professor's House (1925).

The text accompanying Cather's photograph adds another level of complexity to the portrait as it positions Cather well at the top of American literature. As "the heir apparent to Edith Wharton's lonely eminence among America's women novelists," Cather, as Vanity Fair saw her, should be regarded as a literary giant, not just as a regionalist. The text ties Cather's aesthetic to the Steichen image: "The depth and variety of her understanding is implicit in a swift, muscular style, wrought with an economy that discovers the inevitable word and the inevitable idea." Yet the magazine writer is also savvy enough to note that Cather's "utterly transparent and forthright" style "conceals in its overtones a vast and subtle interplay of ironical intelligence."

While the photograph generally plays with Cather as western writer, it also resists placing her into categories. Cather's image in this photograph blurs distinctions of feminine/masculine and urban/regional; as the writer of the Vanity Fair article concludes, Cather is "beyond the categories of literary schools or genres." This resistance to classification begs readers to ask, just who is the Willa Cather presented in this photograph? Patricia Johnson counters Joanna Steichen's argument that Steichen captured the "private character in the public faces he photographed" (89-90), arguing that Steichen was a "master of illusion" who "concentrated on the sitter's looks rather than character": "His images of celebrities are chiefly publicity photographs: they extract and polish the public persona much as his advertising photographs create an image for the product. Thus they shaped the sitter's public identity or synthesized an established image. Audiences could feel that by reading a celebrity's image they knew the person beneath the surface" (200-201).

This leads us to ask, how much does the Steichen portrait reflect a deeper sense of the author herself? As the anonymously written text accompanying the portrait notes, while Cather's prose "seems utterly transparent," it also "conceals." Arguably, so too does Steichen's photograph conceal, or perhaps better yet, signify, a host of possible meanings to the viewer. Specifically, I draw on emerging scholarship that places modern women artists in the tradition of the dandy figure. Susan Fillin-Yeh argues that twentieth-century female dandies "took up and deliberately altered that dandy's image inherited from the nineteenth century, refashioning it to their own needs and a new avant-garde art" (130). Fillin-Yeh points to such diverse modernist figures as Georgia O'Keeffe and Coco Chanel as "glimpses of female dandies" we can recognize "through a refocused lens of theory and history," and she suggests that these artists responded to the struggle "to assert individuality with what was still male avant-garde culture" (133). Female dandies of the 1920s challenged the tradition of the male dandy, who was "a creature perfect in externals and careless of anything below the surface, a man dedicated solely to his own perfection through a ritual of taste," who was the "epitome of selfish irresponsibility . . . free from all human commitments that conflict with taste: passions, moralities, ambitions, politics or occupations" (13). But as for the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century male dandy, costume for the early-twentieth-century female dandy was also a source of sexual transgression, especially since male dandyism rejected traditional familial attachments such as marriage and children in favor of showing refinement through the cut of clothing (Moers 18).

Fillin-Yeh points to Greenwich Village as a critical space for early-twentieth-century female dandy figures in the United States. Specifically within the world of Greenwich Village, Cather's home for twenty years, women could seek "distance from bourgeois life and conventional politics" by further distancing themselves from the either/or binaries that had historically limited women's artistic careers (131). By playing with masculinity, women artists simultaneously usurped the guise of traditional male artistic power and exposed that guise as a performance, blurring the line between male and female and ultimately allowing women artists to find power through ambiguity. As with the traditional dandy figure clad in costume, women's take on dandyism continued to operate as a "'social hieroglyphic' that hides, even as it reveals, class and social status and our expectations about them" (2). Fillin-Yeh suggests that such "ambiguities encourage dandies," who are "constantly" and "irrepressibly" drawn to reinvent their appearance (2). Yet the dandy's particular power comes not from clothing alone but moreover from a mysterious sexual je ne sais quoi quality that resides in the figure him or herself. In the case of the female dandy, and unlike the apolitical male dandy, Fillin-Yeh suggests that the performance of masculinity asserts that "the better man is (also) a woman" (14).

The construction of the dandy figure is especially well suited to Cather, because she had long played with the gendered quality of her dress. Going by the ambiguous nickname "Willie," and even less ambiguously signing her name "William Cather, Jr." and "Wm. Cather, M.D.," Cather was, as biographer James Woodress suggests, stymied by her personal ambitions toward a professional career and the cultural limitations of late-nineteenth-century American culture that restricted women's professional opportunities (55-56). Photographs from the late 1880s and early 1890s suggest Cather's playful invention with self-image. Janis P. Stout notes that while photographs of Cather in the early 1890s do evoke a boyish appearance, her clothing nevertheless kept within women's contemporary fashion (Cather 20). The critical point here for this discussion is not whether Cather was cross-dressing but whether from a young age she showed an uncanny ability to experiment with her outward appearance. Even after Cather abandoned her overtly "mannish" style midway through her university years in Lincoln, her softened professional look nevertheless retained hints of the "mannish." Photographs reveal that Cather had a fondness for waist shirts, middy blouses, and a variety of tie styles, including the masculine straight tie. While Cather may have been participating with other female modernists in revising the dandy figure, as with the boyish cross-dressing of her youth, her fashion once again fell in line with contemporary women's fashion. So while the dandified figure Cather represents was subtle, it was, nevertheless, readily available to readers "in the know."

Those "in the know" readers of the Vanity Fair portrait, then, had access to an entirely different reading of this portrait. Perhaps it is this quality of layered meaning that powers the iconic potential of Steichen's Cather portrait. Those who read this photograph within the specific context of the modern dandy figure could read Cather as a specifically urban, New York writer; Cather's middy blouse and tie, which draw attention to aspects of masculine dress, may have offered suggestions about Cather's sexuality. Subtly, this one portrait communicates all of the aspects of Cather's professional and private life that scholars still wrestle with—her play between New York and Nebraska identities, her ambiguity between masculine and feminine, and her aesthetic qualities. The brilliance of the photographic image in this case is that the portrait suggests Cather but does not contain her.

Edward Steichen had the power to build celebrities into iconic figures, and Cather worked to build her post-1927 public image as a reflection of his Vanity Fair portrait. In 1933 and 1940 newspaper features on Cather, for example, she reappears in her middy blouse and tie, affirming the iconic image she created years before. While the Steichen photograph highlights the celebrity culture and image of the 1920s, the outdoorsy, snapshot style of the newspaper photographs presents the same Cather in nature. Regardless of Cather's changes in her subject matter (most notably in Death Comes for the Archbishop and Shadows on the Rock), her public appearance remained the same. The authors of both newspaper features pick up on Cather's well-known image as a writer of the prairie and tie her physical appearance to her literary style. For example, in Dorothy Canfield Fisher's 1933 essay on Cather the subhead reads, "Willa Cather Lived Her Books before She Wrote Them. Her Girlhood Was Spent on the Unfenced Prairie; She Knew the Trials and Triumphs of the Pioneer." In the New York Herald Tribune, Stephen Vincent and Rosemary Benet similarly describe Cather as a real, unaffected person, having "no ivory tower about" her, since "she is too hearty for that." They further describe her appearance as "Of medium height, with clear blue eyes, she gives an impression of great intellectual vitality and serenity combined, calm strength and lively independence" (ix). Cather's photographs along with the writers' descriptions of her in the newspaper profiles strongly suggest the degree to which her "middy blouse image" became iconic to her audience. After twenty-five years of maintaining a particular stylish image, Cather did not allow that image to overtake her writing, but used it to complement her writing.

American icons such as Whitman, Twain, and Chaplin reveal the degree to which dress empowers a particular image of a celebrity to the public, what Sarah Burns calls "key markers of the public self" (223). Although Cather never developed a costume as strict as Twain's post-1906 white suit ensemble, she did develop and maintain a visual look that the public could easily recognize after her break with McClure's. In doing so, Cather built her iconic image in a subtle, but nevertheless effective, visual manner through her white middy blouse with loose-fitting tie. The look, much in the tradition of Whitman, ties Cather to her middle- and working-class readers, since the look was popular, comfortable, and relaxed. Snapshot pictures reveal that this look was an expression of her everyday style.

THE LEGACY OF IMAGES

Cather's public image was further complicated by Cather herself. During 1937 and 1938, Knopf was working with Cather on the Autograph Editions of her collected works. Unlike her other novels, each edition in this collection was personalized with a different Cather portrait in its frontispiece. During this time Cather carefully defined her image through her selection process. Notably, she chose not to use the Steichen photograph in the edition (Stout, Calendar no. 208). Perhaps the reason lies in her growing ambivalence toward celebrity culture at the end of her career. Much like the experience Hemingway would later face, Cather found the price of fame too high to let her work be compromised by Hollywood movies like the disastrous 1934 adaptation of A Lost Lady. Leonard J. Leff argues that Hemingway's participation in his celebrity culture eventually became a "cancer" that "devoured the private person within." The iconic Hemingway could "spark sales and make publisher and author wealthy" simply using his photographs "on reprints, magazine stories, and book club advertisements," but those results came at a high price to the man who wanted to be taken seriously as an artist (198-99). Unfortunately, the literary market that made Cather retreat from public life in the late 1930s was only a sign of growing pressures on writers to serve as larger-than-life personalities first and artists second.

Despite this later ambivalence, Cather was an iconic figure of her culture by the end of the 1930s. Carefully balancing her image with reviews to sell books, maintaining a "style" through her middy blouse and tie that echoed back to Whitman's 1855 portrait, and getting her photograph in Vanity Fair at a critical moment in her career, Cather demonstrated an ability to read her culture's dependency on image to sell books. Beyond her lifetime, images such as Steichen's Vanity Fair portrait have come to stand as powerful evocations of Cather and her West. The University of Nebraska, for example, continues to promote the university and recruit students through photographs taken from Steichen's photo shoot with Cather. In this way, photographs live with us. Celebrity promises a chance for mortal humans to live beyond their years, through cultural memory and history.