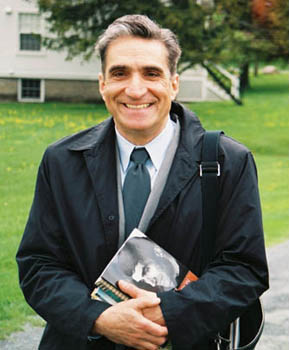

Robert Pinsky Addresses the 2003 International Cather Seminar

Robert Pinsky at Bread

Loaf Robert Pinsky at Bread

Loaf

|

Robert Pinsky was the keynote speaker at the International Cather Seminar 2003 on Thursday, May 29. His theme was the American love of death, derived from his book-length poem An Explanation of America, in which the section "A Love of Death" draws heavily from Willa Cather's My Ántonia. Pinksy drew relationships between My Ántonia, Keats' "Ode to A Nightingale," Homer's The Odyssey, and the creation of identity in the United States. As Americans, he said, "we are still making ourselves up as a people."

Pinsky began his address with John Keats' poem "Ode to a Nightingale," illustrating how, while the narrator anticipates death, he is absorbed into the unconscious mind. Pinsky related Keats' poem to America by stating that generations of people have brought their hungers to America, and that human knowledge is learned, unlike a nightingale. Human knowledge is conscious; a nightingale's knowledge is from instinct, or unconscious.

The power of the unconscious as it relates to death is also evident in many of Cather's stories, especially My Ántonia. Cather's influence on Pinsky became clear as he read from An Explanation of America, beginning with the section "A Love of Death": Imagine a child from Virginia or New Hampshire alone on the prairie eighty years ago . . . Or, imagine the child in a draw that holds a garden Cupped from the limitless motion of the prairie, Head resting against a pumpkin, in evening sun. . . . The ground is warm to the child's cheek, and the wind Is a humming sound in the grass above the draw, Rippling the shadows of the red-green blades. The bubble of the child's heart melts a little, Because the quiet of that air and earth Is like the shadow of a peaceful death— Limitless and potential, a kind of space Where one dissolves to become a part of something Entire . . . whether of sun and air, or goodness And knowledge, it does not matter to the child (21-2).

Pinsky's re-imagining of Jim Burden in the garden scene from My Ántonia, as he explained, highlights the child's hunger for unconscious knowledge, or his desire to become like Keats' nightingale, like the land itself.

The land, as Pinsky observes in "A Love of Death," can be a force of "obliterating strangeness" both to immigrants and to visitors from the city. Near the end of My Ántonia, as Jim Burden returns home after being away for twenty years, the changes in the country distance him from it, and he sees his life as an interminable journey. In this way, Pinsky argues, making a home is perpetual and, like Jim, who hasn't settled anywhere, Americans have not yet accomplished a home-making. Pinsky continues in "A Love of Death": The obliterating strangeness and the spaces Are as hard to imagine as the love of death . . . Which is the love of an entire strangeness, The contagious blankness of a quiet plain. Imagine that a man, who had seen a prairie, Should write a poem about a Dark or Shadow That seemed to be both his, and the prairie's—as if The shadow proved that he was not a man, But something that lived in quiet, like the grass. Imagine that the man who writes that poem, Stunned by the loneliness of that wide pelt, Should prove to himself that he was like a shadow Or like an animal living in the dark. In the dark proof he finds in his poem, the man Might come to think of himself as the very prairie, The sod itself, not lonely, and immune to death. (23)

According to Pinsky, this lack of an established home is the reason why we have created pop culture. He said it is "a brilliant, surrogate, temporary solution." Americans have shifted the focus of their imaginations.

Robert Pinsky signs a book for

Colloquium member Josh Dolezal. Photos, Jim

Rosowski

Robert Pinsky signs a book for

Colloquium member Josh Dolezal. Photos, Jim

Rosowski

Image of Robert Pinsky signs a book for

Colloquium member Andy Jewell. Photos, Jim

Rosowski

Image of Robert Pinsky signs a book for

Colloquium member Andy Jewell. Photos, Jim

Rosowski

By living in pop culture, Americans can focus on external, consciously created life, rather than on finishing their job of creating a stable home.

Pinsky reminded his audience that Jim has spent the last twenty years traveling, gaining knowledge and life experiences much like Odysseus did in Homer's The Odyssey. All of these are behaviors of the conscious mind. Jim has been seeking something. When he returns home, however, he becomes absorbed in the unconscious. Upon his return, he feels restless in the city and heads for the prairie, where he and Ántonia spent time together in their youth. Pinsky asserted athat by containing so many minute details, Jim's description of the prairie makes it so small that it becomes a vastness, like the descriptions in Keats' poem. Pinsky lauded Cather for her courage in addressing the question: how do we make a home in this huge space?

Jim's memories, especially of the Shimeradas, speak to issues of memory and culture in America. These, too, are related to The Odyssey because when Odysseus is on Circe's island, he loses his memory and, according to Pinsky, the single eye of Polyphemus represents lack of culture. A concern of Pinsky's and Cather's is the national loss of memory and culture, which emerges in My Ántonia as a traveling man commits suicide in a threshing machine. When the farm workers remove him from the thresher, they find poetry about his home in the old country in his pocket. The scene reappears in Pinsky's "A Love of Death": Some people are threshing in the terrible heat With horses and machines,cutting bands And shoveling amid the clatter of the threshers, The chaff in prickly clouds and the naked sun Burning as if it could set the chaff on fire. . . . A man, A tramp, comes laboring across the stubble Like a mirage against that blank horizon, Laboring in his torn shoes toward the tall Mirage-like images of the tilted threshers Clattering in the heat. Because the Swedes Or Germans have no beer, or else because They cannot speak his language properly, Or for some reason one cannot imagine, The man climbs up on a thresher and cuts bands A minute or two, then waves to one of the people, A young girl or a child, and jumps head-first Into the sucking mouth of the machine, Where he is wedged and beat and cut to pieces- While the people shout and run in the clouds of chaff, Like lost mirages on the pelt of prairie. (22-3)

Pinsky spoke about how Cather's ferocity, her terror of losing our country, came through in her fiction. He asserted that in the last chapter of My Ántonia American readers reflect upon how Jim Burden is doing, not Ántonia. Americans need to see that Jim has not succeeded. He does not have a home, and when he returns to where he grew up, where his home used to be, he is overwhelmed with a sense of dread at the obliterating strangeness.

Pinsky ended his address with a discussion of the role of memory and poetry in the preservation of culture. He asserted that American art indicates that there is something serious and conflicted about the national identity. He warned, "Ambivalence toward memory is ambivalence toward provincialism," then closed with the message that writers help to fill the gap between memory, culture, and the obliterating strangeness by providing something on a smaller, more human scale. To this end, he closes "A Love of Death" with a passage addressed to his daughter, as the entire narrative of An Explanation of America has been: None of this happens precisely as I try To imagine that it does, in the empty plains, And yet it happens in the imagination Of part of the country: not in any place More than another, on the map, but rather Like a place, where you and I have never been And need to try to imagine—place like a prairie Where immigrants, in the obliterating strangeness, Thirst for the wide contagion of the shadow Of prairie—where you and I, with our other ways, More like the cities or the hills or trees, Less like the clear blank spaces with their potential, Are like strangers in a place we must imagine. (23-4)

An Explanation of America is published by the Princeton University Press, 1979.