Willa Cather North by Northeast

Cather Related Site-Seeing North of New York City and East of Ohio

On the Martyrs' Trail:

Indians and Missionaries in the Champlain and Mohawk Valleys

Part 1: Cather, Missionaries, and History

Tour written by Sherrill Harbison

The Five Colleges, Amherst, Massachusetts

Our Lady of Martyrs, Auriesville Shrine

Our Lady of Martyrs, Auriesville Shrine

In Shadows on the Rock, Cather writes that to twelve year-old Cécile Auclair, the martyrdoms of the early Church "never seemed…half so wonderful or so terrible as the martyrdoms of Father Brébeuf, Father Lalemant, Father Jogues, and their intrepid companions" in New France. What could be worse, she wonders, than "the tortures the Jesuit missionaries endured at the hands of the Iroquois, in those savage, interminable forests?"

To tell the truth, not much. The trials of one of these men, Father Isaac Jogues, were endured in the Champlain and Mohawk Valleys, and they were astonishing by any standard.

St. Isaac Jogues(1607-46)

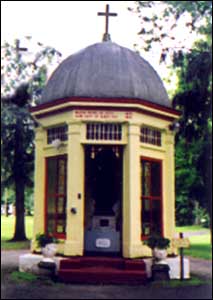

First chapel at Auriesville, erected 1885.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

First chapel at Auriesville, erected 1885.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

In 1642 Father Isaac Jogues was traveling up the St. Lawrence to his mission in Huronia when he was captured near Three Rivers by a band of Mohawks—bitter enemies of the Hurons, and one of the seven Iroquois nations then allied with the English and Dutch against the French and Algonquians. The Jesuits (Jogues and two companions, René Goupil and Guillaume Couture) were first stripped naked and beaten to unconsciousness with clubs, their fingernails torn out and fingers gnawed until the bones were in splinters, before being taken on the long journey south to Mohawk country. The route took them up the Richelieu River and the 103-mile length of Lake Champlain. On Isle La Motte (near the entrance to the lake) and further south on Jogues Island (near the town of Westport N.Y.) they were tortured again—more beatings, hair and beards torn out, and forced to run the gauntlet (called by Jogues "the narrow road to paradise"). After ten days they reached the foot of Lake George, from where they took an overland trail to the Hudson and then to the Mohawk River near the present location of Amsterdam, N.Y. Burdened with heavy packs and weakened by suffering and starvation, they arrived at the Indian "Castle" at Ossernenon (Auriesville, N.Y.), only to face weeks of more ceremonial torture. Children threw live coals on their flesh for sport; Jogues was pinioned to the ground in pouring rain for three days with his oozing wounds, had his thumb cut off with a scallop shell, and was hung for several days by the wrists. René Goupil became the first Catholic martyr of the Mohawk Valley when he was cut down for making the sign of the cross over an Indian child.

Father Jogues remained in captivity at Ossernenon as a slave for fourteen months, suffering abuse apparently beyond natural endurance. His missionary zeal was so great that he ignored possibilities of escape, and was eventually given freedom to travel between towns unguarded. But not indefinitely. On a fishing trip near Fort Orange (Albany), he learned he was to be killed on return to Ossernenon, and with the aid of the Dutch, he escaped first to Manhattan and then back to France in 1643. He was received as a hero by both the king and the pope, who gave him special dispensation to say mass with his mutilated hands. (Was Jogues one inspiration for the mutilated hands in Cather's last, unfinished novel about torture, Hard Punishments?) Despite all this, the following spring (1644), Jogues would return to Canada.

View of the Mohawk Valley from Auriesville Shrine.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

View of the Mohawk Valley from Auriesville Shrine.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

Because of his experience with the Mohawks, Father Jogues was enlisted in 1645 to mediate among the Mohawks, French and Algonquians for a new peace treaty. This time, having been warned that his religion would put him in danger, he wore civilian clothes on the route along the waterways he had first traveled in captivity. As an ambassador from a nation the Mohawks now wished to accommodate, he was well received at Ossernenon, and his peace mission succeeded.

But the story was not yet finished. As long as the Mohawks' souls remained unsaved, Jogues could not rest. Despite warnings, he set out to Ossernenon via Lake Champlain a third time in 1646. Without realizing it, however, he had already made a fatal mistake. After his last ambassadorial visit, sickness had broken out in the tribe and a blight had fallen on the crops. A box of religious articles Jogues had left behind was assumed to contain the evil spirits responsible for the calamities. Thus, shortly after his last arrival at Ossernenon on October 18, 1646, a tomahawk was buried in Jogues' brain. As a warning to future French missionaries, his head was impaled on a palisade picket facing north.

Cécile Auclair was certainly correct to recognize that many of the early Christian martyrs suffered more quickly and finally than these early Jesuit missionaries. But what was worse, to all appearances the Jesuits' work seemed absolutely without profit. Apart from some infant baptisms, they accomplished nothing—not one adult Mohawk was converted. Little wonder that Euclide Auclair, rational scientist that he is, wonders "whether there had not been a good deal of misplaced heroism in the Canadian missions,—a waste of rare qualities which did nobody any good." Auclair consoles himself with the thought that their sacrifice may be like "the box of precious ointment that was acceptable to our Savior," whereas he himself was "like the disciples who thought it might have been used better in another way." The Church eventually confirmed his surmise when Father Isaac Jogues and seven other North American martyrs were canonized in 1930.

Lake Champlain from the Champlain Islands.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

Lake Champlain from the Champlain Islands.

Photo by Sherrill Harbison.

Tracing the Route: Lake Champlain

Intensified Iroquois raids into Quebec and the failure of the missionaries to secure peace prompted the French to build several garrisoned forts in the Richelieu and Champlain Valleys. The southernmost of these, the double-log palisaded Fort St. Anne, completed in 1666, was situated at the presumed torture-site of Father Jogues on Isle La Motte in northern Lake Champlain, the first European settlement in what would later become Vermont. Interestingly enough, there is an indirect Cather connection to this site as well. We have information about the first brutal winter French soldiers spent at Fort St. Anne thanks to the record of the Sulpician monk François Dollier de Casson, a military chaplain of unusual strength, intelligence, and personality on whom Cather partly modeled Father Hector St. Cyr. (See John Murphy's Quebec and Montreal tour.)

Dollier de Casson arrived in Canada from France in 1666, and journeyed to Fort St. Anne on snowshoes not long afterward, escorted by four others including the Montreal merchant Jacques Le Ber, father of the recluse Jeanne Le Ber. At the fort they found forty of the sixty soldiers desperately sick with scurvy, living only on bacon and spoiled flour. On Le Ber's return to Montreal he arranged for a sledge full of food to be sent to the sick men.

Dollier de Casson stayed at Fort St. Anne all winter. When not preparing men for death and helping in the infirmary, he wrote, "I went to the place between the bastions of the fort where the snow was trampled down, to take the air and run back and forth… Anyone who saw me would have thought me crazy, had he not known how essential such violent exercise was to keep off the illness. It was certainly funny to watch me say the breviary on the run, but I had no other time, and believed I should use it in saying my office…" (Hill 32).

Two years later, in the spring of 1668, Bishop Laval visited Fort St. Anne, arriving in a bark canoe with only a wooden cross and simple mitre. (As Cather wrote in Shadows on the Rock, "the old bishop had to make long journeys in canoes and sledges, very fatiguing at his age, [but] he undertook them without a murmur.") By that time an interval of better relations with the Iroquois had begun, and Laval may have been able to baptize some converts.

St. Anne's Shrine, Isle La Motte

St. Anne's Shrine, Isle La Motte

With the valley temporarily at peace, Fort St. Anne was abandoned in 1671. Today no trace of it remains, but in its place on the still-French-flavored Isle La Motte is the charmingly rustic St. Anne's Shrine, commemorating the fort as the first Catholic outpost in Vermont. Edmundite Brothers occupy the small residence and conduct services in the outdoor chapel. A statue of the lake's namesake, the French explorer and cartographer Samuel de Champlain, stands near the beach where he, too, had first landed.

The second torture site of Jogues' Mohawk captivity journey was the tiny, wooded, and otherwise unremarkable Jogues Island, which can be seen from the lakeshore just south of Westport, N.Y. (also called Cole Island).

Lake George, New York

A memorial statue to Father Jogues stands in Battlefield Park in Lake George N.Y., commemorating the martyr's journeys on this lake. Jogues was the first Frenchman to see Lake George, which he named Lac du St-Sacrament. (Lake George web site)

Albany, The New York State Museum

The Mohawk Iroquois Village exhibit at this museum is highly recommended if you are interested in pre-contact Iroquois life as it would have existed at Ossernenon. The exhibit includes three dioramas depicting life in a Mohawk Iroquois village about 1600, before European influence greatly changed the culture. Included is a scale model of an Iroquois village, part of a full sized longhouse with furnishings, and an agricultural field. There are also artifacts and eyewitness accounts, including Brébeuf's from the Jesuit Relations. (Museum website)

Ossernenon Mohawk Castle The National Shrine of North American Martyrs, Auriesville, New York

Probably the most elaborate Catholic shrine in America is located at the site of the Ossernenon Mohawk village at Auriesville, N.Y., above the Mohawk River, dedicated to the eight North American martyrs—not only the missionaries Jogues, Goupil, and Lalande, who lost their lives here at Ossernenon, but to the five who died at the Huron missions in Ontario—Jean de Brébeuf, Noel Chabanel, Charles Garnier, Gabriel Lalemant, and Antoine Daniel. The fates of three of these men are discussed in Cather's novel. Cécile Auclair is astonished that bones from Brébeuf's skull, mixed with gruel, could convert an English sailor; Chabanel's particular unsuitability to missionary life was an inspiration to Father Hector St. Cyr; and Father Hector himself attested that Garnier "had learned the Huron language so thoroughly that the Indians said there was nothing more to teach him."

Ossernenon was abandoned by the Mohawks in 1660. Between 1763-1832 the Jesuits were expelled from North America, and not until their return in the nineteenth century, bringing with them an intense interest in their predecessors, were the records of the earlier missionaries sought out and published as the Jesuit Relations. The site of the village at Ossernenon was identified by archeologists in 1884, and the following year it was purchased by the Church as a holy site. Pilgrimages began there in 1886; two years later, 1200 communions were taken at its open-air chapel on a single day. Plans for a building to accommodate such numbers were delayed until after the Great War; the huge church called the Coliseum—with seats for 6500 and standing room for 3500 more—was dedicated in 1931.

There are many attractive and evocative small buildings, shrines, and views at this large and handsomely situated site, including its earliest chapel erected in 1885 (see photo above). The shrine also pays homage to the Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (1656-80), a Christian Mohawk born here ten years after Jogues' death.

The Auriesville Shrine/Ossernenon Mohawk Castle is a short distance from Cherry Valley, where Cather stayed with Isabelle McClung in 1911. (See Sherrill Harbison's Cherry Valley tour.) There is no record of Cather having visited the shrine, but since it was already a major attraction in the area, she could not have helped being aware of it—a full twenty years before taking up the missionaries' stories for Shadows on the Rock.

Sources

Russell P. Bellico, Chronicles of Lake Champlain: Journeys in War and Peace. (Fleischmanns, N.Y., 1999)

Pierre Biron, Recherche sur les noms de lieu. Petite histoire du lac Champlain http://www.voileevasion.qc.ca/lac_champlain_toponymie.htm (2002)

T. Wood Clarke, The Bloody Mohawk (New York, 1940)

Guy Omeron Coolidge, The French Occupation of the Champlain Valley from 1609 to 1759 (Marmaroneck, N.Y. 1989)

Francis X. Curran, Ossernenon Mohawk Castle 1642-1660, Martyrs Shrine 1885-1985 (Auriesville, N.Y., 1985)

Ralph Nading Hill, Lake Champlain, Key to Liberty (Montpelier, VT, 1978)

John Howland, Jr., ed., Exploring Lake Champlain and its Highlands (Burlington, VT, 1981)

James P. Millard, America's Historic Lakes: Lake Champlain and Lake George Historical Site. www.historiclakes.org (2002)

Go to Part 2, How to see the Champlain and Mohawk Valleys, with Dining and Accommodations

Tour written by Sherrill Harbison, The Five Colleges, Amherst, Massachusetts - 2003

Sponsored by the Cather Project, 2003