From Cather Studies Volume 6

The Not-So-Great War

Cather Family Letters and the Spanish-American War

"The splendid little war" is the phrase Secretary of State John Hay used to refer to the altercation with Spain occurring during his term of office. Since then the name and the war have both undergone reappraisal. In 1996 historian Thomas G. Paterson writes of "the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War" and another more recent revisionist historian, Louis A. Perez Jr., prefers to discuss the just as inclusive but less cumbersome appellation of "War of 1898." For U.S. combatants and the nation that sent them, this conflict was known simply—and perhaps imperialistically— as the Spanish-American War. From a perspective of a century later, the war appears to be a brief rehearsal for conflicts to come. In the Spanish-American War, four thousand U.S. military personnel lost their lives: four hundred in combat and thirty-six hundred to infections, disease, food contamination, and unsafe, unsanitary health conditions. Another four thousand American troops died during the Philippine insurrection that began as a direct result of the official Treaty of Paris signed December 10, 1898. In the Philippines Americans really fought two separate wars. After the treaty in which Spain ceded the Philippine Islands to the United States, U.S. forces found themselves fighting the Filipino forces of their previous ally—rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo—who had been so instrumental in defeating Spain only months earlier.

The Spanish-American War was in many ways a modern war, with several innovations that changed the battlefield forever. A hot air balloon was used for reconnaissance before the battles of San Juan Heights and San Juan Hill; for the first time film footage recorded action on ships and in land battles; Gatling guns peppered approaching forces. Yet it was also the last of the old battle styles as well. Cavalry was central to combat, but horses were more decorative than strategic in the great wars to come in the twentieth century (Lynch interview).

War came to Webster County, Nebraska, in the spring of 1898, and young men left farms to scatter as far away as Cuba and the Philippines in answer to the call for volunteers. Grosvenor (G. P.) Cather was a fifteen-year-old farm boy when the Spanish-American War broke out. He and his twelve-year-old twin brothers, Frank and Oscar, kept up a correspondence with three young men from their community who joined the Nebraska Volunteer Infantry. Two of the men were sent to Florida and Cuba and one to the Philippines; the letters they wrote back home to the teenaged sons of George P. Cather helped shape the boys' expectations of battle scenes on land and sea.[1]

In terms of military history, the small cache of letters is unremarkable. The three men writing are enlisted men, not the decision makers that military historians traditionally chronicle. The men rarely hold a vantage point on the battlefield; instead they write of everyday life at stateside camps, on troopships, or in foreign camps. As for news of the war, they rarely have more than rumors to pass on. The anonymity of the source of news about the war efforts, however, brings home universal complaints of any enlisted man in any war. He is a player on a game board—at best moved by some shrewd officers into strategic locations and put into a position of affecting the outcome of the wargame, at worst a forgotten game piece stacked beside the board, to be held in abeyance until some turn of events forces his participation. Perhaps he will not have a significant part to play at all, he fears.

Willa Cather was only twenty-five and writing with the Pittsburgh Leader for the few months of the war in 1898. Among her other responsibilities, she handled war dispatches from Cuba (Stout 53). Her job kept war news before her, and she was probably speaking from personal experience when she wrote her friend Frances Gere that newspapers were puffing up the war news to create reader interest (qtd. in Woodress 94). As was her cousins' in Nebraska, Cather's role was vicarious, but it offered her—and them—"war experience" before the Lost Generation writers of the next war sailed for their European conflict. Twenty years later Cather's oldest cousin, G. P., would be Webster County's first casualty in the Great War. As reported in the Blue Hill (NE) Leader and reprinted in the Red Cloud (NE) Argus, "Lieutenant Cather was the first Webster County man to enter overseas service, the first one from the county to give up his life in the war against Prussianism and the first officer from Nebraska to fall on the western front in France" (Ray Collection, June 20, 1918). Cather's 1922 novel One of Ours would be a tribute to him and to all those who lost their lives. In a real sense, it would be a tribute to all who fought in the war and all who fought for what her hero fought for—personal freedom. Claude Wheeler has some of Cather's own longings in his persona—great hopes for the future, a desire to escape reminiscent of the Revolt from the Village school of the era, a love of France, and a sense of the stifling effects of family and home country on personal dreams.

Janis P. Stout discusses the parallels between Claude and Willa Cather in her biography of Cather (169-71). Even in the choice of a name for her protagonist, Cather aligns herself with Claude Wheeler by reversing her own initials. Claude is a self-conscious young man on the threshold of adulthood. He tries hard to be a face in the crowd, to be the son his parents want him to be, to marry the girl from a neighboring farm, and to live a life similar to those of family and friends around him. His hopes for such a world fall apart before the coming of World War I offers him a way out. Like a deus ex machina, war in Europe lifts him from the Nebraska plains, leaving home problems unresolved.

The prototype for Claude Wheeler, Cather's cousin G. P., greeted departure for the war with the same sense of release as did Claude. Fifteen years older than his fictional counterpart, however, G.P. knew more about war and the military. Meant to typify the thousands of young soldiers innocently leaving the farms for the excitement of military adventure, Claude is more like the youthful G.P. who received letters from soldiers in 1898 than he is to the thirty-five-year-old man who went off to war in 1917.

None of the letters written to the three soldiers by G.P. or his brothers survives; only the responses to questions asked or to information provided and advice offered in the soldiers' letters give us the images of three young men at home learning about the war and the manly activity of war. The three soldiers were all from Bladen, Nebraska, and the surrounding farmlands. Though they knew one another, the three were not close friends and kept track of one another in their travels more through information in letters from home than from crossing paths with one another.

Two of the three young men writing to the Cathers were farmhands who regularly worked for the boys' father. Unused to the niceties of letterwriting, their concerns are elemental: food, health, weather, news from home and about each other. Oley Iverson first writes from Camp Omaha, only a few hours by buggy from the farm where he grew up. Iverson's experiences in camp altered his views. For one, he had assumed that the big and brawny recruits are the most likely to pass the physical examinations for entrance into the regiment; instead, he writes, "It seems as if the largest and the stoutest men have more trouble passing than the little fellers have. There's lots of big stout looking [men] . . . rejected everyday. All the men that we thought was sure to pass in our company was rejected" (Ray Collection, July 11, 1898).

There was no rationing at stateside camps, according to Iverson's catalog: "Each man is allowed one pound of beef a day and bread, beans, potatoes, coffee and sugar and sometime we get tomatoes" (Ray Collection, July 18, 1898). After moving on to Jacksonville, Florida, he writes, "We have dried fruit three times a day—fresh meat once, plenty of potatoes, tomatoes, onions, rice and lots of good bread. It is true that it is not cooked as good as it might be, but we have no fancy cook stoves to cook on or it would be better. But when everything has to be cooked outdoor, it makes lots of difference" (Ray Collection, October 14, 1898).

The next exotic clime on Iverson's tour of duty is Savannah, Georgia. Writing October 29, 1898, he says Company I, Third Regiment of the Nebraska Volunteer Infantry are bivouacked "two miles southeast of town. The streetcars run out to the camp so it makes it quite handy when we want to go to town. I was down one day this week and took in the city. It's a nice place. It beats Grand Island [Nebraska] all to pieces. We are camped where the rebels were camped at the time when Sherman captured the city. There is still a lot of old breastwork left to mark the place. I like Georgia ever so much better than I did Florida" (Ray Collection).

A staunch Republican, as were the Cathers, Iverson mentions the most illustrious member of the regiment, Nebraska's favorite son, Col. William Jennings Bryan, who was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate against William McKinley for president in 1896. "I must tell you that I like Col. Bryan very much," he writes. "I think he is a mighty fine fellow. He is just as common as any of the boys" (Ray Collection, July 11, 1898). A week later he suggests facetiously that even Bryan might be changed by his war experiences: "Bryan is all right but his politics need fixing and we will have that fixed when we get back from war. I think he will be a Republican then" (Ray Collection, July 18, 1898).

H. C. Gress sticks with the unvarnished truth as he sees it in his first letter after arriving at Camp Cuba Libra, near Panama Park, Florida: "We left Omaha last Monday a week ago for Jacksonville, Florida, which we reached Friday morning at 8:00 o'clock. We had a long ride and a good time. We all like it pretty well here now, but we didn't like it at first. I like it fine. The Army is all right. I have good health. I feel better than I have felt in the last two years. It is awful hot down here though" (Ray Collection, July 27, 1898).

Gress spent the rest of his four months of service in Florida. In October he wrote to G.P. that he hadn't written because he was sick: "I am in the hospital now and I have been here two weeks today." No doubt largely because of his unspecified malady, Gress's view of the state of Florida had changed: "I don't like it in Florida very well. I would rather be in old Nebraska where I was raised. The climate agrees with my health better. Florida doesn't agree with my health at all but I guess I will have to stand it till they see fit to send me home. I hope it will be soon for I know if I get back to Nebraska I will be all right. I will get my health again" (Ray Collection, October 2, 1898).

Furloughed and discharged less than a month later, Gress was back in Bladen, Nebraska, in early November and wrote about his return to G. P., who had gone off to a junior college: "Everybody is husking corn and I hafto sit around and watch them. I am not able to work this fall. I don't expect I will be able to work any all fall. I get awful tired of sitting around doing nothing. I only wish I could get out and work." He ends with a sad lament of the world weary soldier: "Oh yes I received a letter from my old chum [Oley]. He said they was getting along fine now they are practicing shooting. I suppose they have a hot time alright—they can have all the fun they want to, but I have had my fun down there—all I care about anyhow" (Ray Collection, November 4, 1898).

The third correspondent, Bruce Payne, was a student from the university in Lincoln and a distant family member. He wrote G. P. from San Francisco telling him of the wonders to be experienced even in the far reaches of the United States: "My tentmates and I were over to the sea chasing waves and picking up shells," wonders indeed to a landlocked Nebraskan (Ray Collection, June 4, 1898). The troop transport crossing from Oakland to San Francisco (the Bay Bridge hadn't been built in 1898) is the Merino, which Payne describes as "the largest transport in the world." A hint of danger haunted the exotic, unfamiliar world, particularly since in a declared war, "the enemy" is identified: "There are many Spanish people living here in Frisco," Payne goes on. "We are careful about eating things that people give us. The people give us oranges, throw them at us, great large ones big as your two fists. They cost only 5 cts a dozen here." Golden Gate Park becomes an exotic wild animal preserve—"lions, buffalo, deer, elk, birds and many beautiful tropical flowers" as well as "a grizzly bear there that weighed over 1000 pounds." Such exotic sights could only make the young man receiving the letters envious. Seasickness, missed promotions, boredom, and waiting come up in subsequent letters, but the bright promise of exotic locales overwhelms such dull and vaguely prosaic topics.

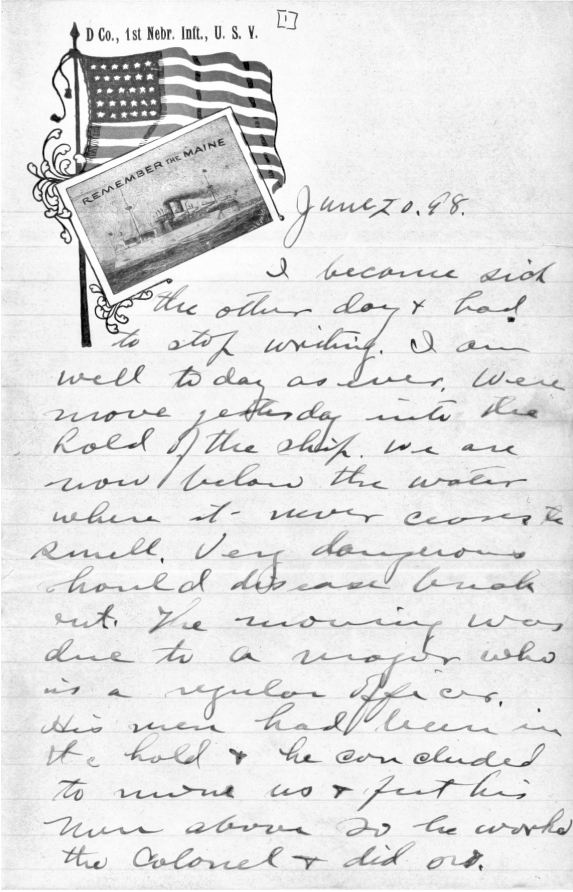

Since he was the most educated of the three correspondents, Payne's letters are the most literate; they connect the exotic world with the known world of G.P. and his brothers: on the voyage to the Philippines, for instance, he saw a whale "as long as your barn is wide." Flying fish have wings that "look just like locust's wings." Miraculously, the Pacific Ocean is rendered in the images familiar to the Nebraska farm boys. In his second letter Payne takes G.P. on a tour of his troop ship, the USS Senator. Again, he emphasizes the gigantic proportions of the ship, with room for one thousand troops. "The bunks in the lower deck are not very pleasant places," he finally admits. "It is a pretty hard place to 'Remember the Maine' as one fellow put it" (June 21, 1898). The ironic reference to the most famous battle cry of the war takes on a double irony in terms of the stationery Payne uses (see fig. 1). The stars and stripes wave in color in the top left corner on both the envelope and page. Superimposed on the flag is the outline of a calling card printed by D Company, First Nebraska Infantry, United States Volunteers. The card reads, "Remember the Maine," a triumph of advertising and jingoism since the sinking of the Maine in Havana Harbor occurred February 15, 1898, less than four months before Payne's first letter.

Responding to questions from G.P. and his brothers, the correspondents describe their rifles: "You wanted to know what size my rifle was," writes Gress. "It is a 45 single shot Springfield. It is just a dandy" (Ray Collection, July 27, 1898). The Springfield was standard issue among state militia and was the oldest and least effective weapon in widespread use (Lynch interview). The young boys clearly want to hear more about guns and rifles, because Gress adds in a later letter: "No, we haven't done any shooting with our guns yet. We don't shoot with them when we drill." Not wanting to disappoint G.P. and his brothers, however, Gress adds all the excitement he can muster as he goes on: "The noncommissioned officers had a sham battle this morning. They had a hot time for a little while. One of our men got one of his teeth knocked out but didn't hurt him[self] very bad" (Ray Collection, August 13, 1898). R. B. Payne seems aware of the advantages and disadvantages of the rifles in use on both sides when he writes magisterially from Camp Dewey "near Manila": "The Spanish have the Mauser rifles. They repeat five times, and [are] not a deadly weapon as they fire small steel bullets. The Krag-Jogensen rifle which the regulars have shoots the same kind of a ball. They say that these balls will wound a man but [are] not likely to kill him, so it will take two men to carry off the wounded man whereas if he had been killed, no one would drop out to care for him. In this lies the advantage of the steel ball" (Ray Collection, August 8, 1898).

Payne does not go so far as to question the firepower of the rifles

he and his fellow Nebraska volunteers have been issued, however:

Fig. 1. Letter from Bruce Payne to G.P. Cather. George Cather Ray Collection,

Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Libraries.

"The Springfield shoots a lead ball which flattens when it strikes

a man and makes a ghastly wound" (Ray Collection, August 8,

1898).

Fig. 1. Letter from Bruce Payne to G.P. Cather. George Cather Ray Collection,

Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Libraries.

"The Springfield shoots a lead ball which flattens when it strikes

a man and makes a ghastly wound" (Ray Collection, August 8,

1898).

In May 1899 in the Philippines—three months after the identity of "the enemy" had changed from the Spanish imperialists to the homegrown Philippine insurgents—Payne writes of an armed encounter with the enemy: "A tree back of our lines had 11 bullet holes in it up as high as a man and in all there were 26 bullet holes in the tree. It seemed a miracle that so few of us were killed. This pencil that I am writing with was taken from one of the dead enemy. I was the first man in the trenches so I got a Mauser there, could have got another but could not carry it. In this fight my best friend in the army was wounded. The colonel was killed" (Ray Collection, May 2, 1899).

Now the possessor of a Mauser, Payne brags: "A friend and I were up to the 1st Brigade firing line. We had some nice shooting there. I proved to him that a Mauser was better than a Krag- Jorgensen" (Ray Collection, May 2, 1898). The Mauser and the pencil are both war trophies.

The few skirmishes with "the enemy," the images of rifle fire, and the tales of battle make exciting reading back home. A closer look reveals the boredom, the loneliness, an awareness of lost opportunities— friends marrying, farms flourishing, holdings growing larger. No doubt the Cather boys were more interested in Philippine battle stories and the antics of the pet monkeys in camp than in R. B. Payne's decision to study Spanish to fill his time or the illnesses that plagued him and the bugs that attacked him in his bed. What would the three Cather boys have gleaned from Oley Iverson's adventure in Havana after the treaty?

On Thursday I and another feller went to Havana and we took a boat and went over to Mossy and Cabanas Castles and went all through them. The soldiers are not allowed to go there on account of the yellow fever. There are guards all around them but we got in anyway. . . . the small pox did not get started in the Third but a good [many] of the boys in the 161st Indiana Regiment have died with it. The Third Nebraska has been healthier since we arrived in Cuba than we were before. We have only lost two men: one of them was the man that I told you of that got drunk and the other one died from vaccination. (Ray Collection, February 28, 1899)

Iverson reports that even Col. Bryan "is sick a good share of the time." Iverson's loyalties to the Republican Party do not prevent him from defending the "Great Commoner" from a question assuming partisanship: "And you also wanted to know if he did any speaking to the boys about parties. He has not got a word to say about that on either side" (Ray Collection, October 21, 1898).

The three soldiers and their young correspondents back in Nebraska are all learning from the experience of war and that experience is valued highly. After the announcement of Willa Cather's Pulitzer Prize in 1923, Ernest Hemingway chastised the woman novelist for the audacity of writing a war novel without having firsthand experience of war: "Look at One of Ours. Prize, big sale, people taking it seriously. You were in the war weren't you? Wasn't that last scene in the lines wonderful? Do you know where it came from? The battle scene in Birth of a Nation [Griffith 1915]. I identified episode after episode. Catherized. Poor woman she had to get her war experience somewhere" (letter to Edmund Wilson, November 23, 1923, qtd. in Baker 105).

Willa Cather used the letters her cousin G.P. sent home from France for a major source of the soldier's life sections of One of Ours (Ray Collection, G.P. Cather letters to wife, Myrtle, and parents, George P. and Frances Smith Cather, January 1916 to May 1918). She even used a senior officer's description of G. P.'s death— which was sent to his parents—in describing the death of her protagonist Claude Wheeler (Ray Collection, letter from M. Morris Andrews, July 5, 1918).

Indeed "she had to get her war experience somewhere," but her sources have more validity than Hemingway gives her credit for. She transcribed war dispatches in Pittsburgh while her cousins studied war in the letters of three Nebraskan volunteers. Such knowledge did not protect G.P. in "the Great War," but then protection is not what he sought. Many reviewers agree with Hemingway and accuse Willa Cather of glorifying war in her picture of Claude's heroic death. Such a reading ignores the final pages of the novel, in which Claude's mother "reads Claude's letters over again and reassures herself; for him the call was clear, the cause was glorious. Never a doubt stained his bright faith. She divines so much that he did not write. She knows what to read into those short flashes of enthusiasm; how fully he must have found his life before he could let himself go so far—he, who was so afraid of being fooled! He died believing his own country better than it is, and France better than any country can ever be. And those were beautiful beliefs to die with" (389-90).

If Claude is under the spell of the glamour of war, his mother is not. She has learned much from his letters. There was just as much information about the nature of any war to be gleaned by youthful G.P. and his brothers in their letters from the war zones. H. C. Gress, the first of this group to be mustered out said it best: "[T]hey can have all the fun they want to, but I have had my fun down there—all I care about anyhow" (Ray Collection, October 15, 1898).

NOTE

The George Cather Ray Collection of letters and memorabilia at the University of Nebraska Love Library offers a multitude of insights into the life of first- and second-generation settlers of Nebraska. While the letters reviewed here are only a small part of the collection, they give much insight into Nebraskans in their time and into the timeless concerns of men and war.

More than twenty of the three men's letters home were preserved, first by the young Cather brothers and later by their mother, Frances Smith Cather.

(Go back.)