From Cather Studies Volume 8

Willa Cather in Paris

The Mystery of a Torn Photograph

Willa Cather recorded her impressions of England and France in travel letters published in the Nebraska State Journal from July to September 1902. Collected in Willa Cather in Europe in 1956, these sketches document her initial encounter with the Old World. Because Cather kept no diary, and few of the personal letters that she wrote in Europe in 1902 survive, scholars have relied upon her journalism for details of the trip she made with Isabelle McClung.[1] Yet there is another compelling record of the journey, one composed not of words but of pictures: a forty-six-leaf scrapbook containing thirty-four photographs. These pictures complement Cather’s published dispatches and offer a more personal view of her first European sojourn than the one she wrote for the public.

Included in the scrapbook are two photographs that were glued in and then ripped in half.[2] In both cases this was done to eliminate the image of someone who had been standing next to Cather. One, taken at the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, invites speculation about Cather’s propensity to manipulate the facts of her biography. As David Porter has documented in three Willa Cather Newsletter pieces, Cather was actively engaged in self-mythologizing and even rewrote her life story for publicity materials and other documents. Does the torn Luxembourg photograph provide further evidence of this self-editing, legacy controlling impulse? Who was the woman standing next to Cather, who excised her image, and why? Before considering these questions, some background on the European scrapbook will provide context.

In addition to the photographs, the scrapbook contains clippings of the Nebraska State Journal articles as well as postcards and other printed pictures from a trip to Italy that Cather and McClung made in 1908. Of the 1902 photographs, three show Cather aboard the SS Westernland on her return trip from Liverpool to Philadelphia, where she arrived on October 4. Two others showing children on canal boats were taken in England, where Cather and McClung remained until the end of July. The rest of the photographs were shot in France. Many of them were taken in the vicinity of the Musée de Cluny, near the pension where Cather stayed at 11 rue de Cluny, and at the village of Barbizon. Some if not all of the pictures were developed in time for Cather to pick up in Paris on 11 August, according to one of her letters (7 August 1902).[3] In addition to Cather and McClung, the photographers most likely included Cather’s friend Dorothy Canfield and a woman named Evelyn Osborne, (more about Osborne below). Both were Cather’s fellow lodgers at the rue de Cluny pensione, which was operated by the mother of Canfield’s longtime friend Celine Sibut.[4] Cather and McClung left Paris for the south of France at the beginning of September.

The provenance of the scrapbook is difficult to establish. Although it was in Cather’s possession at the time of her death, it may have been assembled by McClung (Jewell). This is suggested by the fact that all of the writing on the book’s gray backing paper is in McClung’s hand and that Cather is not known to have kept scrapbooks or photograph albums as an adult. Another possibility, raised by Andrew Jewell, editor of the online Willa Cather Archive, is that the scrapbook was a collaborative effort between Cather and McClung. McClung may have given the book to Cather following the 1908 trip to Italy. It is also possible that she gave the book to Cather later, or that Cather received it after McClung’s death in 1938. Following Cather’s death in 1947, the scrapbook and other worldly belongings were bequeathed to Edith Lewis. When Lewis died twenty-five years later, the book came to one of Cather’s nieces, Helen Cather Southwick, who donated it to the University of Nebraska in May 2001.[5] The leaves were unbound and unnumbered at the time of their accession, and their original order in the scrapbook has yet to be determined. Measuring 6-9/10×9-9/10 inches, the pages were once bound together at the top of the book. The photographs are affixed with glue, with one to three on each side of a page.

Three people—Cather, McClung, and Canfield—were relatively easy for the Willa Cather Archive editorial team to identify when it began to research the photographs in 2003. But there is another woman with Cather and McClung in several of the Paris and Barbizon pictures who escaped identification. Because I had seen a picture of her before and knew her tragic personal history well, I recognized this person—posed in profile with the left side of her face turned away from the camera—to be the aforementioned Evelyn Osborne, who had been so badly disfigured by a burn that stretched from her left eye to the left corner of her mouth that she never allowed that side of her face to be photographed. Indeed, in the other photograph I had seen of her, showing the Barnard College graduating class of 1900, Osborne was the only woman posed in profile.[6]

Cather used Osborne as the prototype for the grotesquely scarred protagonist of her

short story “The Profile” (Madigan 2). Her intention to include the story in her

first collection of short fiction, The Troll Garden, published in 1905, became a point of serious disagreement between her and Canfield,

who was Osborne’s friend. Like Canfield, Osborne was conducting research at the Sorbonne

in the summer of 1902 and pursuing a doctorate in Romance Languages at Columbia University;

it was

Fig. 1. Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace. A woman’s gloved hand can

be seen on the railing. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip

L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University

of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace.

Canfield who arranged for Osborne to board at 11 rue de Cluny, as she also did for

Cather and McClung. When Canfield learned of Cather’s intention to publish “The Profile,”

she pleaded with her not to do so. In a 1 January 1905 letter, she told Cather that

if Osborne were to read the story she would be so upset by the depiction of herself

that she would “never recover.” After Cather refused to withdraw the story, Canfield

protested at the publisher's

Fig. 1. Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace. A woman’s gloved hand can

be seen on the railing. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip

L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University

of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace.

Canfield who arranged for Osborne to board at 11 rue de Cluny, as she also did for

Cather and McClung. When Canfield learned of Cather’s intention to publish “The Profile,”

she pleaded with her not to do so. In a 1 January 1905 letter, she told Cather that

if Osborne were to read the story she would be so upset by the depiction of herself

that she would “never recover.” After Cather refused to withdraw the story, Canfield

protested at the publisher's

Fig. 2. Evelyn Osborne (in profile) and Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France

and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and

Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Evelyn Osborne and Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace.

office; her efforts resulted in the removal of “The Profile” from The Troll Garden. Cather did eventually publish the story in McClure’s, however, following Osborne’s death from appendicitis in 1907. Relations between

Cather and Canfield were strained for nearly fifteen years afterward.

Fig. 2. Evelyn Osborne (in profile) and Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France

and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and

Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Evelyn Osborne and Willa Cather in front of the Luxembourg Palace.

office; her efforts resulted in the removal of “The Profile” from The Troll Garden. Cather did eventually publish the story in McClure’s, however, following Osborne’s death from appendicitis in 1907. Relations between

Cather and Canfield were strained for nearly fifteen years afterward.

The torn Luxembourg photograph is glued onto leaf 7 of the scrapbook (Digital Object Identifier [hereafter doi] 252 on the Willa Cather Archive) (fig. 1). What remains of the picture shows Cather with her right arm resting on a fence rail; a flowering plant and the Luxembourg Palace are behind her. A book, perhaps a Baedeker’s guide to Paris, is held in her gloved left hand.[7] A careful inspection reveals that the figure to Cather’s right was not entirely removed; a black-gloved hand can still be seen resting on the railing. Glue marks on the scrapbook’s backing paper provide telling evidence that the photograph was ripped after it was affixed to the page.

A photograph on leaf 9 offers an intriguing clue as to the possible identity of this woman (doi 254). In it Cather is pictured in the same costume, holding the same book, with the same fence, plant, and palace in the background (fig. 2). Standing next to her is Evelyn Osborne, posed in profile, as always, with the right side of her face toward the camera, a black-gloved hand at her side.

Comparing the torn photograph to this one, it is tempting to conjecture that it was Osborne’s image that was torn away. Given the controversy over “The Profile,” one might surmise that either Cather or McClung wanted to remove the picture of an individual who by that time conjured unpleasant memories. This theory, however, raises vexing questions. Why did the several other photographs in which Osborne appears, including the one left whole on leaf 9, taken soon after or before the one that was ripped in half, apparently not bother Cather or McClung so much? Why was that photograph not torn in similar fashion or left out of the scrapbook altogether?

A plausible answer to these questions is that it was not Osborne but rather McClung

who was excised from the photograph with Cather. If McClung took the photograph of

Osborne and Cather that was left intact, it is possible that Osborne took one of McClung,

who sometimes wore black gloves, standing next to Cather. Support for this theory

comes from the other torn photograph in the scrapbook (doi 485). Glued onto leaf

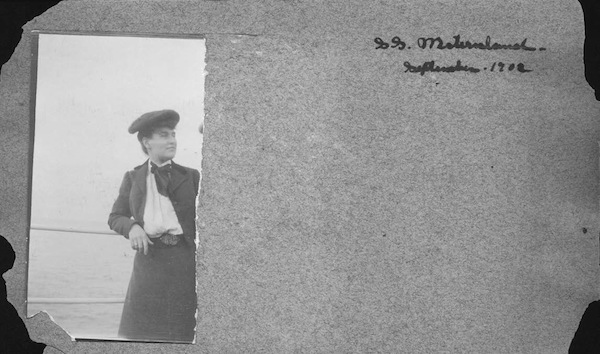

46, this one was taken aboard the SS Westernland during Cather’s return trip to Philadelphia. There, Cather is posed leaning against

a railing on deck, looking at a person standing to her left (fig. 3). The picture

was torn in half to remove the image of this individual, once again after it had been affixed to the scrapbook page.

Fig. 3. Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland. A hat brim is visible on the right side of the torn photograph. Scrapbook of 1902

Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection,

Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland

The identity of the missing person in this photograph may be conclusively determined

by comparing it to another one on the same leaf, which shows Cather, McClung, and

an unidentified young man standing together elsewhere on deck (doi 486). In this

photograph, McClung wears a hat with a brim. A small part of that brim is visible

in the torn photograph, establishing that it was McClung’s image that was ripped away.

Fig. 3. Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland. A hat brim is visible on the right side of the torn photograph. Scrapbook of 1902

Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection,

Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland

The identity of the missing person in this photograph may be conclusively determined

by comparing it to another one on the same leaf, which shows Cather, McClung, and

an unidentified young man standing together elsewhere on deck (doi 486). In this

photograph, McClung wears a hat with a brim. A small part of that brim is visible

in the torn photograph, establishing that it was McClung’s image that was ripped away.

If McClung did remove herself from the photographs at the Luxembourg Gardens and on

board the SS Westernland, one may wonder why she did so. Could it simply have been because she did not like

the way she looked in them? As Jewell has pointed out, she did display self-consciousness

about her appearance when she wrote on the back of a 1923 photograph of herself and

Cather, presumably with irony, “Lovely figger!” (doi 2119). Furthermore, in a picture

of Cather and McClung at Barbizon on leaf 43, McClung’s face is scratched out, perhaps

because she found the image unflattering (doi 476).

Fig. 4. Isabelle McClung, an unidentified man, and Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather

Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Libraries.Isabelle McClung, Willa Cather, an unidentified man aboard the SS Westernland

Fig. 4. Isabelle McClung, an unidentified man, and Willa Cather aboard the SS Westernland. Scrapbook of 1902 Trip to France and Great Britain, Philip L. and Helen Cather

Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Libraries.Isabelle McClung, Willa Cather, an unidentified man aboard the SS Westernland

There are three other scenarios concerning the torn Luxembourg photograph which I will delineate, but ultimately reject. In the first, upon seeing the photograph in Paris, Osborne might have requested of Cather that her likeness be excised from it because it showed the left side of her face. The photographer, most likely McClung, might have caught Osborne off-guard or miscalculated the angle of the shot. The irony inherent in this theory is that Cather later tried hard to publish a thinly veiled depiction of Osborne, replete with disfiguring scar, in “The Profile.”

In the second scenario, too, Cather could have acted according

Fig. 5. Willa Cather and Isabelle McClung at Barbizon. Philip L. and Helen Cather

Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Libraries.Willa Cather and Isabelle McClung at Barbizon.

to Osborne’s wishes. The image of Osborne might have been favorable, and the photograph

torn in half so that she could keep it herself. Perhaps she and Cather even agreed

to reunite the two halves if they were to meet again. What makes both of these scenarios

unlikely, though, is the evidence that the photograph was torn after it was glued into the scrapbook. Since Cather and Osborne never saw each other again

after their time together in Paris, Osborne would not have had an opportunity to see

the Luxembourg photograph in the scrapbook and request that her image be torn out.

Fig. 5. Willa Cather and Isabelle McClung at Barbizon. Philip L. and Helen Cather

Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Libraries.Willa Cather and Isabelle McClung at Barbizon.

to Osborne’s wishes. The image of Osborne might have been favorable, and the photograph

torn in half so that she could keep it herself. Perhaps she and Cather even agreed

to reunite the two halves if they were to meet again. What makes both of these scenarios

unlikely, though, is the evidence that the photograph was torn after it was glued into the scrapbook. Since Cather and Osborne never saw each other again

after their time together in Paris, Osborne would not have had an opportunity to see

the Luxembourg photograph in the scrapbook and request that her image be torn out.

Finally, the third scenario stipulates that it was Edith Lewis who tore the Luxembourg photograph when the scrapbook came into her possession. If it was Osborne who was standing next to Cather, Lewis might have wanted to excise the image of someone associated with a difficult episode in the author’s career. While there is no evidence to rule out this possibility, it does not seem likely that Lewis would have removed only one image of Osborne so long after it was taken and after all of the interested parties were deceased.[8]

In conclusion, I return to the two most plausible hypotheses advanced in this essay. If the woman standing next to Cather in the torn Luxembourg photograph was Evelyn Osborne, and if Cather removed her image, Cather may have felt that while she could not remedy the hurt caused by “The Profile,” she could, at least, eliminate a visible reminder of it. In this case, the photograph testifies to both the degree of pain inflicted by the controversy over the story and Cather’s desire to manipulate her own biography by damaging a piece of documentary evidence. Or does the torn Luxembourg photograph merely evince McClung’s vanity? This explanation is less intriguing but nonetheless layered with irony, for while McClung could easily tear away or scratch out images of herself that she did not like, Osborne could not do so in life or in “The Profile.”

Definitive answers about the torn Luxembourg photograph remain elusive. What can be said with certainty, though, is that the maker or makers of this scrapbook—either Cather or McClung or both—took remarkable care in creating, preserving, and even editing a visual record of the two European trips they made together. The photographs contained therein are an invaluable source of information—and, in some cases, mystery—about their travels.