Cather's Little-Known Friendships

J. R. Henry, the Cumberland Minister

First in a Projected Series

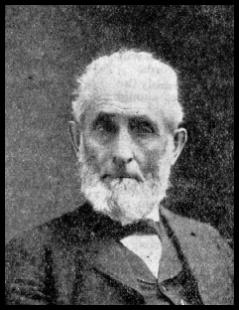

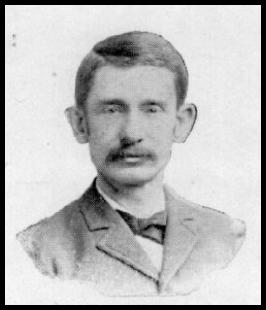

Much of what scholars know about Cather's early career in Pittsburgh comes from four spirited letters she addressed to Mariel and Ellen Gere during July and August 1896, letters that narrate her first encounters with Pittsburgh clergy. As the houseguest of her employer, James W. Axtell, the week of her arrival, Cather was transfixed by the only ornament in the Axtells' parlor, a crayon portrait of Grandpapa Phillip, a Cumberland Presbyterian minister, whose "argus-eyed" gaze seemed to expose Cather as a Bohemian (Woodress 113). In the 1880s, the Rev. Philip Axtell had founded the Shady Avenue Cumberland Presbyterian Church, calling it the "child of his old age" (Gore). The church remained the center of the Axtells' social life; James W. Axtell was an officer in its Sunday School.

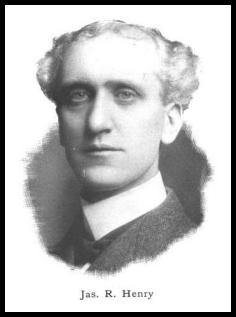

J.R. Henry, the Cumberland Minister,

Image from the Phoenix [Cumberland University, Lebanon TN, 1903], courtesy of the

Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

J.R. Henry, the Cumberland Minister,

Image from the Phoenix [Cumberland University, Lebanon TN, 1903], courtesy of the

Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

A clerical encounter of greater consequence resulted when Cather accompanied the Axtells to Sunday services at the Shady Avenue Church (Woodress 113).[1] In the church's acting minister, the Rev. James Robert Henry, she discovered an intellectual companion and a fellow enthusiast of the arts. In 1896, the year of their meeting, Henry was thirty-one, eight years Cather's senior ("Rev. J. R. Henry").[2] For the next two years, she would frequently call upon Henry as a mentor and escort. As a female correspondent for the Lincoln Courier charged with satirizing the follies of the Pittsburgh elite, she could ask for no better chaperon than a Presbyterian minister. Privately, Henry's sermons were not spared the "meat-ax" criticism of her dramatic reviews. Not long after meeting him, Cather described to Ellen Gere the sermon Henry had delivered the previous Sunday on the text "Whosoever will, let him drink of the water of life freely," her tone conveying the equivalent of a roll of the eyes (Woodress 113, W. C. to E. Gere c. July 27, 1896). But she evidently liked Henry outside the pulpit, for six months later she gave Mariel a triumphant report of her interview with novelist Anthony Hope Hawkins, a meeting arranged by one of her Pittsburgh friends who knew Hawkins at Oxford University. This friend, it turns out, was J. R. Henry (W. C. to M. Gere, 15 Jan. 1898).

Although their friendship has, until now, gone undocumented, Henry is conclusively identified as Cather's benefactor by two documents, the first being the article he wrote for the March 1897 Home Monthly titled "Oxford in Old England" (8-10). The Oxford sketch displays an irreverent sense of humor that his young friend must have found appealing. It opens with a conventional overview of Oxford's location and history, but soon takes a gothic twist: "Under Queen Mary the good Bishops Ridley and Latimer were burnt in the street near Balliol College on October 16, 1555. Three loads of wood and one of futze fagots were consumed in burning them. The total cost of the execution was $6.25" (8). After this extreme example of "roasting," Henry turns to his real topic, "the university and university life in Oxford."

A paragraph on the colleges' administration and faculty stresses the "strict rules and regulations" they impose on undergraduates, then is followed by a series of comic anecdotes about the undergraduates' defiance of college authorities. One such incident Henry claimed to have witnessed personally. As punishment for past misconduct, the faculty of Christ Church College forbade its students to attend a birthday reception for the young Duke of Marlborough, a fellow student known for his extravagant parties. The faculty attended the reception, of course, with their wives and daughters. They had scarcely left campus when the outraged students held "a council of war." Not only did the students decorate the college with red paint (inscribing on the central flagstone, "God Bless the Duke of Marlborough! God d— the Dean!"), but they also purchased two full pages of the Oxford newspaper and filled this space with lampoons of the college faculty. Cather, who had roasted professors she disliked in NU's Hesperian, must have reveled in the Christ Church students' revenge. And she certainly understood the market for anecdotes of the young Marlborough, whose 1895 arranged marriage to American heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt had set tongues wagging on two continents.

The Rev. Philip Axtell, courtesy of the

Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

The Rev. Philip Axtell, courtesy of the

Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

The final page of Henry's article focuses on Oxford's outdoor sports, particularly rowing, and again praises the high spirits of the students, whether competitors or observers. But it ends with two points of criticism that, in his opinion, make American universities superior to their English counterparts. The first is the charade of exams, whose contents were well known to the hired tutors. His second complaint, revealing his advocacy of modern literature, is that the conservatism of the Oxbridge universities had caused their graduate curricula to lag behind that of German and American schools. Only recently, and then reluctantly, he adds, did Oxford adopt a course of study in the English literature and language. Cather, who studied English literature and modern languages at Nebraska, would have agreed with her friend's criticism.

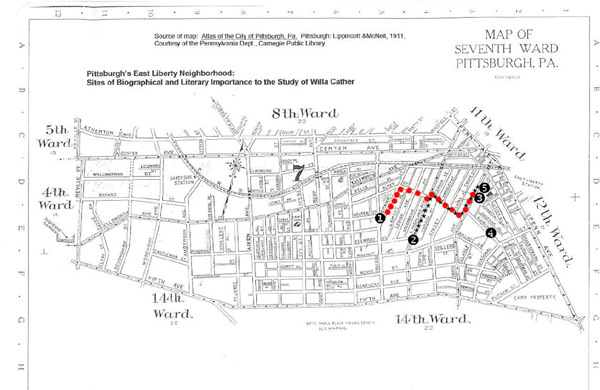

The explication of Henry's friendship forges unexpected links between Cather's fiction, letters, and journalism. Probably unwittingly, Henry served as a model for the minister in "Paul's Case" (conceived November 1902) and in "'A Death in the Desert'" (published January 1903). From April 1894 to 1900, Henry had served as pastor of the Shady Avenue Church at the intersection of Aurelia Street and Shady Avenue in Pittsburgh's East Liberty neighborhood. If Byrne and Snyder are correct in thinking the fictional "Cordelia Street" was based on the real Aurelia Street near the Axtells' home (83-84), then Henry is the logical prototype of the "Cumberland minister," Paul's nemesis, even though Henry resided seven blocks from the church, at 347 Spahr Avenue (Byrne and Snyder 109, n. 8). Corresponding to the Cumberland minister's daughters who discourse with Paul's sisters, Henry had two daughters, Katherine and Lucille, although Henry's marriage date (c. 1885) would make his daughters somewhat younger than the girls in Cather's story ("Rev. James Robert Henry"). Mrs. Henry, the former Annie Butler Satterwaite of Nashville, TN, is the single member of the household spared an appearance in Cather's fiction.

The second piece of evidence documenting the friendship is a four-page autograph letter postmarked June 22, 1897, addressed in Cather's hand to J. R. Henry.[3] When the letter appeared at auction in 2001, Sotheby's offered the following summary in its online and print catalog:

Written at the age of twenty-one [sic—actually 23] telling him how she has been looking for him in vain to bid him farewell, that she will be gone from Pittsburgh for a month, has "finished Gibbon!," and will "carry home many pleasant memories of his kindness."

Publisher James W. Axtell, the Rev. Philip Axtell's son, courtesy of the Historical

Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

Publisher James W. Axtell, the Rev. Philip Axtell's son, courtesy of the Historical

Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

Sotheby's reproduced a photograph of the letter's last page, apparently unaware of the prohibitions in Cather's will. The letter's final page, here paraphrased for legal reasons, says, "She will not forget his kindheartedness; he was her first benefactor in Pittsburgh. She plans to become a member of his Sabbath school class upon her return, with his permission. His manner of living is a credit to Christianity. Good-bye."[4]

The letter's reference to Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire suggests the bicycle-riding minister in "'A Death in the Desert,'" who dutifully stops at the Gaylord ranch to visit Katharine, dying of tuberculosis. Katharine suspects, however, that the minister "disapproves of my profession" and she confides to Everett, "I think he takes for granted that I have a dark past." Katharine is amused by the minister's habit of "trying to patch up my peace with my conscience by suggesting possible noble uses for what he kindly calls my talent" (Collected Short Fiction 205).[5] This passage may be autobiographical, for it seems in keeping with Cather's uncertainty that she will be entirely welcome in Henry's Sunday school class.[6] A few lines later, Katharine concedes, "The parson's not so bad. His English never offends me, and he has read Gibbon's "Decline and Fall," all five volumes, and that's something. Then, he has been to New York, and that's a great deal" (Collected Short Fiction 205).

Image of the former Cumberland Presbyterian Church (photo taken by Tim Bintrim as

it stands today)

Image of the former Cumberland Presbyterian Church (photo taken by Tim Bintrim as

it stands today)

Even if Henry had misgivings about the state of his friend's soul and the propriety of her profession, he was just the sort of scholarly gentleman to have pressed Gibbon on her. He had a solid education, first at the Sumach Seminary in northwest Georgia, then at the Theological School of Cumberland University in Lebanon, TN, where he received a B.D. in 1886. Like the bicycling minister of "'A Death in the Desert,'" Henry had sojourned in New York City, where he completed several graduate courses at Columbia University and attended Union Theological Seminary for one academic year (1892-93). He intended to earn a Master's in Divinity, but was prevented from doing so by financial difficulties and prior commitments to the Synod of Tennessee. When he left UTS, he had completed all the M.D. coursework but not the thesis; consequently, he was awarded a provisional diploma ("Rev. James Robert Henry").

From New York, Henry sailed for England in pursuit of a lifelong dream: studying at a European university. He would have preferred to study in Scotland, but he settled on England, probably again for the sake of economy. In the fall of 1893, he entered Mansfield College in Oxford, England, as a "special student" ("Rev. James Robert Henry"). Mansfield College had moved to the town of Oxford in 1886; it welcomed Nonconformist (i.e., non-Anglican) students from around the world. Cather simplified Henry's situation somewhat by claiming he attended Oxford University. In fact, Mansfield College did not become a part of Oxford University until 1995. Today it boasts of being the smallest, yet most inclusive, of Oxford's forty Colleges ("Mansfield University"). This small, liberal college—within walking distance of Oxford's hallowed halls and libraries, but considerably cheaper to attend—was Henry's home for the academic year 1893-94. Once again, he completed his courses, but not his thesis. During the summer of 1894, he traveled widely in Europe before returning to the United States and a ministry in Pittsburgh ("Rev. James Robert Henry").

When Cather returned to Pittsburgh in the fall of 1897, she may have forgotten her wish to join Henry's Sunday School class, but this was made impractical, anyway, by her following Mrs. Meskimen to a different boardinghouse in Pittsburgh's Oakland neighborhood, near the Carnegie Institute. Later that same fall, when Henry offered to introduce her to Anthony Hope Hawkins, the creator of the fabulously successful The Prisoner of Zenda, she jumped at the chance. Hawkins then ranked among her favorite romantic novelists (W&P 566). By the time she met Hawkins in late October 1897, she had recommended the Prisoner and another collection of Zenda stories, The Heart of the Princess Osra (1895) to readers in Pittsburgh and Lincoln; she also made clear she had read and enjoyed an earlier, light novel called The Dolly Dialogues (W&P 338-39, KA 321).[7] By one estimate, The Prisoner had sold more than 625,000 copies in 1894; by 1897, a stage adaptation by Edward Rose[8] was playing to sold-out houses in New York as well as Pittsburgh (W&P 268). In her book column for the March 1897 Home Monthly, Cather observed that Hawkins's latest novel, Phroso, was crowding out all others in the local bookstores (W&P 342). A week in advance of his appearance in Pittsburgh, Cather had promised her Lincoln readers a view of Mr. Hawkins (W&P 564). Having made this announcement, she must have known her chances for a face-to-face interview were good. Probably Henry had mentioned his literary friend during discussions of his Oxford article, or later, when Pittsburgh learned the novelist would be stopping for several days as part of the Lyceum lecture series.

Surely Cather cherished this chance to talk privately with Hawkins, whose schedule, she knew, was crowded with "supper parties and smokers and other grewsome festivities" (qtd. in W&P 570). First, however, they had to endure a reception of the Writers' Club, a group founded, Cather quipped, "for the express purpose of torturing celebrities" (564). When the formal inquisition ended and the society matrons, reporters, and litterateurs "encircled [Hawkins] between two pots of chrysanthemums," Henry swooped in like one of Hawkins' own heroes to liberate his comrade. Cather wrote, "A clerical friend of mine here attended the same college with Mr. Hawkins, and after the reception carried him off to a private smoking room with me in tow [. . . .] What I wished was to hear the tortured victim [of literary receptions] converse with someone he had known and who cared for him and was not merely trying to pump him" (Lincoln Courier, Nov. 13, 1897; rptd. in W&P 564-70). She observed Hawkins discreetly as he let down his guard:

Mr. Hawkins did not sit still long. He forgot his exhaustion, and putting his arm around his friend's shoulder began to pace the floor and talk of old Oxford days and people, while I sat by the fire effacing myself as nearly as possible. I noticed the serious vein of his conversation, though perhaps that was only natural in meeting an old friend in a strange country. He talked of old dons and tutors, of death and failures, of good fellows who had gone to the bad and bad fellows who had got the prizes of life, until one began to feel rather afraid of living. (W&P 568)

Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins (pseud. Anthony Hope)

in 1895, creator of The Prisoner of Zenda. Photograph from The Bookman 2.3 (Nov. 1895): 175

Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins (pseud. Anthony Hope)

in 1895, creator of The Prisoner of Zenda. Photograph from The Bookman 2.3 (Nov. 1895): 175

Although Cather wrote that her unnamed clerical escort "attended the same college with Mr. Hawkins" she seems to have exaggerated their association. Hawkins' Oxford career is well documented by John Foster's Alumni Oxonienses (vol. 8). Hawkins matriculated at Balliol College on Oct. 18, 1881, aged eighteen; he was a scholarship student 1881-85, receiving his B.A. in 1885, and was an exhibitioner in 1885 (meaning he received some aid as a reward for merit). He received first class honors in a classics examination in 1882 and took his bar at law in the Middle Temple in 1887 (O'Kane). Cather knew at least some of his history, for she insisted Hawkins was "not at all the sort of man for public functions [such as the reception], but rather to live quietly with his pipe in his law chambers in the Temple, making imaginary excursions into Ruritania" (W&P 565).

Henry is not mentioned by name in the Mansfield College General Reports for 1893-94, but these reports do mention "special students" who were admitted as regular members of the College for the academic year: "This year, as in the past, some of the classes have been attended by undergraduates of the University [Oxford], and by students of theology from various parts of the world" (Jenner). The latter group must have included Henry.

Given these dates, it is unlikely that the two men could have been classmates. Between 1881 and 1887, when Hawkins was at Oxford, Henry was studying at Sumach Seminary and Cumberland University. In June 1887, Henry began three years' service to a church in Cleveland, Georgia ("Rev. James Robert Henry"). Instead, the two probably met in 1893-94, during Henry's single year at Mansfield. So while they were not "old friends," it seems plausible that they may have met briefly when Hawkins visited Oxford for an alumni or literary event, or to visit his former tutor. Alternately, Henry may have read and appreciated Hawkins's Dolly Dialogues, and looked up the author at his lodgings, as Cather did in her 1902 quest, with Dorothy Canfield and Isabelle McClung, to meet Shropshire poet A. E. Houseman.

If he was indeed a "bicycling minister," J.R. Henry may have occasionally

yielded the right-of-way to Home Monthly's free-wheeling woman editor

If he was indeed a "bicycling minister," J.R. Henry may have occasionally

yielded the right-of-way to Home Monthly's free-wheeling woman editor

|

Map Key ● ● ● Henry's Commute ★ ★ ★ Cather's Commute

|

Unless his descendents preserved photographs, we may never know for certain if Henry owned a bicycle, but one church history does record that in his later career as a college administrator, "Henry [was] an ardent admirer of athletics, believing that ministers as well as other men should have strong bodies, bright minds, and warm hearts."

If the casual reference in "A Death in the Desert" is, in fact, accurate, Rev. Henry may have gone about his duties on his bicycle, saluting his friend as she wheeled toward her morning's work at Home Monthly. By the end of her first week in Pittsburgh, Cather had left the Axtells' for more congenial lodgings at Mrs. Harriet J. Meskimen's boardinghouse at 309 S. Highland Avenue, just six blocks from the Axtell & Orr offices at 203 Shady Avenue (8). Thereafter the two friends probably met frequently on their "wheels." It is easy to imagine them stopping to chat about their readings, or to discuss the coming activities of the Writers' Club or the fortunes fo Home Monthy.

Despite her ambivalent portraits of ministers in her fiction, Cather must have respected Henry's erudition and enjoyed his company. She probably regretted the loss when he left Pittsburgh in September 1902 to serve the Cumberland University as Dean and Professor of Practical Theology ("Rev. James Robert Henry"), but perhaps after he left Pittsburgh, she also felt more license to depict him in "Paul's Case," a story based loosely on local events of that November. [9] Henry retired from academia in 1906, only to serve a succession of churches as a practical minister. From 1909 to 1914, he returned to the Pittsburgh area to become minister of the Bridgeater Presbyterian Church in Beaver, Pennsylvania. [10] In 1911, Cumberland University awarded him an honorary Doctorate of Divinity, in recognition of his lifelong service to the church ("Rev. James Robert Henry").

When Annie, his wife of almost forty years, died in 1924, she was buried at her birthplace of Nashville, Tennessee. In following years Henry accepted a call to the First Presbyterian Church in Fort Myers, Florida, where he met his second wife, Ruth Weeks. He served the Fort Myers congregation until his death on Feb. 24, 1930. He was buried next to his first wife in Nashville ("Rev. James Robert Henry").

If he were aware of his occasional cameo appearances in Cather's fiction, Henry may have been amused. The allusions are, after all, more teasing than spiteful. It would be only fair if he, too, made occasional light of their friendship in his lectures and sermons, which by all accounts were popular with his congregations and students. On occasion, these sermons may have even impressed a particular "meat-ax young girl" who could not curb her critical faculty, even when in church.

Note of Thanks:

We are grateful to Susan Knight Gore, Archivist and Director of the Historical Foundation

of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church online archive. She repeatedly came through

with the information we needed. We also thank the archivists and librarians at Oxford

University and Mansfield College for their patient responses to our inquiries. We

thank Merrill Skaggs for aiding our research in Drew University's Caspersen Collections,

and Mark Madigan for his critical reading.