McClure's Magazine

by Willa Sibert Cather

From McClure's Magazine, 42 (November 1913): 78-87.

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY

II

IN THE FIRST CHAPTER OF HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY MR. MCCLURE TOLD OF HIS EARLY CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOLING IN IRELAND, THE DEATH OF HIS FATHER, AND OF THE VOYAGE WITH HIS MOTHER AND BROTHERS TO AMERICA. THE FIRST INSTALMENT CONCLUDED WITH HIS REMEMBRANCE OF A FOURTH OF JULY CELEBRATION AT HEBRON, INDIANA, A FEW MILES FROM VALPARAISO, WHERE HIS MOTHER HAD FOUND A HOME

ALTHOUGH my spirits rose so high on that Fourth of July day in Hebron, our arrival in America was the beginning of very hard times for my mother and us boys. We were now almost entirely without money, and were staying with my mother's sister, Mrs. Coleman. Her husband was struggling along on a little rented farm. He had then half a dozen children of his own, was living in a small story-and-a-half frame house, and my two unmarried uncles, Joseph and James, who had come over the year before, were living with him. To have a woman and four children arrive to share these already overcrowded quarters was a serious matter.

Very soon my brother Robert and I were sent to stay with another married sister of my mother, who lived north of Valparaiso, and my mother went to Valparaiso and got a place as servant in a household there. My aunt's husband was having a hard struggle to get along, and he soon became tired of having two extra children quartered upon him. So one day, without warning, he hitched up the wagon and took my brother and me to town and handed us over to mother. My mother was working for the Buell family, living in their house, and when her brother-in-law drove away her position was embarrassing. What to do with her two children she did not know. She could not very well ask the Buells to take us in. Late that afternoon, as evening was coming on, we wandered about the town with her, wondering what we should do. We came to a brick block called the Empire Block, on one of the business streets, which was undergoing repairs and was then unoccupied. Here we found an empty room that was open, and here we spent the night.

IN order to keep us with her, my mother decided to give up her place at the Buells' and do washing by the day. For a dollar a week she rented a room in this same Empire Block, and here we lived, my mother, my youngest brother, and myself. My mother obtained washing and ironing to do in four families; so four days a week she went to the houses of these people, doing all the washing and ironing for a family in one day, and receiving $1.75 for a day's work.

Later Doctor Everts' wife, who had probably heard of my mother's efforts to get along, came to her and told her that she would gladly let her have one of the downstairs corner rooms in her house for herself and her boys, if my mother would do the family washing. This proved a very satisfactory arrangement for us. We were most kindly and hospitably treated in the Everts family. They were extremely considerate of my mother and of us children. Dr. Everts had a large library, and for the first time in my life I found myself in a house where there were plenty of books. I sometimes read two or three books a day. I lay on the carpet, face down, and read for hours at a time. It was then that I first read "Robinson Crusoe."

In that library there were some books about witches and witchcraft which I eagerly devoured. They took possession of my mind and made me so unhappy that I have always felt that such books should be kept away from children. I remember thinking that any one might be a witch in disguise, and wondering whether my own mother were not. I was so nervous that, when some children came in one evening with their faces blacked and grown people's clothes on, I ran screaming into the yard, and could not be quieted for a long while.

BUT these easy times, too, came to an end. The Everts family moved to Indianapolis, and then we found ourselves back in my uncle Coleman's overcrowded story-and-a-half house, fourteen miles south of Valparaiso, with winter coming on. My mother could always get work if it was to be had, and she obtained a place six miles away from the Coleman farm; but she received only two dollars a week, and this was the period immediately following the War, still remembered for the high cost of living. Brown sugar, I remember, went up to twenty-five cents a pound, and gold was at a high premium. I remember the great anxiety about getting shoes for the children. I had gone barefoot as late as possible, like all the other country boys, and delighted to do it; but the time came when shoes were a necessity. My mother managed to get them, somehow. I can remember when she bought me mine, and that they had brass toes. We had not very heavy clothing, and during that winter we children and the Coleman family lived very meagerly. I remember the hardship of having to eat frozen potatoes boiled into a kind of gray mush. I did not thrive on this nourishment. Before the winter was over I had become so weak that my hands were very unsteady and I could not carry a glass of water without spilling it.

HALF a mile west of us lived Thomas Simpson. His farm was the outlying farm of the neighborhood, the one nearest the unoccupied land where the cows grazed. Simpson was a kindly, industrious man from Tyrone, Ireland. He wanted to marry my mother. Clearly something had to be done, and it seemed to mother that when she had this opportunity she ought to marry and give her children a home. She married Thomas Simpson that winter, and Robert and I were taken to his house. The other two boys lived a while with Mr. Simpson's brother, but my brother John came to live with us in March.

There were a hundred acres in the farm, and it was worth about three thousand dollars. At the time of his marriage to my mother Mr. Simpson owed five hundred dollars on it. During the several years that I worked on the place we were never able to reduce the debt. Sometimes we fell behind and owed money to the storekeepers in Hebron.

John and I did the morning and evening chores, which I always hated. The work I liked was cutting wood for the kitchen stove. Our stepfather got his fire-wood from the Kankakee swamp, a great stretch of marshy land to the south of us, of considerable geographical importance in that country. There were wagon-roads through the swamp, and when it was frozen over the settlers took their teams in and felled and hauled away their winter wood. The timber was mostly ash, which is easy wood to split. John and I cut up and split ten logs a day. The logs were about ten feet long and eight inches to a foot in diameter, and each log made six lengths of stove wood. As long as I stayed on the farm I enjoyed this work. Some years later, when I was working my way through college and doing pretty much everything that came to hand, I suddenly turned against wood-sawing. I made up my mind that I had sawed so much wood that, whatever happened, I would never saw any more. And I never have.

THE second winter I attended school for the first time since we came to America. I went to the Hickory Point School, and my Irish speech afforded the boys there a great deal of amusement. The snows were very deep there, and the crust was often so hard that we skated to school, over fields and fences. I was so fond of school that, if I had to work at home for part of the day, I would go all the way to school to get the last hour, from three to four, there.

When I was twelve years old and was still going to that school, I heard somewhere, for the first time in my life, that there was a kind of "arithmetic" in which letters were used instead of figures. I knew at once that I must somehow get hold of this. I asked the teacher, a young man who was then trying to work his way toward a medical school; but, though he had heard of algebra, he had never studied it and had no text-book. There lived not far from us an ex-soldier named McGinley, and I had heard that his wife had been a school-teacher. I went to Mrs. McGinley to ask her advice, and she lent me an algebra. My brother John and I took up this book and went through it as fast as we could, working it out for ourselves and solving the problems as we came to them. We got so excited about it and talked about it so much that my stepfather said he thought he would like to study it, too. He would sit down with us in the evening and work at the problems. But after a little while his zeal flagged and he decided that he could get through the rest of his days without knowing algebra.

During these years the lack of reading matter was one of the deprivations which I felt most keenly. We had no books at home but a bound volume of "Agricultural Reports," sent us by our congressman, and this I read over and over. Then I used to read, with the closest attention, the catalogues sent out by the companies that sold agricultural implements. They seemed absorbingly interesting, and I read them through like books. When I was about thirteen years old I first read, in the weekly edition of the Chicago Tribune, "The Luck of Roaring Camp." It seemed to me a fairly good story about an interesting kind of life. Petroleum V. Nasby, the famous dialect philosopher of that time, I read closely in the weekly paper. It was then I first began to hear of Mark Twain, and to see little extracts from him quoted in the newspapers. It was years before I saw even the outside of one of his books.

I REMEMBER some hunters once camped for the night on our place. I went over to their camp the next morning after they were gone, and found that they had left several old paper-backed novels and a few tattered magazines. These were a great find for me. Years afterward, the idea of forming a newspaper syndicate first came to me through my remembering my hunger, as a boy, for something to read. In the early eighties, when I was working for the Century Magazine in New York, and was going over the files of the St. Nicholas Magazine, I could not help feeling how much I had missed. Here were good stories of adventure, stories of poor boys who had got on, stories of boys who had made collections of insects and butterflies and learned all about them, or who had learned geology by collecting stones and fossils—things that I might have done, myself, if I had known how. It occurred to me that it would be an excellent plan to take a lot of these stories from the old volumes of St. Nicholas and syndicate them among the weekly county newspapers over the country, where they would reach thousands of country boys who would enjoy them as much as I would have if I had had them. I took this plan to Mr. Roswell Smith, of the Century Company. Mr. Smith did not carry out the plan, but the idea of such a syndicate was firmly fixed in my head, and later I was able to carry it out myself.

After I had started my newspaper syndicate, I did manage to get Stevenson and Kipling, Conan Doyle, Stanley Weyman, Quiller-Couch, Stephen Crane, the new writers and the young Idea, to the boys on the farm. I am always meeting young men in business who say: "Stevenson? Oh,yes! I first read 'Treasure Island' in some newspaper or other when l was a boy. It came out in instalments"; or "Why doesn't Quiller-Couch ever write anything as good as 'Dead Man's Rock'? I read that story in the Omaha Bee when I was a kid, and I think it was the best adventure story I ever read. I never got the last chapter. Our paper didn't come that week, and it bothered me till I was a grown man. I finally had to get the book and find out what did happen to Simon Colliver." I believe that my newspaper syndicate did a good deal to awaken in the country boys everywhere an interest in the new writers of that time, and to create for those writers an appreciative audience, besides all the pleasure such stories gave to minds that would have been emptier without them.

THE second summer I spent on my stepfather's farm—I was eleven years old—I did the same work as a man, except where my lack of height was against me. I built the hay on the wagon, for instance, instead of throwing it up from the field, and when the hay was forked from the wagon I built it up on the stack. John and I planted the corn by hand, dropping across the plowed furrows. We cultivated the corn twice, twice down the rows and twice across. When I was twelve and thirteen years old a part of my work was to break the young colts to being ridden.

We all worked hard, but it seemed to me that my mother worked hardest of all. She

got up at five every morning and milked five or six cows. The North of Ireland people

are the best butter-makers in the world, and when butter was bringing twelve and a

half cents at the stores in Hebron, my mother's butter always brought twenty-five

cents a pound and was sent to families in Chicago who had given a standing order for

it. Besides milking and making butter for market, my mother did all the housework,

the cooking and washing and ironing and caring for the children. During the seven

years that my stepfather lived, my mother bore four children, of whom three died in

infancy of enlargement of the spleen. I seem to remember that there was always a sick

baby in the house. About the time the new baby was a few weeks old, the eighteen-months-old

baby would fall sick, and then my mother would have a baby in her arms and a sick

baby in the cradle. She did a great deal of her work

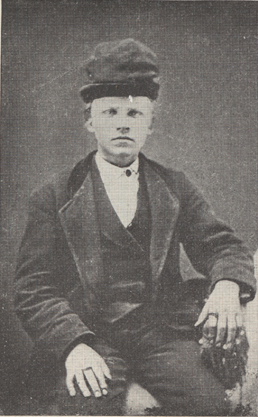

MR. MCCLURE WHEN HE WAS ABOUT THIRTEEN YEARS OLD; FROM A DAGUERREOTYPE OF THE YEAR

HE ENTERED THE VALPARAISO HIGH SCHOOL

with a baby in her arms, and often after being up half the night with the sick one.

I used even then to wonder how she did it.

MR. MCCLURE WHEN HE WAS ABOUT THIRTEEN YEARS OLD; FROM A DAGUERREOTYPE OF THE YEAR

HE ENTERED THE VALPARAISO HIGH SCHOOL

with a baby in her arms, and often after being up half the night with the sick one.

I used even then to wonder how she did it.

MY stepfather was always kind to us. Though physical punishment was then regarded as a necessary thing, especially for boys, he never whipped any of us. He let us work, indeed, harder than growing boys should have been allowed to work, but it was because he knew no better. All our neighbors worked their boys, and my stepfather himself worked very hard. No matter how hard we worked, we could never seem to reduce the debt that we still owed on our farm. The summer that I was fourteen my mother got discouraged. She had always had a fierce desire that her boys should be educated, and my schooling was at a standstill. I had gone as far as I could go in the country school, and had done all the work several times over. I had worked beyond my strength all through the summer of my fourteenth year. Haying was late, and the heavy work came in the very hot weather. I used to drop on the ground from weakness after my work was done, and I suffered so from dysentery that I was unable to sit on the buggy-rake.

One day in September, my mother called me to her and told me that she could not see any chance for me on the farm. If I wanted more education I must manage to get it for myself, and the best thing for me to do was to go away and try. At Valparaiso a new High School was to open that fall, and my mother said she thought I had better go there and see if I could work for my board and go to school. I followed her advice.

I carried with me no clothes except those I had on, and I don't think I took a package

or a bundle of any kind. I had no capital but a dollar and the hopefulness and open-mindedness

of fourteen years. When I came out on a little hill above Valparaiso and looked down

at the

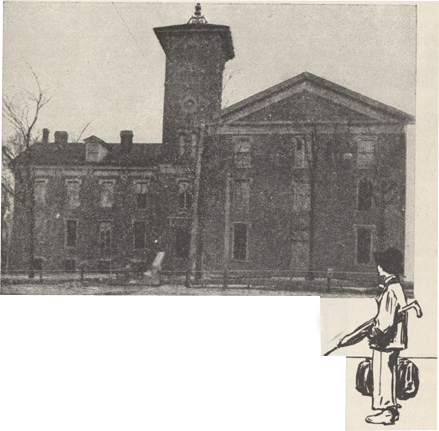

VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY—THE OLD COLLEGE BUILDING AS IT STANDS TO-DAY

white houses and the shady streets, bordered by young maple trees, I had a lift of

heart. It seemed to me the most beautiful place in the world.

VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY—THE OLD COLLEGE BUILDING AS IT STANDS TO-DAY

white houses and the shady streets, bordered by young maple trees, I had a lift of

heart. It seemed to me the most beautiful place in the world.

I WALKED into Valparaiso as fast as I could, and began going from house to house, asking whether anybody wanted a boy to do chores and go to school. It was then late in the afternoon, and I had to get a place to sleep that night. The Everts family, for whom my mother had worked, were then living in Indianapolis; but I went to some of their neighbors. Some one told me that they thought Dr. Cass would take a chore-boy. I knew of Dr. Cass. Indeed, once, when he came to our farm to buy corn, I had computed in my head the cubic contents of a crib for him.

Dr. Cass was then the richest man in all that country. He owned several farms and a good many cattle, and was worth something like $100,000. He was reputed a hard man and was not very well liked. I went to his house and he took me in. There I was called at five every morning, made the fire in four stoves, took care of the cow and the horses, and did part of the marketing before school. In the afternoon I worked on the grounds and did chores until supper-time, and after supper I studied my lessons. Every Monday, however, I was called at one o'clock in the morning to help Ida and Bertha, the two daughters of the house, with the washing. By eight o'clock we would have the washing for the family on the line.

As I have said, there had been no High School in Valparaiso until that year. It was conducted in one large room of the new school building just completed.

After the new pupils were seated, Professon McFetrich came down the aisle, asking each boy to give his full name and say what studies he wanted to take. I was a little nervous, anyway, and it made me more nervous to hear each boy giving three names—John Henry Smith or Edward Thomas Jones. What bothered me was that I had but two names, Samuel McClure, and I didn't want to be conspicuous by having less than the other fellows. I began to rack my brain to supply the deficiency. I had read not long before a subscription history of the Civil War, and had greatly admired the figure of General Sherman. Professor McFetrich was still about six boys away from me, and before he came to my desk I had decided on a middle name. So, when he put his question to me, I replied that my name was Samuel Sherman McClure. Later I changed the Sherman to Sidney. I am usually known now as S. S. McClure, but there never was any S. S. McClure until that morning, and my becoming so was, like most things in my life, entirely accidental.

After he took down my name, the principal began to name over the studies, for me to

say "yes" or "no": Arithmetic, History, Latin, Geography, German, Algebra, Geometry.

To his amusement, I said "yes" to every one of

VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY IN 1871, THE YEAR MR. MCCLURE WENT TO VALPARAISO

them. I did not know what else to do. There was certainly nothing in that list that

I could afford to give up, and it didn't occur to me that I could save any of them

and take them at a later date. During the morning, however, I began to get nervous

about the number of studies I had agreed to take. At noon I went to the principal

and told him that I was afraid I had registered for more subjects than I could do

justice to. He smiled knowingly and said he thought I had. We compromised on a rational

number.

VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY IN 1871, THE YEAR MR. MCCLURE WENT TO VALPARAISO

them. I did not know what else to do. There was certainly nothing in that list that

I could afford to give up, and it didn't occur to me that I could save any of them

and take them at a later date. During the morning, however, I began to get nervous

about the number of studies I had agreed to take. At noon I went to the principal

and told him that I was afraid I had registered for more subjects than I could do

justice to. He smiled knowingly and said he thought I had. We compromised on a rational

number.

I HAD come to Valparaiso run down and worn out with the hard summer on the farm, and the work at Doctor Cass' was not light for a boy of fourteen. Still, I got on pretty well except for the fact that I had no money. I had my board and lodging from Dr. Cass, but not a penny to buy clothes or books. Of course I had no overcoat. I didn't own an overcoat until I was nearly through college. When it was cold—and it was often bitterly cold—I ran. Speed was my overcoat.

I stayed with Dr. Cass through the first term of school, and then I went to spend Christmas with my uncle James Gaston, who had married and then lived four miles north of Valparaiso.

I was not supposed to be away from my chores for more than a day or two, but I had not had a vacation for a long while, and I had such a good time at my uncle's that I overstayed my time. The snow was hard and firm. Sleighing was fine, and there were a lot of friendly young people about. There was one very pretty girl, Helen McCallister, with whom I thought I was very much in love. I certainly enjoyed that vacation. But when I went back to Valparaiso on the first day of January, Dr. Cass refused to take me in again, because I had overstayed my time.

My misfortune, however, was only temporary, and my loss proved to be my gain in the end. I soon heard that Mr. Kellogg wanted a chore-boy. John and Alfred Kellogg were brothers who lived in a double house in Valparaiso and, with a third brother, operated an iron foundry. I went to live with the Alfred Kellogg family, and there I found a home indeed. I at first joyfully characterized the house to myself as a "place with only one cow and one stove." And Mrs. Kellogg was so merciful to the sleep of growing boys that she frequently got up and made that one fire herself. I regret to say that I can remember lying guiltily in bed on a cold morning and hearing her build it. I could never adequately describe the kindness of the Kelloggs.

I finished my first winter at the Valparaiso High School happily enough in the Kellogg family. When the summer vacation came on, it was necessary for me to get something to do. I passed the county examinations, and took charge of a country school two miles north and east of my stepfather's farm. I received fourteen dollars a month and boarded round. I had an opportunity to find out how bad country cooking in America can be, and what outrages can be committed upon good food-stuff.

The custom was then in country schools to keep the little children in their seats

all day,

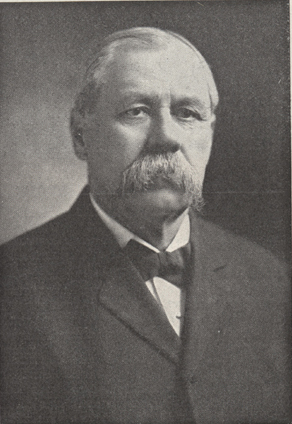

MR. HENRY BAKER BROWN, PRESIDENT OF VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY

although they had only three or four recitations during the school period. This seemed

to me inflicting a needless hardship, so I decided to give the youngest children eight

short recitation periods a day and to let them play out of doors the rest of the time.

The doors and windows of the schoolhouse were always open, and I could keep an eye

on the children just as well as if they were inside, squirming in their seats.

MR. HENRY BAKER BROWN, PRESIDENT OF VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY

although they had only three or four recitations during the school period. This seemed

to me inflicting a needless hardship, so I decided to give the youngest children eight

short recitation periods a day and to let them play out of doors the rest of the time.

The doors and windows of the schoolhouse were always open, and I could keep an eye

on the children just as well as if they were inside, squirming in their seats.

This was not the usual way of managing a country school, however, and a hired man who worked in the fields near the schoolhouse complained to the directors that the new teacher didn't teach the children anything; he was sure of this, because whenever he looked up from his plowing he could see children playing in the yard. I can remember the look of that fellow; he was a big man with a big, brutal face, and for years afterward, whenever I read about bullies or ruffians in novels, they always took on the face of that man.

The school directors met and asked me what I had to say to this charge. I was then fifteen, had had no experience in teaching before, and I was so amazed I hadn't anything to say at all. On the contrary, I put my head down on the desk and cried. But Mr. James Carson, one of my old teachers at the Hickory Point School, spoke up for me, defending my conduct, and the charge was dismissed. I could not, however, teach out my term of three months. The humdrum of teaching was more than I could endure. At the end of two months I quit. One thing I could never do was teach a country school. I tried it twice afterward, but both times I had to run away from the job before the term was over.

THE next winter I went back to Valparaiso to go to school. I stayed with the Kellong's again, but this winter I had to have more clothes and more school-books. I seemed to need more money than I had the winter before, and my school work was interrupted more by the necessity of earning it. I clerked in a grocery store for two months, and for two months I was printer's devil for the proprietor of the Valparaiso Vidette. I learned to set type and make up the paper, but what I most remember was learning to swear. Profanity was then the accepted etiquette about a country newspaper office. The oaths meant nothing. They were not even ingenious or amusing, and they were not indicative of strong feeling. It was simply an ugly habit, like tobacco-chewing—which I got to hate there because the loafers in the office used to spit on the floor about the type-cases, from which I often had to pick up type. I soon became expert in profanity myself, and could scarcely utter a sentence without an oath. When I got over this habit of swearing, I got over it entirely. Ever since it has seemed to me a vice as stupid as it is ugly.

I have always been against using profane expressions in MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE, except where the author could convince me that they were absolutely necessary for the truthful portrayal of character—and then the author had to be some one who knew what he was talking about.

About this time I fell in with Charley Griffith, a lad of my own age who lived with his widowed mother on a hill at the edge of the town. Charley didn't go to school; his eye was too much on the main chance, and he was exceedingly full of shifts. Charley was a great schemer. He was always devising novel and interesting ways to make money. He was never afraid to work, but somehow he never stuck at anything long and he never came out much ahead. Charley's large and adventurous ideas took hold of me right away. Credulity was my native virtue; I beamed with it.

It would take me a long while to enumerate all the ventures upon which Charley and I embarked with proud hopes. I remember at one time we used to borrow horses, ride about the country all night until we could find some one who had an old cow for sale cheap, lead her home, and butcher her in a disused slaughter-house outside the town. Then, after cutting the meat up, we would sell it off a wagon about the town. I can't remember that we ever made much. I don't know what ever made Charley think he could be a butcher, unless it was seeing a perfectly good slaughter-house that nobody was using, and figuring that if only he could be a butcher, he would be ahead a slaughter-house. Charley often figured his profits on a similar basis.

When the summer vacation came on, we decided that it was time we entered business in earnest. I was then sixteen and Charley was about the same age. We went to Westville, a small town about ten miles from Valparaiso, and opened a butcher shop. We started out with a flourishing business, and sold all the meat we could get. It looked a sure thing from the first, and we felt pretty well fixed and had a great sense of dignity. I remember what good breakfasts we used to get at the restaurant near our shop, and with what complacency we ate our pork chops and coffee. But at the end of the month our dream was shattered. We sent out out bills, "dr. to meat for one month," with great satisfaction, but we received few replies. Then we learned that most of our customers were "dead beats," people who owed the other butcher shops so much they couldn't get any meat there. Some of them had not had any meat for a good while, so they had bought it on a generous scale when they had a chance.

Well, now we had no meat and no money. Charley's ardor cooled. We decided that we would employ our talents in other fields. We sold all we had except our team and wagon, and Charley suggested that we drive to Anderson, Indiana, and get a job grading where the Baltimore and Ohio Road was being put through. I was game for that too, so off we went.

But again we were poor calculators, for there were two of us and we had but one team. We got a job on the grade, but there was an extra boy with nothing to do. I drove the team, while Charley tried to get a job carrying water. We worked on the grade for some weeks, and I have forgotten now just why we left it. Probably the elusive goddess beckoned Charley in some other direction.

AS for me, I have never been sorry that I tried and learned something about a good many kinds of work when I was a boy. If I had become a writer when I grew up, such knowledge as I obtained from these experiences would have been of inestimable value to me. The late O. Henry was one of a dozen writers who got their material and their knowledge of people and of the caprices of fortune by knocking about at all kinds of jobs. I am not sure but that, in another way, such experiences were almost as helpful to me as an editor. They made me, I think, more open-minded than I would otherwise have been, and more quick to recognize the young writers who were trying to tell the truth about some phases of American life.

In the fall of '73, when I was sixteen years old, I went back to Valparaiso, and went to work in the Kellogg iron foundry for four dollars a week, living with the Kelloggs again and paying them two dollars a week for board. That was the panic year, and times were so hard that I couldn't manage to start to school at all that fall. Money was so scarce and so hard to make that I became discouraged and began to think of throwing up everything and taking to the road as a tramp.

THE life of a tramp would not have been so distasteful to me as it would to most people. I escaped being a tramp so narrowly that I have always felt that I know exactly what kind of one I should have been. I don't think I should have been unhappy as such. After I left the farm and first went to Valparaiso to go to school, I began to have attacks of restlessness. I simply had to run away for a day, for half a day, for two days. It was not that I wanted to go anywhere in particular, but that I had to go somewhere, that I could not stay another minute.

These fits were apt to come on at any time; but in the spring, when the first warm winds began to blow, then they were sure to come, and to come with a vengeance. There was no standing up against them, and there was no punishment like trying to stand up against them. Usually I didn't try; I simply ran down to the station and took the first freight-car out of town. I rode until I was put off, and then maybe I waited until I could catch another outbound freight and rode some more. Maybe, if the first passing freight happened to be headed for Valparaiso, I jumped on it and rode home. I ran away like this, not once or twice, but dozens and dozens of times. It was a regular irregularity in my life. It was, indeed, more than most other things, a necessity of my life. I could do without a bed, without an overcoat, could go without food for twenty-four hours; but I had to break away and go when I wanted to.

In those days, on each freight-car there were two little platforms about a foot wide, one at each end of the car, where the brake-rod came down. On this little projection I used to sit, with my cap pulled down tight on my head. Of course I preferred to ride on a passenger-train, and I usually managed to get out of Valparaiso on a passenger, resorting to freights to get home. When I rode on the passenger, I made myself at home on the blind end of the baggage-car, winding my woolen comforter close about my neck to protect me from the showers of sparks that blew back from the engine.

This restlessness was something that I seemed to have no control over. I have had to reckon with it all my life, and whatever I have been able to do has been in spite of it. As a lad I followed this impulse blindly, but later I realized that this restlessness was a kind of misfortune, and that it could be at times a hard master. In most things I was fickle and inconsequential, open to any suggestion, ready to quit one job because another was offered, not a very good judge of business propositions, the plaything of casual contacts and chance happenings. But there was one fixed determination, one constant quantity, in my life as a boy—the desire to get an education. That was my one steadiness. Everything else was as it happened. In reality, my runaway trips, my rushing from one job to another, were only apparent ficklenesses. The one thing I really meant to do was to get an education, and in that I never wavered.

IN December of 1873, while I was working at the foundry and wondering what I was going to do next, I received a message from my mother telling me that my stepfather was very ill and I was to return home at once. I went home, and in a few weeks my stepfather died of typhoid fever, leaving the farm to my mother and their one living child. I was mother's oldest son, and there was nothing for me to do then but to stay at home and work the farm for her.

My brother John was then fifteen and my bother Tom thirteen. Robert was still a little fellow. So that winter my two brothers and I undertook to run the farm. In the spring we planted the crops, and that summer we raised and harvested the largest ones that had ever been produced on that farm. In addition, we increased our profits by taking over some marsh-land and making hay on it on shares.

It was while we were working in the hay-field, one day, that there occurred one of those seemingly unimportant events which are often destined to make a great change in people's lives. My brothers and I saw some one coming across the hay-field, and as he approached we recognized my uncle Joseph Gaston, whom we had not seen for several years. He was trying to fit himself for the ministry, and was then attending Knox College, at Galesburg, Illinois. He came up to us in the field, asked us about the farm and how we were getting on with it, and then told us that the thing we must try for was a college education, and that the place to get it was Knox College.

Since I first left the farm to go to school I had meant to get to college somehow; but how I should go, or to what college, was not clear to me. As I listened to my uncle, this vague project instantly became a definite plan. I was going to Knox College. Uncle Joseph talked the matter over with my mother, who required little persuasion. She wanted all her boys to have an education, and, as I was the oldest, it was natural that I should have the first chance.

When September came I set off for Galesburg with eight dollars to pay my carfare, and a heavy black oilcloth valise. Because of this valise my money did not hold out. I took the train at Hebron, and when I arrived in Chicago I had to pay a man fifty cents for hauling me and my big satchel across the city from the Pennsylvania depot to the C. B. & Q. depot. When I went to get my ticket to Galesburg, I found I had not quite enough money left; I hadn't counted on that fifty cents. I bought a ticket to Galva, a town about twenty miles this side of Galesburg, and trusted to luck. I went through all right.

I got off the train with fifteen cents in my pocket. I had on my only suit of clothes, and my mother had made them. The trousers were a good deal too wide and about an inch too short in the leg, and of very stiff cloth. The coat and vest probably had similar faults, but I was most conscious of the trousers. I had on a pair of cowhide boots, and a black felt hat with a droopy brim. I went at once to the campus, and stood looking over the campus and the buildings. I thought I had never seen such fine trees. The afternoon was singularly fresh and clear after a rain, and everything looked wonderful to me.

THERE are few feelings any deeper than those with which a country boy gazes for the first time upon the college that he feels is going to supply all the deficiencies he feels in himself, and fit him to struggle in the world. My preparation had been scanty and I would have to enter the third preparatory year; that meant that it would be three years until I was even a freshman. I was seventeen, and it was a seven years' job that I was starting upon, with fifteen cents in my pocket. I felt complete self-reliance. I had never had any difficulty in making a living, and I knew that I was well able to take care of myself. On the first afternoon, certainly, there was no room in my mind for apprehensions. I could only think about what a beautiful place this was, and that here I was going to learn Latin and Greek.

Once, in Ireland, when I was a little boy, in the Public House at Ballymena I had seen a young priest sitting at a table, reading a book intently. I looked over his shoulder, and, though I could read very well by that time, I could not read a word of that book. I asked him why this was, and he told me that this was Latin. I had never heard of Latin before, but I instantly knew that I wanted to learn to read it, and resolved that one day I would. Now, ten years later, on the other side of the ocean, that day had come.

TO BE CONTINUED