From Cather Studies Volume 10

Introduction

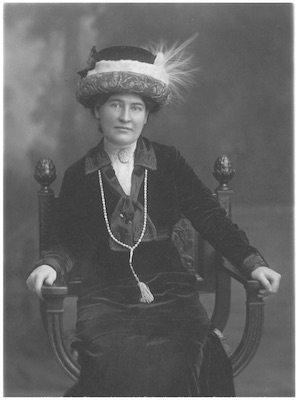

Frontispiece: Willa Cather, studio portrait, wearing a necklace given to her

by Sarah Orne Jewett. Aimee Dupont Studio, New York City, c. 1910. Courtesy

of the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Collection, Nebraska State Historical

Society.

Frontispiece: Willa Cather, studio portrait, wearing a necklace given to her

by Sarah Orne Jewett. Aimee Dupont Studio, New York City, c. 1910. Courtesy

of the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Collection, Nebraska State Historical

Society.

In the well-known studio photograph (c. 1910) that serves as the frontispiece for this volume, Willa Cather appears—to some advantage—wearing a “necklace given to her by Sarah Orne Jewett.” We propose this elegant image, with its implicit acknowledgment of a twentieth-century writer’s bond to a nineteenth-century predecessor, as an emblem of the intellectual enterprise of Cather Studies 10. But the emblem is not a simple one: instructed by a dress historian of our acquaintance, we note that Cather’s outfit—“a brown silk [and] velvet dress with a matching hat trimmed in gold and osprey feathers,” in Mildred Bennett’s description—is thoroughly up to date, a “dressy” afternoon outfit with an especially “stylish” hat. Intriguingly, Jewett’s gift necklace—made of “white jade tinted with pink and green” (Bennett again)—may well be the most fashion-forward part of the ensemble (this style later came to be called a “tango necklace”).[1] We thus glimpse in this arresting image no antiquarian figure, clad in the sartorial vestiges of a lamented Victorian world; rather, Willa Cather has here composed her quite modern image so as to attest to a deep connection to the beloved friend who also figured for her the richness—emotionally, artistically—of nineteenth-century American culture. And it is that act of “composition” we evoke as we introduce the essays in this volume, all of which explore the role of nineteenth-century culture—its writers, artists, and musicians, its cultural formations and forms of feeling—in the making of Cather’s fiction and the shaping of her artistic life.

We also think that our volume, Willa Cather and the Nineteenth Century, has a particularly close and productive affinity with its Cather Studies predecessor, Willa Cather and Modern Cultures (2011), edited by Melissa Homestead and Guy Reynolds. Despite the implications of our dueling titles, that relation is not adversarial but conversational. Indeed, it is the kind of work done by the essays in that volume, which explore, in a specific and textured way, Cather’s complex engagement with an emergent American modernism, that animates this volume’s ambition to explore, with an allied specificity and alertness, the question of how the cultures of the nineteenth century—the cultures that shaped her childhood, animated her education, supplied her artistic models, generated her inordinate ambitions, and gave embodiment to many of her deeply held values—speak in and are spoken to in Cather’s writing.

We have arranged the essays in the volume—all of which had their origin in papers given at the Thirteenth International Willa Cather Seminar, held at Smith College in the summer of 2011—under two rubrics, “Contexts” and “Precursors and Influences.” The distinction is admittedly an inexact one—the works of an artist’s predecessors are certainly among the contexts that enable the meanings of her work—but we use the terms to link essays that propose that Cather learned from, built upon, or resisted models provided by particular writers, works, or genres (“Precursors and Influences”), on the one hand, and those that track the resonances within Cather’s life or writing of cultural formations, emotions, or conflicts of value absorbed from the circumambient atmosphere of her distinct historical moment (“Contexts”).

We begin “Contexts” with a biographical essay that promises to have significant consequences for interpretation. In “Willa Cather, Sarah Orne Jewett, and the Historiography of Lesbian Sexuality,” Melissa Homestead refutes the biographical narrative of a furtive, closeted Cather that has underwritten many significant queer studies readings of Cather’s fiction and of the internal politics of the writer’s life. Applying a detective-like acuity to what had seemed a scanty body of evidence, Homestead demonstrates that the Edith Lewis–Willa Cather relationship was fully acknowledged among friends and family, its significance quite evident in the record left in the undestroyed correspondence. Homestead not only recovers the centrality of this relationship to Cather’s life as a writer; she suggests that Cather and Lewis found, in the nineteenth-century model of female companionship modeled by Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Fields, a way to claim, openly and freely, the power and privileges of their relationship, despite the stigmatizing “medicalization” of homosexuality that looms in the early twentieth-century cultural air.

Charles Johanningsmeier also challenges prevailing critical assumptions and brings nineteenthand twentieth-century literary cultures together in a surprising way in “Cather’s Readers, Traditionalism, and Modern America.” Via a richly specified and powerfully argued exploration of Cather’s collection of letters from ordinary readers, Johanningsmeier questions and complicates—and perhaps even confutes—recent critical claims for Cather’s modernism. In this essay ordinary readers get to add their views to the critical conversation about the value of Cather’s writing, and—by and large—what they treasure in Cather’s fiction are the qualities that link it to the values and pleasures of the nineteenth-century novel and its culture: its implicit critique of a cheapened, materialistic twentieth-century culture; its occasioning of deep emotion in its readers; the authenticity that derives from its compelling verisimilitude; the transparency of its communication of its meanings; the intimacy with the writer herself that reading seems to afford. The essay argues for the value of this quotidian critical tradition in capturing the power of Cather’s fiction—and, because Cather selected and kept these particular letters, proposes that these responses implicitly illuminate Cather’s own commitments as a writer. The figure of Willa Cather that emerges from Johanningsmeier’s study is not simply the Victorian counterpart to the professional critic’s modernist, but a complex, transitional cultural figure, whose achievement is uncontained by the labels conventional literary history has furnished for her.

Leila C. Nadir’s “Time Out of Place: Modernity and the Rise of Environmentalism in Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!” joins Johanningsmeier’s essay in reopening the question of how to locate Cather’s fiction within the transition from a Victorian to a modernist America. Nadir’s rich exploration of Cather’s novel frames the question of Cather’s modernism in terms of a relation to place, thus unsettling both formalistic claims for Cather’s modernism and too simple celebrations or condemnations of her work by ecocritical interpreters. Nadir finds in the novel a powerful critique of the costs of modernization, grounded, like Cather’s “Nebraska” essay, in an evocation of a lost, nineteenth-century relation to land and work; but she also locates, in Cather’s treatment of the characters of Ivar and Alexandra and the relationship between them, the modeling and forecasting of an environmentalism that faces the inevitable fact of development while protecting and sustaining the ethics and emotions that might effectively challenge a mechanized and soulless modernity. For Nadir, then, Cather emerges as a powerful explicator of change, negotiating the dialogue between development and the values it endangers in the context of her own time and providing present-day ecocritics with a clear-seeing, demanding model of environmental engagement.

Our next two essayists place Cather’s fiction in two quite different turn-of-the-century contexts: Progressive Era reform and popular culture. In “Contamination, Modernity, Health, and Art in Edith Wharton and Willa Cather,” Susan Meyer works toward a reading of The Song of the Lark that, like the essays by Johanningsmeier and Nadir, is likely to unsettle more abstract accounts of Cather’s affiliations with modernism. Meyer begins by locating, first in Wharton’s The Custom of the Country and then in Cather’s fiction, resonances of the pure air, pure food, and, especially, pure water reform movements—classic instances of Progressive Era reform. While for both writers, Meyer argues, the sullying of the air, food, and water—particularly in urban environments—focuses anxieties about modernity and its endangerment of the possibilities of an unpolluted art, for Cather, as Meyer tracks the question of purity in The Song of the Lark, the issue emerges with particular complexity. Thea’s endangerment by the despoliation of the urban environments in which her artistic quest inevitably takes place emerges as a strong “antimodernist” current in the text—even as Thea’s health and vigor, confirmed by her sojourn in Panther Canyon, seem to separate her, in an embodied version of modernist artistic estrangement, from the vulnerable and ordinary creatures that surround her. In his essay Steven B. Shively turns to a rich site in American popular culture, the traveling circus (and to a later, related phenomenon, the amusement park), exploring, via an array of texts from throughout her career, Cather’s response to these phenomena. “From Sentimentality to Sex: the Circus Motif in Willa Cather’s Writing” proposes that, while in some works Cather shares the kind of nostalgia for the circus’s appearance in a country town one finds in writers like Howells and Garland, her treatments of the motif, taken together, are much more complex, emphasizing a surprising mix of domesticity, sexuality, and gender breakthroughs via performance. The circus and places like Coney Island’s Dreamland emerge from Cather’s writing as a transformative, layered emotional and cultural site, a rich trope for an emerging modernity.

The two final essays in the “Contexts” section both return to Sapphira and the Slave Girl. In “Daughter of a War Lost, Won, and Evaded: Cather and the Ambiguities of the Civil War,” Janis Stout proposes that we might find the origins of the distinctive complexity of Cather’s fiction—its generative ambivalences, its active and resilient elusiveness, its multiplication of points of view and grounds for judgment—in her childhood experience of the conflicted loyalties that swirled around the question of the moral meanings of the Civil War within her family. A child of the Civil War “borderlands,” situated between Virginia and West Virginia, torn between a Civil War understood as a site of honor and one demystified as a defense of slavery’s brutal exploitations, Cather became in her work an explorer of resonant ambiguities. Stout’s reading of Sapphira and the Slave Girl at once anchors Cather’s treatment of the question of memory in her own historical moment, in which “reconciliationist” views of the war competed with more pointedly accurate memories of its origins in slavery, and opens out into a meditation on the demanding openness—the “enlightened ambivalence”—that shapes her writing more broadly. In “A [Slave] Girl’s Life in Virginia before the War: Willa Cather and Antebellum Nostalgia” John Jacobs builds his reading of Sapphira upon a juxtaposition of Cather’s novel to Letitia Burwell’s A Girl’s Life in Virginia before the War, a text with which it shares a location and some similar narrative materials. Burwell’s 1895 memoir, with its sacrificing, tutelary masters and mistresses and its gratefully subordinate, atavistic slaves, offers a vivid instance of the plantation nostalgia that was a prominent feature of the late nineteenth-century literary and cultural landscape. Cather’s novel emerges from Jacobs’s essay as a rich act of historical imagination, indeed driven by yearning for a childhood past but at once witheringly ironic in its exposure of slavery’s manifold exploitations and deeply complex in its exploration of human character on both sides of the color line.

We commence the volume’s discussion of the “Precursors and Influences” that shaped, enabled, and inspired Cather’s writing by returning to Sarah Orne Jewett, from whom—along with that stylish necklace—Willa Cather received so much. Yet, as with many of the essays in the “Contexts” section, we begin with a resonant complication of what has been the received wisdom. In “Cather’s Jewett: Relationship, Influence, and Representation,” Deborah Carlin, while testifying to the importance of the Cather-Jewett relationship, recasts our understanding of it. She achieves this via an acute reading of the shifts in emphasis in Cather’s representation of Jewett—in letters, in interviews, in her own critical writings about the older writer. The figure of Jewett Cather composes in these texts, Carlin argues, undergoes a subtle shift as Cather’s career unfolds, changing from the adviser and mentor who appears in Cather’s earlier accounts to a diminished, yet internalized figure of the “regional,” nineteenth-century writer Cather is determined—in light of accusations of nostalgia and escapism—not to become.

Carlin’s essay begins a sequence of pieces that explore Cather’s engagement with her American predecessors. Two of the essays—a kind of critical diptych—consider, with a degree of expansiveness new to the subject, Cather’s engagement with the figure and the fiction of Henry James. In “Willa Cather and the Example of Henry James,” Elsa Nettels—choosing her illustrations from a stunning array of works by both writers—moves beyond the notation of obvious instances of influence to describe a tutelage more deeply interfused (to adopt a Jamesian phrasing). She argues that James’s example shaped both Cather’s practice as a novelist—her themes, her experiments with point of view, her plotting, her narrative economy, and her conception of the drama of reading—and her thinking about that process. John J. Murphy, in “Kindred Spirits: Willa Cather and Henry James,” joins Nettels in arguing for a resonant but open conception of the relation between the two writers. Murphy’s essay emphasizes not particular borrowings but a set of generative conceptions or forms of alertness that Cather learned from the older writer: a persistently pictorial quality in her writing that implies a shared sense of the affinity between the arts of the novelist and of the painter; an interest, especially in her own later work, in the depiction of the fully furnished consciousness—itself full of the echoes of its cultural heritage—engaged in this complex work; and, surprisingly, a thematic affinity that reveals both writers to be anchored in an emphatically American issue—the battle between money and meaning.

Our next two essays explore Cather’s use of the fictional models provided by two other American novelists, William Dean Howells and Stephen Crane. The former case is a particularly arresting one, given Cather’s unenthusiastic response to Howells’s version of realism. Provoked by hearing the echo, in The Professor’s House, of a resonant moment from Howells’s The Rise of Silas Lapham, Joseph C. Murphy discovers and explores the surprising relationship between these two novels in “The Rise of Godfrey St. Peter: Cather’s Modernism and the Howellsian Pretext.” Deploying a strikingly innovative conception of “influence,” Murphy demonstrates that elements of Howells’s novel—a middle-aged man, apparently at the apex of career success, the father of two daughters, about to move from one house to another, finds himself in crisis—provided Cather with a set of narrative materials that she reinterpreted with a highly focused freedom, just as St. Peter’s “Christian theologians” recast the materials of the Old Testament, resetting “the stage with more space and mystery.” Murphy’s essay simultaneously puts before us a new way of seeing Cather’s novel and a rich case of her distinctive modernism in action, as she “resets” the work of a realist predecessor. In her essay Ann Moseley puts before us a richly specified instance of Cather’s engagement with Stephen Crane, a writer she unambiguously admired. In “Echoes of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage in Willa Cather’s One of Ours,” Moseley argues for a set of significant affinities between these two novels of young men at war—affinities of narrative stance and style, of elements and strategies of characterization, of thematic emphases and explorations. She finds in both works a resilient ambiguity that suggests that we see these two war novels as engaged in a sustained conversation—with each other and with the questions of development that face their protagonists in the situations battle puts before them.

Our remaining essays take an international turn, testifying to the enduring power English and European artistic models had for this aspiringly cosmopolitan midwesterner—who once remarked, paying tribute to her early education, that “Rome, London, and Paris were serious matters when I went to the South ward school—they were the three principal cities in Nebraska, so to speak” (Selected Letters 105). In “Thackeray’s Henry Esmond and The Virginians: Literary Prototypes for My Mortal Enemy,” Richard Harris simultaneously complicates the critical conversation about the origins of Myra Henshawe and enriches our understanding of the emotional texture and ambitions of My Mortal Enemy—for many readers Cather’s most elusive novel. Harris finds a literary, rather than a real-life, prototype for Myra Henshawe, and for the Myra-Oswald marriage, in characters from Thackeray’s two-novel sequence, Henry Esmond and The Virginians. As Harris sees it, Cather derived her sense of Myra—and the novel’s bleak portrait of a marriage—both from the character Beatrix Esmond and from the sequence’s prominent married couple, Lord and Lady Castlewood. We thus witness, via Harris’s illuminating comparison of these texts, both an instance of Cather’s novelistic tactics, as she transforms and “unfurnishes” a nineteenth-century predecessor, and a demonstration of a particularly productive kind of indebtedness, in which Cather’s mature exploration of character, desire, and marriage is seen to emerge from a conversation with the nineteenth-century novelist she most admired. Robert Thacker’s “‘One Knows It Too Well to Know It Well’: Willa Cather, A. E. Housman, and A Shropshire Lad” tracks the resonances of A. E. Housman’s 1896 volume of poetry in Cather’s life and work. Thacker argues that Cather’s complex and continuing investment in Housman’s volume—and in the conception of the role and purpose of the poet she inferred from it—crucially shaped Cather’s own artistic self-definition. He demonstrates that it operated as a kind of cultural currency as she made her way in literary New York City and—still more significantly—informed the characteristic themes and narrative stances of her richest fiction, most notably The Professor’s House.

In “Following the Lieder: Cather, Schubert, and Lucy Gayheart,” David Porter joins Harris and Thacker in arguing for the generative presence of a precursor artist in one of Cather’s novels, but Porter explores the presence of one of the nineteenth-century expressive forms most important to Cather—as a reviewer, as herself a figure of cultural aspiration and ambition: the century’s music. Focusing on the presence of Schubert in Lucy Gayheart, Porter demonstrates how intensely and variously two Schubert song cycles—Die schone Mullerin and Die Winterreise—permeate the text, enabling Cather not simply to create thematic resonances and ironies but to shape the emotional textures and deeper rhythms of the narrative. As Porter’s essay unfolds, we witness her own innovative novelistic practice and hear, as a kind of overtone, the emotional trajectory of Cather’s own difficult life during the period of the novel’s composition.

The two essays that close the volume maintain the international scope of their immediate predecessors but expand the conception of “precursor” beyond the work of an individual writer or artist or the resonances of any single text. In “Pompeii and the House of the Tragic Poet in A Lost Lady,” Matthew Hokom tracks the implications of a dizzying array of classical allusions embedded in A Lost Lady, thus evoking the power of “the classics” as a versatile cultural currency in nineteenthand early twentieth-century America. Beginning with Cather’s apparently casual evocation of the matter of Pompeii in general and the “House of the Tragic Poet” in particular—a widely known topos in both academic and popular classicism—Hokom argues that classical allusion works not statically but dynamically in Cather’s text, injecting multiple perspectives that complicate our interpretation of Marian Forrester—who emerges as a figure vividly present in the novel but ungraspable by any single perspective. Sarah Stoeckl’s richly conceived “Making It New: O Pioneers! as Modernist Bildungsroman” explores Cather’s relation not to prior writers or texts but to a definitive nineteenth-century novelistic form—the bildungsroman, or novel of development, a canonical expression of the ideologies of self-formation sponsored by Victorian culture. Focusing on the insistent juxtaposition of Marie’s conventional—though tragic—developmental narrative of female “awakening” to the novel’s utterly unorthodox imagining of Alexandra’s emergence, Stoeckl proposes that Cather fulfills the modernist project to “make it new” by radically recasting both the orthodox conceptions of female development and the array of novelistic tactics that had seemed to define those possibilities. Literary form—like the terrain Alexandra herself transforms—emerges from this reading as a kind of imaginative frontier, where the narratives that had seemed to constrain our lives become newly open and generative.

Late in their introduction to Willa Cather and Modern Cultures Homestead and Reynolds suggest that what emerges most compellingly from the essays in their volume is the figure of Cather as a “writer of transition,” an explorer—a sufferer, too—of “the transition into the modern” that unfolded during her era (xix). We think that the essays in this volume, in their attempt to specify and explore the manifold ways that the nineteenth century resonates within Cather’s writing and her artistic and emotional life, share this conception of Cather’s accomplishment. Taken together the two volumes may define with new clarity a capacious and alluringly incomplete question for Cather studies generally: not “Was she a modernist or an elegist?” but “How might we, with sufficient textual specificity and historical alertness, capture the process whereby Willa Cather composed a self, composed a body of work, out of the distinctive materials her changing culture offered to her?” We present the essays in Cather Studies 10 as contributions to and, we hope, generative models for that intellectual enterprise.