From Cather Studies Volume 11

Willa Cather, Howard Pyle, and “The Precious Message of Romance”

In the poem “Dedicatory,” which opens April Twilights, Willa Cather wonderfully evokes the sense of childhood play. The poem, dedicated to her brothers Douglass and Roscoe, recaptures the world of the Cather children’s youth and their “vanished kingdom” “on an island in a western river,” where they and other playmates talked of “war and ocean venture, / Brave with brigandage and sack of cities.”“Wonder tales” they were. These brief lines recall the passage in Alexander’s Bridge in which Bartley Alexander remembers “a group of boys sitting around a little fire . . . on a sandbar in a Western river” (105–6) and, in particular, Cather’s short stories “The Treasure of Far Island” and “The Enchanted Bluff,” in which she describes at much greater length the romantic adventures and “fascinating play world” (“Treasure” 277) of her characters’ and obviously her own youth.

That world clearly owed much to the storytelling and illustrations in the works of Howard Pyle, generally considered the greatest American storyteller and illustrator of children’s books during the late nineteenth century, the period in which young Willa Cather lived in Nebraska, first on the prairie, then in Red Cloud, and finally in Lincoln. Cather mentions Pyle in a January 1897 Home Monthly article, where she comments on his “delightful stories” and describes his works “as some of the best juvenile books published.” She notes that he has not published many works, “for he is not a hack writer, but he writes very much better than men who write more. He is as careful and painstaking and artistic with his children’s books as the very best novelists are with their novels. The Wonder Clock or Salt and Pepper for Young Folks [Pepper and Salt, or Seasoning for Young Folk] cannot fail to make children happy. But best of them all is Pyle’s Otto of the Silver Hand. It is a story of German chivalry in the days of the robber barons” (World and Parish 1: 337).[1]

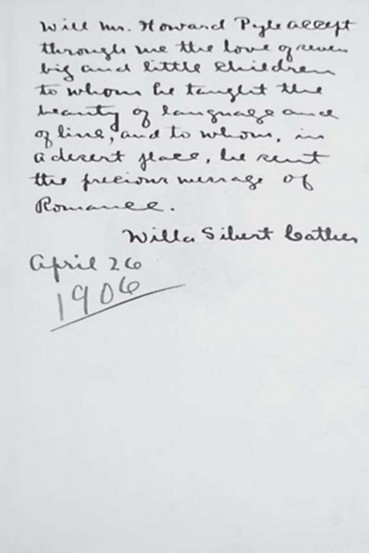

Fig. 4.1. Cather’s inscription to Howard Pyle (1906) in a copy of The Troll Garden. Courtesy of owner of the

volume, Peter Harrington, London.

Fig. 4.1. Cather’s inscription to Howard Pyle (1906) in a copy of The Troll Garden. Courtesy of owner of the

volume, Peter Harrington, London.

Cather, in fact, referred to Pyle’s works throughout her life. For example, in a December 1908 letter to her sister Jessie, Cather describes some British books she has ordered for Jessie’s children as a Christmas gift. She remarks that in only one other case has she seen such beautiful fairy-tale books. According to Cather, these books and the fairy-tale books of Howard Pyle “make all the chromo Maxfield Parrish books in this country just look foolish. The illustrations of people like Parrish and Jessie Willcox Smith,” she says, “are not much better than fancy calendars after all, just chromo faces and stage scenery” (Cather to Mrs. William Auld). In a 1923 letter to Earl and Achsah Brewster, Cather, commenting on the varied reviewers’ reactions to One of Ours, says she understands exactly what the Brewsters had meant when they told Cather that Pyle’s work also had been highly praised by some and dismissed by others (Letters 336–37).

Cather would meet Pyle when she joined the McClure’s staff in April 1906. Her fascination with his works is evident in a copy of the first edition of The Troll Garden that Cather presented to him shortly after she came to McClure’s (fig. 4.1). The inscription reads: “Will Mr. Howard Pyle accept through me the love of seven big and little children to whom he taught the beauty of language and of line, and to whom in a desert place, he sent the precious message of Romance. Willa Sibert Cather, April 26, 1906” (Woodress 51).

Pyle had joined the magazine’s staff shortly before Cather. David Michaelis notes in his biography of Pyle’s most famous student, N. C. Wyeth, that by the early twentieth century,

Magazine and book illustration no longer satisfied Pyle as they once had. Popular tastes were changing. The prestige of medievalism was fading. Picture making had begun to slip from its lofty place in the culture. To apply the term illustration to a canvas seemed all of a sudden to devalue it. At an exhibition of Howard Pyle’s works that winter [1905–6] in Boston, only eight of sixty-three pictures sold. (138)Faced with mounting debt, Pyle was also faced with a decision regarding his reputation: Although Harper’s, which had published his stories and illustrations for years, was still eager to have his works, and had raised the price they were willing to pay for them, Pyle was convinced that the stories by other authors which his pictures often accompanied were generally mediocre and lacked “a permanent literary value” (Michaelis 138).

Enter S. S. McClure, whose magazine staff was in revolt by late 1905 and whose office was in a state of upheaval in early 1906. McClure, in Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes’s words, “lured and McClured” Pyle (qtd. in Kaplan 90), as he also would Cather, signing him to a year’s contract at the unheard salary of $18,000 as art editor of a new publication McClure had in mind. At the time, magazine art editors “generally earned about $8,000 a year” (Michaelis 141).

Pyle accepted the offer but almost immediately began to have second thoughts about the agreement. He was not enthusiastic about working for someone else, especially someone with as strong a personality as S. S. McClure. Also, he was already committed to his painter’s school in Wilmington, Delaware, and he preferred life in Wilmington to life in New York.[2] So Pyle effected a compromise: He came into the McClure’s office three days a week for a salary of $350 per week. This arrangement too proved unsatisfactory, however. Within about six weeks he had decided to quit McClure’s, and on 10 August he resigned the position (Michaelis 140–42, 147–51). Although Cather’s acquaintance with Pyle, it seems, was brief, she nonetheless, even at the age of thirty-two, must have been thrilled to meet the man whose works had contributed so much to her childhood world of play. Her continued admiration and appreciation for his work is obvious from the inscription in The Troll Garden, the numerous references to him in her correspondence, and also in her story “The Treasure of Far Island” (1902).

Almost everyone familiar with Cather’s early life and literary career is aware of the famous passages in My Ántonia in which Jim Burden describes what seemed “an interminable journey across the great midland plain of North America” (3), his “feeling that the world was left behind” (7), and the sense of being “erased, blotted out” (8) by the Nebraska landscape. As Cather’s comments to an interviewer in 1913 indicate, these feelings had been her own, when as nine-year-old girl she had encountered the midwestern prairie for the first time (Bohlke 9–10). Her initial sense of displacement must have been overwhelming at times. In 1905 Cather told Witter Bynner, an office boy at McClure’s, just out of Harvard, that her early years “were pretty much devoted to discovering ugliness” in her surroundings (Letters 88). From the outset, young Willa became aware of many sobering, even gruesome stories associated with the area; in a number of her earlier short stories, barren landscapes and tragic lives are at the center of the narrative. Even in her later, more classically pastoral landscapes, suffering and death are regular visitors or inhabitants, reminding us repeatedly of that pastoral dictum, Et in Arcadia ego.

This was not just any young girl, however. For “Willie” Cather was blessed with an insatiable curiosity and a remarkable sensibility. Having been “thrown out into a country as bare as a piece of sheet iron” (Bohlke 10), encountering a landscape in so many ways wanting the charm and atmosphere of her native Virginia, Cather began to explore the new world in which she found herself. And, of course, she discovered there a different charm, both in the land and in its people, especially the new neighbors—Swedes and Danes, Norwegians, Bohemians—whose customs and conversation she found fascinating. There were various activities in the Cather home and in the homes of friends, and picnics in nearby Garber’s Grove, of which Cather attended fifteen in the summer of 1889 alone (Rosowski 200). And there was the train station; the Burlington Railroad had four trains passing through Red Cloud each day. In many cases the train brought performers to the Red Cloud Opera House, where young Willa and her friends saw many plays and musical performances.

And, of course, there was the land. In that prairie landscape, Cather, brothers Roscoe and Douglass, and several friends found yet another source of excitement and inspiration. This is the world described most fully in “The Treasure of Far Island” and “The Enchanted Bluff,” stories in which Cather is both remembering and “memorializing”—Hermione Lee’s term—her childhood (19). The central setting for both stories is an island in the river near town, which became an enchanted world in a child’s imagination and a cherished place in an older visitor’s or writer’s memory. It is the island of the Sandtown boys of “The Enchanted Bluff” and the Far Island of the story of that name, a “retreat [and] a place of high childish romance” (Brown 40). As Cather tells us in “The Treasure of Far Island,”

Of all the possessions of their childhood’s Wonderland, Far Island had been the dearest. Long before they had set foot upon it the island was the goal of their loftiest ambitions and most delightful imaginings. They had wondered what trees grew there and what delightful spots were hidden away under the matted grapevines. They had even decided that a race of kindly dwarfs must inhabit it and had built up a civilization and historic annals for these imaginary inhabitants, surrounding the sand bar with all the mystery and enchantment which was attributed to certain islands of the sea by the mariners of Greece. (276–77)As Cather’s inscription to Pyle indicates, that childhood “Wonderland” owed much to him. Cather’s mention of a land “inhabited by a race of kindly dwarfs” must have come from her reading of Pyle: many of his Robin Hood and King Arthur stories, as well as his book The Wonder Clock, contain references to dwarfs. Moreover, both the subject matter and the mood described in Pyle’s fiction and illustrations are clearly reflected in “The Treasure of Far Island.” There, for example, Margie, commenting on Douglass Burnham’s great success, notes that he has achieved what he has “as they used to do it in the fairy tales, without soiling your golden armor” (273).[3]

By the time Cather was ten years old, Pyle had already established himself as an illustrator of note. His earliest works, illustrated animal fables and fairy tales, appeared regularly in Scribner’s and St. Nicholas in the mid-1870s. These were genres he would continue to explore. By the late 1870s Pyle had established himself with stories and illustrations in Harper’s and had become very successful. By the early 1880s he had become a household name (Abbott 101).[4] He is considered by many art historians to have been the major influence in what is known as the Golden Age of American illustration, roughly 1880 to 1920. The Wonder Clock, for example, originally published in 1888, was one of his most successful works. A collection of twenty-four fairy tales, each accompanied by a poem and an illustration, the volume was an immediate success and would remain so popular that thirty years later it sold six times as many copies as it had upon its original publication (Abbott 108). In addition, Pyle’s works are quite clever and are marked by an appealing sense of humor. “I try to make them as witty as I can,” Pyle said (Abbott 35). Pyle’s appealing writing style in concert with his remarkable illustrations made his books irresistible to children. His attempts “to indoctrinate a small lesson” (Abbott 35), to include advice about common sense and good behavior, no doubt won parents’ approval as well.[5] Pepper and Salt, or Seasoning for Young Folk (1885), a collection of eight stories written and illustrated by Pyle and twenty-four poems each also with an accompanying illustration, is representative of this type of work by Pyle.

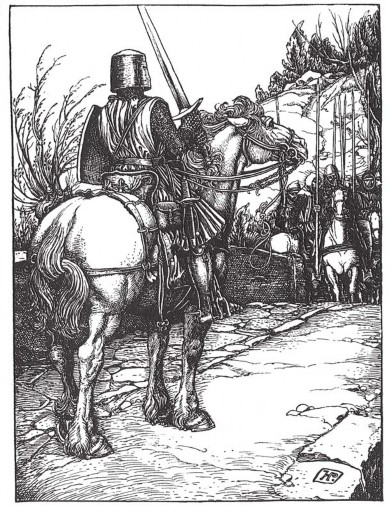

Fig. 4.2. Howard Pyle, illustration from Otto of

the Silver Hand, 1888.

Fig. 4.2. Howard Pyle, illustration from Otto of

the Silver Hand, 1888.

The breakthrough work in Pyle’s career, however, was The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, published in 1883, the same year that Charles Cather moved his family from Virginia to Nebraska. Pyle began considering such a volume in 1876. He wrote to his mother on 30 November of that year, “I have been thinking lately that stories from the life of Robin Hood might be an interesting thing for St. Nicholas. Children are very apt to know of Robin Hood without any very clear ideas upon his particular adventures. And then how gloriously they would illustrate” (Abbott 31). It was Pyle who first organized the Robin Hood tales into a coherent narrative and made the borderline criminal into the heroic figure we think of today. As Pyle’s earliest biographer remarks, “Robin Hood, Little John, Friar Tuck, Will Scarlet, all are intensely human personages, yet all move in an atmosphere that is brimming with fanciful notions” (Abbott 113).

Pyle's Merry Adventures of Robin Hood was an immediate success. Mark Twain called Pyle’s edition “the best Robin Hood that was ever written” (qtd. in Michaelis 35), and in the opinion of many, after more than 130 years, it remains the best edition of the Robin Hood stories ever published. Twain insisted that Pyle was the only person who should do the illustrations for his version of the story of Joan of Arc. Frederic Remington was so impressed with Pyle’s painting “Pirates Used to Do That to Their Captains Now and Then,” which appeared in Harper’s Monthly in November 1894, that he wrote Pyle asking to trade works for it and telling Pyle that he could take anything in his studio in exchange (Abbott 145). The noted American artist Joseph Pennell compared Pyle’s illustrations in Otto of the Silver Hand to those of Albrecht Dürer (Abbott 117).

Admiration for Pyle’s work was not limited to the United States, however. In England, William Morris, who himself had done so much to re-create the world of the Middle Ages, had nothing but praise for Pyle’s stories and illustrations. In 1882, twenty-nine-yearold Vincent van Gogh asked his brother Theo, “Do you know an American magazine called Harper’s Monthly? There are wonderful sketches in it . . . things in it which strike me dumb with admiration,” and he noted, in particular, drawings by Howard Pyle (van Gogh 1: 453). Van Gogh also mentions Pyle in several letters to artist friend Anton Ridder van Rappard, praising Pyle and some other illustrators as “great black-and-white artists of the people” and declaring one of Pyle’s illustrations “a damned fine thing” (3: 329, 382). Van Gogh, in fact, was so impressed with Pyle’s artistry that he collected the two-page tearsheets of Pyle’s illustrations printed in Harper’s.

Pyle’s books, published by Harper and Brothers, are visually beautiful, a characteristic that Cather later found so appealing about the books that Alfred Knopf produced. In addition to the illustrations, Pyle’s writing style in these works is “a very successful adaptation of archaic English, not so complex as to be hard to read, but sufficiently antique to lend the charm of age to the narrative” (Abbott 114). Pyle’s ingenious “re-creation” of a sort of “older” English is an element of his writing that Cather specifically noted in her inscription in The Troll Garden, where she refers to the “beauty of language” in his works.

While Cather might have encountered any number of Pyle’s illustrated fairy tales or his illustrations on American history, his works set in the Middle Ages and the series of stories and illustrations having to do with pirates clearly were at the heart of the imaginative worlds young Willie Cather and her brothers created. As one writer assessing Pyle’s career said in 1907, “The culture of the imagination is a vital part of Mr. Pyle’s theory” (Trimble 459). It was the child’s and adolescent’s imagination (and those of any number of “big children” as well) that Pyle knew so well and appealed to so effectively.

So, on the one hand, what better subject exists for stories and illustrations for young people than the Middle Ages, with its stereotypical knights and fair maidens, its examples of chivalry and romance and adventure? Pyle’s four volumes on King Arthur, previously created stories collected and published between 1902 and 1910, captured both in text and in pictures that magical, heroic world. Cather’s favorite, as noted, was Pyle’s second medieval book, Otto of the Silver Hand, published in 1888 (fig. 4.2, p. 100). It is a tale of a different sort, providing, according to Cather’s 1897 Home Monthly article,“a very fair idea of what that phrase ‘the Middle Ages’ meant” (World and Parish 1: 337). Pyle’s story begins with an indication of his didactic intention: “This tale that I am about to tell is of a little boy who lived and suffered in those dark middle ages; of how he saw both the good and the bad of men, and of how, by gentleness and love and not by strife and hatred, he came at last to stand above other men and to be looked up to by all” (2). Set in medieval Germany, Otto of the Silver Hand traces the adventures of a young boy as he encounters the world at large for the first time. In this respect the novel is both romantic tale and disturbing bildungsroman.

Young Otto, the son of a brutal German robber baron, becomes witness to his father’s ruthlessness, especially in his rivalry with another baron. In the course of various intrigues, Otto is captured by the rival baron and imprisoned in the enemy castle, where the rival baron has Otto’s right hand cut off.[6] During an exciting rescue, Otto’s father dies valiantly in single combat with the evil knight, holding his position on a bridge so his son and comrades can escape. (In that battle Otto’s father, of course, kills the rival baron.) The good and just Otto eventually ends up meeting Emperor Rudolph, who takes Otto into his court. Otto subsequently marries a sweet young maiden named Pauline and establishes a new regime as the baron of the castle of Drachenhausen. His missing right hand is replaced with a hand made of silver, and the new motto of Drachenhausen becomes, “A silver hand is better than an iron hand.”

As was noted earlier, Cather’s fascination with this book remained strong throughout her life. One of the more interesting references to Otto appears in a 1941 letter to Roscoe in which Cather mentions the recurring problem with her right hand. (We should remember that this letter was written about fifty years after Cather had likely first read Pyle’s novel.) Her surgeon, she says, had tried to convince her to give up writing by hand and to compose simply by dictating, something, Cather declares,“absolutely impossible to me and against all my taste and habits.” So the Knopf office contacted Dr. Frank Ober, a hand specialist in Boston, who constructed a metal forearm and hand brace for her. Cather concludes the letter to Roscoe with the comment, “You know, with my metal glove, I feel just like Otto of the Silver Hand!” (Letters 599–600).

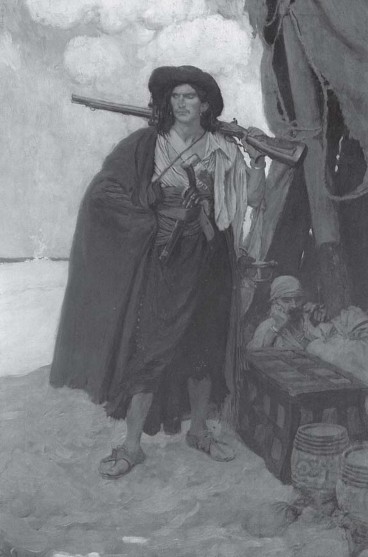

Fig. 4.3. Howard Pyle, “The buccaneer was a picturesque fellow.”

Source: Howard Pyle, The Fate of Treasure

Town, published in Harper’s Monthly

Magazine, December 1905.

Fig. 4.3. Howard Pyle, “The buccaneer was a picturesque fellow.”

Source: Howard Pyle, The Fate of Treasure

Town, published in Harper’s Monthly

Magazine, December 1905.

Despite the obvious moral or ethical foundation of his stories and the seriousness of works like Otto of the Silver Hand, Pyle remarked in a letter to a reader that his works were not for those “who plod so amid serious things” that they are reluctant to give themselves over to the “land of fancy” he creates. Both as a writer and an illustrator, he declares, he “lift[s] the curtain that hangs between here and No-man’s-land” and invites the reader to follow him into the imaginative world he creates (qtd. in Abbott 112–13). Some years later, of course, the term “no-man’s-land” would come to have a much different meaning. However, Pyle’s use of the term here and elsewhere is interesting: that is exactly the term Cather uses to describe Far Island in her 1902 story (“Treasure” 265).

As “The Treasure of Far Island” opens, Douglass Burnham returns after a twelve-year absence to the midwestern town where he grew up. (Cather here, of course, uses the name of her own brother.) The boy, who had been “the original discoverer” of Far Island, now twenty-seven and a celebrated New York playwright, is reunited with his childhood friend Margie, with whom he reminisces about the times they had shared on the enchanted island. Although the story’s rather sentimental ending compromises the narrative somewhat, Cather’s description of the world they had shared is nonetheless very effective. The details she provides in the story are clearly based on actual memories as well as material from children’s books and other literature. More specifically, the story is invested throughout with the kind of romance found in the worlds of knights and especially pirates created by Howard Pyle.

As Pyle’s biographer Charles D. Abbott noted in 1925, “Pirates and their adventures held a strange attraction for him; he was never more content than when he found some half-forgotten account of a notorious buccaneer, and had plenty of time to spend in an examination of it” (132). Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (a book that Cather praised highly) appeared in 1883, but it was Pyle who defined and popularized the pirate not only for his generation but for ours as well. Pyle took the generally crude and villainous character of history, transformed him enough so that he appealed to many fascinated by what has been called a sense of “the masculine primitive” (Loechle 62–63), and created a literary type whose adventures often seemed heroic, even if his actions outside the law often led to sad consequences. The swashbuckling heroes of the Douglas Fairbanks and Errol Flynn movies of the 1920s and 1930s, as well as the pirate captain of the Johnny Depp/Jack Sparrow movies of today, basically owe their creation and costuming to Pyle’s figures of over a century ago.

Pyle’s first major achievements in this genre were the short story “Rose of Paradise,” which appeared in the 23 July 1887 Harper’s Weekly, and a two-part article titled “Buccaneers and Marooners of the Spanish Main,” which appeared in Harper’s Monthly in August and September of that year. The illustrations for these works were considered “epoch-making” (Abbott 141), especially the picture titled “Marooned,” which brilliantly captures the utter despair of a pirate sitting on a beach, resigned to his fate. Other stories were published in Harper’s magazines throughout the 1890s and in the first decade of the twentieth century, and were included in various book-length volumes thereafter. Important novel-length stories of pirates by Pyle were also published between roughly 1890 and 1910. Ten years after Pyle’s death in 1911, his seven pirate stories were collected and published by Harper and Brothers, with copies of the original illustrations, under the title Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates (fig. 4.3, p. 104). A review of the publication of a collection of pirate stories titled “The Rose of Paradise” clearly acknowledges the appeal of Pyle’s works to readers both younger and older. The reviewer praises the “exceedingly spirited” narrative of the story, then adds, “The book is one that boys will be apt to read with eagerness, and which we are disposed to recommend as wholesome reading for them, and which will not be despised by the grown-up men who have not outgrown their liking for the kind of literature which they best enjoyed when they were boys” (Literary News 334).

More than any other Cather short story, “The Treasure of Far Island” recounts the child’s or adolescent’s imaginative sense of romance and adventure, and makes clear Cather’s debt to Pyle’s medieval and pirate fictions and illustrations. As in Pyle’s tales, Cather’s story is filled with names of exotic settings—Far Island, Silvery Beaches, Glass Hill, Salt Marshes, Huge Fallen Tree, The Uttermost Desert—and is peopled with “kindly dwarfs,” pirate chiefs, “gallant lads,” and even “a captive princess.” And it is filled with other paraphernalia of medieval and pirate romances. In the buried treasure rediscovered by Douglass and Margie near “the bleached skeleton of a tree” with a cross “hacked upon it,” there is a “manuscript written in blood, a confession of fantastic crimes, and the Spaniard’s heart in a bottle of alcohol, and Temp’s Confederate bank notes . . . Pagie’s rare tobacco tags . . . and poor Shorty’s bars of tinfoil” (279–80). There is a silver ring that had belonged to Douglass’s father, but which in the world of childhood romance had been “given to a Christian knight by an English queen, and when he was slain before Jerusalem a Saracen took it and we killed the Saracen in the desert and cut off his finger to get the ring” (280). In addition, this had been a world of swords (a butcher knife stuck in young Pirate Chief Douglass’s belt), intriguing markings and messages on a faded treasure map, and a boat named the Jolly Roger. “Wild imaginings”—Cather’s phrase—these had been (280). Despite Margie’s reference to Douglass’s “golden armor” and the reference to the Crusades, the childhood world of “The Treasure of Far Island” is not so much that of the knight and “enchanted princess” (“Treasure” 273) but rather of pirate adventurers. Cather, in fact, uses the words “pirate” or “pirates” seven times in the story.[7]

Willa Cather, of course, would move on from that childhood world of imagination and adventure that was such an important part of her youth. However, Sandy Point, the imaginary town she and her brothers Douglass and Roscoe created, remained an essential part of her memory and an important reference point for the rest of her life.[8] Writing Roscoe from Venice on 16 July 1908, Cather declared, “Here at last is a place as beautiful as Sandy Point ever was in the days of its pride and power.” In a letter to Roscoe on 13 February 1910, she again mentioned Sandy Point, describing her work as managing editor at McClure’s as a “harder job to boss than Sandy Point” (Letters 130). (Young Willa Cather had been elected mayor of Sandy Point.) On 8 July 1916, as what would become My Ántonia began to take shape in her mind, Cather told Roscoe that she “didn’t seem to have acquired a single new idea since Sandy Point” (Letters 226).

Sandy Point was more than a mere memory or creative reference point for Cather, however. It was an emotionally charged ground of her being. “Art,” she says in The Song of the Lark, “is only a way of remembering youth” (506). Writing to Irene Miner Weisz in early 1931, Cather again recalled her happy childhood and commented, “I want someone from Sandy Point to go along with me to the end” (Letters 442). Her childhood friend Jim Yeiser, a comrade who also never forgot Sandy Point, in a sense did just that. Answering a letter from Cather only weeks before her death—over half a century after their adventures at Sandy Point—he wrote from San Francisco that thinking about those days long ago made him homesick, and he concluded, “Remember, Willa, if there is anything more I can ever do let me know. The founder and mayor of Sandy Point always will receive prompt attention.” Those childhood experiences and the child’s love of play remained dear to all of those who had played at Sandy Point and had read tales of adventure and intrigue—“wonder tales,” as Cather called them in “Dedicatory.”

When the mature Willa Cather looked back on her childhood in Nebraska, she fondly remembered the transforming power of a child’s imagination, which could create a world unto itself. Cather’s early reading of Pyle and others always lay at the heart of her memories of that period in her life. One of the other books she read early on was George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. In an “Old Books and New” column written for Home Monthly in November 1897, Cather described Tom and Maggie Tulliver as “two wonderful figures which have never been surpassed in English fiction,” and remarked,“I wonder why it is that no one else has ever been so successful in painting that strongest and most satisfactory relation of human life, the love that sometimes exists between a brother and sister, a boy and a girl who have laughed and sorrowed and learned the world together from the first. . . . When you have travelled the wide earth over and seen the beauties of all lands and seas, what spot is it that your heart cries out for with unassuaged longing but the spot, no matter where, no matter how desolate, where you have been good and happy and a child!” (World and Parish 1: 363–64).[9] The goodness and happiness of Willa Cather’s childhood owed much to the actual settings and people and circumstances of her life, but also to her reading, and to the fascination with the magical worlds of knights and pirates, of heroes and villains, of adventure and intrigue that she discovered in the works of Howard Pyle, and through her youthful imagination re-created with her brothers and friends “on an island in a western river.”[10]

NOTES

Lift high the cup of Old Romance, And let us drain it to the lees; Forgotten be the lies of life, For these are its realities.The complete typescript copy of the poem is in the Helen Cather Southwick Collection of the Willa Cather Foundation; the poem, published without the first three stanzas, can be found in April Twilights (69). (Go back.)