From Cather Studies Volume 11

Willa Cather, Ernest L. Blumenschein, and “The Painting of Tomorrow”

Willa Cather was both enamored of and inspired by the region, people, and culture of the American Southwest. Scholars have had a lot to say about her relationship to this region, but even so, gaps remain. One unexplored aspect of Cather’s Southwest experiences is her relationship with the modernist American painter Ernest L. Blumenschein. Born in Pittsburgh and raised in Dayton, Ohio, Blumenschein began his career illustrating works by Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane, and Jack London for such publications as Century, McClure’s, and Harper’s. In 1907, Blumenschein provided the illustrations for Cather’s third story in McClure’s, “The Namesake.” He and his wife, the painter Mary Greene Blumenschein, were friends of Cather and Edith Lewis, and while their names do not appear in the biographies of Cather by Bennett, Lee, or Woodress, Blumenschein’s work and theories of art are an important presence in Cather’s fiction, specifically in “Coming, Aphrodite!” and Death Comes for the Archbishop. In “Coming, Aphrodite!” Cather bases the character of Don Hedger at least in part on Blumenschein. In addition to biographical similarities, Hedger’s work depicting Native American customs and his theories of modern art are quite similar to Blumenschein’s work and published writings. In Archbishop, several of Cather’s descriptions bear a visual and thematic similarity to three of Blumenschein’s modernist landscapes from the 1920s. I hope here to shed new light on Cather’s friendship with the painter, her developing ideas related to modern art, and her use of modernist techniques in Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Ernest Leonard Blumenschein was born on 26 May 1874. His family moved to Ohio in 1878 after his father was hired to conduct the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra, and after his mother’s death in 1881 the young Ernest took up the violin. He became a concert violinist at the age of seventeen, but it was art and illustration that inspired him. In 1891 he received a scholarship for violin to the Music Academy of Cincinnati, but after one year, and against his father’s wishes, he transferred to the city’s Art Academy. In 1893 he studied at the New York Art Students League, and in 1894 at the Académie Julian in Paris. In 1896 he returned to New York to work as an illustrator, and in early 1898 he made his first trip to Arizona and New Mexico. Later that spring, he convinced friend and fellow painter Bert Phillips to join him on a second journey west, and after several months painting in Colorado, the two headed to New Mexico. During this leg of their trip, one of their wagon wheels broke, and Blumenschein took the wheel to be repaired in nearby Taos, New Mexico. This journey would be the inspiration for much of his later work and career. As he walked the twentytwo miles to Taos, Blumenschein was inspired by what he saw. In his essay “The Broken Wagon Wheel: Symbol of Taos Art Colony,” published in the Santa Fe New Mexican on 26 June 1940, Blumenschein writes: “No artist had ever recorded the superb New Mexico I was now seeing. No writer had, to my knowledge, ever written down the smell of this sage-brush air, or the feel of the morning sky. I was receiving, under rather painful circumstances, the first great unforgettable inspiration of my life.” Blumenschein stayed in Taos for three months and then returned to New York to resume his work as an illustrator of popular magazines and books. Beginning in 1910 he spent his summers in Taos, and in 1915, he along with several others founded the Taos Society of Artists.[1] In 1920 he moved his family permanently to Taos and was finally able to give up illustrating and focus on painting. During his lifetime, Blumenschein was the best known of all the Taos painters and received numerous honors and awards during his career. His work embraces impressionist and post-impressionist techniques, including the focus on the changing nature of light and shadow, the abstract rendering of the natural world, and the use of vivid colors. Today his work hangs in many of the world’s greatest galleries.

We are not exactly sure when Cather and Blumenschein met, but in a letter to Ferris Greenslet dated 13 September 1915, Cather writes, “Miss Lewis and I met several old friends in the artist colony at Taos, among them Herbert Dunton[2] and Blumenschein” (Letters 208). During Cather’s time at McClure’s, Blumenschein provided several illustrations for the magazine; for example, in the May 1907 issue he illustrated a story by Michael Williams titled “A Fight in One Round.” Also, Blumenschein’s wife, Mary Greene Blumenschein, herself an accomplished artist, was interviewed in the 10 May 1915 edition of Every Week, possibly by Edith Lewis (“Mrs. Blumenschein”). In his 1947 notes for an autobiography never written, Blumenschein lists Cather as one of the persons he would “sketch” (“Ernest Blumenschein Papers”). There are numerous other biographical connections, including common friends such as Mary Austin, Mabel Dodge, and her husband, Tony Luhan, but the first confirmed professional connection between Blumenschein and Cather, as mentioned, are the two illustrations Blumenschein provided for Cather’s story “The Namesake” in the March 1907 McClure’s. The first, “Lyon,” depicts a young man, presumably the title character, gazing absently into the distance. The second, “Despite the Dullness of the Light, We Instantly Recognized the Boy of Hartwell’s ‘Color Sergeant,’” is based upon Henri Fantin-Latour’s famous painting A Studio in the Batignolles, a portrait of Édouard Manet’s studio that includes Monet, Renoir, and Zola among others gathered around the great Manet. Similarly, Blumenschein’s illustration shows a group of artists gathered around the sculptor Lyon Hartwell, who is discussing his inspiration and namesake, his uncle who died during the Civil War. When the story was being prepared for publication in late 1906 and early 1907, Blumenschein was in Paris and the Fantin-Latour painting at the Musée de Luxemborg. Blumenschein probably had permission to copy it (Duryea 81). Cather most likely had seen the Fantin-Latour painting during her visit to Paris in 1902, and we can imagine she was greatly pleased with Blumenschein’s illustration paralleling her story of Hartwell with the great Manet.

Cather’s 1920 story “Coming, Aphrodite!” presents another connection between Cather and Blumenschein. Although the prototype for the painter Don Hedger has never been positively identified, a number of biographical and artistic similarities point to Blumenschein. In addition to several biographical parallels between Hedger and Blumenschein,[3] Hedger, like Blumenschein, has “been a good deal” in the Southwest and paints the people and culture of the region. Both experiment with subject and composition; both focus on the Southwest region, and both influence a younger generation of artists. For example, Hedger shows Eden his painting “Rain Spirits, or maybe Indian Rain,” “a queer thing full of stiff, supplicating female figures.” Hedger’s explanation to Eden reveals his fascination with the people and culture of the region: “Indian traditions make women have to do with the rain-fall. They were supposed to control it, somehow, and to be able to find springs, and make moisture come out of the earth” (Youth 49). Native American customs and traditions had long been a focus of Blumenschein’s writings and work. For example, in a 1917 article from the American Magazine of Art titled “The Taos Society of Artists,” Blumenschein writes that the Pueblo Indians “have always maintained their customs and their religion even until now, when they are struggling against the mighty white race that threatens to swallow them up and spit them out again” (448). Several paragraphs later, Blumenschein states, “I had to write this little bit about the Pueblo inhabitants if only to counter-act the impression so common in our country that our Indians are not quite respectable” (449). Hedger’s description of his painting is similar to Blumenschein’s 1923 painting Dance at Taos,[4] which depicts several lines of female dancers in a traditional Indian dance and mixes bright colors and shifting forms to create a sense of movement and rhythm. This painting has strong political overtones, for in 1921 the Bureau of Indian Affairs issued Circular 1665, which attempted to ban religious dances. These dances, the circular stated, promoted “[s]uperstitious cruelty, licentiousness, idleness, danger to health and shiftless indifference to family welfare” (qtd. in Miller 123). In Dance at Taos, Blumenschein captures the emotion, movement, and beauty of the ceremony and rejects the notion of its “superstitious cruelty” and “licentiousness.” One can imagine this topic would have been of interest to Cather, who had written about immigrant customs and traditions in her major works.

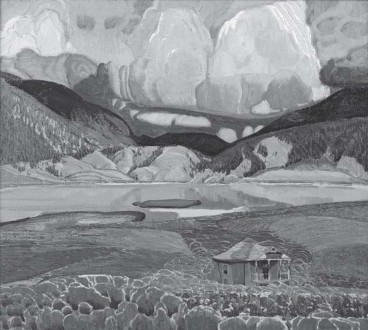

Fig. 6.1. Ernest Blumenschein (1874–1960), The Lake,

ca. 1927. Oil on canvas. 24 1/8 x 27 in. Courtesy of National

Academy Museum. New York.

Fig. 6.1. Ernest Blumenschein (1874–1960), The Lake,

ca. 1927. Oil on canvas. 24 1/8 x 27 in. Courtesy of National

Academy Museum. New York.

Cather may also be referencing Blumenschein through Hedger’s idealism and artistic experimentation. Early in the story, Hedger tells Eden how he is moving away from realistic portrayals in favor of a more impressionistic style: “You see I’m trying to learn to paint what people think and feel; to get away from all that photographic stuff” (Youth 49). Later, when Eden discusses the popular artist Burton Ives, Hedger scoffs at the idea of painting to make money, of painting for the public: “A public only wants what has been done over and over. I’m painting for painters,—who haven’t been born” (61). Twenty years later, when Eden returns to New York and is reminded of Hedger, she asks an art dealer, “Is he [Hedger] a man of any importance?”“Certainly,” the dealer responds.“He is one of the first men among the moderns. That is to say, among the very moderns. He is always coming up with something different” (72). Although this exchange could refer to many painters, Cather seems, at least in part, to be referring to Blumenschein for his embrace of modern art. Like Hedger, Blumenschein was always changing. According to Sascha Scott, Blumenschein’s paintings “underwent a significant stylistic shift” during the late 1910s. He began to experiment with post-impressionist-derived aesthetics, intensified his palette, and “emphasized pattern through the flattening and repetition of forms and often restricted pictorial space by denying illusionistic perspective.” He also focused more on the Native peoples and landscapes of the Southwest and became a leading spokesperson for modern art. In his contribution to Century’s April 1914 “Modern Art Number” on the 1913 Armory Show, “The Painting of Tomorrow,” Blumenschein defends the works displayed at the 1913 Armory Show and explains his conversion to modern art. His words echo those of Hedger. While there have been numerous critics of post-impressionism, Blumenschein argues that by challenging realism and returning to the primitive, post-impressionism has added “a new truth . . . to our knowledge and one which will be welded into all future art” (850; emphasis in original). Given Cather’s interest in art and modern art, it is likely she would have read her “old friend’s” article in Century. By 1914, Cather had two stories published in the magazine,“The Willing Muse” in August 1907 and “The Joy of Nellie Dean” in October 1911, and she was still reading the magazine in 1915; in a 27 June letter she writes Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant that she has just read Sergeant’s article on the poet Frederic Mistral from the July 1915 volume “with the greatest delight!” (Letters 203). Blumenschein continued to defend “modernist” art throughout his career. In a 1919 interview that appeared in El Palacio, Blumenschein is described as a “recognized authority on modern art and on the trend of post-impressionism” (“Blumenschein Is Interviewed” 84). By 1920 Cather had witnessed Blumenschein’s career go from an illustrator for popular magazines to an award-winning experimental painter. In many ways, Blumenschein’s writings and career parallel the idealistic and experimental words of Don Hedger—painting for those artists “who haven’t been born.”

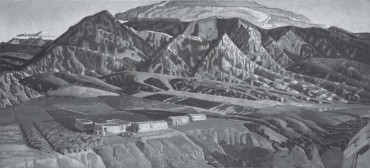

Fig. 6.2. Ernest Blumenschein, Mountains Near

Taos, ca. 1926. Oil on canvas. 22½ x 49½ in. (57.15 x 125.73 cm).

Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Helen Blumenschein. © Estate of Ernest

Blumenschein.

Fig. 6.2. Ernest Blumenschein, Mountains Near

Taos, ca. 1926. Oil on canvas. 22½ x 49½ in. (57.15 x 125.73 cm).

Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Helen Blumenschein. © Estate of Ernest

Blumenschein.

Having established that Cather knew, worked with, and at least partially based a character upon Blumenschein, I would like now to discuss what I think is an even deeper connection between the two artists: the presence of Blumenschein’s work in Death Comes for the Archbishop. By the time of the novel’s publication in 1927, Blumenschein had separated himself from the more traditional Taos Society of Artists, which he had founded, and become a leading American painter and expert on modernist painting. His work became more abstract and experimental in shape and color. While he continued to emphasize Native customs and traditions, he now focused on Southwest landscapes, particularly around Taos and Santa Fe. Finally able to quit working as an illustrator and devote all of his time to painting, he and his family had moved permanently to Taos in 1920. By 1927 he had shown his work around the country and had won several prestigious awards, including a silver medal at the Sesquicentennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1926. Although neither the artist nor his work explicitly appears in the novel, many of Cather’s descriptions bear a visual and thematic similarity to three of Blumenschein’s famous modernist landscapes: The Lake (1927), Mountains Near Taos (1926), and Sangre de Cristo Mountains (1925).

Cather wrote that Death Comes for the Archbishop was partially inspired by Puvis de Chavannes’s St. Genevieve frescoes, which she saw in the Panthéon in Paris in 1902. These two series of murals, the first painted between 1874 and 1878 and the second between 1895 and 1898, depict the life of St. Genevieve in separate panels. In her article on the writing of the novel that appeared in Commonweal on 23 November 1927, Cather states that since she “first saw the Puvis de Chavannes frescoes . . . I have wished that I could try something a little like that in prose.” For Cather, the life of Archbishop Lamy of Santa Fe gave her the opportunity to write “something in the style of a legend, which is absolutely the reverse of the dramatic treatment” (“A Letter” 376). In his 1965 article “Narrative without Accent: Willa Cather and Puvis de Chavannes,” Clinton Keeler explores the connections between the novel and the Puvis murals and asserts that the style of Cather’s novel reflects Puvis’s: both lack movement, both are episodic in plot structure, and both are marked by “flat tones, few contrasts and no vivid colors” with “little distinction between foreground and background” (122). Moreover, Keeler argues, rather than turning inward to explore the artist’s consciousness, as many impressionists would do, Puvis’s work focuses on external and historical subjects: “He avoided the new optical analysis of the impressionists and returned to the monumental painting of the Renaissance” (120). Archbishop, Keeler argues, is similar: “Writing at a time when the innovations of Joyce and others led fiction within the mind, within the process of consciousness, Cather turned to an earlier period” (126). According to Keeler, Cather thus rejects both modernism and impressionism in the novel.

In her 2003 article “Willa Cather and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: Extending the Comparison,” Cristina Giorcelli revisits the connections between the murals and the novel. While she argues that Keeler’s main points are “indisputable,” Giorcelli does not view either artist as rejecting modernism and impressionism; rather, she considers Cather’s attempt at re-creating Puvis’s style an embrace of a modernist aesthetic. While his work has often been considered traditional, writes Giorcelli, “several art historians have claimed that Puvis is, in effect, the hidden, inescapable master of such avantgarde artists as Cezanne, Picasso, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Seurat, Matisse, Degas, Brancusi, Malevich, Munch—that is, of cubism, fauvism, and expressionism” (73). While the murals and the novel are traditional in subject, they are experimental in form and technique. According to Giorcelli, “Cather must have detected in the work of Puvis certain aspects of modernist originality Cather’s modernist quest probably found in Puvis’s art an inspiration and model for her own masterpiece, its chromatic hues, moods, detail, and, above all, structure” (86). It is my belief that Cather’s “modernist quest” may also have been complemented by the works of her “old friend” Ernest Blumenschein.

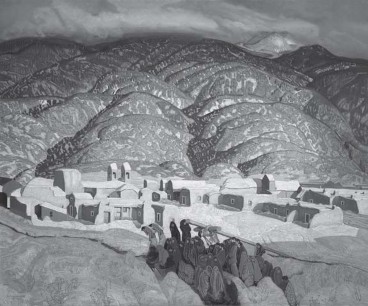

Fig. 6.3. Ernest Blumenschein, Sangre de Cristo

Mountains, 1925. Oil on canvas. 50½ x 60 in. Courtesy of American

Museum of Western Art, Denver—The Anschutz Collection. Photo by William

J. O’Connor.

Fig. 6.3. Ernest Blumenschein, Sangre de Cristo

Mountains, 1925. Oil on canvas. 50½ x 60 in. Courtesy of American

Museum of Western Art, Denver—The Anschutz Collection. Photo by William

J. O’Connor.

It is easy to see similarities between Blumenschein’s paintings and Cather’s descriptions of the New Mexico landscape. Both the novel and the paintings depict the natural beauty of the region, specifically the vastness of the land and sky in contrast to the minuteness of humankind, and each creates landscapes characterized by motion and shifting light. The Lake, one of Blumenschein’s modernist landscapes, shares many similarities with Cather’s descriptions (fig. 6.1). This painting centers on a scene with heavy thunderclouds looming above, and the viewer’s gaze is directed not toward the lake or the cabin in the foreground but rather to the oval clouds swirling in the vast sky. Shadows spread across the lake, the mountains, and the fields. Light breaks through above the clouds, but below, darkness and shadows dominate, and the lake reflects this changing sky. Almost hidden in the valley, the solitary cabin is dwarfed by the mountains and clouds. While Blumenschein paints one specific moment, the dominant impression is one of motion; the shifting storm clouds alter the reflections and the shadows, and the viewer feels that if he turned away for just one second, the entire scene would change. According to Peter Hassrick, the painting provides “an impressive contrast in nature’s moods”; the calm scene of the lake and the small home are in sharp contrast to the dark storm clouds on the horizon, and the “painting pulsates—its air is as electric as it is fresh” (162). Blumenschein worked on The Lake between 1923 and 1927 and presented it to the National Academy of Design when he was inducted into the academy in 1927 (Hassrick 162).

It is possible that Cather saw The Lake during her visits to the Southwest in 1925 and 1926 while she was composing her novel. Cather’s descriptions of the sky also pulsate with electricity, and they resemble Blumenschein’s painting in several ways—the vastness of the land and sky, the altering of the landscape by the shifting light, and the smallness of humanity in comparison to the natural world. Bishop Latour, for example, comments several times on the awe-inspiring and changing nature of the sky. In book 2, when he recalls his first travels to “mesa country,” he notes the difference between the Southwest and other areas of the nation. On his journey through the Midwest he had “found the sky more a desert than the land; a hard, empty blue,” but in the Southwest the sky is constantly changing, and the huge clouds reflect the land below. Latour observes, “there was always activity overhead, clouds forming and moving all day long”; these changing cloud formations, “[w] hether they were dark and full of violence, or soft and white with luxurious idleness,” dramatically change the landscape, and this constant shifting of light and shadow alters both the land and human perspective. “The desert, the mountains and mesas, were continually reformed and re-coloured by the cloud shadows”; to him “[t]he whole country seemed fluid to the eye under this constant change of accent, this ever-varying distribution of light” (100–101). Later in the novel, Latour again comments on the changing nature and vastness of the Southwest sky in contrast to the smallness of humankind, observing that in the Southwest,“the sky was as full of motion and change as the desert beneath it was monotonous and still,—and there was so much sky, more than at sea, more than anywhere else in the world.” Everything is small in comparison. “Even the mountains were mere ant-hills under it” (245).

In addition to The Lake, a series of paintings Blumenschein completed of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains also offer a striking similarity to Cather’s prose descriptions. The Sangre de Cristos, which surround the Taos valley, represented to Blumenschein the essence of Taos; in 1917 he wrote: “One can’t tell about Taos without dwelling on the mountains that box in the valley on three sides” (“Taos Society” 445). He celebrated these mountains in many paintings, but one of his most famous is Mountains Near Taos (1926) (fig. 6.2). This painting captures the light of the afternoon sun on the mountains and a small settlement. As he did in The Lake, Blumenschein depicts the changing nature of the sky, the vastness of the land, and the comparative smallness of humanity. The painting is centered on the pyramid-like mountains that tower above the valley and the pueblo. Although these angular, purple-shaded mountains appear barren, upon closer inspection they are partially snow-covered and forested with aspens and evergreens, a stark contrast to the undulating and fertile Taos valley. The sun is to the right, out of the frame, and the reflection on the mountains and shadows on the valley and pueblo indicate a late-afternoon setting. Behind the mountains, but only partially in frame, a thundercloud looms, and in front of the pueblo a small, barely visible crowd is gathered. The perspective of the painting, elevated and distant, provides a panoramic view of the entire valley. Although, unlike The Lake, Mountains Near Taos is not centered on motion, the shifting of light and shadows does create a sense of movement. The movement, however, is based on the daily passage of time as opposed to a fast-moving thundercloud. Blumenschein’s vibrant use of color, embrace of design, use of angular shapes almost to the point of abstraction, and contrast of light and dark to create form qualify this work as modern (Hassrick 178).

Cather’s description of the Taos valley in Archbishop echoes Mountain Near Taos in the use of color, the emphasis on the ever-changing light and sky, the depiction of the smallness of humanity in comparison to the natural landscape, and the focus on the sharp tips of the mountains as a contrast to the fertile valley. Bishop Latour and Father Martinez pause before Taos pueblo “gold-coloured in the afternoon light, with the purple mountain lying just behind them.” The entire scene is bathed in purples, golds, greens, and pinks; Cather refers to “Gold-coloured men,”“clouds of golden dust,” the “purple mountain,” the “light green” mountain forest, and the “pink adobe town” (158–59). These are not Keeler’s “flat tones,” but vibrant and distinct colors. Cather’s narrative also emphasizes the changing nature of the light. A group of men are gathered, Latour observes, “apparently watching the changing light on the mountain.” These are similar to the barely visible figures Blumenschein includes in his painting. Also like Blumenschein, Cather emphasizes the mountain: “Though the mountain was timbered, its lines were so sharp that it had the sculptured look of naked mountains like the Sandias. The general growth on its sides was evergreen, but the canyons and ravines were wooded with aspens” (159). Even the perspectives are the same. Blumenschein’s point of view, like Latour’s, is elevated and distant, almost at eye level with the mountains and looking down into the Taos valley. When Latour travels to Arroyo Hondo and approaches the village, he is stopped at a step canyon: “Drawing rein at the edge, one looked down into the sunken world of green fields and gardens, with a pink adobe town, at the bottom of this great ditch” (174). This is not an antimodernist description, as Keeler might argue. In fact, the similarities to Blumenschein’s painting—the vibrant use of color, the use of angular shapes, and the contrast of light and dark to create form—qualify this work as modern.

Unlike the previously discussed paintings, Blumenschein’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains (1925) shares a thematic rather than a stylistic similarity to Cather’s novel, although the painting does share similarities with the works just discussed (fig. 6.3). This large painting is, according to Hassrick, “historic in narrative and modern in treatment” (168). A pueblo village shining in the winter afternoon sun centers the painting, but the bulk of the canvas is taken up with the snow-covered Sangre de Cristos, which remain mostly in shadow. In this version, the mountains are not sharp but rounded, almost billowy, and the dark and fast-moving storm clouds add a somber and threatening element to the painting. This mood is enhanced by the procession of penitents and their onlookers in the foreground of the canvas, their bent backs mirroring the curves of the mountains. Carrying a cross through the snow-covered fields, this group is a part of the Penitente Brotherhood, a sect devoted to the suffering of Christ and characterized by their willingness to inflict pain upon themselves. This is Taos in the mid-1800s, then known as Don Fernando de Taos, around the time of the setting of Death Comes for the Archbishop. Sangre de Cristo Mountains resembles the previously discussed Blumenschein paintings stylistically, as well as Cather’s descriptions of the mountains and the Taos valley: the changing and shifting light, the vastness of the landscape and sky, and the smallness of humanity in relation to nature. Blumenschein’s use of light and shadow, his vibrant colors, and his abstract rendering of the mountains are again evidence of his developing embrace of modernism.

While Cather does not refer to this exact scene in Archbishop, the thematic similarities between the painting and Cather’s novel are worth exploring, especially Cather’s references to the Penitentes in book 5. Father Martinez warns Latour against attempts at reform of the brotherhood: “If you try to introduce European civilization here and change our old ways, to interfere with the secret dances of the Indians, let us say, or abolish the bloody rites of the Penitentes, I foretell an early death for you” (55). These “old ways,” while outdated, still hold importance among the Native peoples. Trinidad, perhaps Father Martinez’s son, embraces this “fierce and fanatical” sect (160). Martinez explains that during Passion Week, Trinidad “goes up to Abiquiú and becomes another man; carries the heaviest crosses to the highest mountains, and takes more scourging than anyone. He comes back here with his back so full of cactus spines that the girls have to pick him like a chicken” (156). Senõra Carson, wife of Kit Carson, later informs Latour how during Passion Week in Abiquiú, Trinidad had tried to be crucified but was too heavy and the cross fell over. He then tied himself to a post “and said he would bear as many stripes as our Savior—six thousand, as was revealed to St. Bridget.” He could barely take one hundred before fainting. The people of Abiquiú “[t]his year sent word that they did not want him.” When Latour asks if he should forbid these practices, Senõra Carson replies: “It will only set the people against you. The old people have need of their old customs” (163). John Murphy writes that Cather read several firsthand accounts of the brotherhood (449–50). Perhaps she had seen this depiction of the brotherhood in Blumenschein’s masterpiece.

Willa Cather and Ernest Blumenschein were friends for much of their lives, and in many ways their careers parallel each other; born within a year of one another, both served long apprenticeships, Cather as a journalist and Blumenschein as an illustrator, and both became celebrated and famous artists. Although Cather refers to Blumenschein as one of her “old friends,” her connection to the painter has never been explored. While we cannot be sure how many times Cather and Blumenschein visited each other, or even when their acquaintance began, we know he is a presence in her fiction. Cather refers directly to Blumenschein in “Coming, Aphrodite!” when she emphasizes the experimental nature and idealism of Don Hedger’s Southwest work. Hedger, like Blumenschein, is an artist willing to change, but one who remains true to his ideals. Hedger, like Blumenschein, embraces modern art and techniques and eventually becomes an important influence on a younger generation of painters. In Death Comes for the Archbishop, Cather’s stylistic and thematic similarities to three of Blumenschein’s paintings indicate that Cather was likely aware of her friend’s modernist landscapes. Both his paintings and Cather’s descriptions emphasize the changing nature of light and the ways that light alters one’s perspective. While Keeler may have argued that Archbishop is distinctly antimodern, like Blumenschein’s paintings, it is squarely within the realm of modernist experimentation.