From Cather Studies Volume 12

Memory and Image: Graphemics for a New Frontier Icon in My Ántonia

Almost half of the way into Willa Cather’s fictional memoir of life in frontier Nebraska, four young pioneer women and a young man are visited by an image that appears to be written against the sky. The viewers are at first speechless, so drawn to it that they jump up to stand at attention before a signifier as commanding as a national flag. Much in the way that a national flag can communicate symbolically to a nation of people their shared experiences and values, the fleeting phenomenon of the plough silhouetted on the setting sun is instinctively understood by these young people as an icon of their own lives on the prairie.

My Ántonia is a novel of memory elegizing the late nineteenth-century plains culture of North America, narrated by its orphan character from Virginia, Jim Burden. It is a double narrative of the passage into early adulthood, tracing Jim’s maturing consciousness as it meditates on and is shaped by the life of his closest childhood friend, Ántonia Shimerda. She is the luminous image at the center of both his narrative and his mind. As an inventory of Jim’s memories of Ántonia, the novel’s narrative structure and characters seem fairly straightforward, and yet this work is also inscribed with a dense and highly elaborated code of visual and verbal images, a code predominantly derived from the popular visual culture of late nineteenth-century American frontier life. Cather drew these images largely from those pictorial sources most commonly available to people who lived and worked on the Great Plains then, and with W. T. Benda, her illustrator for the novel, she shaped them into a visual lexicon that forcefully represents Jim Burden’s formative memories.

Many of Jim’s memories are simple still and moving images of Ántonia, representing the experiences that he shared with her. Although the first edition’s introductory emphasis on “seeing” Ántonia by evoking her in the mind’s eye was eliminated in her 1926 revision (Woodress 389), Cather’s figurative language throughout the narrative shares the naïve quality of these picture-memories. This seemingly transparent verbal imagery finds its visual parallel in the stark drawings that the illustrator Wɫadysɫaw Teodor Benda produced for My Ántonia. I agree with the scholars who have called for a detailed consideration of this novel’s images, but would add that a critical method grounded in theories of the image, the relationships between image and text, and visual culture, especially the popular visual culture of the late nineteenth century, is essential to understanding the success of this work. Under Cather’s specific directives, Benda’s drawings for My Ántonia were resolved into a subtle pictorial formula that was based, to a significant extent, on an earlier period of nineteenth-century illustrational practice. Benda worked within this formula to produce a suite of illustrations that constitute half of a bitextual graphemic system operating within the novel. The other half includes indelible images that Cather produced in words, such as her image of the plough against the setting sun. By carefully placing Benda’s inventory of graphic images into a dialogue with her own picture writing, Cather convincingly elevates the character and social value of the immigrant pioneer woman.

It has often been noted that Cather was actively involved in the art and design considerations for her publications; nevertheless, the insistence with which she fought for W. T. Benda’s eight drawings to be included in My Ántonia stands as a distinctive part of the novel’s history. Cather’s correspondence makes clear her intention to place an embedded visual narrative alongside the verbal narrative of Jim’s friendship with Ántonia (Mignon and Ronning, preface to the scholarly edition of My Ántonia). These linked narratives together represent the passage of each of the characters into adulthood; each responding to the other, they elaborate and ultimately establish the iconic identity that Ántonia comes to possess in Jim’s mind. Using sophisticated illustrational techniques, Benda carefully orchestrated sources from visual culture both high and low for his illustrations, producing a series of images that, in large part because of these blended cultural sources, are credible as Jim’s memories and imaginings. These images powerfully communicate Ántonia’s significance, first to him, and then through the compelling female icon in his mind’s eye, to the novel’s readers.

Cather scholars have carefully considered the sources and effects of the Benda illustrations. Jean Schwind’s probing of the illustrations as paratexts that express Jim’s memories establishes some of the nineteenth-century American landscape painters treated in Cather’s early art reviews as likely influences for these eight drawings. John J. Murphy’s commentary on “Cather’s Use of Painting” in My Ántonia, The Road Home is a rich catalog of the examples of French and American impressionism, realism, genre painting, and luminism that fed Cather’s specific visualizations for the novel (45–56). In Picturing a Different West: Vision, Illustration, and the Tradition of Cather and Austin, Janis Stout’s elegant comparison of Cather’s minimalist technique to the style of the Benda illustrations introduces the early twentieth-century compositional practice central to Benda’s simple drawings. Her commentary points to the defining distinction between the style of drawings created as illustrations for written texts and the rigorously elaborated style of academic drawings that capture the observed subject. Following Stout, Evelyn Funda’s “Picturing Their Ántonia(s): Mikoláš Aleš and the Partnership of W. T. Benda and Willa Cather” examines the possible influence of some sources of American popular illustration on Cather and Benda as they collaborated. In particular, her essay explores the graphic and folk art forms from Czech popular culture given significant public reception in America during the first decades of the twentieth century. Whether or not Cather and Benda actually viewed the work of highly regarded Bohemian illustrators such as Mikoláš Aleš, in whose drawings Funda finds much basis for comparison to those of Benda, she convincingly details the presence of Czech visual culture in American cities and towns.

Schwind, Murphy, Stout, and Funda assume a critical distance between Cather and Jim Burden; in so doing, they place the sophisticated art knowledge of the novelist over the uncomplicated memories of her country-bred lawyer character. In connecting the illustrations with illustrational styles likely known by a seasoned arts professional, they tend to locate their sources in Cather’s mind and experience. Schwind, for instance, puts much credence in Cather’s knowledge of nineteenth-century painting as a source for Benda’s illustrations, but perhaps not enough in the popular illustrational practice of adapting these painting sources for commercial purposes. As an experienced editor, Cather would have known about this common adaptive practice.[1]

My own reading of Benda’s drawings identifies them more narrowly as products of Jim’s consciousness: with Schwind, I believe that Cather intended them to be a “silent supplement” to the loosely organized writings contained in his legal portfolio. And while I agree entirely with Stout’s reading of the image of the plough as “a defining emblem” of Cather’s heroic vision of a more agriculturally focused and socially inclusive frontier (125), I read both the verbal and visual “pictures” that were crafted for this novel as comprising, in their common starkness, graphemics for Jim’s more personal, individual language of his pioneer West. It is precisely through Jim’s remembered mental images, born within his character and the experience he narrates, that Cather wishes us to read her vision of the precious past.

If Benda’s drawings were intended primarily as figures of Jim’s private memories, we should ask how the influence of European and American art and illustrational practices on these images contribute to the novel’s success. The associations made by Schwind, Murphy, Stout, and Funda between the novel’s images and the world of art traditions that Cather knew so well certainly confirm an aspect of Cather’s critical visual acuity. They also provide valuable context about diverse practices of image-making before and during the time that the novel was produced. They don’t, however, align with the visual sensibilities of her main character or with his memories of Ántonia. My own critical tendency with regard to this question is to move from considering the art contexts of Cather’s narrative to a visual analysis of the novel itself. I examine the novel from the angle of contemporary theoretical approaches that address the phenomenon of the image in art and in culture. As these may better reveal the specific effects of Benda’s images on Cather’s narrative, I offer the following brief review of image, image/text, and visual culture theories as a basis for exploring the relationships between Cather’s word images and Benda’s drawings.

VISUAL CULTURE THEORY: MEMORY, IMAGE, AND TEXT

The inquiry into the place of the image in cultural exchange has assumed its unique power in the generation of social meaning. Historical studies of fine art measure its social influence as stemming from its locale in galleries or collections—an understanding which necessarily restricts that influence to those members of society who, before the eighteenth century, had the privilege of viewing access. Since the years of mechanical reproduction and increased exhibition of images on all social levels, however, the idea of the image’s social power has been reconceived. We now see the image as a phenomenon with a broader base of cultural participation and a wider social application. In What Is an Image? W. J. T. Mitchell summarizes ideas about the nature of the image and its roles. By deconstructing commonly held notions, such as the separation between language and the image, he argues that the image is neither free of language nor of the cultural framework in which it is produced and exists: “the relationship between words and images reflects, within the realm of representation, signification, and communication, the relations we posit between symbols and the world, signs and their meanings” (529).

Additionally, Mitchell separates images from their conception, held in ancient and medieval centuries, as a discreet and “material” form of representation (521). I hope to show that, contrary to common belief, images “proper” are not stable, static, or permanent in any metaphysical sense; they are not perceived in the same way by viewers any more than are dream images; and they are not exclusively visual in any important way but involve multisensory apprehension and interpretation. (507)

Instead, he and other critics (such as Victor Burgin and Nicholas Mirzoef) stress the idea of the image as a social-cultural construct, in its production and its interpretation, a phenomenon of both outer and inner worlds of signification, entangled with processes of language and with other human processes of mental and emotional passage. This expanded approach to images raises new questions about both their creation and interpretation, as Burgin argues that “representations cannot be simply tested against reality, as reality is itself constituted through the agency of representations” (238).

Imaging technologies and ideas about the visual had already begun to characterize life in America and Europe after the mid-nineteenth century. Although the term visual culture is most commonly applied in theories of postmodern life, its application extends backward as well to the period from the mid-nineteenth century to its turn. Mirzoef defines the workings of this visual culture: Visual culture is concerned with visual events in which information, meaning, or pleasure is sought by the consumer in an interface with visual technology. By visual technology, I mean any form of apparatus designed either to be looked at or to enhance natural vision, from oil paintings to television and the Internet. Such criticism takes into account the importance of image making, the formal components of a given image, and the crucial completion of that work by its cultural reception. (3)

This approach posits the image as at once a manifest representation and a corresponding complex of inward meanings that a viewer, at a deeper level of consciousness, reconstructs individually as a private associative representation. The artist’s image results from a similar process of significatory construction, which viewers consciously interpret. Initiated by the conscious experience of the image as a sensory stimulus, it then becomes involved in the preconscious mental and emotional processes of individuals, such as memory, or in their subconscious processes, such as dreaming. In these “secret” contexts, the image is seen to feature critically in the service of psycho-emotional needs. In In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture, Burgin proposes the idea of the memory as image. Building on Freud’s work on memory, he establishes the location of all memory in the unconscious mind, with the qualifier that “what in everyday speech is called ‘memory’ is located in the preconscious” (217). He also makes use of Freud’s concept of the “screen memory,” a preconscious memory which is substituted for a related memory that a person may wish to suppress (221), observing that screen memories highlight “the role of language—‘verbal bridges’ (Freud, qtd. in Burgin) in the construction of mental images, and the role of fantasy in the (re)construction of our memories” (223). The memory as shared in everyday life then becomes a synthesis of remembered sense impressions deployed strategically to construct through “memories of facts . . . memories of images, or of words, and even with memories of memories” a composition arising from unconscious and conscious processes, resulting in a representation of human experience (Taranger, qtd. in Burgin 228). Summoned in the mind’s eye, and constructed in a manner analogous to that of the image, memory then participates in visual culture as both a producer and a product. In this view of it, memories can be “read” or interpreted in ways similar to the ways that we read and interpret images.

We can pursue the mental image’s constructed aspect in Jim’s two recurrent adolescent dreams of Ántonia and Lena in “The Hired Girls.” He summons the first explicitly from his memories of being with Ántonia when they were even younger children: “I used to have pleasant dreams: sometimes Tony and I were out in the country, sliding down straw stacks as we used to do; climbing up the yellow mountains over and over, and slipping down the smooth sides into soft piles of chafe.” (218) Jim’s dream image is an assemblage, culled from recalling the sight of the straw stacks in the country, from remembering the game of climbing up and sliding down them, from the wordless pleasure of being united with Ántonia in child’s play. Part of this memory depicting innocence in simple repetitive motion may also be derived from late-century forms of moving pictures that he may have seen, such as chronophotography or a timed Eadweard Muybridge proto-movie. He also shares his recurrent dream of Lena: I was in a harvest-field full of shocks, and I was lying against one of them. Lena Lingard came across the stubble barefoot, in a short skirt, with a curved reaping-hook in her hand, and she was flushed like the dawn with a kind of luminous rosiness all about her. She sat down beside me, turned to me with a soft sigh and said, “Now they are all gone, and I can kiss you as much as I like.” (218) The dream of Lena again consists of elements taken from Jim’s sight memories of shocks and stubble at harvest time, of Lena’s bare legs and feet, and her ruddy complexion—sights that he recalls from an earlier, no less sexually aware description of her in book 2, and that his subconscious mind now deploys in the dream image, embellished with the symbolic reaping hook. Besides being obviously constructed of bits and pieces of Jim’s everyday experience, the two dreams comment on one another in revealing ways about Jim’s passage from childhood into early adulthood. In his “pleasant” dream of her, Ántonia features as a fellow child, and their play, though repetitive, holds no urgent longing for future relationship intimacy. The dream world with Lena, though, is a place of desire, as expressed (on behalf of an adolescent Jim) by Lena’s wish to kiss him to her heart’s content. Jim’s subconscious mental image of Lena charges the details of her normal appearance with a sexual meaning—amplified in Benda’s portrait of her—that is easily correlated with this dawning awareness.

Jim’s dreams can thus be understood as representations of his mind far below the conscious level, constructed both from his conscious experiences, his preconscious memories, and the signifying processes of his subconscious mental states. They are narrated to us in the form of memories-as-images that echo specifically the complex intensity of his feelings about his Ántonia and his child-self, and about his passage into an adult self, beckoned by Lena. These two dream images are placed toward the end of book 2 at the juncture of Jim’s departure from Ántonia and his movement toward his adult relationship with Lena. The remembered image of the plough follows these dream images in the penultimate chapter of book 2. It can also be read as an image construct, one that exists briefly as a construction of happenstance on the sunset fields, an illusory phenomenon of visual stimulus for the young pioneers who witness it. Together, they process it from an external stimulus to an internal construction in the mind’s eye, as part of their interpretive process. But as an image in the external world, it is dependent on the passage of the sky’s light, and so fades from Jim’s sight: “that forgotten plough had sunk back to its own littleness somewhere on the prairie” (238).

Christina Ionescue and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra have established provocative approaches to illustrated books that are useful when thinking about the effects of Benda’s illustrations. The central contest in theories of book illustration is summarized by Christina Ionescu as the question of dependency in the relationship between word and image. Notions of the image as a visual paratext, or as part of an iconotext, commonly posit the image as dependent on the text for its ultimate significance (33). In The Artist as Critic Lorraine Kooistra applies Bakhtin’s idea of the “dialogic imagination” to theorize the dialogic relationships between image and text in the nineteenth-century illustrated book. Kooistra points out that the popularity of illustrated serialized fiction in the later nineteenth century allowed for a sustained critical dialogue between text and image and for deeper critical engagement of readers than did the illustrated books of earlier decades (2). Thus late nineteenth-century readers of popular illustrated narratives may have anticipated Mieke Bal’s resolution of the text/image debate: “The image does not replace the text; it is one” (22). W. J. T. Mitchell characterizes this relationship as a fluid partnership: The recognition that pictorial images are inevitably conventional and contaminated by language . . . [implies] for the study of art . . . simply that something like the Renaissance notion of ut pictura poesis and the sisterhood of the arts is always with us. The dialectic of word and image seems to be a constant in the fabric of signs that a culture weaves around itself. (529)

We can read Cather’s letters to Ferris Greenslet within this context. Two of her letters to Greenslet insist that his drawings be able to “echo” the illustrations that she tried to draw herself before beginning to work with Benda (245). In connection with her words, his images should “give the tone of the text” and must “have some character and interpret and embellish the text” (247) (italics mine). Her characterization of these images’ function suggests the dialogic, as Kooistra uses the term, but also stipulates their possession of the complementary quality that Kooistra assigns to the specific dialogic relationships of “impression” and “answering.”[2] Cather also sees each type of text as both independent and as involved in the cross-commentary essential to critical reading. They also reveal her preference, at least in My Ántonia, for a unity or “sisterhood” between words and images.

VISUAL CULTURE CONTEXTS OF CATHER'S PICTURE WRITING

From the mid-nineteenth century through the early twentieth, Americans experienced a steady rise in their access to art images in a multitude of print forms such as books, magazines, newspapers, commercial catalogs, playing and trading cards, public posters, and even colored paper figures and scenes used, as were those unearthed from the lining of Otto’s trunk, as Christmas decorations. According to James J. Best, in American Popular Illustration, the appetite for Civil War news was the principal social stimulus for the development of an American industry of illustration in which artists were assigned to travel and work with reporters, producing images to accompany news stories (3–4). The woodcut engraving was a common type of mass-produced image in wide distribution in the nineteenth century. Reproductive technologies evolved rapidly during the Civil War. The resulting later-century proliferation and mass production of illustrated reading material widely disseminated visualizations of American life both romantic and sentimental.

Jim’s world features an expanding presence of mass-produced images. Jim’s first Nebraska Christmas tree, decked with paper treasures sent from Austria by Otto’s mother, surely owed much of its effect to the magic of the mass-produced image: brilliantly colored paper figures, . . . a bleeding heart, the three kings, gorgeously appareled, and the ox and the ass and the shepherds; . . . the Baby in the manger, and a group of angels. . . . Our tree became the talking tree of the fairy tale; legends and stories nestled like birds in its branches. (80)

Fig. 1. Thomas Bewick, Hunter Precariously Retrieving Duck

from River, 1804. From History of British Birds

1797–1804.

Fig. 1. Thomas Bewick, Hunter Precariously Retrieving Duck

from River, 1804. From History of British Birds

1797–1804.

For My Àntonia’s visual images, Cather repeatedly told her publishers that she saw the look of the woodcut as particularly appropriate for her illustrated narrative. Printing with the woodblock at the turn of the twentieth century evoked a simpler time partly through its simpler technology; it could recall for its viewers a time that was lost, and so it was a way of figuring human longing. Although these materials were replaced after the war by high-speed presses and more efficient plate technologies that significantly decreased the costs of printing artwork, the woodcut reemerged in commercial art after World War I, thus raising the costs of print production (Best 135). Given Cather’s editorial savvy, the postwar commercial comeback of the woodcut may have coincided nicely with her desire to develop, with Benda, a nostalgic “look and feel” for the My Ántonia illustrations.

Fig. 2. Albert Potter, Eastside New York, 1931.

Courtesy of the Estate of Albert Potter and the Susan Teller Gallery, New

York.

Fig. 2. Albert Potter, Eastside New York, 1931.

Courtesy of the Estate of Albert Potter and the Susan Teller Gallery, New

York.

Woodcut technology in the simple form of woodblock prints dates back to eighth-century Japan, but in seeking the look of “old woodcuts,” Cather would most likely have been referring to the production of prints through woodcut techniques that were used in Europe during the early fifteenth century. In its basic production of the image, the woodcut is a relief print, which eliminates all areas of a surface of wood except the raised lines or shapes that then provide the outlines of the printed image. It was easy to use woodcuts for book illustration early in the history of print culture, and the streams of printed images produced in the second phase of the Industrial Revolution carried woodcut technology and images into the mid-nineteenth century (Thompson). Although technical innovations then made possible the use of color in the mezzotint and aquatint (and enabled the refinement of the image), the simpler, heavier line of the earlier woodcut processes are clearly what Cather sought and Benda imitated in the illustrations for My Ántonia.

The woodcuts in figures 1 and 2 (1804 and 1931) are later examples of the denser and heavier line of the woodcut processes of centuries earlier, showing the simple articulation of the human form and landscape typical of the medium. The latter is an example of the return to the look of old woodcuts in commercial print production which began in the late nineteenth century.

As Stout has astutely characterized them, Jim’s mental pictures of Ántonia are communicated in a language spare and minimal, a style comparable to that of early woodcuts, as Benda’s drawings incorporate it. But where Stout sees the illustrations as capturing the western landscape in the “open space and big skies,” I read those open spaces as the white surface upon which Benda, under Cather’s guidance, created drawings based on the simple, crude lines of early woodcuts, evoking the naïve utterance of young Jim’s pure emotions. They express his profound desire to hold the outline of Ántonia in his mind as the essence of his deepest yearning, perhaps as a screen memory of the mother whom he lost so early or, as he confides to her,“anything that a woman can be to a man” (312). Jim’s primary source for this closely held image construct is most likely influenced by the food of female figures in woodcut engravings, silhouettes, and portraits that would have, at this moment in the history of American visual culture, made their way even into his isolated life on the plains.

Taken together, My Ántonia’s visual and verbal images are a system of picture writing, one of the principal strategies that Cather employs in sharing with us her own ideal of the pioneer. In my commentary on The Profile, I appropriated Cather’s phrase “picture writing” from book 2 of My Ántonia to identify her diverse yet consistent use of visual semiosis as a salient aspect of her narrative rhetoric (Cather Studies 9,“The Cruelty of Physical Things”). She held the juncture of words and images to a high standard, and Benda’s drawings clearly met her standard for illustrated literature, at least in the case of this novel. The central importance of these images lies in the fact that they inscribe a critical passage of Jim’s subjectivity into the novel. All eight of the images suggest in their naiveté Mitchell’s notion of the “verbal icon”: a preconceived sign recognized in the mind before either word or image has formed to capture its significance.[3] Additionally, all eight can be recognized as Burgin’s memory-as-image, narrated/pictured from the distance of Jim’s adult consciousness. Together they constitute a visual narrative of his identification with Ántonia. Thus the novel’s structure is based on a double narrative that convinces readers of the personal and social value of Ántonia’s womanhood: as Jim’s subjective identity is increasingly shaped by his memories/images of her, her character, as the object of his identification, is transformed by Benda from immigrant girl to a new type of American female icon.

From the eighteenth century, there had existed established middle and working-class markets for illustrated texts, and the growth of inexpensive technologies for producing engravings supported their rising popularity well into the next century. Nonetheless, the literary establishment often drew a critical line to exclude the image. As Brake and Demoor have shown, many writers stood behind that line with Wordsworth: “Avaunt this vile abuse of pictured page! Must eyes be all in all, the tongue and ear nothing? Heaven keep us from a lower stage!” (Illustrated Books and Newspapers, 1846 171). One might argue that Cather worked within a literary tradition in which book illustration was placed firmly at the bottom of a cultural hierarchy and seen as an impediment to raising the popular literary taste to a reasonably informed standard (5). In a similar vein, Kooistra points out that in the 1890s, “many fin-de-siècle illustrators set out to be interpretive readers of the texts they embellished” (3). By the second decade of the new century, such notions were widely received among consumers of books and magazines; the image, as stated in 1914 by M. C. Salaman in Modern Book Illustrators and Their Work, “should actively interpret for us the literary idea . . . with decorative effect” (qtd. in Kooistra 16). Thus as Cather and Benda collaborated to produce a bitextual novel, the reading public had begun to embrace such narratives, making Cather’s previous reluctance to publish them the most significant critical resistance under which the two may have labored.

In the novel’s two narratives, popular images, notably the old woodcuts that Jim would have seen as a child, intersect with private mental images to provide a basis for his memories of Ántonia and thus for Benda’s images of her. Jim’s memories of the orphaned portion of his childhood are constructs of his past relations with his mother, Ántonia, and the other women in his life. And Benda’s drawings capture the emotional tone of Jim’s longing through references to the nostalgic popular arts of the past. They offer to our minds a story told in picture memories of a young immigrant girl whose gathering strength and generosity not only restore Jim’s sense of family, but make possible the survival of her own family and its future.

POPULAR VISUAL CULTURE AND BENDA'S IMAGES

In his regular commercial practice, Benda’s illustrational style was distinctive, despite the familiarity of his subject—woman— and his romantic realism—the preferred style of art for many of America’s leading illustrators. His women were often foreign, “orientalized” images that contrasted with the more familiar and sentimental “American Beauty” images produced by Charles Dana Gibson and Howard Chandler Christy. Despite this distinction, however, his customary style was consonant with the standard realism of the illustrators of this time. The amount of detail in Benda’s usual line and shading stands in high contrast to his handling of those elements in the drawings for My Ántonia. There, Benda’s images are less evidently realistic, styled in the manner of early woodcuts. His illustrations bear an expressive yet abstract quality: they depict figures as seen in the mind’s eye. Thus they are more easily read as essentially private memories than as the type of historically accurate narrative scenes championed by Howard Pyle, who trained many of America’s foremost golden age illustrators (Best 8).

As Banta explains in Imaging American Women, the various socially accepted American female types represented in the images of women that were widely disseminated in journals, magazines, and posters at the turn of the twentieth century were read by the public as the standard of all that was American: She had to be visibly feminine, thus eminently marriageable, lest the truth, goodness, and beauty she emblematized go to waste and the “Americanness” of her bloodline be subsumed by the unassimilable alien hoards proliferating like rabbits in slum neighborhoods and prairie towns. (109) Banta sees the prevalence of woman as the American cultural icon as a strategy to suppress the rise of the socially atypical or foreign, as represented by the recognized immigrant types. The ideal American woman represented exclusive categories of social standing, rising into which was understood to be unlikely or impossible for young immigrant women.

Each of the illustrations that Benda produced for Cather assures us of the suggestive power of the image to capture the primacy of Cather’s female figure. Cather’s narrative and Benda’s images enter into a dialogue producing a strong visual/lexical rhetoric that convinces readers of Ántonia ’s iconic status as a new heroic type of American woman. Especially in her valorization of Ántonia as a Bohemian beauty, and in her guidance of Benda’s images for the novel, Cather can be seen to propose an alternate type for the immigrant, lower-class woman like Ántonia who, in Jim’s heroic vision of her, could rise to suit a particular standard of social worth.

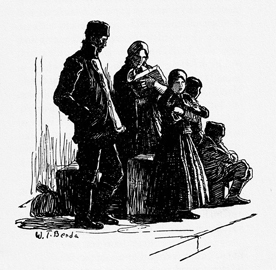

Fig. 3. W. T. Benda, The Shimerdas, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 3. W. T. Benda, The Shimerdas, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Placed carefully by Cather, the eight drawings collectively contribute the story of Jim’s inner growth to her broader narrative arc of two friends growing up in the last decades of frontier Nebraska. The events comprising Cather’s story are made up of chapters gathered into five books. Although it is built of dramatic constituent events throughout (Jim’s arrival in Black Hawk, Mr. Shimerda’s suicide, the town dances, Ántonia’s trouble with Wick Cutter, Jim’s departure for the University and long-delayed return to the Cuzak farm), the visual storytelling moves at a more stately, if uneven, pace. Book 1 contains six of the eight illustrations, while book 2 has only one, and the last of the eight is tucked into book 4. The distribution of the pictures limns the emotional passages of Cather’s central character. Visual images carry forward through the narrative, revealing Jim’s inner journey from boyhood to manhood. They mark his passage through a period of mourning for his parents, through the stages of his close identification with Ántonia, and through the inevitable changes to their relationship brought by their maturing processes. Finally their lives diverge, but each has stayed connected to the original bond of childhood simply by remembering the past.

The novel’s first image responds to Jim’s description of his first sight of Ántonia and her family: In the red glow from the fire-box, a group of people stood huddled together on the platform, encumbered by bundles and boxes. I knew this must be the immigrant family the conductor had told us about. The woman wore a fringed shawl tied over her head, and she carried a little tin trunk in her arms, hugging it as if it were a baby. There was an old man, tall and stooped. Two half-grown boys and a girl stood holding oilcloth bundles, and a little girl clung to her mother’s skirts. (5–6) The picture gives us the indelible first impression of Ántonia in Jim’s visual memory. Jim’s verbal picture includes details that have been “sacrificed” in Benda’s drawing. The figures in the image are gathered close into a composition that reveals little of the subjects’ individual marks. Their identities are obscured by the way Benda has positioned his figures; Mr. and Mrs. Shimerda look down, Ambrosch and Marek are turned away, Yulka is barely visible. Only Ántonia is facing the viewer/reader, and all of the family members’ features are crudely drawn and deeply shadowed. The outlines of the total group form the most identifiable shape in the image. As a visual introduction to his Nebraska journey, it stands as a dark marker of the abrupt transformation that Jim, Jake, and the Shimerdas are experiencing, and of the state of mourning (for the security of family, the certainty of primary emotional bonds) the newly orphaned Jim is in. The sight at once reassures as a family, but carries hints of foreboding in its massed black shapes. Attempting to recall his first sight of the Shimerda family from the distance of thirty-plus years, he summons it from his memory supported by images of childhood. These provide the visual template for the appearance of the Shimerdas in his mind. Murphy’s insights on the influence of genre painting and luminism in Cather’s descriptive prose are quite well founded; however, the first generation of viewer/readers of Cather’s novel are more likely to have made a similar association with popular media such as the woodcut. In this first image of family—a primary bond that Jim has lost—Benda has sounded the complex chords of the novel’s emotional movement.

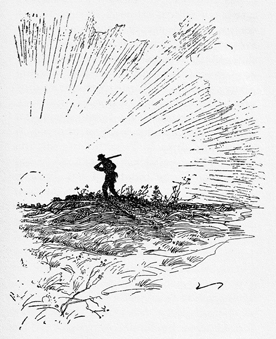

Fig. 4. W. T. Benda, Mr. Shimerda, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 4. W. T. Benda, Mr. Shimerda, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

The second image is of Mr. Shimerda walking home at sunset; the third is of an old Bohemian woman gathering mushrooms. In sequence, the pair pictures Jim’s earlier memories of coming to know Ántonia’s family. In figure 4, Benda has answered Cather’s verbal text with a continuing element of visual warning. The silhouetted figure of Ántonia’s papa is poised in alignment with the sun’s descent, his inexorably downward motion at odds with Jim’s reading of each prairie sunset as a “triumphant ending, like a glorious hero’s death” (39). The tilt of Mr. Shimerda’s head and the slump of his back speak more to his daughter’s worries than to Jim’s heroic romanticism. Despite the fat silhouetting of the figure, the bag of rabbits is just visible, suggesting that the father’s doubts about providing for his family are profound and intractable.

Brake and Demoor note that the development of photography in the early nineteenth century was not met with significant consumer approval; the woodcut remained the most popular illustration for news and serialized literature until the end of the century (2–3). According to James Mussell in “Science and the Timeliness of Reproduced Photographs in the Late Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press,” photographs began to appear more frequently in the later nineteenth century press, when reproductive technologies and cheap, high-quality paper became available (204). This second draw- ing captures a written description of a moving image by referencing early photographic images. These and early motion studies, such as those of Muybridge in the 1870s, position the human subject against a background of light, resulting in a darkened subject. The effect creates a contrast between the uniform quality of the light in the background and the shaded figure in the foreground.

Benda seems to have exploited the darkened human figures in the photos to suggest their common visual ground with the woodcut’s fat, dark shapes. His image also suggests a sense of despair surrounding Jim’s memory of Ántonia’s father. He is pictured as walking under a fanned series of hatch marks meant to suggest the fading light, simultaneously referring to actual early photographs of men on the plains and suggesting the way those images would have looked if they had been reproduced as woodcuts.

Fig. 5. W. T. Benda, Bohemian Woman, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 5. W. T. Benda, Bohemian Woman, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Benda’s third illustration conveys an impression of Jim’s imagined Bohemian woman gathering mushrooms in a forest. Jim remembers the “little brown chips that looked like the shavings of some root” (76). Although he readily tastes one, Jim is unable to summon any American analog for this strange food. Its unfamiliar taste, though, summons the verbal image to Jim’s mind of a type of person and a place that he has never in his life beheld, but which he shares as part of his narrative of memory: “I never got over the strange taste; though it was many years before I knew that those little brown shavings, which the Shimerdas had brought so far and treasured so jealously, were dried mushrooms. They had been gathered, probably, in some deep Bohemian forest” (77).

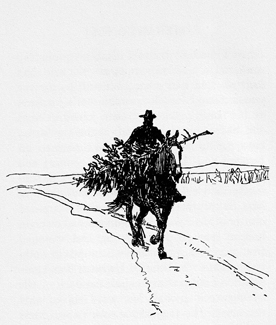

Fig. 6. W. T. Benda, Jake, courtesy of the Willa

Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National Willa

Cather Center.

Fig. 6. W. T. Benda, Jake, courtesy of the Willa

Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National Willa

Cather Center.

Because the alien look and taste of the mushrooms stimulates this memory, it is then formed in Jim’s imagination as a verbal icon. In this picture, details such as the mushrooms in the foreground and the headscarf of the woman who is gathering suggest a familiarity to Jim: he has seen American mushrooms and has noticed that Mrs. Shimerda commonly wears a headscarf. The figure’s face, like those in the first two images, is obscured, perhaps by Jim’s inability to call a similar face to mind. But he probably also borrows her bent form from that of Mrs. Shimerda, an older immigrant woman whom he has been studying since his arrival.

The novel’s first three images thus emphasize the strange, somewhat bleak, and portentous sights of Nebraska that Jim remembers or imagines. These are succeeded in the fourth image by a much more familiar American cultural figure and landscape—the cowboy riding his horse on a winter prairie. Benda’s image is reassuringly rooted in popular photographs of men in the West, such as those that Cather herself possessed, astride or standing near their horses. The little fr tree is likewise immediately intelligible to Cather’s readers as a symbolic object associated with utterly familiar historical and religious narratives. This image creates a hopeful note of comfort in the novel, as Jim becomes more familiar with his new life on the plains. It redirects the visual narrative, being the first of a new embedded sequence of three pictures that speak to the happy middle period of Jim’s youth, as he becomes accustomed to life with his grandparents and more attached to Ántonia. Through the door opened by the image of Jake, the two images that follow it answer Cather’s written evocation of these halcyon days.

Like the image of Mr. Shimerda walking home, the drawing of Jake bringing the little fr tree to Jim is likely constructed in part from his having seen early explorations of the photographic medium. The sense of motion in the figure and the dark contrast of the visual subject against the sky’s light evoke such a source, both for Benda’s public construction and for Jim’s private one. Here, however, Benda uses the positive pictorial symbolism of forward movement, suggesting Jim’s rising spirits in his new home. Jim sees Jake and the horse coming toward him with the Christmas tree that his new family had provided, while in Jim’s earlier memory the disconsolate Mr. Shimerda retreats from Jim, becoming ever more isolated.

Fig. 7. W. T. Benda, Ántonia and Her Team, courtesy

of the Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the

National Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 7. W. T. Benda, Ántonia and Her Team, courtesy

of the Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the

National Willa Cather Center.

Benda’s fifth drawing also signals Jim’s increasingly positive emotional state. Here we have the image of Ántonia returning home with her team of horses. Like Jake, Ántonia has been long awaited; the sight of this young woman is, for Jim, a promise fulfilled. The image responds to Jim’s memory of Ántonia coming toward him from the fields, first from afar and then close up: “When the sun was dropping low, Ántonia came up the big south draw with her team. . . . now she was a tall, strong young girl” (117). Here, the foregrounded graphic elements of line and mass, etched sharply into the simply articulated background, reference the woodcut. She wore the boots her father had so thoughtfully taken of before he shot himself, and his old fur cap. . . . She kept her sleeves rolled up all day, and her arms and throat were burned as brown as a sailor’s. Her neck came up strongly out of her shoulders, like the bole of a tree out of the turf. One sees that draught-horse neck among the peasant women in all old countries. (117) Given these last details, one can understand why Murphy sees Jean-François Millet’s peasant women as an image source for Jim’s close-up description of Ántonia (Murphy 45). Yet Millet’s paintings are full of the subtle color tonalities. The specific visualizations of period clothing and human postures embody traditional forms of realism. While Cather has obviously sourced her verbal description partly in images such as Millet’s, Benda’s more crudely developed, woodcut-like image of Ántonia with her team of horses refers again to the popular medium that would more likely inform Jim’s mental picture of her. Despite Cather’s allusion to the old-country peasant woman’s appearance, Jim’s memory of Ántonia communicates a strikingly different picture to our minds, one of a pragmatic young woman who works hard to sustain her family farm, who not only “can work like mans now,” but doesn’t mind wearing men’s clothing if it is useful to her (118).

Benda shapes his image of Ántonia driving her horses home across the prairie as an answer to Jim’s narrative. The composition of the image foregrounds her; there is no mistaking that the horse team is being ably managed by a female. Though her headscarf reminds readers of her status as a foreign other, this commanding image of Ántonia as a team driver shows us that her life has, like Jim’s, become a fulfilling one. In this image, Benda pictures her transformation from a Bohemian girl who would never have been allowed to drive a horse team into “a woman of toil,” capable of making her contribution to the American West.

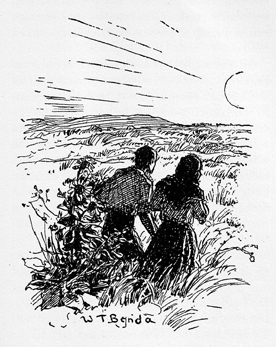

The sixth picture visualizes Jim’s memory of his restored friendship with Ántonia, with whom, following the springtime feud between their families, he is reunited: “Each morning, while the dew was still on the grass, Ántonia went with me up to the garden to get early vegetables for dinner. Grandmother made her wear a sunbonnet, but as soon as we reached the garden she threw it on the grass and let her hair fly in the breeze” (132–33).

Fig. 8. W. T. Benda, Ántonia and Jim, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 8. W. T. Benda, Ántonia and Jim, courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National

Willa Cather Center.

The illustration draws on the Barbizon school’s simple showcasing of the pictorial subject (Murphy 46). Despite its origins in a particular compositional tradition, however, Benda’s image once more gives the viewer/reader less detail in a more concentrated, more graphic assemblage of forms; here again Benda works in the style of the woodcut medium, realizing the image by adapting compositional traditions of the Barbizon school. The simpler, more emotional rendering of the figures of Jim and Ántonia—the last that pictures their happy closeness—shares Jim’s open-hearted joy in his friend. Jim’s memory about Ántonia ’s head covering, however, is returned by Benda’s image of Ántonia, her face invisible, her head covered or partially so by an obscure shape that looks more like a scarf than a sunbonnet. The effect of this detail in the visual narrative speaks to the complexity of Ántonia’s life transformation: she is poised between girlhood and womanhood, immigrant type and pioneer icon. Both young friends, now so happily bonded, are on the point of change and separation, reflected more elegiacally in Benda’s drawing than in Cather’s description. As Jim identifies ever more closely with her, Ántonia evolves from dutiful immigrant into an independent, capable young Czech woman transplanted to the American West. At the heart of their friendship, Jim recognizes her native strength and has valorized what was once incomprehensibly foreign in her.

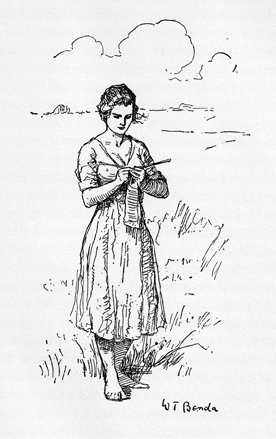

Transplanted to Black Hawk, Jim, Lena, and Ántonia share a more intense adventure than the innocent meetings that their country childhood afforded, trying out their emerging adult identities in the home of the Harlings, the downtown, and especially in the dance tent on Saturday nights. Like the six pictures that go before it, the portrait of Lena is steeped in Jim’s imaginings: in this case, Benda clearly visualizes Jim’s sexual longings in the often-noted details of Lena’s dishabille. Whenever we rode over in that direction we saw her out among her cattle, bareheaded and barefooted, scantily dressed in tattered clothing, always knitting as she watched her herd. . . . Her yellow hair was burned to a ruddy thatch on her head; but her legs and arms, curiously enough, in spite of constant exposure to the sun, kept a miraculous whiteness which somehow made her seem more undressed than other girls who went scantily clad. (160)

In Jim’s sight, Lena becomes a focus. Put simply, she lures him—into a waltz, into preconscious sexual fantasy, into anything that feels, hypnotically, like a “fated return” (216). Adapted from traditions of portraiture, Benda’s image places Lena at the front and center of the frame. It figures a nearly literal impression of Jim’s memory of her, even to the inclusion of her knitting work. This vision sets up an interesting tension between Benda’s impression of Jim’s common memory of Lena and his dream narration toward the end of book 2, when Lena’s knitting needles have been transformed in Jim’s dream into a reaping hook that might symbolize the break from child to adult consciousness that will separate Jim from Black Hawk and his Ántonia.

Fig. 9. W. T. Benda, Lena, courtesy of the Willa

Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National Willa

Cather Center.

Fig. 9. W. T. Benda, Lena, courtesy of the Willa

Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the National Willa

Cather Center.

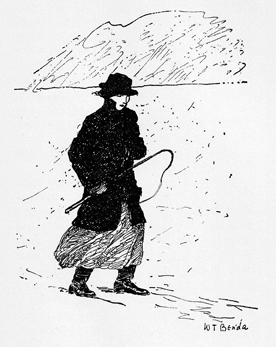

Fig. 10. W. T. Benda, Ántonia in Winter, courtesy of

the Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the

National Willa Cather Center.

Fig. 10. W. T. Benda, Ántonia in Winter, courtesy of

the Willa Cather Foundation Special Collections & Archive at the

National Willa Cather Center.

If Jim’s new focus on Lena has inserted space between him and Ántonia, Benda’s image of Ántonia walking home in winter at the end of her first pregnancy communicates an even wider distance between the two friends. The drawing has its source in a strong verbal icon, since Jim relies for this memory-as-image on the Widow Steavens’s sharing her memory of the sight with him. Thus Benda constructs an impression of Jim’s memory-of-a-memory, an appropriation of what the widow saw and felt, to visualize Jim’s interior sight.“Late in the afternoon I saw Ántonia driving her cattle homeward across the hill. The snow was flying round her and she bent to face it, looking more lonesome-like to me than usual” (308). The last illustration of Ántonia is a representation of her trudging dispiritedly home in the cold as the Widow Steavens recalls it, but it is not a sight that Jim has ever seen. He must invoke it from the details of what he is told, constructing an image of her in his mind as he constructed his verbal icon of the old Bohemian woman.

In the “portraits” of Lena and Ántonia , Benda shares his impressions of Jim’s interior visions. The sparse backgrounds here make way for the viewer’s focus on Lena and Ántonia to replicate Jim’s psycho-sexual and psycho-emotional focus on each of them, respectively. In the formal details of Lena’s body and dress, Benda captures the emergent adult sexuality that is at the heart of Jim’s verbal image of her. Benda’s portrayal of Ántonia stands in high contrast in this regard: her body is fully covered, not only by her clothing itself but by the double layer of gendered signifiers she wears. These layers, of course, interrupt any direct sexual preoccupations that might be a part of Jim’s inner vision of her, but also strongly signify the rising value of other aspects of her character within his mind. Each is pictured as an immigrant woman. Lena’s skimpy rags and Ántonia’s men’s outerwear are explained by the necessities of pioneer life, especially for those immigrant families—like the Shimerdas and the Lingards—who had to make their livings on the prairie from scratch. Benda’s handling of Lena’s head, remembered by Jim as frequently bare, suggests ambiguously a type of informal headgear, such as a bandana, a detail that links her to the immigrant women in the other illustrations. Jim’s attraction lifts her from the status of a member of the “unassimilable alien hordes” to the “visibly feminine” and thus to the status of an object of desire (Banta 109). The gender mix of Ántonia’s clothes, especially the hat settled low over her head, speaks potently of what her meaning has become at this point to Jim: a woman who redefines the feminine, a “soul which never concedes defeat” and who binds Jim to her above all (Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen, qtd. in Banta 101–2). Benda invokes Jim’s elevation of Ántonia in the gravity of his impression, which features her stately determined posture, enlarged by the weighty outlines of her dark winter attire. Benda’s visual narrative, in Boyeson’s words, “lif[s] the character to a higher plane,” capturing the fact that the pregnant Ántonia , who still works the land like a man, has become an icon of regeneracy who transcends the feminine to encompass the devoted cultivation and stewardship that is the heroic legacy of the frontier.

Cather’s figurative language works to suggest how Ántonia lingers in Jim’s memory. Similarly Benda’s images suggest how Ántonia becomes a figure shaped by Jim’s memories of her. Other picture writing in the novel, such as the Indian circle of book 1, chapter 9, and sun and moon balancing in the sky in book 4, chapter 4, answer Cather’s image of the encircled plow. The closing image of Ántonia’s children scrambling out of the fruit cave in book 5 is, like the plow, an iconic picture in a circular frame. Jim’s visit to his friend is cluttered with references to pictures, actual and remembered, but Cather’s images of the plow magnifed against the setting sun in book 2 and of the children emerging from the cave in book 5 serve as a pair, framing the narrative of the two friends’ final passage into full adulthood. This later image also obliquely echoes Benda’s first illustration of Ántonia with her family, thereby suggesting the effect of bookends for the entire narrative. We were standing outside talking, when they all came running up the steps together, big and little, tow heads and gold heads and brown, and flashing little naked legs; a veritable explosion of life out of the dark cave into the sunlight. It made me dizzy for a moment. (328) Both word pictures feature encircled images that derive their power from the power of light: the sun descends, magnifying the plough’s silhouette, and the children spill across the cave’s barrier of darkness into the sun where Jim and Ántonia await them. Both pictures evoke a deep primary reaction, immediate and physical, from Jim. Neither one contains the figure of Ántonia, although she is a witness to both sights. For Jim, however, these may be screen memories: in the case of the plough at sunset, for his immanent parting from her, or in the case of the fruit cave, for his awareness of her as a sexual maternal body. Nonetheless, each one functions to illuminate the way that she gives meaning not only to his passage from child to adult but also to the plains’ passage from grassy wilderness to abundant farmland: Ántonia had always been one to leave images in the mind . . . that grew stronger with time. In my memory, there was a succession of such pictures . . . like the old woodcuts of one’s first primer. . . . She lent herself to immemorial human attitudes which we recognize by instinct as universal and true. (342) Watching the last sunset on his visit to a disappointingly changed Black Hawk, Jim traces “what a little circle man’s experience is” and through his memories of Ántonia knows her to be not just the girl he grew up with and the young woman he adored but a regenerate icon, binding them both, as surely as memory, to the heroic past of the American West.“Some memories are realities and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again” (318).

As graphemic systems are used for the written communication of shared cultural understandings, Benda’s visual and Cather’s verbal images form a bitextual graphemic system to communicate an elevated cultural icon of American pioneer womanhood. From what we know of Cather’s own Nebraska childhood, certain women, like Annie Pavelka and Carrie Miner, whom she admired as a child in Red Cloud and with whom she continued in close friendship throughout her life, informed Cather’s vision of her character, Ántonia, as the representation of a new female type that transcends social hierarchies. Cather’s picture writing, deployed masterfully with Benda through the popular visual imagery of late nineteenth-century America, gives to the central figure of her novel an enduring power.