From Cather Studies Volume 13

The Boxer Rebellion, Pittsburgh's Missionary Crisis, and "The Conversion of Sum Loo"

Sweeping across northern China like a prairie fire during the summer of 1900, the Boxer Rebellion became a story no journalist of Willa Cather’s ambition could ignore.[1] With more than two dozen missionaries stationed in districts where the Boxers were determined to kill or expel all foreigners, Pittsburgh congregations were justifiably worried. That summer, Cather published three pieces about the rebellion in Pittsburgh’s new arts and opinion weekly, The Library, writings that confirm her opposition to Christian missionaries proselytizing the Chinese, a belief formed during her teen years in Red Cloud.

Scholars have explored her contributions to Pittsburgh’s Home Monthly as both writer and editor in a number of articles, dissertations, and book chapters.[2] Her role at The Library, by contrast, remains little studied. This essay will examine Cather’s writings about the Boxers in the context of an extended debate over Chinese missions in The Library and the city press. More than two decades later, individuals who linked Pittsburgh with north China at the time of the uprising inform her depictions of Enid Wheeler and Arthur Weldon in One of Ours and shape key passages of that novel. Enid’s father, Jason Royce, approximates Cather’s mature estimate of the missionary enterprise when he tells Claude,“I don’t believe in one people trying to force their ways or their religion on another . . . [China] seems like a long way to go to hunt for trouble, don’t it?” (One of Ours 292). I argue that Cather reached this conclusion as early as August 1900, when “The Conversion of Sum Loo,” her final contribution to The Library, charged that the missionaries of Pittsburgh deserved much of the trouble they received at the hands of the Boxers.

The Boxer Rebellion grew out of a number of environmental and cultural stressors. Catastrophic floods and a three-year drought had left the farmers of Shantung Province facing starvation. Thousands more lost their livelihoods when the new railway built by the Germans coopted freight traditionally carried by carters and boatmen (Silbey 39). Among foreigners in Shantung, the Germans were particularly unwelcome because Kaiser Wilhelm II had ordered his subjects to impress on the Chinese the superiority of Teutonic civilization (Silbey 14). Having claimed Shantung as a “sphere of influence” in 1897, the Germans, backed by their formidable navy, acted as if they already owned the country. German diplomats, railroad engineers, and missionaries bullied officials, from the Manchu elite in Peking down to local magistrates. Railroad engineers inundated farm fields and desecrated graveyards and holy sites, ignoring local protests. With one crop killed in the fields and no rain to grow another, the people of Shantung were left hungry, idle, and increasingly resentful of foreign impositions on their land and traditions.

At first, the people’s anger was directed toward Chinese converts to Christianity, but on the last night of 1899 it was vented on a European. According to historian Norman Cliff, the first Western casualty of the rebellion was twenty-four-year-old Sidney Brooks, a novice working for the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. On 31 December, after dining with his sister in Tiana, Shantung Province, “[Brooks] was waylaid by a band of young toughs. He tried to run ahead of them, but men on horseback chased after him, and he was beheaded.” Brooks’s murder and mutilation was attributed to a secret society called the “Righteous and Harmonious Fists” or the “Big Knives.” Western journalists dubbed the group Boxers for the callisthenic exercises adherents were told would equip them with “iron shirts” impervious to bullets (Silbey 7). Though armed with little more than knives, swords, and tridents, the Boxers became a formidable militia, murdering Chinese Christians and missionaries, burning churches and railroad stations, and routing professionally trained European troops. The Boxers’ promises to drive the foreigners from Chinese soil, restore stolen lands, and propitiate the ancestors so that the rains would commence appealed to a hungry and desperate people (Silbey 74).

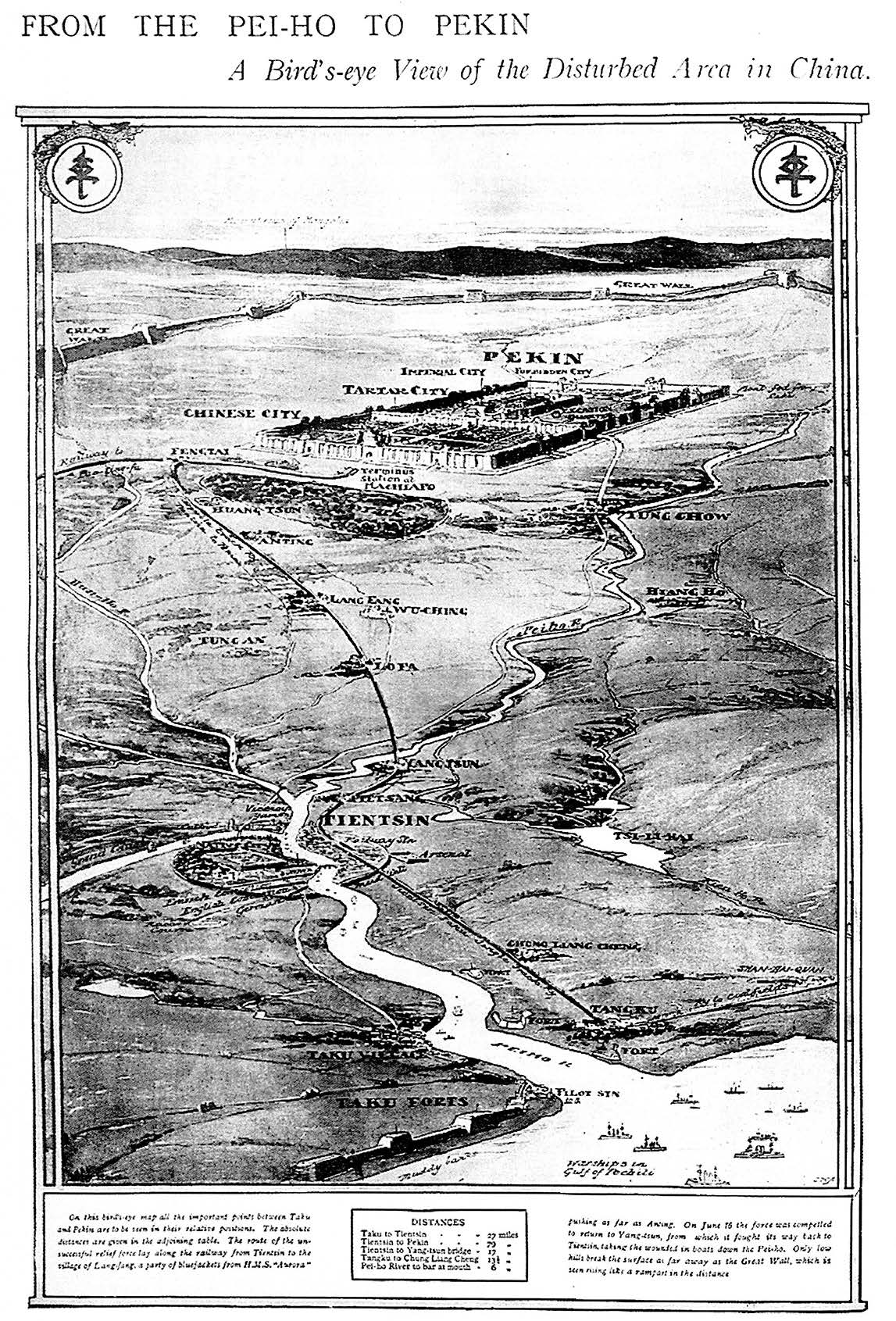

Initially, Dowager Empress Cixi denounced Boxerism, but in mid-June, when German and Japanese diplomats were assassinated in Peking, it became clear that Cixi and her nephew, Prince Tuan, had formed a secret alliance with the rebels. When the railway was sabotaged by the Boxers in early June, trapping foreign nationals inland, the Allied Powers grew alarmed and ordered their gunboats at the mouth of the Han River to reduce the Taku forts in preparation for landing troops (see figure 3.1). The conflict escalated when thousands of Boxers, supported by Imperial Guards, besieged the Foreign Legation Quarter of Peking, within whose walls five hundred Western and Japanese civilians, four hundred marines, and twenty-eight hundred Chinese Christians sought refuge. On 10 June, the Allies launched an Expeditionary Force of nearly two thousand men, led by British Vice Admiral Edward Seymour, but guerilla attacks were so relentless that Seymour was forced to retreat and await reinforcements. Allied arms and strategy eventually prevailed, but before hostilities ceased in September, one hundred thousand Chinese combatants and civilians and two hundred and fifty foreign missionaries had been killed. Atrocities abounded on both sides. Libraries and cathedrals were burned by the Boxers during the siege of the legations, and the Allied army responded by thoroughly sacking Peking, earning international condemnation for pillage, rape, and murder of Chinese civilians.

Halfway around the world, in Pittsburgh, a smart new current-events magazine named

The Library debuted on 10 March 1900.  Fig. 3.1. An illustration, originally from Leslie’s

Illustrated Weekly, ca. 1900, shows the rail line by which the

Seymour Expedition tried to reach the Foreign Legations at Peking. Seymour’s

mission was stymied by Boxers tearing up the rails between the city of

Tientsin and the village of Lang Fang, at center. Similar illustrations in

the city papers taught Pittsburghers the geopolitics of northern China

(Martin 9). Freshly detached from the Pittsburgh Leader,

Cather began contributing with the magazine’s second issue. William Curtin doubts

she was on staff, but he judges she had an “inside track,” meaning that managing

editor Ewan Macpherson would publish anything she and George Seibel submitted (World and the Parish 753; Seibel 205). Born in Jamaica and

educated at Stonyhurst, the premier Jesuit college in England, Macpherson, like

Cather, was a cultural outsider and an outspoken critic of Pittsburgh

Presbyterianism (Lewis 147; Seibel 205). Several years after Cather made fun of

local divines protesting classical music concerts on Sunday, Macpherson mocked the

same cadre for imposing their Sabbath on the entire city (Cather, “The Passing

Show,” 17 January 1897, in World and the Parish 2: 507;

Macpher-son, “For Our Country’s Good,” The Library, 11

August 1900, 13).

Fig. 3.1. An illustration, originally from Leslie’s

Illustrated Weekly, ca. 1900, shows the rail line by which the

Seymour Expedition tried to reach the Foreign Legations at Peking. Seymour’s

mission was stymied by Boxers tearing up the rails between the city of

Tientsin and the village of Lang Fang, at center. Similar illustrations in

the city papers taught Pittsburghers the geopolitics of northern China

(Martin 9). Freshly detached from the Pittsburgh Leader,

Cather began contributing with the magazine’s second issue. William Curtin doubts

she was on staff, but he judges she had an “inside track,” meaning that managing

editor Ewan Macpherson would publish anything she and George Seibel submitted (World and the Parish 753; Seibel 205). Born in Jamaica and

educated at Stonyhurst, the premier Jesuit college in England, Macpherson, like

Cather, was a cultural outsider and an outspoken critic of Pittsburgh

Presbyterianism (Lewis 147; Seibel 205). Several years after Cather made fun of

local divines protesting classical music concerts on Sunday, Macpherson mocked the

same cadre for imposing their Sabbath on the entire city (Cather, “The Passing

Show,” 17 January 1897, in World and the Parish 2: 507;

Macpher-son, “For Our Country’s Good,” The Library, 11

August 1900, 13).

Initially at least, both Macpherson and Cather sided with the Boxers. In the 14 July Library, Macpherson exclaimed with mock horror, “What a villainous horde of ruffians those Boxers must be” and then proceeded to demonstrate that Americans would behave exactly like Chinese Boxers if faced with similar threats to their liberty. In another column, he introduced his favorite figure of speech—analogy—proclaiming, “Now it is always good to put oneself in the mind of others if this can be done.” While Pittsburgh’s Independence Day fireworks were yet a recent memory, Macpherson offered, in his Library article “For Our Country’s Good,” a thought experiment comparing the Chinese custom of ancestor worship to America’s veneration of its Founding Fathers: There seems to me to be a striking analogy between [Chinese ancestral rites] and certain celebrations in which Americans delight. And suppose that Chinese settlers should come into America in large numbers and all smile pityingly at our idolatrous fireworks, whereby we think we honor the memory of a number of persons and deeds long since dead and done—suppose they jeered at Washington’s Birthday and called Thanksgiving Day a piece of antiquated poppycock—would there not be here and there an American Boxer to deal with them? And suppose they had a fleet, stronger than ours, scattered up and down our coast, and perhaps they were largely represented at Washington and there constantly bulldozed the President, pointing out to him that American ideas were preposterous and threatening him with their formidable displeasure if he did not become enlightened with light from China—might not a Ku Klux Klan, or a Vigilance Committee, or a Whitecap Society arise even in Washington? But that would be an American patriotic movement, not a movement of Chinese Boxers, who, as I have said above, are a villainous horde of ruffians. (14 July 1900) Macpherson’s analogies probably amused Cather, but more importantly they influenced the way she understood the Boxer movement, for several weeks later, adopting the voice of Pittsburgh Cantonese importer “Lee Chin,” she, too, imagined the tables turned. In “A Chinese View of the Chinese Situation,” she envisioned China joining America’s former colonial powers to partition the United States: “Suppose China should decide she wanted San Francisco and take it, and France should take New Orleans and the Mississippi, and Germany New York; what would your people do?” (17). Her appeal to readers’ historical imagination is a clear echo of Macpherson’s assertion that American patriots would not tolerate the indignities imposed by the Allied Powers. Cather found Macpherson’s editorials refreshingly combative and The Library’s pay scale agreeable.[3] Most of the remaining twenty-five numbers contain a poem or short story with her byline and a second piece signed with a pseudonym (World and the Parish 2: 754; Seibel 205).

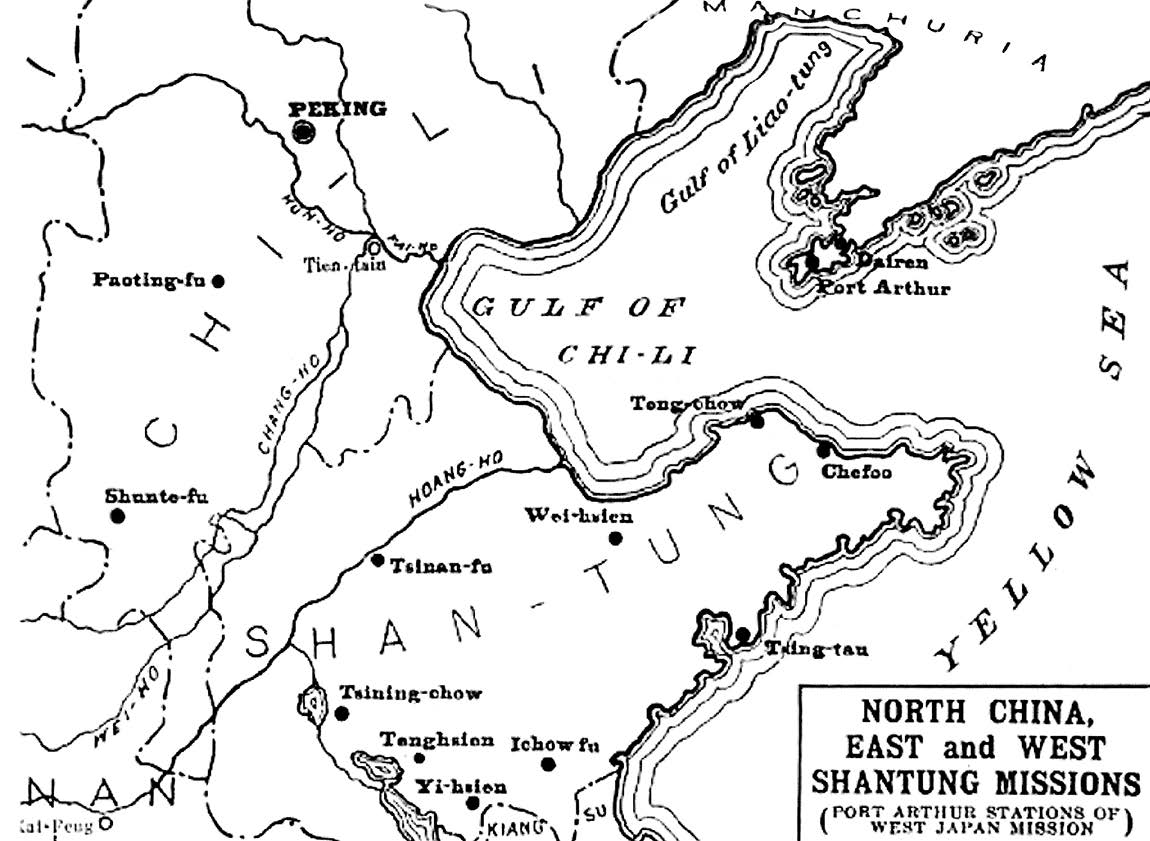

Not all contributors to The Library sympathized with the Boxers. Defending the foreign missions were the coeditors of the “Pittsburgh People and Doings” department,“E.O.D.” and “C.W.S.”[4] Filling their two pages each week with photos and letters from local missionaries, most often they used the correspondence of Charlotte Elizabeth Hawes, a member of the Nevin publishing family. Hawes had for the past three years taught women’s Bible and kindergarten classes from Wei Hsien mission, the oldest and largest Presbyterian station in north China (see figure 3.2). Wei Hsien was largely financed by Pittsburghers, as reflected in its boys’ high school, Point Breeze Academy, named for the elite East End enclave where lived Frick, Carnegie, and fellow industrialists. In addition to the boys’ high school, the high perimeter wall of Wei Hsien contained ten missionary residences, a girls’ high school, a kindergarten, two hospitals and dispensaries, two churches, and a chapel (Presbyterian Church).

Fig. 3.2. A map of the Presbyterian missions in north China shows Wei Hsien’s

central location, about two hundred miles from the coast. Source: Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Foreign

Missions of the Presbyterian Church of the United States, May 1901, p. 111,

Google Books.

Fig. 3.2. A map of the Presbyterian missions in north China shows Wei Hsien’s

central location, about two hundred miles from the coast. Source: Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Foreign

Missions of the Presbyterian Church of the United States, May 1901, p. 111,

Google Books.

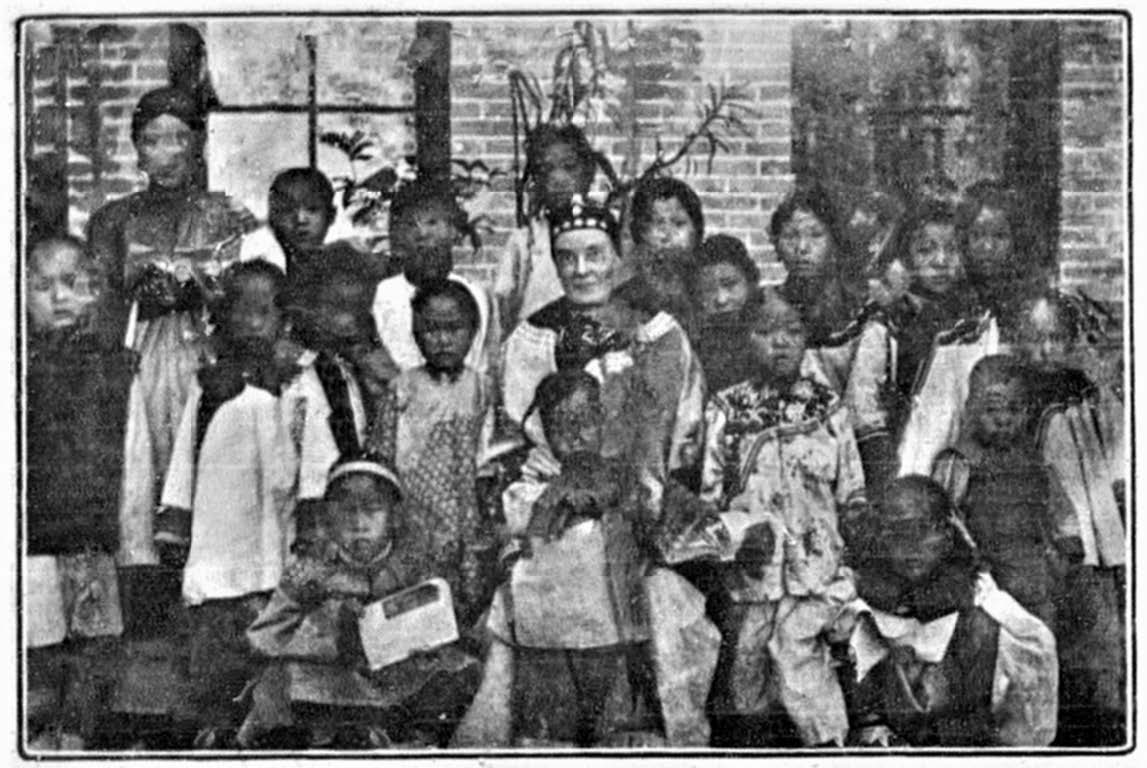

Charlotte Hawes’s correspondence was supplied by her elder sister, Mrs. Eleanor (Nellie) Nevin, the widow of John I. Nevin, co-founder of the Pittsburgh Leader.[5] Having worked for three years as assistant telegraph news editor of the Leader, Cather could not have helped knowing Mrs. Nevin, nor could she have missed reading Miss Hawes’s dispatches from Wei Hsien. The 30 June issue of The Library, for example, placed Cather’s own poem, “Broncho Bill’s Valedictory” opposite two photographs of “Miss Hawes and Her Chinese Lambs” and a seven-inch selection from one of Charlotte’s letters (see figure 3.3).

Fig. 3.3. One of two photographs of Charlotte Hawes’s kindergarten students

that appeared in the 30 June 1900 issue of The Library

(6–7). The setting appears to be the Wei Hsien mission.

Fig. 3.3. One of two photographs of Charlotte Hawes’s kindergarten students

that appeared in the 30 June 1900 issue of The Library

(6–7). The setting appears to be the Wei Hsien mission.

In this particular excerpt, Charlotte assured her sister, “We are all well here and around Wei Hsien is peaceful, so don’t worry about me. I can go anywhere except in an easterly district, which I have never visited anyhow” (7). But rioting outpaced her letters from China. On 25 June, five days before these assurances appeared in the 30 June Library, a mob of about five hundred burned Wei Hsien. Informed by cable of the attack on 26 June, churchgoing Pittsburgh obsessed about the three missionaries who had not yet evacuated—the Rev. Frank Chalfant, Miss Emma F. Boughton of Buffalo, and Miss Charlotte Hawes. Their fate would not be known stateside for eleven days.

Cather tapped Pittsburgh’s interest in the Boxer Rebellion thrice. Her first effort, co-written with her brother Douglass, was “The Affair at Grover Station,” serialized in The Library’s 16 and 23 June issues. The Cather siblings imbued Freymark, their half-Chinese, half-French villain, with stereotypes used by newspaper journalists to malign the Boxers. According to the focal character Terrapin Rogers, Freymark’s Chinese blood “explained everything” nefarious about him (342). He is a “rat eater” who, although just thirty, possesses the “yellow, wrinkled hands of an old man.” He is addicted to gambling, has trafficked opium in London, and proves a “clam-blooded” killer who, after shooting Larry Donovan fatally through the mouth, sadistically shot Larry’s spaniel, Duke, through the side (339–43). The story probably dates from early June 1900, when Willa and Douglass would have been reading in newspapers about the sabotage of rail lines and arson of railroad stations around the city of Tientsin. But it is curious that Freymark’s revenge is accomplished using an insider’s knowledge of railroad logistics and telegraphy, for in her own journalism, Cather insisted that the Chinese psyche could not adapt to European modernity.[6] Presumably, Freymark’s paternal blood—his father was a French military officer—countered the “amphibious” blood of his Chinese slave-girl mother (343) so that he could exploit the railroad’s flaws in security.

Mildred Bennett finds it remarkable that barely a month after the Cather siblings subjected Freymark to racist invective in “The Affair at Grover Station,” Cather treated Pittsburgh Cantonese importer Yee Chin with greater sympathy when asking him about the causes of the Boxer Rebellion (Early Short Stories 245). Although Bennett and others have assumed “A Chinese View of the Chinese Situation” is a legitimate interview with Yee, I conclude from its timing and many inaccuracies that Cather faked the encounter (Recovering the Extra-Literary 164–209). Writing as her man-about-town persona Henry Nicklemann, Cather claimed that “when I stopped at [Yee’s] shop last Friday afternoon he was busy making preparations to take his wife to San Francisco” because “loneliness, lack of exercise, and homesickness [had] brought on a [life-threatening] mental disorder.” Cather offers no reason why Yee would pause in the midst of such an emergency to sit down with a reporter he did not know. The day before the presumed “interview,” both the morning Pittsburgh Gazette-Times and the afternoon Pittsburgh Press had announced that Mrs. Yee had suffered a nervous breakdown. Both papers noted that the Yees would depart the next day for San Francisco in the hope that some time with her family would restore Mrs. Yee’s mental equilibrium (“Chinese Woman May Be Insane” 20 July 1900; “Going to California: The Wife of Yee Chin is Suffering from Mental Disease” 20 July 1900). But internal evidence suggests Cather began writing only after the couple were safely on their way to California on 21 July.[7]

Cather-as-Nicklemann found Yee (or as she misnamed him,“Lee” Chin) reluctant to talk about the unrest in China, yet with little prompting she extracted a suspiciously coherent explication of the Boxer conflict. “Lee” Chin claimed the common Chinese did not care who ruled them as long as taxes were bearable and their nominal rulers left them alone. The current empress was Manchu, one of the Tatar people who had ruled the Chinese for generations after wars of corresponding length. Cather expounded on the history of the Qing Dynasty, facts near at hand from her Leader work embellishing cabled news. The Chinese people cared little for the Manchus, and the Manchus even less for the people they ruled, but Empress Cixi was determined to remain in power, even if doing so meant appeasing the Western powers with concessions of land. It was this “sacrifice of land to foreigners for purposes that [they] cannot understand” that had turned the common Chinese against Europeans. The Boxer insurgency was less a religious confrontation than a territorial struggle, not a revolt against Christianity but against Western imperialism. The attacks upon missionaries puzzled “Lee”: the common Chinese did not dislike missionaries, and “there was no general revolt when European missionaries went to China.” Thirty years before, when “Lee” lived in China,“all missionaries who were gentlemen were well liked, and all who were not were detested.” What the Chinese could not abide was the greed of the European politicians, their intolerance of other religions, and their attacks on the age-old practices that formed the very fabric of Chinese culture. The Chinese commoner was “wedded to his traditions and institutions, and with these the [Manchus] have never interfered, though the Europeans have” (Zhu and Bintrim 4).

Under pressure from the European powers, Cixi “[began] cutting off slices of the Empire and giving them to Europe”; consequently, the peasants were “maddened at the prospect of losing the land they have held since two thousand years before Christ.” Germany, particularly, had used the killings of Europeans as pretense for extorting more territory. The common Chinese, meanwhile, suspected that “the railroad, the telegraph, [and] Christianity were only the forerunners of this wholesale theft of land—means to facilitate the division of the Empire among Western nations,” Cather wrote in “A Chinese View.”

Two weeks after this “interview,” Cather placed in The Library’s 11 August issue a third, clearly fictional commentary, blending her experience of real missionaries in Red Cloud and Pittsburgh and her imaginings about those in Shantung. Advertised on the masthead as “A Sketch of Native Chinese Life” and ostensibly set in San Francisco, “The Conversion of Sum Loo” had roots elsewhere. According to Mildred Bennett, Cather’s aversion to Chinese missions began in Red Cloud. A young townswoman she particularly disliked traveled with her husband, physician L. D. Denny, to Peking in 1884, where the two briefly served the Methodist mission. The Dennys wrote “effusive letters home that were published in the local newspaper” but before the year was out, the couple came home “with a large collection of curios, linens, and objets d’art,” which they took on the lecture circuit. “Willa suspected [Laura Denny] had acquired these treasures by some sort of mis-dealing with the natives,” Bennett continues, and “could not endure the exploitation of possessions and experiences when this woman charged for her lectures.” Cather’s aversion to the Dennys’ cultural appropriation, concludes Bennett, became a conviction that “the ancient civilization of China could get along quite well without our . . . interference” (World of Willa Cather 136).

Though Willa probably did not collaborate with Douglass on “The Conversion of Sum Loo,” she seems to have had her siblings in mind as a target audience.[8] Just two missionaries in the story are given names: Sister Hannah— a name derived from Red Cloud and her youth, a name that would have delighted her siblings—and Norman Girrard, described as the “pale eyed theological student” torn between serving art and the church. Like the early, tolerant Jesuit missionaries, Girrard (his name suggesting French ancestry) befriends Cantonese importer Sum Chin without trying to change him. Sketching Sum Chin in the backroom of his shop, Girrard draws inspiration from this exotic space (324). Initially, these “séances” are mutually helpful: Sum’s stories and surroundings excite Girrard’s imagination, and Girrard arranges through “the Rescue Society” the immigration of Sum’s Chinese bride, circumventing the Chinese Exclusion Act. Eventually Girrard accepts a large bankers’ check for services rendered on behalf of Sum’s infant son, but does not pressure Sum to convert to Christianity. Sister Hannah’s ministrations, by contrast, are calculated and pecuniary; she covets Sum Chin’s influence among his people and the souls of his wife and child. In her eyes, the merchant equates to a literal sum: “a convert worth a hundred of the coolie people” (323). Hannah labors to convince the rich man’s wife, Sum Loo, of the value of Christianity, for “above all things [Hannah] desired to have the [infant Sum Wing] baptized” (328).

The title of the story promises the conversion of a pagan Chinese family to Christianity in the manner of Sunday-school fiction. But the rug is pulled out as the healthy toddler is killed by holy water, the premature “joy at the Mission of the Heavenly Rest . . . [is] turned to weeping,” and the grieving parents reject Christianity (329). Abandoned by his domestic gods and mocked by the priest of the Joss House (Taoist temple) across the street, Sum Chin changes from a model husband to a “broken old man” who shuns his friends and demands that his wife “cleanse herself from the impurities of the Foreign Devils” (330), a clear allusion to the Boxers’ cry to “extirpate the foreigner.” Without a son to pray for the repose of his ancestors, Sum Chin expects eternal torment.[9] His wife is changed from a joyous mother to a depressed penitent, spending her days atoning for childlessness in the Taoist temple.

Not just the Chinese couple but also the erstwhile missionaries are transformed by the catastrophe. Girrard quits church and country to “become an absinthe drinking, lady-killing, and needlessly profane painter of oriental subjects and marines on the other side of the water” (324). And in the story’s last paragraph, even stolid Sister Hannah is touched after pursuing Sum Loo into the Joss House, having been barred from the Sums’ home. Within the temple, Hannah beholds Sum Loo kneeling before the altar of the goddess of childbirth, burning tapers made from folded pages of the Chinese New Testament. Hannah retreats in terror, all her verities gone up in smoke, and that night withdraws her application to the Board of Foreign Missions (331).

The fictional Sister Hannah had but to cross the street to disrupt the Sum fortunes, but an actual Episcopal deaconess named Sister Hannah, known to the Cather siblings, literally held together the Grace Church of Red Cloud (Bennett,“Cather and Religion”). Bennett explains that as the Baptist congregation declined in numbers, the Cathers began attending Grace Church in the 1880s and joined in the 1920s, by which time Grace had become the town’s “elegant church” (11). But throughout Cather’s childhood, Grace had been a struggling mission, ill-served by a succession of itinerant priests who rode a hundred-mile circuit preaching to congregations in fourteen other towns. Surveying the church’s many incarnations in Cather’s fiction, Brent Bohlke recalls that Grace suffered “false starts, . . . disappointments, and much travail” until Sister Hannah arrived and took “charge . . . as the licensed lay reader” (6). Finding the church building badly twisted by a tornado, the tireless Sister had its frame “brace[d] . . . with iron rods,” had the structure moved to a more central lot in town, and had its shattered plaster walls replaced. She held fundraisers to pay for the renovations and doubled the church’s membership before she departed Red Cloud in March 1893 (Bennett, “Cather and Religion” 11; Bohlke,“Grace Church, Red Cloud” 7).

While few outside of Red Cloud would have appreciated her satire on the real Sister Hannah, Cather took a greater risk in making her fictional deaconess flee from the sight of fire, for the near-martyrdom of Charlotte Hawes and her companions was fresh in the collective memory of Pittsburghers. The public learned on 7 July that the fugitives from Wei Hsien had reached safety, but the days between the arson and the first telegram from Frank Chalfant must have been agony for family, friends, and congregational sponsors. Nellie Nevin told The Library she was “besieged with questions” regarding Charlotte’s safety, perhaps unconscious of comparing her own ordeal to the ongoing siege of the legations.[10] On 24 July, almost a month after the event, the first accounts of the Pittsburgh missionaries’ flight from the Boxers appeared in the city newspapers.

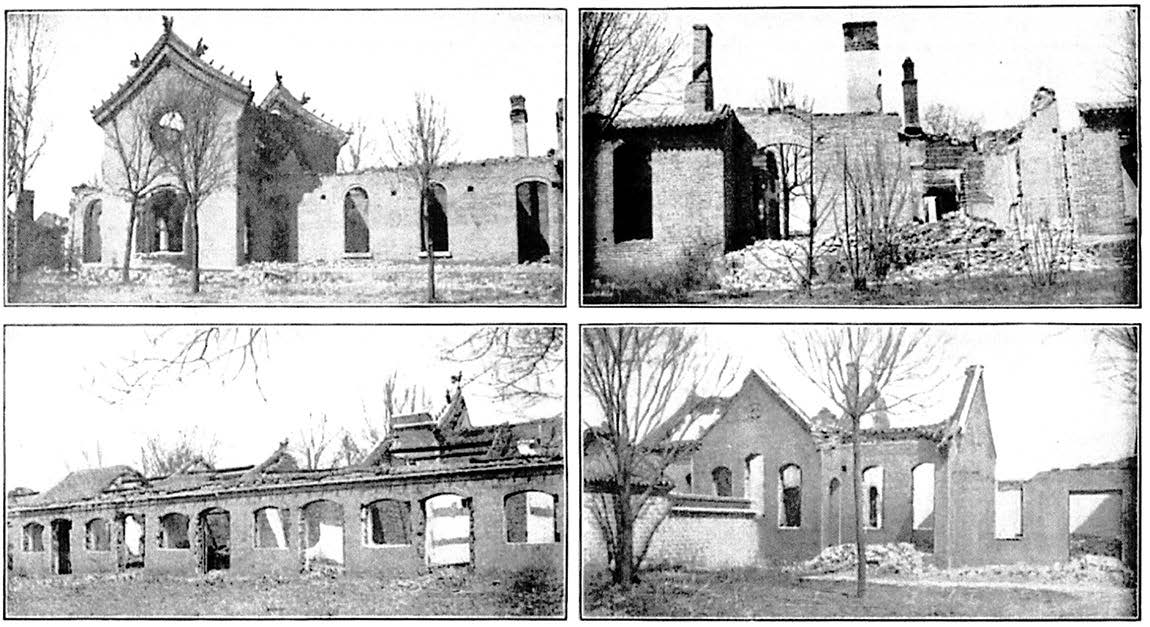

Frank Chalfant explained that when he learned of the Allies firing on the Taku

forts, he and the other minister at Wei Hsien, C. S. Fitch, anticipated trouble.

It was decided that Reverend Fitch should escort the fourteen American women and

children to a steamer waiting at the coastal city of Chefoo, about two hundred

miles distant. The Fitch party left on 23 June, while Frank Chalfant would remain

until the two women who were teaching Bible classes in the off stations—Miss

Emma Boughton and Miss Charlotte Hawes—could be warned and recalled. Miss

Boughton was not far afield, but Miss Hawes had to travel fifty miles nonstop by

mule litter so did not reach Wei Hsien until the early morning of 25 June. The

three missionaries crated their belongings and reserved carts to depart early the

next morning, but by 5:00 p.m., hundreds of rioters had gathered outside the

mission walls. Armed with a revolver, Frank Chalfant mounted the wall and ordered

the crowd to disperse, but his commands were answered with jeers and a hail of

bricks. In a later interview, Charlotte Hawes described what transpired: [Reverend Chalfant] said he would shoot [only if] absolutely

necessary, and he did fire over their heads several times. These shots were met

with the cry, “Big Knife society don’t fear guns.” He finally came in [to his

residence] after killing one Boxer and injuring several more, and told us that

the crowd was getting stronger and an attack was imminent . . . The Boxers in

the meantime had come in at the south gate . . . We did not know exactly what

was to be the method employed in our death until suddenly a little [child]

cried out, “See, they are picking up firewood.” We pulled open the curtains on

the east of the house and saw that the chapel was on fire and on the other side

my house could be seen in flames. We supposed that the flames would soon be

applied to the building we were in and that we would be burned to death.

(“Escaped the Boxers,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 14

August 1900, p. 3)

Fig. 3.4. The ruins of Wei Hsien mission, rebuilt the following year. From

The Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of

Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church of the United States, May 1901,

p. 102, Google Books. As the mob broke into the rear of the residence and paused to examine

the crated belongings piled in the study, the Americans realized the front yard

was deserted. Separated from the Boxers by only a sliding door, they stole out of

the residence and used a ladder to cross the twelve-foot wall. While helping one

of the female servants to clamber over, Frank Chalfant dropped his revolver;

thereafter, their only defense was a hammer that Miss Hawes had carried away from

her packing. Crossing fields to avoid villages and roads, the fugitives reached

the German coal mines at Fangtze, about ten miles away, around midnight. There

they were taken in by the German mining engineers who afterward provided a

military escort to the coast.[11]

Fig. 3.4. The ruins of Wei Hsien mission, rebuilt the following year. From

The Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of

Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church of the United States, May 1901,

p. 102, Google Books. As the mob broke into the rear of the residence and paused to examine

the crated belongings piled in the study, the Americans realized the front yard

was deserted. Separated from the Boxers by only a sliding door, they stole out of

the residence and used a ladder to cross the twelve-foot wall. While helping one

of the female servants to clamber over, Frank Chalfant dropped his revolver;

thereafter, their only defense was a hammer that Miss Hawes had carried away from

her packing. Crossing fields to avoid villages and roads, the fugitives reached

the German coal mines at Fangtze, about ten miles away, around midnight. There

they were taken in by the German mining engineers who afterward provided a

military escort to the coast.[11]

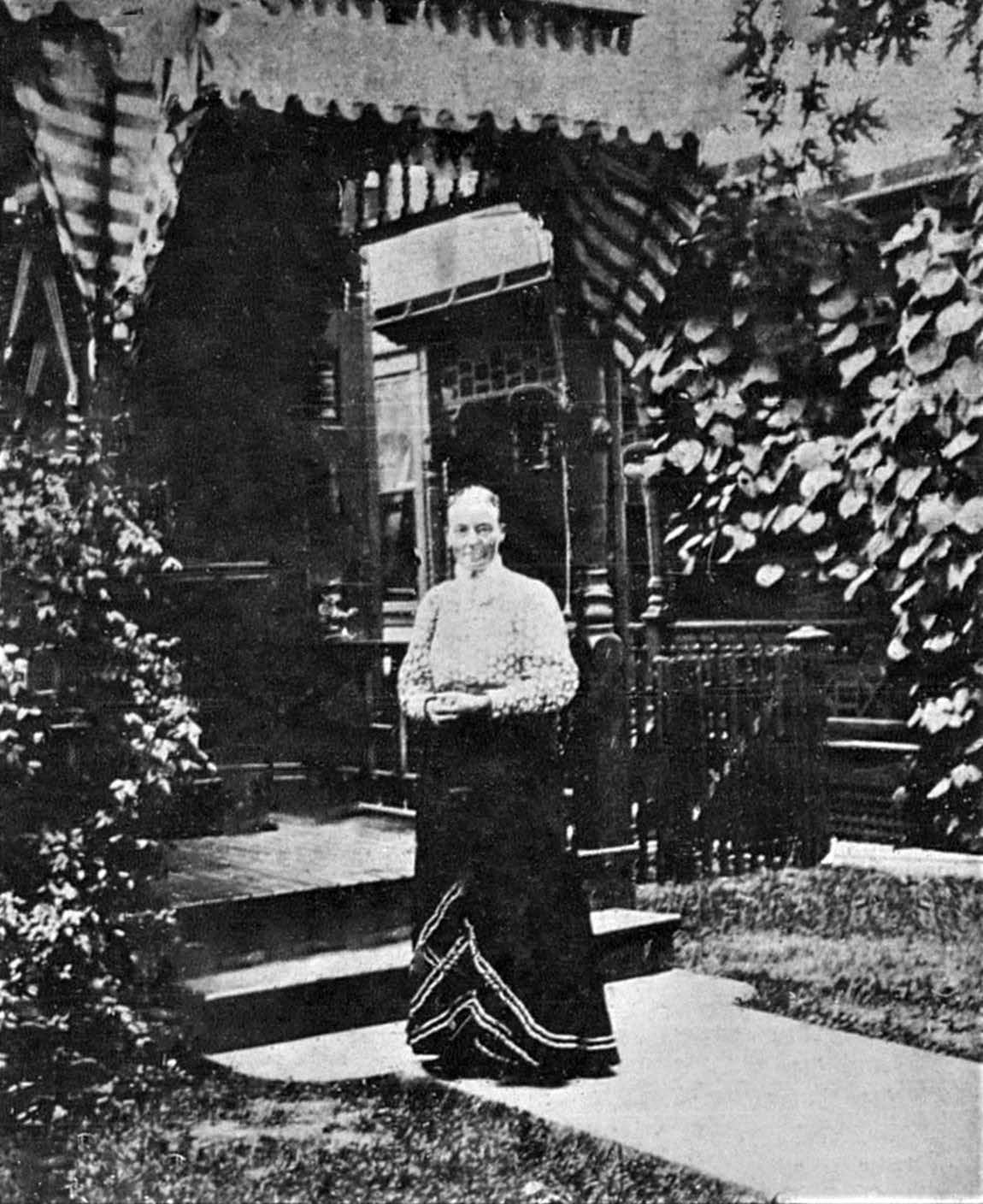

Fig. 3.5. The Library published “the first photograph of

[Miss Hawes] since her return from China, taken . . . on the day after her

arrival in Pittsburgh,” 18 August 1900, p. 3.

Fig. 3.5. The Library published “the first photograph of

[Miss Hawes] since her return from China, taken . . . on the day after her

arrival in Pittsburgh,” 18 August 1900, p. 3.

News of the attack reached Pittsburgh via cable on 26 June. Reverend Fitch’s party was known to have reached Chefoo safely, but nothing had been heard from Frank Chalfant, Emma Boughton, and Charlotte Hawes as rumors flew that all of the missionaries in the province had been killed. Finally, on 7 July, a cablegram from Frank Chalfant reached the Board of Foreign Missions in New York, who forwarded his message to his minister father in Pittsburgh. In the next day’s newspapers, Dr. George Chalfant confirmed that the three were safe (“Chalfants Are Believed Safe,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 6 July 1900, p. 8).[12] Two days after the publication of “The Conversion of Sum Loo” in The Library, Charlotte Hawes arrived in Pittsburgh on the steamer Empress of Japan, escorting eleven-year-old Margaret Chalfant, one of Reverend Fitch’s evacuees (“Escaped the Boxers,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 14 August 1900, p. 3).[13] That day, Charlotte granted the city press several interviews. One titled “The Home-coming of Miss Hawes” appeared in the 18 August issue of The Library (see figure 3.5).[14]

By making Sister Hannah withdraw her application to the Board of Foreign Missions, Cather seems to have anticipated Nellie Nevin’s reaction to her sister’s peril. Charlotte told The Library that she intended to return to China “as soon as it was advisable” (“The Home-coming of Miss Hawes”), but the 1901 annual report to the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions confirms that “on account of need in her home” Miss Hawes had resigned (102). It appears Charlotte took a furlough at the insistence of her sister who had been so proud of her service earlier that summer.

If, when Cather left Red Cloud for Pittsburgh, she assumed she had escaped small-town showboating, she may have resented Nellie Nevin colonizing with her sister’s letters the magazine Cather made her own. Two decades later, a small scene in One of Ours appears to reference Nellie Nevin indirectly. After a shopping date in Hastings, Enid asks Claude to accompany her on a social visit to Brother Weldon. Seated in Mrs. Gleason’s parlor, Weldon reads Carrie Royce’s letters from China aloud,“without being asked to do so,” to Enid’s great delight and Claude’s intense disgust (180). Enid seeks Weldon’s counsel about whether she ought to follow her sister to China, but like Nellie Nevin or the fictional Sister Hannah, Weldon equivocates. Claude observes that Weldon is “careful not to commit himself, not to advise anything unconditionally, except prayer” (181). Instead of encouraging Enid’s missionary ambitions, Weldon urges her to do her duty on the home front and “reclaim” Claude through marriage, for, Weldon says, “the most important service devout girls could perform for the church was to bring promising young men to its support” (242). The adjective “devout” links Enid to the “devout deaconess” Sister Hannah, who Cather wrote,“should have had her own children to bother about” (“Conversion of Sum Loo” 328)—which sentiment a younger Cather may have applied to Miss Hawes and her Chinese lambs.

In the same issue of The Library that contained “The Conversion of Sum Loo” (11 August), Ewan Macpherson addressed the latest wrinkle in the debate over who was to blame for the Boxer trouble. The week before, the Reverend Regis Canevin, rector of Saint Paul’s Roman Catholic Cathedral in Pittsburgh’s East End, offended many Presbyterians when he told a newsman that Protestant missionaries in China should not demand invading armies rescue them but should instead, like their Catholic brethren, be prepared to die as martyrs. “I am not opposed to the deliverance of legations and Europeans whose lives are imperiled by the attacks of the Chinese,” Bishop Canevin clarified the next day, “but I am opposed to the sending of a single regiment to protect or assist the missionaries who are engaged in preaching the Gospel of peace” (“Rev. Canevin on China,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 4 August 1900, p. 4). Making converts at rifle point, Canevin insisted, was incompatible with Christian principles; further, he suspected that the European powers were using the missionary crisis as an excuse to further their imperialist agenda: There are missionaries and missionaries . . . The first cabled message has yet to come from one of my faith asking for soldiers. They will die as they have lived, without a murmur, without the shriek for protection. The press teems with the plaints of . . . the Protestant workers grouped here and there in the disturbed districts . . . I am opposed to the [Allied military] advance on China . . . Better . . . the death of every missionary . . . than the landing of thousands of soldiers and the infliction of all the horrors and evils of war on [China’s] shores. (“Rev. Canevin on China,” p. 4) Canevin denied that Catholic missionaries were any more resolute than their Protestant counterparts, but pointed out that most of his faith were unmarried, whereas Protestant missionaries were commonly accompanied by their wives and children. If Protestant ministers were willing to die for Christ, they were less willing to sacrifice their loved ones. As a member of the Catholic minority in Pittsburgh, Ewan Macpherson seemed embarrassed by the so-called Canevin controversy; his column in The Library urged Christians of all persuasions to close ranks, asking, “Would it not be to [the clergy’s] general advantage to show a solid front not only against Prince Tuan and the Boxers, but also to the thousands of angry critics among Christian nations who recent events have stirred up against them?” (“For Our Country’s Good,” 11 August 1900, p. 14).

Cather seems to have been one of those angry critics who believed the Chinese should be allowed to work out their own salvation. As “Lee” Chin maintained in “A Chinese View,” she thought “the Chinese were very well satisfied with their own religion and they think their Empire a dear price to pay for a new one” (17). Two decades later, Cather alluded to the Bishop Canevin controversy when Enid asks Brother Weldon if her own chilly personality may have been ordained by Providence to hold her “in reserve for the foreign field—by not making personal ties” (One of Ours 181). Although married and an evangelical Protestant, Enid prefers to live as a chaste bride of Christ, like a Catholic sister. Claude remarks on her willingness to separate, “It’s not only your going . . . It’s because you want to go. You are glad of the chance to get away among all those preachers, with their smooth talk and make-believe” (297).

Claude conceded that “when [Enid] made up her mind, there was no turning her” (294), and Charlotte Hawes proved just as indomitable. By 1903, Miss Hawes was back at Wei Hsien, where she remained for more than twenty years, except for an occasional furlough, through revolutions, outbreaks of pneumonic plague, and terror campaigns against Christian missionaries (“Pittsburg Missionary is in the Danger Zone”). Defying contagious disease and violence, she lived to be eighty-five, dying in Pittsburgh on 25 November 1944 (“Miss Charlotte Hawes,” Pittsburgh Press, 26 November 1944, p. 36).

Whether Miss Hawes’s many Pittsburgh friends took offense at “The Conversion of Sum Loo” is difficult to determine. I have located no outraged letters in the city press. The story was Cather’s last word in The Library and may have signaled her temporary leave-taking from the city. The Library failed in September (as anticipated by Seibel and Cather), about the time she left Pittsburgh to assist her cousin Howard Gore in Washington dc (Seibel,“Miss Willa Cather,” World and the Parish 2: 755). If the story did give offense, the damage was not lasting, for beginning in January she published a Washington letter in The Index of Pittsburg Life, which had absorbed some of The Library’s staff (World and the Parish 2: 793).

Though Cather’s association with The Library lasted just six months, we should not discount its importance. The spring and summer of 1900 that proved so calamitous for the Chinese was for her a time of intense productivity and high spirits. She wrote to Will Owen Jones at the end of September that the year had been “the happiest of her life so far” (Woodress 147). And although The Library was no more, in later years her friendship with Ewan Macpherson resumed. Edith Lewis remembered Macpherson as “a fine scholar, with a thorough knowledge of Catholic tradition,” who had intended to become a priest, but abandoned this vocation to marry (147). From 1905 to 1912, Macpherson worked for the Catholic Encyclopedia in New York, where he and Cather met for conversation. Lewis credits these “long talks,” in part, for giving Cather confidence to attempt another missionary story, Death Comes for the Archbishop (148), which, like One of Ours, may have long tendrils stretching back to Pittsburgh.[15]