From Cather Studies Volume 13

Venetian Window Pittsburgh Glass and Modernist Community in “Double Birthday”

“Double Birthday” (1929) is Willa Cather’s glass story. Its centerpiece is “a large stained-glass window representing a scene on the Grand Canal in Venice” (“Double Birthday” 48), installed in the spectacular late-nineteenth-century Allegheny City, present-day North Side, home of the Engelhardts, a once affluent family of Pittsburgh glass manufacturers who have since fallen into ruin and obscurity. Their last survivors by the late 1920s are one son (of the original five) and an uncle, aged fifty-five and eighty, respectively, both named Albert, both bachelors, sharing the same birthday and, at this point, the same upper floor of a house they split with a glassworker’s family on Pittsburgh’s South Side, the Engelhardts’ last surviving property. Once neglected by critics, “Double Birthday” has in recent years attracted notice for its dialectical representation of space and time. I have studied how Cather “integrates four sections of Pittsburgh—South Side, Squirrel Hill, Allegheny, and downtown—conventionally separated by forces of class and history” (Murphy, “Dialectics” 255–56). Joshua Doležal identifies “a remarkable synergism of past and future,” “a coupling of worlds in time” that is Cather’s answer to political progressivism (414, 425). In their biographical study, Timothy Bintrim and Kari Ronning ground the story’s spatiotemporal coordinates in the tragic but industrious life of Cather’s Allegheny friend and mentor George Gerwig. Most recently, David Porter discusses “Double Birthday” as a “pivot” text between the largely comic energies of The Song of the Lark (1915) and the tragic mood of Lucy Gayheart (1935). Here I will reconsider the story’s dialectical structure through its most distinctive architectural feature: its central Venetian window, which serves as an entryway to Cather’s depiction of modernist consciousness and community.

In their Allegheny City heyday, the Engelhardts of “Double Birthday” were known by their stained-glass window. The progress of the story’s tragic heroine, the budding vocal artist Marguerite Thiesinger, from Pittsburgh to a burgeoning career in New York under Uncle Albert’s sponsorship, originates from her instinctive desire “to see that beautiful window from the inside” (49). But the reader is not privy to Marguerite’s inside view of the window. That view remains a hidden source of illumination—one of the story’s many lacunae—an index to an entire world obliterated, emotionally if not physically, by the Great War, the fault line dividing the narrative’s present and past. To reconstruct an insider’s knowledge of this window, I am seeking here to understand its aesthetic form, its Venetian subject, and ultimately its emotional register for the Engelhardts and the surrounding community at a time when Pittsburgh was the leading glass-manufacturing city in the United States.[1] I am also trying to account for the Venetian window’s elusive presence—why the experience of it, so familiar to the characters, is largely withheld from the reader. As such, I will read deeply and broadly into a relatively succinct architectural detail, albeit one exhibiting a characteristically Catherian expansiveness that permeates the narrative and opens into history. My study will involve the battle of styles in late nineteenth-century American stained glass—especially the phenomenon of opalescent glass—and the contemporaneous iconology of Venice, as well as the modernist technique Cather pursues in this mature, uncollected story of the late 1920s. Throughout, I will consider the Venetian window as a work of art that constructs a particular relationship with its audience (both within and outside the narrative) through its social and historical significance, its visual dynamics, and its Venetian imagery.

THE INNER SANCTUM

In “Double Birthday,” the Venetian window is a teasing sign of both openness and exclusivity. It is the public face of the Engelhardts, a prominent German family in a neighborhood then known as Deutschtown, facing west toward Allegheny market: “Everyone knew the Engelhardt house, built of many-colored bricks, with gables and turrets, and on the west a large stained-glass window representing a scene on the Grand Canal in Venice, the Church of Santa Maria della Salute in the background, in the foreground a gondola with a slender gondolier” (48). As public image, the stained glass duly represents August Engelhardt as a glass magnate in the nation’s glassmaking capital, while at the same time distinguishing, through fine artisanal work, his family’s domestic retreat as a separate sphere from their “flourishing glass factory up the river” (42). The window is the most distinctive feature of a house—“big, many-gabled, so-German” (45)—that pegs the family as affluent but also singular and ethnic, with “that queer German streak in them” (42). In its touristic associations, the window seems to foretell the Engelhardt sons’ drift from their father’s business toward “fantastic individual enterprises” (42). Images of the Allegheny household dwell on its external, theatrical signs of leisure, calling to mind “people in a book or a play”: “flowers and bird cages and striped awnings, boys lying about in tennis clothes, making mint juleps before lunch, having coffee under the sycamore trees after dinner” (57); “flowering shrubs and greenhouses . . . so well known in Allegheny” (53).

While the Engelhardts play out their lives as a kind of theater under the sign of the Venetian window, the window, in its impermeability, also establishes the limits of their public intercourse. More than a medium for light, the window is a façade. Cather’s matter-of-fact description emphasizes its scenic elements—canal, church, gondola, gondolier—rather than its translucence as stained glass. The eyes of the public fasten on the window, yearning for the personal touch, openly visible, that will glimpse the underlying domestic intimacy of “a public-spirited citizen and a generous employer of labor” (43). When that intimacy is not forthcoming, the people imagine it for themselves: “People said August and Mrs. Engelhardt should be solidly seated in the prow [of the gondola] to make the picture complete,” a public daydream that persists even after August Engelhardt’s death (48). The empty space in the gondola creates for the reader a sense of aesthetic incompleteness, a phantom presence generating an atmosphere of suspense and possibility.

The Venetian window’s impermeability and incompletion heighten the drama of gaining access. Everyone knows the house with the Venetian window, but only inductees like Marguerite Thiesinger and Margaret (“Marjorie”) Hammersley, linked by their given names, are chosen to enter its inner sanctum. For Marguerite, her voice is her passport. Uncle Albert has the opportunity to distinguish her “one Voice” among a larger chorus because “the chapel windows were open” as he passes Allegheny High School on his customary morning walk. Following that voice to its source in the chapel, he encounters Marguerite singing, solo now, Carl Bohm’s “Still Wie die Nacht,” and invites her to have lunch and sing in the Engelhardt home. Marguerite’s reply—“Oh, yes! . . . [S]he’d always wanted to see that beautiful window from the inside”—sketches the terms of a covenant still under negotiation: Uncle Albert, having apprehended her voice through the open chapel windows, will cultivate that voice behind the Venetian window, the private sanctum of the Engelhardt home replacing the public sanctuary of the school chapel. In exchange, Marguerite gains access to a German clan who outclass her own “very ordinary” German people, and to the inner view of the Venetian window, which becomes invested with her voice’s potential (48–49). By contrast, as a social peer, young Marjorie Hammersley’s access to the Engelhardt house requires no display of artistic talent, only a desire to escape the mating rituals of “the young men in her set,” who “grabbed [a girl] rather brutally,” and to enjoy a family who appreciates her “aesthetically” (57). For both Marguerite and Marjorie, however, the Venetian window marks an exclusive passageway into an aesthetic realm that suspends the city’s materialistic ambitions. As Uncle Albert counsels Marguerite, “There is something vulgar about ambition. Now we will play for higher stakes; for ambition read aspiration!” (51).

From the story’s 1920s present, the memory of the Allegheny house with its signature window becomes a metonym for the irrecoverable world “before-the-war” (60). So it is for the adult Marjorie Hammersley (now the widow Mrs. Parmenter) who recalls the house as a “wonderful” place of “music” and a thing to “cherish” (61). Back in the day, it impressed Marguerite as “magnificent” (49). The Alberts, in their household ways and wares, have re-created something of the Allegheny house’s luster in their “workingman’s house” on the South Side (45), which Marjorie calls “the only spot I know in the world that is before-the-war. . . . You’ve got a period shut up in here,” she tells them, “the last ten years of one century, and the first ten of another” (60–61). Nephew and uncle, in dignified poverty, tend the embers of an all-but-vanished age. However, the reader never experiences what would be the visual apotheosis of this one-time magnificence: the stained-glass image of Venice on the west side of the Allegheny house as Marguerite long desired it, privately viewed from within, backlit by the afternoon sun. This spectacle, so carefully intimated, never appears in the story. The principal characters share luminous experiences of the window to which the reader has no access.

OPALESCENCE

It would seem arbitrary to make an issue of what Cather doesn’t describe, were the alternative not so plausible. Cather understood the phantasmagoric potential of glass. When Black Hawk is frozen over in My Ántonia (1918), narrator Jim Burden feels the unconscious pull exerted by the Methodist Church window: “I can remember how glad I was when there happened to be a light in the church, and the painted glass window shone out at us as we came along the frozen street. . . . Without knowing why, we used to linger on the sidewalk outside the church . . . shivering and talking until our feet were like lumps of ice. The crude reds and greens and blues of that colored glass held us there” (168–69). In One of Ours (1922), Claude Wheeler spends an hour in Rouen’s church of St. Ouen contemplating “[t]he purple and crimson and peacock-green” light of the rose window that “[h]e felt distinctly . . . went through him” (452). Or consider, in Shadows on the Rock (1931), the light show performed for Cécile by Count Frontenac’s “crystal bowl full of glowing fruits of coloured glass: purple figs, yellow-green grapes with gold vine-leaves, apricots, nectarines, and a dark citron stuck up endwise among the grapes. The fruits were hollow, and the light played in them, throwing coloured reflections into the mirror and upon the wall above” (71). Clearly Cather was not blind to the power of glass as a subject for word painting.

The preeminent example of the era, in a work she admired, is Henry Adams’s meditation on the twelfth-century glass of Chartres Cathedral in Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (1904).[2] “[N]o opaque color laid on with a brush, can compare with translucent glass,” writes Adams, transfixed by “the limpidity of the blues; the depth of the red; the intensity of the green; the complicated harmonies; the sparkle and splendor of the light” (124, 132). On her own visit to Rouen in 1902, Cather marveled at “the burning blue and crimson of two rose windows” in the cathedral “almost as beautiful as those of Notre Dame” (World and the Parish 2: 923). For Cather, the luminosity of stained glass served as a handy metaphor. She once thanked her publishers, the Knopfs, for an especially fine case of Rothschild wine from the South of France, which she praised in terms of glass and light: “It is a superb wine, and shall be reserved for special occasions when I feel a little hard and want to have a glow put into things, a kind of stained glass treatment of pallid daylight” (Selected Letters 331).

Fig. 11.1. Opalescent window, 820 Cedar Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Probably Rudy Brothers Studio, 1894 or after. Photograph by Joseph C.

Murphy.

Fig. 11.1. Opalescent window, 820 Cedar Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Probably Rudy Brothers Studio, 1894 or after. Photograph by Joseph C.

Murphy.

Why, then, the inertness of Cather’s Venetian window, her neglect of its translucence and her decision not to capitalize on its spectacular potential as glass? I’ll pursue these questions on two levels, first in regard to the type of stained glass Cather had in mind, and second in regard to her modernist goals in “Double Birthday.” In other words, what would the Venetian window have looked like, and why does Cather’s representation of it matter for an interpretation of her modernism?

Historical models for the Venetian window are elusive but not beyond reach. The search begins with the prototype of the Engelhardt house at 906 (formerly 66) Cedar Avenue on Pittsburgh’s North Side, formerly the residence of Cather’s Lincoln friend George Gerwig—a historical context already richly detailed by Peter M. Sullivan as well as Bintrim and Ronning. This gabled and turreted house, probably dating from the 1870s, contains no window depicting a Venetian scene, though it does feature a handsome iris-motif window on the second floor west façade. Neighboring houses at 902 and 820 Cedar contain turn-of-the-century stained glass, facing Suismon Avenue, depicting scenes that, though not specifically Venetian, do feature boat-and-water motifs with vaguely Italianate scenery: peninsulas, poplars, turrets, a loggia with Romanesque arches. In the 820 Cedar window, a solo boatman, his image doubled in the water, is a stout forerunner of Cather’s “slender gondolier” (figure 11.1). These two scenic windows, which Cather would certainly have noticed while visiting the Gerwig house and commuting to her job at nearby Allegheny High School (Bintrim and Ronning 83), may be the closest we come to locating prototypes for her fictional Venetian window. Both these windows are examples of the opalescent style popularized by John La Farge and his rival Louis Comfort Tiffany beginning in the 1880s, characterized by glass “in multicoloured, marbleized sheets, often with an iridescent sheen” (Raguin 224).[3] Throughout the United States, opalescent windows became the upper-middle-class fashion for homes as well as religious and educational buildings. American glass studios adopted opalescent glass as their primary medium, defining the period between 1880 and 1920 as the “opalescent era” and making “American Glass” synonymous with opalescent glass (Raguin 224,230; Tannler,“Classical Perspective”). Veteran Pittsburgh glass restorer John Kelly identifies the Cedar Avenue scenic windows as, without question, the work of the Rudy Brothers, who operated one of the major opalescent glass workshops in Pittsburgh at the century’s turn.[4] The brothers Frank, J. Horace, Jesse, and Isaiah Rudy opened their first shop in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty section in 1894. An early patron was industrialist H. J. Heinz, who commissioned stained-glass windows for his Point Breeze neighborhood residence and his factory (“Guide”). A list of the Rudy company’s clientele “reads like a litany of the new managerial and middle class: broker, pay master, physician, lawyer, superintendent, dentist, doctor, and so on” (Madarasz 101–2).

As a status symbol, opalescent glass would have been the obvious choice for an industrialist like August Engelhardt; moreover, its nature is consistent with Cather’s muted rendering of her Venetian window. Modernizing the antique “pot metal” technique—in which glass pieces colored by metal oxides were stitched together by prominent leadwork (Gossman et al. 40)—opalescent windows subordinated the leadwork to a pictorial design showcasing milky streaks and whorls of color. Opal or milk glass, which had long been used in tableware, is formed by incorporating a compound of “peroxide of tin or stannic acid, antimonic acid, chloride of silver, phosphate of lime, or bone ashes” into the glass (La Farge 1). La Farge’s innovation was his use of opal glass for windows by combining it with ordinary colored glass in long sheets, stacking several plates on top of one another, and fastening them with lead (Raguin 231–32).

The opalescent style exhibits three hallmark properties. One is iridescence, that is, a slow-burning shimmer achieved by distributing light throughout the sheet rather than allowing it to pass through. Less translucent than medieval stained glass, and in some cases almost opaque, opalescent glass achieves its unique “movement and life when light illuminates it from behind” (Isenberg and Isenberg 4), giving piquancy to Marguerite Thiesinger’s desire to see the Venetian window “from the inside.” A second feature of opalescent glass is its subtle gradation of color, layered like paint but actually inherent in the glass itself. As such, opalescent glass diverges from the tradition of painted glass, dating from the Renaissance, in which paint was applied to the surface of clear glass (Gossman et al. 41–43). The third hallmark, extending from the second, is its formal imitation of perspectival painting. As La Farge explained in his 1879 patent application, opalescent glass enabled him, “by checking or graduating” the passage of light, “to gain effects as to depth, softness, and modulation of color” and achieve a higher degree of “realistic representation” (1). Cather’s description of the Venetian window calls attention to this illusionistic strategy—it is a window “representing a scene,” she writes—and deploys perspectival signposts to depict a cityscape formally at odds with the two—dimensionality of glass: “the Church of Santa Maria della Salute in the background, in the foreground a gondola.” Cather’s presentation of the Venetian window as painterly rather than translucent, then, captures an essential feature of opalescent glass.

Fig. 11.2. John La Farge, Fortune on Her Wheel, 1902,

Frick Building, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Albert Vitiello.

Fig. 11.2. John La Farge, Fortune on Her Wheel, 1902,

Frick Building, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Albert Vitiello.

Cather had many opportunities to experience opalescent windows throughout her career. In addition to the Allegheny neighborhood windows, she must have known La Farge’s monumental opalescent window Fortune on Her Wheel, installed in 1902 in the lobby of the Frick Building across from the Pittsburgh courthouse where Albert and Judge Hammersley meet in the opening scene of “Double Birthday” (figure 11.2). It depicts Fortune as a dramatic figure of turbulence, riding her wheel on choppy waters. Certainly, Cather admired the work of La Farge, who outfitted Manhattan’s Church of the Ascension, her “favourite church in New York” (Lewis 151), with four opalescent windows as well as the grand mural The Ascension of Our Lord (1887) above the altar. In an intriguing detail in a letter to her niece Margaret during a stay at Williams College, Massachusetts, in 1942, Cather describes herself “studying the stained glass in the chapel” (Selected Letters 612). The masterpiece of Williams’s Thompson Memorial Chapel is, in fact, an opalescent window by La Farge— his exquisite, layered rendering of Abraham and an Angel from 1882, dedicated to the memory of President James A. Garfield—suggesting the continuing allure of opalescent windows for Cather in later years.

The memorial function of stained glass was on Cather’s mind during mid-1928 when she was working on “Double Birthday,” as she was then considering options for a window in memory of her father in Red Cloud’s Grace Episcopal Church.[5] In this endeavor she was assisted by her Red Cloud friend Carrie Miner Sherwood, whom she wrote from New York on 13 June 1928: “I find stained glass a difficult thing to go shopping for, and I have decided to let Father’s window go over until next fall, when I hope I will have more energy.” By the following January she could write Carrie with more assurance, “I like the design you sent for Father’s window very much,” and, referring to another window Carrie was overseeing for the church, remarked: “I realize what a lot of work it takes to put anything of that kind through” (21 January 1929).

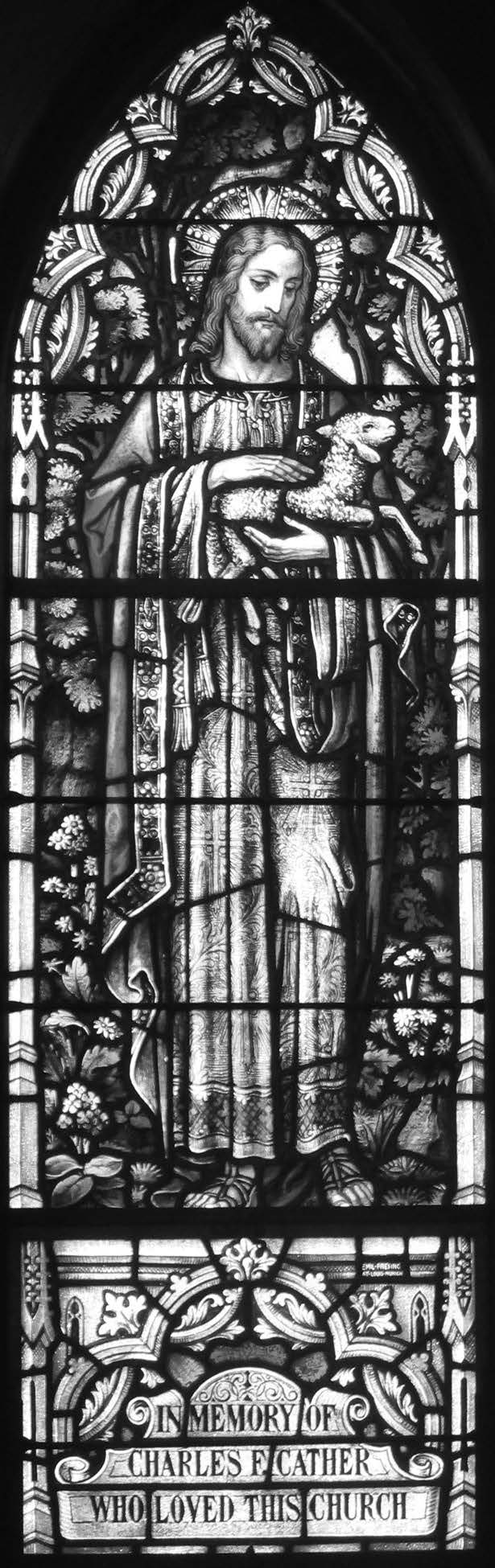

Fig. 11.3. The Good Shepherd, Emil Frei Company, St.

Louis and Munich, dedicated 5 December 1937. Cather memorial window, Grace

Episcopal Church, Red Cloud, Nebraska. Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy.

Fig. 11.3. The Good Shepherd, Emil Frei Company, St.

Louis and Munich, dedicated 5 December 1937. Cather memorial window, Grace

Episcopal Church, Red Cloud, Nebraska. Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy.

Cather’s sense of the difficulty of selecting a church window must have derived in part from her awareness of the array of contending styles available. The windows she ultimately chose to honor each of her parents are examples of the Munich style, manufactured by Emil Frei Company of St. Louis and Munich (figure 11.3).[6] Like the opalescent style, the Munich style, established in the early nineteenth century under the sponsorship of Ludwig I of Bavaria, represented a compromise between traditional medieval glass and post-Renaissance painted glass (Gossman et al. 44), but it clung much more closely to the latter tradition. While “made of traditional hand-blown antique glass,” Munich glass windows relied almost entirely on applied paint for an “idealized naturalism and spatial realism” that spread across the pane with less pronounced leading than medieval glass (Tannler, “Leo Thomas”). Painted glass maximizes the window’s pictorialism but minimizes its translucency, as far less light penetrates the enamel paint. Both the Munich and the opalescent styles were rejected by neo-Gothic boosters like Henry Adams, who believed that illusionistic perspective had no place in stained glass. “The twelfth-century glassworker would sooner have worn a landscape on his back than have costumed his church with it,” Adams protested. “He wanted to keep the colored window flat, like a rug hung on the wall” (126).

In any case, Cather opted to memorialize her parents in a style Adams trivialized as “opaque color laid on with a brush,” rather than in the neo-Gothic or opalescent styles (the latter being somewhat out of vogue by the 1920s [Raguin 235]). Her taste was evidently more eclectic than Adams’s. Finding aesthetic value in all these traditions, Cather was aware of a broad continuum between the translucent glass of the Middle Ages, at one extreme, and the “painted glass window” of My Ántonia’s Methodist Church, with its “crude reds and greens and blues,” on the other. Opalescent and Munich glass both fell along this continuum, but it was opalescent glass that more completely fused the medieval and Renaissance traditions, captivating the viewer with both its pictorialism and its intrinsic qualities as glass. It is this complex appeal of opalescence—the favored style for upper-middle-class homes before World War I—that an informed historical reading restores to the Engelhardts’ Venetian window.

GLASSWORK

The subdued quality of Cather’s Venetian window corresponds not only to the opalescent style but also, I will suggest, to the aesthetic and narrative sensibility she cultivates in “Double Birthday.” This sensibility is perhaps best summarized in Albert Engelhardt’s meditations (communicated through free indirect discourse) as he commutes home for his uncle’s birthday dinner and brushes aside any consideration of his own birthday: “If one stopped to think of that, there was a shiver waiting round the corner” (57). Crossing the Smithfield Street Bridge, surveying the flow of the Monongahela River beneath him and the heights of Mount Washington above, he truncates his thinking: “Better not reflect too much” (57). The line could serve as the motto for a story that implies reflection or mirroring in its title, “Double Birthday,” but here discourages reflection as a mental habit, even as it features a stained-glass window in which the reflective, refractive, and translucent properties of glass are restrained. Albert’s self-conscious chastening of reflection upholds Cather’s own modernist method, as described in “The Novel Démeublé” (1922), of creating “the emotional aura of the fact or the thing or the deed” “without . . . specifically nam[ing]” it (41–42).

Significantly, the story’s guarded attitude toward reflection— reflection in mind, reflection in glass—puts it at odds with the aesthetic tradition on which young Albert was weaned: the 1890s Decadent works of Aubrey Beardsley, Ernest Dowson, Oscar Wilde, even “a complete file of the Yellow Book,” which still line the shelves of his library but look, “though so recent, ...already immensely far away and diminished” (45–46). For the Decadents, who savored moods of loss and aftermath, the complex and diminishing play of light on reflective surfaces was irresistible. In Decadence and the Invention of Modernism, Vincent Sherry details the “familiarly decadent emphasis on reflected and secondary light” in a tradition extending from Henry

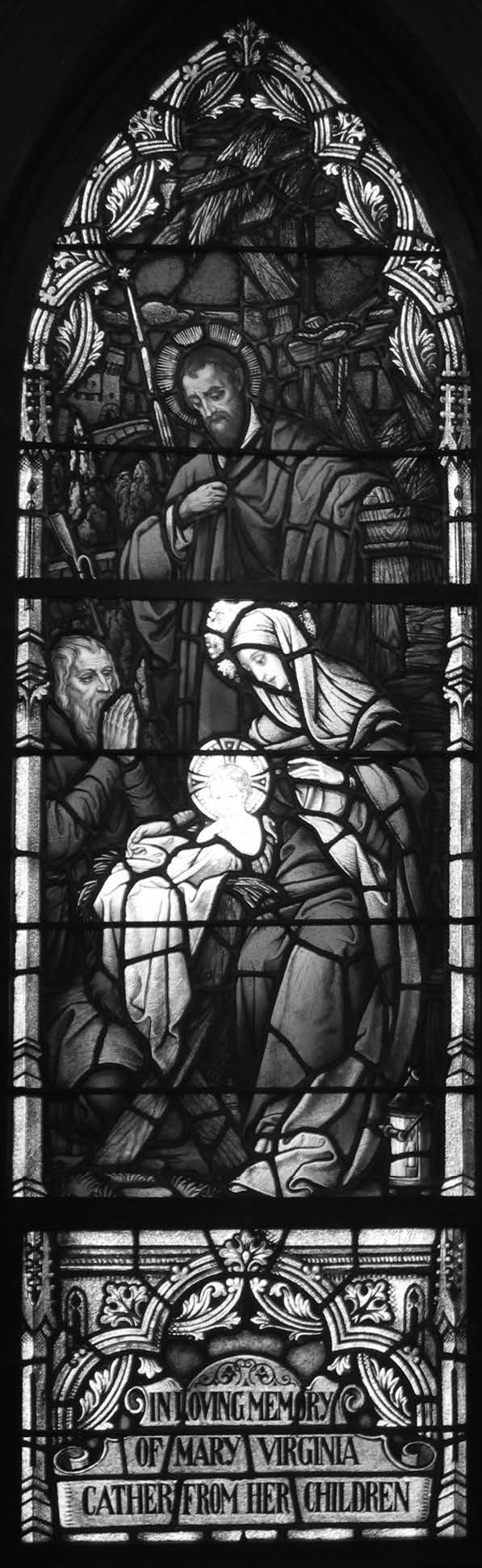

Fig. 11.4. The Holy Family, Emil Frei Company, St.

Louis and Munich, dedicated 5 December 1937. Cather memorial window, Grace

Episcopal Church, Red Cloud, Nebraska. Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy.

Fig. 11.4. The Holy Family, Emil Frei Company, St.

Louis and Munich, dedicated 5 December 1937. Cather memorial window, Grace

Episcopal Church, Red Cloud, Nebraska. Photograph by Joseph C. Murphy.

James to T. S. Eliot (273). Ellis Hanson, in Decadence and Catholicism, discusses stained glass as a Decadent figure for the aestheticized twilight of Christian belief, flickering and fading (10). Cather’s story at turns indulges and resists such aestheticized regret as it serves up scenes from the twilight of an American family. Uncle Albert prolongs a state of mourning for his “lost Lenore,” Marguerite (47, 62), her career cut short by a terminal illness, and even rekindles his faded Catholicism with occasional visits to “an old German graveyard and a monastery” (53). But the narrative foregrounds his more sanguine routines with Albert and with the Rudder family downstairs.

Cather’s alternative to the scattered light of the Decadents is iridescence, the peculiar property of opalescent glass, which holds light within itself by distributing it across the pane—making it appear “as if lighted by the sun” even on “a cloudy or dark day” (La Farge 2). The hidden iridescence of Cather’s Venetian window permeates and sustains the human relationships that develop around it. I have already suggested a bond between Marguerite Thiesinger and the Venetian window. Marguerite is the window’s secret sharer because she is herself a medium of light: “glowing with health,” “like a big peony just burst into bloom and full of sunshine—sunshine in her auburn hair, in her rather small hazel eyes,” “greenish yellow, with a glint of gold in them” (49, 50). Marguerite’s light is not scattered but focused in Uncle Albert. Even when, bitterly disappointed by her elopement, he burns her photographs—as if her light were contained in those effigies—she returns to him brighter than before. Nearing death, Marguerite resembles the stained glass that once captivated her, with “still a stain of color in her cheeks” (52). In her New York hospital room Uncle Albert mutters “Pourquoi, pourquoi?” at the window but receives no answer from “that brutal square of glass” (52), that is, an industrial window lacking any of the Venetian window’s iridescence. (As noted above, the story’s other variation on the term “brutal” describes the crass mating rituals of Marjorie’s social set, in contrast to the gentle refinement of the Engelhardt boys.) The answer comes only when Uncle Albert himself takes on the quality of opalescent glass, allowing Marguerite’s death-struggle to permeate his body, like light. “She never knew a death-struggle—she went to sleep,” he recalls. “That struggle took place in my body. Her dissolution occurred within me.” Through this struggle “something within [Uncle Albert] seemed to rise and travel” with the “puffy white clouds like the cherub-heads in Raphael’s pictures” (53). His absorption of Marguerite’s death recasts, in iridescent terms, an exemplum of the Virgin Birth popular among medieval commentators, that Christ passed into the world through Mary as light passes through a window: “[A]s light pierces glass without breaking it, so, too, God pierced Mary without breaking her” (Harris 303).[7] But if Marguerite’s “dissolution” within Uncle Albert does not break him, it certainly haunts him, like light suspended within an opalescent window. Her long twilight modulates inside him in his half-conscious moments before sleep, while listening to his nephew’s piano music: “[T]he look of wisdom and professional authority faded, and many changes went over his face, . . . moods of scorn and contempt, of rakish vanity, sentimental melancholy . . . and something remote and lonely” (46).

In sum, the opalescent style I am identifying in “Double Birthday”—in its signature window and an associated modernist sensibility—is distinct from the styles associated with both the medieval Gothic cathedral and its secular revival by the Decadent Movement. If the translucent stained glass of the Gothic cathedral elevated its medieval viewers toward the divine, the opalescent glass of the Venetian window only hints at transcendence. And if the Decadents savored secondary and reflected light, the opalescent style entails the preservation of light, analogous to the steady and protracted commitments that bind the urban community of Cather’s story. The narrative itself exhibits this same quality of iridescence, its illuminations restrained and muted.

PITTSBURGH'S VENICE

I must turn now from the window’s medium to its message, and briefly inquire: Why Venice? The window’s Venetian subject is by no means accidental; rather, it crystalizes a cluster of associations that resonate with the story’s plot, temporality, social vision, and position in Cather’s career.

Originally, for August Engelhardt the window would have advertised his cultural sophistication, enshrining an iconic view from the Grand Tour in the heart of bourgeois Deutschtown. European themes, notes Pittsburgh glassman John Kelly, “were heavily favored by the new American clientele who were able to afford a ‘commission’ for a landing window.”[8] Given Venice’s historical renown as a glassmaking center—Pittsburgh’s Old World predecessor—the Venetian theme suited old August’s industrial as well as cultural aspirations and extended directly from its medium. For the aspiring singer Marguerite, it is Venice’s rich historical association with vocal music that must underlie her attraction to the window. Nineteenth-century Pittsburgh as a whole had Venetian aspirations: its glassworks; its bridge-strewn, water-locked landscape; even H. H. Richardson’s romantic Bridge of Sighs linking the Allegheny County Courthouse (figure 11.5, the “gray stone Court House” where “Double Birthday” opens [41]) to its adjoining jail, refers to a Venetian original. For the next generation of Engelhardts the window would have accrued, with their dissipated status, associations of perpetual decline long attached to the sinking city of the Adriatic—a mood that suits Albert’s postwar reflection, crossing the Monongahela River, that “kingdoms and empires had fallen” (57). More personally, the window’s representation of Santa Maria della Salute (“Saint Mary of Health”), a Baroque church completed in 1681 to memorialize plague victims, captures in a single image both Marguerite’s “glowing . . . health” and her premature death.[9]

While living in Pittsburgh, Cather developed her own dualistic impressions of

Venice prior to her first visit there in 1908. She discovered an upbeat Venice

in Pittsburgh composer Ethelbert Nevin’s popular piano suite A Day in Venice, which she heard him perform in 1899 at his rural

Vineacre estate outside Pittsburgh, after his return from a year on the Grand

Canal. The program notes included in Cather’s essay “An Evening at Vineacre”

depict an amusement ride through a bracing and rejuvenating cityscape: “The

gondoliers are off for the day, out upon the historic waterways, gliding down

the Grand Canal, under the arched stone bridges, through deep, still streets

where the stone walls on either side are mossed with age, and the shadows make

the water green and the air is cool—and out again into the broad sunlit

lagoons” (World and the Parish 2: 631–32). Cather

describes in similar terms a Venetian scene by Spanish painter Martin Rico y

Ortega that she viewed at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art: “very blue

skies, a silvery canal, white and red houses, bridges and gay gondolas, and in

the foreground the dear Lombard poplars, the gayest and saddest of trees,

rustling green and silver in the sunlight” (World and the Parish 2: 762–63). In

her 1905 Pittsburgh story “Paul’s Case,” it is before such a “blue Rico” that

her art-struck protagonist Paul “lost himself” at the Carnegie (218).[10]

Fig. 11.5. Henry Hobson Richardson, Bridge of

Sighs, Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, Pittsburgh, 1888.

Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress

Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-DET-4A

10829. The “middle class,” Cather observes, prefer such idealized Venetian

scenes to “those of greater painters . . . who have darkened the canals of the

city with the shadows of her past” (World and the Parish

2: 845). She encountered this darker, brooding Venice in the pages of Gabriele

D’Annunzio’s roman à clef The Flame of Life (1900),

which she reviewed for the Lincoln Courier in 1901,

observing: “[T]he city with its dark and stirring past, the present decrepitude

and decay, are used to cleverly emphasize the picture of the aged and ailing

actress,” a character based on D’Annunzio’s estranged lover Eleonora Duse (World and the Parish 2: 861). Perusing “Double Birthday,”

one notes, beyond the window itself, an accumulation of conventional Venetian

touches, both light and dark: Marguerite’s soprano voice sounding in the

street, Elsa Rudder and her fiancé, Carl, dressed for masquerade, the city’s

suspect air, “not good for the throat” (48), and above all, the fate of the

suffering artist. By 1929, the motif of the suffering or dying artist in

Venice, exemplified in the career of Wagner and dramatized in the fiction of

D’Annunzio, Vernon Lee, and Thomas Mann, had hardened into a modernist

archetype.[11]

In “Paul’s Case” Cather specifies “the blue of Adriatic water” among the final

thoughts of Paul who, jumping into an oncoming train, catches an afterimage of

the “blue Rico” he had admired at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie (252).

Fig. 11.5. Henry Hobson Richardson, Bridge of

Sighs, Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, Pittsburgh, 1888.

Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress

Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-DET-4A

10829. The “middle class,” Cather observes, prefer such idealized Venetian

scenes to “those of greater painters . . . who have darkened the canals of the

city with the shadows of her past” (World and the Parish

2: 845). She encountered this darker, brooding Venice in the pages of Gabriele

D’Annunzio’s roman à clef The Flame of Life (1900),

which she reviewed for the Lincoln Courier in 1901,

observing: “[T]he city with its dark and stirring past, the present decrepitude

and decay, are used to cleverly emphasize the picture of the aged and ailing

actress,” a character based on D’Annunzio’s estranged lover Eleonora Duse (World and the Parish 2: 861). Perusing “Double Birthday,”

one notes, beyond the window itself, an accumulation of conventional Venetian

touches, both light and dark: Marguerite’s soprano voice sounding in the

street, Elsa Rudder and her fiancé, Carl, dressed for masquerade, the city’s

suspect air, “not good for the throat” (48), and above all, the fate of the

suffering artist. By 1929, the motif of the suffering or dying artist in

Venice, exemplified in the career of Wagner and dramatized in the fiction of

D’Annunzio, Vernon Lee, and Thomas Mann, had hardened into a modernist

archetype.[11]

In “Paul’s Case” Cather specifies “the blue of Adriatic water” among the final

thoughts of Paul who, jumping into an oncoming train, catches an afterimage of

the “blue Rico” he had admired at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie (252).

In Cather’s Venetian window, these multivalent tropes of Venice coalesce around the intriguing figure of the “slender gondolier.” We have seen that this gondolier engages the viewer’s imagination, inviting Deutschtown to envision Mr. and Mrs. Engelhardt “solidly seated in the prow to make the picture complete.” In relation to Marguerite’s death, the gondolier takes on the darker guise of Charon, the ferryman of Hades. For Albert, schooled in Decadent culture, the gondolier would have suggested more risqué associations. In the code of the English Decadents, for whom Venice was a bewitching destination (featured several times in Albert’s complete set of The Yellow Book), a “slender gondolier” carried a potentially erotic charge, by association with late-nineteenth-century male tourists seeking casual relations with the Venetian working class (Brady 207–17).[12] More broadly, it signaled the opportunity for the tourist to experience “a certain wholeness” through “intense forms of life in the here and now” (Booth 172)—an intensity of pleasure that Cather herself associates with gondoliers in her notes on Nevin’s A Day in Venice: “The gondolier laughs—at nothing—at everything, at life and youth, laughs because the sky is blue and the sun is warm, laughs for joy at the gladness and beauty of another day—a day in Venice” (World and the Parish 2: 631). As such, the lone gondolier adds a dash of frisson to the interclass communion among Engelhardts, Rudders, and Hammersleys on Pittsburgh’s South Side, but one wouldn’t want to push this analogy too far. The gondolier is not so much a figure to be interpreted, as a template for the stream of historical associations that play across the window’s surface. Despite its apparent inertia, the Venetian window is a vital register of the desires that have continually reanimated it, like the various moods that flicker across Uncle Albert’s face before sleep or the features of young Albert exhibiting “a kind of quick-silver mobility” (41). It is finally a medium not for light but for the history through which the story’s characters have persevered. One could say of the window, in its kaleidoscopic associations, what Cather says of Albert: that it “had lived to the full all the revolutions in art and music that [its] period covered” (55).

Among the revolutions the window registers are those of Cather’s own career: the plot and Venetian motif of “Double Birthday” quite explicitly recast, in a tragic mode, the materials of her 1915 novel The Song of the Lark.[13] The rise of Wagnerian diva Thea Kronborg, stewarded by her mentor Dr. Archie, culminates in the closing conceit of the nightly tides refreshing the Venetian lagoons, even as the “tidings” of youthful careers refresh the citizens of Moonstone, Colorado (Song of the Lark 539). “Double Birthday” reprises the device of a medical doctor shepherding a vibrant young singer’s career; however, Cather sacrifices Marguerite to a fate Thea is spared, while darkening the allusion to Venice. Here the picture of Venice, and the figure of storytelling, shifts from the irrepressible motion of tides through a “network of shining water-ways,” to the purposeful progress of a slender man through the Grand Canal, represented in glass. As such, storytelling devolves from a Wagnerian force of nature to something more fragile, though perhaps as powerful as Thea’s success in stoking a community’s “memories” and “dreams” (Song of the Lark 539).

In a particularly insightful account of Cather’s project, Richard Millington distinguishes between her “two modernisms”: an “authenticity” modernism, typified by The Professor’s House and classics by Fitzgerald and Hemingway, seeking “aestheticized” authenticities in an environment of “inauthentic values and degraded emotions infected by the economic” (3); and an “anthropological” or “readerly” modernism, evident in novels like My Ántonia and Shadows on the Rock, centered upon “acts of heightened or illuminated witnessing” within a particular cultural locale (11). According to Millington, Cather’s anthropological modernism, by abandoning the traditional developmental plot of the Victorian novel (which “authenticity” narratives like The Professor’s House also follow), “frees its readers, no less than its characters, from a customary repertoire of response, . . . from the depth-seeking, ending-hungry, explanation-driven trajectories of Victorian culture” (15). In “Double Birthday,” Cather charts a transition between these modernisms of authenticity and anthropology by depicting an unorthodox community of Pittsburghers forged in the afterglow of exhausted experiments and frustrated careers. On the one hand, both Alberts derive a “feeling of distinction” (48) from their nonconformist, artistic lives, and a sheen of authenticity from their aestheticized experiences of loss: Uncle Albert’s Gothic Romanticism (his “lost Lenore”) and Albert’s faded Decadence. On the other hand, these personal authenticities—lacking the aesthetic intensity of high modernism—quietly resolve into a domestic partnership sustained by an assortment of Pittsburgh friends. From the outset of “Double Birthday,” Cather signals that her anthropological interests will not follow a traditional developmental plot. “Even in American cities, which seem so much alike,” the story begins, “where people seem all to be living the same lives, striving for the same things, thinking the same thoughts, there are still individuals a little out of tune with the times—there are still survivals of a past more loosely woven, there are disconcerting beginnings of a future yet unforeseen” (41). Quirky throwbacks like the Alberts, aloof from the city’s ambitions, are heralds of a future beyond view. Their double birthday awaits another birth.

Likewise, the meaning of Cather’s Venetian window never comes fully into focus: there is no definitive way “to make the picture complete”; the seat in the prow of the gondola is open to any passenger, any reader. The Venetian window offers a paradigm for the values held suspended here and elsewhere in Cather’s modernism: between authenticity and witnessing; naming and not naming; decline and renewal. In an echo likely to be missed, Cather’s story balances these tensions when Uncle Albert’s closing utterance “Even in our ashes” (63)—quoting Thomas Gray’s elegiac line, “E’en in our ashes live their wonted fires” (line 92)—recasts the opening sentence “Even in American cities . . .” The narrative moves between cities and ashes, embracing the polarities of glass itself, which erects the modern city from the base matter of molten sand and ash. The Venetian window, vestige of “a past more loosely woven,” is the hidden eye of the story’s revolutions: the fin-de-siècle artwork revitalizing centuries of glassmaking tradition, glimpsing through its opalescent medium and its Venetian subject “the disconcerting beginnings of a future yet unforeseen.”

NOTES

Research on this essay was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (most 104-2410-h-030-041-my2).