From Cather Studies Volume 13

Bicycles and Freedom in Red Cloud and Pittsburgh: Willa Cather's Early Transformations of Place and Gender in "Tommy, the Unsentimental

Over the years, critics and scholars have often suggested that Willa Cather needed time to come to terms with Nebraska. Perhaps because of stories such as “Peter,” “On the Divide,” “A Wagner Matinee,” and “The Sculptor’s Funeral,” it has been tempting to think of “The Bohemian Girl” (1912) and O Pioneers! (1913) as marking the grand rapprochement of author and region. [1] But Cather’s artistic trajectory is more complex than this narrative admits. As early as 1896, when she moved to Pittsburgh in order to edit Home Monthly, the author was more than ready to reinvent her home country in ways that would eventually inform her greatest fiction. Bernice Slote observes in her essay accompanying Cather’s The Kingdom of Art that by “1896 Willa Cather had written nearly a half million words of criticism, self-analysis, and explorations into the principles of art and the work of the artist” (4). Marilyn Arnold points out that the seasoned author “proved herself an artist long before O Pioneers! appeared in 1913. Some of her very earliest stories have the earmarks of genius, and a good many of them before O Pioneers! are superb” (xiii). One of these stories is “Tommy, the Unsentimental,” which appeared in the August 1896 edition of Home Monthly. In this story, the “earmarks of genius” can be attributed to the way Pittsburgh helped Cather reinvent her hometown of Red Cloud. Eschewing early pioneer experience for her own recent memories, Cather celebrates a metropolitan town in the American West where a woman can ride bicycles, experiment with gender, and resist societal expectations. Like the cocktails that Tommy concocts for her older male friends in Southdown, the story is a heady mix of spirit and innovation that helps to explain how Red Cloud and Pittsburgh mattered to Cather’s emergence as a great American writer.

Before “Tommy” appeared in Home Monthly in 1896, Cather had published a handful of stories set in Nebraska, the two best being “Peter” and “On the Divide.” In these early works, Nebraska is a grim place of the past, marked by aridity, struggle, and futility. In “Peter,” we learn that father and son had settled in “the dreariest part of south-western Nebraska” where “there was nothing but sun, and grass, and sky” (5, 6). In “On the Divide,” the narrator describes the location of Canute’s “shanty” on “the level Nebraska plain of long rust-red grass that undulated constantly in the wind” (8). Life in such a region is positively pathological: “Insanity and suicide are very common things on the Divide. They come on like an epidemic in the hot wind season. Those scorching dusty winds that blow up over the bluffs from Kansas seem to dry up the blood in men’s veins as they do the sap in the corn leaves” (10–11). As Robert Thacker notes, “throughout these stories Cather is both direct and, apparently, embittered, seeing the prairie landscape as destroying its homesteaders’ spirit through its very vastness and the loneliness it occasions” (148). Susan J. Rosowski suggests that the challenge for the young author was “how to humanize an alien world” (16).

In the months after Cather graduated from the University of Nebraska, in June 1895, she must have felt ready for any challenge. An accomplished and respected journalist, she shuttled back and forth between Lincoln and Red Cloud, attending parties, visiting friends, writing pieces for the local newspapers, and riding her “wheel.” Cather was becoming one of the New Women who defined themselves and their freedom through what Janis Stout has called “masculinized styles” and, of course, the riding of bicycles.[2] A headline in the 31 May Lincoln Evening Call could have been written for the recent graduate: “The New Woman Riding into Freedom on the Bicycle” (3).

Fig. 1.1. Mary Miner, Willa Cather, and Douglass Cather, ca. 1895. Courtesy of

the Willa Cather Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society.

Fig. 1.1. Mary Miner, Willa Cather, and Douglass Cather, ca. 1895. Courtesy of

the Willa Cather Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society.

What would freedom look like for Cather? Would it, in some way, involve a bicycle? A column entitled “Literary Lincoln” in the 1 June 1895 Courier puts Cather “at the head of the list of the writers of Lincoln,” noting that “she has ideas and knows how to express them, and to express them well. As a critic she is fearless, and has the knack of seeing things as they really are, and of writing them so that other people may see them” (5). “I find this country looking like a garden,” she wrote to Ellen Gere and Frances Gere on 30 July 1895, “green and beautiful beyond words,” confiding, “I had great times riding my wheel in Lincoln and Beatrice. I have a hundred adventures to tell you” (#0019 Complete Letters).

In August, she landed a position as associate editor at the Lincoln Courier. Announcing her new position, the 3 August 1895 Courier called her “thoroughly original and always entertaining” (1). A new life in Lincoln was taking shape, but the fearless critic seems to have been unable to resist waging war against political corruption in the city. Fed up with the way the federal court was handing (or mishandling) the R. C. Outcalt embezzlement scandal at the Capital National Bank, the Courier’s fiery editorializing ran afoul of the presiding judge. The 13 December 1895 Lincoln Herald reported the finale for the editors: Col. W. Morton Smith has been fined $50 and fifteen days in jail by the federal court at Omaha, for the naughty things he said about the Outcalt case in his valuable paper. Miss Sarah Harris one of the editors was subpoenaed as a witness and Miss Willa Cather the third and best looking of the trio, quietly resigned her position and left the city. (1) Cather’s new professional life in Nebraska had fallen apart almost as quickly as it had begun. On 2 January 1896, writing to friends back in Lincoln, she headed the letter “Siberia,” offering a jaunty and satiric report of a New Year’s dance that included “the elite and bon ton of Red Cloud” before concluding that “one of the charms of the Province is that one gets indifferent toward everything, even suicide” (#0021 Complete Letters). The Nebraska Cather knew so well had become “Siberia,” an alien world that the ambitious young journalist could not civilize.

Fate, looking very much like publisher James Axtell, provided the answer. When Axtell offered her the position of managing editor of Home Monthly in Pittsburgh, she seized the opportunity. After feeling trapped in “Siberia,” she could save face by escaping to a world that held more opportunities than the one she was leaving. She had all the skills necessary for the job and the opportunity to go east seemed especially attractive. When she arrived in Pittsburgh on 26 June 1896, Cather wrote to Mariel Gere, noting the hills, “clear streams,” and trees east of Chicago (#0025 Complete Letters). “The conductor saw my look of glee,” Cather wrote,“and asked if I was ‘gettin’ back home.’” Describing Pittsburgh as the “City of Dreadful Dirt,” she quickly realized that fate had carried her far beyond Nebraska.

But the conductor had spoken prophetically. As the days passed, Cather quickly discovered that Red Cloud and Pittsburgh echoed each other with a precision guaranteed to fuel the writer’s imaginative conceptions of home. Cather was making a momentous discovery, which would shape her best work for decades to come. Years later in a 1921 Nebraska State Journal interview, she explained, “When in big cities or other lands, I have sometimes found types and conditions which particularly interested me, and then after returning to Nebraska, discovered the same types right at home, only I had not recognized their special value until seen thru another environment” (Willa Cather in Person 40). In 1896 Cather looked about and identified a shared fascination with rivers, trolleys, manufacturing, musical culture, brick buildings, bridges, bicycles, and New Women. To an author already inclined to write fiction set in Nebraska, Pittsburgh materialized before her eyes as a kind of looking glass, a magic mirror that made it possible for Cather to look at the new world of Pittsburgh, dream of Red Cloud, and write “Tommy, the Unsentimental.”

As she surveyed her new home, the author studied a formidable metropolis of manufacturing. The impressive trolley system that had “carried more than 23 million passengers” in 1888 was expanding (Tarr 31). Electric power had illuminated the city since 1887, thanks to George Westinghouse’s Allegheny County Electric Company (Tarr 34).

City Attorney Clarence Burleigh spoke rhapsodically about the city’s metropolitan accomplishments in the 14 April 1896 Pittsburgh Press: I come from that great human hive of industry and invention standing at Pennsylvania’s western gate, whose ground is sacred with our country’s history and glutted with nature’s richest wealth; whose manufactories are gigantic and legion with furnaces; whose never-quenched fires transform night into day; the hum of whose wheels is incessant, and whose finished products reach to every clime; a city with no industrial goal but perfection. (2) There is no doubt that Cather’s imagination was stirred by the “great human hive,” but she must have been surprised by the way recollections of Red Cloud could mingle with her experiences of Pittsburgh.

Although Pittsburghers would probably have laughed at the notion, Cather knew that Red Cloud newspapers often invoked the terms “metropolis” and “metropolitan” when they discussed local progress in Webster County.[3] She would have recognized that Burleigh’s vision of Pittsburgh “standing at Pennsylvania’s western gate” echoed an oft-used epithet from back home. As the 28 August 1885 Chief explained, Red Cloud held “the proud distinction of being the metropolis of the Great Republican Valley and the Gate city thereto” (5). When Cather noted the many examples of progress in one “gate city,” she could easily summon up echoes in the other “gate city.” Red Cloud newspapers had made the case for metropolitan progress time and again as she was growing up. Cather would certainly recall the rhetoric of the 20 April 1888 Chief: Red Cloud is going to be a mighty live town this year, and is already putting on signs of great activity. Two new railroads, a street railway, a creamery and several manufacturing institutions will go far to make her the beau ideal city of the valley and don’t you forget it. No other city or town in the valley can boast of a street railway, electric lights and numerous other enterprises. (1) Only eight years after New York City first installed electric lights and nearly fifty years before the Rural Electrification Act, the Chief could boast justifiably of the town’s electrified illumination, an undeniable sign of metropolitan progress. Well aware that such declarations about a town of some three thousand citizens on the Great Plains would never impress citizens from large American cities back East, the editors liked to season their prose with bursts of jocular bluster. “Whoop-la,” the 20 July 1888 Chief declared, “who says Red Cloud isn’t metropolitan. Water works, street cars, electric lights, five weeklies and one daily. Come to Red Cloud and be happy” (1).

Having left Red Cloud because she was most unhappy, Cather had good reason to reconsider her feelings about her Nebraska home. Growing up surrounded by civic boosting that was part reality and part myth, with a touch of hokum added for good measure, the ambitious young editor was ready to experience a new sense of pride in Red Cloud. Although much has been made of the way Cather’s earliest fiction laments the hard life of the pioneers, this emergent pride played a vital role in transforming the author’s personal and artistic relationship to Nebraska. After spending time in Pittsburgh, Cather was prepared to set aside the pioneer past and write a story set in a version of metropolitan Red Cloud.

Settling into her editorial position in the eastern metropolis, she returned to her beloved wheel and must have felt that her emergence as a New Woman was complete. On 4 August 1896, she reported to Mariel Gere that the work was hard but life in Pittsburgh offered distinct pleasures: “The only form of excitement I indulge in is raceing with the electric [street] cars on my bicycle. I may get killed at that, but certainly nothing more” (#0028 Complete Letters).[4] In risking life and limb on her wheel, Cather embodied the modern ambition of the New Woman while adapting to her new urban life. As Virgil Albertini explains, Cather “was astride her own private machine, which gave her the opportunity to travel cheaply, to enjoy the exhilarating freedom of mobility, to have exercise and possible camaraderie, and to test her stamina and speed with the electric cars” (14).

Later that fall, Cather set out on a cycling trip through the Shenandoah Valley that allowed her to explore what would become an abiding disposition. James Woodress comments on this cycling adventure: “Among the several polarities that pulled at Cather all her life was the attraction of the eastern mountains against the tug of the prairie of her adopted state” (112). By the summer of 1896, Cather the cyclist was beginning to race imaginatively between Red Cloud and Pittsburgh, between East and West, feminine and masculine. The New Woman had discovered a new kind of freedom.

Needless to say, Cather was part of a global phenomenon. In 1896 Londoners were celebrating the ten-year anniversary of the invention of the safety bicycle. From London to Estonia to Red Cloud and Pittsburgh, people were forming bicycle clubs.[5] In the United States, ordinary riders joined the League of American Wheelmen. Readers of the New York Times saw regular features on the sport—“Among the Wheelmen” and “Gossip of the Cyclers”—that were replicated all over the country in places like Red Cloud, Lincoln, and Pittsburgh.

There was much to talk about, but the subject of women and bicycles inspired the most debate. Annie Kopchavsky, known to the world as Annie Londonderry, embodied the conversation for many people when she completed an around-the-world cycling trip in 1895. Married with three children at the time, Londonderry was rewriting the Victorian narrative of female ambition and hardiness. Evan Friss observes, “The debates about female cyclists spiraled into a national discussion, encompassing a range of issues such as femininity, Victorian respectability, and physical health” (161). In the midst of this “discussion,” as Ellen Gruber Garvey points out, “advertising-dependent magazines asserted a version of women’s bicycling that reframed its apparent social risks as benefits” (67). Sarah Hallenbeck notes that these “magazines provided an effective vehicle for promoting not only women’s bicycling in general but also a distinctly modern model of heterosexual desire, courtship, and domesticity” (xxiv).

No one in this debate was more dynamic than Frances Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, she told the story of learning to ride after the age of fifty and described her particular relationship with “Gladys,” her bicycle. Willard had a powerful message: “She who succeeds in gaining the mastery of such an animal as Gladys, will gain the mastery of life, and by exactly the same methods and characteristics” (28). The reviewer in the 18 May 1895 New York Times called it a “spicy little book” and praised Willard’s admonition: “all failure is from a wobbling will rather than a wobbling wheel” (3). With this admonition in mind, Hallenbeck suggests that Willard is “reinforcing her indirect claim that women need only confidence and persistence to achieve personal or social success in life” (117).

Fig. 1.2. Frances Willard and Gladys, her bicycle. Photograph from her book,

How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, Fleming H. Revell,

1895.

Fig. 1.2. Frances Willard and Gladys, her bicycle. Photograph from her book,

How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, Fleming H. Revell,

1895.

In the 1890s, women and bicycles were nothing short of revolutionary. As Gruber Garvey observes, “the new mobility the bicycle allowed offered freer movement in new spheres, outside the family and home—heady new freedoms that feminists celebrated” (72). Susan B.Anthony spoke to the fact directly in 1898: “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel” (qtd. in Sher 277). Admitting a preference for his horse but his delight in mounting a bicycle, Owen Wister claimed, “More than the trolley does the bicycle promise to fulfill for us the Declaration of Independence; women are become the equals of men, and the black and the Chinaman speed with them across the pleasant levels of Democracy” (qtd. in “Authors on the Wheel” 226–27). Writing from her own experience in the early 1890s, Grace E.Denison remembered the derision she and other female riders had experienced, but Denison declared a combat victory: “We lived down, or rather rode down, our enemies” (52). By the time Cather arrived in Pittsburgh in 1896, she was caught up in this revolutionary spirit.

She certainly came to the right place. Pittsburgh in the 1890s was positively buzzing about bicycles. Cyclists were everywhere. In 1898, as Friss points out, Pittsburgh had one bicycle shop for every “5,300 people (still more shops per capita than present-day Amsterdam). Pittsburgh was also home to a half dozen bicycle liveries, renting out bicycles” (25). The city’s newspapers were crammed with stories about bicycle races, clubs, riding apparel, winter riding, the dangers of cycling, proper pedaling instructions, famous cyclists, and the ongoing controversy over women cyclists. The Pittsburgh Dispatch offered “Gossip of the Cyclers” on a regular basis. A week or so after arriving in Pittsburgh, Cather could have read in the 11 July 1896 Pittsburgh Daily Post about James Hoar’s agonizing death from scorching, the popular practice of cyclists riding extremely fast (4). A couple of weeks later, the newcomer could have experienced the “Sunday Scenes at Schenley Park,” where, according to the 27 July 1896 Pittsburgh Gazette, “bicycles, single and tandem, shot in between the larger rigs, dodging like swallows just before a rain storm” (5). The popularity of such stories can be gauged by the announcement in the 14 August 1896 Pittsburgh Press: “WHEELMEN! Everything of interest and importance concerning cycling is to be found in THE PRESS” (11).

Fig. 1.3. Cover of Outing Magazine, August 1892.

Fig. 1.3. Cover of Outing Magazine, August 1892.

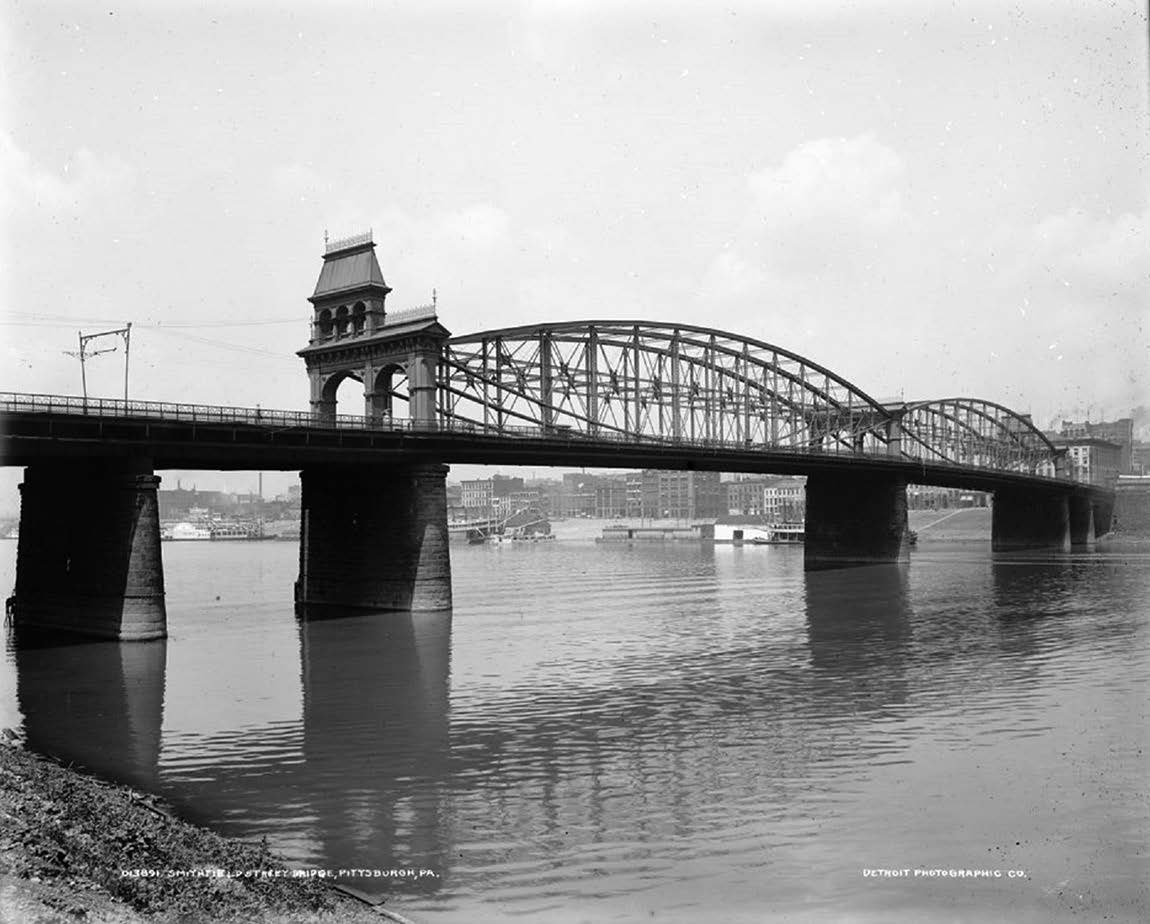

In 1890s Pittsburgh the most compelling cycling stories of the day were about Pittsburgher Frank Lenz, arguably the most famous cyclist in the world by the time Cather arrived in the city. In the pages of Outing magazine, Lenz linked his ambition to his Pittsburgh origins: “My wheel and I had become familiar with all routes within reach of Pittsburgh” (xx). Lenz had advertised his civic pride by setting out from the Smithfield Street Bridge on 15 May 1892 to pedal around the world.[6]

Completed in 1883, the same year the Cather family moved to Nebraska, the bridge symbolized Pittsburgh’s metropolitan status but must have conjured up memories of Red Cloud in Cather’s mind. In her youth, the local newspapers had campaigned for a substantial bridge over the Republican River that would symbolize the town’s prosperity. The writer who loved Shakespeare must have recollected how the Chief produced headlines such as “To Bridge or Not to Bridge” and “My Kingdom for a Bridge.”[7] By 13 April 1888, the newspaper was calling the town “one of the bright and shining lights among Western Nebraska cities,” boasting that “four years ago nothing but an old wooden bridge spanned the great Republican river south of the city, to-day one of the finest iron bridges in the west stretches across its placid waters, a monument to the enterprise of our city and county” (1). When Cather gathered her childhood friends to build a play-town in the backyard, her first project as mayor and editor of the enterprise was the construction of a bridge (Bennett 172–73). Now in Pittsburgh, her imagination already stirred by bicycles, Cather discovered more reflections of Red Cloud.

Famous or not, wheelmen were everywhere in Pittsburgh, but wheelwomen attracted the most critical attention. A steady stream of articles offered advice to women cyclists. Typical of the genre is “For the Fair Cyclist,” appearing in the 16 August 1896 Pittsburgh Press, which admonishes, “The very first ‘do’ is, do dress appropriately” (11). More than anything else, women cyclists should be concerned about appearances, or so many commentators suggested (Hallenbeck 43–52). As Cather worked at Home Monthly, the 30 July 1896 Pittsburgh Press reported, “A Chicago new woman ran down a man with her wheel. No gentleman would run down a woman, no matter who she is” (1). Women cyclists could be dangerous. Days later, in the 9 August 1896 Daily Post, Helen Ward described the battle between Charlotte Smith, president of the Woman’s Rescue League and crusader against the bicycle, and Willard, who “found her health in the revolutions of the two little wheels” (11). Six days later, a poem in the 15 August 1896 Pittsburgh Daily Post entitled “Sectional Characteristics” identified regional types of women based on what they carried when they rode their bicycles:

Fig. 1.4. Smithfield Street Bridge, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, ca. 1900. Detroit

Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division, LC-DIG-DET-4A09244.

Fig. 1.4. Smithfield Street Bridge, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, ca. 1900. Detroit

Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division, LC-DIG-DET-4A09244.

That the cycling girl of Texas

As she rides is not afraid—

She provides a pistol pocket

When she has her bloomers made;

That the bloomer girl of Boston

Always cool and wisely frowning,

Has a pocket in her bloomers

Where she carries Robert Browning;

That the Daisy Bell of Kansas,

Who has donned the cycling breeches,

Has a pocket in her bloomers

Full of woman suffrage speeches. (4)

Fig. 1.5. Red Cloud Bridge, ca. 1883. Courtesy of the Willa Cather

Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society. While in no danger of rivaling the verses of Dickinson or Whitman, the

poem does reveal the way cycling and women were linked in the popular imagination.

Women cyclists were dynamic, often unconventional, perhaps dangerous. Types were

real. Eastern women carried poetry. Western women carried pistols and fought for

equality. Cather may or may not have read these particular newspaper items, but

they help us appreciate the cycling conversation she was joining as she wrote

“Tommy.” The New Woman from Nebraska who indulged in racing street cars in

Pittsburgh was right at home.

Fig. 1.5. Red Cloud Bridge, ca. 1883. Courtesy of the Willa Cather

Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society. While in no danger of rivaling the verses of Dickinson or Whitman, the

poem does reveal the way cycling and women were linked in the popular imagination.

Women cyclists were dynamic, often unconventional, perhaps dangerous. Types were

real. Eastern women carried poetry. Western women carried pistols and fought for

equality. Cather may or may not have read these particular newspaper items, but

they help us appreciate the cycling conversation she was joining as she wrote

“Tommy.” The New Woman from Nebraska who indulged in racing street cars in

Pittsburgh was right at home.

Back in Nebraska, newspapers in both Red Cloud and Lincoln had given Cather ample opportunities to keep up with the latest cycling advice, news of clubs and races, stories of celebrity cyclists and local enthusiasts, and the ongoing debate over women and bicycles.[8] An article in the 2 October 1891 Chief proclaimed cycling “The Queen of Sports” (3). The 29 June 1894 Chief described the adventures and misadventures of the young men from the Bladen Bicycle Club who rode down to Red Cloud on a Sunday morning: “The boys all report a good time and are highly pleased with the way in which Red Cloud entertained them” (4). The 25 October 1895 Chief reported that Cather’s brother Roscoe was “recovering from a bicycle fall” (8). “American women are not walkers,” an article in the 19 July 1895 Chief declared, “but the cycle is perhaps even better suited to woman’s use than man’s and seems destined to add an outdoor element to the life of woman the world over” (2). An article in the 31 May 1896 Nebraska State Journal invoked Willard while arguing that the bicycle had helped “women” displace “ladies”: “Women and the bicycle now swarm the world over” (18).

A fine student and accomplished athlete, Louise Pound was one of these women. Early in her college career in Lincoln, Cather had been infatuated (perhaps in love) with Pound, who was also, among many other things, a remarkable cyclist (Lindemann 17). Albertini observes: “It was not uncommon for her as a member of a Century Club to ride one hundred continuous miles in one day. This active, ambitious, and talented woman earned her first Century Road Club bar in 1895 and her second in 1896, and in 1896 she received the Rambler Gold Medal for riding five thousand miles in one year” (13; Yost 484; Cochran 82). The 27 April 1895 Courier provides a sense of the athlete’s standing in the community after she set a single-day, long distance record: “On Saturday last, with an escort, Miss Louise Pound of this city, added another laurel to her reputation as one of the best lady athletes in the state by making a run of 111 miles on a bicycle” (12; Cochran 80–82). In 1896, as she contemplated a cycling heroine, Cather’s thoughts would have turned to the Lincoln celebrity she knew so well.As Albertini suggests,“If Tommy indeed does have a prototype, Louise Pound is a solid candidate” (16).

Fig. 1.6. Louise Pound with her Rambler bicycle, ca. 1893. Courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society.

Fig. 1.6. Louise Pound with her Rambler bicycle, ca. 1893. Courtesy of the

Willa Cather Foundation Collection, Nebraska State Historical Society.

Well aware that the summer was flashing by, the new editor of Home Monthly had good reason to be thinking about prototypes. She needed material for her publication and a story of her own seemed like the obvious course of action. Given her existing body of work and the focus of the magazine, a story of pioneer domesticity on the Nebraskan prairie would have been appropriate, but Cather’s thoughts shifted to Red Cloud in the 1890s. It was a career-changing discovery. From “Tommy” to The Song of the Lark and My Ántonia and on to “The Best Years,” written near the end of the author’s life, Cather’s reinventions of Red Cloud would be central to her vision.

Fascinated by the way that Pittsburgh is triggering this discovery, Cather explores her own awakening in the opening pages of “Tommy, the Unsentimental.” Having moved “back East,” Cather firmly locates the fictional town of Southdown in “the West” (473). The narrator implies a certain metropolitan vibe by placing Southdown in the context of “live western towns” inhabited by “active young business men and sturdy ranchers” who enjoy “cocktails” and “billiards” (474). Perhaps merging herself and Louise Pound in a composite prototype, Cather invents a professional heroine who works in the Southdown National Bank, occasionally needs to take a run “on her wheel,” and has recently spent a year in school back East where “she distinguished herself in athletics” (475). Tommy could easily be speaking for the author as she describes her recent epiphany: It’s all very fine down East there, and the hills are great, but one gets mighty homesick for this sky, the old intense blue of it, you know. Down there the skies are all pale and smoky. And this wind, this hateful, dear, old everlasting wind that comes down like the sweep of cavalry and is never tamed or broken. O Joe, I used to get hungry for this wind! I couldn’t sleep in that lifeless stillness down there. (475–76) Writing from the hills of Pittsburgh, Cather is being proleptic here, already imagining a homecoming in which she will share her new vision with “everyone.” The author of “On the Divide” was ready to praise the sky and the wind of Nebraska, a region now firmly located in the American West.

The resulting shifts in Cather’s artistic consciousness were radical indeed. In these moments, Cather was recasting her vision of Nebraska while realizing that remaking Red Cloud could be endlessly diverting. More theoretically, Cather was discovering the power of the palimpsest, a term referring to the ancient practice of scraping words from a piece of vellum and writing over the traces of the old text. As Sarah Dillon explains, the fact that the old writing often showed through the new led Thomas De Quincey to use the term in a figurative way to describe the way in which “our deepest thoughts and feelings pass to us through perplexed combinations of concrete objects. . . .” The adjective “involuted” describes the relationship between the texts that inhabit the palimpsest as a result of the process of palimpsesting and subsequent textual reappearance. The palimpsest is an involuted phenomenon where otherwise unrelated texts are involved and entangled, intricately interwoven, interrupting and inhabiting each other. Another word that describes this structure is the neologism “palimpsestuous.” (245) In “Tommy,” Southdown comes into view as an “involuted phenomenon,” a palimpsest that mingles bits of Pittsburgh and Red Cloud. Tommy’s enthusiasm for life in this live western town echoes the author’s awakened feelings. Indeed, Cather seems to have experienced a new and piquant pleasure in writing about Nebraska that would carry her through the rest of her career.

This palimpsestuous pleasure is on display as Cather maps the story’s setting. The narrator identifies the little town of “Red Willow, some twenty-five miles north, upon the Divide” (475). Twenty-five miles north of Red Cloud was Blue Hill. In creating this little palimpsest, Cather playfully exchanges Blue for Red. Hill becomes Will-ow, perhaps with a wink at “Willie and Willwese,” as Cather’s little sister Elsie dubbed the two women (Lindemann 24). Instead of a grim parsing of a pathological landscape, Cather becomes a “territorial colorist” while creating monikers for familiar places (Palmer 34–37). Over the years, many of the author’s readers have shared precisely this pleasure as they explore Cather’s involuted topographies.

In this mood, the narrator explains that Tommy’s “best friends were her father’s old business friends, elderly men who had seen a good deal of the world, and who were very proud and fond of Tommy” (474). Cather is here creating another sort of palimpsest, recasting for the first time in her fiction a group of adult friends from childhood that included Gilbert Einstein McKeeby, J. L. Miner, and Charles Wiener. Mildred Bennett points out “that every one of these gentlemen appeared later as important characters in Willa Cather stories” (24). Although Tommy does not show any heterosexual interest in the available men of Southdown, she finds genuine friendship with these “elderly” men. As the narrator goes on to explain,“She was just one of them; she played whist and billiards with them, and made their cocktails for them, not scorning to take one herself, occasionally” (474). Cather, of course, was writing from personal experience, making a case for a young woman’s freedom to enjoy male friendship. In 1896 the author was already beginning to sketch the involuted world of Thea Kronborg in The Song of the Lark.

Although Cather’s domestic partner, Edith Lewis, concluded that the stories written during this period “are an indication, I think, of how valueless this sort of writing can be,” scholars, when they discuss “Tommy” in any detail, have found value in the story’s approach to gender and sexuality (Lewis 42). Sharon O’Brien rightly concludes that the story “mocks the Victorian ideal of womanhood to which the Home Monthly was supposedly dedicated” (229). For Judith Butler, the central character is trapped in a Lacanian matrix “of prohibition, propriety, and cross-gender appropriations” (156). Gruber Garvey cogently argues that the story “plays out the bicycling woman’s threat to gender definition” and even offers “an alternative model of gender” (92). Noting Cather’s fondness for the work of J. M. Barrie and the short story’s obvious allusion to Barrie’s recent and popular novel Sentimental Tommy, Michelle Ann Abate explores the ways in which both works “present central characters who possess nonheteronormative sexualities” (470). Abate persuasively nudges the conversation away from binary categories and toward “emerging modernist forms of queer sexuality” (470). As Debra J. Seivert notes, “Tommy” is also a “literary ‘conversation’ about romanticism, sentimentality, and realism that would become fundamental to her own art” (104).

The notion of the palimpsest offers another way of moving this conversation forward. Some years ago, Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar argued that the great women writers of the nineteenth century “produced literary works that are in some sense palimpsestic” (73). In this vision, which at first glance seems applicable to Cather’s “Tommy,” an essential truth of gender might be glimpsed by the astute critic, but Dillon counters that the palimpsest is not simply a layered structure which contains a hidden text to be revealed. Rather it is a queer structure in which are intertwined multiple and varying inscriptions, in this instance both male and female. Whereas the traditional understanding of the palimpsest corresponds to a reading approach that seeks only to uncover or reveal, this more complex understanding . . . requires a more radical queer palimpsestuous reading. (257) “Tommy” invites such a reading in remarkable ways by offering the bicycle as an interpretive key in a palimpsestuous vision of Nebraska. The surprising thing for readers today and perhaps for Cather at the time is that the creation of the involuted topography helped the author begin to explore her own involuted and evolving notions of gender, sexuality, and identity.

With its opening paragraphs, “Tommy” drops the reader into this more complex vision. The central character is a strong-willed woman of business who has, according to the narrator, a “peculiar” relationship with Jay Harper, a relationship less than romantic, and something more exotic than mere friendship (474). Tommy and Miss Jessica discuss Jay, but most readers are probably still trying to determine who is talking about whom when the narrator declares, “Needless to say, Tommy was not a boy, although her keen gray eyes and wide forehead were scarcely girlish, and she had the lank figure of an active half grown lad” (473). As Butler observes, the “needless to say” is disingenuous (155). No reader would have suspected that Tommy is a woman, but many would have recognized that slang versions of “Tommy” in the 1890s could suggest everything from unruliness to prostitution to lesbian desire (Butler 154–55; Abate 478). In this bold way, Cather was introducing her Home Monthly readers to a world where gender is open to inquiry and experimentation.

What, after all, defines boys and girls? Eyes? Forehead? Figure? Sentiment? Clothing? Journalists in the 1890s were particularly fond of asking these sorts of questions. Typical of the genre is the aforementioned poem in the Pittsburgh Daily Post that proposed sectional characteristics. In the 19 July 1896 Pittsburgh Daily Post, Helen Ward offered an example of this genre that either uncannily anticipated or actually inspired Cather’s initial paragraphs and her description of Tommy’s eyes. An “old beau” opens Ward’s article by declaring, “Girls are known for their eyes” (20). After this gambit, Ward’s speaker proceeds to sketch different types of girls, moving from “the flirt” to “the sentimental type” to “the chum girl” (20). The old beau confesses he used to like the latter sort: She is the girl who is a match for you on all your expeditions. Will you go cycling, my pretty maid?” “Can you do a mile in 2:10?” she said. (20) It would be tempting to suggest that Tommy is a “chum girl” until the speaker describes “the talented girl,” who can do everything from sports to “setting a broken arm,” who “has kept wide awake and knows a little of everything” (20). The talented girl “goes in for sports,” but will not focus on them because she realizes there “are so many real things in the world for her” (20). This latter description comes closer to describing Cather’s wide-awake heroine, but it could never stand in for the complexity of Tommy’s evolving position over the course of the story.

Indeed, after examining this sort of popular journalism, readers of “Tommy” are better able to appreciate the way the author is questioning rather than applying contemporary gender types. The eastern girl, Jessica, is “a dainty, white, languid bit of a thing, who used violet perfumes and carried a sunshade” (476). In this initial description, Cather’s story seems to confirm that gender “types” are rooted in region, but readers quickly realize that it would be a mistake to assume that such “types” are stable. A little later, the narrator ostensibly explains why people call Theodosia “Tommy”: “That blunt sort of familiarity is not unfrequent in the West, and is meant well enough. People rather expect some business ability in a girl there, and they respect it immensely” (473). Is the narrator implying that gender is, in some senses, attained? Jay’s masculinity is certainly diminished in such a system. Tommy dismisses him as “a baby in business” (473). Further complicating Jay’s position in the story as a potential partner for either Tommy or Jessica is his carnation, which, Abate suggests, may highlight his “status as a queer character” (481).

At this juncture, Cather has set the stage for her cycling story, which ultimately illustrates Hallenbeck’s notion that women in the 1890s “drew from the bicycle in constructing new identities and arguments for and about themselves” (xiii). That Cather embraces this agenda is evident if one surveys the cycling stories published during the period. As Hallenbeck observes, “much fiction about bicycling—written by both men and women—simply emphasized heroines’ youth, beauty, appropriate femininity, and suitability for a match with a dashing male bicyclist” (79). Writing from Pittsburgh while looking back to Nebraska, Cather was aiming for “new identities and new arguments” as she introduced the story’s crisis.

Tommy gets a telegram from Harper, pleading with her to help him save his failing bank. The clock ticking, Tommy must figure out a way to get funds to Harper in time. Cather’s good humor shines through as Tommy declares,“There is nothing left but to wheel for it” (477). In this palimpsestuous moment, Cather was compressing her final summer days in Red Cloud and her thrilling rides through Pittsburgh streets. She may also have had in mind the (possibly apocryphal) story Roger Welsch rehearses of Louise Pound racing on her Rambler to rescue her brother Roscoe: At any rate, the story, which I treasure as the truth, goes that Pound jumped on her bicycle and pedaled as fast as she could to the den of iniquity to warn her brother before the arrival of the police, only to find when she arrived that Roscoe had already left the establishment. But she herself did not leave in time to escape being detained by the police, who would probably have been amazed and even scandalized to find a woman present. (x) Part mythmaking, part experiment, Cather’s palimpsestuous rescue scene invites the reader to reconsider the emergence of the New Woman in the 1890s.

At the same time, Cather was ready to engage the larger conversations about women and cycling that were going on everywhere from Red Cloud to Pittsburgh and, more particularly, the pages of Home Monthly. As Jennifer Bradley points out, Cather published nine articles about cycling during her tenure at the magazine, covering such concerns as damaged digestion, improved complexion, safe riding techniques, and the danger (for women) of unintended arousal.[9] With “Tommy” Cather was offering her own more complex and even radical contribution to the conversation.

Tommy’s ride is, as Albertini points out, “heroic” and “arguably possible even if she is burdened with abundant handicaps” (18). The narrator explains, “The road from Southdown to Red Willow is not by any means a favorite bicycle road; it is rough, hilly and climbs from the river bottoms up to the big Divide by a steady up grade, running white and hot through the scorched corn fields and grazing lands” (477). If we imagine Tommy riding a Rambler after the fashion of Louise Pound, completing the ride of twenty-five miles in less than seventy-five minutes, the feat seems worthy of notice in the local newspapers under “Wheel Notes.” Needless to say, Jessica does not measure up to this standard of heroism.

Tommy sums up her triumph in a fascinating rumination that expands on the inquiry into gender types: “Poor Jess. . . . Well, your kind have the best of it generally, but in little affairs of this sort my kind come out rather strongly. We’re rather better at them than at dancing. It’s only fair, one side shouldn’t have all” (478). Cather’s heroine believes in multiple “kinds” and “sides” expressed in the difference between cycling and dancing, West and East, the New Woman and the traditional lady, women who desire men and women who do not, and so on.

Cather was also, at this crucial juncture, reworking some of her Nebraska journalism from earlier that summer. Discussing the actress Emma Calvé, Cather had declared in her “Passing Show” column in the 7 June 1896 Nebraska State Journal: Volcanic emotions are all right on the stage, but they don’t go on a bicycle. Bicycles are for the age of steel in which Carmens and Calves belong not. Bicycles are not to be wooed by languorous glances or guitars or the Spanish melodies of Bizet; they are stiff and formal and uncompromising; they stand for the age of steel in which Carmens and Calves belong not. A bicycle insists upon being treated coolly and respectfully and bitterly resents arduous advance. (13) Perhaps we should think of Tommy as a new sort of heroine of the West invented for an age of steel perfected in Pittsburgh.

But this passage also raises provocative questions about the place of sexuality in Cather’s story. In the newspapers and magazines of the day, critics of women cyclists were concerned about the potential for arousal. As Hallenbeck observes, pundits fretted over “friction,” implying that “both the high pommel and any contact between the rider’s body and her saddle might signify a female rider’s depravity” (54). Sue Macy points out that the November 1896 Medical Record was more than ready to consider cycling “a means of gratifying unholy and bestial desire” (44). In this context, Cather’s notion of the bicycle resenting “arduous advance” may be juxtaposed with Tommy’s choice of the bicycle over dance. Perhaps Tommy, as she identifies with bicycles, is rebelling against any imposed notions of sexuality?

Even staid Pittsburgh housewives, familiar with popular cycling stories, might have been able to overlook such radical ideas if the story had ended in the “proper” engagement of Tommy and the rescued Jay. Fans of Annie Londonderry would have noted that her extraordinary cycling adventures did not preclude her from embracing marriage and children. But Cather offers no such consolation. Tommy is firm with Jay: “I wish you’d marry her and be done with it, I want to get this thing off my mind” (479). Thinking in terms of gender, Jay feels like a failure.“You almost made a man of even me,” he declares (479). Tommy questions the quality of her own life: “Since I have known you, I have not been at all good, in any sense of the word, and I suspect I have been anything but clever” (480). The statement is probably more epiphany than confession. A kind of reckoning has occurred.

What to make of such an ending? Scholars have offered a variety of interpretations. Arnold, with good reason, sees “emerging in this story the pattern of the strong female and the weaker male that appears in several of Cather’s novels” (10). Butler argues that “Tommy’s cycling becomes the argument by which Jessica’s desire, if it was ever for Tommy, becomes successfully deflected” (158). In this reading, the story culminates in “the reflexive sacrifice of desire, a double-directional misogyny that culminates in the degradation of lesbian love” (161). Abate concludes that Tommy’s resistance to sentiment marks “a movement closer to the more outwardly reserved but also self-consciously erotic form of lesbian identity that would emerge in the twentieth century” (479).

The story’s ending may be even more rebellious than these readings suggest. Bradley identifies a clear message “that those women willing to sacrifice relationships with men can find new independence” (58). Why, after all, would any reader want to see talented Tommy attached to Jay? But what if Cather is also suggesting that women willing to sacrifice certain relationships with women can find new independence? Why, for instance, would any reader want to see talented Tommy attached to Jessica? Far from deflecting desire as Butler suggests, the cycling adventure may serve to clarify Tommy’s independence. Gruber Garvey puts it well: “A life of fast riding in the larger sphere of action and Westernness is clearly superior to either Jay’s world of incompetence or Miss Jessica’s adjoining world of decorum” (94). Perhaps Tommy will find a partner, or perhaps she will determine that she needs no partner. In any event, her character and abilities suggest a future that looks less like a settled life in Southdown and more like the life of Louise Pound, who became an accomplished scholar, the first woman to serve as president of the Modern Language Association, and the first woman to be inducted into the Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame.

In fact, a closer examination of the final scene between Tommy and Jay reveals Cather’s explicit—and even moral—framework for this finale. Tommy’s explanation to Jay that Jessica is “your kind” is palimpsestuous, suggesting (simultaneously) something about “types” of women and men, mental and physical capabilities, ambition, and, of course, sexuality. In so doing, the story offers an early glimpse of what Marilee Lindemann has called Cather’s “queering of America,” “a process of making and unmaking, settling and unsettling that operates at times on the surfaces and at times on the deep structures of her fiction” (4). Tommy is emphatic about her part in this process: “We have been playing a nice little game, and now it’s time to quit. One must grow up sometime” (479). In Barrie’s Sentimental Tommy, the young man is unwilling to grow up. In Cather’s story, the young woman has grown up, does not claim the man, and argues that maturity is all about self-knowledge and an honest response to the complexities of gender and sexuality.

At the end of the story, Tommy embodies an independence more radical than Anthony and Wister could have imagined for women who ride bicycles. Like Denison, Tommy seems ready to “ride down” her adversaries, having discovered what it means for a woman to grow up at the end of the nineteenth century. Cather could have come across the notion in Red Cloud just before she left for Pittsburgh. The 8 May 1896 Chief “Wheel Notes” counselled: “Learn how to ride correctly, and afterwards ride to gain your own approbation. Never mind what others think about it” (7). Here, in the author’s first palimpsestuous recasting of life in Nebraska inspired by her arrival in Pittsburgh, Tommy discovers what it means to gain her own approbation, a revelation Cather was anxious to claim for herself and endorse as maturity.

NOTES

With thanks to the publishers and the editors of this volume, I adapt and expand upon portions of this essay that appear in my book Becoming Willa Cather.