From Cather Studies Volume 13

"The Most Exciting Attractions Are between Two Opposites That Never Meet": The City behind Cather's Pittsburgh Classroom

Comparing Willa Cather and Andy Warhol is like comparing apples and amphetamines. Within her lifetime, Cather crafted twelve novels, novels that feel less written than carved, full of precisely controlled prose that illuminates the nobility and fragility of human experience in a manner both timeless and intimate. Warhol, conversely, might make as many as twelve paintings an hour, obliterating craft altogether through a silk-screening process he was drawn to because it was “quick and chancy,” adjectives never attached to anything Cather created. Had she survived long enough, Cather would likely have hated Warhol’s work.[1] In “The Novel Démeublé,” she insisted, “One does not wish the egg one eats for breakfast, or the morning paper, to be made of the stuff of immortality” (44), yet such insubstantial phenomena were Warhol’s preferred subjects, and, in A Boy for Meg (1961), 129 Die in Jet (Plane Crash) (1962), and Tunafish Disaster (1963), he literally made high art from the morning paper. Throughout his career and via a multitude of media, Warhol approached the disposable as if it were immortal, goading audiences into pondering the significance of cheap, low-quality culture that Cather dismissed as, at best, mere amusement. Fundamentally, the two artists had opposite views on artistic representation: whereas Cather promoted meaning over things, Warhol, whose aesthetic trademark was serialization of the same, strove for the inverse, insisting, “The more you look at the same things, the more the meaning goes away, and the better and emptier you feel” (Popism 50).

The epochal distance between them is not so much because of their different places in time—their lives actually overlapped—but because of their very different vantages on time. Cather’s aesthetic affinities ran backward, exemplified by the line she drew with the title of her 1936 collection of essays Not Under Forty. For Cather, there was, temporally speaking, a right side of history and it was the other side of 1922 (or thereabouts). “It’s for the backwards,” Cather insists in the book’s prefatory note,“and by one of their number, that these sketches were written” (v). In no way am I suggesting that Cather was anachronistic, outdated, or otherwise fusty, only that her gaze drifted rearward, looking to the past in order to make sense of the present. Warhol, conversely, looked to the future: “We were seeing the future and we knew it for sure.” He says in Popism, his memoir of the 1960s,“We saw people walking around in it without knowing it, because they were still thinking in the past, in the references of the past. But all you had to do was know you were in the future, and that’s what put you there” (40). Unlike Cather, who was suspicious of technological progress, Warhol’s work embraced it as an ideal, from the silver walls of his New York studio, known as the Factory, which he said were the same color as the space program, to the mass-production methods he emulated through his painting process.

Despite the aesthetic chasm separating Andy Warhol and Willa Cather, they share a surprising number of critical confluences. Some, such as the renegade “a” at the end of their names that both dropped during adolescence—Cather picked hers up again, but Warhol never went back to being Andrew Warhola—are more curious than profound, whereas others can be quite revealing. Consider, for example, their complicated relationships to gay identity. While both artists maintained decades-long same-sex partnerships, Warhol with Jed Johnson and Cather with Edith Lewis, their queerness is frequently debated if not discounted altogether. With Cather, it’s due to an absence of any public proclamation of her lesbianism; Warhol’s gayness, on the other hand, gets lost in too many contradictory signs. Contending that Warhol was asexual, biographers and critics frequently point to statements like, “Fantasy love is much better than reality love. Never doing it is very exciting. The most exciting attractions are between two opposites that never meet” (Philosophy 44). Such assessments, however, are misguided as they confuse a discomfort with sex for an absence of sexuality and, more significantly, ignore the fact that Warhol habitually lied. The important point is that gay desire permeates Warhol’s life and work, yet his queerness, like Cather’s, remains somehow simultaneously both obvious and opaque.

Putting Willa Cather and Andy Warhol in conversation with one another reveals an infrathin kinship, “infrathin” being Marcel Duchamp’s word for the meaningful absences shared by distinct but related phenomena, the warmth of a seat recently vacated, for instance, or the affinity between two items made from the same mold.[2] It’s a goofy, quasi-mystical concept offered up by an artistic charlatan, but it’s useful here as the correlations between Cather and Warhol, two vastly different artists, are so eye-opening and, frankly, fun to ponder, they should not be dismissed as mere coincidence. Indeed, considering Cather in a Warholian context, and vice versa, offers new perspectives on two canonical and hyperanalyzed artists. Cather’s closeness in time to Warhol, for example, shows that she was within spitting distance of postmodernity—a direction in which she would have happily spit—and Warhol’s closeness to Cather expands his artistic lineage in surprising ways. While I do not promise the ideas that emerge for this exercise will always be useful in a scholarly sense, I am convinced they are always worth pondering.

Of the correlations between them, the easiest to discern is geographic as both Cather and Warhol spent crucial years in Pittsburgh. Cather’s Pittsburgh experiences are on display throughout this volume, but Warhol’s Pittsburgh roots warrant some explanation as, in many ways, they have been effaced by his close association with New York (just as Cather’s Pittsburgh experiences are frequently overshadowed by her association with Nebraska).[3] Warhol’s parents, Andrej and Julia Warhola, moved to Pittsburgh from Slovakia in 1914 and 1921 respectively, settling in a Rusyn immigrant neighborhood. Born Andrew Warhola on 6 August 1928, Warhol was the youngest of three boys—a sister died before his parents moved to the United States—and it was clear from the first that he was different. A hypersensitive child who preferred the company of girls, his sensitive nature was made even more so by a traumatic bout with Syndenham’s Chorea, which struck in third grade. Also known as St. Vitus’ Dance, the condition causes uncontrollable jerking movements of the limbs, and it rendered Andy bedridden for long stretches of time, further alienating him from peers while strengthening his connection with his mother. About this time and perhaps accentuated by the Chorea, Warhol’s skin lost pigmentation, leaving him with patchy spots on his face and initiating a lifelong belief in his own ugliness.[4] Throughout his years in Pittsburgh, Warhol went to mass, conducted in Slovakian at St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church, multiple times a week with his mother. He routinely attended mass throughout his life, often sneaking away from the debauchery of the Factory to attend mass at St. Vincent Ferrer Parish on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, again with his mother, who moved to New York in 1951 to live with him. He attended Schenley High School in Pittsburgh’s North Oakland neighborhood, and while he said he was completely ostracized in high school, peers remembered Andrew Warhola as an eccentric-but-well-liked classmate. He graduated in 1945, his senior yearbook photo captioned “genuine as a finger print.” He went on to study commercial art at Carnegie Tech, earning a pictorial design degree in 1949 and moving to New York less than a week after his graduation.

Cather’s Pittsburgh doesn’t often dovetail with Warhol’s largely working-class experience of the city, but they both felt a strong connection to the Carnegie Institute complex. Cather was enamored with the Carnegie Library—“they have all the books in the world there I think,” she wrote to Ellen Gere—and she frequently discussed the Carnegie Museum and its exhibits in Home Monthly and the Pittsburgh Leader. As for Warhol, when he was six, his father bought a house in a middle-class, Lower Oakland neighborhood about a mile from the Carnegie Museum and Library, and Andy often spent his days there, thumbing through books or roaming the museum’s galleries—he was especially fond of the Hall of Casts and its replicas of famous statues. It was the Music Hall, however, that was especially important to both of them. Being a music lover, Cather frequented the Carnegie Music Hall, going there on her second night in Pittsburgh and later using the space for a setting in “Paul’s Case.” “[Cather] put a little of herself into the title character in ‘Paul’s Case,’” James Woodress suggests in Willa Cather: A Literary Life, “whose spirits were released by the first strains of the symphony orchestra when he ushered at Carnegie Hall” (46). And it was in that same Carnegie Music Hall that Andrew Warhola took his first art class. Every Saturday from the 1930s up through the 1980s, three hundred Pittsburgh children streamed into the Carnegie Music Hall to take art classes with Joseph Fitzpatrick, a local artist and flamboyant character. As part of the class, students drew what they had seen earlier that week on Masonite board with crayons, after which Fitzpatrick invited ten exceptional students on stage to share their work with the auditorium. Andrew Warhola, a fixture in the class in the late 1930s, was frequently one of the ten chosen to share their work on the Carnegie Music Hall stage, his first encounters with artistic recognition, at least outside of his family, in a lifetime full of them. The influence of Joseph Fitzpatrick’s classes on Warhol cannot be overstated.

Isabelle Collin Dufresne, better known as Factory Superstar Ultra Violet, suggested Warhol learned other, extra-artistic lessons at those Saturday morning classes in Carnegie Music Hall: “Several times he mentioned two youngsters who arrived in limousines, one in a long maroon Packard and the other in a Pierce-Arrow. He remembered the mother who wore expensively tailored clothes and sumptuous furs. In the 1930s, before television and with no glossy magazines for poor families like Andy’s and few trips to the movies, the art classes opened a peephole for Andy to the world of the rich and successful. He never forgot what he saw” (qtd. in Bockris 50). Cather, too, learned something about wealth and wealthy people while living in Pittsburgh. She had known rich people in Red Cloud, but their fortunes were meager when compared to the Fricks, Carnegies, and Mellons of Pittsburgh, and, like Warhol, making sense of such unearthly fortunes affected her greatly. Ultimately, the two artists came to similar conclusions about the importance of money while placing very different values on the conclusions they came to: Cather ruefully acknowledged the importance of money while Warhol gleefully painted dollar bills when told he should paint what he loves. In each instance and despite the contrary values placed upon it, money played a significant role in their aesthetic worldviews. For Cather, money complicated artistic endeavors.[5] “Economics and art are strangers,” she said. Whereas for Warhol, money was the point: “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art” (Cather, On Writing 27; Warhol, Philosophy 92).

While they expressed contradictory ideas about the value of commercialism, Cather and Warhol’s career trajectories follow a similar arc in that both became “fine artists” after first achieving success in the commercial world. Warhol relocated to New York in 1949 to work as a freelance illustrator and draughtsman, and his success in advertising over the next decade was considerable, becoming the most highly sought-after illustrator on Madison Avenue and earning more than one hundred thousand dollars annually. In addition to illustrations for Glamour and other high-profile fashion magazines, Warhol designed Christmas cards, book jackets, and numerous album covers for Columbia Records, but his most lucrative and notable work during the 1950s was for the shoe company I. Miller. While Warhol had “high art” aspirations from the beginning, commercial work occupied most of his time during his first decade in New York, and his personal work, which employed the same blotted-line technique that was his trademark in the advertising world, was rarely exhibited and even more rarely purchased. Nevertheless, these years were crucial for Warhol as he built a professional infrastructure that would later support his outsized notoriety and productivity. On the one hand, he developed a network of influential people, always being careful to make the right impression on them, whether in his performance of self—in the advertising world, Warhol was known as “Andy Paperbag” due to his deliberately quirky habit of carrying his work in cheap paper bags—or by leaving little gifts with people so they would better remember him, a trick he picked up from his Slovakian mother. Just as important, Warhol developed professional routines during these years and learned how to meet deadlines and be productive when he did not feel like it. Indeed, the relentless creativity that characterizes his later fine art career was rooted in his early commercial work.

Cather had earlier made the same move from Pittsburgh to New York, but that move was preceded by her great relocation—there were a few—from Nebraska to Pittsburgh a decade earlier, an event that more closely resembles Warhol’s relocation to New York. Like Warhol, Cather was a young twentysomething with high art aspirations, but her work as an editor with The Home Monthly and other publications occupied most of her time and energy. Regardless, these years, as they were for Warhol, were crucial to her later high art success, as Katherine Byrne and Richard Snyder suggest in Chrysalis: Willa Cather in Pittsburgh: “Through her journalistic work, as she involved herself in the busy social and cultural life of Pittsburgh, she began to widen her horizons and to acquire the necessary discipline for writing daily” (ix). Of those horizons being widened, Cather’s growing collection of influential associates, people who would be instrumental to her success as an author, was an especially important development during her Pittsburgh years, almost as important as the work ethic and marketing acumen she acquired and refined while working for commercial periodicals. Cather, like Warhol, became a successful and highly regarded artist only after first learning how to make a living (while also acquiring a taste for personal comfort with a dash of luxury).

Working for The Home Monthly and other popular publications gave Cather, in the words of Peter Benson, “practical experience in the tough business of writing for the popular taste” (246). As disdainful of popular literature as she was, Willa Cather was keenly aware of, and, at least on occasion, enjoyed the business of being Willa Cather. She wanted to be successful and she wanted to be known, no matter how strongly she may have insisted otherwise. Nowhere is this clearer than in her switch from Houghton Mifflin to Knopf as the publisher of her work. In “‘As the Result of Many Solicitations’: Ferris Greenslet, Houghton Mifflin, and Cather’s Career,” Robert Thacker shows that while with Houghton Mifflin, Cather was deeply involved in the presentation and promotion of her novels, that “she both asserted the worth of her writing and concurrently offered advice on matters of marketing, defining possibilities, pursuing reviewers, building upon the attention her work had received and was continuing to attract during the 1910s” (375). And the move to Knopf was, fundamentally, driven by advertising concerns, Cather feeling that Houghton Mifflin never sufficiently distinguished her from their other authors and offerings. In a telling moment in a letter to Greenslet, Cather writes, “I think the recognition of the public and reviewers has outstripped that of my publishers” (Selected Letters 275), a statement that demonstrates her awareness that not only was she in the publishing business, she was herself a business (or, in more contemporary terms, a brand).

Working for McClure’s and working for I. Miller shoes respectively, Cather and Warhol learned the importance of meeting deadlines, reading markets, and generating content even if the mood didn’t strike. They developed creative routines and a sophisticated appreciation for audience by expressing themselves professionally at the behest of other people. The artist with great ideas and no discipline is a cliché, one that both Cather and Warhol managed to avoid. Yet neither “sold out,” which happens the other way around, when fine artists compromise their vision for commercial reasons. Cather and Warhol, rather, bought in, developing professionalism and discipline before pursuing an artistic vision. Instead of thinking of them as commercial artists turned high artists, perhaps it would be better to think of them as employees transformed into artistic executives, wholly in control of their products and promotion. Contrary to the romantic notion of the transcendent artist separate from market concerns and popular opinions, Cather and Warhol learned how the real world operated and then fit their respective talents into it.

Had Cather and Warhol ever met, their echoing experiences as commercial artists would have given them much to talk about, much more than their mature work as fine artists. And the idea of them meeting is not so absurd as it seems. As mentioned earlier, Andy Warhol and Willa Cather’s lives did overlap, which means, for a short while at least, they read and responded to the same headlines. “The atomic bomb has sent a shudder of horror (and fear) through all the world,” Cather wrote in August of 1945, “and one’s own affairs seem scarcely worth thinking about” (Selected Letters 652). The same day that first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Andy Warhol celebrated his seventeenth birthday. All told, Willa Cather and Andy Warhol were alive simultaneously for just short of two decades—when Cather, fifty-four years older than Warhol, died in her Park Avenue home in April of 1947, eighteen-year-old Andrew Warhola was a student at Carnegie Tech planning his first visit to New York City. However briefly, Cather and Warhol were, in the most generous possible sense of the word, contemporaries.[6]

Willa Cather and Andy Warhol’s temporal proximity is best illustrated through their separate and truly fantastic encounters with Truman Capote, who is a sort of missing link between them. According to an essay Capote began writing the day before he died, he first met Willa Cather one snowy day around 1945 in the New York Society Library (“Willa, Truman. Truman, Willa”). Unable to hail a taxi, Capote went for tea with “the blue-eyed lady”—he did not yet know it was Cather—whom he had seen at the library before, and, after expressing his love for My Mortal Enemy, Cather informed him that she was its author. Previously, in the “Conversational Portraits” portion of his 1980 collection Music for Chameleons, Capote mentioned his relationship with Cather and her partner, Edith Lewis, reminiscing, “I often sat in front of their fireplace and drank Bristol Cream and observed the firelight enflame the pale prairie blue of Miss Cather’s serene genius-eyes” (161). Even earlier, in a 1967 interview with Gloria Steinem, Capote identified his encounter with Cather as a true frisson in his life, calling Cather “one of my first intellectual friends . . . the first person I’d ever met who was an artist as I defined the term, someone I respected and could talk to” (97).

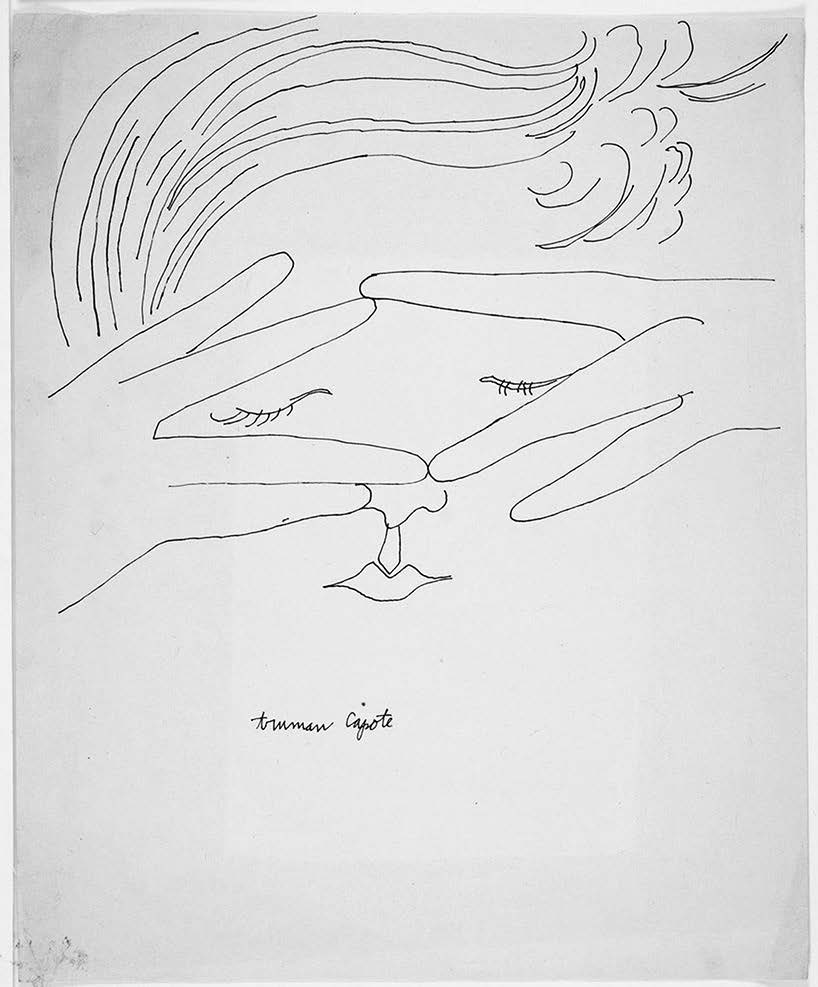

Had Cather lived another year, Truman Capote surely would have told his friend Willa about the strange fan mail he was receiving from an Andrew Warhola of Pittsburgh. During his first trip to New York in 1948, Warhol encountered a blown-up version of Truman Capote’s curiously erotic jacket photo for Other Voices, Other Rooms: “Twenty-year-old Andy was instantly taken with the image of the 23-year-old Truman.” Warhol biographer Victor Bockris wrote, “He was everything Andy wanted to be. He lived in New York and gave dinner parties for Greta Garbo and Cecil Beaton in his boyfriend’s apartment. He was young, attractive, talented, glamorous, rich and famous” (73). Andy became obsessed. (See figure 6.1 of Truman Capote by Andy Warhol.) According to the painter Philip Pearlstein, who attended Carnegie Tech with Warhol and was his first roommate in New York, “Every few days for several weeks Andy would put a drawing with a note expressing his wish for a meeting [with Capote] in an envelope filled with ‘fairy dust,’ sparkling bits of colored foil that flew out when the envelope was opened.” When Warhol moved to New York a year later, he loitered outside Capote’s apartment, hoping to “accidentally” run into the writer, and at one point, actually finagled his way into Capote’s home, getting the author’s mother to let him in. She, however, simply wanted someone to drink with. When Capote came home to the scene—Andy sharing his troubles with an inebriated Mrs. Capote—he humored Warhol because, in Capote’s words, “He seemed one of those helpless people that you just know nothing’s ever going to happen to, just a hopeless born loser, the loneliest, most friendless person I’d ever seen in my life” (qtd. in Bockris 91).

Fig. 6.1. Andy Warhol (American painter, printmaker, and filmmaker, 1928–

1987), Truman Capote, ink on printing paper, ca. 1954. ©

2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Fig. 6.1. Andy Warhol (American painter, printmaker, and filmmaker, 1928–

1987), Truman Capote, ink on printing paper, ca. 1954. ©

2019 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York.

All this time, Warhol had been sending Capote illustrations, illustrations that would provide the basis for Warhol’s first solo show in New York, “Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote.” The show opened at the Hugo Gallery on 16 June 1952, and in an Art Digest review James Fitzsimmons claimed, “[T]he work has an air of preciosity, of carefully studied perversity. Boys, tomboys and butterflies are drawn in pale outline with magenta or violet splashed here and there—rather arbitrarily it seems.” According to the gallery owner, David Mann, Capote and his mother did come to look at the work, but they made sure Warhol was not there when they did. Mann remembered that both had nice things to say about the drawings, yet Capote did not buy any pieces, nor did he commission Warhol to illustrate any of his future work, which was what Warhol had really wanted to accomplish through this show. Ultimately, none of the drawings sold, and the show was mostly ignored as this was still the era of Abstract Expressionism, and Andy’s “sissy” drawings did not conform to the prevailing macho aesthetic.

That Warhol’s first solo show drew on literary inspiration makes sense because drawing scenes from books was familiar to him. Robert Lepper, one of his instructors at Carnegie Tech, frequently had students read and illustrate significant literary works. “Andy excelled at the task.” Bockris writes, “He began to draw and paint a series of large blotted-line pictures that showed an intelligent understanding of what the books were really about, and a star ability to go straight to the heart of them and choose an image that would capture their essence” (70). One such illustration, Warhol’s drawing of the Huey Long character in All the King’s Men, still hangs in the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh. It was another instructor, however, who asked Warhol, sometime in 1947 or ’48, to read and illustrate Willa Cather’s “Paul’s Case.”[7] Howard Worner, according to Warhol’s classmate Bennard Perlman, emphasized the practical aspects of drawing and, toward that end, moved the story’s climax from Newark to nearby Panther Hollow Bridge, so that students might study the site and represent it from different angles. Perlman recollected: When the completed illustrations were tacked up on the wall for a critique, there were numerous examples showing the figure of Paul silhouetted in the dazzling headlight of an onrushing locomotive, of his body in midair as the train sped by, of his lifeless form sprawled on the ground below. And then there was Andy’s illustration—a striking red blob of tempera paint. Standing before it, Professor Worner turned to the class and observed: “It could be catsup,” to which Andy replied, in a nearly inaudible voice, “It’s supposed to be blood.” (157) Truman Capote surely would have loved this story, and had Warhol known about his obsession’s affection for Willa Cather, he surely would have shared it with him. Perhaps then it would not have taken until 1972, when Rolling Stone magazine hired Andy Warhol to interview Truman Capote, for the two to become the close friends they became.

As fun as the near miss is to ponder, Warhol’s reaction to “Paul’s Case” is worth considering on its own terms. Warhol grew up on middle-class Dawson Street in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, which bears a striking resemblance to Cordelia Street in “Paul’s Case,” and, like Paul, Warhol shared a desire to escape the mundane circumstances of his Pittsburgh upbringing: turning onto Cordelia Street, Paul felt “a shuddering repulsion for the flavourless, colorlessness mass of every-day existence,” and Dawson Street was the sort of place Warhol was talking about when he said “being born is like being kidnapped. And then sold into slavery” (Philosophy 96). Paul and Andy also shared numerous traits, such as their aversion to physical contact, their fascination with fame, and their belief in the redemptive power of money. Paul and Andy were a pair of dandies, valuing experience for the degree of its artifice rather than the depth of its authenticity—like Andy, Paul believed “the natural nearly always wore the guise of ugliness, that a certain element of artificiality seemed to him necessary in beauty” (179). And all this is in addition to the geographic concurrence, from their shared interest in the Carnegie’s Hall of Casts to the Music Hall where Paul found aesthetic release and young Andrew Warhola’s love of painting incubated. And, finally, Warhol also wanted to escape Pittsburgh and pursue beauty and glamour in New York, only he was afraid tragedy would eventually get him there, too, his mother warning Andy whenever he talked about moving to New York that he would wind up “dead in a gutter” (Bockris 77).

Assuming Andy actually read “Paul’s Case,” his severe depiction of the story’s conclusion was much more than a stunt, was likely a response to the unsettling biographical similarities between him and Paul. That’s only if he actually read the story. It is entirely likely, however, that Warhol never read “Paul’s Case,” that another student told him what happened at the story’s end and Andy went from there. Much like Warhol’s overall intelligence—Gore Vidal allegedly once said Warhol was “the only genius with an I.Q. of 60”—Andy’s reading habits are highly disputed. Bockris claims Warhol “read voraciously,” yet is quick to add that the artist paid “particular attention to the photographs” (57). In his biography of Warhol, Wayne Koestenbaum contends Warhol was an undiagnosed dyslexic—the children of working-class immigrants were not often diagnosed with dyslexia in Depression-era America—because what little of his actual handwriting survives is full of transpositions like “scrpit” for “script,” and “herion” for “heroin.” While Warhol did write numerous books, which suggests high literacy, they were all transcribed from recordings.[8] Warhol, in fact, used ghostwriters at least since his Carnegie Tech days when Andy and his friends Ellie Simon and Gretchen Schmertz would “get together after class and ask [Warhol] what he thought about the book or play in question. Gretchen would put his thoughts, which she remembered as always interesting, into literary English, then the three of them would go over the paper to make sure it sounded as if Andy had written it” (Bockris 61). Despite their best efforts, Warhol failed out of Carnegie Tech his freshman year because he was unable to pass a writing-intensive course called “Thought and Expression”—he was readmitted after passing the course when it was taught by a more forgiving professor over the summer. And while the written word, always in the same spritely and angular script, features prominently in Warhol’s art, particularly his earlier commercial works, that distinctive handwriting was actually his mother’s, whom he routinely got to help him with any illustration that required words—when his mother wasn’t up for it, Warhol’s longtime assistant Nathan Gluck could ably forge Warhol’s mother’s handwriting.[9]

Yet Andy did have a college degree, and he did graduate fifty-first in a class of 278 at Schenley High School. The art critic Blake Gopnik’s forthcoming biography of Warhol emphasizes the artist’s deep and wide reading habits and their effect on his work. Warhol was certainly capable of reading—he had a special fondness for “Page Six” of the New York Post—so it makes sense that he would have read “Paul’s Case” when it was assigned. And, assuming he did, he does cut to the core of the story with his severe depiction of Paul’s demise. Fatalist Andy, who followed up his Campbell’s Soup paintings with the Death and Disaster series, who made a walking corpse of himself with his white wig and pale skin, distilled “Paul’s Case” to its essence: death. Andy was obsessed with death, devoting an entire chapter to the subject in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, albeit a chapter of only two sentences: “I don’t believe in it, because you’re not around to know that it’s happened. I can’t say anything about it because I’m not prepared for it” (123). In Andy’s estimation, death was meaningless, as meaningless as a smear of red paint.[10]

The ambiguity surrounding Andy Warhol’s reading habits reflects a larger ambiguity that accompanies all assessments of his life and work: despite being the embodiment of fame and as “overexposed” as a person can be, little can be said definitively about him. Warhol believed everything, even the stuff that contradicted. When asked if Pop Art criticized capitalism, he said it did. When asked if Pop Art celebrated capitalism, he said it did. In interviews, he agreed with whatever the interviewer said; in one famous instance, Warhol said it would be much easier if his interviewer simply told him what to say so he could repeat it back verbatim. Moreover, not only did Warhol say everything, he recorded and catalogued all of it. He composed three memoirs during his lifetime and tape-recorded almost all of his interactions. His diaries, which he started keeping at the suggestion of his accountant following an irs audit, maintain a record of everything he bought, everyone he met and everything he did over the last decade of his life. His grandest project, the Time Capsules project, even preserved the detritus of his life. Starting sometime around 1974, Warhol began to collect the miscellany of his existence—personal correspondence, magazines, source materials, ticket stubs, partially eaten food and whatever else landed on his desk—in cardboard boxes. When he died, Warhol left behind roughly six hundred of these boxes, each an intimate and disjointed chronicle of the day-today goings-on of an artist and his community. Now housed in the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the Time Capsules have only recently attracted serious critical attention, largely because so few knew what Warhol had been up to. Add it all up and it becomes clear that due to his profligate signification, there is an effectively limitless amount of information available about Andy Warhol, information that can be arranged in whatever way the consumer prefers.

Contrast this with Cather, a fiercely private individual who was always circumspect in the execution of her public self, evidenced, obviously, by the exacting demands regarding the posthumous life of her words and the prohibition on publication of her letters. She offered a precisely calibrated “Catherness” in interviews, always keeping her identification with things, the West for instance, a little bit incomplete—when asked in 1921 about the inspiration Nebraska gave her, Cather told the Lincoln Journal Star, “Everywhere is a storehouse of literary material. If a true artist was born in a pigpen and raised in a sty, he would still find plenty of inspiration for his work” (Hinman 46). Nonetheless, like Warhol, Cather wanted to be known and was not afraid to court attention—shrinking violets, as a rule, do not wear such fabulous hats—a situation Brent Bohlke summed up wonderfully: “Willa Cather courted and enjoyed public notice, yet she loved anonymity and seclusion. She was enamored of the notice of the press and deeply resentful of the intrusions the press made upon her time and energies. She sought fame but disliked attention” (xxi).

Perhaps if Cather had adopted a cartoonish persona and worn a fright wig, she, too, could have achieved the difficult mix of fame and anonymity that Warhol managed. After all, the challenge of postmodernity—and Warhol, regardless of his IQ, understood post-modernity better than most—is not too little meaning: it is too damn much meaning. Consequently, as the eras have changed, Cather’s strategy of keeping information about herself to a minimum only makes the clues she did leave behind more valuable and profound. Warhol, on the other hand, could have provided a skeleton key to unlock his entire being—a violent red smear of paint in response to a morbid story that felt far too autobiographical, perhaps—only to have it lost forever in the debris of his semiotic promiscuity. More than anything else, this is what I have learned from the infrathin kinship of these vastly different figures: a puzzle can confound by providing too few pieces, or too many.