From Cather Studies Volume 13

Growing Pains: The City Behind Cather's Pittsburgh Classroom

As a small-town, midwestern girl of twenty-two settling into the foreign environs of the rapidly developing Pittsburgh of 1896, Willa Cather was understandably homesick. She was, though, equally entranced and excited by the energies and cultural opportunities that lay before her in the bustling industrial complex known as “Steel Town.” Within five years of arriving, she entered the classrooms of that city, and her experiences there have been recounted as completely as possible, based on available sources. But, as all teachers know, teaching experiences are shaped by far more than just the students in the classroom and textbooks from which they learn.

In 1901, when Cather began teaching, Pittsburgh was a changing tableau, suffering from adolescent growing pains of trying to determine its direction and identity. Thick with the noise of industry, the city projected a vibrancy and energy that bespoke its shifting face as immigrants poured in, wealthy capitalists contributed to civic improvements and public works, and concerned citizens agitated for beautification of the cityscape. Education was a priority for its civic leaders and captains of industry and for the ordinary workers who sought the American dream for their children. During the five years in which Cather was a part of Pittsburgh’s educational system (1901–6) significant changes took place in the city’s schools, changes propelled by shifting cultural demographics and by the demands of a city trying to establish itself as a leading commercial and cultural center. Not unlike the city itself, Cather, as a beginning teacher, was experiencing growing pains and learning about a world beyond the plains of Nebraska. The pulse of the city was that of the teenagers whom she taught, beating with energy, excitement, and hopeful expectations—with just a shadow of fear. Cather’s response to these sometimes painful changes is reflected in two of her stories written during her teaching years, “The Professor’s Commencement” and “Paul’s Case.” These works not only reveal her concerns about the changes in education at the time, with commercial studies displacing the liberal arts, but also show the troubling effects on her students of rapid cultural change and a consequent shift in values.

Hired in March of 1901 to teach at Central High School, the academic curriculum–based school of the city, Cather was immersed in this rapid change. Between 1902 and 1908, the population of Greater Pittsburgh swelled from about 950,000 to 2.2 million (Nevin 8–9; White 31). In 1902 manufacturers were handling ten million tons of cargo and producing 450 million dollars annually in revenue (Nevin 8–9). “The millionaire springs up in Pittsburgh like a weed,” one commentator wrote, and an estimated 250 millionaires called the city home (Nevin 42, 46).

But Pittsburghers were not all of the moneyed class. Carnegie alone employed about forty thousand workers, with Westinghouse hiring ten thousand more (Nevin 34, 38). Whereas the early entrepreneurs and settlers of the area who had built this wealth had come largely from Germany and the British Isles, this new crop of workers were “colored and foreign” (Nevin 53), with the largest number from eastern and southeastern Europe. While Cather, who had known and admired the Bohemians back home in Nebraska, would, no doubt, have been delighted to see some students from this latter ethnic group in her classes, that was not to be the case. The high schools of the city had been divided by areas of study, with Central High School, Cather’s first education employer, hosting the classic, academic program. By the time Cather began work at Central, three high schools existed in the city. The Commercial Department left Central High School in 1896 for its own building on Fifth Avenue, where for some time the Normal School was also housed. During the 1890s over a thousand teenagers from the families of manual workers entered the Commercial Department of Pittsburgh’s public high schools (DeVault 7). Their largely unskilled working parents sought for their children an education that would propel the young people into jobs beyond the manual trades. They and their families recognized that an academic program that included studying works in English literature, Latin, and ancient history placed their children at a disadvantage in the job market, leaving them with no specific job skills. Meanwhile, the Commercial School boomed. Records show that in 1901, the year in which Cather first taught, sixty-eight graduated from Central High School, while fifty-three matriculated at the Normal School and eighty-nine at the Commercial High School (Fleming 223).

The students in Cather’s Central High classrooms were not the sons and daughters of the barons of industry, most of whom by the 1890s were attending prestigious preparatory schools elsewhere (Couvares 100). Nor were they part of the most recent wave of immigrants; rather, they were the children of established, skilled workers who had carved out a place of rising social prominence for themselves as “native” Pittsburghers, having their roots in the first wave of British and German immigration. A glance at her class lists reveals names like Lovelace, Forester, Hutchinson, Kelly, Miller, Soffel, Otte, Klingensmith, Merker (Kvasnicka 160, 162). Conspicuously absent from these rolls are eastern European surnames, or even Italian. The Italian residents of Pittsburgh had become, next to the Germans,“the largest and the most prosperous foreign element” of the city, numbering over forty thousand in the Greater Pittsburgh area (Nevin 57). Although the district known as “Little Italy” was not far from Central High School (Nevin 58), Italian youth generally did not attend the public school but attended parochial schools, perhaps not feeling welcomed at Central High, which was in 1871 said to be “one of the finest, if not the finest [high school] in the state” (qtd. in Kristufek 21). By the time of Cather’s arrival, however, Central had lost some of its prestige as the school for children of the rising middle classes. Early on, Central had, after some contentious struggle, integrated, and in 1872 listed three African Americans among its students (Morris). As it continued to grow more diverse, greater pressure came to change its educational mission.

Until 1909, though, the schools continued to be governed under the ward system, limiting the ethnic makeup of the students because of their place of residence. Even labor policies, Francis Couvares writes,“encouraged this ‘Balkanization’ of the population” with ethnic communities lying primarily between the river and the railroad. “Beyond the tracks,” Couvares continues,“steep bluffs sharply marked off the zone of settlement” (89). In “The Professor’s Commencement,” Cather pointedly refers to these bluffs on Mount Washington, a geologic and social line of demarcation: To the west, across the river, rose the steep bluffs, faintly etched through the brown smoke, rising five hundred feet, almost as sheer as a precipice, traversed by cranes and inclines and checkered by winding yellow paths like sheep trails which led to the wretched habitations clinging to the face of the cliff, the lairs of the vicious and the poor, miserable rodents of civilization. (484) Cather recognized that geography was a sociological demographic and that the students beneath the bluffs were like the Cyclopean exiles of Ulysses’s adventure. Atop an opposite bluff that overlooked the clamoring Union Station sat Central High School. Professor Graves, in “The Professor’s Commencement,” describes the school as “a fortress set upon the dominant acclivity of that great manufacturing city” and commanding its heart (483). That world outside sometimes threatened learning as the “puffing of the engines in the switch yard at the foot of the hill” would drown out the voices of students as they recited (484).

This is not to say that Cather was fully dissatisfied with the place in which she taught or the quality and type of student whom she was teaching. The majority were from the now established and comfortable middle class. Their fathers were physicians, musicians, railroad conductors, and hotel managers (Kvasnicka 160). The high school prided itself in the academic achievements of its students and regularly published in local papers pictures and stories of its honor students. (See, for example, Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 21 March 1902). In such an atmosphere of success, one can imagine how the faculty would have reacted to a student like Paul in “Paul’s Case.” Paul’s flippant attitude and contempt for his teachers, if not for the entire education system, go undisguised. Kvasnicka notes that Cather recalled one young man, likely the model for Paul, who was the “only student she never could seem to reach” (165). Cather would have participated in faculty disciplinary hearings, perhaps even for her one unreachable student. Central High School was known to apply discipline policies rigidly, especially since a long history of student pranks was a tradition at the school (Morris). The almost inquisitorial atmosphere of Paul’s suspension hearing leaves his teachers “dissatisfied and unhappy; humiliated to have felt so vindictive toward a mere boy” (217). Cather’s empathetic tone points to her dichotomous view of the educational system, a view perhaps reflective of the city’s culture itself (Morris). Echoing Caesar’s Gallic Wars, she had written in a 10 January 1897 article for the Nebraska State Journal, “Now all Pittsburgh is divided into two parts. Presbyteria and Bohemia, the former is much the larger and more influential kingdom of the two” (“Presbyteria and Bohemia” 505). At Central, Cather taught students from both kingdoms. While the number of Bohemian Pauls was likely smaller than the sons and daughters of Presbyteria, perhaps they better matched her own sentiments. She was enthusiastic about her profession, though, commenting to the astonishment of interviewers that she taught Latin because she liked it (Bloom 103). Teaching,she said,“suited her” (Robinson 106). Cather was known to have invited favorite students to her lodgings on Sunday afternoons for tea, and they recalled the warmth with which she entertained them. They recognized and appreciated her interest in them as an endorsement of their potential both as scholars and as young people of social refinement.

Still, we know that she had an interest in those “other” students in her classes and those who made up the classes in competing high schools. Cather realized that the city’s schools were not serving just students of the established middle class. In an 8 December 1901 column for the Pittsburgh Gazette, Cather described her experiences on Mulberry Street, an ethnically diverse area of the city where she did research for her column. There she observed the contrasting lives of Italians, Germans, Hebrews, and African Americans (“Pittsburgh’s Mulberry Street” 871). Between 1901 and 1902, Cather also wrote for the Gazette a series of “investigative reports” on the city’s ethnic communities, including Pittsburgh’s Chinatown (Zhu and Bintrim 4). As a champion of immigrants she had known in Nebraska, how chagrined she must have been to have read the 1905 thirty-seventh annual report of the Pittsburgh Board of Education, indicating that the board was turning attention to the “education of the masses” and considered their teaching staff a “great standing army of peace, maintained to fight foreignism, illiteracy, and vice” (qtd. in DeVault 39). The fight against illiteracy Cather would have embraced, but she would not have seen herself as a teacher-soldier fighting against “foreignism” and its compatriot “vice.” At the time, the term “foreignism” connoted fear of recent working-class immigrants who chose not to assimilate or to embrace Americanism in language and religion but to retain their cultural identity and customs. Such “foreigners” were often cited in the press as involved in corruption and criminal activities, as well.

As a result, Pittsburgh schools were undergoing growing pains, grasping at ways to deal with the city’s burgeoning diversity while trying desperately to provide workers to feed the maw of their industrial complex. Truancy was a problem, something Cather recounts in “Paul’s Case.” In 1895 a state law made public school attendance compulsory for ages eight to thirteen, yet only five years later, although attendance levels were steadily rising, Pittsburgh still had “one of the lowest high school attendance rates of large U.S. cities” (Kleinberg 125, 131). Paul is a product of the rising middle class that, while sending its children to high school, often in the rigorous academic program, valued money-making over the liberal and fine arts.

In response to these crises and other problems, the Pittsburgh School Board took action. In 1904 the teachers launched a petition campaigning for higher wages, merit pay increases, and retirement programs. Whether or not Cather signed those petitions is unknown. The school board, however, responded to the teachers’ concerns by establishing a Teachers’ Salary Commission, raising yearly salaries, setting up a class system based on experience and training, and putting in place a graduated salary scale (Greenwald 42–43). These reforms would have been welcome news to women teachers like Cather whose wages had been “tailored to meet the needs of single women, not career-minded professionals” (Greenwald 42). Salary levels for women teachers had been depressed as the number of women attending normal schools increased and as the number of graduates exceeded the number of available entry-level teaching positions. This situation led to “higher unemployment rates for teachers than of other women workers at the turn of the century” (Kleinberg 153).

The school board also faced the perpetual problem of money management. Charles Reisfar, father of a Central High student in Cather’s classes and secretary of the board, presented the financial case for the high schools on February 1, 1902. Asking for a $861,280 outlay of monies, Reisfar earmarked $700,000 for teachers’ salaries, $3,000 for repairs to the high school’s physical plant, $1,000 for fuel, $2,500 for janitor services, $100 for the library, $2,300 for furniture, $600 for books, and $1,000 for high school athletics (Municipal Record 402). Reflecting social interests of the day, athletics was now a budgeted line item. The popular annual exposition in Exposition Park is evidence of those interests. What had once been an event to draw the huge working class had, by 1890, “become an event of ‘high culture,’” denying its original purpose of providing “popular” (i.e., for the people) entertainment and instead appealing to the “aspiring bourgeois spirit” of the rising middle class (Couvares 101). By the turn of the century, sport therefore became central to reinvigorating the exposition’s original purpose. Sports clubs sprouted up throughout the city in “revolt against bourgeois gentility and Protestant repression” (Couvares 102), the latter of which Cather commented on critically, but amusedly, during her stay at the Axtells’ home (see her letter to Ellen Gere of 29 June 1896).[1]

For the rising middle class of Pittsburgh, Sunday afternoons were often their sole opportunity to encounter the arts or to engage in sport. Sport, like music, offered relief from the humdrum work place, and boys and girls alike were strongly encouraged to “exert themselves physically.” All this led to a trend toward “middle-class sport” (Couvares 102–3), something the schools were forced to acknowledge and embrace. In 1880 team sports flourished at Central High School, including football, baseball, hockey, and girls’ basketball. By 1889 the school had “standardized cheers, colors, mottoes, and insignia” (Couvares 103). One can imagine Cather being pleased with this organized display of physical vigor at the school. After all, she had pumped hand cars, ridden horses, and raced Pittsburgh street cars on her bicycle (Selected Letters 39). Her interest in sport even appears in an early story, “The Fear That Walks by Noonday,” published in the University of Nebraska Sombrero in 1895. Not only did Cather attend university games, but she also knew something about football, naming positions and play strategies. She recognized the energy of youth, whether on the playing fields of Lincoln or in the vigorous environs of Pittsburgh and knew that such energy demanded an outlet. Pittsburgh had growing pains and was,like Chicago, “proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning. / . . . Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of / Youth” (Sandburg 3–4).

Cather’s students, male students in particular, were caught up in this cultural emphasis on hale and hearty physical activity and were attuned to the Teddy Roosevelt Rough Rider mentality that was sweeping the nation. For her teenage readers, the American Boy magazine was the gospel, something of which Cather, as a budding journalist, must have been aware. Just as athletic clubs began springing up throughout the Pittsburgh area, so did American Boy Clubs draw the preteens and teens. Like nearly every major city and small town in America, Pittsburgh sported a number of clubs of the “Great American Boy Army,” groups devoted to developing “manliness in muscle, mind and morals” (“Great American” 120–21). The May 1903 issue sported a Young Rough Rider on its cover and included a photo of the Pittsburgh “Rough Riders,” a troop of boys ages eight to twelve, wearing full western regalia and on horseback (“Pittsburg ‘Rough’” 219). This spirit of sport, play, athleticism, and daring was a strong attraction for Cather’s students. When Cather created her protagonist in “Paul’s Case,” though, she drew a portrait of a teenager who was an antithesis to this cultural norm. Paul is a misfit among his peers; he is drawn to the theater, not the playing field. Music, not touchdowns, fires his imagination. He stands apart from the prototype of the American Boy.

The magazine also reflected the values that shaped the shift in education from classical to so-called practical learning. Each issue profiled the boyhood of a successful man such as Rockefeller, Carnegie, Heinz, or Chicago meatpacker Armour. Often quoting their advice, even if posthumously, the magazine offered models of success who told youth that “this is the country of the young. We can’t help the past, but we can look out for the future” (“Sayings” 224). Carnegie is lauded for his “good penmanship” and “knowledge of arithmetic” that “gave him a chance to secure a clerical position, and this was given up that he might learn telegraphy” (Harbour 211). Articles stressed that a boy should seek work in railroading, engineering, telegraphy, electricity, bookkeeping, printing, or drafting. Regular monthly columns were titled “Boys as Money Makers, Money Savers,” “Boys in Games and Sport,” and “The Boy Photographer.” America was on the move, away from traditional courses of learning and toward reading and study that would make businessmen and athletes of the younger generation. In such a climate, most of Cather’s students would prefer to become an Alexander Bartley, successful engineer even if failed man, to being Horatius at the Bridge. In “Paul’s Case,” Cather describes the neighborhood fathers who embrace this gospel of progress and recount to one another “legends of the iron kings [punctuated] with remarks about their sons’ progress at school, their grades in arithmetic, and the amounts they had saved in their toy banks” (227). While Paul “rather like[s] to hear these legends . . . that were told and retold on Sundays and holidays,” he has no interest in struggling through the “cash-boy stage” to reach the pinnacle of success in business (229).

In 1905, Cather’s last year of teaching, the American Boy had garnered its place in the national consciousness, along with all the accompanying values of hard work, physical hardiness, and inventive genius. The American boy was destined to become a Tom Edison, Andrew Carnegie, Cy Young, or Richard Byrd. Little if any mention is made in any issue of the American Boy at this time of finishing school so as to become a liberally educated man. Rather, the goal of getting an education was to become a respected businessman and subsequently to become wealthy enough to embrace Carnegie’s directive to share with others the “sacred trust” of one’s wealth. Paul’s defiant attitude in school results in his being “taken out of school and put to work” (235), the accepted solution to setting him on the right path to becoming like the young man whom his father held up as a model—a previously slightly “dissipated” youth who was now a “clerk to one of the magnates of a great steel corporation” (228).

Cather would later attack these changes in education through the words of Professor Godfrey St. Peter in The Professor’s House. He is dismayed at the commercialization of education and is exhausted by the “old fight to keep up the standard of scholarship, to prevent the younger professors . . . from farming the whole institution out to athletics, and to the agricultural and commercial schools favoured and fostered by the State Legislature” (58). Professor St. Peter comments to his younger colleague Professor Langtry that “there have been many changes” at the college in recent years, “and not all of them are good” (54). The incredulous Langtry can’t grasp what the Professor means when saying that the current crop of students is different from those of earlier years, a more “common sort” (54). This shift occurred in Central High’s and later Allegheny High’s population, as well. While supportive of the city’s effort to offer educational opportunities to the working class, and particularly to immigrant families, Cather knew the Commercial High School on Fifth Avenue competed with her own, attracting capable young minds to the god of Mammon rather than to Apollo and the Muses. In “The Professor’s Commencement” Professor Graves, an early sketch of Professor St. Peter, knows what Cather knows. She saw the lure of Mammon pulling especially immigrant youth from the liberal arts that would free them, that would, as the Professor says, “secure [for them] the rights of youth; the right to be generous, to dream, to enjoy” (“Professor’s Commencement” 484). “They were boys and girls from the factories and offices, destined to return thither, and hypnotized by the glitter of yellow metal”; they were “practical, provident, unimaginative, and mercenary at sixteen” (484). He hopes and believes that he has over the years given to at least some of his students “a vital element that their environment failed to give them.” But, the Professor admits, “[T]his city is a disputed strategic point. . . . It controls a vast manufacturing region given over to sordid and materialistic ideals. . . . I suppose we shall win in the end, but the reign of Mammon has been long and oppressive” (483).

The flood of students to the Commercial Department of the Pittsburgh high schools also resulted in a decline of program quality during Cather’s tenure. Students who failed the entrance exams were often admitted simply to meet the demand of filling office jobs in the city (DeVault 33). By 1903, the ten skyscrapers in the city skyline (DeVault 144) were full of bookkeepers, typists, and stenographers. Fourth Avenue was called “the Wall Street of Pittsburgh,” and there were in 1905 more typewriters in Pittsburgh than in any other American city, except New York (DeVault 144, 1). One instantly recalls the picture of Cather herself hunched over her typewriter as she worked, sometimes feverishly, to meet deadlines for columns in the Pittsburgh Leader or The Home Monthly.

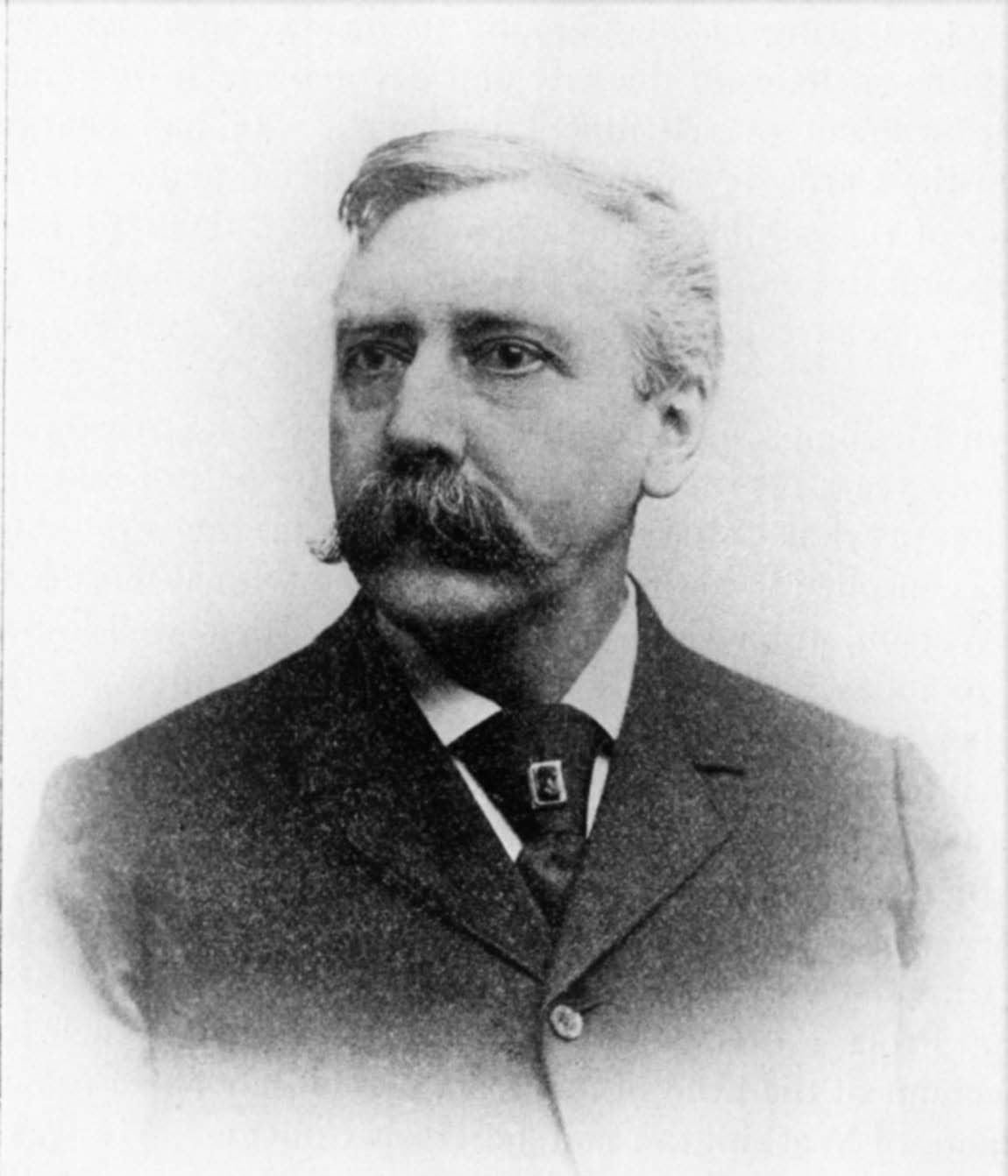

Both Cather and some of her colleagues were caught in this transition from classical education, as that which distinguished the learned and professional class from the working class, to commercial education, as the only course for success in turn-of-the-century America. Professor Frederick Merrick was one such colleague.[2] He was a legend when Cather arrived at Central High School in the spring of 1901. Hired first in 1871 to teach Latin, Professor Merrick eventually chaired the Math Department and served thirty years before resigning in December of 1900. Cather likely replaced him, at least with part of her teaching load, notably the course in algebra, which was a trial for her.

Fig. 4.1. Prof. Frederick Merrick, from My High School Days by George Thornton Fleming, Press of

William G. Johnston, 1904.

Fig. 4.1. Prof. Frederick Merrick, from My High School Days by George Thornton Fleming, Press of

William G. Johnston, 1904.

Professor Emerson Graves, as Cather describes him in “The Professor’s Commencement,” embodies many of the characteristics of the beloved Professor Frederick Merrick, to whom the Class of 1880 paid tribute in their twenty-fifth reunion class book. Like Professor Graves, who feels “distraught and weary” (“Professor’s Commencement” 482), the aging Professor Merrick resigned “on account of the need of rest from mental labors” (Fleming 205). He is remembered as a “courtly professor—ever gentlemanly and kind” (Fleming 207), a “very dignified man of fine fibre” (Bingham 17). His photograph shows a silver-haired man with kind and expressive eyes, not unlike his literary counterpart whose slight build and silver-white hair made him memorable to this students “long after they had forgotten the things he endeavored to teach them” (“Professor’s Commencement” 481). As Professor Graves looks back on his teaching career so similar to Professor Merrick’s, he uses the language of battle to describe the struggle he has undergone for the sake of the young people in his classroom. On his last morning at the school he feels the call of duty as he has never before felt it, on the very day “he was to lay down his arms” (484). At his farewell dinner he sees his colleagues not as just old men but as “spent warriors” (487), and he ironically stumbles once more in an effort to recite the story of “Horatius at the Bridge.”

While Cather could not have read the Class of 1880 reunion book from 1905 prior to writing “The Professor’s Commencement” (published 1902), included in that class book is an open letter from the retired Professor Merrick. In response to his students’ inquiries, he, in words akin to Professor Graves’s, responds that he had fought the good fight. He says that he is flattered by their praises but is conscious of “the weak and trembling battle that I have sometimes, as the boys say, put up” (Bingham 97). Like Cather’s Professor Graves, Merrick labored “in the garden of youth” for “motives Quixotic to an absurdity” (“Professor’s Commencement” 483, 482).

Cather likely did not know Professor Merrick personally since after retiring he removed to his hometown in Massachusetts. His reputation, though, remained, and some of his former students still attended Central and likely were in Cather’s classes. Many of his former colleagues were also still on staff. How much of Merrick appears in Cather’s portrait of the Professor in “The Professor’s Commencement” is arguable, but the Professor’s case presents a sense of what surrounded Cather as she held her first teaching position. She experienced education shifting toward acquiring “mechanical skills and the making of money” rather than “to an examination of moral values and the traditional liberal arts” (Bloom 102). She viewed education as “the last refuge of traditional values” and felt that “in the secondary schools attention to the classics was probably even more perfunctory” than in the universities (103).

Cather was apparently not alone in worrying about the loss of traditional areas of study and culture for both the youth and the residents of her adopted home. This was a major growing pain for the city itself: How could it provide more than just jobs and money for its people? From where would exposure to the arts come? How could Pittsburgh compete with Eastern Seaboard cities in culture, music, and the arts? Pittsburgh already had more money. In the lingo of the day, the oft-used phrase “He’s a ‘Pittsburgh man’” evoked at once an image of wealth and power (DeVault 168). The captains of industry, though, were not the only ones who worried. Cather found herself surrounded by civic-minded women of Pittsburgh whose goal was to address these questions and to promote civic and sociological advancement “in every possible way” (Civic Club iv).

Groups like the Civic Club of Allegheny County (ccac) committed themselves to “moral environmentalism” as well as to “urban progressivism” (Bauman and Spratt 153). Moral uplift of the rapidly changing, cosmopolitan city was sorely needed, and the women envisioned themselves as the ones to do it. The Education Department of this group “led a move to open several school playgrounds for the public use,” including one at Central High School (Bauman and Spratt 177); they established recreational parks throughout the city, and in conjunction with the Central School Board built public libraries, gyms, baths, and game rooms. The Civic Club “open[ed] the school yards as playgrounds” and provided swings and sandboxes; they employed teachers to direct games, conduct story time, and watch over free play. The Civic Club also initiated reform policies for everything from child labor laws and juvenile courts to pure water and smoke ordinances. But the arts were not a major player in their agenda, and not all their projects achieved the hoped-for success. Both playground workers and librarians “paid little more than ‘lip service’” (Couvares 115) to the goal of moral uplift. Many librarians did “little more than read stories and fairy tales to children,” turning the libraries themselves into “pleasant place[s] staffed by pleasant people into whose hands children could be safely deposited for a few hours on weekends” (Couvares 115). Cather, who as a girl had entertained her younger siblings with fanciful stories, knew that stories alone would not launch children into a lifelong love of learning and literary appreciation.

Three amusement parks built between 1900 and 1910 (Couvares 222), dance halls, skating rinks, and public parks all proved more enticing to youth than did playgrounds and libraries. Theaters, including at least one that featured a local acting troupe, were sprouting up throughout the city and were equally alluring, as Cather knew and described in “Paul’s Case.” In his position as an usher at Carnegie Hall, Paul becomes “vivacious and animated” (219), a far cry from his cynical and flippant schoolboy self: The “first sigh of the instruments seemed to free some hilarious and potent spirit within him. . . . He felt a sudden zest of life” (220). The “delicious excitement” that comes to him in the concert hall is, he muses, “the only thing that could be called living at all” (221). In what Cather describes as the twelve-story Schenley Hotel, looming across the street, he imagines a life of ease and exotic beauty, and the stage entrance becomes for him “the actual portal of Romance” (232). After being backstage, he finds “the school-room more than ever repulsive” (233). The trivial question in his Latin class of prepositions that govern the dative is meaningless to him. Many of Cather’s students came from homes like Paul’s on other Cordelia Streets and longed for escape into a world of romance and beauty, something theater could offer them, even if temporarily. But local theater companies were being sorely taxed by their competition. By the late 1880s “impressive touring shows of the New York and Philadelphia syndicates” had smothered local stock companies as the rising middle class demanded more spectacle and glamor (Couvares 121). Bourgeois patrons “demanded more exclusive fare,” while “poor alien audiences, unfamiliar with the conventions of theatrical comedy and melodrama” (Couvares 121), preferred the comedy of vaudeville. Paul was of the first class, lured by the splendor of professional touring troupes and befriending stock company players like Charley Edwards. The less cultured gravitated to the burlesque and variety shows springing up throughout the city.

Both these forms of entertainment, however, were under threat. In 1905 John Harris, proprietor of highly successful ten-cent houses in Pittsburgh, built the “first all-motion picture theater” in America (Couvares 122). But the moving picture had by then already made its presence known in the city. As early as 1896, the year that Cather arrived in Pittsburgh, theaters like the Bijou, as well as smaller venues, were experimenting with showing cinematic clips, using either Edison’s “Marvelous Vitascope” or the French Cinèmatographe (Aronson 28). By the time Cather left Pittsburgh in 1906, forty-five, full-fledged “nickel theaters were paying for annual city operating licenses” (212). While the allure of the moving picture may not have yet been widespread among her students, fascination with the movies had begun. Costing only a nickel, this new form of entertainment offered equitable access to youth of all classes, and even reformers of the day, concerned about the moral and cultural impact of this new phenomenon, generally considered the movies “less socially problematic” than the saloon and pool halls that lined areas like the Strip District (Aronson 13).

For teenagers in her classrooms, the imminent arrival of the nickelodeon was, no doubt, like that of the iPhone for today’s youth. But for sensitive culturalists like Paul, the movies signaled the death of all that was marvelous about live theater. Nonetheless, the Saturday evening picture show provided escape and consolation, a place to glimpse a side of life that many young people felt had been denied them (Couvares 122). In her 1929 letter to Harvey Newbranch, a friend since her university days and editor of the Omaha World Herald, Cather lauded the “old traveling companies” who put on “creditable performance[s],” and she expressed regret that that they had come to an end (Willa Cather in Person 185). She concedes, though, that the “screen drama [has] a great deal to be said in its favor” but is a very different thing from a play (186). She concludes that movies are “a fine kind of ‘entertainment’ and are an ideal diversion for the tired business man” but that only “real people speaking the lines can give us that feeling of living along with them” (187). The movies were, however, here to stay, and the students in Cather’s classes had embarked upon a new way of learning about the world, one devoid, perhaps, of deep emotions and the firing of the imagination that mark us as human.

Like the movies, the three amusement parks of the city continued to attract large audiences, particularly young people and working-class crowds. When Dream City, “the larger of the two East End parks, opened on Memorial Day, 1906,” thirty-seven thousand people poured in (Couvares 122). But, neither the cinema nor the parks were venues for the arts. Whereas Pittsburgh had long boasted museums where students could expand their appreciation of fine art, it would take Carnegie himself to put Pittsburgh on the map as a center of the arts equal to the larger, Eastern Seaboard cities. Embracing an Arnoldian “Gospel of Art,” Carnegie established his International Exhibitions in 1895, encouraging artists to display their works in Pittsburgh in competition with one another and promoting a national American art (Neal 9, 14). His was an experiment in “cultural uplift” with hopes of “spiritualiz[ing] the local populace” (Neal 14). Concerned that the young people had little access to great art, Carnegie organized and encouraged visits by secondary school classes, and within one year of the institute’s opening,“such field trips were common and there were even visits from public schools in which art formed no special part of the curriculum” (Neal 47–48). A survey of curricular offerings at Central High School shows, though, that freshmen in the academic course were required to take drawing (Fleming 219). Paul of “Paul’s Case” is one such student. Cather recounts his drawing master’s frustration over this boy whom he could neither understand nor reach. Paul dozes at his drawing board, and his art teacher’s despair is evident in the declaration that “there is something wrong about the fellow” (217). Not all students could be reached by the opportunity to engage in the arts, as Cather well knew. Problem students did exist, and a teacher’s life—whether Cather’s, Paul’s instructor’s, or Professor Graves’s—was sometimes rife with disappointments. The city, however, was ready and eager to prove itself a place of culture and refinement. Coupled with a thriving venue of concert halls and professional musicians, Pittsburgh came into its own as a city that knew and loved the arts, and not just the smell of money. As Joseph Murphy points out, “Carnegie’s concert hall, museum, and library in Pittsburgh’s Oakland section” became an “important refuge for Cather on the ground as for her protagonist in ‘Paul’s Case’” (6).

In this atmosphere of a city struggling to find itself, Cather began her teaching career. We are a part of all that we have met, the Professor remarks in “The Professor’s Commencement,” alluding to a line from Tennyson’s “Ulysses” (481). Like the Professor, Cather persisted in teaching the classics to her students and insisted on their importance in shaping a liberally educated person. As late as 1939, in a letter to the editor of the College English Association, Cather noted that unless American boys “read the great English classics in high school and in college, they never find time to read them” (Willa Cather in Person 190–91). She then asserts, “I think we should all, in our school days, be given a chance at [the classics]” (191). Like her students, though, she found herself strolling in the parks of a vibrant city, seeing beyond the smoke and clamor, preparing herself for a world much different from that of her parents. In her Pittsburgh teaching years, Cather observed the effects on her students of rapid social and cultural changes and the corresponding effect on public education itself. But she, like Pittsburgh, forged ahead. She would continue in her later works, like My Ántonia, to embrace otherness and diversity, to defend classical education through the voice of Professor Godfrey St. Peter, to criticize rampant materialism in One of Ours and A Lost Lady, and to champion the arts in works like The Song of the Lark and “Uncle Valentine” (1925). The direction for Cather’s body of fiction was thus shaped, in part, by both her early experiences in a city where change proved inevitable and by her time in a classroom, the training ground not only for her students but also for herself.