From Cather Studies Volume 14

Unsettling Accompaniment: Disability as Critique of Aesthetic Power in Willa Cather's Lucy Gayheart

In “Willa Cather and the Performing Arts,” Janis Stout defines Cather’s concept of aesthetic power in terms of ability and strength. According to Stout, the power of an artistic performance for Cather consisted of an “artist’s enormous personal vigor, his intense investment in his art” (113), and “a force or intensity ... which engaged her response and lifted her out of herself into another dimension of reality” (107). The “transformation of life” at the center of Cather’s aesthetics, Stout argues, derives from her representation of artists as forcibly compelling, as able to hoist audiences above their disappointments and propel them toward transcendent beauty (113). More recently, Susan Meyer has echoed Stout’s argument while extending it further to argue that Cather’s “adulation of the vitality of the artist has an amoral quality” (98). In her article on The Song of the Lark, Meyer argues that protagonist Thea Kronborg repeatedly encounters threats to her body’s strength in the form of “shadowy bodies, ill bodies, unfortunate bodies, dying bodies,” and that the novel cruelly celebrates Thea’s unlikely triumph of her own robustness while revealing her “bodily precariousness,” her vulnerability to the “dark undercurrent” of illness, weakness, and disability that modernity’s conditions pose (112). Meyer concludes that Cather’s fiction regularly privileges aesthetics over ethics in a way that is “at odds with familiar moral standards, at odds with self-denial and sympathy with the weak and suffering” (111).

The strong aesthetic ascribed to Cather in these readings carries serious implications for the signification of less powerful characters in her texts, those “shadowy bodies” that Meyer mentions. In particular, it immediately complicates the presence of artists with disabilities in Cather’s texts, characters who are surprisingly numerous. In The Song of the Lark there is the concert pianist Andor Harsanyi, who has a glass eye, and in My Ántonia there are three performers with disabilities: Blind d’Arnault, the lame actress in Camille, and the singer Maria Vasak, who breaks her leg in the Alps.[1] When her performers themselves are not disabled, Cather also represents disability in accompanists and assistants: in “Paul’s Case,” Paul, whose teachers describe him as wrong-headed, strange, and “a bad case,” is the Carnegie theater usher and the unofficial dresser for the actor Charley Edwards (Youth 219); Miletus Poppas, who has chronic facial neuralgia, is the accompanist to Cressida Garnet in “The Diamond Mine”; and James Mockford, who limps from a bad hip, is the piano accompanist for Clement Sebastian in Lucy Gayheart. If what Meyer argues is true and Cather defines her aesthetics in opposition to illness and disability, then what are we to make of Cather’s interest in representing so many of her artists and accompanists as disabled?

Perhaps the perfect text for rethinking Cather’s aesthetic power is Lucy Gayheart, a novel that showcases not only an accompanist with a disability, James Mockford, but also a protagonist who is anything but robust. Slight in body and easily fatigued, Lucy also shuns powerful connections, identifying more easily with the immigrants and tramps in Chicago than with her hometown hero. Lucy is diminutive not only in body but also in stage presence, for unlike Thea Kronborg, she is not a diva but a lowly accompanist, a title denoting that she is at once necessary to the performance but also less significant. In his historical essay for the novel’s scholarly edition, David Porter has described Cather’s turn from Thea to the weaker Lucy as a pessimistic variation on the theme of artistic development, arguing that while The Song of the Lark delivers a fully formed artist, Lucy Gayheart aborts its artists and accompanists wholesale, representing a “darkening of [Cather’s] imaginative palette” in an “erosion of her vision of transcendent musical success” during her later years (277– 79). But Cather’s move from Thea to Lucy need not be pessimistic, for it may merely indicate her perspectival shift away from artistic formation and toward artistic production and accompaniment. Emphasizing the rift between ethics and aesthetics, accompanists draw attention to the offstage labors necessary for an aesthetic triumph like Thea’s, one that demands accompaniment to compensate for what is lacking in the artist’s performance.

Lucy Gayheart is a work that grapples with accompaniment as a theme at the heart of artistic production, and it does so distinctively through its representation of disability. Accordingly, it engages deeply with narrative prosthesis, what disability theorists David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder have described as art’s unappreciative reliance upon abnormal bodies. As Mitchell and Snyder have argued, characters with disability often symbolize narrative possibility; acting as points of departure, their alterity pulls stories out of the stasis of convention and into a “search for the strange”: “What calls stories into being, and what does disability have to do with this most basic preoccupation of narrative? Narrative prosthesis (or the dependency of literary narratives upon disability) forwards the notion that all narratives operate out of a desire to compensate for a limitation or to rein in excess. ... A narrative is inaugurated ‘by the search for the strange, which is presumed different from the place assigned it in the beginning by the discourse of the culture’ from which it originates” (53). In Lucy Gayheart the theme of prosthesis unfolds in a number of complex layers, beginning with the onstage appearance of the central narrative prosthesis, James Mockford. Through its strangeness, Mockford’s disability creates the opportunity for the narrative to occur at all, pulling Lucy from her humdrum experiences of teaching music in Haverford toward becoming a satellite in Sebastian’s artistic orbit. Mockford also brings narrative possibility to Sebastian, who gains years of success through the influence and support of his accompanist. Beyond plot, Mockford’s appearance onstage initiates the novel’s own search for the strange: limping across the stage as “a rag walking” (Cather, Lucy Gayheart 41), Mockford is a metonym for disability in narrative motion, a prosthesis made of print.

Despite its importance to narrative movement, however, Mockford’s role is complicated by his disability and his supposed unsuitability for the stage. Indeed, this combination of narrative significance and undesirability is a hallmark of narrative prosthesis. According to Mitchell and Snyder, although authors often need disability, as they rely on it to create meaning, they also demand that it be removed in order to cleanse the narrative; having performed the service of artistic prosthesis, characters with disabilities are then let go. Sebastian’s move to cut ties with Mockford in order to avoid giving him his rights fits well with how narrative prosthesis often works by relying on disability but then disposing of it once it has served its purpose. Understanding Mockford’s removal—both from Sebastian’s service and from the narrative—helps to make visible the deeper theme of prosthesis in the form of the novel’s multiple cruel reliances and breakups masquerading as friendships. Nearly all of the friendships in the book are defined by compensatory service and terminations: failing as props for his artistic career, Sebastian’s relationships repeatedly end when his friends disagree with him. Despite describing friends as beloved, Sebastian drops each of them whenever they begin to demand a relationship of more equivalence, one open to critique and disagreement. The same pattern of behavior holds true for Harry Gordon, who also employs his relationship with Lucy to compensate for the missing artistic pursuits in his life without endangering his reputation. Unable to abide threats to their power, both Sebastian and Harry abandon friendships whenever asked for more critical relationships. Cather thus portrays narrative prosthesis as both necessary and undesirable to both Sebastian and Harry, for both look to their accompanists to compensate for their inadequacies while also disdaining the presence of discord in their ventures.

Reading Lucy Gayheart through the theory of narrative prosthesis reveals how disability signifies imbalance in aesthetic compensation; however, it does not explain why this problem is so difficult to perceive. Lucy, our eyes and ears for most of the novel, never once suspects or doubts Sebastian, and even though she is an accompanist herself, she transfers her distrust entirely onto Mockford. Rivalries spring up everywhere in the plot, making it often difficult to know whose perspective to trust: besides the dispute center stage between Sebastian and his would-be “assisting artist,” the novel also takes us to a backstage consumed by infighting, where assistants are eyeing each other suspiciously as they vie for positions. To understand why Cather creates such an environment of mistrust, I turn to disability scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and her theory of the normate. Analyzing the confusion that occurs in encounters with disability, Garland-Thomson argues that the nondisabled react with disgust and fear as they scramble toward a haven of normalcy—what Garland-Thomson names the normate perspective. Garland-Thomson’s theory helps to explain multiple moments in Cather’s fiction, including Aaron Dunlap’s discomfort and fascination with Virginia Gilbert in “The Profile,” Thea Kronborg’s abhorrence of Mary the Hungarian maid, Jim Burden’s initial fear of Marek, and of course Lucy’s aversion toward Mockford. In addition to its explanation of these visceral responses, the normate concept also clarifies the themes of jealousy and competitive “insinuation” in this text, revealing that Lucy’s revulsion stems from her fear of losing her attachment to Sebastian and the norms he represents. Despite her confusion and prejudice, Lucy never realizes that her reading of Mockford is misguided; uncritically loyal to Sebastian, she cannot see that he is the one who is untrustworthy. Indeed, in Sebastian’s repeated action of gaslighting—of portraying his past relationships as broken and abnormal to his new prospects—he embodies the perspective of the normate, that which defines its own normalcy only by slandering the validity of the other. Pitting his new accompanists against the old, he convinces them to see themselves as normal against the mental and physical instabilities of his previous accompanists. As with his interest in his valet Giuseppe, Sebastian’s interest in Lucy Gayheart is in someone who will be eternally loyal without ever turning on him, without ever having a claim to a voice within their relationship—a quality that would make her instantly undesirable.

The disability theories of narrative prosthesis and the normate perspective thus illuminate the ways in which Lucy Gayheart establishes an arduous leading role for disability while also revealing how poorly its performance will be received. This dramatic dilemma is apparent from the initial appearance of Mockford onstage and Lucy’s subsequent disgust; despite disability being allowed onstage to take its bow, its presence nevertheless unsettles, causing viewers to experience repulsion, fear, or envy in efforts to avoid abnormality. Through her complex exploration of the politics and psychology of narrative accompaniment, Cather creates an original disability aesthetic that critiques the artistic practices of avoiding abnormality. In contrast to the arguments of Stout and Meyer, this new aesthetic does not lift the artist above disability but pulls the artist down by disrupting the processes of both creation and interpretation.

Unsettling readers instead of transporting them to a transcendent realm, Cather opposes an aesthetic that only appreciates strength by demonstrating the essential work of disability’s accompaniment while also revealing why this accompanist is forced to remain backstage to meet the expectations of the normate. The novel’s three endings bring this weight to bear on those in the narrative who have refused it; in Sebastian’s drowning by Mockford, in Lucy’s drowning death, and in Harry Gordon’s lifelong guilt, described as “a wooden leg” (233), Cather constructs permutations of the union of the unsettling accompanist with the artist. By dragging down and unsettling the viewer, Cather’s symbolic endings critique an aesthetic that encourages strength at all costs, particularly at the cost of the well-being of accompanists who have given their energies to sustain art.

Tarnishing and Vanishing: Musical Accompaniment as Narrative Prosthesis

On the night that Lucy sees Clement Sebastian perform, she is impressed by how perfectly he suits the look of a great artist. Large and heavy, he “took up a great deal of space and filled it solidly.” His torso has a pleasantly round shape, “unquestionably oval,” and he is dressed with tailored perfection, “sheathed in black broadcloth and a white waistcoat” (31). Offstage, Sebastian is no different; whether buttoning up his dinner jacket, putting on an overcoat, turning up his collar, or winding a scarf around his neck, Sebastian is usually binding up his dress and appearance to maintain its shape. As Susan Rosowski has argued in The Voyage Perilous, Cather suggests vampiric qualities in Sebastian’s formal dress and in his preying on young things: besides Mockford, whom he took on years ago, and now Lucy, there is also his adopted child, Marius (223– 25). But another way of reading these gothic elements in Sebastian is in terms of his insistence on an appearance that is unblemished, tightly contained, and whole.

As with his articles of clothing, Sebastian seeks accompanists who will round out his performances. We learn from Mockford that Sebastian has been searching eagerly over the years for replacement accompanists—“he rather fancies breaking in a new person”—but that he is almost never satisfied with replacements because they are not “personally sympathetic to him” (61). The criterion for that personal sympathy becomes clear only when Lucy tries out for him. Despairing aloud that she has been too timid in execution, Sebastian reassures her that the only important thing in accompaniment is an absence of ugliness. “The point is,” he says to her, “you do not make ugly sounds; that puts me out more than anything” (38). After returning to her own apartment, Lucy thinks admiringly about the orderliness of Sebastian’s apartment, unconsciously summarizing Sebastian’s aesthetic in a single phrase: “Evidently nothing ever came near Sebastian to tarnish his personal elegance” (48).

Ugliness is what Sebastian cannot tolerate in his presence, and so it makes sense that he is hard at work finding a replacement for James Mockford, whose disability threatens to disrupt Sebastian’s performances. Through Lucy, we witness this firsthand: during Sebastian’s first performance, Lucy enters a trance so deep that she does not even notice Sebastian’s exit. However, her trance is broken abruptly by Mockford’s appearance: “The moon was gone, and the silent street.—And Sebastian was gone, though Lucy had not been aware of his exit. The black cloud that had passed over the moon and the song had obliterated him, too. There was nobody left before the grey velvet curtain but the red-haired accompanist, a lame boy, who dragged one foot as he went across the stage” (32– 33). The sound and sight of Mockford’s dragging foot breaks the spell of Sebastian’s performance, upsetting its ambience. When Lucy sees a second performance, she focuses even more upon Mockford’s unpleasant effects, as she says to herself that his walk across the stage bothers her: “His lameness gave him a weak, undulating walk” (41). Mockford’s limping gait clashes with Sebastian’s elegance, taking away from its power by rendering it weak and ruffling its smoothness with its undulations, its irregularities.

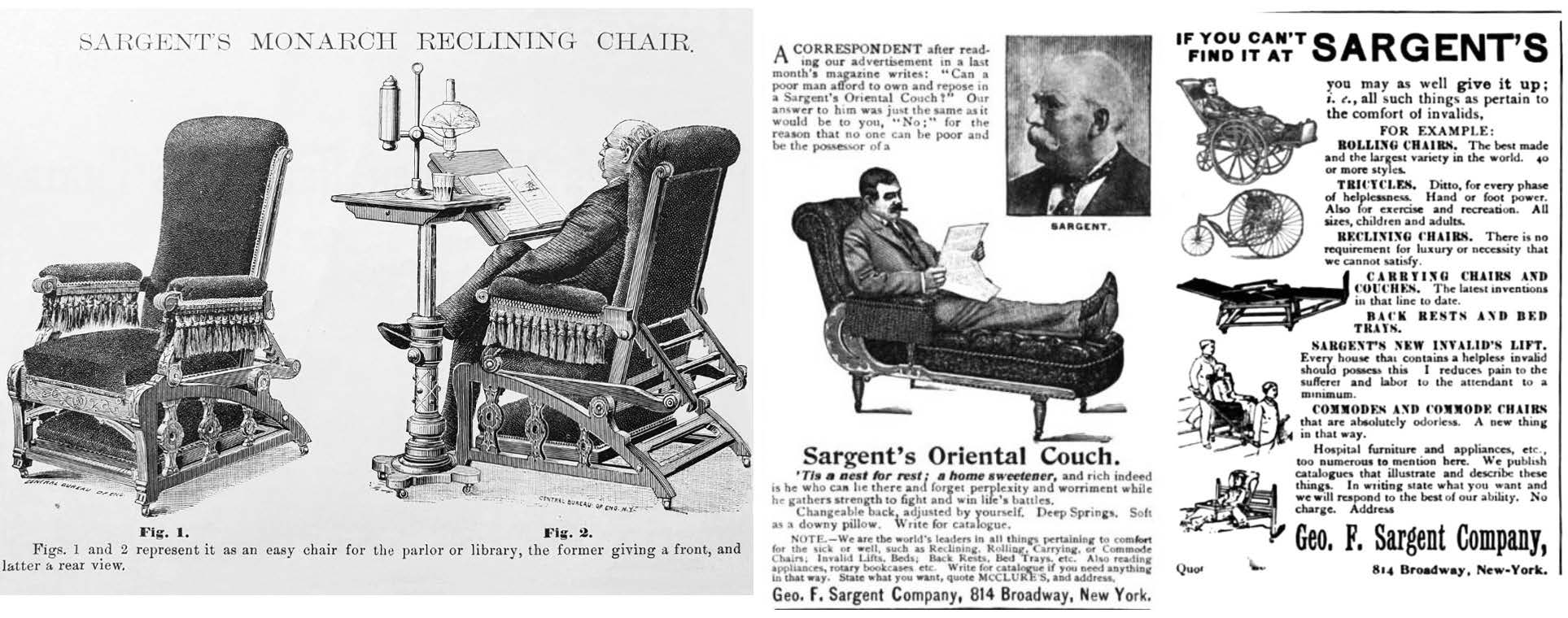

Mockford’s ugliness is not only problematic onstage but also off, as Sebastian and Lucy struggle repeatedly with his intrusions upon their tête-à-têtes. Mockford interrupts them when he comes to Sebastian’s apartment requesting a favor several times—train tickets, a cab ride, a place to store his chair before their tour—and even though these requests might not appear unusual from a long-term friend, Sebastian nevertheless calls Mockford’s manner “brassy” and impertinent (97). Mockford strikes Lucy and Giuseppe in the same way. Lucy describes his fingers as “insinuating” and thinks of him as “selfish and vain” (41, 64), and Giuseppe complains of Mockford’s request to keep his large lounge chair in the apartment, calling it an “ugly chair” that belongs in a secondhand shop (130); it is the chair Mockford uses to stretch out his bad leg. As furniture pieces, lounge chairs have the power to evoke high art through their association with painting studios, the chaises longues that elongate the figures of the most beautiful painting subjects in the world. However, as so-called invalid furniture, Mockford’s lounge chair brings to mind only illness and shabbiness, his body’s imperfections. Like his limping gait, Mockford’s chair mars Sebastian’s beautiful canvas.

Fig. 13.1. Mockford’s “ugly chair” straddles the line between high-art

furniture, like an artist studio’s chaise longue, and

functional patent furniture, like chairs and recliners. Advertisements for

adjustable lounge chairs from New York patent and “invalid furniture” maker

Geo. F. Sargent Company: (left) the Monarch recliner

(Van Dyk); (center) the Oriental Couch (McClure’s); (right) a general

advertisement for “invalid furniture” from Geo. F. Sargent that shows a

range of their available products in the Century

Illustrated Monthly, vol. 49, 1894.

Fig. 13.1. Mockford’s “ugly chair” straddles the line between high-art

furniture, like an artist studio’s chaise longue, and

functional patent furniture, like chairs and recliners. Advertisements for

adjustable lounge chairs from New York patent and “invalid furniture” maker

Geo. F. Sargent Company: (left) the Monarch recliner

(Van Dyk); (center) the Oriental Couch (McClure’s); (right) a general

advertisement for “invalid furniture” from Geo. F. Sargent that shows a

range of their available products in the Century

Illustrated Monthly, vol. 49, 1894.

In contrast to Mockford, with his “brassy” manners and “ugly chair,” Giuseppe and Lucy both aspire to make no ugly sounds, indeed, to make no sounds at all. After Sebastian changes into formal dress, Giuseppe compliments his beautiful appearance, “‘Ecco una cosa molto bella!’ [...] before he vanished through the entry hall” (52). Small and unassuming, Giuseppe is desirable as a servant to Sebastian precisely because he serves then disappears without leaving a trace. “I haven’t a friend in the world who would do for me what that little man would,” Sebastian tells Lucy, for Giuseppe serves without brassiness (47). Like Giuseppe, Lucy is small and unobtrusive, appealing to Sebastian because she vanishes so easily: he first spots Lucy literally hiding behind a pillar (43). It does not take Lucy long to surmise that it is her absence of substance that makes her appealing to Sebastian: “She felt that he liked her being young and ignorant and not too clever. It was an accidental relationship, between someone who had everything and someone who had nothing at all; and it concerned nobody else” (64). Although Lucy recognizes the imbalance of roles in her relationship with Sebastian, she believes she is dependent upon him and owes him gratitude. Much like Giuseppe, she erases her own importance whenever Sebastian is near, and this erasure is what Sebastian seeks in assistants—to prevent ruffles in his perfect appearance.

However, these two vanishing assistants do not believe that they are invisible—quite the opposite, since they regard their meaningfulness to Sebastian as their entire raison d’être. When Sebastian glosses the meaning of Giuseppe’s appearance to Lucy, she is in awe and expresses a great desire to become a sign just as meaningful as Giuseppe:

“I’ve never had better service. Think of it, he has got all those lines on his forehead worrying about other people’s coats and boots and breakfasts.” [. . .]

Something in the way he said this made Lucy feel a trifle downcast. She almost wished she were Giuseppe. After all, it was people like that who counted with artists—more than their admirers. (47)

Envying the furrows in Giuseppe’s forehead that signify his long service to Sebastian’s artistic endeavors, Lucy wants nothing more than to gain meaning by also becoming a legible signal. Indeed, Cather presents Lucy’s escape from Haverford as a hermeneutic search, with Lucy desiring to become a signifier to bring meaning to her world, and she believes she can become one through her service to Sebastian. What Lucy does not notice, however, is the toll of fatigue in that service; both Mockford and Giuseppe, for instance, are presented physically as composites of fresh youth and worn age. Cather suggests that the process of escaping conventional life and becoming a sign in another’s firmament is also wearying and destructive: “it hurt and made one feel small and lost” (14). Initially smothered by the absence of meaning in her small town, Lucy tries to become meaningful in the city but instead dissolves into another smothering embrace.

Having worn out his own meaningfulness, Mockford no longer suits Sebastian, who plans to dismiss him and train Lucy toward the same end. In his plans to eliminate Mockford, Sebastian hopes to replace his disabled accompanist, a man whose impertinence tarnishes the great artist’s desired image, with milder accompanists. According to the terms of Mitchell and Snyder’s theory of narrative prosthesis, Lucy and Giuseppe represent the “cures” needed to eliminate disability’s presence and repair the disruption it has caused. Just as Sebastian is constantly binding up his body with coats, scarves, and ribbons, so he attempts to stitch up the snags that Mockford has left as a prosthesis. This patch job, however, is only part of the story of how prosthesis works. Mitchell and Snyder explain that to understand why the narrative needs to cure itself by eliminating disability, we must first understand why disability was ever invited into the narrative in the first place. Narratives, they explain, cannot come into existence without the aid of deviation, and in the case of representations of disability, that deviation comes in the form of an abnormal body that not only challenges expectations for normalcy but also builds motion into the story, pushing it forward from its complacency. Analyzing the classic tale The Steadfast Tin Soldier, they explain how the soldier’s missing leg acts as the impetus for the entire story’s plot and significance:

The anonymity of normalcy is no story at all. Deviance serves as the basis and common denominator of all narrative. In this sense, the missing leg presents the aberrant soldier as the story’s focus, for his physical difference exiles him from the rank and file of the uniform and physically undifferentiated troop. Whereas a sociality might reject, isolate, institutionalize, reprimand, or obliterate this liability of a single leg, narrative embraces the opportunity that such a “lack” provides—in fact, wills it into existence—as the impetus that calls a story into being. Such a paradox underscores the ironic promise of disability to all narrative. (54–55)

Because they diverge from social order, characters with disability have the unique ability to build narrative meaning. The “ironic promise” that disability as narrative prosthesis provides is that it offers to compensate for a lack in narrative—its absence of deviation—by destroying that normalcy.

Such is the case with Mockford, who besides disturbing Sebastian’s perfection also acts as a narrative source, an origin point for the story’s arc and significance. Indeed, it is Mockford’s disability that gives Lucy her opportunity to become Sebastian’s accompanist, and although Lucy herself admits this debt to Mockford’s disability, she does little to understand the implications of this admission since she is too repulsed by his disability: “It was contemptible to hold a man’s infirmity against him; besides, if this young man weren’t lame, she would not be going to Sebastian’s studio tomorrow,—she would never have met him at all. How strange it was that James Mockford’s bad hip should bring about the most important thing that had ever happened to her” (41). Later she learns that it is this “queer, talented, tricky boy” who teaches Sebastian so much about the German Lieder and who brings him so many years of success through his accompaniment (97). In his notes to the scholarly edition, David Porter rightly points out that it is not unusual for Mockford to demand some recognition for his accompaniment: “Mockford’s wish is to be acknowledged as what any great lieder accompanist must be: a collaborator, not just an accompanist. Sebastian has earlier acknowledged how much he relies on Mockford (‘I’ve got a great many hints from him’ [59]), but here he rejects Mockford’s wish to be more than ‘second fiddle’” (376–77). As Porter suggests, Mockford’s request to be billed as “assisting artist” rather than accompanist is warranted since interpreting the Lieder requires creative ability. And while Sebastian does not deny the fact that he has benefited greatly from Mockford’s talents, even calling him a “little genius,” he refuses to give him that recognition (59).

When we connect disability to the origins of Sebastian’s art, we can better interpret why Cather attributes to Mockford such a strangely artificial appearance throughout the text. Critics have tended to read his ghastly whiteness as a symbolic association with death.[2] However, his appearance is more directly tied to the artifice of the stage and works of art. “He couldn’t help looking theatrical,” Lucy says about him, for “he was made so, and she couldn’t tell whether or not he liked being unusual” (62). Lucy describes Mockford as having curls and dress that make him appear like a statue—“she thought she remembered plaster casts in the Art Museum with just such curls”—and she repeatedly observes that his face is as white as flour, plaster, or paint, a whiteness that disturbs her throughout the novel (41). Mockford’s whiteness appalls not necessarily as a reminder of death but as the whiteness of the page, a place where a work of art comes into being. His whiteness represents artistic fascination and becoming; Lucy cannot stop thinking about it, wishing that “she could get his white face out of her mind” (64). But it also frightens with its otherness, its threat to the story. His white face resembles Stéphane Mallarmé’s abîme blanchi, the whitened abyss of the page that threatens to swallow up the artist’s idealized but unrealized materials (460), for Mockford’s whiteness appalls with its artistic promises and disappointments.

Mockford’s whiteness also acts as a foil to the blackness and shadow that pervade Sebastian and Lucy’s moments together. “The black cloud that had passed over the moon and the song had obliterated him, too,” Lucy says in a trance after seeing Sebastian perform, emphasizing the perfection and desirability of the stage’s emptiness (32). When Lucy becomes Sebastian’s accompanist, she describes her time with him as an event of utter solitude that blots out the representation of a world: “For two hours, five days of the week, she was alone with Sebastian, shut away from the rest of the world. It was as if they were on the lonely spur of a mountain, enveloped by mist. They saw no one but Giuseppe, heard no one; the city below was blotted out” (80). When Lucy is not alone with Sebastian, she is often alone, savoring her memories of Sebastian, and in her thoughts during these moments Lucy often indicates a desire for indistinction, for a dark and shadowy pleasure:

Her memories did not stand out separately; they were

blended and pervasive. They made the room seem larger than it was, quieter

and more guarded; gave it a slight austerity. [...] She put on her

dressing-gown, turned out the gas light, and lay down to reflect. (30)

Lucy often spent the long hot evenings in Sebastian’s music room, lying

on the sofa, with the big windows open and the lights turned out. [...] When

she couldn’t sit still any longer, there was nothing to do but to hurry

along the sidewalks again; diving into black tents of shadow under the

motionless, thick-foliaged maple trees, then out into the white moonshine.

And always one had to elude people. (143)

Hinting at onanistic pleasure in these passages, Cather repeatedly emphasizes the absence of creativity in Lucy’s solitary reflections upon Sebastian by demonstrating the absence of differentiation in her memories: they are dark, blended together, and exist only for her. When Sebastian and Lucy embrace for the last time before his tour departure, Cather describes their union as sublimely pleasurable but having a “blackness above them [that] was soft and velvety” (135). While Mockford’s tarnishing accompaniment contributes to the making of art, Lucy’s and Giuseppe’s accompaniments blot out all representation of a world of difference in efforts to be fully subsumed, to vanish into Sebastian’s undifferentiated solidity.

The dispute between Mockford and Sebastian thus plays out an allegory of narrative prosthesis in which disability’s artistic power is first appropriated to build a work of art by compensating for its absence of abnormality and is then thrown out to erase its presence and return the text to normalcy. Mitchell and Snyder argue that the act of eradicating characters with disability is a punishment that results from the author’s action of attempting to restore normalcy in a text: “Disability inaugurates narrative, but narrative inevitably punishes its own prurient interests by overseeing the extermination of the object of its fascination” (56–57). Indeed, in Sebastian, Cather represents an artist who intentionally “throw[s] over” one of his oldest friends in order to build a more fitting collaboration with a new accompanist (Cather, Lucy Gayheart 104). But Cather also suggests that these efforts at erasing disability’s presence fail, for the story ends when Mockford is thrown away: when Mockford drowns, so, too, does Sebastian. And there is no encore, no collaborative performance of Sebastian with his vanishing accompanist.

Perspectival Gaslighting: "Second Fiddle" Loyalty and the Normate

Perhaps the most challenging part of reading Lucy Gayheart is interpreting the action from the often unreliable perspective of Lucy. Lucy believes to the end, for instance, that Mockford was responsible for Sebastian’s death and that she should have alerted Sebastian “to beware of Mockford, that he was cowardly, envious, treacherous, and she knew it!” (166). Even though she never admits her suspicions to Sebastian, she certainly makes clear her own dislike for Mockford after every encounter with him, describing him as vain, insinuating, and untrustworthy. Critics have tended to adopt Lucy’s distrust for Mockford, viewing him as a negative character, particularly one who symbolizes death and self-destruction. James Woodress has read Mockford as a “sinister homosexual” and jealous “rival for Sebastian’s affections,” arguing that he ultimately triumphs in his duel against Lucy (451). David Stouck has read Mockford as a theatrical personification of Death whose limp represents the creeping resolution of mortality (219–20). Likewise, Susan Rosowski has argued that, with his ghastly whiteness, Mockford represents death and a vampiric rapacity for youth and beauty. Reading his death as a metaphor for Sebastian’s clinging to Lucy and draining her of vitality, Rosowski also trusts Lucy’s interpretation of Mock-ford as a harbinger of death and destruction (“Cather’s Female Landscapes” 242).

However, there are a number of reasons not to fully trust Lucy’s observations on Mockford. From her first sight of him onstage, Lucy emphasizes how Mockford makes her extremely uncomfortable. When she meets him for the first time face-to-face, she tries to understand the confusing effects of his manner upon her: “His manner was a baffling mixture of timidity and cheek. One thing was clear; he was uncomfortable in her company, and certainly she was in his” (62–63). For a moment she wonders if it is jealousy that is causing her dislike, but she waves that idea off; she certainly does not, however, dismiss the idea that Mockford himself is motivated by jealousy. In her nightmare, she imagines Mockford as consumed with murderous jealousy, his “green eyes [. . .] full of terror and greed” (166).

With her theory of the normate, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson offers clues for understanding Lucy’s reactions to Mockford, both onstage and off. Garland-Thomson argues that reactions to the disabled when they are onstage differ from real-life encounters because of the psychological and physical stressors that occur to the non-disabled in their efforts to adhere to the boundaries of normalcy: “The interaction is usually strained because the nondisabled person may feel fear, pity, fascination, repulsion, or merely surprise, none of which is expressible according to social protocol,” while a “nondisabled person often does not know how to act toward a disabled person: how or whether to offer assistance; whether to acknowledge the disability... . Perhaps most destructive to the potential for continuing relations is the normate’s frequent assumption that a disability cancels out other qualities, reducing the complex person to a single attribute” (12). Indeed, before Lucy has met Mockford, she already has reduced him to his impairment, to a limp rag walking, even scolding herself subsequently for doing so: “It was contemptible to hold a man’s infirmity against him” (41). After the performance, she does not meet Mockford for some weeks, and she expresses great relief that he “never dropped in upon them” (59); however, to her disappointment, Lucy accidentally meets him face-to-face when he answers the door of Sebastian’s apartment: “It was Mockford who opened the door for her and asked her to come in. She drew back and would have run away if she could” (59–60). Despite Lucy’s fear, Mockford politely greets her and invites her in, takes her coat, and brings her a chair, all while walking slowly and with difficulty. The two of them exchange long “searching look[s]” before Mockford reluctantly opens up and shares with Lucy his frustrations about his impending surgery and about having to miss the upcoming season (60). While he talks, Lucy says very little but stares at him throughout, at his eyes, his dress, and his hands, fixating on their strangeness, wondering whether he is wearing a wig or “whether or not he liked being unusual” (62). After Mockford recounts some of Sebastian’s dissatisfactions with touring and his positive review of her accompaniment, Lucy is soon so flustered that she leaves the building abruptly, brooding over her disappointments:

Lucy went down in the elevator, wondering whether she would ever go up in it again. She had dreaded meeting Mockford, but she couldn’t have imagined that such a meeting would break her courage and hurt her feelings. She fiercely resented his having any opinions about her or her connection with Sebastian. This was the first time a third person had in any way come upon their little scene, and she hated it. [...] She felt that this strange man who was neither young nor old, who was picturesque and a little repelling, was not altogether trustworthy. (63–64)

In her extreme skittishness, her paralysis, and in her staring throughout their encounter, Lucy demonstrates what Garland-Thomson describes as the confusion and frustration of the nondisabled when failing to sort out proper social behaviors. Moreover, her “fierce resent[ment]” against Mockford for sharing Sebastian’s favorable opinion about her reveals Lucy’s immense insecurities (63). Besides offering insight into Lucy’s psychology, Garland-Thomson’s theory also helps to explain how Lucy’s misreading of Mockford as repulsive, fascinating, and above all threatening emerges from an underlying ideological problem of trust in the novel. Garland-Thomson argues that in encounters with disability the nondisabled unconsciously construct the normate position in opposition to the disabled in order to validate their normalcy: “The term normate usefully designates the social figure through which people can represent themselves as definitive human beings. Normate ... is the constructed identity of those who, by way of the bodily configurations and cultural capital they assume, can step into a position of authority and wield the power it grants them” (8). Although Lucy is hired only as a temporary replacement for Mockford, she nonetheless despises the idea that Mockford be included in any discourse that involves Sebastian. In her association with Sebastian, she clings to their union as a relationship that excludes Mockford, whose otherness stretches too far the “little scene” that she and Sebastian occupy (63). Identifying herself with Sebastian and against Mockford, Lucy seeks to inhabit the position of the normate; loyal only to Sebastian, she regards Mockford as an interloper who cannot be trusted.

Lucy’s unshakable loyalty to Sebastian prevents her from perceiving the patterns of mistrustful behavior in all of Sebastian’s relationships. At a moment when the narrative shifts to Sebastian’s perspective, he admits to himself that he has no knowledge of what true companionship is—“[w]ell, he had missed it, whatever it was” (83)—and that his life is a series of failed relationships. Of his best friend, Larry MacGowan, who dies early in the novel, Sebastian laments that their friendship ended long before Larry’s death because of a fight that the two had when Larry visited him years earlier. When Lucy asks about it, Sebastian gives her this account: “I had looked forward to Larry’s visit, but it didn’t turn out well. He didn’t like our house or our servants or our friends, or anything else. He showed it plainly, and I was disappointed and piqued. Our parting was cold. I think he must have been breaking up even then. He was difficult about everything, and he made criticisms that hurt one’s feelings” (88–89). Rather than regret his own action of cutting the friendship off, Sebastian rationalizes ending the friendship by describing Larry’s behavior as pathological—“he must have been breaking up even then”—attributing it to his much later mental illness. Soon after, Sebastian tells Lucy that he plans to fire Mockford because of a dispute, again labeling as unwell a friend who disagrees with him: “He’s all right at bottom, but he’s not well. That makes him peevish. Just now he’s fighting with me; for his rights, he says. Some of his cronies have put it into his head that he ought to be printed on my programs as ‘assisting artist’ instead of accompanist. I won’t have it, and he’s sulky” (97). Mockford has asked Sebastian to bill him as a bigger part of the act, and rather than cooperate, Sebastian decides to reward Mockford’s long and loyal service to him—indeed, Mockford is “one of the few friends who have lasted through time and change” (56)—with a pink slip. In his explanation of their dispute, Sebastian performs the same kind of manipulation with Mockford that he does with Larry, calling him unwell and “sulky” because of his disability and calling his request to be seen as a more equal part of the act an unfortunate result of “peevishness” attributable to his disability.

Although critics have trusted Sebastian in his villainizing of Mockford, it is important to consider the possibility that this characterization fits a pattern of gaslighting, of deceptively painting his friends as abnormal whenever they criticize him.[3] When Lucy is put off by Mockford, Sebastian laughs at her reaction, chiding her for not having “much skill in dissimulation” (97), suggesting in subtext that he certainly does. He has no problem, for instance, telling Mockford that he will give him what he has requested—his billing as assisting artist—when in actuality he tells Lucy that he plans to let him go. From everything that Sebastian has told her, Lucy is encouraged to see Mockford as untrustworthy, and when she directly asks Sebastian if he is indeed disloyal, Sebastian laughs off the question: “Loyal? As loyal as anyone who plays second fiddle ever is. We mustn’t expect too much!” (97). To Sebastian, all relationships are pairings of master and accompanist wherein the “second fiddle” will eventually demand a greater piece of the pie. No wonder, then, that he seeks out the vanishing accompanists, Lucy and Giuseppe, and loves them for being wholly loyal,for never seeking any “claim” upon him. “He wants someone young and teachable, not somebody who will try to teach him,” says Lucy’s teacher, Paul Auerbach, about the kind of replacement Sebastian has requested (36). Fed up with being taught by others, with taking criticism and hints from his accompanists and friends, Sebastian seeks out relationships with others—people who will never clash with him and will stand behind him when he abandons older friends. His deceptive actions perform well the work of the normate, of defining himself as master in opposition to accompanists who, in their abnormality, pose a threat to his position of power. Moreover, the intense loyalties of Giuseppe and Lucy to Sebastian’s normate perspective destabilize their own opinions and reactions, revealing them to be contributors to the ideological shoring up of normalcy.

Sebastian dies shortly after divulging to Lucy his plan to fire Mockford, who clings to Sebastian in a final embrace. While Lucy blames Mockford for Sebastian’s death, seeing him as a hideous “white thing” that drowned him, her interpretation fails to recognize the truth in Mockford’s claims versus the dissimulation of Sebastian (166). As the “white thing” that drags Sebastian down, Mock-ford becomes a nemesis figure. His deadly hold on his partner and friend dramatizes the accompanist’s refusal to be ignored and cast off as dross, as nothing more than “second fiddle” (97).

Embracing the Mocking World on a Wooden Leg: Resolutions through Disability

Following the deaths of Sebastian and Mockford, Lucy’s story comes to a halt. After returning to Haverford, she refuses to teach or even to communicate with others about her despair. It is not until the night of the stage performance of The Bohemian Girl that Lucy’s story begins to move forward again, and once again this change emerges from an encounter with an abnormal body. When Lucy goes with her father and sister to see the opera, she is stunned at how moved she is by the performance of an aging soprano miscast in the role of a young girl. Consequently, she finds herself compelled to assist in the performance: “Why was it worth her while, Lucy wondered. Singing this humdrum music to humdrum people, why was it worth while? This poor little singer had lost everything: youth, good looks, position, the high notes of her voice. And yet she sang so well! Lucy wanted to be up there on the stage with her, helping her do it” (191–92). While Lucy was initially drawn to Sebastian by his perfection and grandeur, here she is instead attracted to the absence of perfection in this soprano’s presence. It is through the singer’s imperfections that Lucy recognizes her quality, an artistic goodness that draws Lucy in as an accompanist, though this time she describes the work very differently. Rather than feeling a soft and velvety blackness, Lucy describes her choice to return to music as an impending scandal that she will face head on: “Let it come! Let it all come back to her again! Let it betray her and mock her and break her heart, she must have it!” (195). Embracing the storm of life, Lucy communicates her epiphanic comprehension of a new kind of aesthetic economy, one that welcomes the vicissitudes of a “mocking” world upon her own bodily form rather than forcing one to wear out the life of an accompanist. Although Lucy never sympathizes overtly with Mockford, her desire to join the soprano onstage and her subsequent decision to teach music—rather than continue as an accompanist—suggest that Lucy ultimately resolves the problem of cyclic consumption that she witnessed in the artistic pair of Sebastian and Mockford. Moreover, Lucy’s decision to accept the “mocking” world by becoming a music teacher also suggests that she no longer views her small town as a place that is necessarily meaningless. In the few days that remain before her death, she turns toward Harry and the other parts of Haverford in an effort to stop viewing them as limitations that prevent her from having a significant experience of the world. Instead, Cather suggests that Lucy becomes more like the aging soprano, whose imperfections become agents that draw others toward a more meaningful shared experience.[4]

Fig. 13.2. The prosthetic wooden leg found at Cather’s childhood home,

Willow Shade, in a hidden compartment during late twentieth-century

renovations. The leg is thought to have belonged to a family member,

Alfreda, who lost her leg in the 1860s from tuberculosis. Willow Shade owner

Sandy Pumphrey is pictured. Winchester Star/Jeff

Taylor.

Fig. 13.2. The prosthetic wooden leg found at Cather’s childhood home,

Willow Shade, in a hidden compartment during late twentieth-century

renovations. The leg is thought to have belonged to a family member,

Alfreda, who lost her leg in the 1860s from tuberculosis. Willow Shade owner

Sandy Pumphrey is pictured. Winchester Star/Jeff

Taylor.

Despite her final artistic epiphany, however, Lucy still dies in a reprise of Sebastian’s and Mockford’s drowning deaths. Critics have tended to see Lucy’s death as a singular choice of Cather rather than as an organic part of the novel’s action. Merrill Maguire Skaggs, for instance, argues that Lucy is tragically destined to be “dispatched” from the text because she lacks ambition and narrative interest as a character (156–61); indeed, Cather herself complained in a letter about “los[ing] patience” with her heroine’s silliness (Selected Letters 488–89). James Woodress reads Lucy’s death as a natural consequence of “the darkening vision” of “an aging novelist” (449). More recently, David Porter has similarly argued that in Lucy’s death Cather represents her own frustrations with seeing “the brightest of futures prove a fugitive gleam” (“From Song of the Lark” 165). In addition to his biographical reading, Porter also views Lucy’s death as Cather’s representation of the inescapable punishment of the universe, a part of what Cather once described as the “seeming original injustice that creatures so splendidly aspiring should be inexorably doomed to fail” (“From Song of the Lark” 167–68). However, I would argue that Lucy’s death is neither a narrative nor cosmic punishment but rather the tragic and unjust result of Harry’s refusal to help her. It is thus in Harry’s story line that Cather most fully resolves the problem of disability as narrative accompaniment.

Much like Sebastian with Mockford, Harry has always wanted Lucy to act as an accompanist for him. He recognizes that Lucy has “a gift of nature [...] to go wildly happy over trifling things” and that when he is with her, he can “catch it from [her] for a moment, feeling it flash by his ear. [...] His own body grew marvellously free and light, and there was a snapping sparkle in his blood that made him set his teeth” (234–35). However, he only likes to experience this gift through her. Like Sebastian, Harry has an eminent presence, and he is often concerned with dressing well and looking important; however, he believes that he cannot maintain his reputation if he allows himself to take pleasure in “trifling things,” in art and nature. With Lucy, he attempts to sublimate these passions so that he does not have to let them disrupt his life. In fact, in reflections upon his desire to marry Lucy, he thinks of using Lucy as his lifelong “excuse” for experiencing feelings that would normally appear unsuitable in a businessman: “He was full of his own plans, and the future looked bright to him. There was a part of himself that Harry was ashamed to live out in the open (he hated a sentimental man), but he could live it through Lucy. She would be his excuse for doing a great many pleasant things he wouldn’t do on his own account” (114). Like Mockford’s queerness and disability, Lucy’s sensibility offers Harry the chance to live a fine and meaningful life without detracting from his prestige. Harry desires to make of Lucy a prosthesis that will accomplish the wholeness of his own career, appropriating her gifts while also distancing himself from any vulnerability to ensure his ongoing success.

However, once Harry is married, Lucy can no longer be that accompanist for him; consequently, when he sees her, he cannot help being unmoored by the feelings that he has for her and his desire for fineness and grace in his life. In this way, his rejection of Lucy mirrors Sebastian’s rejection of Mockford: the threat of her relationship becoming one of equals, one that will not force her to carry the burden of sentiment, is too much for him and he pushes her away. Like Mockford, Lucy becomes indignant and impertinent toward Harry in the last moments of her life, screaming to him to recognize the injustice of his actions to her. Much later, Harry thinks about this claim in terms of the surprising authority he heard in her voice: “Many a time, going home on winter nights, he had heard again that last cry on the wind—‘Harry!’ Indignation, amazement, authority, as if she wouldn’t allow him to do anything so shameful” (232). David Porter has described Lucy’s final shout as witheringly futile compared to the strong voice of Thea Kronborg (“From Song of the Lark” 152); however, I read her angry call as being extremely powerful. It echoes her exasperated shout at him during their fight in the restaurant in Chicago: “Can’t you understand anything?” (118). Each time they argue, Lucy feels that Harry does not hear her, that he fails to listen. But Lucy has long desired a different kind of relationship with Harry, one where she is allowed to critique him or disagree with him without him turning against her. When she tries to renew ties with him after returning to Haverford, she thinks of their communication as the most important part of their friendship: “If she could only get a message to him, Lucy was thinking as she walked away. She wanted little more than a friendly look when he passed her on the street, the sort of look he used to give her, careless and jolly” (158). Her need for transmitting a message to Harry is brought to a tragic end when she drowns only because she did not know that the river’s bed had shifted. Right before her death she plans to reach out to Harry to ask him about the “new habit the light had taken on” since she had moved away:

Did that pink flush use to come there, in the days when she was running up and down these sidewalks, or was it a new habit the light had taken on? If there was anyone in Haverford who could tell her, it would be Harry Gordon. He was the only man here who noticed such things, and he was deeply, though unwillingly, moved by them. [...] Harry kept that side of himself well hidden. He could feel things without betraying himself, because he was so strong. If only she could have that strength behind her instead of against her! (199)

Lucy’s question, never heeded by Harry, not only requests information that would save her life—we may infer that the light has changed because of the altered landscape and sunken trees resulting from the river’s shifted course—but also asks for a change in their relationship that would place them on more equal footing. Moreover, Lucy requests that Harry recognize his own gifts and hide them less so that the two of them might support each other in their mutual efforts.

But Harry refuses to listen to Lucy’s messages, even when she shouts at him in fury. In his rejection of a plea from his friend who is asking him for a new kind of relationship not defined by accompaniment, Harry resembles Sebastian. However, unlike Sebastian, Harry’s shameful rejection of his accompanist does not result in his own death. Instead, he survives with “a life sentence,” as he calls it, a burden of memory that Cather describes as being like a wooden leg: “‘Well, it’s a life sentence.’ That was the way he used to think about it. Lucy had suffered for a few hours, a few weeks at most. But with him it was there to stay. [...] As time dragged on he had got used to that dark place in his mind, as people get used to going through the world on a wooden leg” (232–33). Representing his accountability to Lucy’s memory as a prosthetic leg, Cather again presents disability as narrative accompaniment and prosthesis; however, while Sebastian treated his disabled accompanist as someone to use up and then cut loose, Harry Gordon does neither with the “wooden leg” of his past. Stopping the cycle of feeding upon the energies of one’s accompanist, Harry incorporates his prosthesis into himself; as Linda Chown describes in her reading of Harry Gordon as the most significant narrator in the novel, Harry “achieves finally an accommodation to his inner self” alone (134). But this accommodation is one that reminds him constantly of his own failure to welcome Lucy when she no longer served him on his own terms. Her footsteps cemented in the sidewalk—a repetition of Mockford’s unsettling gait—are the “white things” that cling to him, pulling him away from an aesthetic that consumes its accompanists.

Conclusion: Unsettling Accompaniment and Disability Aesthetics

Nearly twenty years before writing Lucy Gayheart, Cather was likely beginning to work out some of her earliest thoughts on musical accompaniment and artistic prosthesis, specifically in “The Diamond Mine.” In this story, a Greek Jew named Miletus Poppas is the accompanist to the opera sensation Cressida Garnet. Although Poppas does not have a disability as apparent as Mockford’s, he does have facial neuralgia that makes him suffer in cold, humid air— which explains why he moves to a warm, dry destination in Asia at the story’s end.[5] Poppas differs markedly from Mockford in that his employer is kind and loyal to him, leaving him a fair share of her inheritance; however, like Mockford, he is portrayed as envious and potentially untrustworthy. Cather focuses less on his disability to create these qualities and more on his race, engaging in antisemitic portraiture to call him “a vulture of the vulture race” (Youth 84).[6] Nevertheless, in Poppas we can see an early sketch of Cather’s theorizing of accompaniment and disability, particularly in this passage, where the narrator describes the relationship between Garnet and her accompanist:

Poppas was indispensable to her. He was like a book in which she had written down more about herself than she could possibly remember—and it was information that she might need at any moment. He was the one person who knew her absolutely and who saw into the bottom of her grief. An artist’s saddest secrets are those that have to do with his artistry. Poppas knew all the simple things that were so desperately hard for Cressida, all the difficult things in which she could count on herself; her stupidities and inconsistencies, the chiaroscuro of the voice itself and what could be expected from the mind somewhat mismated with it. He knew where she was sound and where she was mended. With him she could share the depressing knowledge of what a wretchedly faulty thing any productive faculty is. (Youth 98)

Here Cather characterizes Poppas as a receptacle for the parts of Garnet’s artistry that must remain hidden but are also essential to her art. Specifically, Poppas represents a narrative container, a book that records the history of Garnet’s artistry as a series of failures and losses.

Acting as a metaphor for the narrative importance of disability-as-imperfection, Poppas prefigures the characters of Mockford and the aging soprano in Lucy Gayheart. However, this theme is only lightly touched upon in “The Diamond Mine,” as Poppas remains mostly a minor character with narrow symbolic significance. In their theorization of narrative prosthesis, Mitchell and Snyder warn of the unethical problem of employing disability in this way to symbolize artistic imperfection, explaining that the reality and personhood of characters with disability is often overshadowed by symbolic burden: “While stories rely upon the potency of disability as a symbolic figure, they rarely take up disability as an experience of social or political dimensions” (48). Such is perhaps the case with Cather’s portrayal of Miletus Poppas as an accompanist with a disability who is not only racially slandered as a “vulture of a vulture race” but whose disability also acts primarily as a vessel for the theme of imperfection as both necessary and unpleasant to behold.

Lucy Gayheart, however, is considerably more developed in its consideration of ethics. Although the novel does charge James Mockford with prosthetic symbolism, it also draws attention to this action as problematic and harmful to those burdened with this task. Moreover, in the way it represents the deception and jealousy that cloud perception of this harmful process, the novel acts as a metatext for the relationship between narrative prosthesis and the normate, revealing how appreciation for the labor of prosthesis is often made impossible by the perspective of the normate, a viewpoint that projects deception and villainy upon its prosthetic supports in order to validate its power. Denying friendship and courtesy to their accompanists, the examples of Sebastian and Harry deliver a moral of artistic accountability, of imagining ways to embrace the presence of disability in the text rather than expunge it.

One of the ways that Cather imagines this incorporation of disability is through aesthetics, for, in addition to its ethical insights, Lucy Gayheart also offers trenchant aesthetic reflections on the representation of disability as narrative accompaniment. Expressing dissatisfaction with art forms that abandon disparity and heterogeneity, Cather’s novel condemns the practices of conventional aesthetics, emphasizing the continuing need for artists to “embrace the mocking world,” to hone an aesthetic that is open to criticism and maturation.

In his book Concerto for the Left Hand, disability studies author Michael Davidson argues that artistic prosthesis, despite posing the ethical dangers that Mitchell and Snyder decry, can sometimes be executed in such a way that challenges and innovates artistic form. Davidson examines the example of Maurice Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand, a piece that Ravel wrote specifically for concert pianist Paul Wittgenstein—brother to Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein—who lost his right arm in World War I. Davidson argues that the concerto can be read as an unethical artistic prosthesis, a compensatory piece that attempts to normalize and fix Wittgenstein’s impairment; however, he argues that Ravel instead discovers new approaches to musical form by imagining the limits of playing with one hand: “[B]y enabling Wittgenstein, Ravel disables Ravel, imposing formal demands upon composition that he might not have imagined had he not had to think through limits imposed by writing for one hand. Indeed, the Concerto for the Left Hand is a considerably leaner, less bombastic work than most of Ravel’s orchestral music. In this regard, Ravel’s concerto could be linked to the work of artists whose disability, far from limiting possibilities of design or performance, liberates and changes the terms for composition” (2–3).

Fig. 13.3. Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein (brother of philosopher

Ludwig), who lost his right arm in World War I but continued to play and

commission pieces of music written for one hand. Photographer unknown.

Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 13.3. Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein (brother of philosopher

Ludwig), who lost his right arm in World War I but continued to play and

commission pieces of music written for one hand. Photographer unknown.

Wikimedia Commons.

Borrowing a term from theorist Tobin Siebers, Davidson calls this adaptive innovation to aesthetics “disability aesthetics.” He goes on to argue that disability aesthetics often critiques Kantian standards of disinterest by revealing how they ignore the social and bodily origins of aesthetic judgments:

[D]isinterestedness in Kant can only be validated when it appears to elicit a reciprocal response in others. ... Here, the specter of social consensus haunts the aesthetic—as though to say, “My appreciation of that which exceeds my body depends on other bodies for confirmation. The body I escape in my endistanced appreciation is reconstituted in my feeling that others must feel the same way.” It is this spectral body of the other that disability brings to the fore, reminding us of the contingent, interdependent nature of bodies and their situated relationship to physical ideals. Disability aesthetics foregrounds the extent to which the body becomes thinkable when its totality can no longer be taken for granted, when the social meanings attached to sensory and cognitive values cannot be assumed. (3–4)

Davidson eloquently summarizes the ways in which disability aesthetics emphasizes the importance of challenging disinterestedness by reminding the artist that the body is a site not of escape but of destination. The “spectral body of the other” that is conjured through disability’s representation critiques aesthetics that attempt to eliminate the body’s limitations by moving beyond them, demanding instead a “reconstitution” of aesthetic ideals within the disabled body. Artistic appreciation is, then, grounded in relationships of physical and social difference, in the “contingent, interdependent nature of bodies and their situated relationship to physical ideals.”

In Lucy Gayheart, Cather summons just such a “spectral body” to critique artistic disinterestedness as a practice that ignores and dismantles the relevance of corporeal accompaniment. We can see this spectral body literally in the figure of Mockford, whose white form startles Lucy from her aesthetic detachment. Symbolically, the novel contains multiple iterations of spectral bodies and their chilling effects: there is Mockford’s dead body, which clings to Sebastian and reappears in Lucy’s nightmares; Lucy’s frozen corpse, ensnared in a tree submerged in the icy river; and last, Lucy’s ghostly footprints in the cement that Harry preserves. With her death, the novel makes of Lucy herself a spectral body, one that disgraces Harry for failing to recognize the importance of corporeal accompaniment. Like Lucy and like Harry, we are invited to be haunted by the spectral bodies of the accompanists in this novel, to be stirred by their indignant demands to register what is lost when aesthetics become complacent, placid, and self-serving.

Returning, then, to the initial inquiry into Cather’s aesthetics and the role of strength, one may posit that if Lucy Gayheart represents at all artistic triumph over the ill and disabled, it does so in order to critique that kind of art. By contrast, Cather embraces in this novel an aesthetic that opposes bodily perfection and strength by immersing artist and viewer in the undercurrents of corporal uncertainty. The novel’s pageant of spectral bodies works to unsettle the aesthetic acts of construction, reception, and interpretation by recalling the hidden work of disability’s accompaniment. Indeed, Lucy Gayheart enlists its spectral bodies to act as accompanists to the reader’s interpretation, asking the reader to remain open to unsteadiness and incompletion rather than cling to fulfillment. In its demand that disability accompany and unsettle the act of interpretation, Lucy Gayheart recalls what Joseph Urgo has described in his reading of Sapphira and the Slave Girl as planting “dock burs in yo’ pants”: “[T]he Catherian dock bur is a narrative road sign; something that arrests ... to push the reader past pleasure toward transcendence by means of a temporary roughness, or discomfort” (28, 37). But while the hermeneutic image of “dock burs in yo’ pants” is comedic and playful, the ghostly images of Mockford’s grasp and Lucy’s cemented footprints are gothic and funereal. Lucy Gayheart may suggest more than temporary discomfort, instead narrating a parable that exposes the damage that comfortable aesthetics and interpretation can, and often do, cause. Like My Ántonia and The Song of the Lark, Lucy Gayheart narrates the artist’s quest for achieving wholeness; however, like Sapphira and the Slave Girl, it showcases the prosthetic bodies indispensable to this quest and the system of deception required to maintain power over them. Giving audience to these prosthetic figures, Lucy Gayheart involves us in a gripping, >virtuoso performance of disability aesthetics, awakening us to the underhanded practices of an aesthetic that seeks to disentangle itself from its mortal accompaniment.