From Cather Studies Volume 14

Mapping and (Re)mapping the Nebraska Landscape in the Works of Willa Cather and Francis La Flesche

Scholar Tol Foster (Anglo-Creek) argues for the importance of what he calls “relational regionalism,” which examines historically situated writers alongside each other (268). Regional frames, explains Foster, acknowledge tensions, complexities, and multiple perspectives. As he notes, “Native and settler histories and culture are not capable of being separated” (268). However, American literary studies, which began by centering the works of settler writers and which historically mobilized texts for U.S. nation-building purposes, must broaden its frame of reference, urges Foster, to engage with Indigenous authors on their own tribally specific terms to consider ways in which they have worked within and against settler literary traditions (267–68).

Following Foster’s approach, I put the geographical imaginings of Willa Cather (1873–1947) in dialogue with those of a contemporary regional writer, Francis La Flesche (1857–1932) of the Omaha Nation. Specifically, I examine the landscapes of O Pioneers! (1913) and My Ántonia (1918) in relation to those portrayed in La Flesche’s memoir The Middle Five: Indian Boys at School, published in 1900.[1] Different ways of viewing the land and people’s relationships to it emerge through this comparison. Building on insights from critical geography, literary, and Indigenous studies, I examine how these writers’ representations of place respond to the imperatives of settler colonialism. Cather’s novels, I argue, reproduce dominant settler colonial spatial relationships, thereby participating in the naturalization of those forms. La Flesche’s portrait of the Omaha Nation in The Middle Five, in contrast, unsettles depictions of Nebraska as settler space by establishing spatial imaginaries that pre-date and coexist alongside settler spaces.

The regional frame engenders some interesting similarities and contrasts between Cather and La Flesche. In biographical terms, both spent their childhoods in the West and their adulthoods on the East Coast. A settler, Cather came to Nebraska with her family in 1883 and left it in 1896 after graduating from the University of Nebraska. La Flesche was born on the Omaha Reservation in 1857, the son of one of the last principal chiefs of the Omaha people, and spent much of his adult life after 1881 living and working in Washington DC, first for the Office of Indian Affairs and later for the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution. He received an honorary degree from the University of Nebraska in 1926, nine years after Cather received her degree.[2] As writers, both draw on their childhood experiences in crafting their narratives, and their work connects them to the place now called Nebraska. Cather’s early novels cemented her reputation as a writer of the plains and a dominant literary voice of Nebraska. La Flesche wrote or coauthored important monographs on the Omahas, the only tribal nation in that area to retain its pre-Nebraska homelands, and he has been recognized as “the first professional American Indian anthropologist” (Liberty 51). In The Middle Five, La Flesche returns to this homeland as the setting for his memoir. Read alongside each other, O Pioneers!, My Ántonia, and The Middle Five reveal competing geographies. Depictions of the landscape in Cather’s novels establish settler belonging and legitimate the land claims of key characters. In a similar fashion, but with different aims, La Flesche’s narrative asserts Omaha land rights through his depiction of the landscape and his characters’ relationships to it.

My analysis rests on several key assumptions about geography. A place such as the region that Cather and La Flesche represent is productively understood as being both a literal geographic site and a social construct. Places acquire meaning through human actions. A given place may have multiple, contradictory meanings attached to it. In Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism (2017), Native American studies scholar Natchee Blu Barnd uses the term spatiality to convey the sense that “space is a product of our social imaginings and actions, which coalesce into coherence as well as material form. ... In this way, spatiality signals the individual and collective processes we engage in to produce space and the ways that we are also produced by spaces” (13). Artifacts such as maps are not objective recordings of place but cultural texts that reveal the worldview of the mapmaker even as they suggest how others will view and experience this place. Cather and La Flesche as mapmakers then have their own spatialities that reflect their historical and sociocultural locations. I will follow Barnd’s usage of the concepts of Indigenous spatiality and settler spatiality to mark differences around conceptualizations of land and human relationships to it. Barnd reminds readers that “these different spatialities are rooted in the historic and racialized experiences of peoples who experienced colonialism as either colonized or colonizer” (14).

My analysis therefore relies on historical explanations of settler colonialism. Settler colonialism is at its core a geographic project. As historians Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith declare, “settlers come to stay,” and that requires land (2). As part of the process of acquiring land and asserting dominance, a settler colonial state like the United States constructs new geographical entities that, as Barnd describes, displace preexisting Indigenous spatialities. But, as Barnd also shows, this displacement is often partial, with geographical imaginings existing in overlapping tension. Thus, because settler colonialism is a spatial project, it can be contested on spatial grounds.

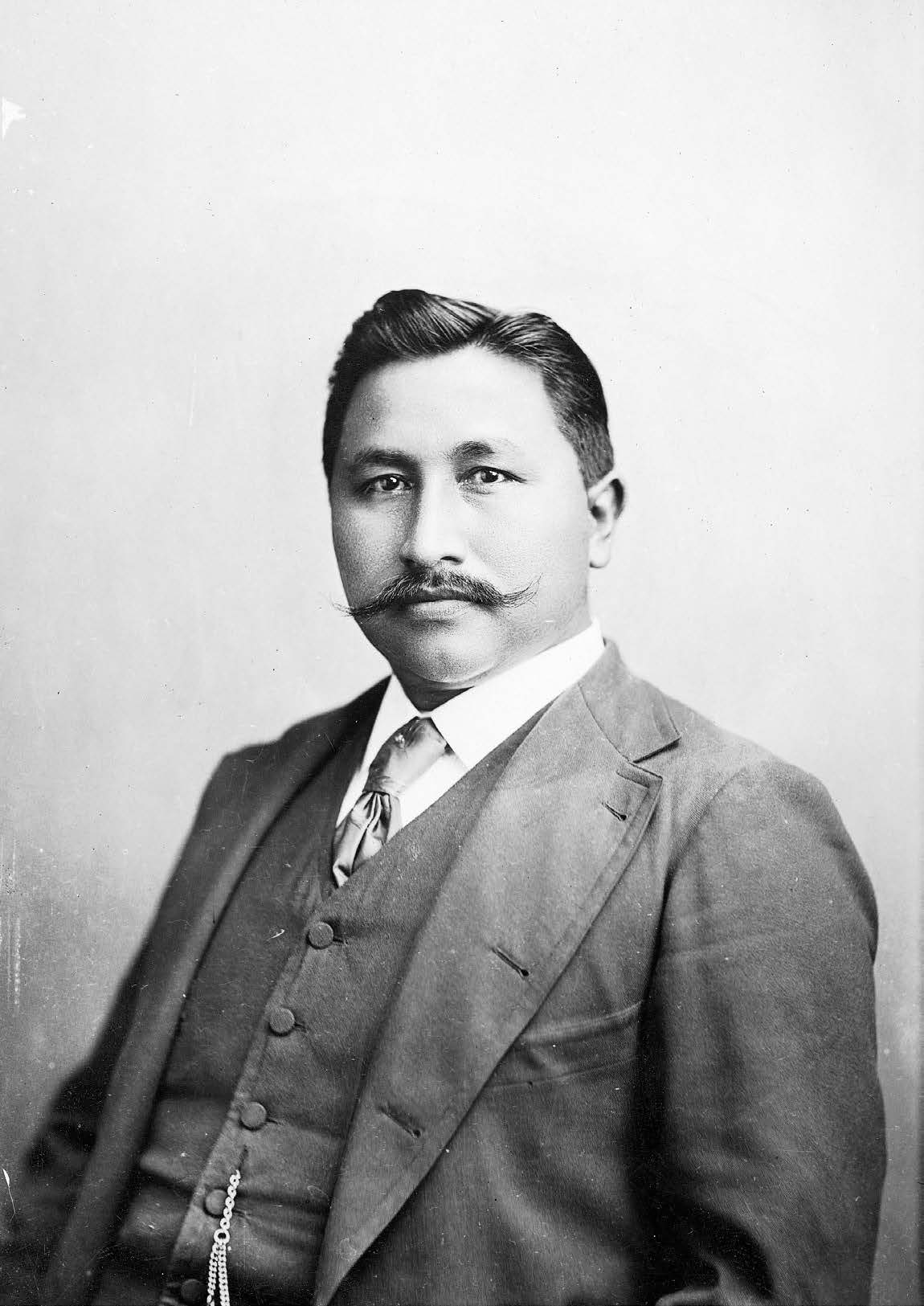

Fig. 8.1. Francis La Flesche, n.d. #00688600. National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Fig. 8.1. Francis La Flesche, n.d. #00688600. National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

In addition to Barnd’s work, I draw on Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman’s theory of “(re)mapping” to explain how settler geographies can be contested by Indigenous writers. In her study of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century Indigenous writers, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (2013), Goeman theorizes “(re)mapping” as a discursive act that “refute[s] colonial organizing of land, bodies, and social and political landscapes” in order to “generate new possibilities” for Indigenous peoples (3). For Goeman, (re)mapping involves two moves: exposing dominant conceptualizations of space that fundamentally reordered Native existence and presenting alternative, sovereign spatialities “literally grounded in ... relationships among land, community, and writing” (13). Although she acknowledges that these sovereign geographies may not dislodge dominant settler ones, they can denaturalize them and call into question the control exercised through spatial arrangements (15). Native peoples, notes Goeman, have historically recognized the role of literature and cartography in legitimizing settler land claims and thus the value of asserting their own spatialities to counter territorial expansion (25–26). In this way, (re)mapping recognizes the power of the representation of place to reinforce or to critique social formations. Using Goeman’s and Barnd’s theories allows me to consider how the works of Cather and La Flesche produce divergent spatialities, clarifying the assumptions about place that animate their depictions of the landscape.

Integral to the process of producing settler space in what is now the United States are the survey and the grid, two spatializations that bear on both Cather’s and La Flesche’s geographical imaginings. In a chapter titled “(Not) in Place: The Grid, or, Cultural Techniques of Ruling Spaces,” Bernhard Siegert explains that, within South and North American settler colonial systems, the cartographic grid represents and orders space to facilitate the control of people, land, and other nonhuman beings (103). Siegert charts how this technique functioned in the United States beginning with the Land Ordinance of 1785, which used a grid-shaped survey to partition the Northwest Territory, an area west of the Allegheny Mountains. The federal government wanted to sell the land to pay off debt incurred during the Revolutionary War. Siegert stresses the importance of this survey technique: “Although the rectangular survey prescribed by the Land Ordinance of 1785 only concerned territories between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, it became the model for the subsequent appropriation and colonization of the entire continent” (112). The survey marked the land with a grid pattern based on longitude and latitude, creating units of geography called townships that were then divided into parcels measuring 640 acres (112). The manner in which these townships and lots were sold created the checkerboard pattern often seen on cadastral maps. In this process of surveying and selling, observes Siegert, “[g]rid patterns, colonization, and real estate speculation coincided” (112–14). The grid survey ultimately covered 69 percent of what has become the continental United States (115). Siegert concludes, “Nothing was left untouched [by the survey]: The rectangular system guaranteed that no shred of land remained masterless. ... [T]he uniform system of rectangular townships and sections assigned to everything—wilderness, plains, forest, or swamp—its own place. Nothing was allowed to fall off the grid” (115). This manner of portioning the land enabled the conceptualization of land as a commodity, an abstract space, seemingly removed from social and political forces (Blomley 127).

Such settler colonial systems of spatial production inform the depiction of the Nebraska landscapes in Cather’s O Pioneers! and My Ántonia. I argue that a view of land as abstract space is integral to these narratives and contributes to their construction of Nebraska as settler space. At first glance, the concept of land as abstract space may not seem relevant to the work of Willa Cather. Previous scholarship has demonstrated the centrality of place in all its particulars to Cather’s imagination.[3] I suggest that images of abstract space work alongside images of particular places in Cather’s fiction to map settler geographies and define settler belonging. Both O Pioneers! and My Ántonia offer scenes in which the reader is given sweeping panoramas of the landscape and scenes that offer close-up views of that landscape (and sometimes both). I trace the relationship between these two ways of looking at the landscape, arguing that close-up views signal the main characters’ affinity for place, while sweeping views reveal the economic control characters exercise over the landscape.

My discussion augments scholarship that has established Cather’s sense of place as fundamental to her artistic production. Susan J. Rosowski’s 1995 exploration of Cather’s environmental imagination, for example, demonstrates that Cather’s interest in the natural and agricultural sciences informed her carefully rendered Nebraska settings, which feature, for example, native plants of the prairies as well as species introduced by farmers (“Ecology of Place” 39–40). These botanical details are emblematic of the ways in which Cather’s settings are “predicated on the uniqueness of place” (42). In a similar vein, Janis Stout describes Cather’s accurate descriptions of nature as a defining aspect of her art: Cather’s focus on selected details against an undefined background creates a feeling of “visual acuity” in her writing (128). Cather’s closely observed settings have also played an important role in her reception as a regional writer, an image Cather herself promoted. As Cather explained to Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant in a 1913 letter, the physical geography of the landscape in which O Pioneers! is set (its lack of “rocks and ridges” and its “fluid black soil,” for example) “influences the mood in which one writes of it—and so the very structure of the story” (Selected Letters 177). Here Cather suggests that the writing of O Pioneers! was made possible through her connection to that part of the country.

In a review of ecocritical interpretations of Cather’s work, Cheryll Glotfelty observes that environmental scenes like those that take place in gardens “are crucial to the signifying system of Cather’s writing” (34). One way in which nature scenes signify is as a marker of character, and scholars have shown that O Pioneers! and My Ántonia validate the characters who closely observe and carefully utilize the landscape. Rosowski, for example, argues convincingly that Cather maps out an evolving region in O Pioneers! that has as its center Alexandra’s placement in and knowledge of the Divide “in all its particularity” (“Ecology of Place” 43). Providing another example, Patrick Dooley argues that an ethical form of stewardship emerges in O Pioneers! and My Ántonia in which the land flourishes under human caretaking. What redeems this type of land use from mere economic exploitation, in Dooley’s view, is that the characters Alexandra in O Pioneers! and Ántonia in My Ántonia work the land for the benefit of future generations (73–75). The larger colonial context is often acknowledged in these discussions, but sustained attention to the ways in which settler colonial spatialities inform characters’ observations and interactions with the landscape in Cather’s fiction is warranted. Taking a close view of the land is part of the process whereby the settler comes to feel at home in a formerly strange and unwelcoming environment. These careful observations make the land legible to the newly arrived. With an ability to read the environment comes affinity for the place. Thus, establishing a character’s rightful place within the landscape is an imperative of settler colonial fiction, as Alex Calder explains in his exploration of Cather’s later fiction (“Beyond Possession”).[4] Calder theorizes that literature concerned with settlement often features the story of a character who attains a deep and authentic relationship to land, appearing to occupy the place naturally. Framed in this way, Rosowski’s compelling interpretation of Alexandra’s “becoming native to a place” (“Ecology of Place” 42) signals the text’s commitment to a story of settler belonging, and Dooley’s reading of Alexandra’s and Ántonia’s careful shepherding of land for the next generation signals the texts’ commitment to ensuring settler futurity through the inheritance of land.[5]

In her discussion of O Pioneers!, literary critic Karen E. Ramirez constructs a useful schema for thinking through the characters’ relationship to land. She distinguishes between what she calls a “place-based” and a “space-based” attitude toward the land. In an ecologically minded, intimate, place-based relationship, as Ramirez describes it, the human connects with nature, believing it to have intrinsic value, and Ramirez demonstrates that Alexandra develops such a place-based relationship (110). Extending Ramirez’s idea to My Ántonia, narrator Jim Burden also comes to enjoy a place-based relationship to the land, as in the famous scene when he is ensconced in the prairie garden and remarks, “I was entirely happy” (18). In both cases, the characters come to feel at home in the landscape, a marker of their integrity.

In contrast to this connected form of being, Ramirez proposes a “space-based” relationship, which is dependent upon an understanding of the land as empty, waiting for humans to capitalize on it: “The land remains imagined as a blank canvas alienated from the human markings imposed upon it” (98). Ramirez shows that this emptying of space is achieved through the cadastral system of mapping described above. Examining O Pioneers! through this schema, Ramirez concludes that, through Alexandra’s characterization as someone who has both a commercial interest in land and a love for it, Cather calls into question the domination of the land. The coexistence within the novel of these different approaches to land, in Ramirez’s reading, potentially destabilizes the text (113). In a settler colonial system, however, appreciation for the land, like that demonstrated by Alexandra and Jim, plays an important role in place-making, as I show in more detail below. Cather’s novels suggest that colonialization and commercialization of the land are not necessarily antithetical to loving it. For example, as explained in the introduction to My Ántonia, Jim’s attachment to land is part of what makes him successful: “He loves with a personal passion the great country through which his railway runs and branches. His faith in it and his knowledge of it have played an important part in its development” (xi). It becomes hard to disentangle these characters’ attachment to the land from their roles in capitalizing on it.

I argue, therefore, that the processes of settlement inform the depictions of the landscape in these two novels. As I discuss in more detail below, these depictions help naturalize settler colonial reorderings of geography that were achieved through mechanisms like the survey and the grid. In settler colonialism, “the settlers come to stay, to seek out lives and identities grounded in the colony and for whom Indigenous people, their rights to land and resources, are obstacles that must be eliminated” (Kelm and Smith 2). This grounding of identity in the landscape is portrayed in the characterizations of Alexandra and Jim. Their relationships to the land follow a similar pattern, from alienation to connection, suggesting Cather’s own experience in Nebraska.

O Pioneers! illustrates how Alexandra becomes at home in the Divide through her careful observations of and heightened appreciation for the land, plants, and animals. Early in the text her father, John Bergson, recognizes the skills that make her the appropriate family member to take over the farm after his death: her keen sense of observation and her willingness to learn about the place they are farming. She studies the stock market, observes her neighbors’ failures, and pays careful attention to their cattle and pigs (28). Later on, her father’s confidence in her is confirmed; Alexandra recognizes that the land on the Divide, rather than the lower land along the river, is better suited for farming at a profit. During a visit with her brother Emil to these lower-lying farms, she takes special note of what other farmers are doing, knowledge that she will later implement to high reward (63). Her first significant epiphany about the land occurs after this visit. The narrator explains her feelings: “For the first time, perhaps, since that land emerged from the waters of geologic ages, a human face was set toward it with love and yearning. It seemed beautiful to her, rich and strong and glorious. Her eyes drank in the breadth of it, until her tears blinded her” (64). This passage emphasizes Alexandra’s literal vision, her ability to take in the vastness of the land without being alienated by it. Alexandra is learning to read the landscape. Here the sweeping view of the land, as she appreciates “the breadth of it,” reveals the control she is beginning to exercise over the landscape. Her vision as a farmer is thus closely aligned to the depth of her feelings for and knowledge of the Divide, and this connection is spatialized in this scene through the act of looking.

Shortly thereafter, Alexandra fully identifies with the land, appreciating both the expanse of nature and its smallest inhabitants. Despite her brothers’ belief that they should give up farming the high lands of the Divide, Alexandra has arrived at a point of emotional and physical connection from which she can successfully develop this farmland. The narrator describes her looking skyward: She always loved to watch them [the stars], to think of their vastness and distance, and of their ordered march. It fortified her to reflect upon the great operations of nature, and when she thought of the law that lay behind them, she felt a sense of personal security. That night she had a new consciousness of the country, felt almost a new relation to it. Even her talk with the boys [her brothers] had not taken away the feeling that had overwhelmed her when she drove back to the Divide that afternoon. She had never known before how much the country meant to her. The chirping of the insects down in the long grass had been like the sweetest music. She had felt as if her heart were hiding down there, somewhere, with the quail and the plover and all the little wild things that crooned or buzzed in the sun. (68–69) In this scene Alexandra’s view takes in nature and leaves her feeling secure. The operations of natural law are knowable to her. Alexandra is no longer alienated from the Divide. Heavily emphasized in this scene, these feelings of security and happy emplacement mark her as settled, and she apprehends this connection in part through the act of looking at nature.

At the end of the novel, the final description of Alexandra imagines her as literally part of the soil out of which the U.S. nation is built: “Fortunate country, that is one day to receive hearts like Alexandra’s into its bosom, to give them out again in the yellow wheat, in the rustling corn, in the shining eyes of youth!” (274). In Settler Common Sense (2014), an analysis of literary works from the American Renaissance, Mark Rifkin examines the everyday ways in which settler colonialism operates to make settlers feel like they belong to the land and that the land belongs to them. These feelings of belonging are not a critique of settler ways of organizing space, of legal and political practices, but a reflection of it; Rifkin explains that “quotidian affective formations among nonnatives [like a sense of belonging] can be understood as normalizing settler presence, privilege, and power, taking up the terms and technologies of settler governance as ... the animating context for nonnatives’ engagement with the social environment” (xv). These emotional responses to the landscape come about through settler colonial structures, not in spite of them.

The movement from feeling alienated to feeling at home, as a manifestation of settler sentiment, is integral to My Ántonia as well. When Jim first arrives in Nebraska, he is not able to locate himself in relation to the topography and feels overwhelmed: “There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made. No, there was nothing but land. [...] I had the feeling that the world was left behind, that we had got over the edge of it, and were outside man’s jurisdiction. I had never before looked up at the sky when there was not a familiar mountain ridge against it. [. . .] Between that earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out” (7–8). Jim emphasizes how he feels disoriented by what he sees and does not see. His feeling of not belonging is spatialized as a lack of grounding in the landscape. He cannot get his bearings because he has no map yet through which to orient himself, no detailed understanding of the features of the environment. He is like the uninitiated observer, “the casual eye” that perceives no variety in the state’s landscape in Cather’s 1923 article “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle” (236). Aileen Moreton-Robinson (Goenpul, Quandamooka First Nation) explains that, in colonial narratives, this sense of alienation from the landscape serves to legitimize settler claims by valorizing the effort it takes to build a place in the new environment (29).

Cather felt a similar lack of orientation when she first arrived in Nebraska as a child. She recounts in a 1913 interview that her feeling of alienation was closely tied to her perception of a landscape without divisions or markers: “The land was open range and there was almost no fencing. As we drove further and further out into the country, I felt a good deal as if we had come to the end of everything—it was a kind of erasure of personality” (Willa Cather in Person 10). Cather had left the familiar countryside of Virginia, tossed “into a country as bare as a piece of sheet iron” (10). From this initial disorientation, Cather developed a keen naturalist’s eye, as Rosowski and Stout have suggested, in part by carefully studying the ecology and botany of the prairies. Cather’s own grounding in place is suggested by her 1923 article, noted above, which opens with a geography lesson explaining the topography and climate of the state (“Nebraska” 236).

In My Ántonia, as the narrative progresses, Jim recalls experiences that connected him to the land as a child. Riding about on his pony during his first autumn in Nebraska, for example, Jim begins to know the land and feel less threatened by the lack of familiar landmarks: “The new country lay open before me: there were no fences in those days, and I could choose my own way over the grass uplands, trusting the pony to get me home again” (27). He recounts his close observations of the natural world: “I used to love to drift along the pale yellow cornfields, looking for the damp spots one sometimes found at their edges, where the smartweed soon turned a rich copper color and the narrow brown leaves hung curled like cocoons about the swollen joints of the stem” (28). Exploring on horseback, observing the local flora, and learning some history of the area allows Jim to map out the space and become attached to it. As in the scenes describing Alexandra’s growing attachment, Jim’s vision and emotional response to nature are emphasized.

Yet Jim’s fullest appreciation for the land and deepest sense of being rightfully in place come as an adult, after he returns to the prairies from the East Coast. The introduction to the novel suggests that Jim feels disconnected from his life in New York City, but returning to Nebraska, he feels an authentic connection, heightened by a visit to Ántonia’s farm. After this visit, toward the close of the narrative, Jim leaves Black Hawk, the town of his youth, behind: I took a long walk north of the town, out into the pastures where the land was so rough that it had never been ploughed up, and the long red grass of early times still grew shaggy over the draws and hillocks. Out there I felt at home again. Overhead the sky was that indescribable blue of autumn; bright and shadowless, hard as enamel. To the south I could see the dun-shaded river bluffs that used to look so big to me, and all about stretched drying cornfields, of the pale-gold color I remembered so well. Russian thistles were blowing across the uplands and piling against the wire fences like barricades. Along the cattle paths the plumes of goldenrod were already fading into sun-warmed velvet, gray with gold threads in it. (358) As with Alexandra, Jim’s feeling of belonging is enhanced through this close observation of the landscape. He knows this landscape, names its constituent parts, and feels an aesthetic appreciation for it. The wild grass is now a memorial to a previous time, domesticated, and not a sign of humans’ inability to make their mark upon the prairies. His eye takes possession of the landscape, the distant bluffs no longer appearing as large as they had when he was younger. He then sheds his adult identity, reconnecting to his younger self in finding the road upon which he and Ántonia had first arrived in Nebraska: “I had the sense of coming home to myself. [...] For Ántonia and for me, this had been the road of Destiny; had taken us to those early accidents of fortune which predetermined for us all that we can ever be” (360). His use of “destiny” and “predetermined” underscores the rightness he feels in being there and gestures to the inevitability of settler occupancy. Jim experiences belonging as a feeling of homecoming. These passages, which come at the end of the novel, signal the landscape’s complete transformation into a known entity—closely observed, aesthetically appreciated, and connected to personal stories and memories for Jim. In telling his story, Jim indigenizes his settler identity, rooting it in a known and beloved landscape.

In addition to these characterizations of a settler’s sense of belonging that derives from close observation and an intimate relationship with the land, Cather reproduces the spatial ideologies of U.S. settler colonial society by mapping out the improvement of unproductive wild lands into productive agricultural spaces in O Pioneers! and My Ántonia. In the scenes I examine below, I attend to three elements that invoke abstract space: the emphasis on a surveyor’s point of view; the demarcation of land into grids; and the suggestion that the economic potential of the land is a product of the disciplining grid.

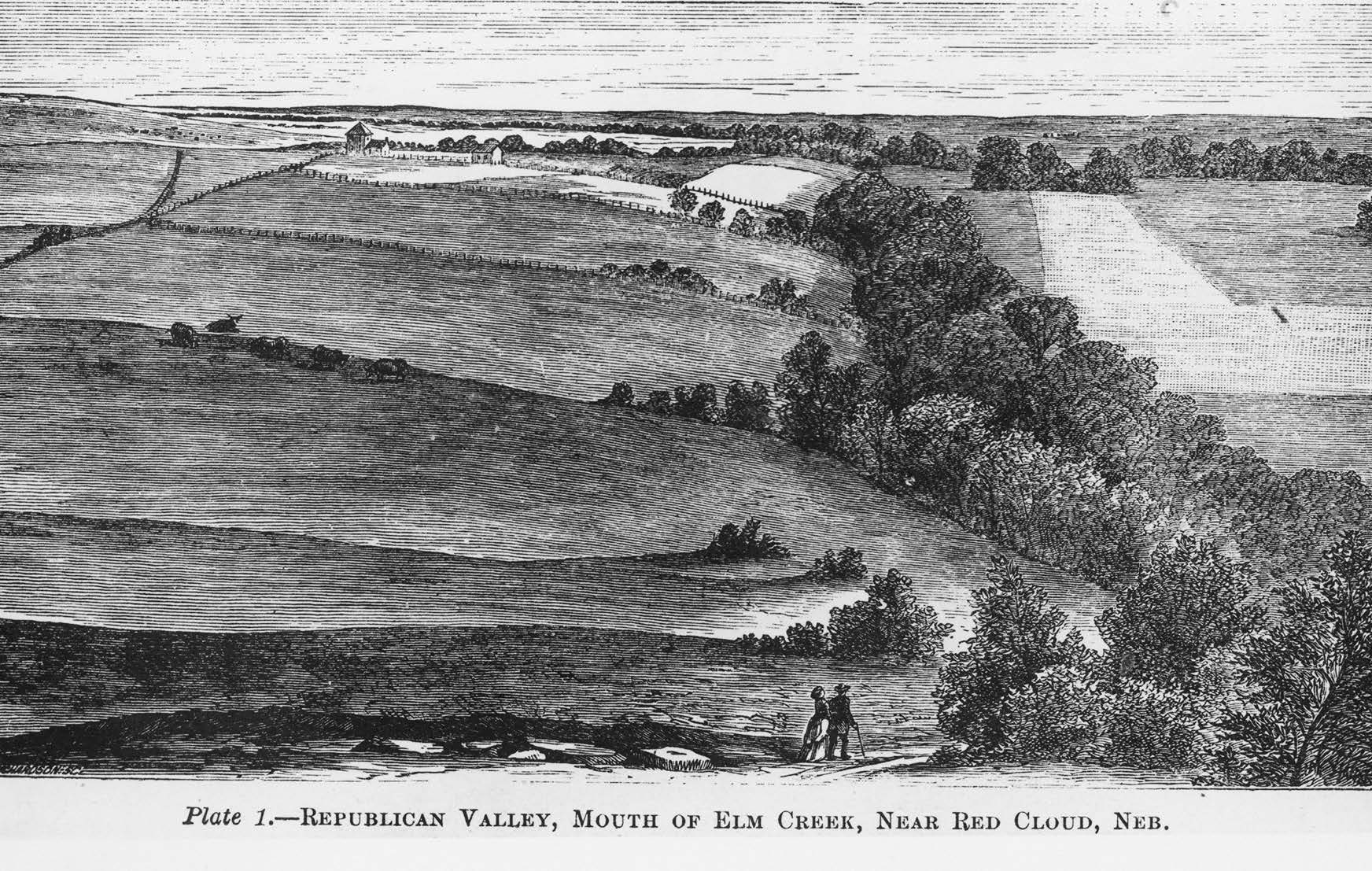

Fig. 8.2. This illustration of Nebraska cropland and pasture is reminiscent of

Cather’s descriptions of the landscape that emphasize the surveyor’s point of

view and the demarcation of the land into grids. Digital object identifier

27955. History Nebraska.

Fig. 8.2. This illustration of Nebraska cropland and pasture is reminiscent of

Cather’s descriptions of the landscape that emphasize the surveyor’s point of

view and the demarcation of the land into grids. Digital object identifier

27955. History Nebraska.

O Pioneers! maps the colonial organization of land and bodies that Mishuana Goeman lays out, and thus I concur with Melissa Ryan’s reading that the enclosure and domestication of the land and people in the interest of nation-building animates this novel. Part I of O Pioneers! advances an emerging settler spatiality. Alexandra’s father, John Bergson, is not yet at home on the Divide, and his view of the landscape underscores this lack of connection. He feels he has not made a definitive mark upon the land: In eleven long years John Bergson had made but little impression upon the wild land he had come to tame. It was still a wild thing that had its ugly moods. [...] Its Genius was unfriendly to man. The sick man was feeling this as he lay looking out of the window, after the doctor had left him. [...] There it lay outside his door, the same land, the same lead-colored miles. He knew every ridge and draw and gully between him and the horizon. To the south, his plowed fields; to the east, the sod stables, the cattle corral, the pond,—and then the grass. (26) His view out the window suggests the incomplete mastery of the landscape, which has not yet been fully defined by the grid. He has some knowledge of the landscape, but the grass marks the limit of his ability to farm the land. The grass resists the imposition of order implied in the plowed fields and farm buildings. Gazing out the window, John Bergson acknowledges that the transformation of the land is incomplete, the land remaining an “enigma” to him (27). The emphasis in this scene on his vision underscores how settler colonialism is a project grounded in the transformation of land and the assertion of a new geographical order.

John Bergson dies before he is able to transform the land, and it then becomes Alexandra’s job to continue what her father began. Alexandra, as explained previously, feels at home on the Divide, and consequently, unlike her father who felt alienated, she views the land with love and learns to farm it effectively. The success of Alexandra’s project and that of other Nebraska settlers is conveyed at the beginning of part II of O Pioneers! through an image of the transformed landscape. The narrator explains what has transpired since the passing of John Bergson: “The shaggy coat of the prairie [...] has vanished forever. From the Norwegian graveyard one looks out over a vast checker-board, marked off in squares of wheat and corn; light and dark, dark and light” (73). The narrative’s vantage point from above, imagining the resurrected body of John Bergson looking out over the cultivated land, allows the human eye to dominate the landscape and registers the visual transformation of land that has occurred since Bergson’s death. In place of the organic image of the prairie as a “shaggy” animal is that of the land regimented by the grid into geometric forms. The vanishing of the prairie thus attests to what historians Roger J. P. Kain and Elizabeth Baigent describe as “the imposition of a new economic and spatial order” (qtd. in Blomley 128). The narrator’s catalog of securely established settler structures conveys the success of this new spatial order. The farmhouses are “gayly painted,” the “gilded weather-vanes on the big red barns wink at each other,” and the windmills “vibrate in the wind” but remain steadfast (73). The novel’s opening images of impermanence—of a town “trying not to be blown away,” of houses “set about haphazard on the tough prairie sod,” and a single “deeply rutted road” (11)—have been replaced by images of physical and economic security. A landscape once lacking order and seemingly empty, as when Alexandra was young, has been replaced by one featuring well-orchestrated roads, a dense population, and fertile, highly productive land (73– 74). The settlers are emplaced; the happiness and fruitfulness of this scene suggest the rightness of their occupancy.

Later in part II, Alexandra’s childhood friend Carl Linstrum confirms this vision of an improved landscape: “He turned and looked back at the wide, map-like prospect of field and hedge and pasture. ‘I would never have believed it could be done. I’m disappointed in my own eye, in my imagination’” (101). Carl’s lamentation about his short-sightedness suggests the fundamental role spatial arrangements play in settler colonialism. Settler colonialism, with its basis in a regime of private property, maps out the land to facilitate ownership and economic development. Because Carl has been away from Hanover, he is able to appreciate the physical changes Alexandra has wrought on the land, changes that indicate the economic development Alexandra has orchestrated.

Two descriptions in My Ántonia of the changes to the Nebraska plains echo Carl’s language. Toward the end of book I, Jim is reflecting on the death of Mr. Shimerda, Ántonia’s father, who had died by suicide. Jim describes how, “[y]ears afterward, when the open-grazing days were over, and the red grass had been ploughed under and under until it had almost disappeared from the prairie; when all the fields were under fence, and the roads no longer ran about like wild things, but followed the surveyed section-lines, Mr. Shimerda’s grave was still there” (114). His description conveys how the survey lines and fences act to regulate the space, acknowledging the imposition of a settler spatial order. But this scene is also full of sadness for what has been lost: Mr. Shimerda himself, who embodied for Jim the best qualities of the first pioneers, and the natural scenes that have disappeared through development. Looking at the crossroads near where Mr. Shimerda is buried, Jim describes how the grave stands in contrast to the regimented landscape of survey lines: “The road from the north curved a little to the east just there, and the road from the west swung out a little to the south; so that the grave, with its tall red grass that was never mowed, was like a little island; and at twilight, under a new moon or the clear evening star, the dusty roads used to look like soft gray rivers flowing past it. I never came upon the place without emotion, and in all that country it was the spot most dear to me” (114). Here, what is valorized is not the domesticated space of the grid but the untouched red grass, a sign of a previous era on the plains. The roads are described using the language of nature, as gentle rivers washing by, in effect softening the impact of humans on the landscape and suggesting a desire for a prairie untouched by settlers.

In connecting My Ántonia to contemporary debates over the importance of preserving land as national parks, Joseph Urgo rightly argues that this scene suggests Jim’s desire to preserve the landscape for personal and aesthetic reasons. The landscape both inspires Jim’s memories and contains them, becoming for Urgo a sign of Cather’s commitment to preserving land, and he likens the grave to “an attenuated national park” (52). Thinking of the grave as a national park suggests how it functions as settler colonial space. In his book-length treatment of settler colonial fiction from New Zealand, Alex Calder examines moments in which settler characters try to erase signs of human impact on the land by going back in time, arguing that such intense nostalgia “is an expression of the misgivings that accompany the transformation of new-world environments, of reservations that have as their literal monument those islands out of time we call national parks” (137).[6] Despite suggesting some misgivings, this nostalgia does not call into question the larger settler colonial project, according to Calder (138). Jim’s nostalgia here acts similarly. Although Jim may have some misgivings about the transformation of the landscape, he continues to play a role in such change as a lawyer for a major railroad. The Shimerda gravesite becomes a kind of touchstone for Jim, a place outside of time, that connects him to that region and to the pioneer virtues that Mr. Shimerda represents. One thinks of Cather’s description of the graveyards in her 1923 article about Nebraska. Looking at the graves of men she knew, Cather invokes this previous generation’s strength of character: “When I stop at one of the graveyards in my own country, and see on the headstones the names of fine old men I used to know ... , I have always the hope that something went into the ground with those pioneers that will one day come out again. Something that will come out not only in sturdy traits of character, but in elasticity of mind, in an honest attitude toward the realities of life, in certain qualities of feeling and imagination” (“Nebraska” 237). Thus, rather than calling settler colonialism into question, these grave scenes confirm the qualities of those who came first and, in Jim’s case, deepen his connection to the region and his feeling of belonging.

A few chapters later, another scene suggests the novel’s validation of the spatial transformation underway. As part of Jim’s explanation as to why corn grows so well in Nebraska and Kansas, he states, “The cornfields were far apart in those times, with miles of wild grazing land between. It took a clear, meditative eye like my grandfather’s to foresee that they would enlarge and multiply until they would be [...] the world’s cornfields; that their yield would be one of the great economic facts [...] which underlie all the activities of men, in peace or war” (132). This scene emphasizes the visual transformation of the landscape and ties it to the creation of a new economic order. This connection is spatialized through the act of looking; Jim’s grandfather is able to visualize the agricultural means through which to build a nation and a global power, a vision that escaped John Bergson in O Pioneers! but was recognized by Alexandra, who “felt the future stirring” once she connected fully to the land (69). Jim establishes the inevitability of this reordering of space through the use of the literary device prolepsis. In his book, Calder theorizes prolepsis, in which a future development is presented as already existing, to be an important element in the settler’s plot. In this scene in My Ántonia, Jim is explaining what happens out of chronological sequence. At this point in his story, Jim is living on the farm with his grandparents, and the settler transformation of the land is still in an early stage. By mentioning the partitioned, developed landscape at the end of book I before it happens, Jim suggests the inevitability of what is to come.[7] Thus, this prolepsis creates what Barnd calls “a predestined American geography” (128). In Jim’s figuration, the land exists as an abstract entity, the engine that powers U.S. national development, and its transformation is the telos of Nebraska’s settler history.

Susan J. Rosowski describes a visual dynamic in Cather’s early fiction—one that is especially notable in O Pioneers!—in which the narrative moves “between the inclusive and the particular”; from wide views of the landscape, the field of vision narrows to describe intimate experiences in nature (“Ecology of Place” 47). I have argued that in appreciating and learning the details of their environments, the characters Alexandra and Jim have come to be at home in Nebraska. These characters’ feelings of belonging are not a critique of settler ways of organizing and utilizing space but come about through settler colonial structures. As Mark Rifkin explains, there is a larger, often unacknowledged political and legal context within which these types of “settler sentiments take shape” (1). In O Pioneers!, John Bergson’s possession of 640 acres indicates such a context (27). As stated in the explanatory notes to the scholarly edition, this figure includes land Bergson obtained through the Homestead Act of 1862 (Stouck 331). Along with other major pieces of legislation in 1862 (the Morrill Act and the Pacific Railroad Acts), the Homestead Act redistributed land taken from Indigenous peoples and was instrumental in furthering the United States’ new spatial and economic order. As Mike Fischer explains in his discussion of My Ántonia, this act was “intended to consolidate control of these [western] lands” (39). The first recorded homestead claim was in Nebraska, and residents of Nebraska and the Dakota Territories filed the most claims under this act (Birk). John Bergson’s 640 acres generate Alexandra’s story; they tie her to the Divide and are the foundation of her success as a farmer. The land’s division into half sections represents a new way of organizing space, which the novel validates through its descriptions of the order and harmony of Alexandra’s farm. Alexandra’s feeling of belonging, which is experienced and expressed as an intensely personal emotion, is engendered by this legal act; the acreage her father obtained under the Homestead Act is the structural foundation upon which Alexandra’s feelings of belonging rest. In My Ántonia, although the source of Jim’s grandparents’ land is not acknowledged, the reader can assume that they also obtained their land through the Homestead Act. As Fischer notes, Jim “has engineered a cleaned up version of Nebraska’s past” (38), one in which the legal acts propelling settler colonial acquisition and management of land are obscured, even as the profits from the commodified land are calculated by various characters.

Ultimately, O Pioneers! and My Ántonia can be regarded as “drama[s] of emplacement,” to borrow Alex Calder’s terminology, in which the territory for the newly arrived is mapped out and settler spatiality asserted (Settler’s Plot 8). Of course, emplacement implies displacement; Aileen Moreton-Robinson convincingly argues that the “fiction of terra nullius”—the colonizer’s belief that no one owned the land and that it was available for inhabitance—authorizes Indigenous dispossession (18). As critics Mike Fischer, Michael Gorman, Melissa Ryan, and Karen Ramirez have shown, to produce the prairie lands as empty space awaiting settler inhabitance, Cather’s two novels erase Indigenous presence—but always partially. These traces, for instance, can be found in My Ántonia’s place-names, like Black Hawk, which Fischer connects to the Sauk leader Chief Black Hawk and the Black Hawk War of 1831–32 (34–35), and Omaha, Nebraska, which represents, as Gorman explains, the nineteenth-century U.S. place-naming practice that memorialized the supposedly vanquished American Indians while “celebrating European territorial supremacy” (41). The scene in My Ántonia in which Jim observes “a great circle where the Indians used to ride” (60) indicates another partial erasure, the vague term “Indian” eliminating any reference to specific tribal peoples and their land claims, as Gorman demonstrates (41–42). In a similar vein, I read Jim’s description as an indication of Indigenous geographies that settler narratives seek to map over but which remain in place.

Fig. 8.3. The front cover of Francis La Flesche’s The Middle

Five (1900). #nby_49697. Newberry Library, Chicago.

Fig. 8.3. The front cover of Francis La Flesche’s The Middle

Five (1900). #nby_49697. Newberry Library, Chicago.

Challenges to settler spatialities, or “alternative modes of mapping and geographic understandings” (Goeman 2), existed at the time Cather was writing. La Flesche’s The Middle Five (1900), with its portrait of daily life in an on-reservation boarding school, presents such an alternative. Countering the production of Nebraska as a settled space, the memoir portrays the Omaha Nation as an enduring entity that pre-dates the state of Nebraska. In my analysis, I distinguish the memoir’s preface, which discusses the reasons La Flesche wrote the memoir, from the body of the text, which covers events from his childhood in the 1860s when he was a student at the Presbyterian mission school. The preface connects the Omaha nation of La Flesche’s youth with the Omaha nation of his adulthood. La Flesche composed and published this memoir while in Washington dc, maintaining his connection with home through regular visits, correspondence with his family, and work on Omaha materials. In the preface to his memoir, La Flesche calls the Omaha territory “our home, the scene of our history, ... our country” (xx). Using the preface (with its unambiguous assertion of Omaha sovereignty over a homeland) to frame the childhood events recorded in his memoir, La Flesche (re)maps Nebraska as Omaha space, “a native space—dense with meanings, stories, and tenurial relations” (Blomley 129). La Flesche’s critique of the transformation of Native territories into U.S. property and national space showcases the Omahas as a self-determining people.

In the preface, La Flesche maps the Omaha reservation as it was in the 1860s, asserting Omaha sovereignty. He begins with a geography lesson: “Most of the country now known as the State of Nebraska (the Omaha name of the river Platt [sic], descriptive of its shallowness, width, and low banks) had for many generations been held and claimed by our people as their own, but when they ceded the greater part of this territory to the United States government, they reserved only a certain tract for their own use and home” (xix). La Flesche offers a brief history of the ownership of the land in question while drawing the reader’s attention to the politics of place naming. He uses the phrase “now known as” to make visible the settler colonial project of geographic transformation, in which Indigenous lands are made into settler space, in part by marking the territory with new names. As noted above, Cather’s novels participate in this process by mapping out a region through the use of actual and fictionalized place-names, some of which invoke Indigenous people and history even as the novels celebrate settler territorial expansion and inhabitance. By inserting the Omaha meaning of the word Nebraska into his narrative, La Flesche disrupts the appropriation of that term to designate settled colonial space. The Omaha word for the river, with its attention to the river’s specific attributes, expresses knowledge that is not conveyed through the use of the term Nebraska to designate the state. Presenting the Omaha people’s intimate knowledge of the terrain, La Flesche underscores his community’s long tenure in this territory and shows how the settler colonial project of unmaking Native space involves a process in which Indigenous “toponymic knowledge is uprooted” (Cogos, Roué, and Roturier 49). La Flesche points out that the name Nebraska has been taken out of its sociolinguistic context, losing its original referent. The meaning has been altered to represent a new geographical configuration, the thirty-seventh U.S. state. In this way, place-names register the displacement, subordination, and loss of control over land experienced by many tribal nations. In noting the change in meaning of Nebraska, La Flesche calls attention to the process “in which the existing mode of representing space is replaced by that of the colonizer and adapted to the needs of the new economic, political, and social order” (Herman 80). Cather’s two novels narrativize this process in showing the productivity of the land under the care of settlers, who, like Alexandra Bergson, have gained intimate knowledge of the terrain. La Flesche challenges that process, while also claiming the space as Omaha.

La Flesche also makes visible settler colonial practices of spatial control, pointing out how an Indigenous people like the Omaha were confined in increasingly smaller spaces through the signing of treaties and the creation of reservations. As Mishuana Goeman and Nicholas Blomley have shown, the new property-based land systems inaugurated by settler colonial powers were highly regulative, defining where Indigenous peoples were allowed (or not allowed) to go and how they should use the land. Yet it is important to note that La Flesche gives the Omaha people some agency in this process, choosing to use the active verbs “ceded” and “reserved” rather than passive verbs; as La Flesche explains, “[W]hen they [the Omahas] ceded the greater part of this territory to the United States government, they reserved only a certain tract for their own use and home” (xix). He reminds the reader that the U.S. government entered into a treaty with the Omahas, a sovereign nation, not a dependent people. Treaties, suggests La Flesche, are not single transactions but commitments to ongoing relationships that entail responsibilities. The Omahas were familiar with Washington’s slowness in fulfilling its lawful obligations. As historian Norma Kidd Green describes, commodities promised as part of the 1854 treaty did not arrive, funds were slow to be dispersed, and agreed-upon buildings were slow to be built (17– 27). The Omahas had to travel to Washington in 1861 to ask that the 1854 treaty be fully honored (28). In fact, in the opening chapter of the memoir La Flesche underscores that many of the buildings on the reservation, like “the Government saw and grist mills,” exemplify treaty obligations: “All of these buildings stood for the fulfillment of the solemn promises made by the ‘Great Father’ at Washington to his ‘Red Children,’ and as part of the price paid for thousands and thousands of acres of fine land” (8). Utilizing quotation marks, La Flesche ironizes contemporary allotment discourse that suggested that Indigenous peoples were like children, dependent upon their fathers for guidance and sustenance, rather than independent, self-governing nations with which the U.S. government had made treaties. He also points to the ways in which land was being transformed through the treaty process. The lengthy descriptions of the mission school and other reservation buildings that precede this comment map out this altered space, and even as La Flesche acknowledges an agreement between nations, his ironic tone raises questions about the fairness of this exchange of “thousands and thousands of acres of fine land” for a collection of buildings, however important they might be to the sustenance of the Omaha people (8).

After La Flesche has established in his preface that the area now known as Nebraska had been, and continues to be, the homeland of the Omaha people, he describes the specific setting of his memoir: It is upon the eastern part of this reservation that the scene of these sketches is laid and at the time when the Omahas were living near the Missouri River in three villages, some four or five miles apart. The one farthest south was known as Ton’-wonga-hae’s village. [...] The middle one was Ish’-ka-da-be’s village. [...] The one to the north and nearest the Mission school was E-sta’-ma-za’s village. [...] Furniture, such as beds, chairs, tables, bureaus, etc., were not used in any of these villages, except in a few instances, while in all of them the Indian costume, language, and social customs remained as yet unmodified. (xix–xx) This is the first physical description of the Omaha reservation the reader is offered. Although the boundaries of the reservation itself suggest the surveyor’s grid that helped facilitate Omaha deterritorialization, the arrangement in villages, which La Flesche maps out via cardinal directions, pushes back against the regimentation of space that settler colonialism enacted. As historian Donald L. Fixico (Shawnee, Sac and Fox, Muscogee Creek, and Seminole) explains, “Originally Native people lived in communities, either sedentary or nomadic. These communities were also called towns, villages, bands, or camps” (474). These communities, either individually or collectively, constituted the tribal nation (476). Thus, in mapping the villages, La Flesche suggests a different way of occupying space, one that reflects a community-based arrangement rather than one based on private property ownership. In Cather’s fiction, although there is an emphasis on farmers helping each other and other forms of community caretaking, private property ownership anchors most characters’ relationship to land, evident in Alexandra’s “squeezing and borrowing” to increase the size of her farm in O Pioneers! (108) and the success of immigrant Anton Cuzak, Ántonia’s husband, in improving the value of their land from twenty dollars an acre to one hundred in My Ántonia (354).[8]

La Flesche also suggests the diversity within the Omaha community. Each of these villages has its own identity, which La Flesche conveys by translating their Omaha names: in Ton’-won-ga-hae’s village, the reader is told, “the people were called ‘wood eaters,’ because they cut and sold wood to the settlers who lived near them” (xix); in Ish’-ka-da-be’s village, inhabitants were called “‘those who dwell in earth lodges’” due to “having adhered to the original aboriginal form of dwelling when they built their village” (xx); and in E-sta’ma-za’s village, the village led by La Flesche’s father, “the people were known as the ‘make-believe white-men,’ because they built their houses after the fashion of the white settlers” (xx). In all three cases, although the inhabitants differ in certain aspects, they are united in their Omaha-ness, what La Flesche calls their “Indian costume, language, and social customs,” which remained intact despite the larger forces being exerted upon them (xx). Anthropologist Mark J. Swetland speculates that the organization of these villages reflects political divisions among the Omaha people over how best to interact with settlers (205, 230). Yet La Flesche’s preface makes no mention of these political differences; instead, in his mapping of the reservation as “home” (xix), La Flesche focuses on what unites the people, how they occupy and utilize the land.

The preface concludes with a paragraph that rejects the U.S. settler colonial view of land as empty space, a view made possible through the surveying and mapping processes discussed earlier and naturalized through Cather’s narratives. In its entirety, the final paragraph reads, “The white people speak of the country at this period as ‘a wilderness,’ as though it was an empty tract without human interest or history. To us Indians it was as clearly defined then as it is to-day; we knew the boundaries of tribal lands, those of our friends and those of our foes; we were familiar with every stream, the contour of every hill, and each peculiar feature of the landscape had its tradition. It was our home, the scene of our history, and we loved it as our country” (xx). La Flesche emphasizes the continuity of Omaha land tenure over time, that the nation was “as clearly defined then,” in the 1860s, “as it is to-day,” at the time of the memoir’s composition and publication, circa 1898–1900. Ending the preface with this unambiguous assertion of Omaha land rights strongly suggests that part of La Flesche’s purpose in writing is to contest dominant spatial imaginings, like those that govern the production of Nebraska as settled space in Cather’s novels. La Flesche refuses the erasure of Indigenous peoples necessary to produce this inhabited place as uninhabited “wilderness” (xx).

The memoir reconnects the land to the Omaha Nation to counter the violence of deterritorialization that sought to sever Indigenous peoples from their emplaced social, political, and cultural relationships. It peoples the territory, (re)mapping it as enduring Indigenous space. Three scenes from the body of the memoir exemplify this assertion of Native space. Although many of the memoir’s scenes take place within the mission school itself, others involve locations across the reservation. As a means of pushing back against the physical restraints imposed by the settler colonial state, La Flesche focuses on movement, in particular the movement of Omaha students and their kin across the landscape. In the second chapter of the memoir, for example, La Flesche relates a story about an experience he had during a walk home from school: “Instead of taking the well-beaten path to the village, we all turned off into one that led directly to my father’s house, and that passed by the burial-place on the bluffs” (16). Walking along, La Flesche or Frank, as he is called in the book, and his school friend Brush observe two white boys eating the traditional offering of pemmican from a bowl that was at the Omaha gravesite. Rushing home, they tell Frank’s mother of “the dreadful things the white boys had done” and receive in return a lesson about Omaha cultural practices: “We listened with respectful attention as my mother explained to us this custom which arose from the tender longing that prompted the mourner to place on the little mound [of the grave] the food that might have been the share of the loved one who lay under the sod” (17). The relatives place the food there, not for the spirit to eat, explains Frank’s mother, but because “people love their dead relatives; they remember them and long for their presence at the family gathering” (17). This scene suggests ways in which the Omaha people use the land in both quotidian ways (as in the “well-beaten path to the village”) and for religious functions such as burial and memorial (16). Frank’s mother is teaching the boys about customs that tie them to their community; the mother’s explanation offers them a different way to map the world, one in which Frank is connected to the land through stories and rituals.

The description of the summer buffalo hunt, the subject of chapter 10 of The Middle Five, also demonstrates Omaha connection to place through cultural practices. La Flesche presents the hunt as a communal activity, one that causes great excitement among the schoolboys. He also contextualizes the hunt as an activity with severe consequences, as indicated by a later reference to the death of Omaha warriors in defense of their hunting grounds (143–44). La Flesche himself actively participated in buffalo hunts before it became impossible to do so (Green 50–52; Swetland 208). The Omaha people’s access to buffalo had been under assault since at least the 1840s, with the scarcity of game being one of the reasons they entered into treaties with the United States (Green 7–9, 27). In the memoir, La Flesche chooses not to suggest the various forces at work to stop the buffalo hunt as a traditional practice. Instead, he articulates an Omaha geography, focusing on the hunt’s importance as a collective event connected to a specific landscape. Frank tells the reader that “immediately after breakfast,” with a “spy-glass” in hand, “we [Frank and some schoolmates who were staying behind] went to a high point whence we could watch the movements of the people in the village nearest the school” as they got ready to leave for the hunt (84). La Flesche engages the surveyor’s view as he looks down from above and afar, but this view does not reveal land in the abstract, as it did in Cather. Frank explains the visual impact of the departing villagers: “It was a wonderful sight to us, the long procession on the winding trail, like a great serpent of varied and brilliant colors. At last I saw my father mount a horse and move forward, the rest of the family followed him, and I watched them until they finally disappeared beyond the green hills. It was nearly noon when the end of the line went out of sight” (84). His descriptions center the bond between the people and the place, as well as his bond with his family and village. The organicism of the “great serpent” image, in which the people move as one, emphasizes their collectivity. Moreover, the villagers move freely, neither their bodies nor the land seemingly subjected to the disciplining forces of settler colonial spatializations like the grid. The buffalo hunt involves an Indigenous formulation of geography, as Barnd has explained in relation to the Kiowa. One way to open up the land to settlers, therefore, was to eliminate the buffalo. Barnd elucidates this idea: “Without traditional subsistence practices [being able to take place], Native space could be effectively unmade, and remade as non-Native or settler space” (94). La Flesche counters by asserting the beauty and purposefulness with which Omaha people collectively use the land in the buffalo hunt.

The third example of (re)mapping involves a farming scene toward the end of the memoir. La Flesche tells the reader about an afternoon spent playing with bows and arrows with his “village playmates”—Omaha children who were not attending the mission school (142). He describes the course of their play: “Our shooting [of arrows] from mark to mark, from one prominent object to another, brought us to a high hill overlooking the ripe fields of corn on the wide bottom below, along the gray Missouri. Here and there among the patches of maize arose little curls of blue smoke, while men and women moved about in their gayly-colored costumes among the broad green leaves of the corn; some, bending under great loads on their backs, were plodding their way laboriously to the fires whence arose the pretty wreaths of smoke” (142).

In contrast to Cather’s image of the Nebraska cornfields as the engine of economic progress and U.S. national development, La Flesche portrays the cornfields here on a smaller, more intimate scale. In place of the survey lines and grid patterns that define the agricultural landscapes of O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, La Flesche describes “patches” of corn and “curls” and “wreaths of smoke,” organic, soft-edged images rather than sharply delineated geometric shapes. In Cather’s depictions of agriculture discussed earlier, no people are visible. In La Flesche’s portrait, the labor of the people working the land is presented. Although Frank is surveying the scene from above, as he did in the hunting scene, he does not present himself as disconnected from the scene. He portrays himself as part of the community, playing with the village boys and enjoying the realization that the smoke signifies a treat: “‘They are making sweet corn,’” one of the boys shouts (142). La Flesche depicts the community as self-sustaining.

In this scene La Flesche utilizes two terms for the crop, calling it both “corn” and “maize” (142). The word maize calls attention to corn’s indigenous roots and to traditional Omaha agricultural practices. At least since 1714, when the Omaha people came to reside near the Missouri River, they had been raising locally available types of maize (Swetland 203). This scene establishes agriculture as an ongoing Omaha method of food production and disrupts the teleology of colonial land usage—that Indigenous peoples did not improve the land and were therefore not entitled to it. This teleology informs Cather’s representation of the flourishing of the former plains once they had been subjected to agricultural improvements. La Flesche alludes to a cross-cultural reality: that Indigenous peoples have been cultivating corn and using it ceremonially in the region now called the Americas for thousands of years (Dunbar-Ortiz 16). In a chapter titled “Follow the Corn,” Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz establishes the migration of corn as a crop throughout the Americas prior to Columbus’s arrival, observing that “Indigenous American agriculture was based on corn” (16). Given La Flesche’s work as an ethnographer recording aspects of various Indigenous cultures and his later founding membership in the Society of American Indians (SAI), the term maize signals a pan-Indigenous perspective.

In fact, La Flesche (re)maps Nebraska not only as Omaha space but also more broadly as Indigenous space. In the chapters “The Ponka Boys” and “A Rebuke,” La Flesche introduces members of two other tribal nations: the Ponca and the Winnebago.[9] Although “The Ponka Boys” details a humorous incident in which Frank and his friends wrestle their sleds back from the boys who had taken them, La Flesche alludes to a more serious history. The memoir’s line that “[t]he Ponkas made a determined resistance” (110) fits the narrative because the boys do not want to give up the sleds, but it also suggests the Ponca people’s resistance against their forced removal to Indian Territory in 1877. Chief Standing Bear led this resistance, returning to Ponca homelands in 1879 to bury his son, whereupon he was arrested. Standing Bear’s successful legal defense resulted in his remaining in Nebraska. La Flesche and his sister Susette accompanied Chief Standing Bear on his lecture tour of the East Coast in 1879–80 to make a case for Ponca land rights (Liberty 52).[10]

La Flesche also alludes to a history of dispossession and resistance in the chapter “A Rebuke,” which centers on the mistreatment of a Winnebago boy. In that chapter, Frank’s father and mother, disappointed that Frank did not defend the Winnebago boy, instruct him about ethical and charitable behavior (127–29). The Winnebago people sought refuge with the Omaha Nation after their forced removal from Minnesota to South Dakota in 1863. The Omahas eventually sold some of their land to form the Winnebago reservation. By alluding to these histories, which feature Indigenous refusals to comply with settler colonial geographies, La Flesche suggests the density and diversity of Indigenous spaces that endured despite the violence being exerted upon them. Thus, La Flesche moves beyond the assertion of Omaha land rights to a pan-Indigenous view. His (re)mapping expands his vision of Omaha space to include kinships and histories with other tribal nations.

Considering as typical the scenes I have examined, such as those relating to burial and mourning customs or subsistence practices, one might interpret the memoir as salvage anthropology. As explained by Michelle H. Raheja, “Salvage anthropology stressed that Indigenous people were destined to disappear off the face of the earth in a matter of years; therefore, great pains should be taken to preserve any Indigenous material or linguistic artifact” (285). Arguably, La Flesche conducted “[t]his anxiety-driven form of anthropology” (Raheja 285). Historian and anthropologist Margot Liberty speculates that, especially in his later work documenting Osage culture, “a sense of almost unbearable urgency may have affected La Flesche” (62). However, The Middle Five was written in a different genre than the ethnographic pieces he produced, and at the time of the memoir’s composition La Flesche had turned from science to explore a “career ‘in letters,’” as it was referred to in discussions and letters between La Flesche and his mentor, Alice Fletcher (Mark 273–77). Most important, the preface to the memoir makes clear his purpose to disrupt the misconceptions his settler audience had and to produce, as I demonstrate above, alternative geographical imaginings. In his memoir, La Flesche restores the land as part of a complex set of social relationships.

It is also important to recognize that La Flesche played a role in the Omaha allotment of 1883–84 as an assistant to Alice Fletcher, which might seem to contradict the assertions of Omaha land rights that I argue La Flesche advances in The Middle Five. Allotment, which was a means to further reduce the land base of Indigenous peoples, exemplified the use of the survey system to convert communally held lands into private property. Allotment thus seems antithetical to the stance La Flesche adopts in his memoir. Yet, as the Ponca and Winnebago stories in his memoir suggest, Indigenous rights to land at the time were precarious. The Omaha people experienced the constant threat of removal, diminishing food sources, and encroaching white settlements (Mark 69–71; Swetland 229–30). Having secure title to their land through allotment seemed to some, like La Flesche’s father, to be the only way to guarantee that their people could stay in their homelands. As a counter to the ongoing precariousness of Omaha land rights stands La Flesche’s opening statement that this place was “home” (xx).

My analysis has uncovered certain commonalities between the works of Willa Cather and Francis La Flesche. In both writers’ works, relationships between the characters and the landscape are spatialized through the act of looking. In addition, emphasis is placed on the emotional response characters have to the landscape. In Cather’s two novels, Alexandra and Jim establish an attachment to the Nebraska plains and eventually come to ground their identity in that place. In The Middle Five, La Flesche demonstrates the ongoing relationship he and his classmates have with Omaha lands as they move about the reservation, enjoying children’s games and participating in communal tribal experiences. Moreover, in the works of both authors, a deep knowledge of the landscape is integral to a sense of belonging. In Cather’s novels, Alexandra and Jim gain intimate knowledge of the prairie lands as part of their growing attachment to the region. La Flesche suggests a particular, enduring knowledge of place in his descriptions, knowledge passed down through generations. For both authors, places serve important functions, such as memorializing the dead. Thus, each writer maps out a region rich in stories and meanings.

Despite such commonalities, Cather’s and La Flesche’s maps fundamentally diverge. Cather portrays the settlement of Nebraska and the resulting transformation of the landscape as inevitable, even desirable. La Flesche asserts Omaha land tenure, pushing back against the U.S. settler colonial idea of the land as an empty wilderness. This notion of empty, abstract space, which was facilitated by land surveys and helped transform Indigenous land into private property, structures Cather’s vision of the landscape. In Cather’s novels, the emptied land becomes the setting for Alexandra’s and Jim’s stories of settler belonging in which improvement to land is the telos of their interaction with it. Cather’s novels establish that the landscape is alien to the newly arrived; in contrast, La Flesche establishes the Omaha Nation as home from the start of his reminiscences. Moreover, La Flesche (re)maps the land to include other tribal nations, poignantly incorporating the story of the Winnebago boy, who has been displaced by colonial reorderings of space. Thus, relationships to place as depicted in these works serve divergent purposes: Cather’s dramas of emplacement erase Indigenous presence and celebrate settler occupancy as right and natural, whereas La Flesche seeks to disrupt the naturalness of settler occupancy by describing the continued tenure and deep love of the Omaha people for their country. La Flesche’s narrative signals a refusal to comply with settler colonial geographies.

Reading Cather, a settler writer, in the context of an Indigenous contemporary like La Flesche, denaturalizes her depictions of the landscape, revealing some assumptions about geography and belonging that I have explored here. In comparing La Flesche’s Omaha memoir with Cather’s two novels (both with autobiographical dimensions), I have become more aware of how, as a settler scholar, my own interpretive practices can be limited by assumptions I have, and I acknowledge with gratitude the scholars whose work I have utilized here to deepen my own thinking. Reading Cather and La Flesche together in the context of these vibrant, ever-growing bodies of interdisciplinary scholarship about settler colonialism, Indigeneity, and literature suggests further rich possibilities for expanding our understanding of Willa Cather as an American writer.