From Cather Studies Volume 14

Willa Cather's "Black Liberation Theology" in Sapphira and the Slave Girl

Pairing Willa Cather with Black liberation theology might seem strange.[1] After all, she is a white writer predominantly known for her work about pioneer-era Nebraska. Yet, before Cather’s exposure to and interest in the variegated immigrant peoples in her second home of Nebraska, she first encountered the dislocated and differentiated peoples of Africa—recently enslaved in the New World—in her native Virginia. This early exposure is not heavily commented upon in Cather scholarship; the bulk of attention has been given to her time spent in Nebraska and the immigrant characters that often inhabit her fiction. What is more, several critics argue that Cather’s Black (and other) characters are constructed from racism. Yet her final novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, returns to her native Virginia. Although this book includes numerous Black characters, it apparently does not disquiet charges of possible racism, despite Cather’s calling her Black characters the “most interesting figures” of the novel (qtd. in Romines, Historical essay 365). My exploration of Black liberation theology—a theology itself grounded in unsettling, differences, and dislocating the white power structures of the status quo—sheds light on Cather’s treatment of race and racism in her final novel.

Eugene Genovese defines Black liberation theology this way: “However much Christianity taught submission to slavery, it also carried a message of foreboding to the master class and of resistance to the enslaved” (165). Thus, “slaves did not often accept professions of white [religious] sincerity at face value; on the contrary, they seized the opportunity to turn even white preaching into a weapon of their own” (190). Black Americans used Judeo-Christian scriptures to forge “weapons of defense, the most important of which was a religion that taught them to love and value each other, to take a critical view of their masters and to reject ideological rationales for their own enslavement” (6). James Cone, the modern author of Black liberation theology, adds that it “matters little to the oppressed who authored scripture; what is important is whether it can serve as a weapon against oppression” (33). Thus, the meanings of various biblical stories and characters are contested, not fixed, producing a tension that plays out among the Black and white characters in the printed work.

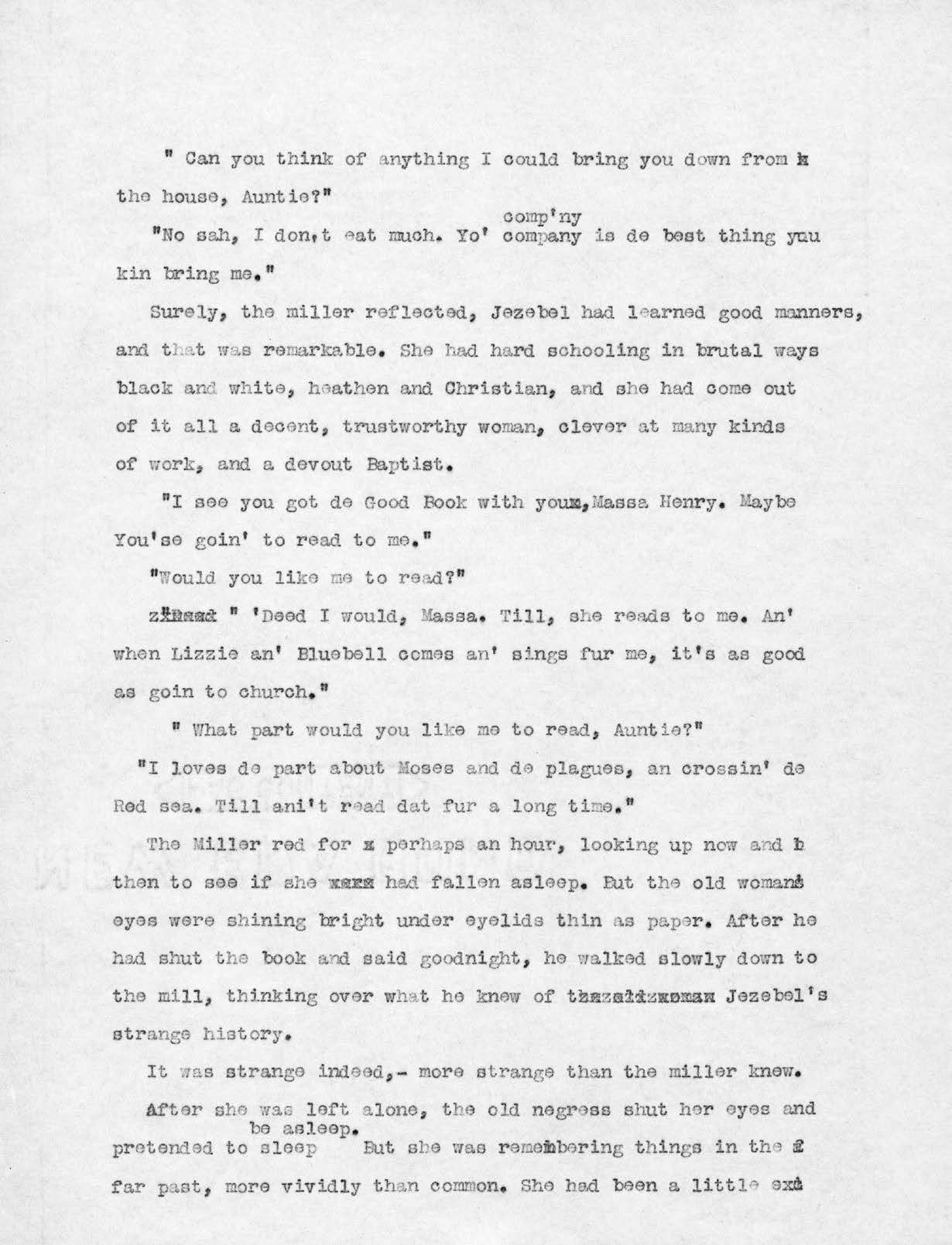

Cather made small but significant changes to her Sapphira and the Slave Girl manuscript that illustrate these complexities.[2] She cut a reference to the Book of Exodus from an earlier typescript in which Henry Colbert, not his wife Sapphira, reads the Bible to Jezebel on her deathbed. In fact, Jezebel requests the reading of slaves escaping bondage, telling Henry that Till often read from that text to the slaves on the Colbert property. Such a reference to Exodus and its escaping enslaved persons would have been a clear and obvious nod to the idea of Black liberation from white bondage—an allusion Sarah Clere calls “profoundly subversive” (444).[3] Indeed, a Black African asking a white enslaver to read Exodus as a comfort before death could only be read subversively. Seeing themselves as “the modern counterparts to the Children of Israel,” Ira Berlin writes, Black Americans “appropriated the story of Exodus as a parable of their own deliverance from bondage” (128). Such an inclusion on Cather’s part would have been a clear and obvious signal to, and even a potential affiliation with, the idea of Black agency, resistance, and sympathy for liberation. It was not included in the novel.

Rather, the scene changes from Henry to Sapphira reading to Jezebel, and instead of Henry asking Jezebel what she wants to hear, Sapphira imposes Psalm 23 upon her audience. The reading is intended to “hearten us both” (89), she tells Jezebel. Indeed, Psalm 23, with its well-known verses such as “The Lord is my Shepherd” and “even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,” is typical Judeo-Christian fare for such an event. However, Sapphira’s reading seems ominous, another instance of her attempts to control and subjugate. In reading this ubiquitous biblical classic, Sapphira might be implying that the only escape from slavery is death. Such a reading gives rise to critical claims of, at worst, Cather’s racism and, at best, an author representing Black characters without agency.[4] A move to cut a clear and obvious textual marker that works against these charges seems strange, yet Jezebel is not as resigned to death as Sapphira may wish. In a moment of “grim humour,” she tells Sapphira that the only thing that might ease her hunger is a “li’l pickaninny’s hand” (90). Here is a subtle moment of resistance woven throughout the novel. Jezebel retains her memory of Africa and a hunger for some agency in either being honest about a desire for human flesh or in subversively entertaining Sapphira’s preconceived notions about Africa.

Even more, Cather did include potentially subversive biblical allusions in the printed novel. Beyond just Psalm 23, she includes in Sapphira references to the Books of Genesis and Daniel, as well as important hymns and spirituals. Much like Exodus, these texts highlight relations between slaves and masters. Indeed, the biblical allusions included in the novel illustrate the differences in reading scripture for the various communities portrayed in the novel. For white Protestants of the historical era within the novel, scripture enforces the status quo in which slaves are expected to obey their masters.[5] For Black readers, however, scripture serves as a means of resistance, a potential for a Black liberation theology—a reading of the Bible by Black Americans used to fuel hope, survival, and/or strategies of resistance in which slaves upend the imperial narrative by defying their masters.

Fig. 2.1. Cather’s typescript for Sapphira and the Slave

Girl features Jezebel’s deathbed request to hear the Book of Exodus

read to her once more. Henry obliges her with a long reading of the Hebrews’

escape from bondage, which she listens to with rapt attention and personal

comfort. Charles E. Cather Collection, Archives and Special Collections,

University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.

Fig. 2.1. Cather’s typescript for Sapphira and the Slave

Girl features Jezebel’s deathbed request to hear the Book of Exodus

read to her once more. Henry obliges her with a long reading of the Hebrews’

escape from bondage, which she listens to with rapt attention and personal

comfort. Charles E. Cather Collection, Archives and Special Collections,

University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.

As such, I argue that Cather’s printed allusions contain potential liberatory ethics that Black readers would identify and white readers might miss. Cather’s changes to the novel to remove the clear and obvious “subversive” biblical texts of her typescript retain the potential for subversion, given Cather’s interest in liberatory texts in earlier drafts. In short, Sapphira and the Slave Girl includes Black liberation theology, whether she intended to or not, despite her cutting the reference to Exodus from earlier drafts. This chapter thus highlights Cather’s cuts and their meanings, offers some explanation as to why she made them, and also describes why and how the included biblical references of the novel can be seen as liberatory. That is, the potential for subversion was on Cather’s mind as she drafted the novel and remains within the printed text despite the deletion of the Exodus material. In all, then, I demonstrate how Sapphira can be read as a subversive text.

This chapter builds upon Sarah Clere’s work on Cather’s earlier typescript by further showing the “possible ways Sapphira could have developed” (442). I agree with Clere that “the novel’s black characters and how to portray them were very much on Cather’s mind when she composed Sapphira” (442). In showing these potential ways Cather’s novel could have gone, Clere rightly contends that Cather was “attuned to many of the historical realities of the antebellum South” (458). As the typescript shows, Cather clearly was aware of the struggles and issues confronting Black people in the South. In this way, in her early composition of the text, her Black characters exhibit far more agency, awareness, and subversion than in the printed novel. In other words, Cather almost champions a liberatory ethic in her exploration of Jezebel in the typescript. Indeed, Jezebel even has more “power and agency” over her own story, one that “shows her taking calculated action in pursuit of a particular goal” (Clere 445). For instance, in Cather’s “Sapphira and the Slave Girl” typescript, the violence Jezebel enacts during her Middle Passage transpires because she is “bewitched and tormented by a thirst to avenge her brothers” (B2F18), whereas in the printed novel the attacks are sporadic and unfocused. In the typescript, she fashions weapons out of the materials given her and chooses her attacks at precise moments based on her watching and assessing the crew’s movements—all signs of Jezebel’s mental awareness and personal choice. Despite moving away from these instances, Cather may have been more attuned to the realities of African agency and resistance than previously thought.

In fact, I argue that the biblical allusions she did include still frame a conversation about liberatory ethics in the context of a white, Protestant, slaveholding U.S. South and Black Americans oppressed by that religious system. A white author connecting the Book of Exodus to a Black character in the context of slavery is a strong and powerful signal of sympathy for that character and perhaps guilt as well. Cutting those elements certainly seems suspect, given the obvious authorial sympathy with the enslaved African character in the novel. But Cather’s texts are not obvious. She shies away from ready-made readings and instead makes interpretation of her work difficult by cloaking her meanings. She is also a writer very much aware of what she is doing. Thus, Sapphira still includes biblical allusions that contain the potential for subversion of the slaveholding order, depending on the reader’s viewpoint.

It is also possible that Cather came upon these moments of Black liberation quite by accident. Toni Morrison in her book Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination explores hidden, unexpected, and unintended meaning and consequences of literary texts when white readers write about Black characters or issues. For Morrison, the writer’s imagination is a place where all sorts of underlying ideas and tensions can play out in a novel, where they “fight secret wars, limn out all sorts of debates blanketed in their texts” (4). More specifically, Morrison is interested in “the way black people ignite critical moments of discovery or change or emphasis in literature not written by them” (viii) in which the “fabrication of an Africanist persona is reflexive; an extraordinary meditation on the self; a powerful exploration of the fears and desires that reside in the writerly conscious. It is an astonishing revelation of longing, of terror, of perplexity, of shame, of magnanimity” that reveals “the self-evident ways that Americans choose to talk about themselves through and within a sometimes allegorical, sometimes metaphorical, but always choked representation of an Africanist presence” (17). Here, Morrison’s analysis shows that Cather, by including biblical and religious materials, may have been teasing such “fears and desires” and that she may not have been fully aware of the impact and meaning upon Black characters. Or, even in teasing out Henry’s wrestling with scripture, she may have been wrestling with these ideas herself, or trying to reconstruct a liberatory history that did not exist for her during her Virginia childhood. It is this “choked representation” of the Exodus material that Cather cut from Sapphira that I want to explore regardless of why Cather did or did not change the manuscript. Her various biblical allusions, both cut from and still within the novel, reveal these “moments of discovery” white Americans use when thinking about their identity in contrast to a Black other. In fact, differing cultural ways of reading the Bible reveal a similar process about identity and cultural formation in which a biblical passage, such as Psalm 23 or the Exodus material, means one thing to a particular cultural group but something else entirely to another.

Black Liberation Theology in the Novel

Indeed, any encounter with scripture has to contend with the reader’s cultural and ideological baggage. A slaveholding white Protestant reading of scripture is different from an enslaved Black American’s reading of the Bible. Indeed, there is “no reading [of the Bible] that is not already ideological” (Bible and Culture Collective 4). Thus, when white readers encounter the statement that servants must “obey in all things your masters” (King James Bible, Col. 3.22) they could likely read the passage as divine justification for slavery. However, when Black readers encounter texts like Exodus and other moments of triumph by downtrodden characters, they see inspiration for a divine liberation from their oppression.

Further, Black Americans derived hope from individual biblical characters. Seeing them as heroes for the present, many Black Christians found inspiration from stories of triumph by individuals who were mistreated. Lawrence Levine, in his book Black Culture and Black Consciousness, articulates such a connection to the Hebrew Bible this way: “For the slaves, then, songs of God and the mythic heroes of their religion were not confined to a specific time or place, but were appropriate to almost every situation” (31). Keith Miller argues that in “identifying with the Hebrews in Egypt and with other Biblical heroes,” Black Americans often “leapfrogged geography and chronology,” and they “telescoped history, replacing chronological time with a form of sacred time” (20) in which Black Americans “freely mingled their own experiences with those of Daniel, Ezekiel, Jonah, and Moses.” These readers “could vividly project Old Testament figures into the present because their universe encompassed both heaven and earth and merged the biblical past with the present.” In this way, Black readers were “freeing those models from any constraints imposed by their historical contexts, and entirely ignoring all barriers separating past and present events” (Miller 20–21). In short, scripture is a weapon. Its stories provide oppressed persons with a source of hope and a means of resisting their oppressors. A Black reader of scripture would likely see the liberatory power in the stories Henry references as well as the hymns Cather includes. Black American readers would likely recognize such stories and allusions as a nod toward their liberatory ways of reading the Bible and singing white-authored hymns such as the abolitionist-composed works mentioned in the novel.[6]

Cather's Cuts from the Typescript

Not only did Cather cut a reference to Exodus, and all that it implies for Black characters in the novel, but Jezebel’s specific references to it are moments of triumph over oppressive orders. In one scene that appears in the typescript, Henry cautiously approaches Jezebel, Bible tucked under his arm. “I see you got de Good Book with you massa Henry, meybe you’se goin to read to me,” she says as he comes closer. Henry asks if she wants him to, and after hearing that she does, he asks her what she wants him to read. “I love de part about Moses an de plagues, an crossin’ de Red Sea. Till aint read dat,” she continues, “fur a long time” (B2F18). There can be no question of Cather’s choice here. The moments Jezebel celebrates are when Egypt is punished by divine retribution for its oppression of the Hebrews. In refusing to release them from bondage despite various plagues being rained upon the country and then in trying to force the Hebrews to come back after releasing them, Egypt is harmed when trying to assert its control over another group. In both of these Exodus scenes Jezebel mentions, the slave community triumphs in violent ways over the administrative and military control exerted over them. Henry’s reading of these particular textual moments seems to animate Jezebel. Instead of the prosaic reading of Psalm 23 Sapphira offers in the published novel, Henry’s reading of scripture “for perhaps an hour” (B2F18) seems to offer hope and comfort for Jezebel as she nears death. Jezebel perhaps imagines a future where something like what is described in Exodus happens to the slave-holding U.S. South. It’s no wonder that a reading of righteous slaves escaping imprisonment and persecution to then form their own nation would be a comfort to Jezebel, the only character in the novel born in Africa.

Indeed, had the passage been retained in the printed novel, it would have had several impacts. For one, it would have given Jezebel and the Black Americans at Back Creek more community and agency—something Ann Romines in her “Losing and Finding ‘Race’” essay argues is largely missing from the printed version. “Cather gives us little sense of the complexity of the slave community” and “how it functioned to facilitate survival and some agency for slaves,” she writes (403). The Exodus allusion provides such a glimpse. What is telling is that Jezebel mentions how Till used to read those passages, presumably often, since Jezebel knows them so well. Even though she hasn’t read them in a while, they were being read by members of the Black community away from the bounds of institutional (i.e., white-controlled) religious practices as a means of resistance, hope for the future, and survival in the context of the established order. The particular sections Jezebel mentions denote violence against that established order, evoking the plagues brought on Egypt as the pharaoh refused to release the enslaved people of Israel. She further mentions the parting of the Red Sea that, when its divinely divided waters came back together after the slaves’ crossing, destroyed the military force sent to bring the Hebrews back into slavery. In sum, when drafting the novel, Cather depicted strategies within the Black American world of Sapphira that preserve and enhance Black identity and resistance.

However, Cather’s considered inclusion also gives justification to the possibility that a novel by a white author dealing with Black characters might create unintended consequences beyond the writer’s control. As Morrison wonders, “What does the inclusion of Africans or African-Americans do to and for the work?” (16). Cather, in her allusion to Exodus, intensifies the idea that Black characters would not care to be where they are in Back Creek or throughout the U.S. South; the Exodus motif thus invalidates the narrative’s offering about happy Black Americans seeking their protection from white masters or leaving the only home they have ever known, as several Black characters are represented as having such feelings after Emancipation and manumission. In enacting an exodus, many formerly enslaved people would happily leave for new lands, wherever that journey might lead them, and would do so without a second thought.[7] The action contained within the Exodus narrative—Israel’s transition out of Egypt, wandering in the desert, and entering the Promised Land—was not easy. In fact, many Hebrews wondered if they were not better off back in Egypt. Further, the Exodus allusion also implies violence—a violence of carving out a place in the Promised Land by defeating the inhabitants of Canaan. In forming the Hebrew nation into a working group after the impact of slavery, conflict is inevitable.

Lastly, the inclusion of Exodus in the published version of Sapphira indicates the need for escape—that Black Americans are in the right for wanting to leave. If Black people in the South are the escaping Hebrews, then white Protestants are Egypt because they have forced Black people to labor for them—a point that Henry makes when musing that Nancy’s escape to Canada suggests that “she would go up out of Egypt to a better land.” However, in thinking how “Sapphira’s darkies were better cared for, better fed and better clothed, than the poor whites in the mountains” (225), Henry immediately undercuts his own beliefs about Black people being more free and better cared for in the South than they would be in the industrial North that lacks the same community context as the U.S. South. Here then is one of Morrison’s moments in which the literary imagination shows the “astonishing revelation of terror, of perplexity, of shame, of magnanimity” (17) in a white writer working with Black characters. In connecting to this Black American’s need for escape, Cather reveals a certain guilt about the rightness of such claims for the need to escape oppression—for what Black people were experiencing in the antebellum United States is indeed oppression by white Americans. Indeed, white characters in the novel experience guilt in helping the enslaved escape. In the published novel, Rachel—Sapphira’s daughter—wonders after she helps Nancy escape if “maybe I ought to have thought and waited” (243). The novel’s epilogue, too, seemingly celebrates Nancy’s emancipation, the need for it, and her life thereafter. However, the narrator still calls her “our Nancy” in a move that undercuts the complete break from the past. The “our” could be familial and intimate, but certainly also domineering and possessive, since the narrator still seems to view Nancy as family property. In all, keeping the Exodus material in the novel would have made the racial undertones of cutting against the grain of white gentility and beneficent southernness much more evident.

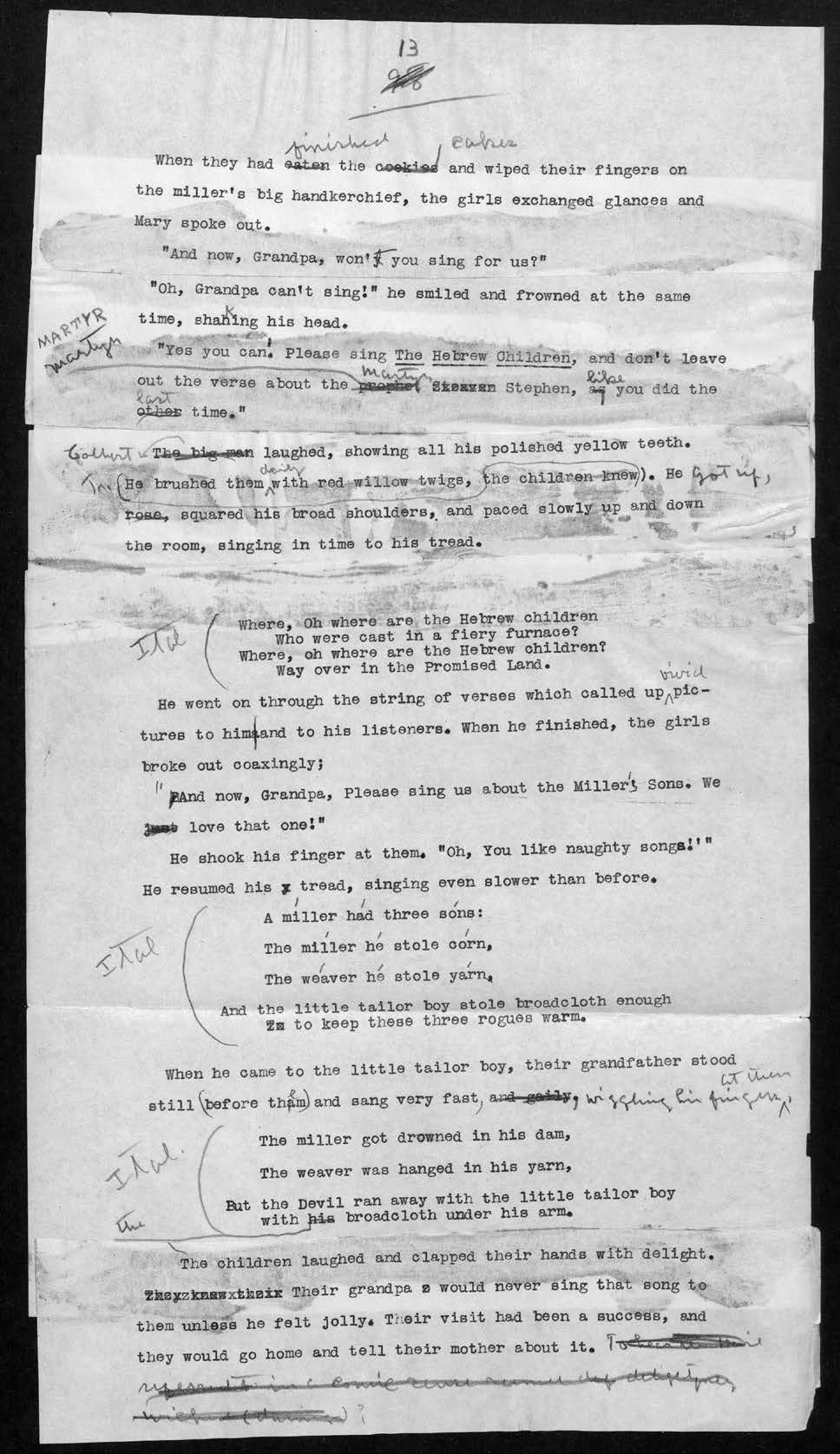

Further, Cather included a scene in the “Sapphira” typescript in which Henry’s grandchildren want him to sing a song about the Hebrew children and the fiery furnace, referencing another instance of maintaining one’s cultural heritage in the face of imperial pressure to change and one in which simple defiance leads to an upending of the established order. The portion Henry sings for them that “called up pictures to him and to his listeners” asks, “Where, o where are the Hebrew children / Who were cast in a fiery furnace? / Where, o where are the Hebrew children? / Way over in the Promised Land” (B1F25P13). Here, the song conflates elements from the Books of Daniel and Exodus. In the Daniel story, three Hebrews are cast into a fiery furnace by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar for refusing to bow down and worship the golden statue of himself. They defy the imperial order as it tries to impose its cultural values upon the exiled Hebrews. The three Hebrews refuse, even if it means their death. They are thrown into the fiery furnace but are miraculously saved, unhurt and unscathed upon their release. It is only because they hold to their cultural heritage that they are saved. They are not moved by Babylonian cultural impulses and in fact reject them. In including this biblically based song, Cather’s “Sapphira” typescript highlights yet another clear moment of slaves overcoming their circumstances by maintaining their heritage in the face of imperial domination. Such a move also further incriminates Henry’s blindness to the plight of the Black people he has enslaved.[8] He does not recognize himself as the imperial master whom his slaves who would identify with the Hebrew children in this drama. In this typescript scene, we see Cather pointing to obvious moments of individual triumph over oppression. So, why did these allusions get cut?

I think Tomas Pollard is correct in asserting that Cather’s “characterization requires that the politics of the 1850s surface as background noise for the emotional universe of her characters. Cather’s heavy excising of the original text shows her desire to dampen any political heavy-handedness” (40). The Exodus motif would have been clear, obvious, and potentially heavy-handed—it would not take someone versed in biblical theory to read Exodus and see how it might appeal to Africans and Black Americans in bondage. Janis Stout argues that Cather “refused to become directly ideological” and that her interest was “in writing, in and of itself” (60). In this way, Cather may have cut the Exodus material because it went against her own authorial judgments.

Fig. 2.2. This typescript page for Sapphira and the Slave

Girl features Henry reading a potentially dangerous song about the

enslaved overcoming their imperial masters by holding on to their cultural

heritage in defiance of assimilation. Charles E. Cather Collection, Archives

and Special Collections, University of Nebraska– Lincoln Libraries.

Fig. 2.2. This typescript page for Sapphira and the Slave

Girl features Henry reading a potentially dangerous song about the

enslaved overcoming their imperial masters by holding on to their cultural

heritage in defiance of assimilation. Charles E. Cather Collection, Archives

and Special Collections, University of Nebraska– Lincoln Libraries.

The Printed Novel's Liberatory Moments

Even after Sapphira reads Psalm 23 to Jezebel in her attempt to maintain her power over others, the scene still propels Henry to an intense reading of scripture, just as it does in the typescript version (even if Henry’s reading of the Bible and his subsequent conclusions about what he finds would have put him into sharp relief against the Exodus material he had just read to Jezebel). In both the printed novel and the typescript, Jezebel’s death fosters the following passage:

Henry Colbert had been reading over certain marked passages in the Book he accepted as a complete guide to human life. He had turned to all the verses marked with a large S. Joseph, Daniel, and the prophets had been slaves in foreign lands, and had brought good out of their captivity. Nowhere in his Bible had he ever been able to find a clear condemnation of slavery. There were injunctions of kindness to slaves, mercy and tolerance. Remember them in bonds as bound with them. Yes, but nowhere did his Bible say that there should be no one in bonds, no one at all. (112; B2F18)

As the passage goes on, Henry imagines all people in bonds of some sort and wonders, “Were we not all in bonds? If Lizzie, the cook, was in bonds to Sapphira, was she not almost equally in bonds to Lizzie?” (112; B2F18). For Henry, then, since major positive biblical figures were enslaved, there was no clear condemnation of slavery. Moreover, since people were in bondage to one another anyway, he was bound by southern norms not to condemn or act against the “peculiar institution.” He even equates slaves and masters on “almost” equal terms of servitude to one another, certainly a stance that was far from true in the U.S. South.

Further, Henry’s “complete guide to human life” seems influenced by Calvinist theology and predestination wherein Jezebel and others are enslaved because of some divine plan enacted before the universe was created. Henry certainly cannot interfere with God’s plan. He does imagine a point where the divine plan includes freeing the slaves, and perhaps soon. The Exodus passage itself and Jezebel’s own intense interest in these passages undermine Henry’s ideas about religion as justification for slavery. Henry does not or cannot see himself as Pharaoh in this drama. He does not connect the violence done against Egypt as something potentially comparable to and possible in the U.S. South, while Jezebel and the Black community seem to make that connection, seeing their own future liberation in these stories. From his limited perspective, Henry’s white southern reading of scripture conforms to his cultural surroundings. In his final musings on the above passage, Henry believes that design in nature is clear enough, but he questions how such designs can be accurately seen in human affairs, blaming the “fault in our perceptions” since “we can never see what was behind the next turn of the road” (113). Thus, Henry’s own reading should not be taken at face value. His cultural underpinnings and context need to be considered in his interpretation. It should also be considered, then, that Cather included these allusions for this contested tension within the biblical referents evinced in Henry’s own grappling with scripture, given the passage’s connection to Henry’s Quaker friend who “firmly believed” (113)—correctly—that slavery would be abolished in his lifetime.[9] This contrasting theology shows that action is required to bring about emancipation. As Henry wrestles with theological and cultural questions, the Quakers in the novel work toward emancipation, including helping Nancy escape via the Underground Railroad.

Returning to Henry’s conclusion that there is “no clear condemnation of slavery” in the Bible, his reading is fraught with white expectations that reading scripture will justify their own stance—that is, Henry sees what he wants to see in the Bible when it comes to maintaining the system of slavery. His reading and subsequent conclusions ring hollow. For instance, Henry cites Joseph and Daniel as major biblical figures who were slaves. In his view, since these major figures were slaves and are regarded as significant figures in Jewish and Christian theology and culture, surely slaves in the United States can be regarded similarly and the institution cannot be morally wrong. What Henry misses, however, is that these slaves upend the intended order—they subvert imperial power from their humble position in bonded service. Henry conveniently forgets or chooses not to see that Babylon’s imperial power and excess are the bad actors in the drama. He fails to see that in justifying slavery because of the heroic Daniel’s status as a slave, the United States and its systems of racial oppression are on par with Babylon’s. What the Daniel text celebrates is how the righteous slave overturns state power and oppression. King Nebuchadnezzar and other Babylonian rulers are each brought low by the humble faith and simple defiance of the slaves in the Daniel text—this is the point of the Book of Daniel, a subversive point that Henry does not want to see, nor is he like those who take action to upend the institutional exploitation of others.

Henry misses similar content in referencing Joseph. The Joseph story in the Book of Genesis contains yet another moment of ascension and triumph for a former slave. Sold into foreign slavery by his jealous brothers, Joseph becomes enmeshed within the Egyptian administrative hierarchy, becoming second only to Pharaoh himself in power and stature. Even though he retains his association with Egypt, Joseph maintains fidelity to his heritage and does not become corrupted by the system around him. Even more, Joseph later comes to have power over his brothers who sold him into slavery in the first place. The tension of the drama, then, concerns how Joseph will use his power over those who betrayed him and sold him into slavery. Joseph reveals his true identity to his brothers, and in their terror at realizing their situation, he has mercy on them. Perceptive readers of Cather’s biblical and religious allusions could see how the references might be political after all, depending upon one’s viewpoint. Henry, as a typical slave-holding white Protestant, misses the warning of scripture to oppressive regimes featured in the Bible. His own justifications for slavery belie his scriptural underpinning for that system since the slaves depicted within those stories all succeed despite and against their enslavement. In these stories, too, the ones who impose slavery are the villains. As such, Cather ironizes Henry and his acceptance of biblical justifications of slavery. It is difficult to conceive of Cather siding with Henry here or missing the potential political notes of these allusions, given her clear attention to such texts in the typescript. The potentially unsettling biblical allusions she included in the novel still carry the weight of slaves overcoming their circumstances, although they are more subtle.

The songs and hymns referenced in the novel also contain readings against the grain of white Protestant orthodoxy, including covert references to Moses and the Book of Exodus. Prior to Jezebel’s death scene, Cather includes the hymn “There Is a Land of Pure Delight.”[10] As a church service concludes, Henry joins several of the Colbert slaves, led by the cook Lizzie, who “broke away from Shand,” the elderly white male song leader, “and carried the tune along” (80). It is the Black congregants’ passionate singing that elevates the experience into a “living worship” that punctuates the service more than any other portion of the day’s activities. “Could we but stand where Moses stood,” they sing, “And view the landscape o’er / Not Jordan’s stream nor death’s cold flood / Would fright us from that shore” (81). At the conclusion of their singing, the preacher reacts with “not a smile exactly, but with appreciation. He often felt like thanking” Lizzie (81). The white-authored English hymn is based on the story of how Moses, near death and prohibited from entering the Promised Land for angering God, viewed the Promised Land and knew that, even though he would not enter this new era, the Hebrews he led would. At this moment in Exodus, the Hebrews have finished their wandering in the desert, rid themselves of people still attached to Egypt and its oppressive legacy, and shaped themselves into a nation. They are poised for the next step. That next step—conquering the Promised Land and taking it for their own—is not included in the hymn. Perhaps this is where the preacher has some measure of apprehension, given “those bright promises and dark warnings” sung with “such fervent conviction” by the “Colbert negroes.” In fact, for the Black singers, those “bright promises” and “dark warnings” (80) are moments of Black liberation theology that evoke what is not named in the hymn or the text; the Black singers (and perhaps some of the apprehensive white congregants at the church, too) are seeing the coming freedom from bondage by whatever means necessary. Perhaps, too, the older Black Americans know that, like Moses, they will not live to see this new era, but they know it’s coming; they know it’s close. Cather certainly has the vantage point of history to know this to be the case. It is also telling that this hymn precedes the section on Jezebel, potentially existing as a precursor to that moment.

Henry, too, reflects upon a hymn that contains more meaning than what he might have intended or known. After Henry’s reading of scripture examining the lives of Joseph and Daniel (a reading immediately after Jezebel’s death), the interlinking of these themes concludes with Henry singing/praying William Cowper’s hymn “God Moves in a Mysterious Way.” His night of reading and reflection on the Bible and slavery concludes with him envisioning a time when “a morning would break when all the black slaves would be free” (113). For Henry, this moment is a fait accompli, something God will accomplish at an unknown time in an unknown way. Such a reading dismisses human action and agency in the liberatory drama, something Exodus does not do. Even more, William Cowper, the hymn writer, was a staunch abolitionist. In fact, he wrote “The Negro’s Complaint” in 1788.[11] He was also friends with the writer of “Amazing Grace,” an important hymn that inspired William Wilberforce in England’s abolitionist movement. Henry seems unaware of all of this. Instead, he seems to relegate human action to the background, favoring divine providence without human actors. For Henry, ending slavery is God’s business, not his. In capping his Bible reading with Cowper’s hymn (later used by Martin Luther King Jr. in the U.S. civil rights movement after Sapphira’s publication), Henry ironically cites a prominent figure within abolitionist movements in England that were concurrent to his time, mistakenly using Cowper’s hymn to justify staying out of direct action to end Black oppression.

My point here is that Cather would likely have known these oblique details—her liberatory moments are hidden but still present in the printed novel. This reference could be a sly wink toward abolitionist action by human effort—that political agitation can result in changed circumstances for oppressed people. These references further cloud the idea that slavery itself was beneficial to the enslaved and another moment of divine providence enacted on their behalf. Although he frees the Colbert slaves after Sapphira’s death, Henry never risks anything to do so. His freeing of the enslaved is not a dramatic upending of the antebellum social order, nor is it an economic risk for his property or standing in the community. He does find gainful employment for the formerly enslaved, taking time to ensure they have community and employment, but this poses no challenge to slavery writ large; his actions do not subvert the social order within his family or community life. He does not risk rebuke or challenge from Sapphira, as he would have done if she were still living, and he does not seem to be hurt economically in freeing the enslaved. In fact, to keep the contentious Lizzie and Bluebell from returning, he tells them they are “needed at the mill place no more” (281). Henry might be saying whatever is needed to keep them from coming back, but the emphasis on need is telling— had they, and others, still been needed, would he have freed them? Nevertheless, Henry clearly sees the humanity in Black people and is commended for the trouble he takes in getting “good places fur his people” (281), as Till reports. But he never risks his own standing or person to work on their behalf, as many of those he cites, seeks counsel from, or reads about did. Here, Henry is again ironized by his limited perspective and choice that he cannot (or chooses not to) see. For Cather’s readers—readers with the gift of historical perspective—the irony would not be lost.

Cather’s intertexts matter. What she chooses to include is significant, even if those inclusions were derived from a subconscious reflexivity of a white writer crafting Black characters. The intertexts that remain in the printed version of Sapphira reveal a differing ethics and way of reading scripture between oppressor and oppressed and/or reference figures in abolitionist movements, even if they are not immediately recognized by white readers. Read from the perspective of Black Americans, in fact, Cather’s biblical allusions reveal heroes who triumphed over imperialist actors. These heroes persevered and triumphed by remaining true to their beliefs and heritage. Daniel and Joseph were not made better by slavery but succeeded because they maintained their Hebrew heritage in the face of obliteration and acculturation by the imperial order. When those orders tried to impose their will upon the two men, these humble slaves upended the imperialist order in their fidelity to their traditions and refusal to capitulate. In including these seemingly oblique biblical allusions in the printed novel, Cather maintains a thread of resistance throughout Sapphira and the Slave Girl that, although not so direct for her characters as it was in the unpublished manuscript, is one that contemporary Black readers would likely recognize.

Simply put, the printed novel is loaded with liberatory allusions. It may very well be that Cather was “willing to sacrifice the realism and verisimilitude of the individual characters and relationships in favor of the larger dramatic and aesthetic demands of her novel,” where the “realism and personhood of various characters must be subordinate to the narrative itself,” as Clere maintains (458). Or it may be that Cather felt the novel was more reflective of reality by omitting overt references to liberation. Cather’s biblical allusions illustrate a writer contending with the issues of Black liberation from slavery; she certainly thought about these moves and how best to represent that struggle throughout the composition of Sapphira. She seems also to have chosen the way Black Americans read scripture: against the grain, in ways hidden from white readers and interpreters of scripture, and toward oppressive aims. I wonder if Cather—an astute reader of the Bible—figured this out for herself, hit upon this approach by accident, from guilt, or perhaps gleaned such views from her acquaintance with Harlem Renaissance artists while she lived in New York City. In assessing Cather’s relation to Black American characters or contemporary issues, her biblical allusions in Sapphira should not be overlooked. Whether she intended to include them or not, Sapphira and the Slave Girl contains clear moments of identification with and, potentially, celebration of Black liberation theology.