From Cather Studies Volume 14

Willa Cather and Mari Sandoz: The Muse and the Story Catcher in the Capital City

For generations of ambitious young Nebraskans, all roads led to Lincoln. The capitol’s skyscraping golden dome, crowned with The Sower and visible for miles was—and remains—a range light for academics, scientists, artists, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and anyone fleeing the farm. Willa Cather (1873–1947) and Mari Sandoz (1896–1966) arrived before the dome’s completion, but it was in Lincoln, the capital city, that these two iconic Nebraska writers pursued higher education, encountered resistance, navigated the town’s matriarchal “blackball” caste system, and began to mold memory, the raw material of their art.

How did the small village of Lancaster, founded on a salt marsh two years after the Kansas-Nebraska Act, then rechristened “Lincoln” in 1867 (over the howling protests of Confederate sympathizers), influence Cather in fact and in fiction? Lincoln, self-proclaimed “Athens of the Plains,” was an early but formative dislocation for Cather. By 1890 she was far from breezy Red Cloud; Lincoln had a brand-new Old Guard that valued property, propriety, family-of-origin, and cash. Social inclusion, club membership, participation in the arts, writing credits—these objectives were attainable by invitation only. Intellectually sophisticated, uncommonly cosmopolitan, and outspoken, Cather ultimately succeeded at treading the fine line between authentic self-expression and the established social conventions of Lincoln’s university, Near South, and O Street elites. As the gifted, classically trained daughter of a respectable Virginia family, Cather passed. Her friends—Mary Letitia Jones, Katherine Weston, Mariel Gere, Louise Pound, Dorothy Canfield, and, in time, Edith Lewis—all passed.

Mari Sandoz did not pass. Malnourished, snow blind in one eye, running from an abusive marriage, Sandoz crash-landed in Lincoln with little more than an eighth-grade education and a Sand-hills teaching certificate. Regardless, she was determined to tell her own gritty version of northwestern Nebraska history, which she did in books like Old Jules, Slogum House, Crazy Horse, and Cheyenne Autumn. In her explosive 1939 novel Capital City, Sandoz declared the city of Lincoln (dubbed Franklin in the book) “Buffalo Bill’s prostitute,” compared smug Lincolnites to “a cluster of lice along the vein of a yellowing leaf,” and viciously lampooned its Depression-era civic leaders as fascists (1–7, 257). In one memorable scene, Sandoz gleefully killed off a thinly veiled knight of Ak-Sar-Ben in the men’s room—as she put it, with his “feet sticking out from under the door of the can” (21).[1] Capital City was banned or restricted in several Nebraska communities, including rival Omaha. In 1948 Sandoz’s name appeared on a list of communist and subversive writers compiled by the California legislature’s Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities (Stauffer 198). The backlash over Capital City resulted in death threats that drove Sandoz out of Lincoln for good.

And yet, despite their wildly differing aesthetic sensibilities, Cather and Sandoz led remarkably parallel lives. Cather was a generation older than Sandoz, but both writers lived through the final stages of Nebraska’s frontier history: Cather in Red Cloud, Sandoz in the rugged Sandhills. Each was the eldest of several siblings, born to fathers who were well-known Nebraska boosters and pioneers. Their crowded childhood homes were managed by distracted mothers and long-suffering maternal grandmothers who moved in to help keep house. As writers, both women dedicated their lives to crafting stories of the mythic West; they both loved and brooded over the plains. They both mined complicated and conflicted memories of youth and childhood to produce bittersweet, authentic stories of life on the American borderlands. In the end, they both quit Nebraska, moved east, and died in Manhattan.

In Lincoln, both women experienced critical turning points in their development as writers, but their reception and recognition in the capital—as daughters, as university students, and as emerging writers—could hardly have been more different. Their formative years in Lincoln and at the University of Nebraska helped determine the trajectory of their careers, launching Cather toward national and international prominence while consigning Sandoz to regional writer status. Sandoz’s work is still largely overlooked today. “The grandmothers of the town won’t have Mollie,” Sandoz wrote in Capital City, using yet another variant of her own name, “not those three old women who run it. [...] They won’t have an outsider, a newcomer. The honors have to go to what they call the good old families, at least two generations old” (12).

When Cather’s family of genteel, dislocated Virginians rolled into Catherton and Red Cloud, three generations strong, the shades of Willow Shade came with them. Cather’s colonial ancestors held their land grant from Lord Fairfax; they were among the first European settlers in the lush Shenandoah Valley. Cather’s maternal grandfather, William Lee Boak, and her great-grandfather, James Cather, had served simultaneously in the Virginia General Assembly. Of her comfortable and privileged childhood in Virginia, Cather would later drily comment that “people in good families were born good” (qtd. in Lee 26). Cather’s courtly father, Charles Fectigue Cather, and her strong-willed, patrician mother, Mary Virginia (“Jennie”) Boak Cather, had been “born good,” and Nebraska knew it. Like Lincoln, Red Cloud was located south of the Platte River, Nebraska’s ersatz Mason-Dixon Line. Although few enslaved persons were ever transported into the disputed Nebraska Territory, raw land in the southern half of the state attracted a distinct minority of settlers (often vocal Democrats) from Virginia, Missouri, and southern Ohio, particularly along the Kansas state line. Half of Nebraska’s territorial governors were natives of Kentucky or South Carolina. In the fall of 1883, Cather was a student at the sod schoolhouse in “New Virginia,” just south of Catherton. Meanwhile, in the booming capital, as Bernice Slote has noted, women with family backgrounds much like that of Cather’s mother “moved in, took out their white kid gloves, subscribed to Century, shipped in oysters frozen in blocks of ice, and tried to keep life very much as it had been in Ohio, New York, Illinois, or Virginia” (7).

According to historian Frederick Luebke, Lincoln was considered “more Protestant, Anglo-Saxon, clean and moral,” than immigrant-magnet Omaha and communities north and west (218). Although Omaha, the original territorial capital, ultimately lost a heated battle for the statehouse to “South Platters” in 1867, it remained the state’s commercial hub. Compared to Lincoln, Omaha was a cow town, plain and simple. It boasted stockyards, meatpackers, the Livestock Exchange, Missouri River landings, and the Union Pacific Railroad (Olson 118, 209–10). However, in Nebraska, unlike virtually every other state, Lincolnites consolidated power and influence by taking all the rest that was of importance—the capitol building, the prestigious land-grant university, the lucrative courts, government offices and agencies, the state hospital, and the penitentiary (Barrett 60). They even took the Nebraska State Historical Society and the Home for the Friendless. Silas Garber, founder of Red Cloud and the model for Captain Forrester in A Lost Lady, was elected governor in 1874, then reelected in 1876. Lawyers, bankers, investors, land brokers, and insurance agents, many of whom were friends or business associates of Cather’s affable father Charles, quickly set up shop. Eager to replicate the familiar pattern of civic life and leadership in their new western homes, prominent citizens and boosters quickly chartered business and fraternal organizations, women’s clubs, philanthropic institutions, lodges, secret societies, and academic groups. In Red Cloud, Charles Cather was repeatedly elected to leadership positions in city, county, and fraternal affairs. In 1888 he was elected venerable consul, manager, and delegate to Head Camp of the Modern Woodmen of America, forerunner of Omaha’s insurance giant, Woodmen of the World (“Modern Woodmen” 1). Charles Cather may not have been as rich or as driven as his Lincoln peers, but as a refined Virginian and one of Nebraska’s Old Settlers, he associated with a select set, as did his daughter. “She [Willa] came of a good cultured family,” one of Cather’s classmates noted, “and chose her friends of the cultured type” (Shively 141).

As in many (mid)western boomtowns and capitals, society in Lincoln stratified rapidly. The new brick-and-limestone “commercial blocks” of O Street represented the city’s best business address. Lincoln’s “O Street Gang,” as the city’s clannish first families, business leaders, and political power brokers eventually came to be known, jealously guarded access to the city for over half a century. Cather was clearly aware of their influence because she won their support and moved among them freely. To a 1918 Nebraska reader of My Ántonia, Jim Burden unmistakably confirms Lena Lingard’s impressive rise from barefoot hired girl to society dressmaker in one brief exchange: “You are quite comfortable here, aren’t you?” Lena says, looking around his room. “I live in Lincoln now, too, Jim. I’m in business for myself. I have a dressmaking shop in the Raleigh Block, out on O Street. I’ve made a real good start” (218). Cather did just that in the 1890s, when she quickly became the startling young arbiter of Lincoln’s bustling university, O Street, and theatrical scenes.

Timothy R. Mahoney’s groundbreaking spatial narrative, Gilded Age Plains City: The Great Sheedy Murder Trial and the Booster Ethos of Lincoln, Nebraska, provides unusual insight into the dynamic city of Lincoln (population fifty-five thousand) in 1891.[2] This was the year after Cather moved to Lincoln to attend the university’s preparatory Latin School and the same year the sensational John Sheedy murder trial electrified Nebraska. According to Mahoney, the social, moral, and political issues raised at the trial caused “profound worries about the integrity of the class, gender, and racial systems that had sustained Lincoln society for a generation” and “raised deep fears that other ‘poseurs’ and ‘charlatans’ might be living among them.” Mari Sandoz’s father, Old Jules, branded “the notorious Frenchman” by the Omaha Daily Bee on October 9, 1891, was just the sort of character many Lincolnites shunned on sight.

Mahoney’s spatial narrative explores the trial, the booster ethos of Lincoln in the 1890s, and its principal players “at the micro historical level of lived experience in a specific time and place,” contending that “space and the built environment of a city are not mere backdrops, backgrounds, or contexts in which events occurred. They play a central role in understanding the development of social and political order.” The spatial narrative contains a vast and deeply documented research base of primary materials, biographical narratives, and images that reflect the politics, culture, economy, and society of Cather’s Lincoln. It deconstructs relationships between Lincoln’s established business and university elites and members of the middle or working classes. Gilded Age Lincoln was a tumultuous town. In 1888, from his position with a bird’s-eye view atop a new five-story building on O Street, Thomas H. Hyde, president of the Lincoln News Company, described the chaotic street scene he saw below, where “the swelling, hurrying flood of animation, mingling with a world of commerce on wheels, crowded street cars, omnibuses, coaches and cabs, moves on,” he reported. In Lincoln, Hyde continued, “youth jostles age, poverty on foot stares Croesus in his carriage” (qtd. in Mahoney intro). It is interesting to note that Cather, when walking from her boardinghouse at Tenth and L Streets to the university, or from the university to dinner at the elegant Queen Anne or Painted Lady homes of her friends, had to cross through the heart of P Street’s “demimonde,” a ramshackle district of bars, brothels, and billiard halls. Traces of the demimonde may survive in Cather’s pool-shooting, cocktail-mixing heroine in “Tommy, the Unsentimental.” In the boisterous capital, high and low moved shoulder to shoulder: separate, unequal, and crossing paths but maintaining their own appointed spheres. Like Tommy, Cather was notable for friends who “were her father’s old business friends, elderly men who had seen a good deal of the world, and who were very proud and fond of Tommy” (6). When Cather and her mother traveled to Lincoln to select Cather’s boardinghouse residence, they stayed at the home of Robert Emmett Moore (Woodress 69), former mayor of Lincoln and future lieutenant governor of Nebraska. Jennie Cather, Willa’s formidable mother, must have been determined to secure safe and suitable living quarters for her teenage daughter. It’s also possible that she initiated social calls and introductions at this time.

University tuition was free in 1891, but the cost of sending a daughter to live in Lincoln and attend the university (for those families who would even entertain the idea) was significant. The estimated expense of $350 per year or $175 per semester (Manley 114) was the equivalent of $11,833 in 2023 dollars.[3] The price was prohibitive for most Nebraskans. It also sparked criticism. In 1889 one legislator declared that the university “was maintained by the poorest people of the state for the purpose of giving the rich man’s son a free education” (qtd. in Manley 109). Many of Cather’s female classmates were the daughters of prominent and well-educated Lincoln judges, legislators, businessmen, or bankers. There were no dormitories, so these young women walked to class and lived at home. Including her preparatory year at Latin School, Cather would spend five years living and boarding in Lincoln on her own.

In 1919, nearly twenty-five years after Cather’s graduation, the official Semi-Centennial Anniversary Book of the University of Nebraska, 1869–1919 made explicit the general expectations, both personal and professional, for the young women who had attended the University of Nebraska: What should be said about the thousands of women graduates of the University of Nebraska? Their highest contribution is that of home-builder. They are the mothers of many of the sons and daughters who have come and will come to the Alma Mater of their parents. As the wives of alumni, their contributions are interwoven with those of their husbands. They have followed their husbands into the missionary fields of China and Japan. They have worked side by side with them in their research and their publications; while those who have not trained their own sons and daughters have helped to train others. (Semi-Centennial 68)

Willa Cather had other ideas. In March 1891, while she was still a prep student, her impressive first essay was published by the Nebraska State Journal. In the fall of 1892, she became an associate editor of the Hesperian, the university’s leading student publication. The Hesperian would publish her earliest short stories. By the following year she had become managing editor. A fellow staff member recalled that “the Hesperian was Willa practically” (qtd. in Slote 12). On 5 November 1893 her pithy column on literature, local life, and traveling theater productions began to appear in the Sunday Journal. For this, for her “meat-axe” theater reviews, and for her later Courier articles, Cather was paid—usually one dollar per column (Woodress 84). Against long odds, she had turned semiprofessional. During the last two years of her college career, Cather was writing at a furious pace for pleasure and for profit. She was gaining remarkable skills, but it is unlikely that she was able to cover her living expenses without supplemental assistance from her family in Red Cloud. Soon after her graduation, Cather returned home, where she could live for free as she struggled to create a viable path to personal and financial independence. Although she continued traveling to Lincoln to write and to review theater, Cather quickly turned her attention to obtaining a university teaching position.

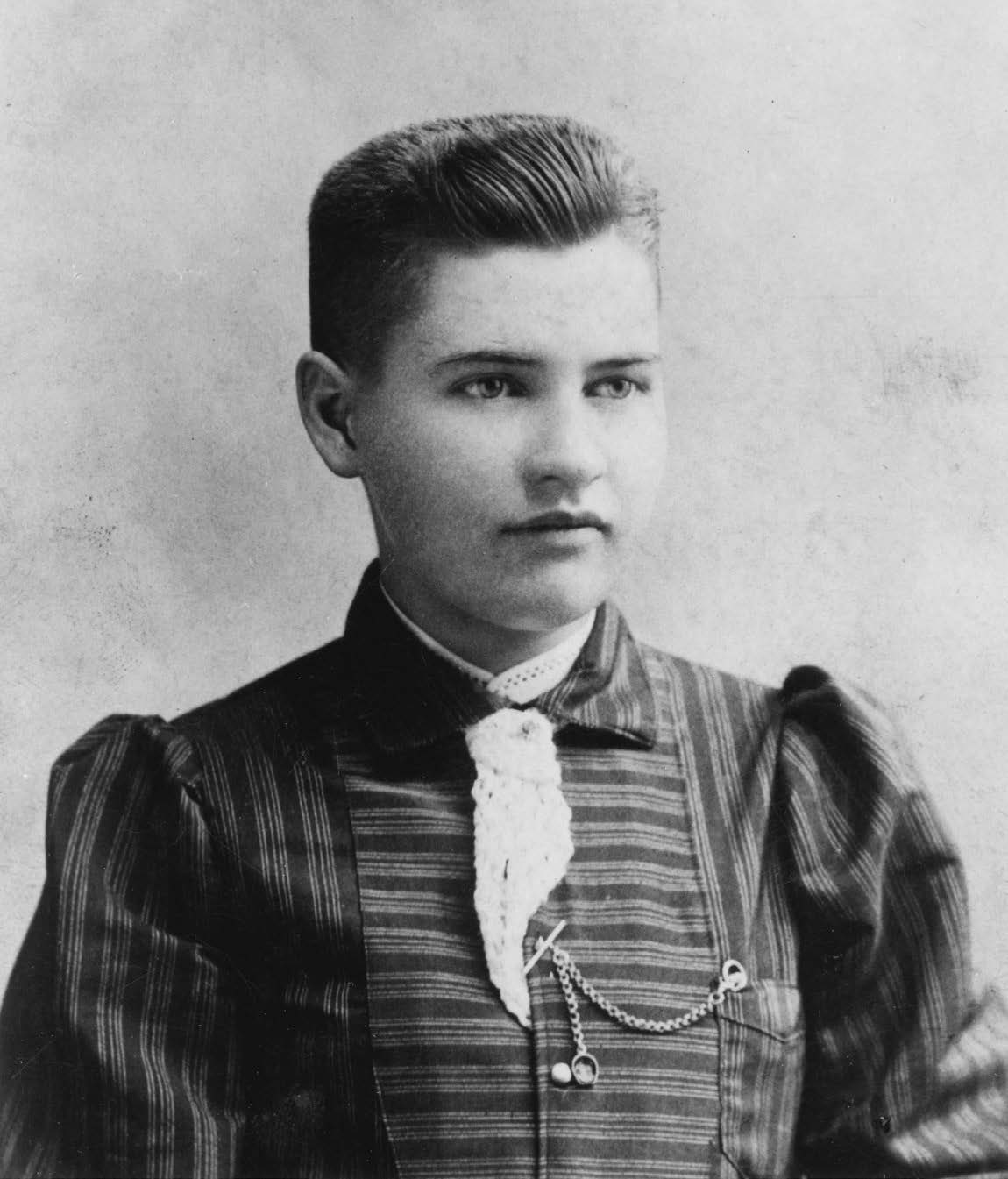

Cather’s university years seem more intriguing, collegial, and financially secure than she portrays them in her later writings and fiction. In 1891 the appearance of Willa Cather’s provocative alter ego, William Cather Jr. (would-be MD), on campus, sporting chopped hair and masculine-style clothing, should have triggered every wrought-iron lock on every Victorian door from Greek Row to O Street. But in Cather’s case it didn’t. Instead, Cather socialized as an equal with the sons and daughters of the wealthiest, best-known, and most politically connected families in the state: the Pounds, Geres, Westons, Moores, Harrises, Canfields, and others. Despite her unconventional and sometimes deliberately provocative appearance, from the time Cather arrived on campus she was received in the paneled libraries and Eastlake parlors of Lincoln’s “best” families like the prodigal daughter. She was one of theirs, and they were willing to protect, promote, advise, or defend her. “Willa always followed her own inclinations, anyway,” Mariel Gere told a reporter in 1924. “[S]he didn’t care much what other folks said or thought. She was always a little eccentric, but as she grew and went on through school, her notions seemed to change, and she became more like the other girls” (qtd. in Wyman 6). As late as 1950—six decades after Cather first arrived in Lincoln—Mariel Gere was still defending her friend against accusations of arrogance (“thinking so well of herself,” a cardinal sin in Nebraska), friendlessness, and cross-dressing (Hoover and Bohlke 10).

Fig. 9.1. Willa Cather at the time she entered the University of Nebraska as a

first-year student. Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–

Lincoln Libraries.

Fig. 9.1. Willa Cather at the time she entered the University of Nebraska as a

first-year student. Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–

Lincoln Libraries.

Mariel Gere would know; her mother played the decisive role in Cather’s grudging transformation. It is possible that Cather’s mannish appearance was tacitly accepted so long as she pursued her interest in the male-only fields of science and medicine. According to Dr. Julius Tyndale, an early mentor, Cather told him “she had always wanted to be a boy,” but she didn’t break “the last straw” until she wore boys’ clothing to a party at a private home, at which point Tyndale told her point-blank she had to be less conspicuous (Wyman 6).

In 1883 fifty-two young men were enrolled in the university’s new and controversial College of Medicine. Many professors and university administrators considered medical school “technical training” and thus incompatible with, and unworthy of, the university’s mission of classical education. Admittedly, the incoming medical students did little to endear themselves to the administration. After several Lincoln physicians declined to teach in campus classrooms and anatomy lessons were canceled due to a lack of cadavers, a few disappointed but enterprising medical students climbed on top of University Hall and scrawled CASH FOR STIFFS across the roof in lead paint. They then proceeded to outrage church-going Lincolnites by organizing body-snatching expeditions to rural cemeteries (Manley 95–98). In May 1887 the regents shut down the College of Medicine with a sigh of relief, but Cather would have known about the rowdy department and its well-publicized exploits; it may even have piqued her adolescent interest in vivisection, dissection, and rabble-rousing. As a child, Mari Sandoz also dreamed of becoming a doctor. A sympathetic former teacher recalled how Sandoz carried a little roll of rag bandages, needles, thread, and antiseptic with her everywhere. Regrettably, “she often had occasion to use them” (Cass).

Although Cather’s large family was not wealthy by Lincoln standards, it is unlikely that the cost of her education required serious financial sacrifices at home, at least not until 1893. In 1890 the Red Cloud Republican failed (taking Charles Cather’s investment with it), and he likely borrowed money to send Willa to Lincoln’s Latin School—where she promptly moved into the city’s best boardinghouse.[4] Cather could not live like a male student on campus, cutting costs by living in a cheap, overcrowded rooming house or “batching” it, as Will Owen Jones, Cather’s friend and editor, later reminisced about his college days (Semi-Centennial 42). Had she done so, her family would have lost face and she would have lost her reputation.

Classmate Edward Elliot remembered Willa Cather as “one of those more fortunate students” who did not have to work and therefore “had the benefit of time to give to extra-curricular matters” (Shively 124). Even the financial Panic of 1893 and the unprecedented drought of 1894—events that ruined thousands of families statewide—did not derail her studies. By 1895 Charles Cather was employed by Robert Emmett Moore, president of Lincoln’s Security Investment Company. After serving three terms in the state senate, Moore had just been elected lieutenant governor. His brother and business partner, John Huntington Moore, a former Red Cloud banker, was a close friend of the Cather family. Willa was a frequent visitor at Robert Moore’s turreted mansion on E Street. In 1921 Moore left an estate worth $2.5 million. Unlike Lincoln, in small-town Nebraska wealth and status might be respected, resented, or quietly acknowledged, but they were rarely on display; among other objections, flaunting was considered bad for business. “Father is a very modest man and he wants me to be modest,” Cather noted (qtd. in Bennett 27). Common courtesy was obligatory, but lifestyle differences could be enormous, especially in the privacy of the home.[5] In My Ántonia, Widow Steavens remarks that Ambrosch’s wedding gift to Ántonia, a set of plated silver, was “good enough for her station” (309), but for the Cathers of Webster County, weddings were an Old Dominion affair, subject to a very different set of expectations and etiquette. In 1896, when Cather took charge of her cousin’s wedding breakfast in Red Cloud—the Province of Siberia, as she liked to call it—she had fresh strawberries, tomatoes, and watercress shipped in from Chicago, in the dead of winter (Complete Letters #0022).

Although Cather may have preferred rumpled menswear, the many formal portraits of her from the period show her well dressed and crisply tailored. Fashion (like association) is a reliable indicator of social status and respectability in the 1880s and 1890s. Even in unceremonious Red Cloud, Willa Cather’s mother, Jennie, was fastidious in her dress, carrying parasols that matched her expensive ensembles. Compared to Judge Stephen and Laura Biddlecombe Pound’s family, however, the Cathers were barely keeping up appearances. In Cather’s well-known 16 June 1892 letter to Louise Pound—the letter in which Cather, utterly infatuated with Louise, admires her at a party—there is mention of Louise wearing her new “Worth Costume” (Complete Letters #0010). That’s not Woolworth’s; it can only be House of Worth, founded by Charles Worth, the most celebrated French couturier of the Gilded Age. Worth designs and bespoke copies were available in America at the time. They were coveted by high-ranking socialites, opera singers, and celebrated actresses in society bastions like Newport, New York, and Washington; they were works of art. Louise Pound, soon to pursue her doctorate degree at the University of Heidelberg, was turned out like Sarah Bernhardt or Consuelo Vanderbilt in her parents’ Nebraska home.

Cather could be imperious, but she was no snob. Her Hesperian fiction betrays uncomfortable ambivalence toward Lincoln society and her place in it. From the shallow, social-climbing sorority girls Cather mocked in “Daily Dialogues or, Cloakroom Conversation as Overheard by the Tired Listener” to her parody of Grand Tour Americans demanding pumpkin pie in Rome, Cather frequently skewered the behavior of her peers (Shively 93–108). In early short stories like “Peter,” “Lou, the Prophet,” and “The Clemency of the Court,” Cather’s sympathetic protagonists are loners, struggling farmers, or mistreated laborers. As Kelsey Squire demonstrates in “Legacy and Conflict: Willa Cather and the Spirit of the Western University,” Cather drew continually on her social and pedagogical experiences at the University of Nebraska in her later work, particularly My Ántonia, One of Ours, and The Professor’s House. Squire notes that Cather disparages “strategic social moves” like Jim Burden’s society marriage or Harris Maxey’s “feverish pursuit of social advantages and useful acquaintances” at university, as well as the commercialization of Tom Outland’s scientific legacy (250).

In her junior year, Cather turned her “meat-axe” on Roscoe Pound, declaring Louise’s brother a pretentious has-been, bore, and bully in her Hesperian column “Pastels in Prose.” It was too much; the backlash was public and likely coordinated. Classmate Ernest C. Ames, “fed up” with Cather’s “cruel, cynical, unjust and prejudiced criticism of everyone on the campus, students and profs,” sent a front-page retort to the Daily Nebraskan titled “Postals in Paste” (Shively 135). In the piece, published in the spring of 1894, he compared Cather to Louis XIV proclaiming “Moi, le Roi,” and suggested Cather wanted all her benighted classmates sent down with “Bohunkus” to ignominious Doane College (Ames 1). Reigning clubwoman Laura Biddlecombe Pound also retaliated. She closed her doors to Willa Cather; Cather was not to be received. Uncharacteristically, other Lincoln matriarchs, including Mariel Clapham Gere and Flavia Canfield, did not follow suit but apparently sought to mend Cather’s costly breach of manners (Krohn 74). Willa Cather held her own. Mari Sandoz would not be so fortunate.

The Geres proved particularly influential in Cather’s university life and budding career. Charles H. Gere, publisher of the Nebraska State Journal, had served as a state senator in the first legislature, as private secretary to Governor David Butler, as chairman of the State Republican Committee, and as president of the University of Nebraska Board of Regents. In a heartfelt 1912 letter to Mariel Gere, Cather recalled her first invitation to dine at the Geres’ welcoming home, soon after her arrival in Lincoln. This type of invitation was rarely spontaneous; “good families” offered hospitality to their peers after receiving personal requests or letters of introduction. Willa Cather was duly vetted and approved; in fact, she captivated the Yankee Geres. In a 24 April 1912 letter to Mariel Gere, she recalled that Charles Gere had told her she looked like “Sadie Harris” (Complete Letters #0223). (“Sadie” was Sarah Butler Harris, the outspoken social page editor and suffragist who held court from her Italianate home on K Street; in 1895 she hired Cather as associate editor of the Courier.) In the same letter, Cather memorialized the kindness, persuasiveness, and gentle humor of Mrs. Gere. No one else, Cather claimed, could have convinced her to grow out her hair, and she particularly appreciated the fact Mrs. Gere did not scold young people (presumably a reference to Cather’s own mother). Evidently, Cather felt constant pressure over her unwillingness to conform. In a 23 February 1913 letter to her aunt Frances Smith Cather, Cather expressed her relief at finally overcoming her childhood shyness and, in a phrase that flies off the page, her “queer fears” around her family. As a child, she says, she felt that all of them, even her father, wanted to change her, to make her over, and she most emphatically did not want to be made over (Complete Letters #0245).

Cather’s appearance changed dramatically over the course of five years in the capital. As she entered Lincoln society and took the university by storm, the vestiges (even the proud signature) of William Cather Jr. slowly but inevitably disappeared. By graduation day, Cather seems to have made a new personal and social calculus, based on hard reality. Biographer Hermione Lee detects something potentially “camp” in Cather’s well-known graduation portrait (44), the photograph depicting Cather in full debutante array (ivory net over ivory satin ballgown, leg-o’-mutton sleeves, and white kid gloves), her titian hair piled on her head, her gaze intense and inscrutable. Lee may be correct. But Cather is also the very image of high society’s unattainable and independent Gibson Girl, the New Woman who has seen the future and decided (despite the odds) that it is female.[6] This is a socialite’s photo for public consumption. Significantly, in March 1895, during her expensive week of grand opera in Chicago, Cather slipped away to have two entirely different graduation portraits made at William McKenzie Morrison’s studio: one in severe black cap and gown, the other in her fur-lined opera cloak. Morrison was the leading theatrical photographer of his day, specializing in cabinet cards of celebrated actors and opera singers.

Fig. 9.2. Willa Cather’s university graduation portrait, 1895. Archives and

Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.

Fig. 9.2. Willa Cather’s university graduation portrait, 1895. Archives and

Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.

For Cather, the risks, the stakes, and the rewards of social acceptance were sky high. In Lincoln, Cather was not an outsider trying to write her way in. She was an insider trying to write her way out: “For I shall be the first, if I live, to bring the Muse into my country” (My Ántonia 264, emphasis added). Just as Jim Burden ponders Virgil’s line in My Ántonia, countless Cather readers have reflected on the line’s significance to Cather and to her work. Cather seems well aware that she could not live to achieve her full potential as an artist in Nebraska. She needed and longed for a wider world. Yet to many readers, Cather did not bring the muse; Cather is the muse. She turned the prairie into living art. She lives in her work, she is virtually embodied there, and that body of work remains both an object of beauty and desire and a source of inspiration. Clearly, writing for the Hesperian and the Lincoln newspapers had ignited her imagination and ambition. She had acquired readers and a byline. Ultimately, Cather cannot “bring the Muse” without the support and approbation of the lifelong friends and advocates she had acquired in Lincoln. Upon graduation, Cather faced the same three options as nearly all her other female classmates: she could marry and take her place in society, she could live with her family and teach, or she could close her eyes and pray for a miracle.

Cather’s “miraculous” leap from Red Cloud to Pittsburgh in 1896 was the combined result of her precocious talent, hard work, and her powerful Lincoln connections. James Axtell could have hired any established East Coast writer to edit his new magazine, Home Monthly. Instead, he bet on the brilliant Nebraskan. She must have been recommended by friends Charles Gere and Nebraska State Journal editor Will Owen Jones. In addition, she had a growing reputation for excellence among other Nebraska journalists. A columnist for the Omaha World-Herald wrote, “If there is a woman in Nebraska who is destined to win a reputation for herself, that woman is Willa Cather.” The Beatrice Weekly Express described her as “a young woman who is rapidly achieving a western reputation, and who will soon have a national reputation. She is one of the ablest writers and critics in the country, and she is improving every week” (qtd. in Slote 27).

When she arrived in Pittsburgh, Cather spent several weeks living in the Axtells’ home, as an equal, as a guest. James Axtell’s wife, Nellie Minor Axtell, had lifelong family connections in Lincoln, where she was a frequent visitor. She was the niece of Nebraska land magnate Rolla O. Phillips, whom Cather also knew. Phillips’s Richardsonian Romanesque mansion, “The Castle,” with its enormous carriage house, fifteen fireplaces, and third-floor ballroom, is a Lincoln landmark. Writing from Pittsburgh on 13 July 1896, Cather told Mariel Clapham Gere she intended to ask “Captain Phillips” for a personal favor (Complete Letters #0026). Cather needed a photo of Mary Baird Bryan for her article “Two Women the World Is Watching.” She got it, too, “[f]or,” as Cather deadpanned in the article itself, “there is such a thing as society, even in Nebraska” (4–5).

By the time Cather left Red Cloud for Pittsburgh, for France, for New York, for Grand Manan, her experiences had made her far more self-protective, self-possessed, and intellectually fiery than virtually all her hometown friends and readers. Cather feared few things, but as she later confided to Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, she feared dying in a Nebraska cornfield, under a windmill, where there was no place to hide (Sergeant 49). And yet, in Lincoln, as her Hesperian fiction suggests, it appears that Cather was already casting that long look back over her shoulder. She was beginning to render her past. These were heady—but wistful—years for Cather, a time of intense and inescapable social contrasts. It was a time when nostalgia quickened and, in the words of Jim Burden, “I suddenly found myself thinking of the places and people of my own infinitesimal past. They stood out strengthened and simplified now, like the image of the plough against the sun” (My Ántonia 262).

In the years to come, Cather would continue to think—and sometimes to write—about her Nebraska home. In 1913 O Pioneers!, the book she considered her “real” first novel (actually her second, preceded by Alexander’s Bridge), was published. Writing the book had engaged her tremendously, “because it had to do with a kind of country I loved” and was “about old neighbors, once very dear.” As she wrote the book, she knew that “the novel of the soil” was unfashionable. Remembering a New York critic’s comment that “I simply don’t give a damn about what happens in Nebraska,” she expected that the novel would never be published (“My First Novels” 964). But it was, to enthusiastic reviews. The Boston Evening Transcript, for example, reported “that with O Pioneers! Cather introduced a new kind of story and a new part of the country into American fiction, commending especially Cather’s disclosure of the splendid resources of the immigrant population and the changing face of the country” (qtd. in Stouck 295–96). Five years later, when My Ántonia appeared, reviews were even more enthusiastic, but they did not emphasize the newness of the novel’s Nebraska country and characters. Clearly, Cather had already established the muse in her Nebraska home country. According to David Stouck, Cather “had achieved what Virgil wrote of in those lines that she quoted in My Ántonia. . . . O Pioneers! was certainly the novel in which she first brought the muse into her country” (302). And “her country” included not only the rural, small-town world of Red Cloud and Webster County but also Lincoln and its university, which figure so importantly in My Ántonia and One of Ours.

Mari Sandoz, Cather’s closest literary counterpart, didn’t bring the muse to Hay Springs, Nebraska, but what she lacked in sheer artistry she made up for in incendiary bomb–throwing. Her graphic portraits of homesteading in the Nebraska Sandhills exposed the dark cartoons hidden beneath Cather’s epic pastoral landscapes. “The underprivileged child,” Sandoz later explained, “if he becomes a writer, becomes a writer who is interested in social justice, and destruction of discrimination between economic levels, between nationalist levels, between color levels and so on” (Stauffer, Mari Sandoz 5).

Marie Susette Sandoz (“Mari” approximated her family’s French pronunciation, MAHR-ree) was born by the Running Water of the Niobrara River to Swiss immigrant Jules Ami Sandoz and his desperately unhappy fourth wife, Mary Fehr Sandoz, both of whom worked their eldest daughter like the hired girl’s hired girl from an early age. The head manuscript reader at McClure’s Magazine once told Edith Lewis that if Willa Cather had been a scrubwoman, she would have scrubbed much harder than all the other scrubwomen (Lewis 30); Mari Sandoz was a scrubwoman. She scrubbed floors, sweat-drenched work shirts, greasy iron pots, and a long line of babies. Northwestern Nebraska was arid cattle country, the last region of the state to develop. In 1910 the living conditions in the Panhandle were far more primitive and isolating than Cather’s Divide in 1880. At the age of eleven, Mari served as her mother’s midwife and helped deliver her sister Flora.

Old Jules Sandoz was a legend among the Kinkaid homesteaders of western Nebraska. Intelligent, foul-tempered, and fearless, Old Jules considered the settlement and development of the Sandhills country his life’s mission. Utilizing an early form of chain migration, he was the region’s principal land locator, scouting homesteads for late-arriving immigrants. He was the Sandhills’ greatest booster and a crack rifleman, famous for taking potshots at his neighbors. When Old Jules served as postmaster, his tumbledown frame house—Mari called it “hot as an iron bucket in the sun”—was the community’s central meeting place (Sandhill Sundays 8). Old Jules beat all four of his wives, all six of his children, and most of his horses. He was also a master horticulturalist whose vineyards and orchards made the Sandhills bloom. Unlike most of his neighbors, Jules Sandoz had made good friends and hunting partners on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations. Mari interacted with tribe members from an early age, along with ranchers, farmers, magical water dowsers, traveling musicians, and the state penitentiary parolee her father boarded for cheap labor, despite his prior conviction for “criminal intercourse with a little girl three years old” (Old Jules 271).

After supper and dish duty, Old Jules’s hungry daughter spent her evenings crouched on a crate behind the woodstove, “story-catching,” in her words, her father’s tales of range wars, the dispossession of the Cheyenne and the Lakota peoples, and the early settlement of western Nebraska. “In my childhood,” she later wrote, “old trappers and Indian traders or their breed descendants still came to visit around our fire on the Niobrara River. ... The old-timers talked long and late hours about those days and the earlier years” (Cheyenne Autumn xi). The oral tradition would figure strongly in all her work. (Interestingly, Cather is said to have hidden under a quilting frame at Willow Shade, listening to her elders and absorbing the material she would later transform into Sapphira and the Slave Girl [Lewis 10].)

Mari spoke French and German with her parents until she was finally allowed to attend school at the age of eight. When she was ten, the Omaha Daily News published a story she had secretly submitted for its children’s page. Her outraged father responded by locking her in the pitch-black cellar with the bull snakes and the mice (Stauffer, Letters 135). Mari would prove as indomitable as Old Jules. As she learned to read, Sandoz (like Cather) sought out sympathetic neighbors who were willing to lend her books. She developed a particular fondness for Thomas Hardy. In Hardy, she claimed, she found life as she saw it about her. So life was like that everywhere, she decided, and that was best to know (Old Jules 340). “Hardy and [Joseph] Conrad fit the sandhills better than any other writers I know,” she later explained. “There is in their work always an overshadowing sense of the futility in life. This is revealed in their novels as it was revealed in the tragic, desperate lives of the settlers whom my father brought to Nebraska” (qtd. in Holtz 41). Sandoz was still in her teens when she began teaching in rural schools, married a local rancher to escape her father’s house, and began to write in earnest.

When Mari Sandoz Macumber finally fled the Sandhills for Lincoln in 1919, not long after the publication of Cather’s My Ántonia, she had no money, no husband (her divorce from Wray Macumber for “extreme mental cruelty” was socially stigmatizing), no introductions, and no connections. Her “drab, mismatched, and often threadbare clothing” immediately signaled her status as an impoverished girl from the outstate (Switzer 111). Worse, her father’s reputation for eccentricity, lawsuits, gun violence, and pro-German, antiestablishment, anti-everything statements preceded her. “You know I consider writers and artists the maggots of society,” Old Jules informed his daughter in 1926 (qtd. in Stauffer, Letters 81). In Lincoln, Sandoz cleaned houses, trained as a stenographer, worked at a local drug company stuffing pill capsules at the rate of twenty-five cents per thousand, took business classes by day, and wrote by night. She was probably exaggerating only slightly when she explained how she finally enrolled in the university’s Teachers College as an “Adult Special”: “I came to Lincoln, sat around in the anterooms of various deans for two weeks between conferences with advisors who insisted that I must go to high school. Finally bushy-haired Dean Sealock got tired of me and said, ‘Well, you can’t do any more than fail—’ and registered me” (Sandhill Sundays 156).

Fig. 9.3. Mari Sandoz’s parents, Old Jules and Mary Fehr Sandoz. Nebraska State

Historical Society Photograph Collections.

Fig. 9.3. Mari Sandoz’s parents, Old Jules and Mary Fehr Sandoz. Nebraska State

Historical Society Photograph Collections.

After Sandoz gate-crashed the university, she quickly excelled. As one of “Lowry Wimberly’s Boys,” she was in the vanguard of New Regionalism in American literature. Her short story “The Vine” appeared in Wimberly’s first issue of Prairie Schooner. Louise Pound, by this time one of the nation’s most distinguished professors of linguistics and folklore, also recognized Sandoz’s intelligence and mentored her raw talent. It was Pound who urged Sandoz not to compromise her authentic western dialect and idioms to suit New York editors. Sandoz’s “authenticity,” however, did little to advance her career in Lincoln. According to Mari’s sister Caroline Sandoz Pifer, Louise Pound introduced Mari “to many fine homes and ... defend[ed] her right to expression in her own way” (Pifer 62). It didn’t work, and the feeling was mutual. “Lincoln treated Mari like a cowgirl in their china shop,” Lincoln friend Sally Johnson Ketcham recalled in an interview. “They didn’t like her style or her subjects; she was decades ahead of her time.”[7]

Influential reporter Eleanor Hinman, to whom Willa Cather granted a rare and

lengthy interview in 1921, was a close friend of and advocate for Sandoz. Hinman

and Sandoz traveled together frequently, researching Native history, collecting

documents, and interviewing tribe members on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud

Reservations. Sandoz also attracted the attention of H. L. Mencken, who shared her

scorn of the “booboisie,” but as the Great Depression deepened and national

editorial rejections kept rolling in, Sandoz returned to the Sandhills in despair.

Sandoz could be as irascible as Cather. She vented her frustration and bitterness

in a 1933 letter to Hinman: My dear Eleanor:

Will you

please go to Hell?

If I’m tired and disgusted and want to lay down with

my face in the sand, please remember that sand is plentiful and the face is,

after all, mine. . . . I have made no secret of my opinion that Lincoln is the

last word in decadent, middle class towns, sterile, deadening. Only by a

conscious defensiveness did I exist there at all. While the sandhillers are

equally antagonistic to the creative mind they at least are not superior or

patronizing about it; do not set themselves up as beings of supreme culture.

They openly consider me an amusing fool but assume no responsibility for my

reformation, which, incidentally, is something. (Stauffer, Letters 59)

Fig. 9.4. Mari Sandoz as a young writer in Lincoln. Nebraska State Historical

Society Photograph Collections.

Fig. 9.4. Mari Sandoz as a young writer in Lincoln. Nebraska State Historical

Society Photograph Collections.

It wasn’t long before Sandoz tired of the antagonistic Sandhillers and returned to the antagonistic Lincolnites, determined to write history. Ever the dutiful child, Sandoz wrote Old Jules, her breakout biography, only because it was her father’s deathbed request. Just before the book’s acceptance, but after fourteen rejections, she hauled another seventy manuscripts into the backyard of her fifteen-dollar-a-month Lincoln apartment, dumped them in a washtub, and set them on fire, literally cremating youth (Stauffer, Sandoz, Story Catcher 88).

Old Jules was a sensation. “Wouldn’t Old Jules snort if he knew that his story won the $5,000 Atlantic Monthly Press prize?” Sandoz wrote to her mother incredulously (Stauffer, Letters 84). However, no amount of critical acclaim could persuade many Nebraskans to embrace Sandoz’s unpopular, unromantic, and increasingly political stories of pioneer life as she herself had lived it. One sly reviewer of Sandoz’s second novel, Slogum House, summarized the general objections: “Instead of the usual pious portrait of god-fearing Methodists who voted the Republican ticket straight, and who spent their days plowing the virgin soil and killing grasshoppers, or baking cornbread and rocking the cradle in a glow of self-sacrificial ardor for making the state safe for democracy, Mari Sandoz has given us a family of roaring, bawdy cut-throats whose passionate desire for personal gain, and unscrupulous means of getting it, are only [the] exaggerated overflowing of the uncontrolled red blood that must have run in the veins of many of the men who made our state” (Kauffman). Slogum House was censored by the mayor of Omaha, who labeled it “unnecessarily lewd” and “revealingly vulgar” (Woerner). Sandoz’s next novel, Capital City, exposed O Street corruption, homegrown fascism, back-alley abortion, drug deals, and unjustified police raids on boys who “wore silk panties” (Capital City 149). Horrified Lincolnites read it (often correctly) as a roman à clef. Sociologist Michael R. Hill studied and taught the allegorical novel as “a sociologically-grounded thought experiment” (38).

Today Sandoz’s astonishing body of work, as meticulously researched as Cather’s but with its emphasis on land use, water rights, Native dispossession, women’s history, ethnic and minority communities, and the legacy of conquest, reads like some radical precursor of modern New Western historians like Glenda Riley and Patricia Nelson Limerick. Historian Betsy Downey explores this topic in depth in “‘She Does Not Write Like a Historian’: Mari Sandoz and the Old and New Western History”: “When Mari Sandoz’s The Cattlemen was published in 1958 a reviewer for The Christian Science Monitor commented that Sandoz ‘does not write like a woman.’ He admitted that his observation was ‘not all compliment.’ Reviewer Horace Reynolds might well have said ‘Sandoz does not write like a historian.’ Such re-phrasing, with its implications of both compliment and criticism, is a good place to begin examining Sandoz as historian” (9).

Sandoz never fit comfortably into the arena of western writers or western historians. Her writing style was an idiosyncratic hybrid: too florid for history, too staccato for literature. Sandoz’s authentic and distinctive western voice set her apart, as did her exhaustive primary research and her attempts to reconstruct Native dialogue and figures of speech. Vine Deloria Jr., author of Custer Died for Your Sins and a well-known activist and preeminent member of the Standing Rock Sioux, held Sandoz in the highest regard. Deloria read Sandoz’s works after her death, but of Crazy Horse he wrote, [At first] I was a little offended that a non-Sioux had written a biography of one of the legendary personalities of my tribe. Surely, I thought, she would know little of the nuances of meaning that characterize Indian communities ... [but] Mari Sandoz had presented a masterful and wholly authentic account of the struggle for the northern plains. ... I was stunned at the wealth of detail contained in each line of text—material that must have come from her conversations over time with a large number of elders, filed then in some great and efficient memory bank, and later skillfully woven into a chronicle of the times that overflows with authenticity. (Deloria, introduction vi)

Cather and Sandoz never met. In 1931 Sandoz sent a letter to Cather praising Shadows on the Rock. “Shadows on the Rock becomes a part of the life the reader lives, not for the short span of the reading but for his always. May I thank you for the rare experience?” (Stauffer, Letters 27). Cather replied with her standard one-line acknowledgment of the letter’s receipt. In 1944 Jean Speiser of Life magazine wrote to Cather proposing a joint photo essay based on My Ántonia and Red Cloud. Appalled, Cather suggested substituting Sandoz’s Old Jules and western Nebraska instead. Cather told Carrie Miner Sherwood in November 1944 that the switch would save her embarrassment and would likely please Sandoz who, Cather had heard, was not averse to any amount of personal publicity (Complete Letters #1678). Cather’s comment wasn’t really fair or true. Sandoz was proud, generous, and easily hurt. She wanted what Cather wanted; she wanted recognition.

Although Sandoz considered Sapphira and the Slave Girl surprisingly “thin” (Stauffer, Letters 180), she revered Cather and her prairie novels, describing Cather’s luminous prose as like “sunlight on a swale” (Love Song 227). In 1959 Sandoz traveled to Red Cloud, where she met with Mildred Bennett and discussed Bennett’s early work on the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial, calling it “so much more important than anyone but you can see now” (Stauffer, Letters 346). Sandoz spent several years working at the Nebraska State Historical Society, preserving and adding research materials to history files ranging from “Bohemians in Nebraska” to the 1819 military post Fort Atkinson.

For Sandoz, recognition arrived with an honorary doctorate from the University of Nebraska in 1950. She went on to win a John Newbery Honor Medal in 1958 and the Western Writers of America’s Spur Award in 1963. In 1954 she received the Distinguished Achievement Award of the Native Sons and Daughters of Nebraska. The Mari Sandoz High Plains Heritage Center in Chadron is dedicated to her legacy, and with the publication of the first volume of the Sandoz Studies series (from the University of Nebraska Press, in July 2019), an important reevaluation of her work is underway.

After the publication of Old Jules, Sandoz responded to one disoriented reader’s question: “Have there been two strikingly different pioneer Nebraskas?” In her response, Sandoz differentiated between the comparatively settled environments of Willa Cather’s lyrical prairie novels and the make-or-break frontier farm- and ranchsteads depicted in Old Jules. According to one scholar, “The problem [for pioneers] was what one finds so superbly portrayed in My Ántonia and O Pioneers!—the problem of adjustment rather than one of staying at all at any price” (Holtz 42). The contrast was particularly stark for those who, like Sandoz and her family, could not afford to leave or were too stubborn to go.

Fig. 9.5. Mari Sandoz frequently returned to Lincoln to conduct research at the

Nebraska State Historical Society (shown in background). Nebraska State

Historical Society Photograph Collections.

Fig. 9.5. Mari Sandoz frequently returned to Lincoln to conduct research at the

Nebraska State Historical Society (shown in background). Nebraska State

Historical Society Photograph Collections.

Sandoz’s comment still resonates. In Becoming Willa Cather, Daryl Palmer considers the importance of Sandy Point, Cather’s make-believe town, in the development of her creative and territorial imaginations (20–23). Sandy Point, a place Cather often returned to in her mind, was a tidy, well-ordered country town. It boasted a wide Main Street lined with homes, offices, and shops. Cather served as mayor and news editor. In effect, it was her own personal parish. When Sandoz stood in the doorway of her father’s house as a child and surveyed the world beyond the bleak cattle fence, she said she saw Jötunheim, the land of capricious gods and giants: “Out of this almost mythical land, so apparently monotonous, so passionless, came wondrous and fearful tales” (Sandhill Sundays 24). To read the works of Cather and Sandoz side by side, especially My Ántonia and Old Jules, two books that draw on such similar material, is to engage in a tale of two conflicting and conflicted Nebraskas. Each informs and explicates the other. Together they provide human dimension and historical context for Cather’s and Sandoz’s pivotal years as young, evolving writers, for the Lincoln of their past, and for their strangely parallel yet nonintersecting worlds.