From Cather Studies Volume 14

Back to Virginia: “Weevily Wheat,” My Ántonia, and Sapphira and the Slave Girl

Willa Cather makes it easy for readers (and scholars) to give little attention to the song “Weevily Wheat” in My Ántonia. Cather places the verse in the pleasant kitchen of the Harling house; here daily life is filled with laughter, cleanliness, playful children, music, and good food. A happy Ántonia mixes a cake as the children, Jim Burden and the young Harlings, “were singing rhymes to tease Ántonia”:

I won’t have none of your weevily wheat, And I won’t have none of your barley, But I’ll take a measure of fine white flour, To bake a cake for Charley. (154)[1]

The “Weevily Wheat” moment contains multiple unspoken, sometimes concealed, connections to Virginia, particularly and surprisingly to Black American culture. The song—overlooked, nondescript, seemingly innocent—exemplifies the depths of Cather’s Virginia heritage and the cultural cross-pollinations prevalent in her work.

Bernice Slote notes that in Sapphira and the Slave Girl “a lifetime load of unwritten, cancelled Virginias, comes back across the prairies to both beginnings, the life and the art” (112). Slote’s statement still resonates, but two International Willa Cather Seminars in Virginia and over two dozen South-centric essays later we have become increasingly aware that many of Cather’s Virginia memories were written as much as they were “cancelled,” and they appear, sometimes clearly but often clouded, in much of her writing before Sapphira. Ann Romines notes the “complicated legacy of Virginia memories” while arguing “that much of Cather’s best fiction before her specifically Southern novel of 1940 [Sapphira] is, on some level, engaged with the problem of how to remember and to render the South” (“Admiring” 279). In particular, Romines points out that “the South surfaces in My Ántonia through Jim Burden’s early memories and the Virginia landscape of his dreams and in the troubling inset story of Blind d’Arnault, an African American artist who was born a slave” (279). I argue here that “Weevily Wheat” carries compelling messages about Cather’s conflicted relationship with the South and the ways she wrote about Black Americans.

My analysis seeks to provide an affirmative answer to the question posed by Anne Goodwyn Jones in “Displacing Dixie: The Southern Subtext in My Ántonia”: “Can we ... find traces of the South troubling the Midwestern terrain of My Ántonia?” (89). Jones locates such traces in the d’Arnault episode of course but also in Jim’s relationships with the Shimerdas, his ideas of male heroism, and his ongoing tensions with white southern masculinity. Elizabeth Ammons, in “My Ántonia and African American Art,” concludes that “[Cather’s] novel is deeply indebted to and shaped by African American music” (59). Ammons concentrates her perceptive analysis on Blind d’Arnault, the most significant presentation of a Black American musician in the Cather canon. While d’Arnault represents the most intentional and self-aware (though neither fully intentional nor fully aware) such portrait outside Virginia, ghosts of a Black American musical presence in the novel are also significant.[2] “Weevily Wheat” represents such a ghost, a moment whose Blackness has been unknown, ignored, and concealed. Furthermore, the reality of weevil-infected wheat and the associated metaphorical, signifying meanings communicate important aspects of the slave experience in the United States, expressing both the inherent unfairness of slavery and the strength of enslaved people.

The lyrics Cather includes are the chorus to a longer song, popular in the nineteenth century and with wide geographic and ethnic distribution. (Some of the many variants change the “Weevily Wheat” chorus to a verse; others, under titles like “Charley over the Water” or “Charley, He’s a Dandy,” eliminate it and emphasize Charley as a ladies’ man.) The lyrics vary considerably depending on such factors as geography, culture, and occasion. Found in collections of slave songs and Appalachian backcountry music but also in compilations of Irish and Scottish American folksongs, Wyoming ranch songs, pioneer songs of Minnesota, Indiana play-party songs, and more, the song’s popularity continued in the twentieth century, when it appears in the writings of iconic folk music collectors John and Alan Lomax, in musical scores by Peggy Seeger, in twenty-six entries in the Checklist of Recorded Songs in the English Language in the Library of Congress, in over a dozen tapes and records in the Library of Congress, and in perhaps the best-known collection of American folk music, Carl Sandburg’s The American Songbag. Hamlin Garland drew on its popularity in his short story “The Sociable at Dudley’s: Dancing the ‘Weevily Wheat’” from Prairie Folks, and Laura Ingalls Wilder memorably captured its power in On the Banks of Plum Creek when Pa Ingalls sings and plays “Weevily Wheat” on his fiddle in a climactic Christmas Eve moment joyfully celebrating his safe return after being lost in a blizzard. YouTube videos and online curriculum guides teach contemporary students to sing and dance “Weevily Wheat.” The song’s popularity suggests an influential cultural artifact grounded in family, neighborhood fun, and the midwestern pioneer experience. And so it appears in My Ántonia. Cather’s song choice, however, carries and conceals meanings that are often at odds with these assumptions.

There is nothing obvious, neither textually nor contextually, in the “Weevily Wheat” incident in My Ántonia to connect it to Virginia or to anything involving Black Americans. The song and its coded language were nevertheless important to nineteenth-century Black Americans in terms of entertainment, metaphorical meanings, and suggestions of protest. The song’s obvious characteristics—its subject of wheat and its genre of folk singing and dancing—provide a starting point for establishing a link to slave life. Wheat was an important crop in nineteenth-century Virginia, and it was subject to pests such as weevils. Before Cather knew the wheat fields of the Midwest, she knew the cycle of planting and reaping in Virginia, and she knew wheat as the source of grain for mills, including those her family had operated. Wheat was the largest crop in Frederick County, Virginia, home of the Cather family and the primary setting of Sapphira (Romines, explanatory notes 407–8, 432–33, 456, 500). As in the novel, Black Americans worked with wheat in the fields, the mills, and the kitchens, and wheat was a common subject of popular songs. Singing and dancing are of course universal to virtually all groups, including enslaved Black Americans. Lawrence W. Levine notes the widespread presence of music and dance among slaves (15), a fact Cather acknowledges in Sapphira, even given the relatively small population of slaves at the Mill Farm and in the Back Creek region. In that last Cather novel, the singing of Lizzie and Bluebell is much admired, and Tansy Dave “used to play for the darkies to dance on the hard-packed earth in the backyard” (204). Romines documents that “[d]ances on Saturday nights and special occasions were common on plantations throughout the South” (Explanatory notes 497). The musicality of Black Americans is also present in My Ántonia through visiting “negro minstrel troupes” (153) and Blind d’Arnault’s capacity to perceive the hired girls dancing in the kitchen as well as his ability to “draw the dance music out of [the piano]” (185).

In particular, versions of “Weevily Wheat” are prevalent in compilations of the music of Virginia and the rest of the South, and it is common in accounts of Black American music. Even though folk music was rarely written down, as early as 1868 “Weevily Wheat” was documented by John Mason Brown in “Songs of the Slave”: “who could hear, without a responsive tapping of the foot and unbending of the wrinkled brow, ‘I won’t have none of your weevily wheat / I won’t have none of your barley’?” (619). In his important collection Negro Folk Rhymes: Wise and Otherwise, Thomas Talley includes a common “Weevily Wheat” variant that discards the negative weevils and includes several fun verses emphasizing the dandy Charley and his appeals to women. The Virginia Folklore Index in the Archive of Folk Song at the Library of Congress includes eleven listings of recordings (index in Folder 13; recordings in Folders 6, 7, 10). The Gordon Manuscripts of the American Folk-Song Collection include two versions of “Weevily Wheat” (item 2603, vol. 9; item 3387, vol. 11) contributed by B. Clay Middleton, who notably collected folk material from Loudoun County, Virginia, an important place in Sapphira and well known to the Cather family. (While this archival material was recorded in the twentieth century, notations make clear that the song is part of a long-standing folk tradition.) “Weevily Wheat” was also popular in more mountainous regions of Virginia, places like Timber Ridge in Sapphira. Sandburg counts “Weevily Wheat” among the songs of pioneers who “left their homes to take up life in the Alleghenies and to spread westward” (161). John and Alan Lomax note that “‘Weevily Wheat’ has been enjoyed at play parties in backwoods districts in every part of the country” (xxxvi). Considerable cultural exchange occurred between Black workers and their white masters and fellow workers, a point affirmed by Levine: “black slaves engaged in widespread musical exchanges and cross-culturation with whites among whom they lived” (6). Cather includes such musical amalgamation in Sapphira when Black and white congregants and mourners experience music together at church and at Jezebel’s funeral. It also occurs in My Ántonia, most notably when Sally Harling plays on the piano “the plantation melodies that negro minstrel troupes brought to town” (153).

Scholars and collectors often classify “Weevily Wheat” as a play-party song and game closely related to a dance but without the physical contact or movements that made dancing objectionable to some. Dena Epstein confirms the entertainment’s slave origins when she defines “play party” as “a celebration for children and young adults which originated during slavery and features games, singing, and dancing” (43). “Weevily Wheat” is part of a lively account of play-party fun enjoyed by Black Americans, as told by Alice Wilkins, born a slave in 1855; her narrative was transcribed by an employee of a Work Projects Administration (WPA) effort to record the memories of former slaves:

Wen I wuz raisin’ my chilluns, dey had dey play-parties an’ some of de games dey played wuz “Weevily Wheat,” de boys stood in a line an’ de gals in ’nuther line facin’ de boys, dey sing as de boys swing dey partners an’ den dey promenade up an’ down de line an’ swing each one of de boys an’ gals, dey sing, as dey promenade an’ dance to de music of de Jews harp.

“Oh, I won’t have none of your weevily wheat, I won’t have none of your barley, It’ll take some flour an’ half an’ hour, To bake a cake for Charley.”

Wen de parties over dey com’s home a tired an’ a happy chillun’s to dey old mammy an’ pappy, an’ to dey dreams. (S. Brown)[3]

Black Americans’ fun sometimes carried serious messages as well, revealing hardship and protest to those who could see through the disguises. Music (and stories and other aspects of life) popular with children often had metaphorical meanings for adults; words and phrases expressed covert messages. Oppressed people, whose talk was often overheard and whose every circumstance could be observed by overseers and owners, spoke coded language with meanings known only among themselves—language replete with metaphor, pun, and irony. As Eileen Southern, a Black musicologist, has written, “We know, of course, from the testimony of ex-slaves that the religious songs ... often had double meanings and were used as code songs” (200). Southern extends her claim to the “satirical song,” noting that often “the slaves slipped a derisive verse or two about white listeners into songs they were improvising thus following in a hallowed African tradition for satire” (173). Zora Neale Hurston includes in Mules and Men, her treasury of Black folklore, a discussion about “by-words”; one man says, “There’s a whole heap of them kinda bywords. [...] They all got a hidden meanin’” (125). With language they created and controlled, Black Americans became artists with a subversive message.

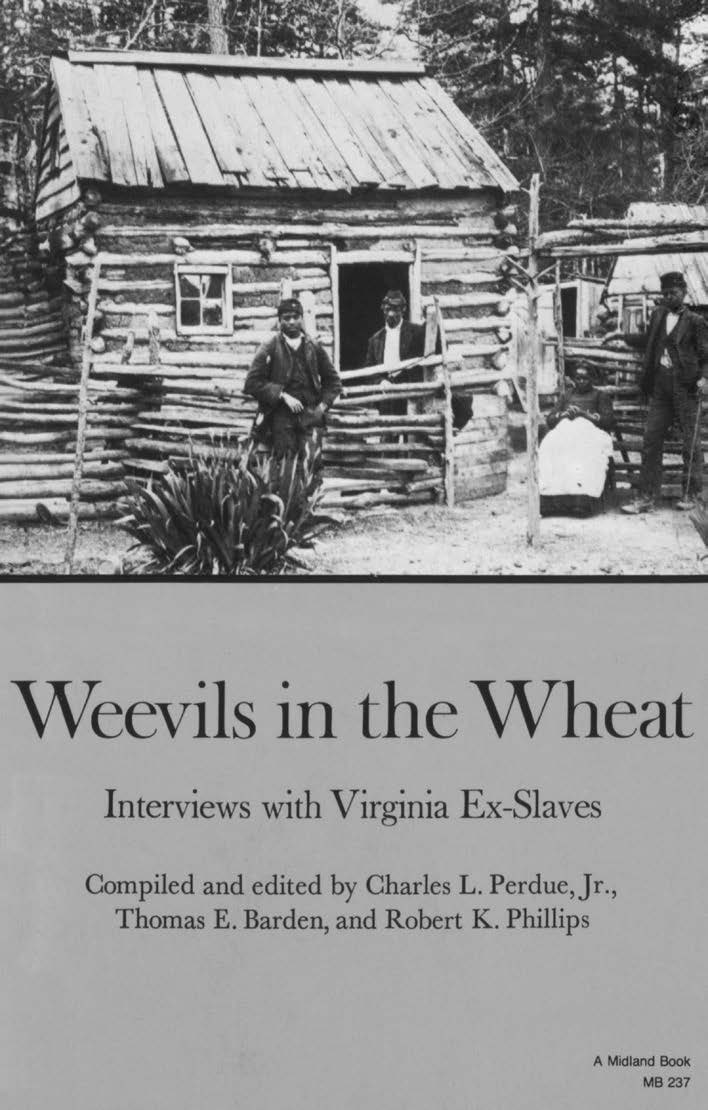

Weevil-infested wheat, the circumstance prompting the song “Weevily Wheat,” is a prominent example of coded language. In a prefatory note to Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves, the editors explain the book’s title:

Weevils in the wheat (often simply “bugs in the wheat”) was an expression used by slaves to communicate to one another that their plans for a secret meeting or dance had been discovered and that the gathering was called off. The “weevils” were either members of the patrols that were organized to discourage movement of the slaves off the plantation at night or fellow slaves who, as part of a loosely organized spy system, were willing to turn informer for small favors granted them by slave-owners. The use of such a secret code was only one of numerous adaptive strategies developed by the slaves that enabled them to lead relatively full lives—in spite of “weevils in the wheat.” (Perdue, Barden, and Phillips n.p.)

The location in Virginia of the slaves whose recollections constitute the book Weevils in the Wheat is particularly significant due to Cather’s own family heritage and her fiction set in Virginia, especially Sapphira. The phrase “weevils in the wheat” turns the tables on a common expression in white culture, “slave in the woodpile” (typically using a more racist word for “slave”), to describe people in a place where they do not belong, where they can cause trouble. Now, however, the misplaced people, the potential troublemakers, are white, and it is the Black Americans who identify them, warn others, and prevent harm. The slaves are not naïve and innocently trusting; rather, they are savvy. To sing “I won’t have none of your weevily wheat” or, as in many versions, “I don’t want none of your weevily wheat” makes a literal complaint, but it also expresses an attitude, a desire to get rid of a broad range of “bugs,” of outsiders, of troubles.

Fig. 4.1. The cover of a collection of slave narratives from Virginia. Charles

L. Perdue Jr., Thomas E. Barden, and Robert K. Phillips, editors, Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves

(Indiana UP, 1980). Reprint of 1976 edition published by the UP of

Virginia.

Fig. 4.1. The cover of a collection of slave narratives from Virginia. Charles

L. Perdue Jr., Thomas E. Barden, and Robert K. Phillips, editors, Weevils in the Wheat: Interviews with Virginia Ex-Slaves

(Indiana UP, 1980). Reprint of 1976 edition published by the UP of

Virginia.

An aspect of Black life particularly fraught with double meanings and coded language was sex. Sex was a nearly inescapable source of trauma and anxiety and a tool white people used to control and dominate Black Americans during and after slavery. Sex can also be characterized as fun; it is often a source for jokes and other comic forms. Consequently, sexual double entendres were (and remain) common. “Weevily Wheat” probably carries such language. In 1927 Guy B. Johnson wrote about “the presence of double meanings of a sex nature in the blues” and other “Negro songs” (12, 13). Johnson points out common terms for female sex organs, including “bread,” “cookie,” “cake,” and “short’nin’ bread” (14). If, as Johnson argues, “[m]y baby loves short’nin’ bread” is sexual innuendo, then “make a cake for Charley” likely had a sexual double meaning. At least one of Talley’s “Weevily Wheat” variants carries sexual overtones:

Charlie’s up an’ Charlie’s down. Charlie’s fine an’ dandy. Ev’ry time he goes to town, He gets dem gals stick candy. (84)

The potentially risqué vocabulary (up an’ down, fine an’ dandy, stick candy), the targeting of “dem gals,” and the offer of sweets for presumed favors insinuate sexual meanings, both pleasurable and threatening. Cather uses this paradoxical connotation of sweetness when she recounts the history of Old Jezebel in Sapphira. When the young Jezebel was inspected by a doctor for a prospective buyer, the doctor offered her a square of maple sugar, apparently to test her disposition. Cather writes, “She crunched it, grinned,and stuck out her tongue for more” (97). This moment captures Jezebel’s spirit but also contains sinister implications of a sexual nature.

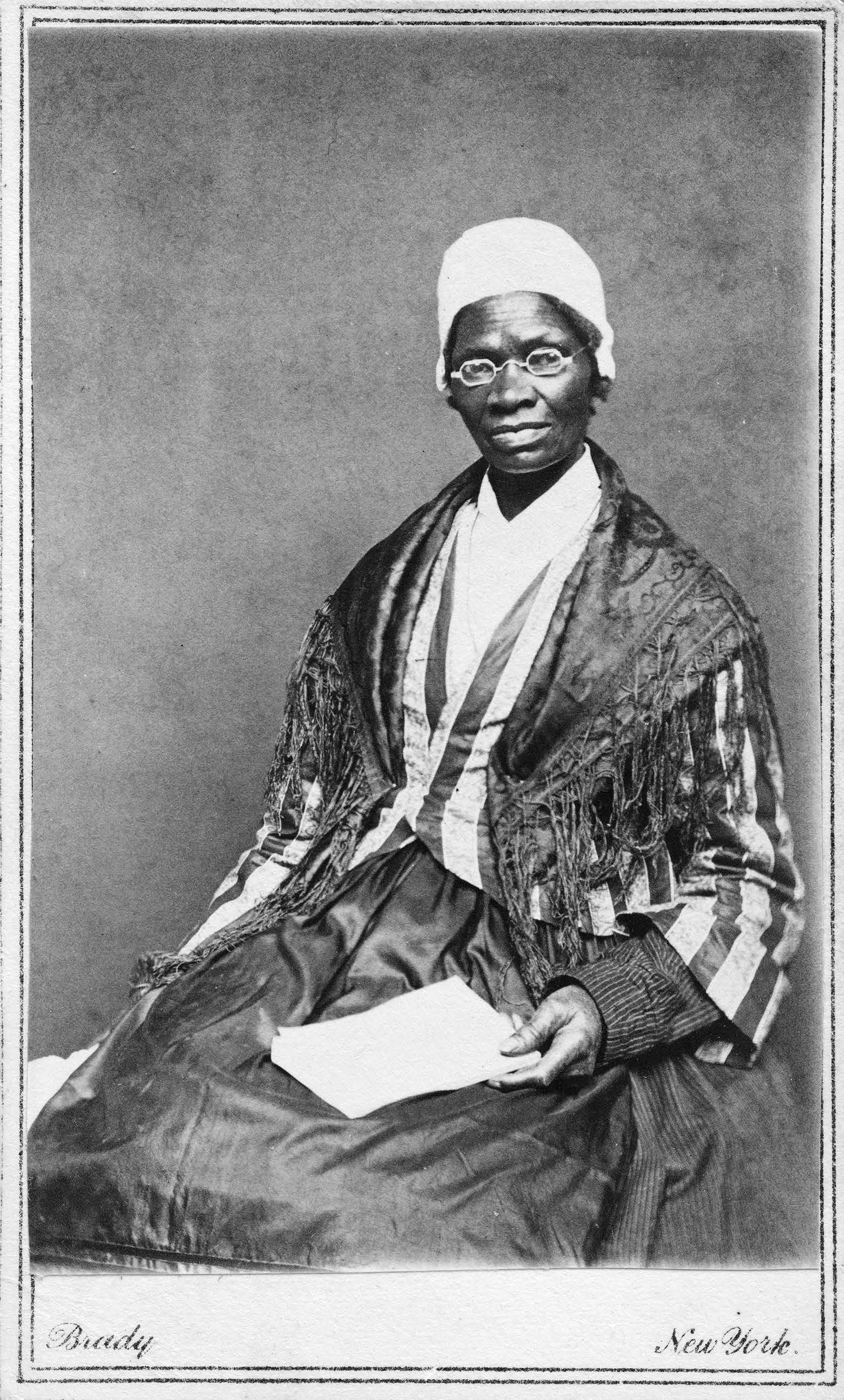

An earlier and more politically charged use of “weevily wheat” occurred when Sojourner Truth spoke the words. Margaret Washington, in her biography of Truth, provides context and an example: “Sojourner Truth ... especially loved speaking in parables, using fables, metaphors, and humorous anecdotes to unravel or reduce complexities to simple yet serious understanding. Her ‘weevil in the wheat’ was a master parable that contextualized a major issue and revealed her signifying technique” (282–83). In response to the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision that Black Americans were not protected under the Constitution, Sojourner Truth spoke a comparison to the weevil-in-the-wheat as a way to criticize the decision. Washington records the account of Truth’s Quaker friend Joseph Dugdale:

“Children, I talks to God and God talks to me,” she said. “Dis morning I was walking out, and I got over de fence. I saw de wheat a holding up its head, looking very big.” Her powerful deep voice rose as she emphasized VERY BIG, drew up to full height, and pretending to grab a stalk of wheat, she discovered “dere was no wheat dare!” She asked God, “What is de matter wid dis wheat?” And he says to me, “Sojourner, dere is a little weasel [sic] in it.” Likewise, hearing all about the Constitution and rights of man, she said, “I comes up and I takes hold of dis Constitution.” It also looks “mighty big, and I feels for my rights, but der ain’t any dare.” She again queried God, “What ails dis Constitution?” The Constitution, like the infested wheat, was rotten, and God declared, “Sojourner dere is a little weasel [sic] in it.” (283)

Sojourner Truth emphasizes the infectious, destructive nature of the weevil, and she powerfully casts her talk in religious terms with God pointing out the cause of the evil. To sing “I won’t have none of your weevily wheat” affirms the ability to perceive rottenness and the courage to reject it.

“Weevily Wheat”—in terms of song, language, ideas—was significant to Black Americans as entertainment but also as a commentary on slavery and discrimination. The words Cather includes in My Ántonia certainly make more sense coming from enslaved and mistreated people than from children. Furthermore, Cather extends the gendered nature of resistance from the household slaves of Sapphira to the “hired girls” of My Ántonia. “Resistance was woven into the fabric of slave women’s lives and identities,” argues Elizabeth Fox-Genovese while locating this resistance in daily life: “The ubiquity of their resistance ensured that its most common forms would be those that followed the patterns of everyday life” (329). When “Weevily Wheat” is removed from the dance floor and the mouths of children and examined in the context of slavery or other oppressed peoples, especially women, its participation in the language of resistance becomes apparent. The words carry a burden (making do with weevily wheat) yet speak resistance (I don’t want). Viewed in this way, the speaker or voice is transformed from a teasing child to a strong female resistor of injustice demanding something better:

I won’t have none of your weevily wheat, And I won’t have none of your barley, But I’ll take a measure of fine white flour [...]. (My Ántonia 154)

Fig. 4.2. Sojourner Truth, circa 1864. Mathew Brady Studio. National Portrait

Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Fig. 4.2. Sojourner Truth, circa 1864. Mathew Brady Studio. National Portrait

Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Here is awareness of unfair treatment of workers: the usual ration for slaves and servants was lousy wheat and rough grains. Refined flour was reserved for masters and the wealthy. Cather knew the unfairness if not the particulars, both from her knowledge of culture and literature and from observation; she had written of the harsh reality of Ántonia’s family eating frozen, rotten potatoes they got from the postmaster’s garbage (72). Among cultural figures who expressed sympathy for workers is Frederick Douglass, who recorded a widely known slave song in his autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom:

We raise de wheat, Dey gib us de corn; We bake de bread, Dey gib us de cruss; We sif de meal, Dey gib us de huss; We peel de meat, Dey gib us de skin, And dat's de way Dey takes us in. (202)

The injustice for those who did the work is obvious even though slaveholders often tried to argue that their slaves were cared for and happy. The people who planted the wheat, cultivated and harvested it, kept the flour mill going, then baked and served the bread usually received only bits and pieces of secondhand rations. And they knew it.

The preference in “Weevily Wheat” for “fine white flour” over barley and rough wheat acknowledges a historical reality. Harold McGee, in On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, points out the historic nature of negative feelings about barley: “The historian Polybius (2nd century BC) reports that reluctant soldiers were punished by confinement and barley rations, and Pliny said that ‘barley bread [. . .] has now fallen into universal disrepute.’ In the Middle Ages, and especially in northern Europe, barley and rye breads were the staple food of the peasantry, while wheat was reserved for the upper classes” (235). The desire for quality wheat is present in most versions of “Weevily Wheat,” but of the more than thirty American versions I have seen, only Cather includes the word white, a word that goes beyond description to carry racial undertones, especially in the context of Virginia rather than Nebraska. Usually the lyric reads “I want some flour and half an hour,” although Dale Cockrell, who has written about Laura Ingalls Wilder’s use of the song, once represents the line as “I’ll take the very best of wheat” (Music 48) and another time as “I want fine flour in half an hour” (Ingalls Wilder Family 17). With her choice (or memory) of “white,” Cather evokes a Black folk tradition satirizing white food. The exuberance of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “The Party,” for example, celebrates that “[w]e had wheat bread white ez cotton an’ a egg pone jes’ like gol’” (85). Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps cite tales in which food has racialized implications, including, “In a Pittsburgh hash-house one day a Negro customer said to another one at the counter, ‘here you are up North ordering white bean soup. Man, I know you are really free, now’” (503). Occurring before the Blind d’Arnault episode, the word white in “Weevily Wheat” seems to mean little in My Ántonia, probably nothing beyond description, but in racially mixed settings like Virginia it would have been a meaningful code word.

In Sapphira and the Slave Girl Cather repeatedly demonstrates her awareness of the distinction between refined wheat flour and flour made from other grains. Her precise mentions of light bread and white flour indicate Cather understood the complex economic, social, and racial meanings of such labels. The first example occurs when Sapphira gives instructions to the kitchen slave Lizzie about preparation of food for watchers during Jezebel’s wake: “Mrs. Blake will tell you how many loaves of light bread to bake” (101). Calling attention to the significance of “light bread,” Cather includes a rare footnote explaining that “‘[l]ight’ bread meant bread of wheat flour, in distinction from corn bread.” Light bread is a mark of Sapphira’s generosity and her desire that Jezebel be paid respect, but it is also a mark of Sapphira’s concern for appearances. Bread made from good wheat flour is a clear example of noblesse oblige, of Sapphira doing her perceived duty to take good care of her slaves and to sustain her reputation.

White flour is a point of pride at the Colbert mill. When Henry Colbert presents to Sampson, his head mill hand and slave, a plan for securing Sampson’s freedom and a job in Philadelphia, Sampson objects because at the Colbert mill they are able to “bolt finer white flour than you could buy in town” (111). When it comes to flour—and by code word, much more—being “fine” and “white” is a mark of achievement, at the top of a hierarchy of accomplishment. The words “finer white flour” are a near echo of the lyric Cather uses in “Weevily Wheat”—“fine white flour,” words that are not usually part of the song.

The next Sapphira occurrence of fine wheat bread comes when Rachel prepares a gift basket she will take to Mrs. Ringer, who is white, at her backcountry home: “she had also a fruit jar full of fresh-ground coffee, half a baking of sugar cakes, and a loaf of ‘light’ bread. The poor folks on the Ridge esteemed coffee and wheat bread great delicacies” (119). This passage reinforces the idea that light bread is a treat brought to people of lower socioeconomic status, both white and Black, by generous rich people.

Cather’s final mention of light bread in Sapphira comes in the novel’s closing section, after the Civil War and after the deaths of Sapphira and Henry Colbert. Till, now a servant instead of a slave, tells the story of Sampson, now a successful worker at an automated roller mill in Pennsylvania. When Sampson visits the Mill Farm, he comes to Till’s cabin “every day he was here, to eat my light bread” (282). Due to the kindness of the new miller, Till still lives in her old cabin, but now she bakes light bread for herself and her guests. Sampson says, “Just give me greens an’ a little fat pork, an’ plenty of your light bread. I ain’t had no real bread since I went away.” Circumstances are different from previous instances with light bread: no longer is white bread only bestowed on economically poor people like slaves and backcountry folks by their economic superiors. Till, who still lives in much the same economic and social circumstances as when she was a slave, now has regular access to the former delicacy. Sampson, while racially united with Till, has achieved comparative economic success in “a wonderful good place” where he has “done well.” His presumed progress, however, has occurred in a large, mechanized Philadelphia mill where the machinery “burns all the taste out-a the flour” (282). Light bread is a marker of Cather’s observation that “[t]he war had done away with many of the old distinctions” (271) even as it affirms the racial, cultural, and socioeconomic importance of refined wheat bread.

Sapphira repeatedly acknowledges the significance of white bread atop the foodstuff pecking order as it portrays destructive social injustices in Sapphira’s household. Nevertheless, the novel lacks a strong voice of resistance, especially in domestic activity. Objections to slavery are expressed privately and in broad strokes and by only a few white characters. The novel’s recognition of the sexual threats and harms that accompanied slavery is important, as is the help of a free Black minister in guiding Nancy to the Underground Railroad’s promise of safety, but acknowledgment of the social injustice of the privileged class controlling the products of the laboring class is understated. A few occasions of largesse seem to satisfy the characters. The closest example of voiced resistance comes from Old Jezebel, who replies to Sapphira’s inquiry about what she might need: “The old woman gave a sly chuckle; one paper eyelid winked, and her eyes gave out a flash of grim humour.‘No’m, I cain’t think of nothin’ I could relish, lessen maybe it was a li’l pickaninny’s hand’” (90). Even near death, Jezebel refuses to play the part of the grateful slave and declines to show proper appreciation for her mistress’s visit. Jezebel’s rejection could be cast as an echo of the verse from “Weevily Wheat”: “I won’t have none of your fake manners / I won’t have none of your food / But give me a dark baby’s hand to eat / And that’s enough for me.” Such a verse does not exist, but Jezebel’s brush-off of Sapphira’s offer captures the anger in the song’s defiant refusal of weevily wheat.

Sapphira contains only veiled suggestions of unfairness, nothing like that voiced in the protest song from Frederick Douglass’s autobiography: “We raise de wheat, / Dey gib us de corn.” This note of anger and resistance, missing in Sapphira, was, however, often present in popular Black American music. The words of “Weevily Wheat,” placed in the plantation culture of the South instead of the Harling family kitchen, suddenly resound with social protest: “I won’t have none of your weevily wheat [. . .] but give me a measure of fine white flour.” The voice is assertive, firm, demanding. Structurally and rhetorically, Cather’s verse resonates with a verse of “Mule on de Mount,” from Hurston’s Mules and Men:

I don’t want no cold corn bread and molasses, I don’t want no cold corn bread and molasses, Gimme some beans, Lawd, Lawd, gimme beans. (269)

A similar but even stronger message of resistance presents itself in the folk song commonly known as “No More Auction Block.” The subtle move from “I don’t want” to “No more” powerfully opposes economic injustice. One verse in particular speaks to agriculture:

No mo’ peck of meal for me, No mo’, no mo’, No mo’ peck of meal for me, Many thousands gone. (Work 456)

Other common verses lead with the lines “no more driver’s lash for me,” “no more pint o’ salt for me,” “no more mistress’ call for me,” “no more children stole from me,” and “no more slavery chains for me.” Cornmeal and salt were usual slave rations. Including them in a litany of complaints that includes the whip, chains, and children taken from their mothers indicates that the singers knew the full range of persecution inherent to slavery. The routine distribution of a stingy allotment of poor food was a mark of white authority and control that ultimately called for a response of “no more” and “I don’t want.” Not including overt protest in Sapphira does not mean that Cather was unaware of protest in the songs and stories of Black Americans. Her artistic purposes lay elsewhere. Just as My Ántonia contains ghosts of plantation Virginia, Sapphira contains ghosts or shadows of Black Americans’ protest and resistance.

Given the prevalence of “Weevily Wheat” in the South and its racialized, symbolic meanings, it may seem odd that Cather included it in My Ántonia rather than in Sapphira, but I believe she probably did embed an allusion to the song in Sapphira. When Martin Colbert comes upon Nancy in the cherry tree, his purposes are sexual, and he greets her with the words, “Cherries are ripe, eh? Do you know that song?” (178). The explanatory notes to the scholarly edition suggest “‘Cherries Ripe,’ an anonymous old children’s song,” and “‘There Is a Garden in Her Face,’ a song by Thomas Campion,” as possible sources (Romines 493). A more likely source for Martin’s allusion is a verse included in many versions of “Weevily Wheat.” Sandburg renders it as:

The higher up the cherry tree The riper grow the cherries; The more you hug and kiss the girls The sooner they will marry. (161)

An intriguing version rendered in Black American dialect that substitutes “Sweet-uh” for “riper” appears as part of “Squirl, He Tote a Bushy Tail” in Eight Negro Songs, collected by Francis H. Abbot (Abbot notes that he collected the songs in Bedford County, Virginia):

High-uh up de cherry tree, Sweet-uh grow de cherry, Soon-uh yuh go cote dat gal, Soon-uh she will marry. (21)

This verse from a song popular among both white and Black southerners would have been familiar to people like Martin Colbert and Nancy Till, and Cather has them say both “ripe” and “sweet” in the frightening scene (177—80). The specific detail of a cherry tree; the sexual undertones of ripe, sweet fruit, particularly cherries; and the overt mention of hugging and kissing reinforce the sinister implications of the scene in Sapphira.[4] Recognizing “Weevily Wheat” as a likely point of connection between My Ántonia and Sapphira and the Slave Girl suggests other commonalities between the two novels: both feature strong women from upper and lower socioeconomic groups, both include troubling scenes with stereotyped Black characters, and both recognize the threat of sexual assault for slave women and hired girls.

If Cather carried “Weevily Wheat” in her memory bank as she moved from Virginia to Nebraska, she enacted a migratory process common to folk music, including “Weevily Wheat.” Many scholars believe it originated among the Scots-Irish people of Britain, the region from which Cather’s ancestors emigrated. Russell Ames writes that “‘Weevily Wheat’ is ancient, derived perhaps from an old Scottish play” (69). The Nursery Rhymes of England includes a version that substitutes “nasty beef” for “weevily wheat”:

Over the water, and over the sea, And over the water to Charley. I’ll have none of your nasty beef, Nor I’ll have none of your barley; But I’ll have some of your very best flour; To make a white cake for my Charley. (Halliwell 8)

In On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs, Dorothy Scarborough establishes the racial mobility of songs like “Weevily Wheat”: “One of the most fascinating discoveries to be made in a study of southern folk-lore is that Negroes have preserved orally and for generations, independent of the whites, some of the familiar English and Scotch songs and ballads, and have their own distinct versions of them” (33).

According to most scholars, the “Charley” of “Weevily Wheat” commemorates Bonnie Prince Charlie. As early as 1904 Emma Bell Miles posited, “It is not improbable that the Charley of these songs is the Prince Charlie of Jacobite ballads, for a large proportion of the mountain people are descended from Scotch highlanders who left their homes on account of the persecutions which harassed them during Prince Charlie’s time, and began life anew in the wilderness of the Alleghenies” (121). The line “Charley over the water” also suggests this view. Cather herself reinforced a relationship between Charley Harling and Prince Charlie when she wrote, “[Ántonia] seemed to think him a sort of prince” (151).[5] Understanding the Charley of the song as Prince Charlie underscores the message of economic and social disparity and the satirical method of “Weevily Wheat”; an enslaved cook in a plantation kitchen baking a cake for a prince calls for sarcasm: “Sure, just give me some good flour and I’ll bake a cake for the prince himself.” A more culturally relevant association is possible when “Charlie” is understood as a common, usually pejorative, label often used by slaves for the master, the owner of the plantation, no matter his real name: the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang defines Charlie as “white men regarded as oppressors of blacks—used contemptuously. Also Mr. Charlie, Boss Charlie.” In each of its cultural iterations, “Weevily Wheat” communicated economic and social disparity: yeoman farmers and serfs set against Bonnie Prince Charlie, house slaves set against plantation mistresses and Boss Charlie, and immigrant hired girls set against the merchant class.

Never a uniquely Black American cultural expression, “Weevily Wheat” lost its visible ties to Black culture as it spread across the Midwest and West. This process was not unusual, especially once the forced interactions endemic to slavery were replaced with the forced segregation of Jim Crow. In addition, more Black Americans stayed in the South or migrated to cities than left for the rural Midwest, where the song remained popular. It is likely that some cultural purging also occurred, a harmful process noted by Perry A. Hall in “The Appropriation of Music and Musical Forms”: “[A]s musical forms are absorbed, they eventually become reshaped and redefined, subtly and otherwise, in ways that minimize their association with ‘Blackness’” (32).

“Weevily Wheat,” like Willa Cather, landed in Red Cloud, Nebraska. Rachel Crown documents that her mother sang a version of the song (without the adjective “white”) in Red Cloud in the 1880s (45). The song and the girl both carried complex and intertwined influences, including Black American culture. We cannot know where or when Cather became aware of “Weevily Wheat,” whether in Virginia or Nebraska, whether first from connections to Black people or from family or friends, but it seems probable that she first encountered it in Virginia, where Black life touched her childhood in significant ways. In any case, it is a rich example of the ways Cather mixed experience, memory, and her broad cultural life to create art. The song is present as a Black American cultural artifact that adds significant meaning to the novel and to the ways American culture ignores, conceals, and reveals race.

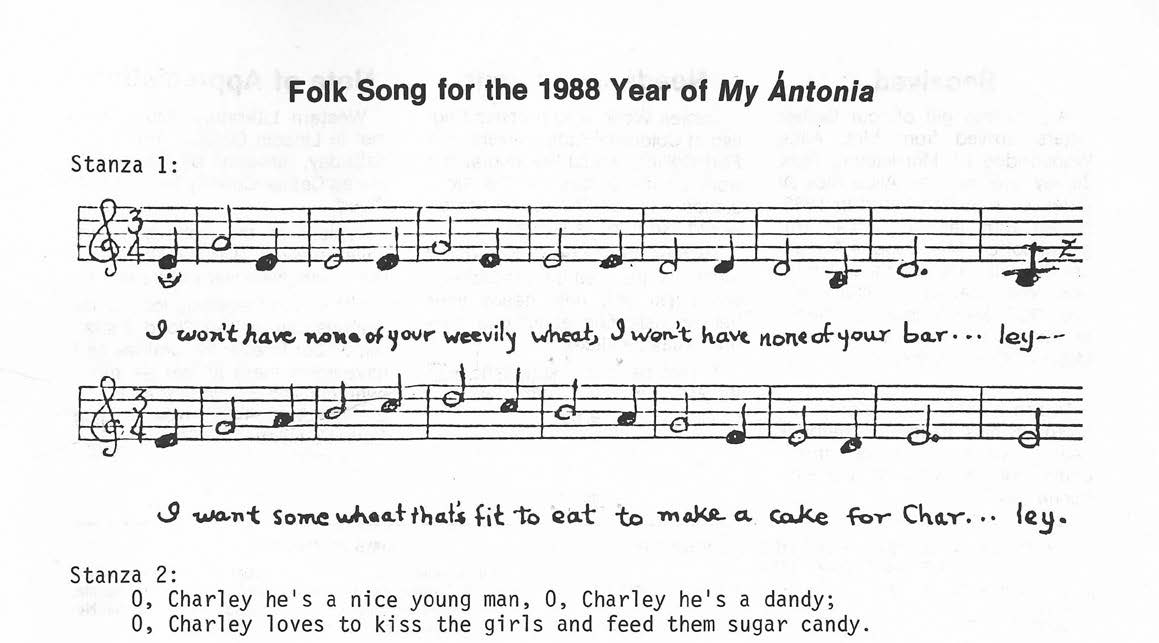

Fig. 4.3. A version of “Weevily Wheat” reported by Rachel Crown to have been

sung in Red Cloud by her mother and grandmother in the 1870s or 1880s. Willa Cather Review, vol. 31, no. 4, Fall 1987, p. 45.

Willa Cather Foundation, Red Cloud, Nebraska.

Fig. 4.3. A version of “Weevily Wheat” reported by Rachel Crown to have been

sung in Red Cloud by her mother and grandmother in the 1870s or 1880s. Willa Cather Review, vol. 31, no. 4, Fall 1987, p. 45.

Willa Cather Foundation, Red Cloud, Nebraska.

Surely Cather knew many folk songs she could have used in this moment of her novel. A study of her purposes in selecting “Weevily Wheat” is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the scene is structurally and thematically significant. It provides a transition between the harsh winter on the prairie and the increasingly troubled life of the town, and it anticipates the scene in Ántonia’s parlor near the end of the novel. The moment informs several themes: agency and voice for women who are outsiders, the importance of childhood, music and dance as counters to stifling aspects of small-town life, economic and social disparity, and more. Whether or not Cather intended a Black cultural component to this part of her novel, whether or not she knowingly or unknowingly participated in the erasure of a Black presence, the song as a cultural artifact still carries racial meanings. Cather’s lived experience of Virginia and the pieces of its culture she carried with her were diverse; they should not remain shadows or ghosts but should be examined for rich and profound meanings and for insights into Cather’s creative process.