From Cather Studies Volume 6

Wartime Fictions

Willa Cather, the Armed Services Editions, and the Unspeakable Second World War

In a 1945 article, The Saturday Evening Post reported on wartime efforts to support the troops' morale through reading. In one anecdote, a soldier, lightly wounded in the Philippines and awaiting medical rescue, reached into his knapsack and pulled out a book issued to him by the Armed Services, which he read until help arrived: "Huddled in a muddy foxhole on Leyte with a hole in his ankle, Corp. Erwin Rorick spent the hours before help came reading Willa Cather's Death Comes for the Archbishop. He had grabbed it the day before under the delusion that it was a murder mystery, but he discovered, to his amazement, that he liked it anyway" (Wittels 11). Rorick was not alone in being introduced to fiction he would not normally have read. The U.S. government had begun a massive effort to provide reading to the troops in every part of the war theater. As her part of the war effort, Cather agreed to republish some of her works in a highly unusual set of circumstances. One publication was through her old acquaintance Alexander Woollcott, and the other was through the Council on Books in Wartime.

As early as 1939, Cather had understood the gathering gloom in Europe. In The Writer and Her World, Janis P. Stout notes, "In March 1939, over a year before she completed Sapphira, she told Dorothy Canfield Fisher that having suffered the hardest year of her life, she found consolation in the one activity that could carry her through. She had abandoned the book, she said, but had taken it up again in response to the unspeakableness of another war because the routine of writing provided respite from bad news" (291). In particular, Hitler's march in Europe and France's unsuccessful efforts to resist Nazism contributed to an overwhelming sense of loss. James Woodress explains that "Cather's despair over the fall of France in June [1940] had been followed by the horrendous Battle of Britain, which began in the summer and continued while she was awaiting" the publication of Sapphira and the Slave Girl (491). However, Cather's respites were temporary, for in no way did she retreat from the world or the war. Indeed, Cather followed the war closely and in letters specifies battles and key figures. Woodress writes that "Churchill became her hero" and that she felt he was far more prescient about the threat of Hitler than the United States (491). Cather was also worried about her family members who were either fighting in the war or married to someone who was. In one letter, she sent Sigrid Undset an article about a Red Cloud pilot who shot down Japanese planes (Harbison 246).

Cather feared the worst: that civilization as she knew it would be forever changed. Edith Lewis later wrote, "Many people thought she was 'not interested' in the war; but, indeed, she felt it too much to make it the subject of casual conversation." In 1940, "when the French army surrendered, she wrote in her 'Line-a-day,' 'There seems to be no future at all for people of my generation"' (Lewis 184). Cather continued this nearly apocalyptic tone in a 1943 New Year's greeting to her friend Alexander Woollcott,[1] in which she wonders why Earth was not left as empty as the rest of the universe. Woollcott was not a particularly intimate friend, so her confidence to him seems surprising. Yet it was through this New York City acquaintance that Cather made her first contribution to the war effort.

Alexander Woollcott, member of the famed Algonquin Round Table, former drama editor of the New York Times, and columnist for the New Yorker's Shouts and Murmurs, was a powerful bon vivant in the New York theater scene. Although it is not certain how Cather and Woollcott met, they certainly attended theater and arts events during the same years. Woollcott was hard to miss in his early career as a theater critic, for he "swept" into front row seats in a black cape and cane (Kaufman and Hennessey xi). In the 1930s, he retired to Vermont, where he held sway over an estate filled with guests. Known for biting reviews, he was loved and loathed by those in the arts scene. His radio show began famously, "This is Woollcott speaking," and his tastes influenced listeners at the most powerful moment of radio, spiking sales of the authors he preferred (Kaufman and Hennessey xv).

Cather, however, was protective of her work and its publication in all forms. More than once she refused to allow him to speak of her books on his radio show, and in a letter to him she made it clear that no radio editions of her work were allowed (February 8, 1935). In 1937 she repeated her refusal to allow anyone to record her fiction to Houghton Mifflin editor Ferris Greenslet, although she later relented for editions of her work for the blind, an "exceptional permission," according to Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant (282).

Indeed, Cather was more scrupulous about her reputation in print. As former managing editor of McClure's Magazine, she knew every detail of publishing. She insisted on good typeface and decent paper, indicated by her oversight of all of her editions, from the Benda pen-and-ink drawings for My Ántonia to the Autograph series in the 1930s. In general, and perhaps on principle, Cather declined to be published in anthologies. In 1942 she at first refused editor Whit Burnett permission to publish her fiction in the collection This Is My Best, explaining that it was impossible for her to anthologize her work, even for a friend, as if it hurt her personally that her works should be in editions in which she did not have total artistic control (April 29, 1942). Burnett countered that perhaps she would allow "Two Friends" to be published, for Cather had already allowed it to be anthologized elsewhere. Eventually, Alfred Knopf himself intervened, suggesting that "Neighbor Rosicky" would be the best choice for the collection (July 18, 1942).

So it is surprising that Cather allowed Woollcott to publish her work in his anthologies, not once but twice. Wollcott's first collection, Realms of Gold, did not include any work from Cather, though it is likely that he asked her. Woollcott bravely requested "Old Mrs. Harris" for his Second Reader, but Cather flatly refused, though she nonetheless called him a good friend (July 18, 1937). Instead, she allowed "Two Friends," also from Obscure Destinies, for the anthology, perhaps because it served her purpose of reintroducing one of her favorite but lesser known stories to a new audience. She was in good company in this volume, with selections from Edith Wharton, Robert Louis Stevenson, Stephen Crane, and even Ernest Hemingway.

Woollcott's next project was more complex. As You Were: A Portable Library of American Prose and Poetry Assembled for Members of the Armed Forces and the Merchant Marine was developed as a pocket edition to cheer the troops during World War II. Woollcott had been chief war correspondent for the Stars and Stripes during World War I, along with other New Yorker luminaries such as Harold Ross, founder of the New Yorker, and Franklin Pierce Adams, all members of the Algonquin Round Table (Kaufman and Hennessey x).

As part of the war effort, there were a number of attempts to get the troops interesting reading material. One effort, sponsored by the Book of the Month Club, donated subscriptions abroad for the troops, but it was found to be impractical (Miller 2). Another attempt, the Victory Book Campaign, sent books donated by American citizens to soldiers abroad (Miller 1). Cather mentions in a letter to Mary Miner Creighton that she had sent some of her books, though she does not specify if the books were those she owned or had written (Stout, Letters 242). The problem with this program was that there were thousands of old, useless books that had to be transported to the soldiers at a time when supplies and space were short (Miller 2).

Woollcott planned a small edition, light to carry, with selections to appeal to young men. To this end, he wrote to hundreds of writers, including his friends Thornton Wilder, Mark Van Doren, and Carl Sandburg, to ask which selections to include in the anthology; "aided by his own prejudices, he would complete the job" (Hoyt 321). Cather, one of his correspondents, suggested that young men would enjoy authors who wrote about things that focused on real life rather than style and form, such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Robert Frost, and Mark Twain. This letter gives us some of Cather's now famous literary insights, including her three favorite novels (a comment she made elsewhere), The Country of the Pointed Firs, The Scarlet Letter, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. But in the same letter she explains her youthful distaste for Sarah Orne Jewett, and she proposed that young men would also not enjoy her work.

Cather seemed completely supportive of Woollcott's project, and though no direct evidence exists, she probably agreed to have her work included not because of her friendship with him but because of her sympathy for the soldiers. The edition resulted in an early collection of America's best-loved literature, a compendium of selections that largely remain famous today: Carl Sandburg's "The Grass," Walt Whitman's "I Hear America Singing," Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods," and Clement C. Moore's "A Visit from Saint Nicholas." Interestingly, for As You Were, Cather chose "Missionary Journeys," the section of Death Comes for the Archbishop where Buck Scales nearly kills Father Joseph Valliant and Father Jean Marie Latour, ending with the introduction of Kit Carson. To Cather it may have been the most adventurous part of her novel, suggesting her sensitivity to the needs of the soldiers for interesting material.

Woollcott died in 1943, the same year as the publication of As You Were, and thus he did not see the success of the collection, which went though multiple printings, with profits donated to the United Seamen's Fund. But his publisher, Viking, took note of its success, inspiring a new series named after Woollcott's title, The Portable Library (Chatterton 40). Trysh Travis explains that "Viking publicity credits Alexander Woollcott with the idea, borrowed from the British Knapsack Anthology. But another inspiration [for the Viking portable series] was probably the Council on Books in Wartime's Armed Services Editions (ASEs), cheap paperback reprints developed specifically for service personnel. Viking editor Marshall Best served as the secretary of the Council on Books in Wartime and thus was privy to the trade-wide excitement about the ASEs" (10). The Viking Portable Library, later headed by Malcolm Cowley, became an American best-selling venture. It published many now-classic American authors, but at the time of their publication in this series, they were often unpopular or out of print (Travis 11).[2]

The other inspiration for the Viking portables, the American

Armed Services editions, captured Cather's imagination as well.

These paperback books, given to the soldiers fighting abroad,

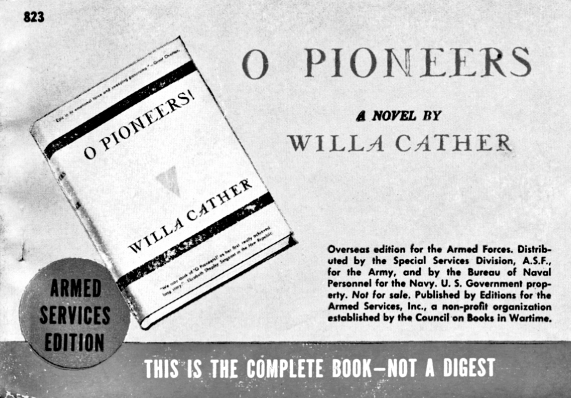

Fig. 1. The front cover of the Armed Services edition of O Pioneers! Collection of Steven Trout.

began after the war and ended in 1947. It was the answer to the previously

unsuccessful efforts to transport reading materials cheaply

and easily. This project became a massive governmental publication

venture, with 123 million copies printed of 1,322 titles (Cole 3).

Fig. 1. The front cover of the Armed Services edition of O Pioneers! Collection of Steven Trout.

began after the war and ended in 1947. It was the answer to the previously

unsuccessful efforts to transport reading materials cheaply

and easily. This project became a massive governmental publication

venture, with 123 million copies printed of 1,322 titles (Cole 3).

During the war paper was in short supply and rationed by the publishing houses. On more than one occasion Ferris Greenslet asked Cather if her work could be reprinted on a different imprint, thus saving him paper out of Houghton Mifflin's quota, but Cather nearly always refused. However, in a significant departure from some of her usual publication practices, Cather agreed to publish Armed Services editions of three of her novels: O Pioneers!, My Ántonia, and Death Comes for the Archbishop. Although Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant suggests that Cather needed "a little coaxing from her publishers" for the war editions (271), Cather must not have needed to be convinced for long, for two of her titles appear fairly early in the series, and she had allowed Heinemann, her British publisher, to reproduce a cheaper war edition of My Ántonia for the Reader's Union, a British book club (Mignon 500). Death Comes for the Archbishop was the first book published in the series. The reason for this selection is uncertain. She had published "Missionary Journeys" in Woollcott's As You Were, and perhaps publishing the rest of the novel made sense to her. But considering her comments to Woollcott about fiction she thought young men would enjoy, she may have viewed the settlement of the Southwest as adventurous.

Sponsored by the Council on Books in Wartime, the Armed Services editions were printed on pulp presses, which were less in use during the war, at a cost of five to ten cents each. The paper was light, so soldiers could easily carry the books. The books were also small, about five inches by three inches, with text in two newspaper style columns per page for easy reading. Longer books used a double imprint of the press, so they were twice the size (Cole 5). Format was set by the war board, and though Cather insisted on which edition was the textual model, she had no editorial control over these books, even though it meant that she could not, for instance, reproduce the Benda drawings for the My Ántonia Armed Services edition.

The intention of the Armed Services editions was to make available "good books, both fiction and non-fiction, for the serious reader, as well as books which the serious reader would regard as trash" (Jamieson 19). Daniel J. Miller explains that "maintaining morale among the troops became a primary objective and military officials realized that books could be instrumental in the process" (1). The first selection was a humorous collection of stories, Leo Rosten's The Education of H*Y*M*E*N* K*A*P*L*A*N, published in September 1943 (Miller 15). Most genres were represented in the series, including science fiction, westerns, sea stories, popular contemporary fiction, and cartoons for those soldiers for whom reading was difficult (Miller 17). The selection committee "consciously strove to select titles that would appeal to a general audience, [and] the wide breadth of genres encompassed is a remarkable one. Titles range from Faulkner to Margaret Mead to the latest in science fiction and murder mystery" (Miller 12; Wittels 91). Thus, a soldier could both read for entertainment and education. Not surprisingly, racy titles were popular even though they proved not racy at all, such as Is Sex Necessary?, by James Thurber and E. B. White, or Star Spangled Virgin, by DuBose Heyward (Miller 28-29). More challenging titles included The Republic of Plato and Virginia Woolf's The Years. Very few books were banned, but E. B. White was thrilled when his Armed Services edition of One Man's Meat was thought controversial and temporarily halted from distribution (Miller 32). Ironically, The Letters of Alexander Woollcott was rejected; the artistic bon vivant who inspired the series was thought "too coy for masculine appeal" (Wittels 92). Cather took no part in the selections, but the series included a number of her favorite authors in the 1,322 titles, such as A. E. Housman, Mark Twain, and Katherine Anne Porter. Cather's dear friend during the war years, Sigrid Undset, agreed to publish The Bridal Wreath, the first volume of the Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy that brought her the Nobel Prize in literature in 1928. Ninety-nine Armed Services editions were so popular that they were reprinted more than once, such as A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, by Betty Smith, The Robe, by Lloyd C. Douglas, White Fang, by Jack London, The Yearling, by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Klondike Mike, by Merrill Dennison. Although these books later became collectors' items, some of them are impossible to find because they were "read to tatters" (Wittel 11). The last edition in the series was Ernie Pyle's Home Country, published in 1947.

The popularity of these books has been well documented. David G. Wittels writes that soldiers anxiously awaited their delivery and even split them in half so more than one person could read them, even though it meant that someone began the story in the middle (92). John Cole notes that "One copy of an Armed Services Edition was issued to each soldier as he boarded the invasion barge" before Normandy (9). The C and D series were specifically reserved for the Invasion of Normandy (Hackenberg 18), and Cather's Death Comes for the Archbishop was in that series. Letters do not indicate if she knew that fact. Although soldiers were generally instructed to forgo unnecessary items, "the men abandoned souvenirs, spare shoes and blankets, but not a single one of these books was left behind" (Wittels 92). One soldier, Capt. J. H. Magruder, wrote to the Saturday Evening Post about the scene of dead men after a battle in the South Pacific. The sad irony of one soldier struck him in particular: "As I looked down at him, I saw something which I don't think I shall ever forget. Sticking from his black trouser pocket was a yellow pocket edition of a book he had evidently been reading in his spare moments. Only the title was visible—Our Hearts were Young and Gay" (62).

Of the three Cather books published in the series there are sales records only for My Ántonia. In March 1944, "Cather's first royalty check was for 803.38, which meant that 80,338 copies of Ántonia had been sold" in a relatively short time (Crane 74). Cather split the check evenly with Houghton Mifflin (October 13, 1944), as the governmental contract stipulated. The penny royalty was from the government; soldiers did not pay for the books, and they were not available to civilians. Nonetheless, it shows Cather's popularity among the soldiers and the development of a new fan base. One of the drawbacks to this popularity was that soldiers wrote to her. James Woodress explains that "the only contribution [Cather] could make to the war effort, it seemed, was to respond to her fan mail from the far-flung battlefields" (500). But she also "admitted that her awareness of homesick soldiers in foxholes had become a nervous strain" (Stout 304-05).

Cather does not specify the number of letters she received, but her correspondence could have been considerable, and she took it very seriously. Living authors of books published in the Armed Services editions got anywhere from hundreds to thousands of letters. James Thurber remembers two hundred replies to his six titles in the series, but H. Allen Smith received five to ten thousand responses from soldiers. Betty Smith, author of the best-selling A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, "received ten times more service mail than letters from civilians reacting to her novel" (Hackenberg 19).

Cather's preference against being anthologized continued after this project. Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant bravely volunteered to edit a Viking Portable edition for Cather, for the new series was renewing the literary reputation of authors who were out of print or out of fashion. Instead, Cather seemed furious with her old friend for even considering it. Stout writes that Cather was "amazed that any self-respecting writer would agree to such a thing" (Writer 306). Sergeant explains that Cather "thundered against the trend to anthologize, to cut books to small pattern for magazines, to reproduce fragments in 'portables.' It's a sorry comment on our times, she would say, sarcastically—why waste energy wading through a long novel if you can know the author from a single excerpt?" (282). To Cather, reading itself was a sacred experience. Carefully constructed books and artful fonts preserved the grace and beauty of the relationship between book and reader. Only exceptional circumstances, and the Second World War was one of them, could be worth compromising those values.

In spite of her old-fashioned publishing ideals, Cather nonetheless remained popular after her death in 1947 and long after the war years. The Armed Services editions were arguably a part of that success. By 1948 there were seven million former GIs enrolled in American colleges and universities (Travis 17). These veterans changed the landscape of American education. Miller concludes that the Armed Services editions helped "cement" the post-World War II paperback market (36). Sales of smaller editions skyrocketed and also became part of the textbook industry. The authors who were published in the Viking Portable series and the Armed Services editions were among the better-known authors of the era. Through her heartfelt war effort, Cather became a part of this populist movement.