From Cather Studies Volume 6

The "Enid Problem"

Dangerous Modernity in One of Ours

Woman, German woman or American woman, or every other sort of woman, in the last war, was something frightening.

The very women who are most busy saving the bodies of men: . . . these women-doctors, these nurses, these educationalists, these public-spirited women, these female saviours: they are all, from the inside, sending out waves of destructive malevolence which eat out the inner life of a man, like a cancer.

—D.H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American LiteratureIn the epigraph, D. H. Lawrence redraws the battle lines of World War I as a war between the sexes rather than a war between nations. He describes the war as an occasion upon which women exerted a "destructive malevolence" toward men, rather than as a conflict during which armies of men wounded and killed each other. In his account, the war's most damaging wounds were (and still "are") inflicted by a monstrous New Woman.[1]

Lawrence's misogyny comes as no surprise. But it is surprising that a similar misogyny also structures postwar writing produced by women writers such as Willa Cather. Cather herself was something of a New Woman, who had challenged professional and literary notions of women's proper sphere. She had herself been an "educationalist," had once had ambition of becoming a "woman-doctor," and had, in print, advocated nursing as a profession for women ("Nursing" 319-23). Her status as an independent and professional woman, famously discontented with traditional gender roles, makes her recourse to the same vituperative antifeminist logic that we hear from Lawrence curious.[2] Yet, her war novel, One of Ours (1922), traces the damage suffered by its male protagonist to female monstrosity—a monstrosity symbolized, by Cather as by Lawrence, by female action and independence called up by the war effort.

One of Ours narrates the experience of its protagonist, Claude Wheeler, who experiences a masculine crisis. Claude's crisis is both vague and overdetermined, and it provides the precondition for a war experience that enables him to come into his own as a man. Rather than depicting the war as traumatic for men, Cather traces its modern wounds to women—particularly to Claude's wife, Enid—and then jettisons them from the novel. Marilee Lindemann notes that both war and misogyny play a role in the recuperation of Claude's masculinity (74). What has not been appreciated, though, is the relationship between the war, particularly its modernity, and Enid's unnatural femininity. Cather characterizes Enid through a series of tropes that pervaded representations of women's roles in the war: practicing home economy, nursing, and driving. Through these tropes, Enid comes to stand for a paradigmatic New Woman, whose bids for independence threaten men. Why do both Cather's and Lawrence's postwar writings express dismay, not at the violence done by men nor at women who stayed at home as if content to let men suffer but by "nurses," "doctors," "educationalists"—women "saviours"?

One of Ours has invited perpetual controversy for its depiction of World War I. It won a Pulitzer Prize and was a commercial success, but its critical reception records the mixed feelings that the war inspired in Americans in 1922. The novel provided an occasion for a debate about the war, its representation, and its place in recent memory.[3] Scholars have continued to disagree about the novel's attitude toward the war.[4] For many readers, then and now, Cather's depiction of the war seems too romantic because it provides an opportunity for traditional and heroic masculine achievement. Before the war, Claude Wheeler is tormented by vague desires: he wants a more "splendid" life (52). The war fulfills this desire by giving him a chance to act heroically. To many, Cather's depiction of Claude's "clean" wounds and glorious battlefield death sanitizes the horror of trench warfare (453). Yet, other critics note the ironic tone at the novel's conclusion, in which Claude's mother reflects on her son's naïve illusions.

I would argue that Cather's direct representation of the war is actually rather well balanced. She incorporates evidence of the war's destruction as well as its excitement. Claude loves being a soldier. Cather describes the strange—even repulsive—elation that the death of others inspires in him. As letters, diaries, and other records of combatant testimony—including those from her cousin G.P. Cather, on whom Claude is based—attest, this perspective is not universal, but it is authentic.[5] Claude's heroic notions (shared by some actual soldiers) were authorized and invited by propaganda that pictured Pershing's American Expeditionary Forces as heroes. Cather remains faithful to the perspective through which her protagonist viewed the war, but she also frames it as such.

I would like to shift the debate over the novel's depiction of the war back to the Nebraska section of the novel and to what Sinclair Lewis dubbed the "Enid problem." The novel's real interest, Lewis argued in his review, was the problem posed by Claude's wife, who refuses to consummate their marriage: "Here is young Claude Wheeler, for all his indecisiveness a person of fine perceptions, valiant desires, and a thoroughly normal body, married to an evangelical prig who very much knows what she doesn't want" (O'Connor 128). Having created this interesting conflict, Lewis argues, Cather didn't know how to finish her story. She "throws it away," he says, by arbitrarily sending Claude off to war: "She might as well have pushed him down a well" (O'Connor 129). In lamenting the novel's turn to the war, Lewis underestimates the pathos that it was still capable of evoking in many readers (as many reviews attest). He also oversimplifies the novel's central problem, which centers not just in Enid but in Claude. In pronouncing that Claude has a "thoroughly normal body," Lewis ignores his dread of sexual encounters with women and his "sharp disgust for sensuality" (56). The "Enid problem" makes this easy for Lewis—and many readers—to forget. Enid's refusal to consummate their marriage takes the focus away from Claude's ambivalent sexuality and leaves the reader to assume, as Lewis does, that Claude has a "normal" body, with normative desires. But before Enid refuses him, Claude seems less normal, even "queer," as his friend Ernest puts it (138). In his reading of the novel, Lewis accepts and reiterates its scapegoat structure, remaining blind to the ideological work done by Cather's pejorative picture of the New Woman.

Cather invites Lewis's reading by making Enid extremely unsympathetic. She portrays Enid's refusal of Claude on their wedding night in a way that forbids sympathy: Enid locks him out of their stateroom on the train with a complaint so trivial it cuts ("Claude, would you mind getting a berth somewhere out in the car tonight? . . . I think the dressing on the chicken salad must have been too rich" [195]). The next morning, after Claude's humiliation has been compounded by a "long, dirty, uncomfortable ride," Enid greets him with a "fresh smiling face" and the (cruelly?) ironic observation that "[she] never lose[s] things on the train" (198)—including her virginity. Enid's portrayal plays a crucial role in the novel's economy of sympathy. As if in accord with a law of constants that governs the distribution of the reader's finite amount of sympathy, Cather demonizes Enid so that the reader will begin to favor Claude. The explicitness of the "Enid problem" compensates for and adumbrates the "thing not named" in One of Ours: Claude's "problem" (Cather, "The Novel Démeublé" 41).

This more latent conflict remains cloaked in obscurity. Claude is simply, as his mother describes it, "on the wrong side" of his differences with and from the men around him (53). The vagueness of this phrase reflects not only a mother's desire to shield a beloved son but the imprecision that characterizes this conflict within the text at large. Cather equivocates about whether Claude's differences reflect his own inadequacies or those of his society. Vague descriptions of Claude's "problem" pervade the first section of the novel: he harbors unreasonable fears; his attempts to be valiant fail; he is easy to manipulate; and he pleases himself best by "impos[ing] physical tests and penances upon himself" (29). Cather's portrait emerges: weak, at the mercy of his emotions, and vulnerable to others' manipulations, Claude develops masochistic tendencies. Claude's masochism shapes the reader's response; his impatience with himself exhausts our patience in turn, which is worn thin by the repetitious, and repetitiously superficial, accounts of what's "wrong" with him (53).

Claude's problem provokes continual speculation: Claude knew, and everybody else knew, seemingly, that there was something wrong with him. . . . Mr. Wheeler was afraid he was one of those visionary fellows who make unnecessary difficulties for themselves and other people. Mrs. Wheeler thought the trouble with her son was that he had not yet found his Saviour. Bayliss was convinced that his brother was a moral rebel, that behind his reticence and his guarded manner he concealed the most dangerous opinions. . . . Claude was aware that his energy, instead of accomplishing something, was spent in resisting unalterable conditions, and in unavailing efforts to subdue his own nature. When he thought he had at last got himself in hand, a moment would undo the work of days; in a flash he would be transformed from a wooden post into a living boy. He would spring to his feet . . . because the old belief flashed up in him with an intense kind of hope, an intense kind of pain,—the conviction that there was something splendid about life, if he could but find it! (103)

Cather introduces a series of codes to describe what's "queer about that boy," each inflected by a different ideological perspective and anxiety: his father fears he's a "visionary fellow" (a Greenwich Village "artistic" type); his mother fears he's a sinner; his brother fears he's a secretive radical. The characters who attempt to name what is "wrong" with Claude fall short—a warning for later generations of readers and critics. For although Cather's lack of specificity invites interpretation, it also defies it.[6] That said, a certain gender trouble seems undeniable: Claude fails to express a maleness that is often assumed to be natural and struggles with "his own nature." Not surprisingly, recent critics have read Claude's problem as that other unnamable, the love that dare not speak its name. Echoing Cather's own account of her aesthetic practice of withholding information in "The Novel Démeublé," Timothy Cramer glosses Claude's mysterious problem as a counterpart of her lesbianism: "The thing not named in Cather's life, of course, is her homosexuality, and its presence is divined throughout much of her work" (151).[7] According to this line of thinking, the war provides a solution to Claude's crisis by giving him a chance to work and live not just in a homosocial relationship to other men but in an explicitly homosexual one.[8] Once in France, Claude meets David Gerhardt, and their relationship eventually inspires confidence in Claude. But reading their relationship as "openly gay," as Cramer does, overstates matters. Army life does consolidate Claude's masculinity, but we need to think more broadly about the malaise it cures.

Claude's problem resembles a condition identified in 1919 as "American Nervousness," an ephemeral neurosis blamed for sapping American manhood. "Our whole continent has been growing nervous. Everywhere we have had a steady increase in all forces making for neuroticism," Frederick E. Pierce worried in the North American Review (81). Modern life was corroding the virile traditions of American life. Claude echoes this diagnosis when he later refers to his "enervated" boyhood (419). Cather's diction and imagery suggest that Claude's problem is his lack of masculinity— the fact that he is a "sissie," as Claude thinks his name sounds. As Susan J. Rosowski argues, "[Claude's] best moments are those in which he assumes conventionally female roles. . . . Conversely, he is most miserable—and violent—when doing what is expected of him as a man" (111). Cather figures what's "wrong" with Claude through a series of sexually and gender-coded keywords, including "nervous" and "queer," that, as Lindemann puts it, "snap crackle and pop" with the tensions of "acute anxiety and ideological work" (12). It is tempting, but too simple, to read such terms as referring only to Claude's sexual orientation. The regime of normative masculinity requires more than heterosexuality. Claude's gender trouble signifies his resistance to, or failure to meet, multiple social expectations.

In some moments, for instance, Claude's inadequacy surfaces as a lack of vocation. He chafes at the question of money and profession: "I don't believe I can ever settle down to anything," he tells a friend (52); he feels "a childish contempt for money-values," a phrase that traces his failure to come of age to his attitudes towards modern, consumer society (101). This failure to fit in to existing economic structures seems odd in a novel about a western farmer. Claude's economic and social standing locate him within a producer class of yeoman farmers rarely associated with effeminacy or "nervousness." Claude will inherit a farm; he is neither at leisure nor alienated from his labor (as are his father's hired men). Instead, the strength he exerts with his male body on what will be his own land would seem to offer a solid material basis on which to build a coherent identity. But it doesn't because, in Cather's novel, the West—so long imagined as an escape from the degenerate, modern world—has been infiltrated by machines and what Anthony Giddens describes as "disembedding mechanisms," or new technologies that reorganize space and time and uproot individuals from their cultural and vocational traditions (10-34). Unlike most of his community, Claude responds to these changes with hostility. "With prosperity came a kind of callousness," he muses (101); "the people themselves had changed" (102). Cather figures this callousness as a new relationship to modern machinery, particularly the automobile: "The orchards . . . were now left to die out of neglect. It was less trouble to run into town in an automobile and buy fruit than it was to raise it" (102).

These reflections of Claude's resonate with more narrative authority and eloquence than is usual. His thoughts in this passage might easily have been lifted from one of Cather's other novels or essays.[9] Visions of the lost Eden of a fruit orchard appear throughout her fiction; she repeatedly figures encroaching modernity as an assault on such a pastoral setting. This signature topos appears most memorably in O Pioneers! (1913), where an orchard provides the setting for the novel's climactic murder scene. In One of Ours, it is embedded in a lost past, when Claude recalls his father's murder of a cherry tree: "The beautiful, round-topped cherry tree, full of green leaves and red fruit,—his father had sawed it through! It lay on the ground beside its bleeding stump" (27). Claude identifies the "bleeding stump" of the cherry tree with himself and his future. The scene and its memory leave Claude feeling angry and paralyzed; his father's power to cut down the fruitful tree turns the pastoral landscape of childhood into a site of castration. This episode constitutes the novel's primal scene—the original, mythic conflict that structures Claude's problem and its narration in the novel. The whole novel seems to be an attempt to reverse this action.

With the vision of the murdered cherry tree, Cather suggests a cultural loss of innocence and a fall into modernity that have particularly difficult consequences for men. The details of Claude's castration anxiety seem inspired less by Freud than by American myth, in which cherry trees have an archetypal significance in the relationship between fathers and sons. In the tale of George Washington and his father's cherry tree, the father's law stands for right, honesty, and forbearance. Young George breaks that law by cutting the tree down. But when questioned, he finds that he "cannot tell a lie." Thus in breaking the father's law, he learns to respect and abide by it. Once chastened, Washington grows to embody and enforce the law himself, taking his place in a patriarchal line and ultimately becoming the "father" of the nation. Cather evokes this myth so as to show its degeneration. In the Wheeler family, Mr. Wheeler does not teach Claude respect for the past, since he chops down the tree he himself had cultivated for years; nor does he teach Claude to respect the future, since the tree will never bear fruit again. Mr. Wheeler commits an act of violence that destroys, rather than enforces, the law of rightful rule as it is passed from one generation of American men to the next. In Claude's fall from innocence, the father's will seems capricious, unpredictable, impossible to learn and despicable to imitate, leaving the son ambivalent about becoming a man in his own right. Not wanting to be like his father, Claude is bereft of male models to emulate.

This primal scene deidealizes the West as a masculine space free both of women and domestic entanglement. The Wheeler farm is no longer virgin land; it has been claimed and violated in a scene of implicitly sexual violence. The adventure of settlement over, the only masculine way to engage in the frontier is to fight to preserve it—to fight a battle that has been, always-already, lost.

Claude's nostalgia for the past and rejection of modernity isolates him from other men: Mr. Wheeler speculates in land and chops down the tree; Bayliss wants to tear down the oldest home in town, built (complete with the traditionally masculine retreat, the billiard room) by two "carousing" "boys" back when the town was "still a tough little frontier settlement" (109); and Ralph buys an endless series of modern "labour-saving devices" that are too difficult to use (19). In contrast, Claude shares his mother's respect for the past. When their neighbor, Mr. Royce, converts his mill to electric power, he thinks, "There's just one fellow in the county will be sorry to see the old wheel go, and that's Claude Wheeler" (148). Seen from this perspective, Claude's "problem" stems from his location in time. The frontier used to be a space where carousing boys could be men. It was a site of adventure, beauty, and drama: rugged Nature made men. All that has passed Claude by. Machines and the matrix of consumer culture that accompany them have made western life too easy, too mundane, not "splendid." His quest in "a modern wasteland" against "the foes of materialism" (though difficult, as Rosowski notes) does not seem to be enough to bring Claude's masculinity into being (Rosowski 97). Paradoxically, Claude's respect for the past does not assure his masculinity, despite its resonance with Theodore Roosevelt's call to "strenuous life" and the masculinity of an earlier generation of "tough" settlers. Encroaching modernity makes Claude's masculinity seem vulnerable, anachronistic, and effeminate.

Cather crystallizes the threat modernity poses to Claude's masculinity in the scene of an accident, which connects mechanical violence to the male body with a debilitating dependence on women. This scene acts as a lynchpin for the novel's ideological conflicts: Have you heard Claude Wheeler got hurt yesterday? . . . It was the queerest thing I ever saw. He was out with the team of mules and a heavy plough, working the road in that deep cut between their place and mine. The gasoline motor-truck came along, making more noise than usual, maybe. But those mules know a motor truck, and what they did was pure cussedness. They begun to rear and plunge in that deep cut. I was working my corn over in the field and shouted to the gasoline man to stop, but he didn't hear me. Claude jumped for the critters' heads and got 'em by the bits, but by that time he was all tangled up in the lines. . . . They carried him right along, swinging in the air, and finally ran him into the barb-wire fence and cut his face and neck up. (137-38) Modernity has already marked the family farm: Claude works in a "deep cut" that evokes both a primordial wound and the land's division into pieces of private property. This "cut" evokes the wound of birth that will be repeated in death. Claude is dragged from the cleft in the earth, as he is into life, to struggle amidst the entangling (umbilical-like) reigns and barbed wires that tie him to others and to their doom. The mutual labor of man and beast has been interrupted by machines—a motor-truck— with terrible consequences. Man's curse—labor—has been perverted and made more difficult by the conditions of modernity, despite the fact that machines supposedly save labor. Cather's "picture making" of Claude's accident evokes archetypal expressions of masculine anxiety about dependence, lack of agency, and the entanglements of fate that seem to deprive men of their power and autonomy.[10] "It was the queerest thing I ever saw": it resembles a fantasy in which all men's traditional subjects rise up against Claude—the machine, the earth, the beasts of burden, and even inanimate tools (plough and wire) conspire against their master and inventor. Yet this scene pictures modernity's wound in terms that are both primordial and historically particular: the image of a man tangled in barbed wire alludes to the closing and domestication of the American frontier and to the apocalyptic landscape of No Man's Land on the Western Front.

Having emphasized the fragility of male bodies in an industrialized world, Cather goes on to suggest that the traditional masculine response—stoicism—further endangers them. Claude attempts to deny his wound, resuming his work the day after his accident and so becoming seriously ill. There is no particular glory to be gained by working in the hot sun the day after his accident, but Claude does it anyway, acting out a masochistic martyr fantasy and displaying his ability to endure physical trials. Cather suggests that, in the absence of meaningful opportunities to demonstrate heroism, the performance of masculinity has degenerated into a series of futile and self-destructive gestures.

In the scene of Claude's accident and the plot developments that lead from it, Cather begins to change keys. The paired themes of castrating modernity and Claude's "queer" inner conflict mingle with and give way to a leitmotif that announces the New Woman. At the level of plot what happens is simple: Claude is nursed by Enid, and he falls in love with her. He imagines that marrying her will solve his "problem," as if playing opposite a woman in a marriage plot will bring his manhood to the fore. In the most literal sense, Claude is disappointed in this hope. Enid refuses to play the feminine role that he casts her in. But at another level, marrying Enid does have the effect Claude wants: she does make him seem "thoroughly normal," as Lewis puts it, both to characters within the novel and to readers. Suddenly, Claude's struggle deserves sympathy; rather than a fool, a misfit, or "queer," he seems more like a tragic hero. After this point in the narrative, Claude's crisis becomes the "Enid problem"—the problem of her rejection of traditional femininity. Enid's lack of femininity acts as a magnet, binding Claude's inadequacies to it and liberating him from their taint.

At this point the novel turns toward resolution by demonizing Enid on the one hand and celebrating Claude's experience of fighting in World War I on the other. Cather's novel wishfully splits Claude's problem—modernity, his place in history—in two. Enid comes to embody the threatening aspects of modernity and machine culture, while the war comes to stand for an ironically antiquated, antimodern crusade carried out in the name of "history." The drive for narrative resolution outweighs the imperatives of realism (and, we might add, feminism).

Claude imagines himself fighting not just the Germans but an attitude toward modernity that exists in the United States as well: "No battlefield or shattered country he had seen was as ugly as this world would be if men like his brother Bayliss controlled it altogether. Until the war broke out, he had supposed that they did control it; his boyhood had been clouded and enervated by that belief. The Prussians had believed that too, apparently. But the event had shown that there were a great many people left who cared about something else" (419). Claude's anachronistic fantasy enables him to filter out awareness not just of the war's ugliness but of its modernity: "The intervals of the distant artillery fire grew shorter, as if the big guns were tuning up, choking to get something out. . . . The sound of the guns had from the first been pleasant to him, had given him a feeling of confidence and safety; tonight he knew why. What they said was, that men could still die for an idea; and would burn all they had made to keep their dreams. He knew the future of the world was safe" (419). "Safe," the phrase goes, "for democracy." In the way it echoes Wilson's famous declaration, Cather's text registers ideology's power to shape point of view and experience far beyond the limits one might imagine. To most who heard them, the sounds of the "big guns" meant something else altogether: not that the "world was safe" but that machines had facilitated a new level of danger. In 1918 (when this scene is set), the German army was using the biggest guns yet manufactured to send an altogether different message to the civilians of Paris: that nothing was "safe"; that the front lines of the battle extended to what seemed like almost infinite distances. The "big guns" metonymically evoke the range of innovative technologies used in World War I—including not just artillery but also submarines, airplanes, chemical weapons, and so on— and so mark the modernization and mechanization of war, the very thing against which Claude imagines he's fighting. Yet ironically, Claude hears the sounds of bombardment—the voice of mechanized war, pure and untranslated—as evidence that he's winning a war against modernity. In moments such as these, Cather's novel strains against a difficult contradiction.

The war's destructive violence does find its way into the novel —but not where it is most often sought, in the final third set in France. Instead, the most dystopic elements of the war and its modernity surface and disappear in the Nebraska part of the novel. Enid embodies what is to Claude—and to Cather, I think— the most frightening aspect of the war: its modernity. And here, Cather's narrative does harbor and structure romantic sentiments; Cather too is fighting Claude's fight.What is most curious, though, is that her narrative frames the fight againstmodernity as a war between the sexes, as a fight for sympathy between Claude and the New Woman. One of Ours conflates a nostalgia for "natural" preindustrial frontier life with a nostalgia for traditional femininity and a traditionally heterosexual union and division of labor.

THE "ENID PROBLEM" REVISITED

In Book II ("Enid"), Cather's novel turns away from what's "wrong" with Claude to what's "not natura[l]" (131) about Enid's femininity. Enid comes to stand for the war's dystopic aspects through her association with a series of visual and verbal tropes that present women in relation to the war effort. Cather specifically refers to popular media and the powerful ways gender had been displayed in images designed to generate consent for the war. Perhaps because of the United States' relative distance from the theater of war, its shorter period of official engagement, and its comparatively few—though still substantial (over fifty thousand combat mortalities)—casualties, the cultural impact of the war has been under-appreciated. Reading Cather's novel requires a deeper understanding of how close the war seemed to Americans. Cather refers specifically to a range of visual references, particularly recruiting posters, which brought the war home to Americans.[11] Walter Rawls reports that "America printed more than twenty million copies of perhaps twenty five hundred posters, more posters than all the other belligerents combined" (12). Cather's novel corroborates his claim that "it was on the main streets of Home Front America that these posters did their job so effectively" (12).

In One of Ours, Cather alludes to recruiting images in a variety of ways. Claude's fight against modernity echoes pictures of the American forces as "Pershing's Crusaders," a band of chivalric knights. Before that, when Claude tells his neighbor, Leonard, that he plans to enlist, Leonard responds, "Better wait a few weeks and I'll go with you. I'm going to try for the Marines. They take my eye." Claude, standing at the edge of the tank, almost fell backward. "Why, what—what for?" Leonard looked him over. "Good Lord, Claude, you ain't the only fellow around here that wears pants! What for? Well, I'll tell you what for," he held up three red fingers threateningly, "Belgium, the Lusitania, Edith Cavell. That dirt's got under my skin. I'll get my corn planted, and then Father'll look after Susie till I come back." (236) Leonard lists the highlights of the Allied propaganda war: "Belgium, the Lusitania, Edith Cavell." All three were pictured in propaganda posters that appealed particularly to men by presenting the war as assaults on vulnerable women. Cather draws our attention to visual mediation: the Marines "take [Leonard's] eye"; "he looked Claude over" before suggesting they both "[wear] pants" (a visual trope for manhood); his words are accompanied by a striking physical pose ("he held up three red fingers threateningly"). Visual tropes of female vulnerability in need of male defense have reinforced Leonard's sense of his role as a man in the family (he "wears pants") and of his wife's vulnerability ("Father'll look after Susie").

Cather alludes to the impact of visual propaganda evenmore explicitly in her depiction of Mahailey, a character who takes graphic representations of the war as pictures of reality. Mahailey feels as if she has direct access to the war through these images. Her distance from the war is overcome by the immediacy of the graphic images, and she feels herself to be at war. Though Mahailey is simpleminded, her response to propaganda alerts the reader to the reach of visual propaganda. Historians describe World War I as the first "total war," and a primary aspect of its totalization is the militarization and mobilization of civilian life. Even by staying at home and within a traditionally feminine domestic sphere, women such as Mahailey were invited to think of themselves as combatants on the "home front." "Total war" was a byproduct not only of an industrialized economy but also of new modes of mass communication, including newspapers, film, and war posters.

Alerted by Cather to the effectiveness of visual propaganda and the extent to which it reached Americans even in rural areas, I suggest that we attend to the ways in which Enid reflects and condenses images of a certain kind of active and modern femininity that appeared in war posters. Unlike the images of women in need of male defense that seem to motivate Leonard, many posters figured women as contributing to the war effort in a variety of ways: by doing either "women's work" or more masculine kinds of labor on the home front and by working abroad near the front.[12] On the face of things, these representations seem to advance feminist ideals. They suggest the war sparked a reevaluation of the notion of female passivity and fragility and offered a new range of actions to women.

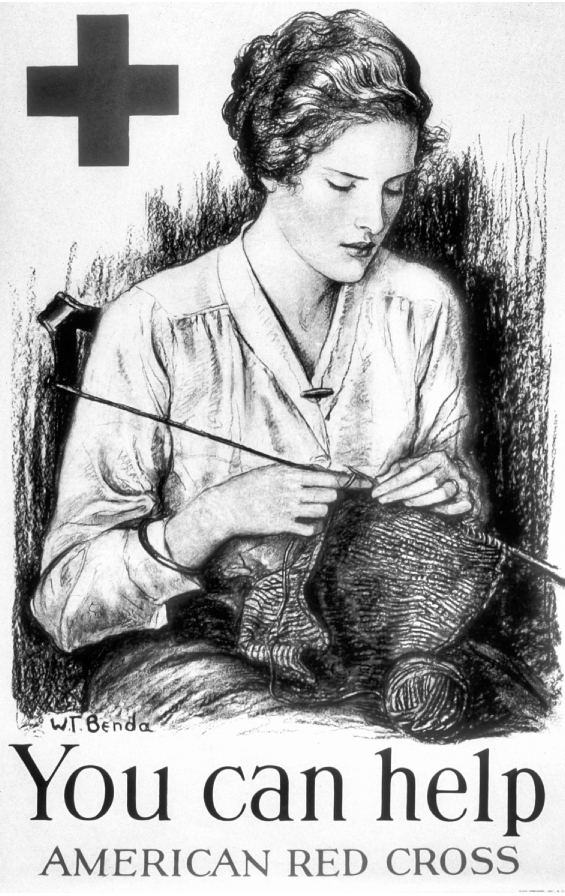

Cather portrays Enid in both ways. At times she seems reassuringly traditional, as when she sews her trousseau. Yet even such traditional female labor was frequently recruited for the war effort, as it is in W. T. Benda's "You can help" (fig. 1).[13] Even this modest activity, its legend suggest, can help win the war. Such images left women in the home but placed the home on the front line. In other words, they strike a fragile balance between traditional and new roles for women. Even as they assert women's place in the domestic sphere, these images covertly modernize, nationalize, and professionalize women's roles. Despite their traditional imagery, they contribute to an ultimately radical change in the way women's work could be understood. Such images were central to the processes of national incorporation that Claude finds so alienating and of which Cather's narrative at large seems so disapproving. Most negative in Cather's account is the extent to which such images covertly modernize traditional labor. Enid's execution of traditional women's work is problematically but surreptitiously modern. This makes her faults as a wife hard to see: "She managed a house easily and systematically. On Monday morning Claude turned on the washing machine before he went to work, and by nine o'clock the clothes were on the line. Enid liked to iron, and Claude had never before in his life worn so many clean shirts, or worn them with such satisfaction. She told him he need not economize in working shirts; it was as easy to iron six as three" (209). Enid's domestic labor is both mechanized and rationalized according to clocktime. Moreover, as if benefiting from the work place efficiency innovations of Fordism and Taylorism, more work simply makes Enid more efficient: it is "as easy to iron six shirts as three." But although Claude wears his shirts "with satisfaction," Cather portrays that pleasure as a poor substitute for the fulfillment of more primal desires.

Fig. 1. "You can help." Wladyslaw Theodore Benda. U.S.A. Black and

White, 20 × 30 inches. Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts

and Archives, Yale University Library.

Fig. 1. "You can help." Wladyslaw Theodore Benda. U.S.A. Black and

White, 20 × 30 inches. Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts

and Archives, Yale University Library.

The scientific domestic economy that defines Enid's housekeeping and cooking reflects the discourse used to mobilize women on the home front, in their kitchens, parlors, and gardens. One of Enid's most unsympathetic moments emerges directly from wartime educational propaganda aimed at women. The U.S. Food Administration used a series of posters to indoctrinate a primarily female audience into a new science of domestic economy. One poster in this series informs its viewer that unfertilized poultry eggs "last longer"[14] —a piece of scientific information that Enid puts to use by keeping her hens separate from the rooster. The neighbors, who prefer to do things the "natural" and "old-fashioned" way, disapprove of Enid's "fanatic" enforcement of sexual discipline and condemn her modern methods (203, 204). Through their remarks, Cather frames an essentially positive and empowering wartime script for women as one that makes them monstrous and unfeminine. Both Enid's scientific farming and her vegetarianism emerge directly from publicity disseminated as part of the war effort ("Eat Less Meat" and "Eat Less Wheat" were popular commands). In One of Ours, such traits take on negative connotations as the symptoms of Enid's retreat from sexuality and the body, which leaves Claude feeling sexually frustrated and underfed.

But Cather grounds Enid's lack of sympathy in other, less traditional

wartime images of women as well. In addition to collecting

money and goods, knitting for soldiers and refugees, and growing

and conserving food, women also participated in the war in

less "feminine" ways. Not long after the United States declared

war in 1917, the navy began enlisting women as a way of coping

with an intense demand for personnel (Gavin 1-24). In addition

to those who enlisted in the armed forces, many women were mobilized

by volunteer organizations such as the Red Cross, the Salvation

Army, and the YMCA and YWCA. According to historian

Susan Zeiger, "Women's work at the front was much more than a

simple extension of their participation in the civilian labor force. It

was also military or quasi-military service and therefore had profound

implications for a society grappling with questions about

the nature of women and their place in the public life of the nation,

in war and peacetime" (3-4). Questions about women's proper

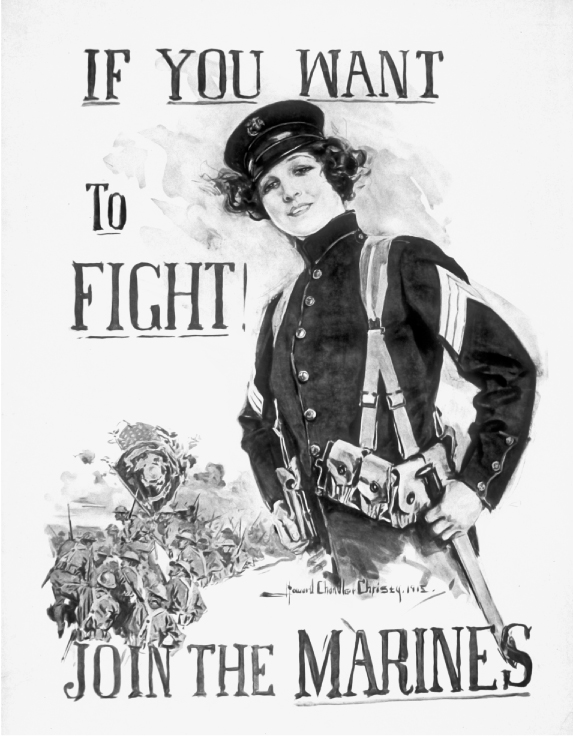

Fig. 2. "If You Want to Fight! Join the Marines." Howard Chandler Christy.

U.S.A. Color, 27 × 40. 1917. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale

University Library.

sphere repeatedly find their way into war posters, many of which

provide far from simplistic messages. Howard Chandler Christy

would repeatedly harness such questions in his poster illustrations

(see fig. 2, "If You Want to Fight!"). Christy clearly plays

with the possibility of women taking military roles. The image invites

a male viewer to assert his difference from the female figure,

whose male impersonation visibly fails. But the failure, I would argue, is not absolute:

Christy's female figure flirts with androgyny.

Christy's posters work primarily through an erotic charge generated

by woman-as-object, but they also allude to female independence.[15] This contradiction generates the posters' success. Posted

as a challenge, female ambition incites a male viewer to assert

his difference by doing things she cannot, such as enlisting. That

women ultimately were admitted to the navy and marines only

heightened the effectiveness of such images.[16] If the spectacle of

women simply contemplating men's work was an energizing one,

then their actually doing it could be pictured as an even more effective

challenge to men.

Fig. 2. "If You Want to Fight! Join the Marines." Howard Chandler Christy.

U.S.A. Color, 27 × 40. 1917. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale

University Library.

sphere repeatedly find their way into war posters, many of which

provide far from simplistic messages. Howard Chandler Christy

would repeatedly harness such questions in his poster illustrations

(see fig. 2, "If You Want to Fight!"). Christy clearly plays

with the possibility of women taking military roles. The image invites

a male viewer to assert his difference from the female figure,

whose male impersonation visibly fails. But the failure, I would argue, is not absolute:

Christy's female figure flirts with androgyny.

Christy's posters work primarily through an erotic charge generated

by woman-as-object, but they also allude to female independence.[15] This contradiction generates the posters' success. Posted

as a challenge, female ambition incites a male viewer to assert

his difference by doing things she cannot, such as enlisting. That

women ultimately were admitted to the navy and marines only

heightened the effectiveness of such images.[16] If the spectacle of

women simply contemplating men's work was an energizing one,

then their actually doing it could be pictured as an even more effective

challenge to men.

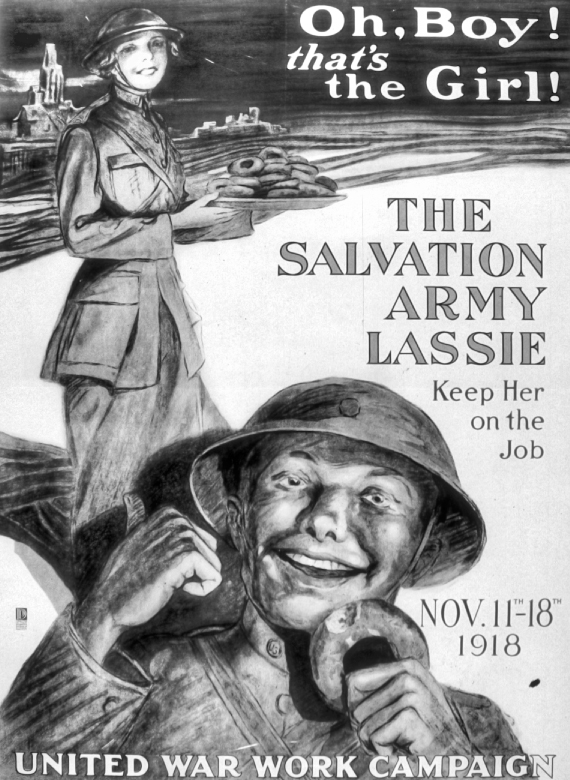

As women began to work near the front, this visual flirtation

with the possibility of women taking traditionally male roles in

the war effort became an increasingly dominant motif. Playful and

eroticized cross-dressing gives way to a more serious depiction of

women laboring in unfeminine circumstances. We catch a glimpse

of this in "The Salvation Army Lassie" (fig. 3). This poster plays

with the possibility of similarity between men and women, with

the possibility that women can replace or work as men. Part of

the pleasure of looking emerges as an interpretive game of comparing

and differentiating masculinity from femininity. "The Salvation

Army Lassie" ostensibly exemplifies a traditional version of

gender roles in wartime (since the "lassie" serves refreshments to

the men). She is in the poster's background, literally the girl behind

the man who fights the war. The male soldier stands in the foreground

and speaks for her. But the poster plays verbally and visually

with their similarity. Its text, "Oh, Boy! that's the Girl!," demonstrates

the arbitrary signification of words like "boy" and "girl."

The visual similarity between the figures—their khaki uniforms,

steel helmets, and youthful smiles—emphasize their likeness and

exchangeability. This poster gives visual shape to an actual gender

confusion surrounding the mobilization of women in France. The

presence of Salvation Army "lassies" was predicated on male dependence

on women and on a notion that women could contribute

in a fundamental way to the AEF's strength. Male soldiers, it

was argued, would naturally be homesick; and American women

could comfort them in a way French women, imagined as inherently

more sexual, could (or should) not. The Salvation Army,

Fig. 3. "The Salvation Army Lassie. Oh Boy! That's the Girl!" Anonymous.

U.S.A. Color, 30 × 40. 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale

University Library.

the Red Cross, and the hospitality services of the armed forces

took a good deal of care to supervise and desexualize the interactions

of American soldiers and their female support corps. The

kind of bond Salvation Army "lassies" like this one were supposedly

able to offer male soldiers was continually figured as a sibling

or maternal one. "American women . . . were expected to provide

the troops with a wholesome but winning distraction from

French prostitutes or lovers"; by their presence, American women

could comfort soldiers and help them observe the AEF's "policy of

sexual continence" against venereal disease (Zeiger 56). In other

words, women working at the front had to walk a thin line between

being feminine (comforting) but not too feminine (alluring)

—they had to enact their difference from soldiers while still being

their "chums."

Fig. 3. "The Salvation Army Lassie. Oh Boy! That's the Girl!" Anonymous.

U.S.A. Color, 30 × 40. 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale

University Library.

the Red Cross, and the hospitality services of the armed forces

took a good deal of care to supervise and desexualize the interactions

of American soldiers and their female support corps. The

kind of bond Salvation Army "lassies" like this one were supposedly

able to offer male soldiers was continually figured as a sibling

or maternal one. "American women . . . were expected to provide

the troops with a wholesome but winning distraction from

French prostitutes or lovers"; by their presence, American women

could comfort soldiers and help them observe the AEF's "policy of

sexual continence" against venereal disease (Zeiger 56). In other

words, women working at the front had to walk a thin line between

being feminine (comforting) but not too feminine (alluring)

—they had to enact their difference from soldiers while still being

their "chums."

Such imagery inflects Cather's portrait of Enid's asexuality. Enid refuses her husband as a sexual partner and often thinks of him as a brother or even a son. Cather's portrait recalls the deliberate desexualization of women war workers in France, who "were envoys of the American home front, representatives of the mothers, wives, and sisters left behind" but as such were represented in imagery that emphasized "sentimentality and homey comfort" over sexuality (Zeiger 57). Policies governing the recruitment of women (in the armed forces and in relief agencies) largely "excluded those with husbands in the war. . . . Organizations were looking for a special type of volunteer," who would not be "preoccupied with finding their loved ones" and who were "independent of familial and marital ties" (Chuppa-Cornell 469). In direct correlation, Enid describes herself as "not naturally drawn to people" and "free" to move abroad (131).

The official and conscious intent of assuring sisterly or maternal roles for women was to contain and discipline the threat of female sexuality, particularly the threat of its free expression outside the bounds of marriage. But this campaign to desexualize women's presence had an ironic result in that it gave form and coherence to a new kind of female independence that was equally, or perhaps even more, threatening. Certainly, Enid's lack of sexual desire is her most threatening quality, the one which makes her most unsympathetic to readers and critics—that is what exercises Sinclair Lewis in his review. The "Enid problem" is that Claude needs Enid but Enid doesn't want Claude: he needs a wife to make him the man of the house; he needs her care and her domestic labor as a grounding contrast to his masculinity; he needs their sexual relationship to bring his body's normative desires to the fore. But the very things that make Enid useful and necessary to Claude also make her strangely independent and unnaturally asexual.

Cather's description of this lack of traditional reciprocity evoke the new gender relations established during the war. Claude's need for Enid originally surfaces as a need for nursing. After Claude's accident in the barbed wire, she visits him every day, brings him flowers—reversing the traditional courtship ritual, as Rosowski notes (111)—and helps him pass the time while he convalesces. Enid's nursing activity conflates traditional femininity (providing support to men) with New Womanhood (lack of concern for decorum). If this conflation causes confusion to Mrs. Wheeler and to Claude—blinding them to Enid's lack of physical attraction to him and to her sexual unavailability—this too alludes to a constellation of fascination and anxiety that coalesced around the figure of the nurse during the war. The image of the nurse merged both feminine roles (nurturing) and masculine roles (being a new kind of soldier). We can see this in the ethical confusion provoked by the murder of Edith Cavell: Was she a civilian (a woman) or a soldier (a man)?[17] In killing her, did the Germans commit an atrocity on an innocent civilian woman or a justifiable act of war on the body of an enemy? "Total war" confused the gendered categories that war had traditionally enforced and made visible. Enid's role as a nurse invites us to see her as powerful and to see Claude, by contrast, as weak and ill, making it easy to read him (as Lewis does) as her victim. Cather makes Enid's nursing duplicitous and anxiety-provoking rather than admirable or courageous.

In this, Cather's novel resembles largely anxiety-ridden male-authored representations of nurses, rather than female-authored ones. Although she treats nursing rather briefly, her portrait predicts the nurse's popularity as a signal figure in the mediation of postwar gender anxiety. As I have argued elsewhere, several texts deflect anxiety about masculinity onto a sinister nurse figure, who heals wounded men only to entrap them in a painful and compromised life.[18] This trope of the dangerous nurse—a version of Lawrence's threatening "woman-saviour"—threads through fiction by male American modernists, notably William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. In A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway negotiates a war-triggered crisis of male autonomy through the body of a nurse. Hemingway takes the most feminizing aspects of male war experience (being a "little crazy" and dying a bloody death) and assigns them to Catherine Barkley. His narrative reinscribes the male body's vulnerability in wartime onto the otherwise powerful body of the nurse. The danger of professional independence that female nurses seem to pose is contained, or negated, by an old-fashioned lack of control over their bodies' reproductive capacities. Hemingway reembeds "nursing" in the biological context that the word's origin implies: female anatomy is destiny.

During the war, the profession of female nursing confounded gender difference by merging categories of soldiers and civilians and by reversing its opposite, the other popular plotline in propaganda: women in need of male rescue. Female nursing also raised questions of sexuality and propriety by bringing upper- and middle-class women into unsupervised, physical contact with soldiers. But if the nurse was a locus of anxiety about women's new independence in the hands of some postwar writers, the sexuality of female nurses also provided the means of restoring gender difference: feminine sexual weakness foils male independence. Cather's narrative does not provide the same comfort. She portrays the nurse as desexualized and, in consequence, dangerous.

Cather figures Enid's monstrously independent femininity most deliberately through another trope: the figure of the woman driver. This, the most explicitly negative sign of Enid's independence, is also the one that ties her most consistently to the war and to modernity. The figure of Enid at the wheel condenses these various aspects of Cather's narrative. Enid's skill as a driver first appears in a dramatic storm scene. After taking a day trip in the car, Claude and Enid find themselves seventy miles away from home with a storm coming up on the prairie. Claude suggests that they wait until the next day to drive home, but Enid refuses. This episode allows Cather to showcase Enid's "quiet"—and ominous— "determination": she "could not bear to have her plans changed by people or circumstances" (133). She exhibits a fearlessness that embarrasses Claude into acquiescence. But his unmanly caution seems justified when the storm arrives and he loses control of the car. He reiterates his suggestion that they seek shelter until the storm is over. Enid refuses, again, complaining that the nearby farm is "not very clean" and too crowded with children (134)— foreshadowing her "unfeminine" attitude toward domesticity. At that point, Enid herself takes the wheel. She insists that Claude is "nervous" (a watchword for effeminacy and for unmanly response to the pressures of war) and that she has more experience driving: "[Claude] was chafed by her stubbornness, but he had to admire her resourcefulness in handling the car. At the bottom of one of the worst hills was a new cement culvert, overlaid with liquid mud, where there was nothing for the chains to grip. The car slid to the edge of the culvert and stopped on the very brink. While they were ploughing up the other side of the hill, Enid remarked, 'It's a good thing your starter works well; a little jar would have thrown us over' " (134). Although Enid gets them home safely, Claude's manhood sustains some injury. On the very next page, Claude's accident occurs. The danger of injury, once averted, quickly returns, again tied to driving machines. Claude's accident with the truck and the mules in a sense reiterates the symbolic castration of his drive with Enid. His accident, along with his frustrated response to it, triggers his effeminizing illness and leads directly to his need for Enid's nursing—which leads, in turn, to the ultimate castration of their unconsummated marriage. Although Claude keeps Enid's sexual refusal a secret from his family and friends, her driving makes her physical abs(tin)ence visible to everyone: "Having a wife with a car of her own is next to having no wife at all," Leonard exclaims. "How they do like to roll around! I've been mighty blamed careful to see that Susie never learned to drive a car" (202). The scene of Enid's driving condenses everything unsympathetic about her: her determination, her inflexibility, her independence from Claude, her flight from domesticity and sexuality.

Embedded in a landscape of treacherous mud, Cather's portrayal of Enid's driving emerges directly from representations of women drivers for the war. Enid's driving establishes the fact that steely nerves and determination reside within an otherwise feminine and supposedly fragile body. Cather's portrayal seems indebted to images of war because it differs from the other dominant trends in the way that women's access to cars was pictured by the automobile industry and in other popular representations.[19] For instance, although most car advertisements before the 1920s picture women as passengers, Cather insists that Enid is the better driver. Contrary to other popular beliefs about how women would experience cars, Enid is not interested in the car as an accessory nor as a sign of status nor yet as a vehicle for unchaperoned sexual adventure (which is the fantasy implicitly keeping Leonard from letting his wife learn to drive—"How they do like to roll around!"). While most car advertisers imagined that women would want to drive short distances and that power and speed would be far less important to them than features of comfort and aesthetic appeal, Enid values the car for how it works, rather than for how it looks or feels to ride in. (Enid's appreciation of the car's self-starting mechanism suggests her technical understanding.) Finally, the episode underscores that Enid's primary interest in the car is as a vehicle for getting somewhere rather than as a pretense for being unchaperoned with her beau. The secluded and mobile privacy that the car made possible alarmed parents and others concerned with the morals of American youth; its speed and danger became a symbol, early on, for both sexual desire and female availability.

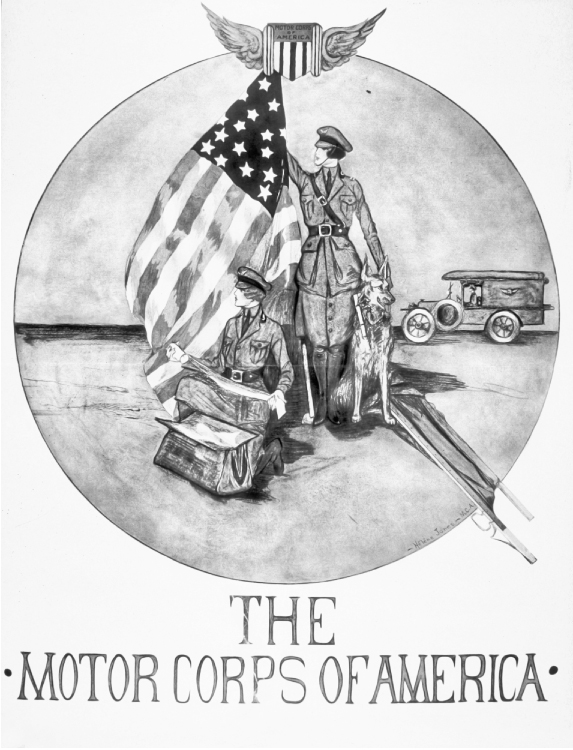

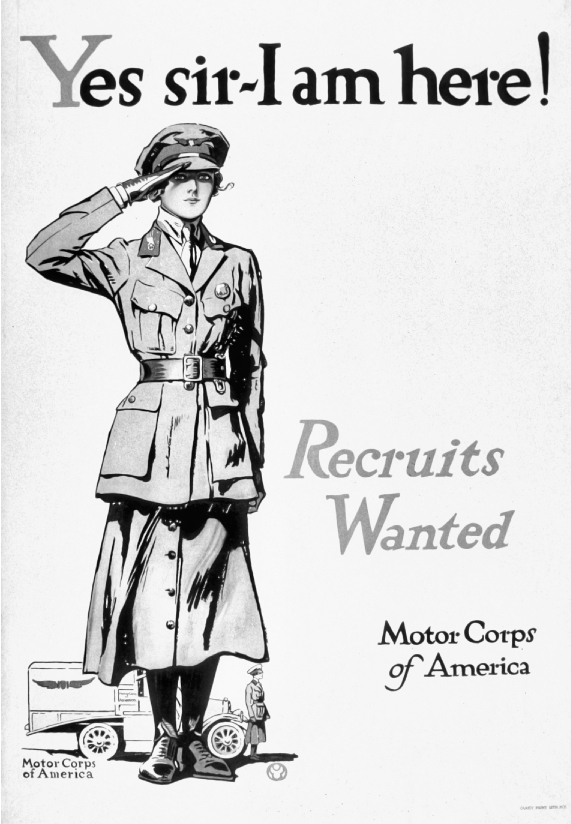

In all these particulars, Enid's driving resembles the professional attitude of women who served during the war under the auspices of various motor corps. Hélène Jones's "Motor Corps of America" (fig. 4) and Edward Penfield's " 'Yes Sir—I am Here!' Recruits Wanted Motor Corps of America" (fig. 5) show women working in uniform as agents in their own right. Rather than serving male soldiers who pose in front of them and speak for them, these female figures are pictured working independently or with other women. They handle machinery; they answer for themselves; they seem serious and professional rather than friendly and hospitable. Women who drove in France worked hard hours on bad roads, did their own maintenance, and worked alone close to the front.[20] These posters feature female figures with ambition, independence, and responsibility—all characteristics of Enid, who has a strong sense of her own personal mission for demanding labor in an international setting.

The femininity of these figures is ambivalent and hard to interpret:

we cannot tell if they have short cropped hair or the more

traditional long hair pulled back in a cap. While their uniforms

Fig. 4. "The Motor Corps of America." Hélène Jones. U.S.A. Color, 30 × 40 inches.

Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

mostly obscure their femininity, the Sam Browne belt—visible in

both images—accentuates both their feminine, narrow waists and

the fact that they are serving, like men, at the front (these belts

could only be worn abroad).[21] Their sex appeal is similarly ambivalent:

it emerges primarily from the challenge that their lack of

traditional femininity provokes. It is precisely this kind of

Fig. 4. "The Motor Corps of America." Hélène Jones. U.S.A. Color, 30 × 40 inches.

Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

mostly obscure their femininity, the Sam Browne belt—visible in

both images—accentuates both their feminine, narrow waists and

the fact that they are serving, like men, at the front (these belts

could only be worn abroad).[21] Their sex appeal is similarly ambivalent:

it emerges primarily from the challenge that their lack of

traditional femininity provokes. It is precisely this kind of

Fig. 5. "'Yes Sir—I am Here!' Recruits Wanted. Motor Corps of America." Edward Penfield.

U.S.A. Color, 27 × 40. Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives,

Yale University Library.

challenge that makes Enid such a treacherous figure. Enid's body both

draws and resists Claude's sexualizing gaze: "He wonder[s] why

she ha[s] no shades of feeling to correspond to her natural grace

. . . to the gentle, almost wistful attitudes of her body" (211).

Though she looks "wistful" to Claude, what she longs for is not

the reassuringly "natural" desires he imagines. For, Cather writes,

"Everything about a man's embrace was distasteful to Enid. . . .

[S]he disliked ardour of any kind" (210). Cather depicts Enid's

body—like the female figures in these posters—as wistfully feminine

but also efficient, Taylorized, even machinelike. Enid's body

works rather than reproduces. Enid has exactly what Claude feels

that he lacks as a man: she wholly identifies with a mission larger

than herself. Unlike Claude, and in a reversal of traditional gender

stereotypes, Enid does not need her raison d'être to be embodied

by another person. In contrast to the notion that women

develop strong social bonds and define their identity in social terms

rather than abstract ones, Cather describes Enid as "not naturally

much drawn to people," as perpetually "free" from intimate bonds

(131). Enid's ministrations to Claude after his accident, ostensibly

the sign of female service to men, signify precisely the opposite.

She cares for him because his accident gives her an opportunity

to enact, in a small way, her professional ambition of becoming

a missionary. Missionary work ultimately takes her, as it had her

sister Carrie (a name that evokes the dangers of female mobility in

early-twentieth-century fiction) to China.

Fig. 5. "'Yes Sir—I am Here!' Recruits Wanted. Motor Corps of America." Edward Penfield.

U.S.A. Color, 27 × 40. Circa 1918. War Poster Collection. Manuscripts and Archives,

Yale University Library.

challenge that makes Enid such a treacherous figure. Enid's body both

draws and resists Claude's sexualizing gaze: "He wonder[s] why

she ha[s] no shades of feeling to correspond to her natural grace

. . . to the gentle, almost wistful attitudes of her body" (211).

Though she looks "wistful" to Claude, what she longs for is not

the reassuringly "natural" desires he imagines. For, Cather writes,

"Everything about a man's embrace was distasteful to Enid. . . .

[S]he disliked ardour of any kind" (210). Cather depicts Enid's

body—like the female figures in these posters—as wistfully feminine

but also efficient, Taylorized, even machinelike. Enid's body

works rather than reproduces. Enid has exactly what Claude feels

that he lacks as a man: she wholly identifies with a mission larger

than herself. Unlike Claude, and in a reversal of traditional gender

stereotypes, Enid does not need her raison d'être to be embodied

by another person. In contrast to the notion that women

develop strong social bonds and define their identity in social terms

rather than abstract ones, Cather describes Enid as "not naturally

much drawn to people," as perpetually "free" from intimate bonds

(131). Enid's ministrations to Claude after his accident, ostensibly

the sign of female service to men, signify precisely the opposite.

She cares for him because his accident gives her an opportunity

to enact, in a small way, her professional ambition of becoming

a missionary. Missionary work ultimately takes her, as it had her

sister Carrie (a name that evokes the dangers of female mobility in

early-twentieth-century fiction) to China.

What makes Enid so monstrous is her lack of need for a man. She does not need a masculine partner against whom her own femininity can cohere in contrast. Enid never seems as tormented by her lack of traditional femininity as Claude is by his failure to be a "normal" man. Her lack of sexuality aligns her with Claude's castrating father because she withholds and forbids what Claude imagines he needs to make his manhood real in the world. It would be possible to read this as lesbianism, and yet Cather figures the danger the New Woman poses not as undisciplined desire but as erotophobia.[22] Enid's monstrosity exists not in her appetites but in her lack of them: she's a virgin, a teetotaler, and a vegetarian. She's not pictured as overly or voraciously feminine but instead as androgynous and autotelic. Like one of Lawrence's "women saviours," Enid drives herself to save the world. That drive makes her an unfit wife, one who wounds her husband and who is perceived as posing a general threat to men and male homosociality: "Within a few months Enid's car traveled more than two thousand miles for the Prohibitionist cause"—a cause which leaves Claude home alone and alienates him from his male friends (209).

Having depicted this dangerous New Woman, Cather banishes her from the novel. Enid takes the dangers posed by modernity with her and makes the war "safe." Before Claude goes off to war, Enid goes off to China, and his masculine crisis disappears with her. Once she's gone, machines no longer seem to pose the same threat. Treacherous mud and lacerating barbed wire only seem to threaten Claude when Enid is nearby. In comparison with the "queer," disfiguring, and infection-prone wounds Claude receives at home, Cather describes his war wounds as "clean" (453).

Indeed, even the automobile—which Cather describes elsewhere as "misshapen and sullen, like an ugly threat in a stream of things that were bright and beautiful and alive"[23] —can be recuperated once Enid is no longer at the wheel. Toward the end of the novel, Cather suggests that the automobile will provide postwar consolation to men: "What Hicks had wanted most in this world was to run a garage and repair shop with his old chum, Dell Able. Beaufort ended all that. He means to conduct a sort of memorial shop, anyhow, with 'Hicks and Able' over the door. He wants to roll up his sleeves and look at the logical and beautiful inwards of automobiles for the rest of his life" (456-57, italics added). If cars had once been vehicles of castration, Cather associates them here with healing, and with male agency ("Able"). Similarly, while Enid's driving isolates Claude, postwar driving will bring men together: "Though Bert lives on the Platte and Hicks on the Big Blue, the automobile roads between these two rivers are excellent" (456).

The negative aspects of modernity disappear with Enid. Interestingly, Cather suspends her portrayal and judgment of the character at that point in the narrative. She never disciplines Enid within the plot itself, which may be why critics like Lewis felt the need to condemn the character so vociferously. The fact that Enid disappears does not, of course, mitigate the misogyny of Cather's portrait. Instead, Cather's suspension of discipline makes itself felt as the "thing not named" in the text, and in turn engenders the tradition of name calling (Enid is "an evangelical prig who very much knows what she doesn't want") that so many critics have relished.

In an ironic way, then, the novel authorizes the misogyny that has marked its critical reception, in its own time and in later decades. Cather's novel received criticism when it was published not only because it offered a heroic version of the war but because Cather was a woman writer. H. L. Mencken broaches this criticism in a rather subtle way, by comparing her novel, to its detriment, with John Dos Passos's "bold realism" in Three Soldiers (1921): What spoils [Cather's] story is simply that a year or so ago a young soldier named John Dos Passos printed a novel called Three Soldiers. Until Three Soldiers is forgotten and fancy achieves its inevitable victory over fact, no war story can be written in the United States without challenging comparison with it. . . . At one blast it disposed of oceans of romance and blather. It changed the whole tone of American opinion about the war; it even changed the recollections of actual veterans of the war. They saw, no doubt, substantially what Dos Passos saw, but it took his bold realism to disentangle their recollection from the prevailing buncombe and sentimentality. . . . The war [Miss Cather] depicts has its thrills and even its touches of plausibility, but at bottom it is fought out, not in France, but on a Hollywood movie-lot. (O'Connor 142) The opposition Mencken sets up between the "young soldier's" view of the war and that offered by "Miss Cather" hinges on their gender and the access that gender supposedly provided to the war. He offers this critique in literary terms but in literary terms that inscribe gender: a "blast" of "bold realism" versus "fancy," "oceans of romance and blather," "buncombe and sentimentality." Hemingway, famously, offered a much more explicit attack on Cather as a woman who dared to write about male experience.[24]

The same kind of identity politics that characterize these early criticisms long continued to define the parameters of discussions of One of Ours. In his 1967 World War I and the American Novel, Stanley Cooperman's analysis of One of Ours and the war fiction of Edith Wharton justifies his conclusion that women cannot represent war. Both authors earn Cooperman's disapproval for "sentimentality and intrusive rhetoric"—for being too propagandistic and for offering a romantic view of the war (129). He reiterates what Hemingway had written and assumes that, as a woman, Cather "knew very little about the war she was describing" (136). But if One of Ours seems spurious to some for being a female-authored war novel, it has also proven somewhat intractable to feminist reevaluations of Cather and her work. The novel's misogyny disrupts the neatness of Sharon O'Brien's description of Cather's progress as a woman writer in Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice. Cather published it years after having, as O'Brien articulates so well, replaced an early identification with men and male authors with a feminine aesthetic. In other words, in One of Ours Cather expresses what seems like an atavistic doubt and dread about femininity. This contributes, I think, to the comparatively little attention the novel has received among Cather scholars. Too "womanly" for some, not "womanly" enough for others, the novel long continued both to provoke and to betray a desire for coherent and predictable differences between masculinity and femininity.

Rather than offering a psychological account of the sexual and gender conflicts Cather as an individual may have been working out in One of Ours, I want to conclude by considering the novel's use of gender to organize what was an extremely confusing and painful cultural experience. The deepest insight of Mencken's review of the novel comes in the form of his admission that people needed help ordering their "memories" of the war and in the ongoing postwar process of determining what it had meant: "[Dos Passos's novel] changed the whole tone of American opinion about the war; it even changed the recollections of actual veterans of the war," he writes (142, italics added). If "actual" witnesses of the war could change their "recollections" of what happened there, then the mutability of visions of more distant observers is hardly surprising. Recollections and fictions about the war, then, continued to be the vehicle for the negotiation of conflict. Telling the story of the war offered individuals and the culture at large ways to debate how to value the violence suffered and inflicted in the name of manhood and the nation and how to judge the nation that had demanded such sacrifice in such terms.

Misogynistic representations of the war testify, then, not simply to cultural (or personal) attitudes about women but to the depth of anger and resentment that followed the experience of war, even among the so-called victors. The need to find a scapegoat overwhelmed many level-headed and well-meaning attempts to account for and remember the war. Coming to terms with its costs —particularly the human costs—was difficult. The unprecedented losses of World War I provoked a crisis in cultural mourning practices, which in turn triggered a variety of postwar rituals and narratives, both innovative and traditional. Holding women responsible for the war was only one of several responses. The difficulty of telling the story of the war made that story porous: it repeatedly absorbed and was used to formulate other anxieties and conflicts. Cather's war novel encodes a melancholic and nostalgic desire for the past, for a time before the war, and a for a time when some, including Cather and her character Claude, had "hoped extravagantly" to win a fight against modernity (459).