From Cather Studies Volume 6

Willa Cather's Civil War

A Very Long Engagement

Willa Cather's story "The Namesake" was published in 1907, soon after her move to New York City as an editor of the influential McClure's Magazine. With a volume of poems and one of stories published and a career at the center of American literary and publishing culture opening up in front of her, Cather appears in this story to be thinking about what makes an artist "American," about what an American artist's resources are. In the story a group of young, male American artists gather in Paris around a successful sculptor, Lyon Hartwell, who seems to epitomize what it means to be an American artist: "to mean all of it, from ocean to ocean" (137). To these young men, who have come from various U.S. locales (but not from the South, where Cather was born), a Paris studio is the place where they imagine that they can become players in the exhilarating game of American art in which Hartwell is so brilliantly succeeding. "Never had the game seemed so enchanting, the chance to play it such a piece of unmerited, unbelievable good fortune" (138). Hartwell's success has been built on a series of iconic images of male heroism drawn from the continuum of U.S. history; he has "thrown up in bronze all the restless, teeming force of that adventurous wave still climbing westward in our own land across the waters . . . his Scout, his Pioneer, his Gold Seekers, and those monuments in which he had invested one and another of the heroes of the Civil War with such convincing dignity and power." The height of Hartwell's achievement is his latest work, The Color Sergeant, which will be "cast in bronze, intended as a monument for some American battlefield. . . . It was the figure of a young [Union] soldier running, clutching the folds of a flag, the staff of which had been shot away." The figure is full of "splendid action and feeling" (139). The description of Hartwell's work emphasizes that he has achieved both artistic and marketplace success, tapping into postbellum America's appetite to memorialize its own legendary (and recent) history, particularly through the monumental sculpture that commemorated the Civil War.[1]

For the aspiring acolytes who cluster around Hartwell in his Paris studio, expatriation seems one of the rules of the game, and a summons "home" to America, such as one of their number has received, is a disaster that threatens their status as artists. Hartwell responds to his young friend's departure with a story about his discovery of his own U.S. "citizenship" as a source of his deepest feelings and his art, as expressed in The Color Sergeant. He was born in Italy, son of an expatriate father and a mother who died early and had no acknowledged influence on her son. His father was an unsuccessful sculptor ("I dare say you've not heard of him") who remained in Rome until his death, "chipping away at his Indian maidens and marble goddesses, still gloomily seeking the thing for which he had made himself the most unhappy of exiles." When the Civil War broke out, he did not return home to Pennsylvania to enlist in the Union army, and was thus considered a "renegade" by his family (140). For Hartwell, his father seems to embody the dark side of expatriation, and his conventional female subjects cut him off from the sanctioned narrative of U.S. male heroism. He is the problematic noncombatant ancestor—and yet Hartwell is clearly the beneficiary of his father's ambitions and profession and of the Roman education that his father decreed for him.[2]

As a young man whose career as a sculptor was just beginning to flourish, Hartwell

was also

summoned back to the United States by family duty: his father's sister, nearly helpless

from a "cerebral disease," needed his care. At the lonely family house the only connection

he feels is to a portrait of a dead uncle for whom he was named but never met. This

namesake enlisted in the Union army at fifteen and died as a color sergeant bearing

the flag a year later. Since the aunt can summon up few memories of her soldier brother,

who is buried in the orchard, Hartwell pieces together the story of his brief career

and heroic death from "an old soldier in the village" and a comrade's newspaper account

of the boy's death. Hartwell also begins to read Civil War history in books collected

by his grandfather. To Hartwell, this uncle—whose name he shares and whose identity

thus seems to be entwined with his own—"seemed to have possessed all the charm and

brilliance allotted to his family and to have lived up its vitality in one splendid

hour" (143-44). Then, in response to the stimulus of a powerful national impulse—Decoration

Day on May 30, an observance that began in 1865 and grew to an important national

ritual of Civil War remembrance by the late nineteenth century—the aunt rouses herself

to commemoration: she instructs Hartwell to run up the "big flag" on the uncle's grave

and goes with him to decorate the grave with "garden flowers" (see fig. 1). That day,

Hartwell at last discovers the trunk—marked with the name they share—in which the

dead boy's mother packed away her son's belongings: clothing, toys, war letters, and

a textbook embellished with his childish drawings of military paraphernalia, a "Federal

flag" and lines from the national anthem. Clutching this book, which suddenly gives

him the sense that he "knows" his uncle, Hartwell spends the night sitting at the

soldier's grave, as the flag tosses above him in the dark. It is a rending, overwhelming

experience:

It was the same feeling that artists know when we, rarely, achieve truth in our work;

the feeling of union with some great force, of purpose and security, of being glad

that we have lived. For the first time I felt the pull of race and blood and kindred,

and felt beating within me things that had not begun with me. It was as if the earth

under my feet had grasped and rooted me, and were pouring its essence into me. I sat

there until the dawn of morning, and all night long my life seemed to be pouring out

of me and running into the ground. (146)

Hartwell has found his "citizenship," the other half of his inheritance, the meaning

of his name,

and his nationality. For the first time in his life he feels rooted, tied by kinship

and by passion

to a national and familial tradition that is not purely personal: "things that had

not begun with

me." The earth, which contains his uncle, asserts its claim on him, "pouring its essence"

into

Hartwell,  Fig. 1. This turn-of-the-century postcard

commemorates Decoration Day with some of the iconography that had become associated

with that

holiday, established to honor Civil War dead. The central wreath is a conventional

tribute to

heroism, and the U.S. and Confederate flags are of equal size and importance, suggesting

that both armies are honored. The flags become the clothing of the central young

woman, implying that memorializing is a female task. Ruth Rogers Romines Collection,

courtesy of the author.

Fig. 1. This turn-of-the-century postcard

commemorates Decoration Day with some of the iconography that had become associated

with that

holiday, established to honor Civil War dead. The central wreath is a conventional

tribute to

heroism, and the U.S. and Confederate flags are of equal size and importance, suggesting

that both armies are honored. The flags become the clothing of the central young

woman, implying that memorializing is a female task. Ruth Rogers Romines Collection,

courtesy of the author.

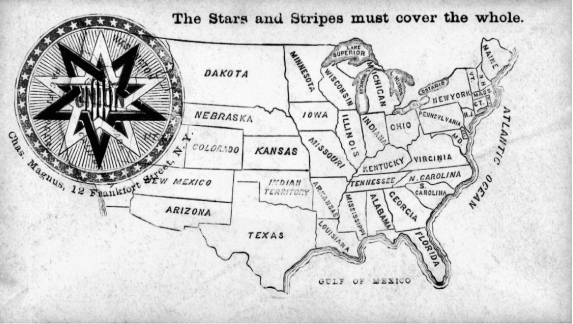

Fig. 2. This commemorative envelope, printed in New York City during the Civil War

years underlies the importance of the U.S. flag ("The Stars and Stripes must cover

the whole" map of U.S. territories and states—even the seceded states) and of UNION,

the word emblazoned across the red, white, and blue star at upper left. Collection

of the author.and he responds in kind, in imagery that suggests both semen and blood, both life

and death, as his life "seemed to be pouring out of me and running into the ground."

For Hartwell, this is not only an experience of discovering and acknowledging family

and national connections; it is also his making, as a specifically American artist.

Fig. 2. This commemorative envelope, printed in New York City during the Civil War

years underlies the importance of the U.S. flag ("The Stars and Stripes must cover

the whole" map of U.S. territories and states—even the seceded states) and of UNION,

the word emblazoned across the red, white, and blue star at upper left. Collection

of the author.and he responds in kind, in imagery that suggests both semen and blood, both life

and death, as his life "seemed to be pouring out of me and running into the ground."

For Hartwell, this is not only an experience of discovering and acknowledging family

and national connections; it is also his making, as a specifically American artist.

Federal language emphasized that the Civil War was fought to "preserve the Union." A typical bit of ephemera from the Civil War years, a decorated envelope printed in New York, is emblazoned with a red, white, and blue star with "UNION" at its center, superimposed on a map of the entire United States, including the seceded states. Above is this legend: "The Stars and Stripes must cover the whole" (see fig. 2). The language that describes Hartwell suggests these same Union priorities: as an artist, he means "all of it," the whole nation "from ocean to ocean" and the "adventurous wave" of its settlement and defense. When his work succeeds in achieving "truth," Hartwell says, he has a "feeling of union." As an artist, then, he can memorialize both his uncle and the cause for which the young color sergeant died, "with the flag settling about him" (176). On many levels, Hartwell has found a way, through his art, to preserve the Union. And yet he does so as an expatriate American artist, living out the legacies of both the soldier uncle and the noncombatant father.

In her sympathetic portrait of Lyon Hartwell, Cather invented an American artist born in 1854 who was able to draw sustenance from both a native and an expatriate heritage and whose art responds powerfully to the national priorities of his time, of which a central event was the Civil War. As David W. Blight writes, "The most immediate legacy of the war was its slaughter and how to remember it" (64). This legacy of loss and memory created Hartwell's market—all those battlefield monuments—and his private/public epiphany is occasioned by a national observance, Decoration Day. According to Blight, "Decoration Day, and the ways in which it was observed, shaped Civil War memory as much as any other cultural ritual" (65). In addition, as he sought his namesake's story, Hartwell participated in other memorial rituals that Americans observed in the years after the war: he heard and read stories by veterans; he studied Civil War histories; he examined the relics of the dead soldier preserved (as was customary) by his female relatives. Participating in such rituals, and producing art that will become a part of them, Hartwell—even though he is in France—can achieve a powerful (and lucrative) union with his culture.

As we read the narrative of Cather's career, "The Namesake" might first seem to reveal a thirty-some-year-old writer examining a model for her own career as American artist, and in particular claiming the Civil War and its remembrance as a subject. In fact, few American writers of her generation so fully owned that subject, by inheritance, as Cather. Her father, Charles Cather, and her paternal uncle, George Cather, had been noncombatants in the war. The Cather family, living in Frederick County in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, a region that saw heavy and constant combat, supported the Union cause. The two sons briefly moved into West Virginia near the war's end, to avoid the Confederate draft, but neither joined the Union army. (Cather's father was only seventeen when the war ended.) However, Cather's three maternal uncles all joined the Confederate army, and one of them died in 1862, at nineteen, of wounds received at Second Manassas.[3] Cather's mother, Mary Virginia Boak Cather, and her maternal grandmother, Rachel Seibert Boak, told stories of this family war hero, and his sword, uniform, and a Confederate flag were preserved as family relics. Civil War stories from both sides of the family—the Union Cathers and the Confederate Boaks—were a staple component of Cather's childhood and adolescence, both in her Virginia birthplace and later in Nebraska, and a famous photograph of adolescent Cather in a Confederate cap suggests that she may have used the family relics to enact such stories herself. In some ways, Cather's own inheritance replicates Hartwell's, with combatant and noncombatant ancestors, relics of a dead hero preserved by loving women, and a repertoire of war stories in fact far more extensive than the expatriate Hartwell's.[4]

A few years before the story "The Namesake," Cather had published a poem of the same title, which was closer than Hartwell's story to her own family legacy. In it, a somewhat androgynous young speaker stands at the grave of a young uncle, a Confederate war casualty, whose name he bears[5] . The speaker resembles the dead soldier ("with hair like mine") and, in ringing couplets, he expresses his eagerness to share the hero's military life ("help you hold your gun") and death, leaving his "girl" behind to share the soldier's "bed of glory," a grave. However, this young speaker is no self-abnegating mourner, caught up in a death wish—instead he looks toward his own future, aiming to "be winner at the game / Enough for two who bore the name." He intends to be a player, and he is drawn to "the game" as powerfully as are the young artists who cluster around Hartwell in Paris.

Cather's poem, when originally published in 1902, had this dedication: "To W.L.B., of the Thirty-Fifth Virginia." As Bernice Slote observes, "W.L.B. could refer only to Cather's maternal grandfather, William Lee Boak [who had died well before the war, in 1854], and, like the 'Thirty-Fifth' was clearly an error that was corrected in 1903," with publication in April Twilights, to "To W.S.B. of the Thirty-Third Virginia" (55). Cather's biographers have assumed that this corrected dedication refers to her dead Confederate uncle, William Seibert Boak, who was indeed a member of "the Thirty-Third Virginia." However, that uncle's name was actually James William Boak, as his military records and tombstone confirm. (Another Confederate uncle was Jacob Seibert Boak, but he survived the war.) Apparently young Cather was confused about some of the details of her family's Civil War history and her own Confederate genealogy when she made this slight but telling alteration in her uncle's name. Also, by this time she had adopted "Sibert" (an alternate spelling used by some family members) as her own middle name. She would continue to be Willa Sibert Cather professionally until mid-career and personally until the end of her life. So she needed a namesake with the Seibert name. In addition, Cather had been called "Willie" by family and close friends since babyhood. One source for the nickname was her female namesake, paternal aunt Wilella Cather, who died of diphtheria in 1869 at the age of four; Wilella too had been called "Willie" by the Cather family. (Cather herself had changed her given name from "Wilella" to "Willa" when, as a child, she altered the inscription in the family Bible.) But "Willie" may have honored her mother's dead brother, James William, who was also called by that nickname, as well as her father's dead sister. The fact that Cather, early in her career, produced two works titled "The Namesake" suggests that an identification with a namesake was a special issue for her, and one that linked her to the Civil War.

Of the two works, the 1907 story is the more rich and complex; it foreshadows Cather's great fiction to come. But it also implies—if one reads autobiographical elements in both poem and story, as most critics have—that Cather is revising away some of the complications of her actual genealogy as it was reflected in her name. "Wilella/Willa/Willie" suggests a name both inherited and chosen, with androgynous possibilities. "Cather" ties her to her paternal tradition of noncombatant support of the Union cause. And by adding "Sibert" to her name, she evoked her slave-owning Virginia Seibert ancestors and her ties to her beloved Confederate Grandmother Boak (who was born a Seibert), as well as the Confederate soldier. To make the Civil War ancestor a Union soldier eliminates most of these conflicting loyalties and makes possible Hartwell's personal and artistic act of union with the dead soldier, a union that advances his career—as the publication of the story in a major national magazine, McClure's, may well have advanced Cather's career[6] . As Lisa Marcus has suggested, "Perhaps Cather, more cosmopolitan and worldly in 1907, recognized that her dedication to her dead Confederate relative was problematic" (108). In her story, Cather proposed a model for Civil War art that seemed to promise success in the early-twentieth-century market where she was positioning herself and to offer options for writing some of the Civil War stories that were part of her own rich legacy.

However, as we know, those stories did not follow. Instead, the Civil War is remarkably absent from Cather's oeuvre until her last novel, published in 1940. Sapphira and the Slave Girl spans the years between 1856 and 1881, and it is set in Cather's ancestral Virginia (one of the most heavily contested areas of the war), where she spent her first years, 1873-83. Here, at last, was Cather's Civil War novel, following closely upon such notable Civil War fictions as Absalom, Absalom! and Gone with the Wind, both published in 1936, the year that Cather began to write Sapphira. But this Civil War novel is one without battle scenes or youthful male heroism of the sort celebrated in The Color Sergeant. Nor does it feature exhausted women such as Hartwell's aunt, wasted in body and in memory, for whom Decoration Day—devoted to Civil War memories—is the most important day of the year, or elderly male veterans full of war stories, such as the one who tells Hartwell about his uncle. In Cather's novel, all these saleable staples of Civil War art are notably absent. In fact, the war itself is absent; Sapphira comprises 269 pages set on a slaveholding Virginia plantation/farm in 1856, followed by a 20-page epilogue set twenty-five years later. The war years are a powerful absence at the center of the book.

Cather had been a child of Reconstruction, born eight years after the war's end. According to Bertram Wyatt-Brown, "When the Civil War came to its bloody end, the white people of the Confederacy felt the shame of defeat, a sense of profound hopelessness, and a fear of the future" (230). Reconstruction measures established Union martial law in the South; these measures required the rewriting of state constitutions to accommodate the changed legal status of African Americans, attempted to broaden the bases of public education, and encouraged economic recovery. But, as Joseph M. Flora has written, in the South this "Reconstruction history was readily subsumed under the myth of Reconstruction that portrayed Reconstruction efforts as totally wrong and resulting in state governments . . . composed of Negroes ill-prepared for office, 'carpetbaggers,' . . . and 'scalawags'" (727). Southern historians William J. Cooper and Thomas E. Terrill add that white "Southerners came to view Reconstruction as a Tragic Era" and "salved wounds of defeat and feelings of massive wrong with this and other legends: the Lost Cause . . . the Old South" (383, 389). As a child in a postwar white Southern family, Cather was the particular target of this mythology; if it was to survive (as it did), children of her generation would need to absorb and perpetuate it. Many Southerners—particularly women—organized to combat the "intrusions" of Reconstruction with educational projects aimed specifically at white children (Clinton 182-84). And, as a female relative of men who had fought for the Confederacy, Cather inherited the obligation to memorialize them (as she did in her poem "The Namesake") and the cause for which they fought—another postwar women's project that was especially prominent in Virginia, where there are 223 Confederate memorials, more than in any other state.

Frederick County had suffered severely in the war. It was considered "mandatory for the Confederacy to hold this region that . . . was bountifully productive of . . . wheat, beef, leather, horses, cloth—but also was strategically placed and shielded by the Blue Ridge so that a Confederate Army in Winchester and the northern [Shenandoah] Valley would always threaten not only Washington but also Maryland and Pennsylvania" (Colt 8). Thus the county's major town, Winchester (only eleven miles west of the Cathers' home in Back Creek Valley), "from the summer of 1861 through the fall of 1864 . . . knew the occupation or threatening proximity of one army or the other." No other town of this size saw so much action during those four years (Colt 8-9). Although many Frederick Countians had been Union sympathizers at the war's beginning, by its end, "the majority of citizens were firmly aligned with the South, primarily because of the harsh treatment they had received from Union troops" (Kalbian 73). After Appomattox, Frederick County's Confederate soldiers "came home to a wasteland—no trees, no fences, no barns, no mills. . . . A great many people had invested their all—what was not in the ravaged land—in Confederate money and bonds. There was no remaining capital to fuel new enterprises" (Colt 19).

In this climate the noncombatant, Unionist Cathers fared better than many of their neighbors. Their home, Willow Shade, was not significantly damaged, and they had not lost sons or property or suffered severe financial reverses during the war, as many of their neighbors had. After the war, Cather's grandfather, William Cather, was appointed sheriff by the occupying Union troops; he hired his own sons and nephew as deputies, and the family remained financially stable. There are persistent rumors that this good luck was resented in Back Creek Valley. In 1872 members of the William Cather family began to emigrate to Nebraska, seeking better crops, financial opportunity, and a healthier climate for daughters who suffered from tuberculosis. Cather's young parents, Charles and Mary Virginia, along with Grandma Boak, remained in Frederick County and ran the profitable family sheep farm at Willow Shade—until 1883, when their sheep barn burned (there were rumors of arson). Within a few weeks, the family moved to Nebraska; Cather was nine years old. As recently as 1952 a Frederick County woman claimed that the Charles Cather family "left this country and moved to Red Cloud because of some mean low down gossip" (Hannum)—possibly suggesting that Reconstruction tensions spurred their removal.

During Cather's childhood in Frederick County, so recently embattled, among persons who had experienced the conditions of war at close hand, stories of the war and the circumstances that preceded it were a cultural staple. And in the Cather household, most of the storytellers appear to have been women. Mary Virginia Boak told stories of her Confederate brothers, particularly the dead one. Marjorie Anderson, the family servant in both Virginia and Nebraska, had several brothers in the Confederate army; she is evoked as Mahailey, a teller of Virginia war tales, in One of Ours (Lewis 11-12). A favorite great-aunt, Sidney Cather Gore, prototype for the abolitionist Mrs. Bywaters in Sapphira, hid soldiers from both armies in her "rambling garrets" (Sapphira 274); Cather surely heard such stories from her, as well as from both her grandmothers. In a 1969 interview, Cather's Red Cloud friend Carrie Miner Sherwood—then almost one hundred years old—recalled the stories told by Rachel Boak, who died in 1893:

We were just as fond of Grandmother Boak, Willie's maternal grandmother, as the Cathers were. She was a little Southern lady who had lived through the war. She held us spellbound with first-hand accounts of the Civil War. As I remember it [incorrectly], she had sons in both armies.

We loved to have her tell and retell about the time the soldiers took possession of their home near Shenandoah [sic], Virginia. And how, at night, she would go with supplies for the boys to the Confederate camp, and the following night take supplies to the Union camp. (Hoover 150)

In a letter to a friend at the time of Sapphira's publication, Cather also said that the stories told by her Grandmother Boak and by "Aunt Till," a former slave who had belonged to Rachel Boak's parents, provided her understanding of antebellum Back Creek Valley (Cather to Dorothy Canfield Fisher).

So it seems apparent that much of the material for Cather's Civil War novel was a product of the Reconstruction years and those that immediately followed and the patterns of storytelling—both private and published—that those years produced. One of the earliest and most successful of Southern writers from those years was a Shenandoah Valley veteran and novelist, John Esten Cooke, whom Cather's parents presumably admired: his books were in their library, and they named one of their sons John Esten Cather. Cooke wrote from a romantic Confederate perspective, celebrating such Shenandoah Valley heroes as Stonewall Jackson and Turner Ashby, and he developed a national audience. According to Blight, "Combining literary ambition with a genteel Lost Cause outlook, Cooke demonstrated that some soldiers were ready early to refashion war memories into cultural and political dividends" (157)—dividends such as Cather celebrated in Hartwell's Civil War sculpture. By the 1880s, Blight argues, "reconciliation" was the desired theme of Civil War literature for both Southern and Northern readers. "The war was drained of evil, and to a great extent, of cause or political meaning." For the most part, "the ideological character of the war, especially the reality of emancipation, had faded from American literature." Such a literature denied "that the war and its aftermath were all about race" (215, 217, 221). Even such a masterly psychological study of the war as Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage (1895) shared this ideological emptiness—as did Hartwell's The Color Sergeant.

Coming of age in the late nineteenth century as an artist, and as an artist who might write about the Civil War, Cather must have been bombarded with conflicting precedents. From Rachel Boak and "Aunt Till," she heard of the "slave girl" Nancy's cruel harassment and difficult escape—as well as Till's hagiographic tales (very much in the romantic "faithful slave" mode) of the "Master" and "Mistress" who owned Nancy and Till herself. Were the postwar years—when Nancy memorably returned to Back Creek Valley for a reconciliatory visit—a period of calm and reunion, or of angry tensions that may have helped to precipitated the Cathers' departure for Nebraska? "Lost Cause" ideology would have pushed Cather to memorialize Southern heroics, as epitomized in the soldier-uncle of her poem, while the national market for benign "reconciliation" would have enjoined her to drain ideology—and particularly issues of race—from Civil War art. No wonder that, after the publication of her two versions of "The Namesake," Cather eschewed the Civil War for thirty years!

When Cather began to write Sapphira, she was sixty-three and an established major "player" in the game of American letters. At that point she was more than ready to set her own priorities. Perhaps the most striking feature of her 1940 Civil War novel is that it contradicts most of the precedents that might have constrained her in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The major portion of the novel, set in 1856, foreshadows the coming war in Sapphira and Henry Colbert's slaveholding household. As Henry agonizes over whether slavery is morally (and religiously) justifiable and whether his marriage vows obligate him to keep his wife's human property enslaved, the invalid Sapphira becomes jealous of her husband's obvious attachment to the innocent "slave girl" Nancy and invites a sexually predatory nephew, Martin, for a long visit, with the apparent hope that he will rape Nancy. Meanwhile, Sapphira and Henry's adult daughter, Rachel, who has opposed slaveholding since her childhood, decides (with the help of local Quaker connections to the Underground Railroad) to help the terrified Nancy escape to Canada. Nancy leaves without saying a word about her intentions to her own mother, Till (Sapphira's most trusted slave), or to anyone else in the slave community, and proud Till is reduced to surreptitiously asking Rachel about her own daughter's welfare. Surmising Rachel's aid to Nancy, Sapphira cuts off relations with her daughter. They are partially, formally reconciled only when Rachel loses one of her young daughters to diphtheria and Sapphira is so ill that she needs her daughter's constant attendance. The minute Sapphira dies, Henry frees all her slaves (he had offered to free his capable assistant, Sampson, earlier, and Sampson refused the offer, preferring the security of his life as a slave).

In this trenchant plot, Cather shows how the institution of slavery blights white and black family and marital relations, invoking the sexual anger of white women who observed or suspected white men's sexual relations with slave women and resultant mulatto children, like Nancy, as well as the family splits that were exacerbated by the war, especially in border regions like the northern Virginia county where Cather's family lived, and economic conflict between slaves and poor white laborers. As Tomas Pollard has shown, the political events of the 1850s that culminated in war in 1861 are very much a presence in this novel (38-45). The text invokes the "severe Fugitive Slave Law" of 1850; "Its very injustice had created new sympathizers for fugitives, and opened new avenues of escape," facilitating Nancy's departure (222). In addition, Horace Greeley's abolitionist New York Tribune, which Mrs. Bywaters subscribes to and shares with her friend Rachel, is an important presence in the book. However, slavery is never openly debated in Sapphira; instead, it is a silencing, isolating force, muffling the rapport between Rachel and her father and preventing a loving understanding between Nancy and Till, to mention only two examples. When the novel was published, Cather wrote to her old (and Southern) friend Viola Roseboro' that she had wanted to explore something "Terrible" in her book, an estranging force beneath the surfaces (often pleasant) of domestic life. Sapphira makes it very clear that a rending conflict is coming and that the issue of slavery, grounded in race, will be at its center. The war is not "drained of evil"; instead, the "Terrible" presence of evils grounded in slavery blights, at least partially, almost every relationship in the book.

Cather's actual picture of the Civil War years is folded into the novel's epilogue. This picture does not emphasize local and family military heroes, such as the "Namesake" uncles. Nancy's nemesis, Martin Colbert, was a Confederate casualty. Rachel Blake reports of her cousin, "He'd got to be a captain in the cavalry, and the Colberts made a great to-do about him after he was dead, and put up a monument. But I reckon the neighbourhood was relieved" (290). Heroic trappings—rank and monument—do not obliterate Martin's local reputation as a lazy, predatory rake, and Martin is not mourned by his Southern neighbors.

The story of another Confederate casualty, a Back Creek Valley boy, emphasizes his pitiful suffering, not heroism: When Willie Gordon, a Rebel boy from Hayfield, was wounded in the Battle of Bull Run, it was [antislavery] Mr. Cartmell, Mrs. Bywaters's father, who went after him in his hay-wagon, got through the Federal lines, and brought him home. While the boy lay dying from gangrene in a shattered leg, . . . the Hayfield people, regardless of political differences, came in relays, night and day, and did the only thing that relieved his pain a little: they carried cold water from the springhouse and with a tin cup poured it steadily over his leg for hours at a time. (274) The character of Mr. Cartmell, who brings the wounded soldier home, is based on Cather's great-grandfather James Cather, and the story of his neighborly act of kindness was probably a family tale. In addition, some of Frederick County's local Civil War historians believe that Willie Gordon was probably based on the Boak family war casualty, James William ("Willie") Boak. The name "Willie," with its strong personal and family ties, would have been a significant choice for Cather, and possibly a private signal of kinship to this character, who died a few days after Second Manassas, as her uncle had. In One of Ours, Mahailey (whose prototype was Marjorie Anderson) tells a similar story of one her Confederate brothers, whom she says her mother brought home from Bull Run in a wagon to die "by inches" of gangrene in just the same way (1107-08). Cather seldom repeated incidents so closely in her fiction; the two publications of this sad little tale of a Civil War casualty suggest that it had made a powerful impression on her, perhaps because she heard it frequently as a child.

Sapphira's one gesture toward full-scale glorification of (Confederate)

war heroism also occurs in the epilogue. It is the account of "young Turner Ashby

of [neighboring]

Fauquier County, who held the Confederate line from Berkeley Springs to Harpers Ferry,—so

near home that word of his brilliant cavalry exploits came out to Back Creek with

the stage-driver" (275). Brigadier General Ashby was admired, Cather writes, by both

Union and Confederate supporters, and he became Frederick County's most-venerated

war hero; the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy is named for

him. Addressing her 1940 readers, Cather adds that Ashby died leading a "victorious

charge," on June 6, 1862, and that "Even today, if you should be motoring through

Winchester on the sixth of June, and should stop to see the Confederate cemetery,

you would probably find fresh flowers on Ashby's grave [an elaborate monument erected

by 'The ladies of Winchester' in 1881]. He was all that the old-time Virginians admired:

Like Paris handsome and like Hector brave. And he died young. 'Shortlived and glorious,' the old Virginians used to say" (275).

In this passage, Cather subtly acknowledges her close knowledge of Frederick County's

Civil War mythology. In Winchester, Confederate Memorial Day is celebrated on the

anniversary of Turner Ashby's death—to this day, Ashby's grave is indeed decorated

with flowers on this date, and all the cemetery's surrounding graves, including the

nearby grave of J.W. Boak, are marked with Confederate flags (see fig. 3). Addressing

her present-day (1940) readers who may be indulging in the new pastime of Civil War

automobile tourism, Cather repeats the florid language that glorified Ashby's war

exploits, but she discreetly distances herself from that language, attributing it

to "the old-time Virginians." She acknowledges Americans' continued interest in the

mythology of Civil War heroism (as had recently been amply demonstrated by public

enthusiasm for the book and film version of Gone with the Wind), and, in the mode of much post-Reconstruction Civil War fiction, she makes  Fig. 3. This photograph was taken in Stonewall Confederate Cemetery, Winchester, Virginia,

on June 7, 2001, the day after the observance of Confederate Memorial Day, which is

celebrated in Winchester on June 6, the anniversary of General Turner Ashby's death

in battle in 1862. As Cather mentions in the epilogue to Sapphira and the Slave Girl,

Ashby's large tomb (inscribed THE BROTHERS ASHBY) is decorated with flowers, and all

the graves in the cemetery are decorated with small Confederate flags. One of the

small adjacent tombstones marks the grave of Willa Cather's uncle, James William Boak.

Photograph by the author. no mention of the issues for which the war was fought, emphasizing personal heroic

style instead.

Fig. 3. This photograph was taken in Stonewall Confederate Cemetery, Winchester, Virginia,

on June 7, 2001, the day after the observance of Confederate Memorial Day, which is

celebrated in Winchester on June 6, the anniversary of General Turner Ashby's death

in battle in 1862. As Cather mentions in the epilogue to Sapphira and the Slave Girl,

Ashby's large tomb (inscribed THE BROTHERS ASHBY) is decorated with flowers, and all

the graves in the cemetery are decorated with small Confederate flags. One of the

small adjacent tombstones marks the grave of Willa Cather's uncle, James William Boak.

Photograph by the author. no mention of the issues for which the war was fought, emphasizing personal heroic

style instead.

Female heroism, however, is more explicitly celebrated—or at least noted—in the novel. What we know of the Virginia stories of the war years that were told in the Cather/Boak family suggests that they provided some precedents and models for daring female behavior. Carrie Miner Sherwood's memories of Grandmother Boak's tales to her grandchildren emphasize Rachel Boak's audacious nighttime forays into the camps of both armies to nurture hungry soldiers. And Sidney Cather Gore kept voluminous journals during the war years that chronicle her tireless efforts to provide food, spiritual guidance, and medical care for both Union and Confederate troops, at her home and at the hospitals in Winchester and nearby, as well as her anguished efforts to reconcile her Union political principles with her warm sympathy for the suffering of Confederate neighbors. In 1923 Sidney Gore's youngest son, James Howard Gore, edited and published his mother's journals, and since Cather regularly visited and corresponded with this cousin, it seems likely that she would have read his edition of Sidney Gore's journals, as well as hearing stories from her aunt (with whom she stayed on her first return visit to Virginia in 1896). In Sapphira, both Rachel Boak and Sidney Gore, as Rachel Blake and Mrs. Bywaters, act on their antislavery principles in ways that are audacious and dangerous, as Rachel engineers her mother's slave's escape from slavery and Mrs. Bywaters openly subscribes to an abolitionist newspaper and then hides fugitive Confederate soldiers in her house. They are models of active heroism that is not "drained of ideology." And, as I'll argue later in this essay, there are heroic elements in Nancy's story as well: her return was a "thrilling" story of personal achievement that Cather remembered throughout her life. These women characters in Sapphira offer alternative conceptions of what a "war hero" might be. Beyond the generic monument and "great to-do" that memorialized Martin Colbert, they suggest a heroism of principled activism that addresses the core issues of the Civil War instead of ignoring them.

The writing of Sapphira had a double purpose for Cather. First, it allowed her to plumb the Terrible as it was grounded in her own family's Virginia history and in the domestic and local life that she experienced at Willow Shade in her own early years. Thus, as I've said, the book does confront, in many ways, the central issues for which the war was fought, particularly slavery. In fact, as several critics have observed, Sapphira is the most politically confrontational of Cather's novels. But Cather also wrote this novel for solace and escape. The late 1930s were the worst period of her life, she told friends. Her favorite brother, Douglass, died in June 1938—her first loss of a sibling. A few months later, the great romance of her life, Isabelle McClung Hambourg, also died. In addition, Cather was distraught over the news of the developing war in Europe, where she had many friends.Work on Sapphira was a solace, she said, and she wrote much more material than she could use, simply for the relief of writing about her nineteenth-century Virginia home. Thus Sapphira is, in many ways, a novel of war and loss written to escape war and loss.

This is evident in the sometimes contradictory picture of war and Reconstruction that emerges from the epilogue. Cather acknowledges little antagonism among Frederick Countians: "The war made few enmities in the country neighbourhoods," she writes (274), an assertion that seems at least partially to contradict her own family history. The pervasive postwar "shame of defeat" and "profound hopelessness" described by a later historian, Wyatt-Brown, are absent from Cather's account of the returning Frederick County "Rebel" soldiers; they "were tired, discouraged, but not humiliated or embittered by failure. The country people accepted the defeat of the Confederacy with dignity, as they accepted death when it came to their families. Defeat was not new to these men"—they were farmers, and accustomed to crop failures (276). The "lost cause" is subsumed in the ongoing (and perhaps comforting) rhythms of nature and agriculture. In the novel, unlike Southern mythology of Reconstruction horrors, there are almost no appearances by carpetbaggers, scalawags, or other demonized figures—"Mrs. Bywaters was still the postmistress. She had not been removed in the 'carpetbag' period, when so many questionable Government appointments were made" (274). The postwar changes seem mostly positive, and Old South traditions don't appear to hamper young adults of Cather's parents' generation: "This new generation was gayer and more carefree than their forebears, perhaps because they had fewer traditions to live up to" (277).One of those abandoned traditions would have been slavery, of course; anxiety about slaveholding was a major reason why Rachel Blake and Henry Colbert ("forebears" of Cather's mother) were seldom gay and carefree before the war.

The centerpiece of the epilogue, of course, is "Nancy's Return," seen through the eyes of Cather as a child of five. Nancy left Frederick County in secret defiance of Virginia and U.S. law, as an abused and terrified slave girl. Cather's text suggests an almost causal relation between Nancy's escape and the Civil War, "which came on so soon after Nancy ran away" (273). Nancy returns, around 1881, as a self-possessed, prosperous Canadian woman, a legendary hero in young Cather's household. "Well, Nancy child, you've made us right proud of you," Cather's grandmother Rachel says (283). Openly visiting her mother, Till, and the descendants of her former owner, Nancy is evidence of all that the Civil War has made possible. In fact, she is a triumph of personal reconstruction. Having remade herself as a Northern woman with fashionable clothes, British-accented speech, a secure job, and a mixed-race marriage and family, she can now return to claim the best resources of her Southern childhood. For young Cather, Nancy is an important first acquaintance with a successful urban woman who can move from region to region and still retain her selfhood. Indeed, Nancy may be seen in this autobiographical narrative as one of young Cather's first models for her own peripatetic, multi-regional life in the post-Reconstruction United States. Yet, at the same time, little Willa betrays the marks of her postbellum conditioning as an heir of the Confederacy: she is suspicious of Nancy's precise Northern speech and prefers the "shade of deference" in Nancy's voice "when she addressed my mother"—the granddaughter of Nancy's owner (284). The child entirely approves of her family's hospitality to Nancy and Till: after the white Cathers have eaten, the black visitors are served at a segregated second table. Intentionally or not, Cather's picture of "Nancy's Return" shows us both the changed possibilities that had opened up for African Americans after the war and the constraints that still existed, especially in the South—and that were taking legal shape in Jim Crow laws.

The epilogue's picture of other African Americans after the war contrasts even more vividly with the rather calm and placid view of the Reconstruction years that Cather constructs. Some work for the families that formerly owned them; Cather's father employs some of Sapphira's former slaves. One mill worker, Sampson ("Master's steadiest man" [288]), has made a successful life for himself and his family in Pennsylvania, but he is homesick for the grist mill where he was a slave and for Virginia cooking. He tells Till, "I ain't had no real bread since I went away." Where he works, "the machines runs so fast an' gits so hot, an' burns all the taste out-a the flour" (289). Sampson's story suggests that even the ablest of former slaves may be displaced and unhappy outside the Old South, where they must contend with the facts of industrialization.

Even worse is the tale of another freed slave, "Tap, the jolly mill boy . . . whom everybody liked." People said he hadn't been able to stand his freedom. He went to town . . . and picked up various jobs. . . . Early in the Reconstruction time a low German from Pennsylvania opened a saloon and pool hall in Winchester, a dive where negroes were allowed to play, and gambling went on. One night after Tap had been drinking too much, he struck another darky on the head with a billiard cue and killed him. (290) Tap was hanged for this crime, despite local white farmers' testimony to his "good character." "Mrs. Blake and Till always said it was a Yankee jury that hanged him; a Southern jury would have known there was no real bad in Tap" (290).

The implications of this story, corroborated by the two old women, white and black, who were young Cather's major early teachers, are the most appalling of Southern Reconstruction-era dogma: a "low" outsider—a carpetbagger Northerner and immigrant— has created a dangerous public space where the races mix, and when Tap impulsively kills "another darky" there, "no real bad" has been done, according to the native white men of the neighborhood. Tap's story expresses the postwar Southern ideology summarized by Eric J. Sundquist: "Emancipation, it was argued, had ushered in an age of childlike loss of direction, mental and physical decline, and a propensity for violence on the part of blacks" (336).

The most complex portrayal of an African American in Cather's epilogue is Till. Matilda Jefferson, the prototype for Till, had been a slave in the household of Jacob and Ruhamah Seibert and remained there, after emancipation, until Ruhamah's death in 1873. Thereafter, from the evidence of Cather's letters and the epilogue, she lived on in the cabin that had been her slave dwelling and often visited or worked in Cather's parents' household. In the 1856 portion of Sapphira, Till is Sapphira's housekeeper and personal slave. She is an austere and taciturn figure who appears estranged from the slave community. Her strongest attachments are to white women: the English housekeeper who trained her and her mistress, Sapphira. She never tells stories, not even to her daughter, Nancy.

But the Till of the epilogue is in many ways transformed into a typical figure from postbellum literature. As an erect, "spare, neat little old darky" (280), Till is a physical refusal of the buxom, maternal "mammy" stereotype so popular in postwar fictions of the Old South. But in other ways, she replicates that type: as a lovingly remembered member of Cather's Virginia household, she is a benign presence, tenderly solicitous of the white child's every desire—such as little Willa's wish to witness the reunion of Nancy and Till—even when it inconveniences herself and her own child, Nancy.

Such solicitude is tellingly reminiscent of one of the best-known post-Reconstruction Southern storytellers, Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus. Blight says that Harris's first Uncle Remus book, Uncle Remus: His Songs and Sayings (the best-selling American book of 1880), "may have set the literary tone for the reconciliationist eighties" (228). Cather's family apparently shared in the national enthusiasm for Uncle Remus; in "Old Mrs. Harris," Mr. Templeton, a character based on Cather's father, tells an Uncle Remus tale to his receptive children. Uncle Remus's rapt and indulged listener is, like the young Willa of the epilogue, a white child, the descendant of Remus's former owners. Remus also puts himself at the child's disposal, and, just as Till invokes her mistress "Miss Sapphy," Remus's ultimate authority is the antebellum "ole Miss." The little boy's family encourages his visits to Uncle Remus's cabin; Willa's parents leave her at Till's former slave cabin to "hear the old stories." According to Robert Hemenway, "The Uncle Remus stories create a racial utopia. . . . Uncle Remus's cabin constitutes one of the most secure and serene environments in American literature, . . . and Uncle Remus reassured Southern whites . . . [that]free black people would love, not demand retribution" (19-20). Till's cabin is a similarly protected space, and Till's stories about her master and mistress are full of lovingly remembered detail and respect for her owners; she never speaks a word to young Willa that might be interpreted as criticism of the institution of slavery as she experienced it.

Cather makes Till's evaluation of Sapphira the ending of her epilogue. Till recounts Sapphira's brave, solitary death from heart disease, in her parlor, as a triumph of whiteness and of class: the "fine folks" of Sapphira's privileged girlhood on a Loudoun County plantation came for her, "and she went away with them" (294). Till concludes that Sapphira should have never left her original antebellum home for the more volatile border territory of Frederick County, where there was no settled social and economic hierarchy and "nobody was anybody much" (295). In other words, Till defends (at least for her mistress) the seemingly fixed world of a prosperous antebellum plantation, a world that is (unlike the 1856 Back Creek of the novel's major action) untouched by the tensions that will erupt in the Civil War.

According to Blight, in the Uncle Remus stories, "Harris's achievement was to create a world where on the one hand the Civil War never really needed to have happened, but on the other, all the deception, cunning, and bare-bones competition the underdogs of life could muster was necessary for their very survival" (228-29). In Uncle Remus's tales, of course, the wily trickster Brer Rabbit epitomizes the survival strategies employed by economic "underdogs," particularly slaves. In Sapphira, Till's stories to little Willa also evoke an antebellum world where therewas no necessity for a Civil War, and Till conspires with Willa's grandmother to ensure that the child remains ignorant of "deception, cunning" and desperate survival strategies. For example, when the name of Martin Colbert comes up in the child's hearing, Rachel Blake gives Nancy and Till a glance "that meant it was a forbidden subject" (290), and the little girl hears nothing of Sapphira's animosity to her slave girl, Martin's relentless pursuit, and Nancy's desperate strategies to evade him. The doubleness of the Uncle Remus stories, Blight says, epitomizes the reconciliationist agenda of the 1880s. Perhaps it is not surprising that Sapphira shows a similar duplicity, since it is grounded in the stories Cather first heard in Reconstruction Virginia.

Of those stories, Cather says in her epilogue, "I soon learned that it was best never to interrupt with questions,—it seemed to break the spell. Nancy [during her visit] wanted to know what had happened during the war, and what had become of everybody,—and so did I" (288). Sapphira does not fully tell us the story of "what happened during the war" in Cather's ancestral Virginia. But it does give us a powerful sense of why the war happened and of "what had become of everybody"—how lives of white and black Virginians were forever changed. To piece together that story from the censored memories of white and black elders, like Till and Rachel Blake, demanded intense and strategic listening on the part of young Cather (as well as the research and reflection of the mature novelist). Till's stories also required close attention to nuances of tone and to "hints that she dropped unconsciously" (292). Looking and listening to all that was said and not said, the child must have received her first lessons in the telling of stories about the Civil War and the years before and after and all of the rigors and restrictions that accompanied such stories.

Cather was sixty-seven—the approximate age of her Grandmother Boak and "Aunt Till" in the epilogue—when Sapphira was published. Clearly, the popular priorities of youthful male heroism and nationalist art that she had explored in the two versions of "The Namesake," her first efforts to write out of her own Civil War history, no longer engaged her. But the priorities of "race and blood and kindred" still did. In her last novel she takes her place among the family women, telling the stories of the "what had happened during the war, and what had become of everybody."[7] And, although Till appears to have the (evasive) last word, in the novel's famous final note, printed on the last page after "the end", and signed by the present-day novelist, WILLA CATHER, (in capitals slightly larger than "the end"), Cather foregrounds her own memories, through her use of "Frederick County surnames," which she heard from her parents in early childhood. "The names of those unknown persons sometimes had a lively fascination for me," she says (295)—and some of them have been incorporated into the novel. I read this idiosyncratic note as Cather's reminder to us that this is her material, and she is the surviving storyteller now. Sapphira and the Slave Girl is, among many other things, Cather's Civil War story. In it, she acknowledges her personal history and that of her community and nation and reminds us of how difficult and freighted a process the telling of Civil War stories (still) is.

NOTES

Cather's account of Lyon Hartwell's career bears a resemblance to the career of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), arguably the best American sculptor of his time, who, in the Shaw Memorial installed on Boston Common in 1897, created the best-known and most admired work of Civil War memorial sculpture. An American citizen, Saint-Gaudens was the son of immigrant parents and studied in both Rome and Paris; like Lyon Hartwell, he lived in Paris for a portion of his career, which was launched by a much-praised memorial to Union admiral David Farragut in Madison Square Garden. The Shaw Memorial commemorated a Union officer and the African American regiment he led; it had special significance for Saint-Gaudens, who worked on it for more than twenty years. When the memorial was at last unveiled, in an elaborate and widely publicized ceremony that included important speeches by William James and Booker T.Washington, the Boston Transcript hailed it (as Blight has noted) as bringing "new artistic fervor to Civil War memorialization" (Blight 338-443; The Shaw Memorial 20-23, passim).

As a professional journalist and a voracious reader, Cather would undoubtedly have been aware of the Shaw Memorial's unveiling. In her first year as an editor of McClure's (1906-07), Cather lived in Boston, not far from the Boston Common, where the Shaw Memorial was installed, and almost certainly saw it there. This was the year during which "The Namesake" was published and, presumably, written. It is also interesting to note that a selection of Saint-Gaudens' letters was published in McClure's in 1908, the year after his death. So there are many reasons to presume that Willa Cather knew of this notable sculptor's career as a creator of Civil War memorials and might have it in mind as one of her sources for the figure of Lyon Hartwell.

(Go back.)