From Cather Studies Volume 8

Edith Lewis as Editor, Every Week Magazine, and the Contexts of Cather's Fiction

On 26 August 1915 the New York Times reported the spectacle of two “Women Editors” who became “Lost in Colorado Cañon”

as a “Result of Trip with Inexperienced Guide.” “Miss Willa Sibert Cather, a former

editor of McClure’s Magazine, and Miss Edith Lewis, assistant editor at Every Week,

had a nerve-racking experience in the Mesa Verde wilds,” they reported, giving Lewis

and Cather roughly equivalent status as magazine professionals and comic fodder (“Lost”).

The war in Europe was still far away for most Americans that August, although the

sinking of the Lusitania in May had inched the conflict closer. In July, Cather had been scheduled to travel

to Europe with S. S. McClure to interview European leaders about the war; however,

nearing the end of her long and gradual turn away from magazine editing and journalistic

writing to full-time fiction writing, she regretfully surrendered the financial rewards

and prospects of adventure the European trip presented (Woodress 262). Although her

fiction continued to appear in magazines and she wrote occasional cultural commentary,

the canceling of the European trip with McClure marked a definitive shift in Cather’s

career—with the exception of one article in the

Fig. 1. Edith Lewis’s passport photograph, 1920. Courtesy of the National Archives

and Records Administration.Edith Lewis’s passport photograph, 1920.

Red Cross Magazine in 1919, Cather engaged the war as subject matter only in fiction.

Fig. 1. Edith Lewis’s passport photograph, 1920. Courtesy of the National Archives

and Records Administration.Edith Lewis’s passport photograph, 1920.

Red Cross Magazine in 1919, Cather engaged the war as subject matter only in fiction.

In 1915, however, when the Times could collectively label Cather and Lewis “women editors,” Lewis was just beginning a three-year stint as an editor at a new magazine, the circulation of which would eventually exceed half a million. As Cather was making the transition from magazine work to full-time fiction writing, Lewis’s editorship would keep magazine work a part of Cather’s wartime home front at their shared Greenwich Village apartment, Cather’s “scene of writing.”[1] Although Lewis has figured in Cather scholarship as the silent hostess looking after Cather’s guests at the Friday-afternoon teas at Bank Street, she was also looking after her own guests, Every Week staffers, and bringing the world of the magazine office into the domestic space and social milieu she shared with Cather. Every Week thus became one of the frames through which Cather contemplated the events in Europe and is, as this essay argues, an important context for reading the two novels that grew out of Cather’s experiences from 1915 to 1918,My Ántonia and One of Ours.

Lewis’s work at Every Week is also crucial to recovering and fully understanding her direct involvement in Cather’s creative process as Cather’s editor. Lewis brought her magazine colleagues home to tea at Bank Street, but she brought something else: editorial skills acquired through years of professional experience. The nature and scope of magazine editorial work is not easy to recover, because such work is collaborative and meant to be invisible—an identified editor in chief and the collective editorial “we” represent an entire office full of people working together.[2] Furthermore, complete office archives of magazines are seldom preserved and made accessible to scholars (there is no such archive for Every Week, nor for McClure’s). Nevertheless, putting together the extant scattered pieces and reading against the collective anonymity of the magazine editorial enterprise, this essay makes Edith Lewis’s editorial work visible and locates the origin of her role in Cather’s creative process.

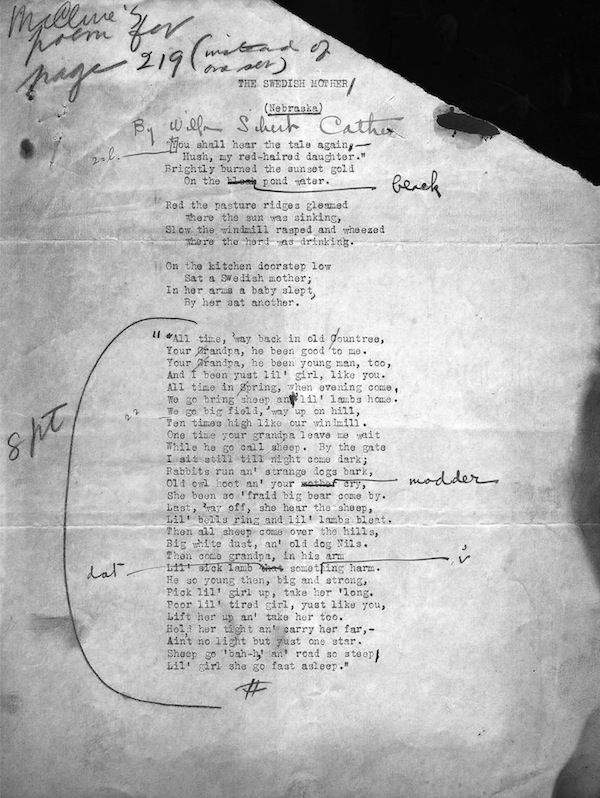

EDITH LEWIS AT EVERY WEEK

After graduating from Smith College in Massachusetts in 1902, at the age of twenty, Edith Lewis returned to her hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska, for a year to teach school (Homestead and Kaufman 61). However, in 1903, shortly after meeting Cather in Lincoln, she left for New York, where she worked as a copy editor at the Century Publishing Company (“Alumnae”). In 1906, Lewis followed Cather to McClure’s for a position as an editorial proofreader (Lewis, Willa Cather Living xvii); she did not rest long on the lower rung of the magazine’s professional ladder. As she wrote on her job application to the J. Walter Thompson Co. advertising agency in November 1918, she “was successively proofreader, make-up editor, art-editor, literary editor & acting managing editor” at McClure’s (Personnel File). Cather effectively ended her editorial work at McClure’s by the fall of 1911, when she went on leave—resigning in 1912 without returning to her duties. However, she continued to contribute freelance to McClure’s through 1915 and beyond. No manuscripts or typescripts of Cather’s fiction published before 1925 are known, but red-pen revisions in Lewis’s hand appear on the typescript of Cather’s poem “The Swedish Mother” from which copy was set for publication in McClure’s in November 1911 (figs. 2 and 3). If typescripts of Cather’s other McClure’s contributions from 1911 through 1914 (such as Alexander’s Bridge or “Three American Signers”) survived, they would almost certainly show evidence of Lewis’s red pen in her capacity as a McClure’s editor.

Lewis resigned from McClure’s in early 1915 because of “fundamental changes (for the worse) in the policy & organization”

(Personnel File) and accepted a position as assistant editor of the Associated Sunday

Magazines, a Sunday newspaper supplement just launching a Monday newsstand version,

Every Week.[3] Under the leadership of editor-in-chief Bruce Barton, an ambitious young Amherst

College graduate, Every Week as a three-cent

Fig. 2. The typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem “The Swedish Mother,” copyedited by Edith Lewis.

Courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington INThe typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem “The Swedish Mother”

Fig. 2. The typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem “The Swedish Mother,” copyedited by Edith Lewis.

Courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington INThe typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem “The Swedish Mother”

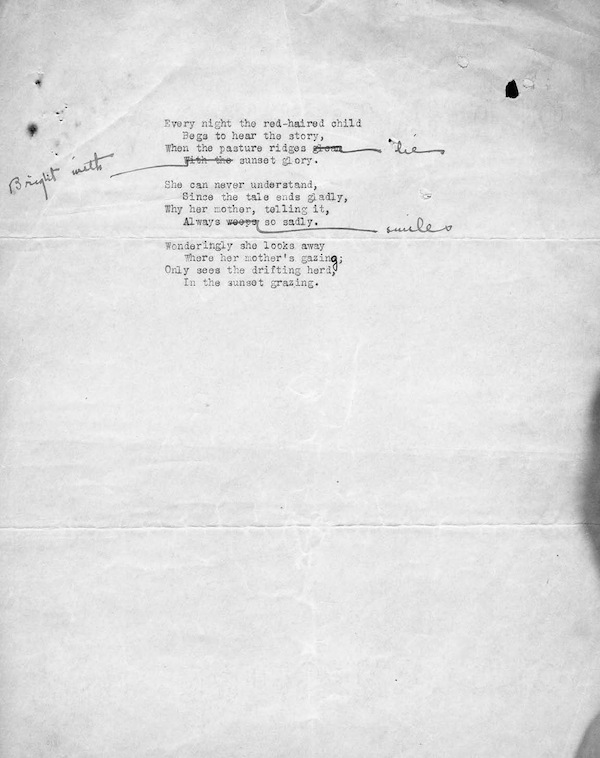

Fig. 3. The typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem, “The Swedish Mother,” second page. Courtesy of the

Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington INThe typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem, “The Swedish Mother,” second page.

weekly rapidly achieved a high circulation. From its 3 May 1915 launch to its demise

on 22 June 1918 its circulation grew to over six hundred thousand. Published in a

large format with colorful pictures of pretty girls by top illustrators on its front

cover, Every Week featured an evolving mix of fiction, advice, commentary, news items, and photographs

with a human-interest focus. Barton’s provocative editorials, which promoted Christian

morals, capitalism, and individual self-improvement, became a prominent feature of

each issue. Burton Hendrick, whom both Cather and Lewis knew from his years as one

of McClure’s primary investigative writers, contributed regular feature articles to Every Week on politics, world affairs, economics, and business. Notably, Cather herself contributed

a nonfiction article to Every Week that appeared in August 1915, continuing the pattern earlier established at McClure’s of Cather as contributor and Lewis as editor. In “Wireless Boys Who Went Down with

Their Ships” (2 August 1915), Cather recounts the heroic deaths of twelve young American

wireless operators who, as civilian merchant seaman, stayed at their posts on sinking

ships, sending out messages to enable the rescue of others (including passengers)

rather than abandoning ship to save themselves. Although Cather does not mention the

war in Europe in this article, with the recent memory of the sinking of the Lusitania, the bravery of these civilian “radio boys” would certainly have called up the looming

war threat.

Fig. 3. The typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem, “The Swedish Mother,” second page. Courtesy of the

Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington INThe typescript setting copy for McClure’s magazine of Willa Cather’s poem, “The Swedish Mother,” second page.

weekly rapidly achieved a high circulation. From its 3 May 1915 launch to its demise

on 22 June 1918 its circulation grew to over six hundred thousand. Published in a

large format with colorful pictures of pretty girls by top illustrators on its front

cover, Every Week featured an evolving mix of fiction, advice, commentary, news items, and photographs

with a human-interest focus. Barton’s provocative editorials, which promoted Christian

morals, capitalism, and individual self-improvement, became a prominent feature of

each issue. Burton Hendrick, whom both Cather and Lewis knew from his years as one

of McClure’s primary investigative writers, contributed regular feature articles to Every Week on politics, world affairs, economics, and business. Notably, Cather herself contributed

a nonfiction article to Every Week that appeared in August 1915, continuing the pattern earlier established at McClure’s of Cather as contributor and Lewis as editor. In “Wireless Boys Who Went Down with

Their Ships” (2 August 1915), Cather recounts the heroic deaths of twelve young American

wireless operators who, as civilian merchant seaman, stayed at their posts on sinking

ships, sending out messages to enable the rescue of others (including passengers)

rather than abandoning ship to save themselves. Although Cather does not mention the

war in Europe in this article, with the recent memory of the sinking of the Lusitania, the bravery of these civilian “radio boys” would certainly have called up the looming

war threat.

Fiction featured prominently in Every Week, with lavishly illustrated serial novels and short stories occupying a third of each issue. While most fiction leaned heavily toward popular genres— Western, mystery, romance—and most of the contributors have been forgotten by literary history, Every Week also published some fiction writers with names more familiar to literary historians, such as Susan Glaspell, Conrad Richter, Sinclair Lewis, Edna Ferber, Mary Wilkins Freeman, and Zona Gale. At Every Week, Edith Lewis continued to practice the editorial craft she had developed at McClure’s, having primary responsibility for selecting and editing the fiction, much of which she bought from agent Paul Revere Reynolds, who became Cather’s agent in 1916.[4] When called as a reference for Lewis’s job application to Thompson, George Buckley, president of the Crowell Publishing Company (which purchased Every Week in 1916), said Lewis “had a very fine mind, really a brilliant mind: that she was one of the best judges of fiction they had ever known; that she had rewritten a great deal of the stuff that had come in to them” (Personnel File).

Lewis’s tact and sensitivity with authors comes through in correspondence between Every Week and Conrad Richter, then a struggling author early in his career. Soon after the magazine’s launch, when one of his stories had been selected as the best short story of 1914, Barton wrote him, asking him to submit a story for consideration (Johnson 62). Barton expressed admiration for the story Richter submitted, “The Laugh of Leen,” but said that because the magazine published relatively few short stories in each issue, “we ought to have as much action as possible” (Barton to Richter, 26 May 1915). Reynolds suggested that Richter “give [him] a chance at something else,” and Lewis was left with the chore of rejecting the second story he submitted. “Mr. Barton and I have both been interested in this story,” she wrote, “but it seems to us a little too quiet and leisurely in tone to be just the sort of thing we are looking for.” Two years later, with the Paget Literary Agency trying to place his stories, Richter’s agent reported a conversation with “one of the editors of Every Week, who had read” yet another Richter story then in unsuccessful circulation. This unnamed editor (almost certainly Lewis) advised that half of the editorial staff “wanted to accept it [but] ultimately decid[ed] against it, because . . . the opinion in [the] office was that your writing and handling of material was not as good as the ideas in your stories warranted. This editor seemed to think that your work was inclined to be long winded and too indirect, in treatment, always taking, so to speak, a long round about way, instead of a straight direct path to the incident” (17 May 1917). When Paget finally placed a Richter story with Every Week (Paget to Richter, 17 October 1917), it was “The Pippin of Pike County,” a briskly paced western tale set in a Montana silver-mining town (16 March 1918). When Richter responded to Bruce Barton’s letter announcing the magazine’s imminent demise (Richter to Barton, 24 May 1918), he asked Barton to “Please remind Miss Lewis of my appreciation of her kind interest in my humble scratchings.”

Lewis also played a central role in the production of the third of each issue of Every Week devoted to captioned photographs and very brief articles. In her Thompson application she enumerates the writing of “captions, editorial notes & announcements, & short articles” as part of her duties at Every Week. She also claimed responsibility for “the organization of [the] gravure [picture] pages and The Melting Pot, two of the most successful departments of the magazine” (Personnel File). As Barton recalled, “We had to close so far in advance of publication that it would be impossible for us to use current news pictures. So I invented the picture-caption article in the form of double spread (center) of pictures and long, factual, informative, and (often) amusing captions. Miss Edith Lewis, who lived with Willa Cather . . . was my assistant. My other assistants were youngsters, some of whom became very successful later. The picture caption feature was a big success; as well as the great variety of short material” (Barton to Brower). While claiming to have “invented” the format, Barton also described the picture-caption section as “a joint-production—three or four of my bright young people wrote them, and Miss Edith Lewis, my Managing Editor, edited them, and then I finally ran them through my typewriter” (Barton to Balch). The text of “The Melting Pot,” like the photo captions, appeared anonymously. A two-page illustrated feature that digested and excerpted content from current books and periodicals, “The Melting Pot” featured much of the “short material” to which Barton attributed the magazine’s popularity.

Despite Barton’s role as the spokesman of mainstream American values and as the public face of Every Week, the “youngsters” who toiled anonymously to produce these pages of photographs and brief articles were an interconnected and ever-changing cast of bohemians in their twenties. One of these, Anne Herendeen, fondly recalled the conventional Barton’s attitude toward the unconventional female members of his staff: “I remember what you [Barton] said about ‘those short-haired girls’ on your Every Week staff. You said ‘But they’re smart’” (Herendeen to Barton, 14 October 1959). Herendeen cheerfully characterized two of the young men on the predominantly female staff, John Colton and John Chapin Mosher, as “delightful deviants, god bless them” (Herendeen to Barton, 5 May 1960). While his bohemian junior staff regarded Barton with a mixture of bemused affection and self-righteous scorn, they clearly respected and loved Lewis, their quieter managing editor. Barton joked with the staff and dreamed up ideas for promoting the magazine, but Lewis was, as staff member Brenda Ueland recalled, “our real boss on Every Week” (Me 156).

Although Lewis began as assistant editor, her role as the hands-on editor and manager of the magazine’s daily operations was clear from the start, and she soon officially acquired the title of managing editor (“Lincoln Girls”). In letters to her mother, Lella Faye Secor simply identified Lewis as “the editor,” the person who judged her freelance submissions and decided whether she would be asked to do more work (Florence 41–51), and she called Barton the “chief mogul” (51). Secor at first found Lewis to be “one of those stoical sort of women who let you know very little of what she really thinks” (41), but later, when she joined the magazine’s staff, she relished Lewis’s praise of her work. Early in Ueland’s time at the magazine, she wrote her mother that she and “Miss Lewis . . . have a secret liking of each other. She is pretty and shy and we both have the same trouble of jerky talking. I have been working in the same room with her for the past month, and strange to say (for me), I love her” (qtd. in Me 160). In her memoir, Ueland praises Lewis as “the best boss I ever had, the most intelligent, the most just, the kindest and the bluntest. Her warm hazel eyes looked at you and she would say right out: ‘These captions are no good; they are all over the place!’ and at the same time, because of bashfulness, she would be almost lisping and blushing deeply. From anybody else, it would be an unbearable wound (unfeeling, mean editors weazen all one’s ability, just as mean employers do) but not from her. And I respected her so much. Yes, it was true, I saw at once: the captions were frightful. I went and did them again. I was grateful for all her guidance” (158–59).

EVER WEEK, THE WAR, AND ONE OF OURS

When Every Week launched in 1915, the war was a regular, although minor, presence in the magazine, as it was in the lives of most Americans. Through 1915 the war remained largely somebody else’s problem, a subject for detached contemplation, speculation, and analysis, much of that analysis carried out in regular contributions by Burton Hendrick. For instance, he devoted articles to explaining how European nations were financing their war efforts by printing new money (20 September 1915) and to speculating on “How Long England [Could] Hold Out” financially (6 December 1915)—his answer was indefinitely. But in 1916, commentary on the war in Every Week began taking a more anxious and introspective turn, as U.S. National Guard troops were called up for the so-called Punitive Expedition into Mexico, led by Cather’s old friend from her school days in Lincoln, General John J. Pershing. On 6 August 1916, Barton (who had been advocating military preparedness in previous editorials) devoted his editorial “On Seeing My Brother Ride Away to Mexico” to a tirade against the long-standing American policy of not preparing for war, of marching troops off to Mexico without uniforms, typhoid inoculation, or modern weapons. The Mexican action also personally affected Every Week when staff member John Colton’s National Guard cavalry regiment, Squadron A, was called up and spent nine months on the border under the command of Pershing (“Author of ‘Rain’”). And, as Lewis would have been well aware, Cather’s cousin G. P. Cather, the prototype for Claude Wheeler in One of Ours, was serving on the Mexican border under Pershing (Harris 636).

In late 1916, the war “over there” in Europe became increasingly prominent inEvery Week, with the magazine actively seeking contributions from those who had seen the conditions in Europe firsthand. For instance, Lewis tried to enlist her and Cather’s former boss S. S. McClure as a contributor because of his war-related editorials in the Evening Mail. “Mr. Barton wants me to see you about doing an article for us,” she wrote in November 1916. “We wish very much that we could have you do something for Every Week. I have been following your editorials with the greatest interest. I hear a great many people speak of them.” Based on McClure’s controversial 1916 trip to Europe, these articles became the basis of both a lecture tour and a book, Obstacles to Peace (1917).[5] Although Lewis’s attempt to recruit McClure as a contributor failed, Every Week succeeded in acquiring accounts from others who had recent experience of Europe. In December, journalist William Gunn Shepherd contributed an article on “The Bravest Man I Met in Five Armies,” and an editorial note boasted, “As the correspondent of the United Press, Mr. Shepherd has seen the Great War on every front except the Russian . . . we are going to have quite a number of articles from him—all bully” (3 December 1916). The next week, Barton contributed his own full-length article praising the nine thousand Americans who were part of the Canadian forces fighting in Belgium, including at Ypres.

Anticipating the language and images that would soon dominate American war propaganda (which echo in One of Ours), Barton praises these American volunteers as “Knights errant— Clean and fine and red-blooded,” and quotes one of them as telling him, “I got to reading in the papers about them Germans tearin’ up Belgium and smashin’ churches and beatin’ up women and raisin’ the devil generally, and darned if it didn’t get me sore” (11 December 1916). Other war-related items published before U.S. entry into the conflict also suggestively prefigure scenes and images in the Nebraska section of One of Ours, in which Claude and his family and neighbors contemplate events far away in Europe. For instance, in January 1917, Every Week published a reproduction of a painting by Ralph Coleman, captioned “Somewhere in France,” of a young French peasant woman sitting pensively in a church, her Bible in her lap, while soldiers march by. The anonymous extended caption (written by someone on the Every Week staff, perhaps Lewis) begins with an unattributed quote from Thomas Jefferson: “Every man has two countries—his own and France.” Reflecting on the burdens borne by French civilians in the war and on their continuing unity in purpose despite differences within the nation, the caption opines, “Napoleon and Joan of Arc are two of the three miracles of French history. The third is the temper with which the French people received this war, and drove back the German army from within eight miles of Paris in the battle of the Marne” (29 January 1917).

These items, dated before the U.S. involvement into the war, evidence the growing interest of Americans in the war in Europe, and when the United States finally entered the war in April 1917, the war virtually took over Every Week. Considering that war information was managed by the federal government and the circulation of dissenting opinion effectively suppressed through the Espionage Act of 1917 (Peterson and Fite 95), it should come as no surprise that the content of Every Week was consistently prowar and patriotic (even though some of its young staff members were engaged in pacifist agitation in their free time). With a few minor exceptions, all departments of the magazine supported the government’s war program, asking readers to save food, subscribe to the Liberty Loan, engage in war relief work through the Red Cross, and gladly surrender their young men to the armed services, writing them cheerful letters to maintain good morale. The young staff writers under Lewis’s supervision and Lewis herself were thus deeply immersed in war publications. Half of Barton’s editorials addressed war issues, and a significant portion of “The Melting Pot” was turned over to digests of war items from books and other magazines. Brief digests were not enough, and during the year it took to train, equip, and transport American troops to Europe, Every Week relied on men who had already fought for other nations to contribute longer original articles about the battlefields of Europe. In the summer of 1917, Every Week introduced Irishman Captain A. P. Corcoran as a regular contributor. A motorcycle “despatch” rider or “buzzer” in the British army from August 1914 to July 1915 (discharged as a result of injuries sustained in the collapse of a communications tunnel at the Battle of Somme), Corcoran became a source of authoritative information about “trench life” for Every Week readers, who were invited to suggest topics on which he should write (16 July 1917, 27 August 1917, 18 May 1918).

Because the war affected the lives of Every Week staff members as much as it did the magazine’s readers, Lewis was left juggling an ever-changing roster of junior staff members. Ueland recalled the effect the war had on John Mosher, who “made jokes and burst into his spasmodic, agonized laugh. ‘I have a friend,’ he said, ‘whose mother is very anxious for him to go to the Front, to see the stuff that is in him’” (Me 166–67). In November 1917, Mosher enlisted as a private in the Medical Corps at the U.S. Base Hospital in Albany. He sailed to Liverpool on 1 May 1918 and served until February 1919 at the U.S. Base Hospital at Portsmouth, England, where working on the shell shock ward kept him away from the front lines but gave him a front-row seat for observing the mental disintegration of those who had seen action (“John. C. Mosher”).[6] Ueland followed her husband, who had been transferred by his employer to the Philadelphia area to support war-related production, and Lewis, with her staff rapidly shrinking, strongly urged her to contribute news digest items as a freelancer (Me 174).

By the end of 1917, the war had completed its spread into every corner of the magazine, finally making its way into its fiction. Back from Mexico, John Colton contributed his first works of fiction to Every Week, including “Lusitania Night” (18 May 1918), a story set in Germany on 7 May 1915 and depicting the country celebrating the sinking of the Lusitania (poor eyesight kept him from enlisting or being drafted for European service [“Author of ‘Rain’”]). Because the popularity of the digests in “The Melting Pot,” the magazine added a two-page digest section devoted exclusively to the war and anchored by Captain Corcoran’s continuing original contributions. The magazine also commissioned original war-related artwork, both for its cover and as full-page inside images (like the Ralph Coleman image described above). And, anxious to prepare readers for the imminent entry of their sons, husbands, and brothers into battle, Every Week increased its effort to seek out accounts from those who had already seen action, publishing the letters home of a slain member of the Lafayette Escadrille of the French Air Service, American Kiffin Rockwell (3 December 1917), and an interview by new staff member Freda Kirchwey with Lieutenant Pat O’Brien (30 March 1918), an American who enlisted in the Canadian Royal Flying Corps early in the war and gained fame by escaping German custody after being captured behind enemy lines.

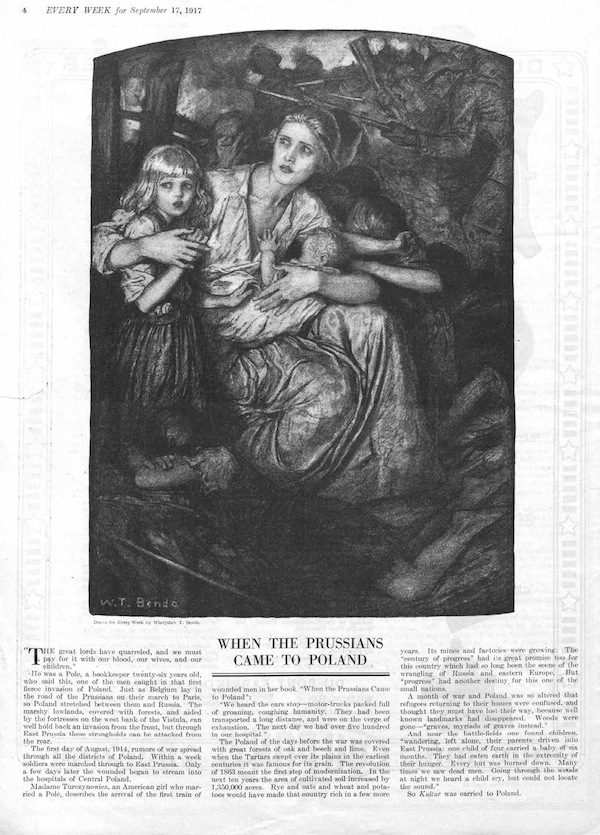

Richard Harris has recovered Cather’s extensive reading and research as preparation for writing One of Ours, but Every Week should also be included as a crucial resource for Cather as she re-created the war years from the perspective of Claude Wheeler. The magazine required Lewis to be unusually well versed in war books and periodical content, and that base of knowledge would have entered her everyday conversations with Cather. The magazine itself also doubtlessly crossed their threshold, being available for Cather to read during and after the war. It is striking how many works identified by scholars as Cather’s probable sources were excerpted or noted in Every Week.[7] For instance, the magazine published an article-length excerpt from Arthur Guy Empey’s memoir Over the Top (6 August 1917) and included in its war digest pages a snippet from Henri Barbusse’s novel Under Fire (16 March 1918). Other war items published in Every Week may represent previously unidentified Cather sources. The published letters of Lafayette Escadrille pilot Victor Chapman have been identified as contributing to Cather’s creation of fictional pilot Victor Morse (Harris 651–52), but Kiffin Rockwell’s letters and Kirchwey’s interview with Pat O’Brien may also have affected this composite character. Indeed, the photograph accompanying Rockwell’s letters in Every Week shows him in the company of Chapman, and one of his letters gives an account of the air battle that led to Chapman’s death. A. P. Corcoran’s reminiscences also find echoes in One of Ours. In “Women and Children behind the Fighting Lines” (9 February 1918), for instance, Corcoran recalls an incident strikingly similar to one in One of Ours. Claude comes upon a “pitiful group of humanity” consisting of a French woman with a sick baby in her lap and three older children, and one of the older children tells him that the baby “is a Boche.” Although Claude finds the child (implicitly a product of rape) repulsive, he carries it while his fellow soldiers carry the mother (473, 476–78). Similarly, Captain Corcoran reports entering a house in the French countryside in which terrified women and children cower, and later conversing with the group, he discovers that an infant had been fathered by a German soldier who occupied the house. Every Week illustrated this reminiscence with a picture of a soldier holding a baby (fig. 4).

As Lewis’s work life made its way into the Bank Street apartment, Every Week’s significance for Cather during the war years went beyond simple source hunting,

however. Ueland places herself, Herendeen, and Mosher at Cather and Lewis’s Fridayafternoon

teas in 1916 (Me 160), and as a good managing editor, Lewis certainly could not have excluded other

junior staff from the honor of afternoon tea in their “real boss’s” home. Ueland describes

herself and Mosher as “young and nobodies, listen[ing] in silence” as Cather debated

with music critics Louis

Fig. 4. A page of World War I material from Every Week magazine, 9 February 1918.A page of World War I material from Every Week magazine, 9 February 1918.

Sherwin and Pitts Sanborn. She describes Cather as “affirmative and masculinely intellectual”

and “her talk . . . very definite,” while “our darling, Miss Lewis, was always shy and quiet, gently blushing if you said something

that made her laugh, and she just quietly saw to it that we had a nice time and that

there was hot water for tea” (160).

Fig. 4. A page of World War I material from Every Week magazine, 9 February 1918.A page of World War I material from Every Week magazine, 9 February 1918.

Sherwin and Pitts Sanborn. She describes Cather as “affirmative and masculinely intellectual”

and “her talk . . . very definite,” while “our darling, Miss Lewis, was always shy and quiet, gently blushing if you said something

that made her laugh, and she just quietly saw to it that we had a nice time and that

there was hot water for tea” (160).

W.T. BENDA AND EVERY WEEK

The case of illustrator W. T. Benda’s work for Every Week also provides evidence of the mixing and merging of Lewis’s magazine work with Cather’s

work as a novelist. Benda’s Every Week work supports Janis Stout’s suggestion that My Ántonia, a novel depicting events in the late nineteenth century, bears marks of its composition

during World War I (155, 164–5). Although Benda’s illustrations appeared regularly

in McClure’s during Cather’s tenure as managing editor, Lewis continued her working relationship

with Benda into the war years, with his first illustration for Every Week being a headpiece for an essay by University of Nebraska sociologist George Elliott

Howard’s essay “Will Women Do the Marrying after the War?” (17 January 1916). Later

that year he illustrated James Oliver Curwood’s serial Western The Girl beyond the Trail (24 July to 24 September 1916), and in 1917 he created a headpiece for another

Howard essay about war and marriage (3 September 1917) as well as a full-color cover

of a young woman in eastern European folk costume (9 November 1917). Most notably

that year, Every Week commissioned a full-page drawing by Benda to illustrate a vignette from Laura de

Gozdawa Turczynowicz’s When the Prussians Came to Poland (1916), a memoir by an American woman married to a Polish man about her experiences

in occupied Poland. In Benda’s drawing, a woman and her children cower in the foreground

while dark figures in German helmets loom threateningly in the background (17 September

1917) (fig. 5). The memoir had been noted in “The Melting Pot” in May 1917,

Fig. 5. W.T. Benda’s illustration of a vignette from When the Prussians Came to Poland from Every Week magazine, 17 September 1917.W.T. Benda’s illustration of a vignette from When the Prussians Came to Poland from Every Week magazine, 17 September 1917.

suggesting that Benda’s vignette of the war in his homeland had been commissioned

in the spring.

Fig. 5. W.T. Benda’s illustration of a vignette from When the Prussians Came to Poland from Every Week magazine, 17 September 1917.W.T. Benda’s illustration of a vignette from When the Prussians Came to Poland from Every Week magazine, 17 September 1917.

suggesting that Benda’s vignette of the war in his homeland had been commissioned

in the spring.

Cather first suggested Benda to Houghton Mifflin as a potential illustrator forMy Ántonia in April 1917 (Cather to R. L. Scaife, 4 April 1917), but she took no further action until she had returned in October from Jaffrey, New Hampshire. She wrote to Scaife that she wanted headand tailpiece illustrations by Benda that closely followed her own ideas, or else no illustrations at all, and she anticipated inviting Benda to dinner to discuss illustrations (Cather to Scaife, 18 October 1917). Such a dinner certainly would have included Lewis, with whom Benda had an ongoing professional relationship. When Cather’s discussions with Houghton Mifflin about the cost of Benda’s services became heated, she defensively explained that she chose Benda because he knew both Bohemia and the American West (Cather to Ferris Greenslet, 24 November 1917)—a fact probably brought to her attention because Benda had made scenes and figures from both the American West and eastern Europe the subject of illustrations for Every Week. Neither Cather nor Scaife and Greenslet at Houghton Mifflin ever mention Lewis’s name in this extended epistolary argument, but Lewis’s active professional relationship with Benda and other magazine illustrators exerts a strong (if unnamed) pressure throughout.

Cather insists that Benda will complete the illustrations she envisions more cheaply for her than he would for anyone else, basing her claim on her experience with reselling serial illustrations to book publishers during her years at McClure’s (Cather to Greenslet, 24 November 1917). Scaife counters with an explanation—and complaint—about the difference between rates of compensation for book and magazine illustration. “In fact,” he writes, “in a good many cases, [magazines] have completely spoiled the artists, and have made it practically impossible for book publishers to use their work” (Scaife to Cather, 26 November 1917). Scaife’s complaint against magazines partially responds to Cather’s anecdote about McClure’s but also seems silently aimed at Lewis as an editor at Every Week. And perhaps Benda was willing to complete the illustrations for Cather’s novel cheaply because Lewis continued to send more lucrative magazine illustration work his way? Indeed, the October 1917 Bank Street dinner at which the novelist and the magazine editor entertained the illustrator to discuss illustrations for My Ántonia also likely led to Benda being further “spoiled” by Every Week with a new commission. In November, an editorial note— likely Lewis veiled by the editorial “we”—told readers how Benda came to contribute a drawing of Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski to its ongoing series, “The Most Interesting Man I Know.” “‘Who is the most interesting man you know?’ we asked Mr. Benda, and a few days later he appeared with this portrait, done from life. Mr. Benda is himself a Pole; and those who recall his picture, ‘When the Prussians Came to Poland,’ which appeared on this page some weeks ago, will find it easy to understand his intense feeling for his native land, and his admiration for the man who, more than any other, has contributed to its relief” (19 November 1917).

AFTER EVERY WEEK

The Crowell Publishing Co. voted Every Week out of existence in May 1918, citing war paper shortages as a determining cause (22 June 1918). Every Week thus did not survive to chronicle the armistice, the peace treaty, and the war’s aftermath— indeed, American troops were barely engaged in Europe when the staff produced its last issue. After twelve years of full-time magazine work, Lewis took a month’s vacation in Canada. In June 1918, Cather learned of the death of her cousin G. P. Cather on a French battlefield in May, and she spent part of the summer in Webster County, where she read G.P.’s letters to his mother and felt moved to write a novel about an American soldier like him. In November, as Cather was wrapping up My Ántonia, Lewis was applying for jobs, and in January 1919 she began her long career as an advertising copywriter at J. Walter Thompson.

Every Week continued to have significance in Lewis’s life long after its demise, as she continued to be a friend and mentor to the women and men who had worked under her. As Brenda Ueland wrote to Bruce Barton in 1930, “I like Edith Lewis so much and [she] has done so much for me by advice, money, and affection” (30 May 1930). After a few years of postwar wandering, John Mosher returned to New York in 1926 to join the staff of a new magazine, The New Yorker, and the warmth of his sustained relationship with his fellow Manhattanite Lewis comes through in Ueland’s report to Barton of a 1935 lunch. “I saw darling Edith Lewis,” she writes. “She took me and John Mosher to lunch at Voisin, and we drank too much and I can remember that through the fog John Mosher rebuked me saying that no one any more talked the way I did about ‘truth’ and ‘love.’ But Edith Lewis stuck up for me. She looked so elegant, so charming, like Countess Mend[e]l” (24 November 1935). Mosher died in 1942 at the age of fifty, and when an elderly Lewis wrote to Ueland in 1961, she recalled, “You were always my favorite of the Every Weekstaff—you and John Mosher, whom I was truly fond of, and whose early death I so regret.”

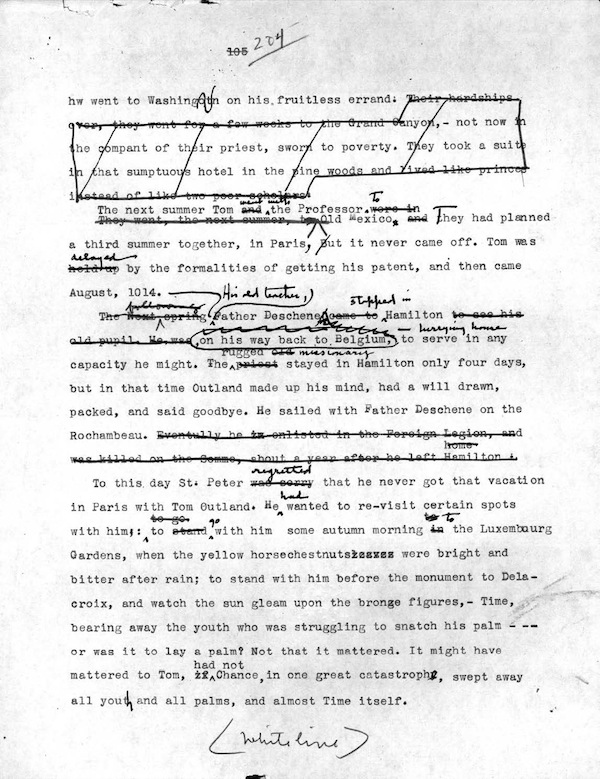

It is clear that, as Cather and Lewis moved forward together into the war years and

beyond, Lewis provided many forms of support (financial, editorial, emotional) crucial

to Cather’s emergence as a major creative artist. Since there are no known Cather

typescripts extant between “The Swedish Mother” and The Professor’s House (1925), there is an archival gap in the record of Lewis as Cather’s behind-the-scenes

editor. However, the surviving working typescript of The Professor’s House shows substantive revisions in Lewis’s hand, the quality and extent of which suggest

that it was not the first time she had done this sort of work on Cather’s fiction

(fig. 6). How should scholars interpret this evidence? Before most of the known typescripts

surfaced, Susan J. Rosowski argued that Cather’s move from Houghton

Fig. 6. A typescript page from The Professor’s House, edited by Edith Lewis. Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives

and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.A typescript page from The Professor’s House.

Mifflin to Knopf in the 1920s signified that Cather, the former magazine editor, was

“resum[ing] broad editorial responsibilities” in relation to her own fiction (19).

Quoting from her interview with Knopf himself about the treatment of Cather’s works

by his publishing house (“we didn’t do that kind of editing at all for Miss Cather”

[18]), Rosowski titles her essay “Willa Cather Editing Willa Cather.” Even in light

of the evidence of the typescripts, textual essays for the Willa Cather Scholarly

Edition have interpreted Lewis’s hand on the typescripts in secretarial terms (Lewis

was “serving as her amanuensis” and “transcri[bing] . . . revisions Cather wished to make” (Link, Obscure Destinies 338–39, emphasis added).[8]

Fig. 6. A typescript page from The Professor’s House, edited by Edith Lewis. Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives

and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.A typescript page from The Professor’s House.

Mifflin to Knopf in the 1920s signified that Cather, the former magazine editor, was

“resum[ing] broad editorial responsibilities” in relation to her own fiction (19).

Quoting from her interview with Knopf himself about the treatment of Cather’s works

by his publishing house (“we didn’t do that kind of editing at all for Miss Cather”

[18]), Rosowski titles her essay “Willa Cather Editing Willa Cather.” Even in light

of the evidence of the typescripts, textual essays for the Willa Cather Scholarly

Edition have interpreted Lewis’s hand on the typescripts in secretarial terms (Lewis

was “serving as her amanuensis” and “transcri[bing] . . . revisions Cather wished to make” (Link, Obscure Destinies 338–39, emphasis added).[8]

But Cather was not the only experienced magazine editor living at Five Bank Street—she shared a home with another editor who possessed considerable experience, skill, and judgment, and who inspired loyalty and admiration in those whose writing she supervised and edited. And, of particular consequence for One of Ours, Lewis’s years at Every Week gave her a deep knowledge of war news and literature, including war-related content that she edited for publication. When she picked up her pen at Five Bank Street, Lewis brought both an intimate knowledge of Cather’s fiction and the proper editorial distance from it. I do not propose to challenge the premise that Cather exercised final control over the end product (her published fiction), but the typescripts suggest that Knopf never needed to edit Cather’s fiction because Lewis had already subjected it to a thorough editing.[9] Although Cather maintained final authority over her texts, she welcomed Lewis’s involvement in her creative process, not as her secretary, but as her editor.