Cather Archive Publishing Cather's Early Journalism

In November of 1893, when she was only twenty years old, Willa Cather began her first writing career. In the pages of the Nebraska State Journal, where she had previously seen two school essays in print, she wrote a series of sketches under the heading "One Way of Putting It." "It is not the great, scholarly mind that does the great work," she wrote in that first column, "it is the man who knows a few things and loves them. A genius is just another way of defining a great enthusiast." Here, in the first column of her professional writing career, Cather was already beginning to form her major thesis about artistic achievement: greatness is built upon fierce desire.

In the columns that followed-reviews of traveling theatrical productions-Cather had the extraordinary opportunity to discuss the work of some of the most celebrated performers of the late nineteenth century. "Clara Morris," she writes, "acts by feeling alone. One can see her gestures and poses have never been practiced before a mirror. Sometimes they are almost grotesque in their violence, and her body writhes as though it were being literally torn asunder to let out the great soul within her." About the well-known comic actor William Crane, Cather writes, "Mr. Crane is an artist with a great heart. I don't know any higher praise to give him. His John Hackett is effective because he has warm blood in him. Romeo[s] and Hermanis sigh and sing and die the world over without half the genuine emotion and warmth that John Hackett had last night."

Despite her thrill at encountering world-class performers, Cather was not a gushy sycophant. After seeing a production of "Richelieu," she complained, "The main fault in [Walker Whiteside's] acting seems to be that he acts too much. He declaims constantly and hisses an invitation to dinner as though it were a summons to the block." In writing about the prevalence of newspaper "cynics," she claimed, "[i]f a man is a cynic he is so from a business standpoint. He is generally a good liver and thoroughly enjoys the company of the men he laughs at in his work, and when he dies it is generally from too much pastry rather than from a hatred of humanity."

Cather's journalism is rich with detailed accounts of the late nineteenth-century theatrical world, insights into the development of Cather's creative mind, and pithy commentary on art and culture. Yet this writing has never been completely collected, edited, and published in a form that makes it accessible to a wide readership. The Willa Cather Archive is trying to change that. In October 2005, the Archive published its first installment of the journalism, complete with multimedia annotations, full-text searchability, and digital images of the original page on which Cather's article appeared (cather.unl.edu/writings/journalism). The first installment-only seventeen of the nearly six hundred articles Cather published between 1891 and 1904-is merely a prototype of what the Archive is determined to achieve: the first complete edition of Cather's early journalism.

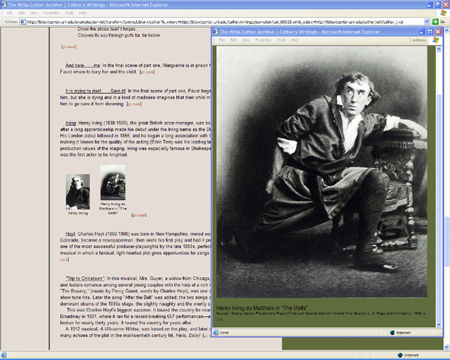

Kari Ronning, an experienced assistant editor of the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition, has partnered with myself and others in the Cather Project and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to create this digital edition. Ronning's annotations, which provide a context and background for Cather's articles, are both remarkable and extensive: for the first fifty-five articles transcribed, she has identified nearly 1500 names, titles, allusions, places, and cultural references for explication. Many of the notes contain both text and images, giving readers of the edition a visual sense of Cather's environment and the people she wrote about.

The edition is being created using Extensible Markup Language (XML) that conforms to the standards of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI). XML, the standard for all major digital editorial projects, allows the editors to "mark up" Cather's texts in order to record different intellectual features, from textual divisions to placement of figures and typographical errors. A major effort of the encoding is providing regularized names for all people and titles within the articles. This work, which has been done primarily by graduate student Jennifer Moore, allows for more accurate searching and other computational possibilities. For example, on the current prototype, one can search for "Morris" and retrieve all explicit mentions of Clara Morris and Cather's more oblique references to her, as when she writes of the "passionate tones of the great actress." Some day, when a sufficient number of articles have been fully transcribed and encoded, this encoding will allow for automatic indexing of Cather writing (i.e., generating a list of all people or literary titles mentioned in her journalism) as well as many other forms of analysis.

The speed at which this edition is completed depends greatly on the outcome of a pending funding proposal. However, if the proposal is successful, we plan to complete the full edition of the journalism by the summer of 2009.

We believe that our digital edition will encourage widespread and well-informed scholarly attention to Cather's journalistic career for the first time. Like Whitman, Twain, Hemingway, Dos Passos, Crane, and others, Cather is a major American author that learned her craft while filling the columns of a newspaper. Her journalistic work is remarkable for its vivaciousness, insight, and humor, and we hope this digital edition will finally give it the attention it deserves.