The Sombrero

by Willa Cather

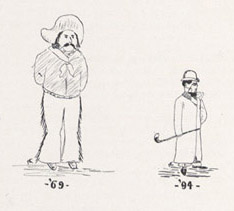

From The Sombrero, (1895): 224-231.

"The Fear That Walks By Noonday."

(First Prize Story.)"WHERE is my shin guard? Horton, you lazy dog, get your duds off, won't you? Why didn't you dress at the hotel with the rest of us? There's got to be a stop to your blamed eccentricities some day," fumed Reggie, hunting wildly about in a pile of overcoats.

Horton began pulling off his coat with that air of disinterested deliberation he always assumed to hide any particular nervousness. He was to play two positions that day, both half and full, and he knew it meant stiff work.

"What do you think of the man who plays in Morrison's place, Strike?" he asked as he took off his shoes.

"I can tell you better in about half an hour; I suppose the 'Injuns' knew what they were about when they put him there."

"They probably put him there because they hadn't another man who could even look like a full back. He played quarter badly enough, if I remember him."

"I don't see where they get the face to play us at all. They would never have scored last month if it hadn't been for Morrison's punting. That fellow played a great game, but the rest of them are light men, and their coach is an idiot. That man would have made his mark if he'd lived. He could play different positions just as easily as Chum-Chum plays different roles—pardon the liberty, Fred—and then there was that awful stone wall strength of his to back it; he was a mighty man."

"If you are palpitating to know why the 'Injuns' insist on playing us, I'll tell you; it's for blood. Exhibition game be damned! It's to break our bones they're playing. We were surprised when they didn't let down on us harder as soon as the fellow died, but they have been cherishing their wrath, they haven't lost an ounce of it, and they are going into us to-day for vengeance."

"Well, their sentiments are worthy, but they haven't got the players."

"Let up on Morrison there, Horton," shouted Reggie, "we sent flowers and sympathies at the time, but we are not going to lose this game out of respect to his memory: shut up and get your shin guard on. I say, Nelson, if you don't get out of here with that cigarette I'll kick you out. I'll get so hungry I'll break training rules. Besides, the coach will be in here in a minute going around smelling our breaths like ourmammas used to do, if he catches a scent of it. I'm humming glad it's the last week of training; I couldn't stand another day of it. I brought a whole pocket full of cigars, and I'll have one well under way before the cheering is over. Won't we see the town tonight, Freddy?"

Horton nodded and laughed one of his wicked laughs. "Training has gone a shade too far this season. It's all nonsense to say that nobody but hermits and anchorites can play foot ball. A Methodist parson don't have to practice half such rigid abstinence as a man on the eleven." And he kicked viciously at the straw on the floor as he remembered the supper parties he had renounced, the invitations he had declined, and the pretty faces he had avoided in the last three months.

"Five minutes to three!" said the coach, as he entered, pounding on the door with his cane. Strike began to hunt frantically for the inflater, one of the tackles went striding around the room seeking his nose protector with lamentations and profanity, and the rest of the men got on their knees and began burrowing in the pile of coats for things they had forgotten to take out of their pockets. Reggie began to hurry his men and make the usual encouraging remarks to the effect that the universe was not created to the especial end that they should win that foot ball game, that the game was going to the men who kept the coolest heads and played the hardest ball. The coach rapped impatiently again, and Horton and Reggie stepped out together, the rest following them. As soon as Horton heard the shouts which greeted their appearance, his eyes flashed, and he threw his head back like a cavalry horse that hears the bugle sound a charge. He jumped over the ropes and ran swiftly across the field, leaving Reggie to saunter along at his leisure, bowing to the ladies in the grand stand and on the tally-hos as he passed.

When he reached the lower part of the field he found a hundred Marathon college men around the team yelling and shouting their encouragement. Reggie promptly directed the policemen to clear the field, and, taking his favorite attitude, his feet wide apart and his body very straight, he carelessly tossed the quarter into the air.

"Line 'em up, Reggie, line 'em up. Let us into it while the divine afflatus lasts," whispered Horton.

The men sprang to their places, and Reggie forgot the ladies on the tally-hos; the color came to his face, and he drew himself up and threw every sinew of his little body on a tension. The crowd outside began to cheer again, as the wedge started off for north goal. The western men were poor on defensive work, and the Marathon wedge gained ground on the first play. The first impetus of success was broken by Horton fumbling and losing the ball. The eleven looked rather dazed at this, and Horton was the most dazed looking man of them all, for he did not indulge in that kind of thing often. Reggie could scarcely believe his senses, and stood staring at Horton in unspeakable amazement, but Horton only spread out his hands and stared at them as though to see if they were still there. There was little time for reflection or conjecture. The western men gave their Indian yell and prepared to play; their captain sang out his signals, and the rushing began. In spite of the desperate resistance on the part of Reggie's men, the ball went steadily south, and in twelve minutes the "Injuns" had scored. No one quite knew how they did it, least of all their bewildered opponents. They did some bad fumbling on the five-yard line, but though Reggie's men fell all over the ball, they did not seem to be able to take hold of it.

"Call in a doctor," shouted Reggie; "they're paralyzed in the arms, every one of 'em."

Time was given to bandage a hurt, and half a dozen men jumped over the ropes and shot past the policemen and rushed up to Reggie, pitifully asking what the matter was.

"Matter! I don't know! They're all asleep or drunk. Go kick them, pound them, anything to get them awake." And the little captain threw his sweater over his shoulder and swore long and loud at all mankind in general and Frederick Horton in particular. Horton turned away without looking at him. He was a younger man than Reggie, and, although he had had more experiences, they were not of the kind that counted much with the men of the eleven. He was very proud of being the captain's right-hand man, and it cut him hard to fail him.

"I believe I've been drugged, Black," he said, turning to the right tackle. "I am as cold as ice all over and I can't use my arms at all; I've a notion to ask Reggie to call in a sub."

"Don't, for heaven's sake, Horton; he is almost frantic now; believe it would completely demoralize the team; you have never laid off since you were on the eleven, and if you should now when you have no visible hurt it would frighten them to death."

"I feel awful, I am so horribly cold."

"So am I, so are all the fellows; see how the "Injuns" are shivering over there, will you? There must be a cold wave; see how Strike's hair is blowing down in his eyes." "The cold wave seems to be confined to our locality," remarked Horton in a matter-of-fact way; but in somewhat strained tones. "The girls out there are all in their summer dresses without wraps, and the wind which is cutting our faces all up don't even stir the ribbon on their hats."

"Y-a-s, horribly draughty place, this," said Black blankly.

"Horribly, draughty as all out doors," said Horton with a grim laugh.

"Bur-r-r!" said Strike, as he handed his sweater over to a substitute and took his last pull at a lemon, "this wind is awful; I never felt anything so cold; it's a raw, wet cold that goes clear into the marrow of a fellow's bones. I don't see where it comes from; there is no wind outside the ropes apparently."

"The winds blow in such strange directions here," said Horton, picking up a straw and dropping it. "It goes straight down with force enough to break several camels' backs."

"Ugh! it's as though the firmament had sprung a leak and the winds were sucking in from the other side."

"Shut your mouths, both of you," said Reggie, with an emphatic oath. "You will have them all scared to death; there's a panic now, that's what's the matter, one of those quiet, stupid panics that are the worst to manage. Laugh, Freddie, laugh hard; get up some enthusiasm; come you, shut up, if you can't do any better than that. Start the yell, Strike, perhaps that will fetch them."

A weak yell that sounded like an echo rose from the field and the Marathon men outside the ropes caught it up and cheered till the air rang. This seemed torouse the men on the field, and they got to their places with considerable energy. Reggie gave an exultant cry, as the western men soon lost the ball, and his men started it north and kept steadily gaining. They were within ten yards of the goal, when suddenly the ball rose serenely out of a mass of struggling humanity and flew back twenty, forty, sixty, eighty yards toward the southern goal! But the half was versed in his occupation; he ran across and stood under the ball, waiting for it with outstretched arms. It seemed to Horton that the ball was all day in falling; it was right over him and yet it seemed to hang back from him, like Chum-Chum when she was playing with him. With an impatient oath he ground his teeth together and bowed his body forward to hold it with his breast, and even his knees if need be, waiting with strength and eagerness enough in his arm to burst the ball to shreds. The crowd shouted with delight, but suddenly caught its breath; the ball fell into his arms, between them, through them, and rolled on the ground at his feet. Still he stood there with his face raised and his arms stretched upward in an attitude ridiculously suggestive of prayer. The men rushed fiercely around him shouting and reviling; his arms dropped like lead to his side, and he stood without moving a muscle, and in his face there was a look that a man might have who had seen what he loved best go down to death through his very arms, and had not been able to close them and save. Reggie came up with his longest oaths on his lip, but when he saw Horton's face he checked himself and said with that sweetness of temper that always came to him when he saw the black bottom of despair,

"Keep quiet, fellows, Horton's all right, only he is a bit nervous." Horton moved for the first time and turned on the little captain, "You can say anything else you like, Reggie, but if you say I am scared I'll knock you down."

"No, Fred, I don't mean that; we must hang together, man, every one of us, there are powers enough against us," said Reggie, sadly. The men looked at each other with startled faces. So long as Reggie swore there was hope, but when he became gentle all was lost.

In another part of the field another captain fell on his fullback's neck and cried, "Thomas, my son, how did you do it? Morrison in his palmiest days never made a better lift than that."

"I-I didn't do it, I guess; some of the other fellows did; Towmen, I think."

"Not much I didn't," said Towmen, "you were so excited you didn't know what you were doing. You did it, though; I saw it go right up from your foot."

"Well, it may be," growled the "Injun" half, "but when I make plays like that I'd really like to be conscious of them. I must be getting to be a darned excitable individual if I can punt eighty yards and never know it."

"Heavens! how cold it is. This is a great game, though; I don't believe they'll score."

"I don't; they act like dead men; I would say their man Horton was sick or drunk if all the others didn't act just like him."

The "Injuns" lost the ball again, but when Reggie's men were working it north the same old punting scheme was worked somewhere by someone in the "Injuns"' ranks. This time Amack, the right half, ran bravely for it; but when he was almost beneath it he fell violently to the ground, for no visible reason, and lay there strug-gling like a man in a fit. As they were taking him off the field, time was called for the first half. Reggie's friends and several of his professors broke through the gang of policemen and rushed up to him. Reggie stepped in front of his men and spoke to the first man who came up, "If you say one word or ask one question I'll quit the field. Keep away from me and from my men. Let us alone." The paleness that showed through the dirt on Reggie's face alarmed the visitors, and they went away as quickly as they had come. Reggie and his men lay down and covered themselves with their overcoats, and lay there shuddering under that icy wind that sucked down upon them. The men were perfectly quiet and each one crept off by himself. Even the substitutes who brought them lemons and water did not talk much; they had neither disparagement nor encouragement to offer; they sat around and shivered like the rest. Horton hid his face on his arm and lay like one stunned. He muttered the score, 18 to 0, but he did not feel the words his lips spoke, nor comprehend them. Like most dreamy, imaginative men, Horton was not very much at home in college. Sometimes in his loneliness he tried to draw near to the average man, and be on a level with him, and in so doing made a consummate fool of himself, as dreamers always do when they try to get themselves awake. He was awkward and shy among women, silent and morose among men. He was tolerated in the societies because he could write good poetry, and in the clubs because he could play foot ball. He was very proud of his accomplishments as a halfback, for they made him seem like other men. However ornamental and useful a large imagination and sensitive temperament may be to a man of mature years, to a young man they are often very like a deformity which he longs to hide. He wondered what the captain would think of him and groaned. He feared Reggie as much as he adored him. Reggie was one of those men who, by the very practicality of their intellects, astonish the world. He was a glorious man for a college. He was brilliant, adaptable, and successful; yet all his brains he managed to cover up by a pate of tow hair, parted very carefully in the middle, and his iron strength was generally very successfully disguised by a very dudish exterior. In short, he possessed the one thing which is greater than genius, the faculty of clothing genius in such boundless good nature that it is offensive to nobody. Horton felt to a painful degree his inferiority to him in most things, and it was not pleasant to him to lose ground in the one thing in which he felt they could meet on an equal footing. Horton turned over and looked up at the leaden sky, feeling the wind sweep into his eyes and nostrils. He looked about him and saw the other men all lying down with their heads covered, as though they were trying to get away from the awful cold and the sense of Reggie's reproach. He wondered what was the matter with them; whether they had been drugged or mesmerized. He tried to remember something in all the books he had read that would fit the case, but his memory seemed as cold and dazed as the rest of him; he only remembered some hazy Greek, which read to the effect that the gods sometimes bring madness upon those they wish to destroy. And here was another proof that the world was going wrong—it was not a normal thing for him to remember any Greek.

He was glad when at last he heard Reggie's voice calling the men together; he went slowly up to him and said rather feebly, "I say, a little brandy wouldn't hurt us, would it? I am so awfully cold I don't know what the devil is the matter with me, Reggie, my arms are so stiff I can't use 'em at all."

Reggie handed him a bottle from his grip, saying briefly, "It can't make things any worse."

In the second half the Marathon men went about as though they were walking in their sleep. They seldom said anything, and the captain was beyond coaxing or swearing; he only gave his signals in a voice as hollow as if it came from an empty church. His men got the ball a dozen times, but they always lost it as soon as they got it, or, when they had worked it down to one goal the "Injuns" would punt it back to the other. The very spectators sat still and silent, feeling that they were seeing something strange and unnatural. Every now and then some "Injun" would make a run, and a Marathon man would dash up and run beside him for a long distance without ever catching him, but with his hands hanging at his side. People asked the physicians in the audience what was the matter; but they shook their heads.

It was at this juncture that Freddie Horton awoke and bestirred himself. Horton was a peculiar player; he was either passive or brilliant. He could not do good line work; he could not help other men play. If he did anything he must take matters into his own hands, and he generally did; no one in the northwest had ever made such nervy, dashing plays as he; he seemed to have the faculty of making sensational and romantic situations in foot ball just as he did in poetry. He played with his imagination. The second half was half over, and as yet he had done nothing but blunder. His honor and the honor of the team had been trampled on. As he thought of it the big veins stood out in his forehead and he set his teeth hard together. At last his opportunity came, or rather he made it. In a general scramble for the ball he caught it in his arms and ran. He held the ball tight against his breast until he could feel his heart knocking against the hard skin; he was conscious of nothing but the wind whistling in his ears and the ground flying under his feet, and the fact that he had ninety yards to run. Both teams followed him as fast as they could, but Horton was running for his honor, and his feet scarcely touched the earth. The spectators, who had waited all afternoon for a chance to shout, now rose to their feet and all the lungs full of pent-up enthusiasm burst forth. But the gods are not to be frustrated for a man's honor or his dishonor, and when Freddie Horton was within ten yards of the goal he threw his arms over his head and leaped into the air and fell. When the crowd reached him they found no marks of injury except the blood and foam at his mouth where his teeth had bitten into his lip. But when they looked at him the men of both teams turned away shuddering. His knees were drawn up to his chin; his hands were dug into the ground on either side of him; his face was the livid, bruised blue of a man who dies with apoplexy; his eyes were wide open and full of unspeakable horror and fear, glassy as ice, and still as though they had been frozen fast in their sockets.

It was an hour before they brought him to, and then he lay perfectly silent and would answer no questions. When he was stretched obliquely across the seats of a carriage going home he spoke for the first time.

"Give me your hand, Reggie; for God's sake let me feel something warm and human. I am awful sorry, Reggie; I tried for all my life was worth to make that goal, but—" he drew the captain's head down to his lips and whispered something that made Reggie's face turn white and the sweat break out on his forehead. He drew big Horton's head upon his breast and stroked it as tenderly as a woman.

PART II

There was silence in the dining room of the Exeter House that night when the waiters brought in the last course. The evening had not been a lively one. The defeated men were tired with that heavy weariness which follows defeat, and the victors seemed strained and uneasy in their manners. They all avoided speaking of the game and forced themselves to speak of things they could not fix their minds upon. Reggie sat at the head of the table correct and faultless. Reggie was always correct, but to-night there was very little of festal cheer about him. He was cleanly shaved, his hair was parted with the usual mathematical accuracy. A little strip of black court plaster covered the only external wound defeat had left. But his face was as white as the spotless expanse of his shirt bosom, and his eyes had big black circles under them like those of a man coming down with the fever. All evening he had been nervous and excited; he had not eaten anything and was evidently keeping something under. Every one wondered what it was, and yet feared to hear it. When asked about Horton he simply shuddered, mumbled something, and had his wine glass filled again.

Laughter or fear are contagious, and by the time the last course was on the table every one was as nervous as Reggie. The talk started up fitfully now and then but it soon died down, and the weakly attempts at wit were received in silence.

Suddenly every one became conscious of the awful cold and inexplicable downward draught that they had felt that afternoon. Every one was determined not to show it. No one pretended to even notice the flicker of the gas jets, and the fact that their breath curled upward from their mouths in little wreaths of vapor. Every one turned his attention to his plate and his glass stood full beside him. Black made some remarks about politics, but his teeth chattered so he gave it up. Reggie's face was working nervously, and he suddenly rose to his feet and said in a harsh, strained voice,

"Gentlemen, you had one man on your side this afternoon who came a long journey to beat us. I mean the man who did that wonderful punting and who stood before the goal when Mr. Horton made his run. I propose the first toast of the evening to the twelfth man, who won the game. Need I name him?"

The silence was as heavy as before. Reggie extended his glass to the captain beside him, but suddenly his arm changed direction; he held the glass out over the table and tipped it in empty air as though touching glasses with some one. The sweat broke out on Reggie's face; he put his glass to his lips and tried to drink, but only succeeded in biting out a big piece of the rim of his wine glass. He spat the glass out quickly upon his plate and began to laugh, with the wine oozing out between his white lips.Then everyone laughed; leaning upon each other's shoulders, they gave way to volleys and shrieks of laughter, waving their glasses in hands that could scarcely hold them. The negro waiter, who had been leaning against the wall asleep, came forward rubbing his eyes to see what was the matter. As he approached the end of the table he felt that chilling wind, with its damp, wet smell like the air from a vault, and the unnatural cold that drove to the heart's center like a knife blade.

"My Gawd!" he shrieked, dropping his tray, and with an inarticulate gurgling cry he fled out of the door and down the stairway with the banqueters after him, allbut Reggie, who fell to the floor, cursing and struggling and grappling with the powers of darkness. When the men reached the lower hall they stood without speaking, holding tightly to each other's hands like frightened children. At last Reggie came down the stairs, steadying himself against the banister. His dress coat was torn, his hair was rumpled down over his forehead, his shirt front was stained with wine, and the ends of his tie were hanging to his waist. He stood looking at the men and they looked at him, and no one spoke.

Presently a man rushed into the hall from the office and shouted "McKinley has carried Ohio by eighty-one thousand majority!" and Regiland Ashton, the product of centuries of democratic faith and tradition, leaped down the six remaining stairs and shouted, "Hurrah for Bill McKinley."

In a few minutes the men were looking for a carriage to take Regiland Ashton home.