The Professor's House

The Willa Cather Scholarly Edition

with Kari A. Ronning

CONTENTS

Preface

The objective of the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition is to provide to readers — present and future — various kinds of information relevant to Willa Cather's writing, obtained and presented according to the highest scholarly standards: a critical text faithful to her intention as she prepared it for the first edition, a historical essay providing relevant biographical and historical facts, explanatory notes identifying allusions and references, a textual commentary tracing the work through its lifetime and describing Cather's involvement with it, and a record of changes in the text's various versions. This edition is distinctive in the comprehensiveness of its apparatus, especially in its inclusion of extensive explanatory information that illuminates the fiction of a writer who drew so extensively upon actual experience, as well as the full textual information we have come to expect in a modern critical edition. It thus connects activities that are too often separate—literary scholarship and textual editing.

Editing Cather's writing means recognizing that Cather was as fiercely protective of her novels as she was of her private life. She suppressed much of her early writing and dismissed serial publication of later work, discarded manuscripts and proofs, destroyed letters, and included in her will a stipulation against publication of her private papers. Yet the record remains surprisingly full. Manuscripts, typescripts, and proofs of some texts survive with corrections and revisions in Cather's hand; serial publications provide final "draft" versions of texts; correspondence with her editors and publishers help clarify her intention for a work, and publishers' records detail each book's public life; correspondence with friends and acquaintances provides an intimate view of her writing; published interviews with and speeches by Cather provide a running public commentary on her career; and through their memoirs, recollections, and letters, Cather's contemporaries provide their own commentary on circumstances surrounding her writing.

In assembling pieces of the editorial puzzle, we have been guided by principles and procedures articulated by the Committee on Scholarly Editions of the Modern Language Association. Assembling and comparing texts demonstrated the basic tenet of the textual editor̬that only painstaking collations reveal what is actually there. Scholars had assumed, for example, that with the exception of a single correction in spelling, O Pioneers! passed unchanged from the 1913 first edition to the 1937 Autograph Edition. Collations revealed nearly a hundred word changes, thus providing information not only necessary to establish a critical text and to interpret how Cather composed, but also basic to interpreting how her ideas about art changed as she matured.

Cather's revisions and corrections on typescripts and page proofs demonstrate that she brought to her own writing her extensive experience as an editor. Word changes demonstrate her practices in revising; other changes demonstrate that she gave extraordinarily close scrutiny to such matters as capitalization, punctuation, paragraphing, hyphenation, and spacing. Knowledgeable about production, Cather had intentions for her books that extended to their design and manufacture. For example, she specified typography, illustrations, page format, paper stock, ink color, covers, wrappers, and advertising copy.

To an exceptional degree, then, Cather gave to her work the close textual attention that modern editing practices respect, while in other ways she challenged her editors to expand the definition of "corruption" and "authoritative" beyond the text, to include the book's whole format and material existence. Believing that a book's physical form influenced its relationship with a reader, she selected type, paper, and format that invited the reader response she sought. The heavy texture and cream color of paper used for O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, for example, created a sense of warmth and invited a childlike play of imagination, as did these books' large dark type and wide margins. By the same principle, she expressly rejected the anthology format of assembling texts of numerous novels within the covers of one volume, with tight margins, thin paper, and condensed print.

Given Cather's explicitly stated intentions for her works, printing and publishing decisions that disregard her wishes represent their own form of corruption, and an authoritative edition of Cather must go beyond the sequence of words and punctuation to include other matters: page format, paper stock, typeface, and other features of design. The volumes in the Cather Edition respect those intentions insofar as possible within a series format that includes a comprehensive scholarly apparatus. For example, the Cather Edition has adopted the format of six by nine inches, which Cather approved in Bruce Rogers's elegant work on the 1937 Houghton Mifflin Autograph Edition, to accommodate the various elements of design. While lacking something of the intimacy of the original page, this size permits the use of large, generously leaded type and ample margins—points of style upon which the author was so insistent. In the choice of paper, we have deferred to Cather's declared preference for a warm, cream antique stock.

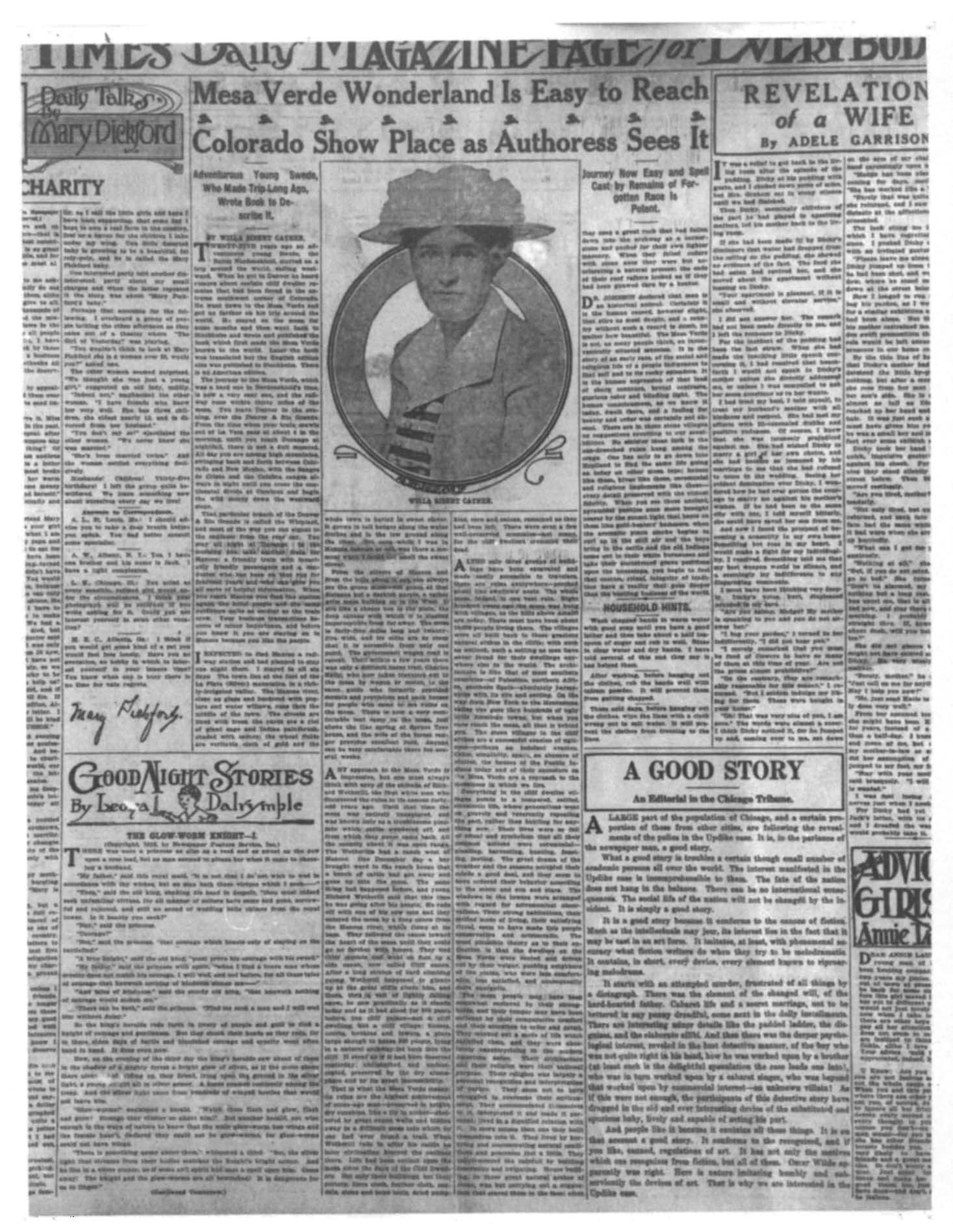

Today's technology makes it difficult to emulate the qualities of hot-metal typesetting and letterpress printing. In comparison, modern phototypesetting printed by offset lithography tends to look anemic and lacks the tactile quality of type impressed into the page. The version of the Caslon Old Face type employed in the original edition of The Professor's House, were it available for phototypesetting, would hardly survive the transition. Instead, we have chosen Linotype Janson Text, a modern rendering of the type used by Rogers. The subtle adjustments of stroke weight in this reworking do much to retain the integrity of earlier metal versions. Therefore, without trying to replicate the design of single works, we seek to represent Cather's general preferences in a design that encompasses many volumes.

In each volume in the Cather Edition, the author's specific intentions for design and printing are set forth in textual commentaries. These essays also describe the history of the texts, identify those that are authoritative, explain the selection of copy-texts or basic texts, justify emendations of the copy-text, and describe patterns of variants. The textual apparatus in each volume—lists of variants, emendations, explanations of emendations, and end-line hyphenations—completes the textual story.

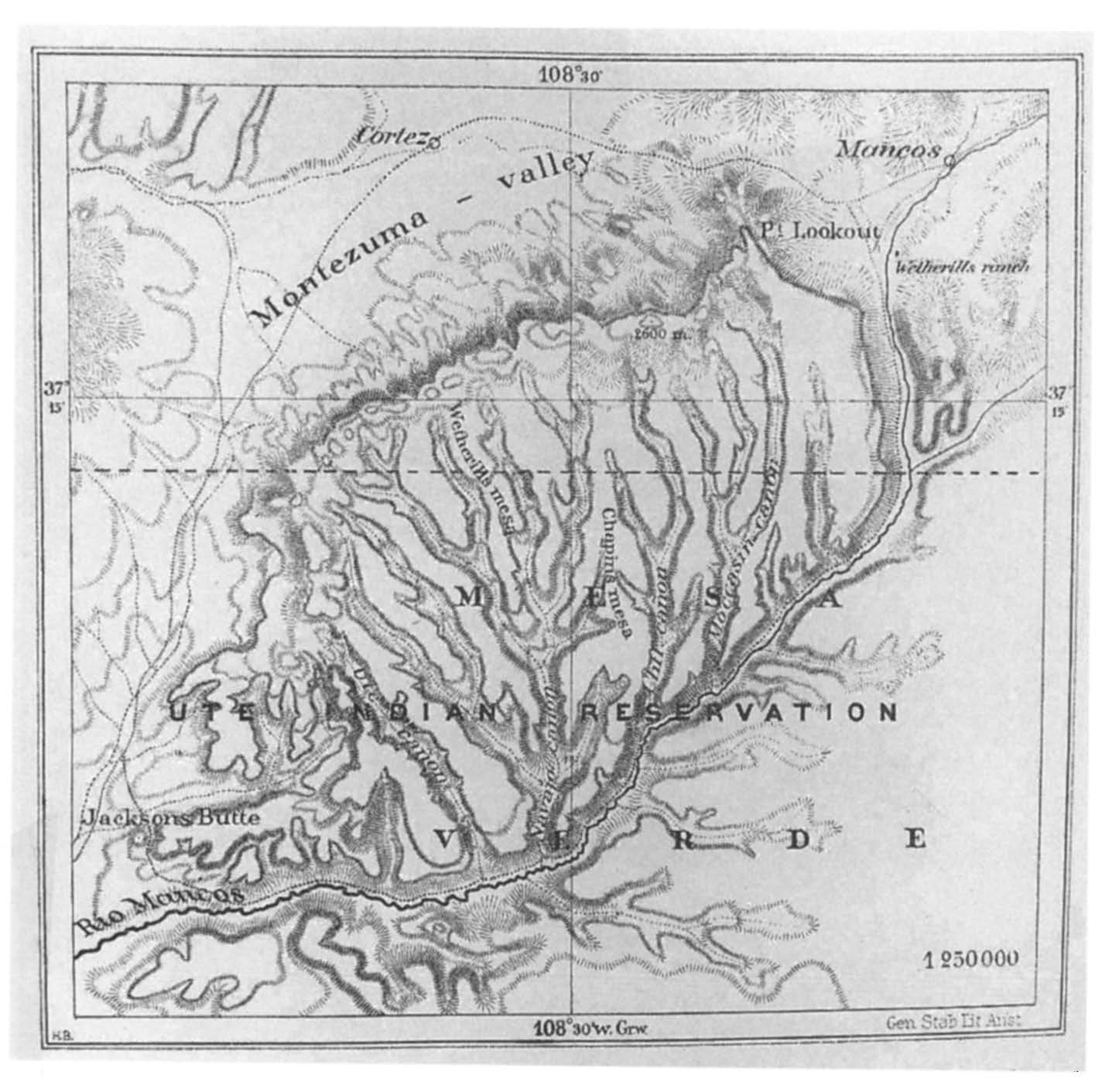

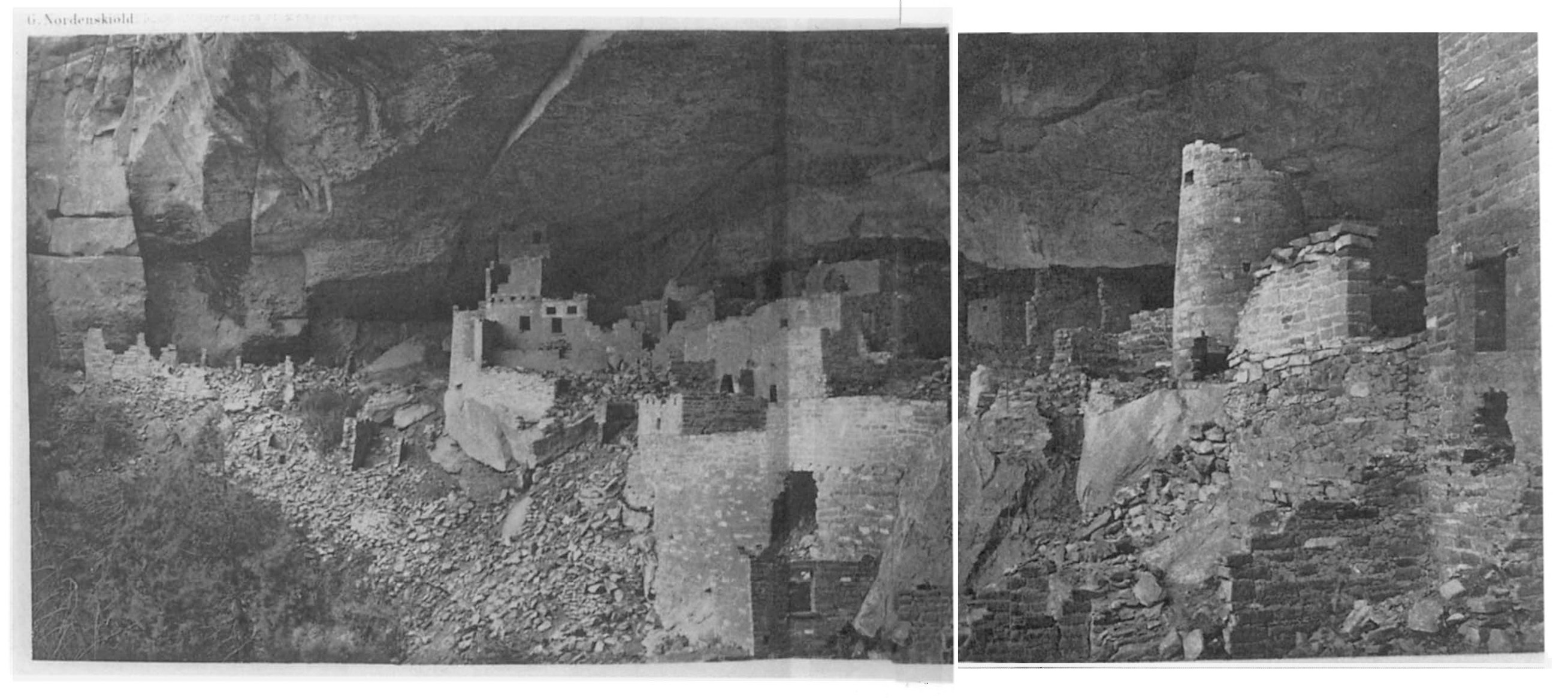

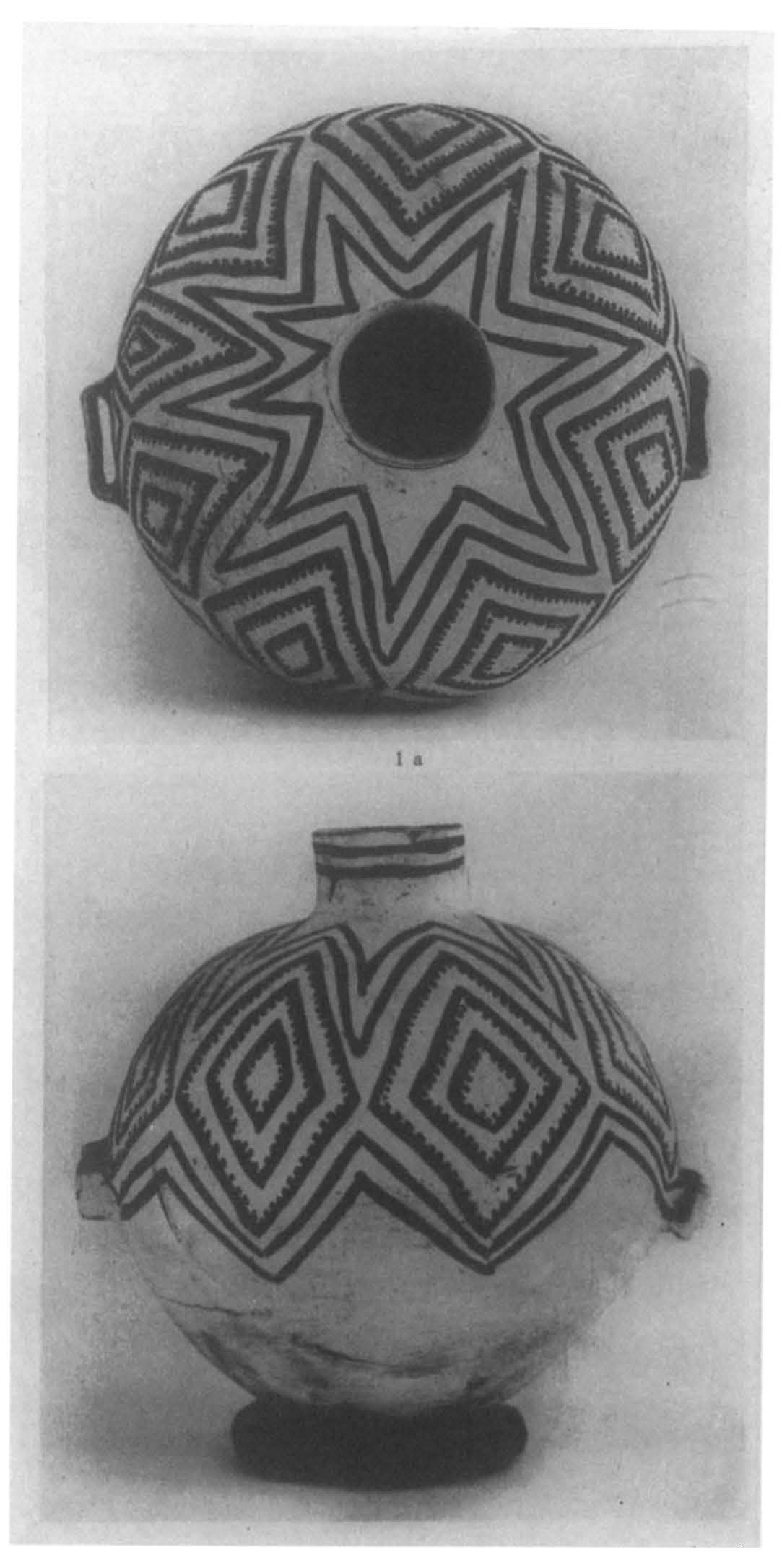

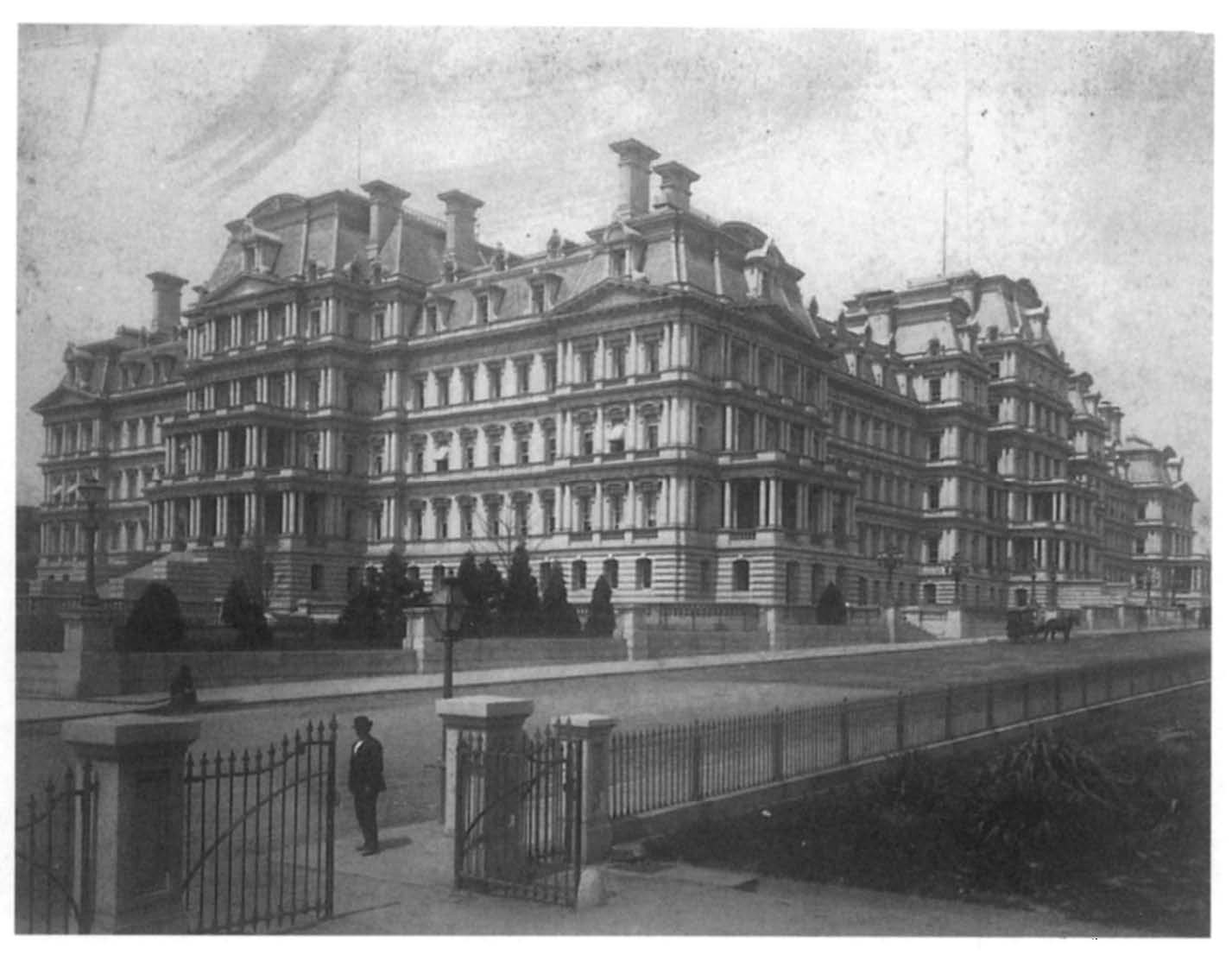

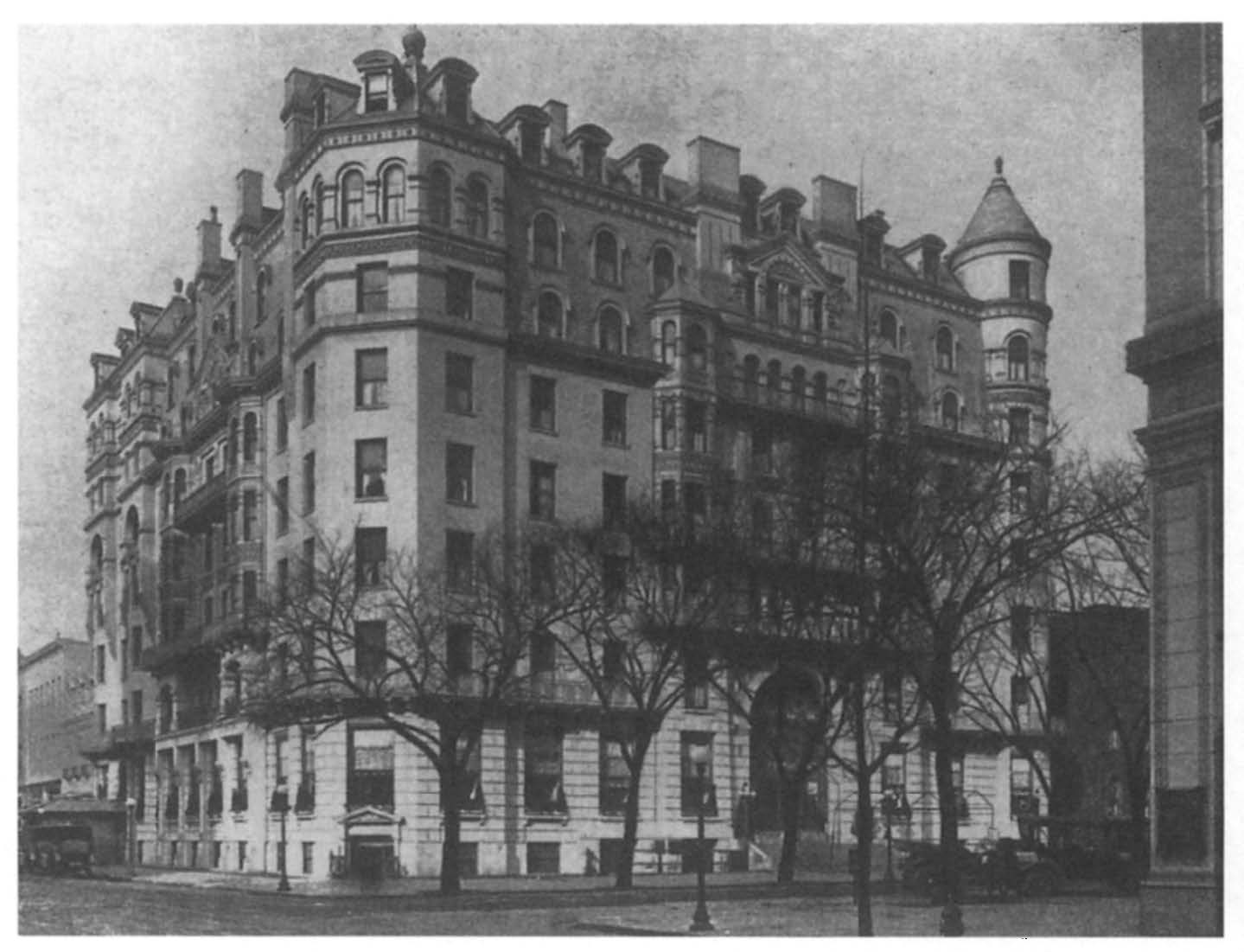

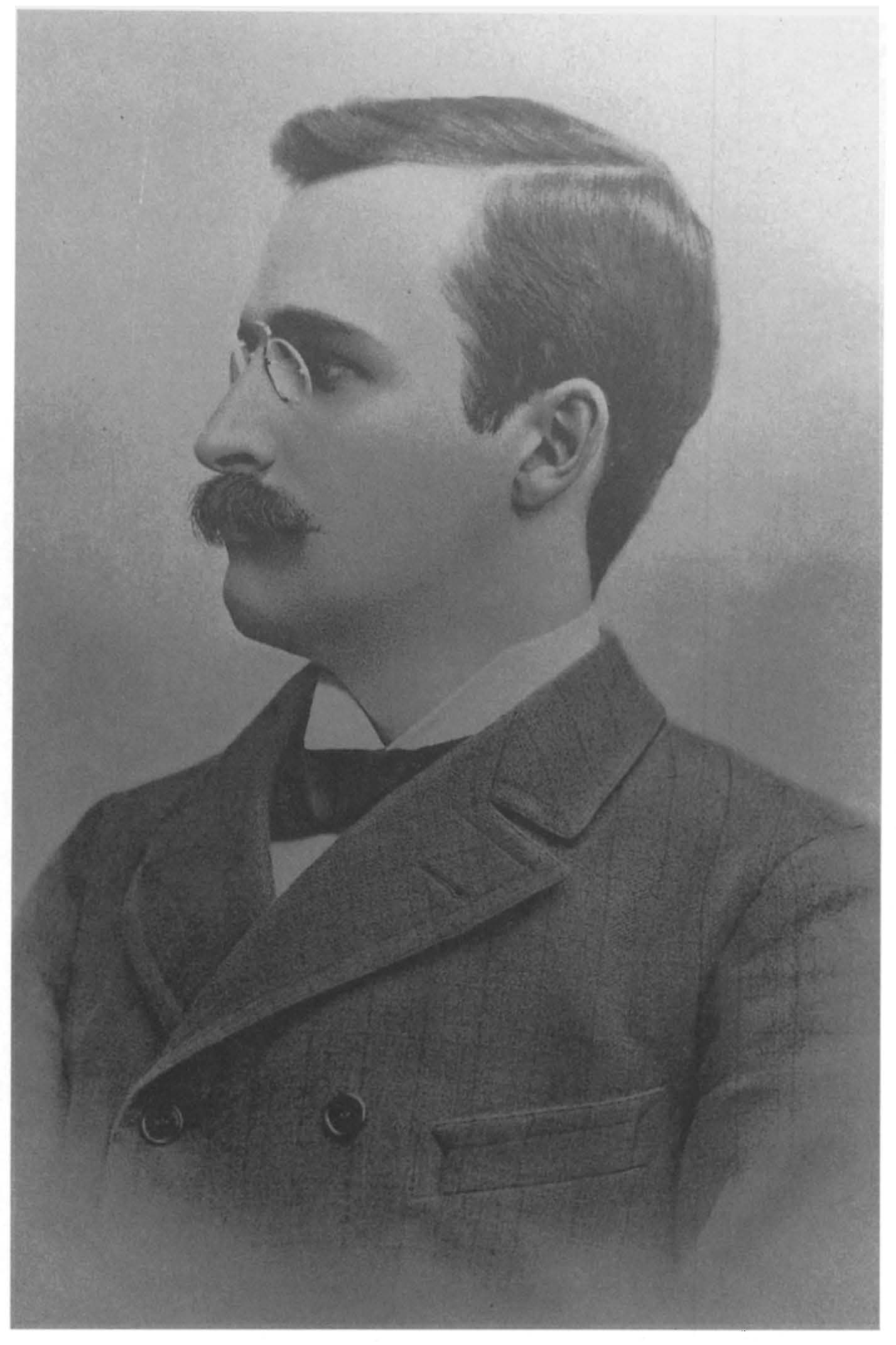

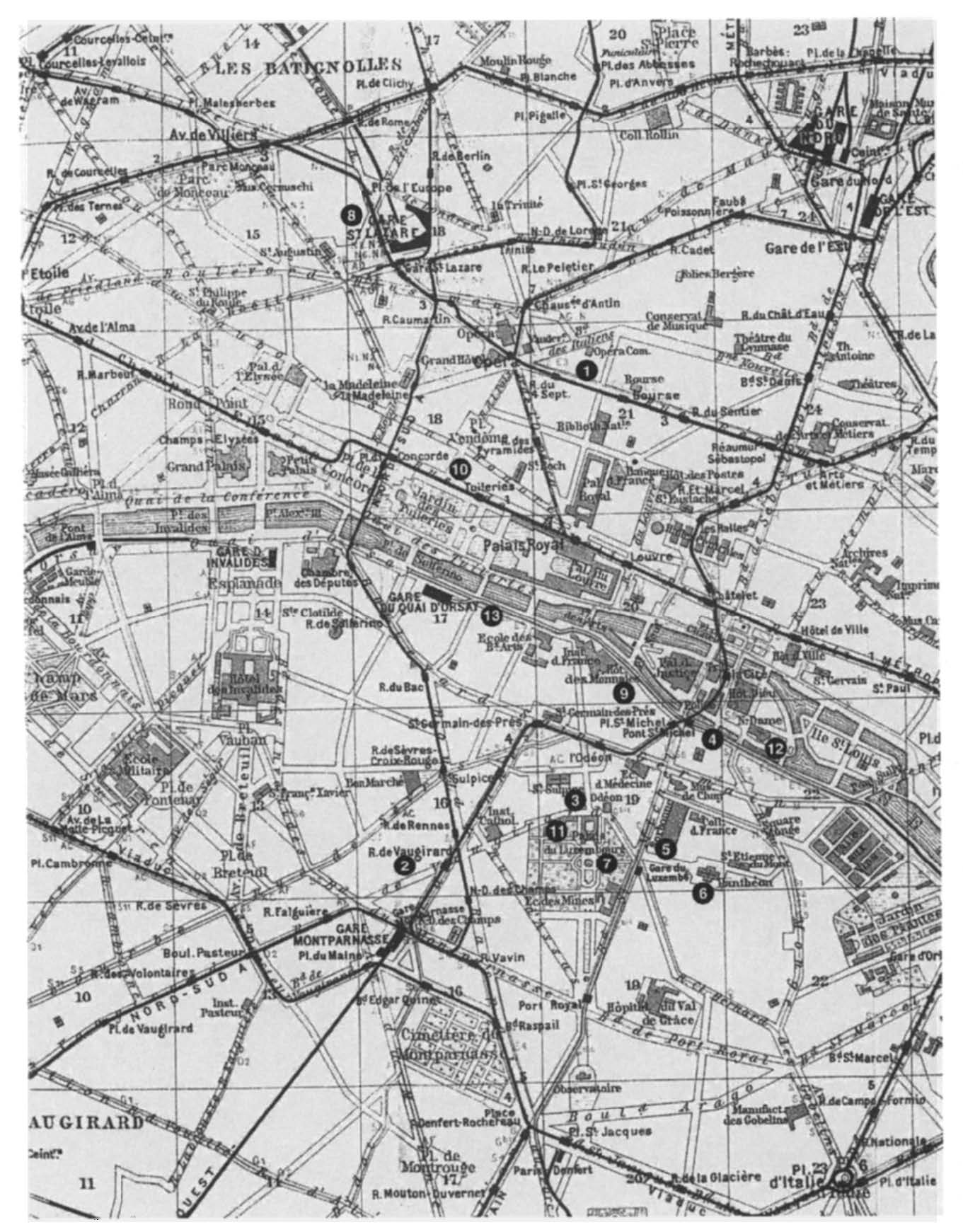

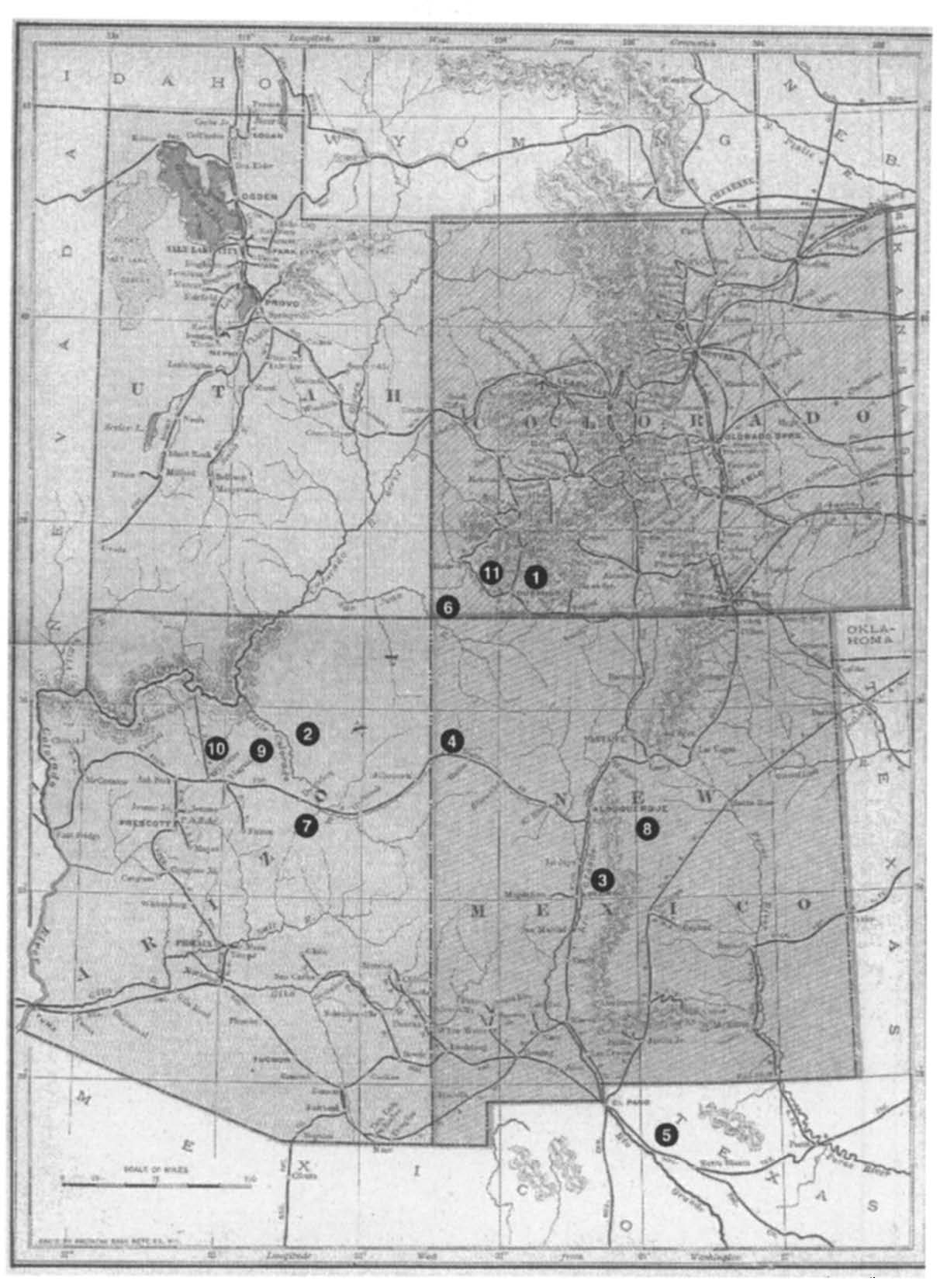

Historical essays provide essential information about the genesis, form, and transmission of each book, as well as supply its biographical, historical, and intellectual contexts. Illustrations supplement these essays with photographs, maps, and facsimiles of manuscript, typescript, or typeset pages. Finally, because Cather in her writing drew so extensively upon personal experience and historical detail, explanatory notes are an especially important part of the Cather Edition. By providing a comprehensive identification of her references to flora and fauna, to regional customs and manners, to the classics and the Bible, to popular writing, music, and other arts—as well as relevant cartography and census material—these notes provide a starting place for scholarship and criticism on subjects long slighted or ignored.

Within this overall standard format, differences occur that are informative in their own right. The straightforward textual history of O Pioneers! and My Ántonia contrasts with the more complicated textual challenges of A Lost Lady and Death Comes for the Archbishop; the allusive personal history of the Nebraska novels, so densely woven that My Ántonia seems drawn not merely upon Anna Pavelka but upon all of Webster County, contrasts with the more public allusions of novels set elsewhere. The Cather Edition reflects the individuality of each work while providing a standard of reference for critical study.

The Professor's House

1

Book One

The Family

I

The moving was over and done. Professor St. Peter was alone in the dismantled house where he had lived ever since his marriage, where he had worked out his career and brought up his two daughters. It was almost as ugly as it is possible for a house to be; square, three stories in height, painted the colour of ashes—the front porch just too narrow for comfort, with a slanting floor and sagging steps. As he walked slowly about the empty, echoing rooms on that bright September morning, the Professor regarded thoughtfully the needless inconveniences he had put up with for so long; the stairs that were too steep, the halls that were too cramped, the awkward oak mantels with thick round posts crowned by bumptious wooden balls, over green-tiled fire-places.

Certain wobbly stair treads, certain creaky boards in the upstairs hall, had made him wince many times a day for twenty-odd years—and they still creaked and wobbled. He had a deft hand with tools, he could easily have fixed them, but there were always so many things to fix, and there was not time enough to go round. He went into the kitchen, where he had carpentered under a succession of cooks, went up to the bathroom on the second floor, where there was only a painted tin tub; the taps were so old that no plumber could ever screw them tight enough to stop the drip, the window could only be coaxed up and down by wriggling, and the doors of the linen closet didn't fit. He had sympathized with his daughters' dissatisfaction, though he could never quite agree with them that the bath should be the most attractive room in the house. He had spent the happiest years of his youth in a house at Versailles where it distinctly was not, and he had known many charming people who had no bath at all. However, as his wife said: "If your country has contributed one thing, at least, to civilization, why not have it?" Many a night, after blowing out his study lamp, he had leaped into that tub, clad in his pyjamas, to give it another coat of some one of the many paints that were advertised to behave like porcelain, and didn't.

The Professor in pyjamas was not an unpleasant sight; for looks, the fewer clothes he had on, the better. Anything that clung to his body showed it to be built upon extremely good bones, with the slender hips and springy shoulders of a tireless swimmer. Though he was born on Lake Michigan, of mixed stock (Canadian French on one side, and American farmers on the other), St. Peter was commonly said to look like a Spaniard. That was possibly because he had been in Spain a good deal, and was an authority on certain phases of Spanish history. He had a long brown face, with an oval chin over which he wore a close-trimmed Van Dyke, like a tuft of shiny black fur. With this silky, very black hair, he had a tawny skin with gold lights in it, a hawk nose, and hawk-like eyes—brown and gold and green. They were set in ample cavities, with plenty of room to move about, under thick, curly, black eyebrows that turned up sharply at the outer ends, like military moustaches. His wicked-looking eyebrows made his students call him Mephistopheles—and there was no evading the searching eyes underneath them; eyes that in a flash could pick out a friend or an unusual stranger from a throng. They had lost none of their fire, though just now the man behind them was feeling a diminution of ardour.

His daughter Kathleen, who had done several successful studies of him in water-colour, had once said:— "The thing that really makes Papa handsome is the modelling of his head between the top of his ear and his crown; it is quite the best thing about him." That part of his head was high, polished, hard as bronze, and the close-growing black hair threw off a streak of light along the rounded ridge where the skull was fullest. The mould of his head on the side was so individual and definite, so far from casual, that it was more like a statue's head than a man's.

From one of the dismantled windows the Professor happened to look out into his back garden, and at that cheerful sight he went quickly downstairs and escaped from the dusty air and brutal light of the empty rooms.

His walled-in garden had been the comfort of his life—and it was the one thing his neighbours held against him. He started to make it soon after the birth of his first daughter, when his wife began to be unreasonable about his spending so much time at the lake and on the tennis court. In this undertaking he got help and encouragement from his landlord, a retired German farmer, good-natured and lenient about everything but spending money. If the Professor happened to have a new baby at home, or a faculty dinner, or an illness in the family, or any unusual expense, Appelhoff cheerfully waited for the rent; but pay for repairs he would not. When it was a question of the garden, however, the old man sometimes stretched a point. He helped his tenant with seeds and slips and sound advice, and with his twisted old back. He even spent a little money to bear half the expense of the stucco wall.

The Professor had succeeded in making a French garden in Hamilton. There was not a blade of grass; it was a tidy half-acre of glistening gravel and glistening shrubs and bright flowers. There were trees, of course; a spreading horse-chestnut, a row of slender Lombardy poplars at the back, along the white wall, and in the middle two symmetrical, round-topped linden-trees. Masses of green-brier grew in the corners, the prickly stems interwoven and clipped until they were like great bushes. There was a bed for salad herbs. Salmon-pink geraniums dripped over the wall. The French marigolds and dahlias were just now at their best—such dahlias as no one else in Hamilton could grow. St. Peter had tended this bit of ground for over twenty years, and had got the upper hand of it. In the spring, when home sickness for other lands and the fret of things unaccomplished awoke, he worked off his discontent here. In the long hot summers, when he could not go abroad, he stayed at home with his garden, sending his wife and daughters to Colorado to escape the humid prairie heat, so nourishing to wheat and corn, so exhausting to human beings. In those months when he was a bachelor again, he brought down his books and papers and worked in a deck chair under the linden-trees; break-fasted and lunched and had his tea in the garden. And it was there he and Tom Outland used to sit and talk half through the warm, soft nights.

On this September morning, however, St. Peter knew that he could not evade the unpleasant effects of change by tarrying among his autumn flowers. He must plunge in like a man, and get used to the feeling that under his work-room there was a dead, empty house. He broke off a geranium blossom, and with it still in his hand went resolutely up two flights of stairs to the third floor where, under the slope of the mansard roof, there was one room still furnished—that is, if it had ever been furnished.

The low ceiling sloped down on three sides, the slant being interrupted on the east by a single square window, swinging outward on hinges and held ajar by a hook in the sill. This was the sole opening for light and air. Walls and ceiling alike were covered with a yellow paper which had once been very ugly, but had faded into inoffensive neutrality. The matting on the floor was worn and scratchy. Against the wall stood an old walnut table, with one leaf up, holding piles of orderly papers. Before it was a cane-backed office chair that turned on a screw. This dark den had for many years been the Professor's study.

Downstairs, off the back parlour, he had a show study, with roomy shelves where his library was housed, and a proper desk at which he wrote letters. But it was a sham. This was the place where he worked. And not he alone. For three weeks in the fall, and again three in the spring, he shared his cuddy with Augusta, the sewing-woman, niece of his old landlord, a reliable, methodical spinster, a German Catholic and very devout.

Since Augusta finished her day's work at five o'clock, and the Professor, on week-days, worked here only at night, they did not elbow each other too much. Besides, neither was devoid of consideration. Every evening, before she left, Augusta swept up the scraps from the floor, rolled her patterns, closed the sewing-machine, and picked ravellings off the box-couch, so that there would be no threads to stick to the Professor's old smoking-jacket if he should happen to lie down for a moment in working-hours.

St. Peter, in his turn, when he put out his lamp after midnight, was careful to brush away ashes and tobacco crumbs—smoking was very distasteful to Augusta— and to open the hinged window back as far as it would go, on the second hook, so that the night wind might carry away the smell of his pipe as much as possible. The unfinished dresses which she left hanging on the forms, however, were often so saturated with smoke that he knew she found it a trial to work on them next morning.

These "forms" were the subject of much banter between them. The one which Augusta called "the bust" stood in the darkest corner of the room, upon a high wooden chest in which blankets and winter wraps were yearly stored. It was a headless, armless female torso, covered with strong black cotton, and so richly developed in the part for which it was named that the Professor once explained to Augusta how, in calling it so, she followed a natural law of language, termed, for convenience, metonymy. Augusta enjoyed the Professor when he was risqué, since she was sure of his ultimate delicacy. Though this figure looked so ample and billowy (as if you might lay your head upon its deep-breathing softness and rest safe forever), if you touched it you suffered a severe shock, no matter how many times you had touched it before. It presented the most unsympathetic surface imaginable. Its hardness was not that of wood, which responds to concussion with living vibration and is stimulating to the hand, nor that of felt, which drinks something from the fingers. It was a dead, opaque, lumpy solidity, like chunks of putty, or tightly packed sawdust—very disappointing to the tactile sense, yet somehow always fooling you again. For no matter how often you had bumped up against that torso, you could never believe that contact with it would be as bad as it was.

The second form was more self-revelatory; a full-length female figure in a smart wire skirt with a trim metal waist line. It had no legs, as one could see all too well, no viscera behind its glistening ribs, and its bosom resembled a strong wire bird-cage. But St. Peter contended that it had a nervous system. When Augusta left it clad for the night in a new party dress for Rosamond or Kathleen, it often took on a sprightly, tricky air, as if it were going out for the evening to make a great show of being harum-scarum, giddy, folle. It seemed just on the point of tripping downstairs, or on tiptoe, waiting for the waltz to begin. At times the wire lady was most convincing in her pose as a woman of light behaviour, but she never fooled St. Peter. He had his blind spots, but he had never been taken in by one of her kind!

Augusta had somehow got it into her head that these forms were unsuitable companions for one engaged in scholarly pursuits, and she periodically apologized for their presence when she came to install herself and fulfil her "time" at the house.

"Not at all, Augusta," the Professor had often said. "If they were good enough for Monsieur Bergeret, they are certainly good enough for me.

This morning, as St. Peter was sitting in his desk chair, looking musingly at the pile of papers before him, the door opened and there stood Augusta herself. How astonishing that he had not heard her heavy, deliberate tread on the now uncarpeted stair!

"Why, Professor St. Peter! I never thought of finding you here, or I'd have knocked. I guess we will have to do our moving together."

St. Peter had risen—Augusta loved his manners—but he offered her the sewing-machine chair and resumed his seat.

"Sit down, Augusta, and we'll talk it over. I'm not moving just yet—don't want to disturb all my papers. I'm staying on until I finish a piece of writing. I've seen your uncle about it. I'll work here, and board at the new house. But this is confidential. If it were noised about, people might begin to say that Mrs. St. Peter and I had—how do they put it, parted, separated?"

Augusta dropped her eyes in an indulgent smile. "I think people in your station would say separated." "Exactly; a good scientific term, too. Well, we haven't, you know. But I'm going to write on here for a while.

"Very well, sir. And I won't always be getting in your way now. In the new house you have a beautiful study downstairs, and I have a light, airy room on the third floor."

"Where you won't smell smoke, eh?"

"Oh, Professor, I never really minded!" Augusta spoke with feeling. She rose and took up the black bust in her long arms.

The Professor also rose, very quickly. "What are you doing?"

She laughed. "Oh, I'm not going to carry them through the street, Professor! The grocery boy is downstairs with his cart, to wheel them over."

"Wheel them over?"

"Why, yes, to the new house, Professor. I've come a week before my regular time, to make curtains and hem linen for Mrs. St. Peter. I'll take everything over this morning except the sewing-machine— that's too heavy for the cart, so the boy will come back for it with the delivery wagon. Would you just open the door for me, please?"

"No, I won't! Not at all. You don't need her to make curtains. I can't have this room changed if I'm going to work here. He can take the sewing-machine—yes. But put her back on the chest where she belongs, please. She does very well there." St. Peter had got to the door, and stood with his back against it.

Augusta rested her burden on the edge of the chest.

"But next week I'll be working on Mrs. St. Peter's clothes, and I'll need the forms. As the boy's here, he'll just wheel them over," she said soothingly.

"I'm damned if he will! They shan't be wheeled. They stay right there in their own place. You shan't take away my ladies. I never heard of such a thing!"

Augusta was vexed with him now, and a little ashamed of him. "But, Professor, I can't work without my forms. They've been in your way all these years, and you've always complained of them, so don't be contrary, sir."

"I never complained, Augusta. Perhaps of certain disappointments they recalled, or of cruel biological necessities they imply—but of them individually, never! Go and buy some new ones for your airy atelier, as many as you wish—I'm said to be rich now, am I not?—Go buy, but you can't have my women. That's final."

Augusta looked down her nose as she did at church when the dark sins were mentioned. "Professor." she said severely, "I think this time you are carrying a joke too far. You never used to." From the tilt of her chin he saw that she felt the presence of some improper suggestion.

"No matter what you think, you can't have them. They considered, both were in earnest now. Augusta was first to break the defiant silence.

"I suppose I am to be allowed to take my patterns?"

"Your patterns? Oh, yes, the cut-out things you keep in the couch with my old note-books? Certainly, you can have them. Let me lift it for you." He raised the hinged top of the box-couch that stood against the wall, under the slope of the ceiling. At one end of the up-holstered box were piles of note-books and bundles of manuscript tied up in square packages with mason's cord. At the other end were many little rolls of patterns, cut out of newspapers and tied with bits of ribbon, gingham, silk, georgette; notched charts which followed the changing stature and figures of the Misses St. Peter from early childhood to womanhood. In the middle of the box, patterns and manuscripts interpenetrated.

"I see we shall have some difficulty in separating our life work, Augusta. We've kept our papers together a long while now.'

"Yes, Professor. When I first came to sew for Mrs. St. Peter, I never thought I should grow grey in her service."

He started. What other future could Augusta possibly have expected? This disclosure amazed him.,

"Well, well, we mustn't think mournfully of it, Augusta. Life doesn't turn out for any of us as we plan." He stood and watched her large slow hands travel about among the little packets, as she put them into his waste-basket to carry them down to the cart. He had often wondered how she managed to sew with hands that folded and unfolded as rigidly as umbrellas—no light French touch about Augusta; when she sewed on a bow, it stayed there. She herself was tall, large-boned, flat and stiff, with a plain, solid face, and brown eyes not destitute of fun. As she knelt by the couch, sorting her patterns, he stood beside her, his hand on the lid, though it would have stayed up unsupported. Her last remark had troubled him.

"What a fine lot of hair you have, Augusta! You know I think it's rather nice, that grey wave on each side. Gives it character. You'll never need any of this false hair that's in all the shop windows."

"There's altogether too much of that, Professor. So many of my customers are using it now—ladies you wouldn't expect would. They say most of it was cut off the heads of dead Chinamen. Really, it's got to be such a frequent thing that the priest spoke against it only last Sunday.

"Did he, indeed? Why, what could he say? Seems such a personal matter."

"Well, he said it was getting to be a scandal in the Church, and a priest couldn't go to see a pious woman any more without finding switches and rats and transformations lying about her room, and it was disgusting.

"Goodness gracious, Augusta! What business has a priest going to see a woman in the room where she takes off these ornaments—or to see her without them?"

Augusta grew red, and tried to look angry, but her laugh narrowly missed being a giggle. "He goes to give them the Sacrament, of course, Professor! You've made up your mind to be contrary today, haven't you?"

"You relieve me greatly. Yes, I suppose in cases of sudden illness the hair would be lying about where it was lightly taken off. But as you first quoted the priest, Augusta, it was rather shocking. You'll never convert me back to the religion of my fathers now, if you're going to sew in the new house and I'm going to work on here. Who is ever to remind me when it's All Souls' day, or Ember day, or Maundy Thursday, or anything?"

Augusta said she must be leaving. St. Peter heard her well-known tread as she descended the stairs. How much she reminded him of, to be sure! She had been most at the house in the days when his daughters were little girls and needed so many clean frocks. It was in those very years that he was beginning his great work; when the desire to do it and the difficulties attending such a project strove together in his mind like Macbeth's two spent swimmers—years when he had the courage to say to himself: "I will do this dazzling, this beautiful, this utterly impossible thing!"

During the fifteen years he had been working on his Spanish Adventurers in North America, this room had been his centre of operations. There had been delightful excursions and digressions; the two Sabbatical years when he was in Spain studying records, two summers in the South-west on the trail of his adventurers, another in Old Mexico, dashes to France to see his foster-brothers. But the notes and the records and the ideas always came back to this room. It was here they were digested and sorted, and woven into their proper place in his history.

Fairly considered, the sewing-room was the most inconvenient study a man could possibly have, but it was the one place in the house where he could get isolation, insulation from the engaging drama of domestic life. No one was tramping over him, and only a vague sense, generally pleasant, of what went on below came up the narrow stairway. There were certainly no other advantages. The furnace heat did not reach the third floor. There was no way to warm the sewing-room, except by a rusty, round gas stove with no flue—a stove which consumed gas imperfectly and contaminated the air. To remedy this, the window must be left open—otherwise, with the ceiling so low, the air would speedily become unfit to breathe. If the stove were turned down, and the window left open a little way, a sudden gust of wind would blow the wretched thing out altogether, and a deeply absorbed man might be asphyxiated before he knew it. The Professor had found that the best method, in winter, was to turn the gas on full and keep the window wide on the hook, even if he had to put on a leather jacket over his working-coat. By that arrangement he had somehow managed to get air enough to work by.

He wondered now why he had never looked about for a better stove, a newer model; or why he had not at least painted this one, flaky with rust. But he had been able to get on only by neglecting negative comforts. He was by no means an ascetic. He knew that he was terribly selfish about personal pleasures, fought for them. If a thing gave him delight, he got it, if he sold his shirt for it. By doing without many so-called necessities he had managed to have his luxuries. He might, for instance, have had a convenient electric drop-light attached to the socket above his writing-table. Preferably he wrote by a faithful kerosene lamp which he filled and tended himself. But sometimes he found that the oil-can in the closet was empty; then, to get more, he would have had to go down through the house to the cellar, and on his way he would almost surely become interested in what the children were doing, or in what his wife was doing—or he would notice that the kitchen linoleum was breaking under the sink where the maid kicked it up, and he would stop to tack it down. On that perilous journey down through the human house he might lose his mood, his enthusiasm, even his temper. So when the lamp was empty—and that usually occurred when he was in the middle of a most important passage—he jammed an eyeshade on his forehead and worked by the glare of that tormenting pear-shaped bulb, sticking out of the wall on a short curved neck just about four feet above his table. It was hard on eyes even as good as his. But once at his desk, he didn't dare quit it. He had found that you can train the mind to be active at a fixed time, just as the stomach is trained to be hungry at certain hours of the day.

If someone in the family happened to be sick, he didn't go to his study at all. Two evenings of the week he spent with his wife and daughters, and one evening he and his wife went out to dinner, or to the theatre or a concert. That left him only four. He had Saturdays and Sundays, of course, and on those two days he worked like a miner under a landslide. Augusta was not allowed to come on Saturday, though she was paid for that day. All the while that he was working so fiercely by night, he was earning his living during the day; carrying full university work and feeding himself out to hundreds of students in lectures and consultations. But that was another life.

St. Peter had managed for years to live two lives, both of them very intense. He would willingly have cut down on his university work, would willingly have given his students chaff and sawdust—many instructors had nothing else to give them and got on very well—but his misfortune was that he loved youth—he was weak to it, it kindled him. If there was one eager eye, one doubting, critical mind, one lively curiosity in a whole lecture room full of commonplace boys and girls, he was its servant. That ardour could command him. It hadn't worn out with years, this responsiveness, any more than the magnetic currents wear out; it had nothing to do with Time.

But he had burned his candle at both ends to some purpose—he had got what he wanted. By many petty economies of purse, he had managed to be extravagant with not a cent in the world but his professor's salary—he didn't, of course, touch his wife's small income from her father. By eliminations and combinations so many and subtle that it now made his head ache to think of them, he had done full justice to his university lectures, and at the same time carried on an engrossing piece of creative work. A man can do anything if he wishes to enough, St. Peter believed. Desire is creation, is the magical element in that process. If there were an instrument by which to measure desire, one could foretell achievement. He had been able to measure it, roughly, just once, in his student Tom Outland,—and he had foretold.

There was one fine thing about this room that had been the scene of so many defeats and triumphs. From the window he could see, far away, just on the horizon, a long, blue, hazy smear—Lake Michigan, the inland sea of his childhood. Whenever he was tired and dull, when the white pages before him remained blank or were full of scratched-out sentences, then he left his desk. took the train to a little station twelve miles away, and spent a day on the lake with his sail-boat; jumping out to swim, floating on his back alongside, then climbing into his boat again.

When he remembered his childhood, he remembered blue water. There were certain human figures against it, of course; his practical, strong-willed Methodist mother, his gentle, weaned-away Catholic father, the old Kanuck grandfather, various brothers and sisters. But the great fact in life, the always possible escape from dullness, was the lake. The sun rose out of it, the day began there; it was like an open door that nobody could shut. The land and all its dreariness could never close in on you. You had only to look at the lake, and you knew you would soon be free. It was the first thing one saw in the morning, across the rugged cow pasture studded with shaggy pines, and it ran through the days like the weather, not a thing thought about, but a part of consciousness itself. When the ice chunks came in of a winter morning, crumbly and white, throwing off gold and rose-coloured reflections from a copper-coloured sun behind the grey clouds, he didn't observe the detail or know what it was that made him happy; but now, forty years later, he could recall all its aspects perfectly. They had made pictures in him when he was unwilling and unconscious, when his eyes were merely open wide.

When he was eight years old, his parents sold the lakeside farm and dragged him and his brothers and sisters out to the wheat lands of central Kansas. St. Peter nearly died of it. Never could he forget the few moments on the train when that sudden, innocent blue across the sand dunes was dying for ever from his sight. It was like sinking for the third time. No later anguish, and he had had his share, went so deep or seemed so final. Even in his long, happy student years with the Thierault family in France, that stretch of blue water was the one thing he was homesick for. In the summer he used to go with the Thierault boys to Brittany or to the Languedoc coast; but his lake was itself, as the Channel and the Mediterranean were themselves. "No," he used to tell the boys, who were always asking him about le Michigan, "it is altogether different. It is a sea, and yet it is not salt. It is blue, but quite another blue. Yes, there are clouds and mists and sea-gulls, but—I don't know, il est toujours plus naif."

Afterward, when St. Peter was looking for a professorship, because he was very much in love and must marry at once, out of the several positions offered him he took the one at Hamilton, not because it was the best, but because it seemed to him that any place near the lake was a place where one could live. The sight of it from his study window these many years had been of more assistance than all the convenient things he had done without would have been.

Just in that corner, under Augusta's archaic "forms, he had always meant to put the filing-cabinets he had never spared the time or money to buy. They would have held all his notes and pamphlets, and the spasmodic rough drafts of passages far ahead. But he had never got them, and now he really didn't need them: it would be like locking the stable after the horse is stolen. For the horse was gone —that was the thing he was feeling most just now. In spite of all he'd neglected, he had completed his Spanish Adventurers in eight volumes—without filing-cabinets or money or a decent study or a decent stove—and without encouragement, Heaven knew! For all the interest the first three volumes awoke in the world, he might as well have dropped them into Lake Michigan. They had been timidly reviewed by other professors of history, in technical and educational journals. Nobody saw that he was trying to do something quite different—they merely thought he was trying to do the usual thing, and had not succeeded very well. They recommended to him the more even and genial style of John Fiske.

St. Peter hadn't, he could honestly say, cared a whoop—not in those golden days. When the whole plan of his narrative was coming clearer and clearer all the time, when he could feel his hand growing easier with his material, when all the foolish conventions about that kind of writing were falling away and his relation with his work was becoming every day more simple, natural, and happy,— he cared as little as the Spanish Adventurers themselves what Professor So-and-So thought about them. With the fourth volume he began to be aware that a few young men, scattered about the United States and England, were intensely interested in his experiment. With the fifth and sixth, they began to express their interest in lectures and in print. The two last volumes brought him a certain international reputation and what were called rewards—among them, the Oxford prize for history, with its five thousand pounds, which had built him the new house into which he did not want to move.

"Godfrey." his wife had gravely said one day, when she detected an ironical turn in some remark he made about the new house, "is there something you would rather have done with that money than to have built a house with it?"

"Nothing, my dear, nothing. If with that cheque I could have bought back the fun I had writing my history, you'd never have got your house. But one couldn't get that for twenty thousand dollars. The great pleasures don't come so cheap. There is nothing else, thank you.

2

That evening St. Peter was in the new house, dressing for dinner. His two daughters and their husbands were dining with them, also an English visitor. Mrs. St. Peter heard the shower going as she passed his door. She entered his room and waited until he came out in his bath-robe, rubbing his wet, ink-black hair with a towel.

"Surely you'll admit that you like having your own bath," she said, looking past him into the glittering white cubicle, flooded with electric light, which he had just quitted.

"Whoever said I didn't? But more than anything else, I like my closets. I like having room for all my clothes, without hanging one coat on top of another, and not having to get down on my marrow-bones and fumble in dark corners to find my shoes."

"Of course you do. And it's much more dignified, at your age, to have a room of your own. "It's convenient, certainly, though I hope I'm not so old as to be personally repulsive?" He glanced into the mirror and straightened his shoulders as if he were trying on a coat.

Mrs. St. Peter laughed,—a pleasant, easy laugh with genuine amusement in it. "No, you are very handsome, my dear, especially in your bath-robe. You grow better-looking and more intolerant all the time. "Intolerant?" He put down his shoe and looked up at her. The thing that stuck in his mind constantly was that she was growing more and more intolerant, about everything except her sons-in-law; that she would probably continue to do so, and that he must school himself to bear it.

"I suppose it's a natural process," she went on, "but you ought to try, try seriously, I mean, to curb it where it affects the happiness of your daughters. You are too severe with Scott and Louie. All young men have foolish vanities—you had plenty."

St. Peter sat with his elbows on his knees, leaning forward and playing absently with the tassels of his bath-robe. "Why, Lillian, I have exercised the virtue of patience with those two young men more than with all the thousands of young ruffians who have gone through my classrooms. My forbearance is overstrained, it's gone flat. That's what's the matter with me. "Oh, Godfrey, how can you be such a poor judge of your own behaviour? But we won't argue about it now. You'll put on your dinner coat? And do try to be sympathetic and agreeable tonight.

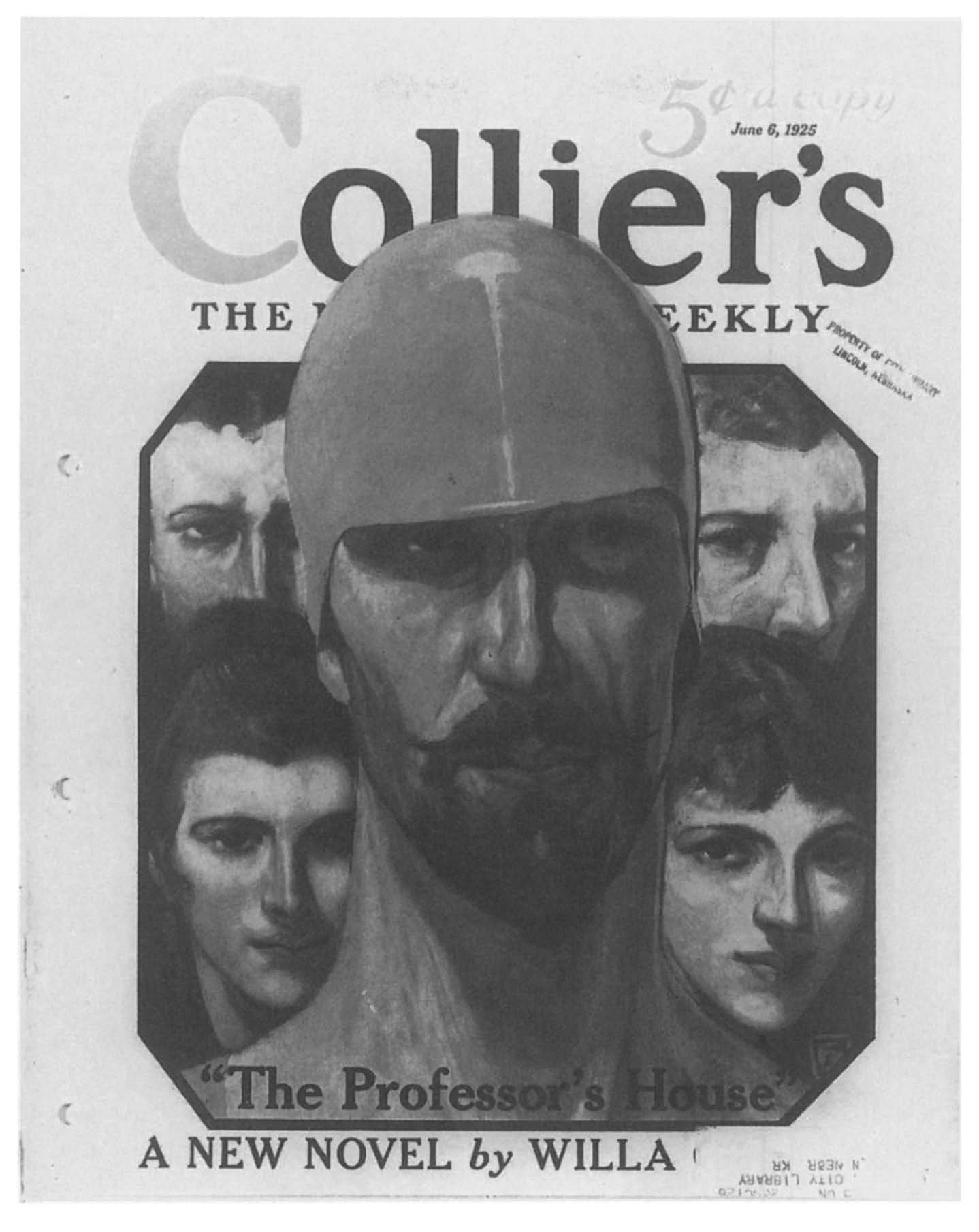

Half an hour later Mr. and Mrs. Scott McGregor and Mr. and Mrs. Louie Marsellus arrived, and soon after them the English scholar, Sir Edgar Spilling, so anxious to do the usual thing in America that he wore a morning street suit. He was a gaunt, rugged, large-boned man of fifty, with long legs and arms, a pear-shaped face, and a drooping, pre-war moustache. His specialty was Spanish history, and he had come all the way to Hamilton, from his cousin's place in Saskatchewan, to enquire about some of Doctor St. Peter's "sources. Introductions over, it was the Professor's son-in-law, Louie Marsellus, who took Sir Edgar in hand. He remembered having met in China a Walter Spilling, who was, it turned out, a brother of Sir Edgar. Marsellus had also a brother there, engaged in the silk trade. They exchanged opinions on conditions in the Orient, while young McGregor put on his horn-rimmed spectacles and roamed restlessly up and down the library. The two daughters sat near their mother, listening to the talk about China.

Mrs. St. Peter was very fair, pink and gold,—a pale gold, now that she was becoming a little grey. The tints of her face and hair and lashes were so soft that one did not realize, on first meeting her, how very definitely and decidedly her features were cut, under the smiling infusion of colour. When she was annoyed or tired, the lines became severe. Rosamond, the elder daughter, resembled her mother in feature, though her face was heavier. Her colouring was altogether different; dusky black hair, deep dark eyes, a soft white skin with rich brunette red in her cheeks and lips. Nearly everyone considered Rosamond brilliantly beautiful. Her father, though he was very proud of her, demurred from the general opinion. He thought her too tall, with a rather awkward carriage. She stooped a trifle, and was wide in the hips and shoulders. She had, he sometimes remarked to her mother, exactly the wide femur and flat shoulder-blade of his old slab-sided Kanuck grandfather. For a tree. hewer they were an asset. But St. Peter was very critical. Most people saw only Rosamond's smooth black head and white throat, and the red of her curved lips that was like the duskiness of dark, heavy-scented roses.

Kathleen, the younger daughter, looked even younger than she was— had the slender, undeveloped figure then very much in vogue. She was pale, with light hazel eyes, and her hair was hazel-coloured with distinctly green glints in it. To her father there was something very charming in the curious shadows her wide cheekbones cast over her cheeks, and in the spirited tilt of her head. Her figure in profile, he used to tell her, looked just like an interrogation point.

Mrs. St. Peter frankly liked having a son-in-law who could tot up acquaintances with Sir Edgar from to Alaska. Scott, she saw, was going to be sulky because Sir Edgar and Marsellus were talking about things beyond his little circle of interests. She made no effort to draw him into the conversation, but let him prowl like a restless leopard among the books. The Professor was amiable, but quiet. When the second maid came to the door and signalled that dinner was ready—dinner was signaled, not announced—Mrs. St. Peter took Sir Edgar and guided him to his seat at her right, while the others found their usual places. After they had finished the soup, she had some difficulty in summoning the little maid to take away the plates, and explained to her guest that the electric bell, under the table, wasn't connected as yet—they had been in the new house less than a week, and the trials of building were not over.

"Oh? Then if I had happened along a fortnight ago I shouldn't have found you here? But it must be very interesting, building your own house and arranging it as you like," he responded.

Marsellus, silenced during the soup, came in with a warm smile and a slight shrug of the shoulders. "Building is the word with us, Sir Edgar, my—oh, isn't it! My wife and I are in the throes of it. We are building a country house, rather an ambitious affair, out on the wooded shores of Lake Michigan. Perhaps you would like to run out in my car and see it? What are your engagements for tomorrow? I can take you out in half an hour, and we can lunch at the Country Club. We have a magnificent site; primeval forest behind us and the lake in front, with our own beach—my father-in- law, you must know, is a formidable swimmer. We've been singularly fortunate in our architect,—a young Norwegian, trained in Paris. He's doing us a Norwegian manor house, very harmonious with its setting, just the right thing for rugged pine woods and high headlands."

Sir Edgar seemed most willing to make this excursion, and allowed Marsellus to fix an hour, greatly to the surprise of McGregor, whose look at his wife implied that he entertained serious doubts whether this baronet with walrus moustaches amounted to much after all.

The engagement made, Louie turned to Mrs. St. Peter. "And won't you come too, Dearest? You haven't been out since we got our wonderful wrought-iron door fittings from Chicago. We found just the right sort of hinge and latch, Sir Edgar, and had all the others copied from it. None of your Colonial glass knobs for us!"

Mrs. St. Peter sighed. Scott and Kathleen had just glass-knobbed their new bungalow throughout, yet she knew Louie didn't mean to hurt their feelings—it was his heedless enthusiasm that made him often say untactful things.

"We've been extremely fortunate in getting all the little things right," Louie was gladly confiding to Sir Edgar. "There's really not a flaw in the conception. I can say that, because I'm a mere onlooker, the whole thing's been done by the Norwegian and my wife and Mrs. St. Peter. And," he put his hand down affectionately upon Mrs. St. Peter's bare arm, "and we've named our place! I've already ordered the house stationery. No, Rosamond, I won't keep our little secret any longer. It will please your father, as well as your mother. We call our place 'Outland, Sir Edgar."

He dropped the announcement and drew back. His mother-in-law rose to it—Spilling could scarcely be expected to understand.

"How splendid, Louie! A real inspiration."

"Yes, isn't it? I knew that would go to your hearts. The Professor had expressed his emotion only by lifting his heavy, sharply uptwisted eyebrows. "Let me explain, Sir Edgar," Marsellus went on eagerly. "We have named our place for Tom Outland, a brilliant young American scientist and inventor, who was killed in Flanders, fighting with the Foreign Legion, the second year of the war, when he was barely thirty years of age. Before he dashed off to the front, this youngster had discovered the principle of the Outland vacuum, worked out the construction of the Outland engine that is revolutionizing aviation. He had not only invented it, but, curiously enough for such a hot-headed fellow, had taken pains to protect it. He had no time to communicate his discovery or to commercialize it—simply bolted to the front and left the most important discovery of his time to take care of itself."

Sir Edgar, fork arrested, looked a trifle dazed. "Am I to understand that you are referring to the inventor of the Outland engine?"

Louie was delighted. "Exactly that! Of course you would know all about it. My wife was young Outland's fiancée—is virtually his widow. Before he went to France he made a will in her favour; he had no living relatives, indeed. Toward the close of the war we began to sense the importance of what Outland had been doing in his laboratory—I am an electrical engineer by profession. We called in the assistance of experts and got the idea over from the laboratory to the trade. The monetary returns have been and are, of course, large.

While Louie paused long enough to have some inter- course with the roast before it was taken away, Sir Edgar remarked that he himself had been in the Air Service during the war, in the construction department, and that it was most extraordinary to come thus bi chance upon the genesis of the Outland engine.

"You see," Louie told him, "Outland got nothing out of it but death and glory. Naturally, we feel terribly indebted. We feel it's our first duty in life to use that money as he would have wished—we've endowed scholarships in his own university here, and that sort of thing. But our house we want to have as a sort of memo. rial to him. We are going to transfer his laboratory there, if the university will permit,—all the apparatus he worked with. We have a room for his library and pictures. When his brother scientists come to Hamilton to look him up, to get information about him, as they are doing now already, at Outland they will find his books and instruments, all the sources of his inspiration."

"Even Rosamond," murmured McGregor, his eyes upon his cool green salad. He was struggling with a desire to shout to the Britisher that Marsellus had never so much as seen Tom Outland, while he, McGregor, had been his classmate and friend.

Sir Edgar was as much interested as he was mystified. He had come here to talk about manuscripts shut up in certain mouldering monasteries in Spain, but he had almost forgotten them in the turn the conversation had taken. He was genuinely interested in aviation and all its problems. He asked few questions, and his comments were almost entirely limited to the single exclamation, "Oh!" But this, from his lips, could mean a great many things; indifference, sharp interrogation, sympathetic interest, the nervousness of a modest man on hearing disclosures of a delicately personal nature. McGregor, before the others had finished dessert, drew a big cigar from his pocket and lit it at one of the table candles, as the horridest thing he could think of to do.

When they left the dining-room, St. Peter, who had scarcely spoken during dinner, took Sir Edgar's arm and said to his wife: "If you will excuse us, my dear, we have some technical matters to discuss." Leading his guest into the library, he shut the door.

Marsellus looked distinctly disappointed. He stood gazing wistfully after them, like a little boy told to go to bed. Louie's eyes were vividly blue, like hot sapphires, but the rest of his face had little colour—he was a rather mackerel-tinted man. Only his eyes, and his quick, impetuous movements, gave out the zest for life with which he was always bubbling. There was nothing Semitic about his countenance except his nose—that took the lead. It was not at all an unpleasing feature, but it grew out of his face with masterful strength, well-rooted, like a vigorous oak-tree growing out of a hill-side.

Mrs. St. Peter, always concerned for Louie, asked him to come and look at the new rug in her bedroom. This revived him; he took her arm, and they went upstairs together.

McGregor was left with the two sisters. "Outland. outlandish!" he muttered, while he fumbled about for an ash-tray. Rosamond pretended not to hear him, but the dusky red on her cheeks crept a little farther toward her ears.

"Remember, we are leaving early, Scott," said Kathleen. "You have to finish your editorial to-night.

"Surely you don't make him work at night, too?" Rosamond asked. "Doesn't he have to rest his brain sometimes? Humour is always better if it's spontaneous."

"Oh, that's the trouble with me." Scott assured her. "Unless I keep my nose to the grindstone, I'm too damned spontaneous and tell the truth, and the public won't stand for it. It's not an editorial I have to finish, it's the daily prose poem I do for the syndicate, for which I get twenty-five beans. This is the motif:

'When your pocket is under-moneyed and your fancy is over-girled, you'll have to admit while you're cursing it, it's a mighty darned good old world.'

Bang, bang!"

He threw his cigar-end savagely into the fire-place. He knew that Rosamond detested his editorials and his jingles. She had fastidious taste in literature, like her mother—though he didn't think she had half the general intelligence of his wife. She also, now that she was Tom Outland' heir, detested to hear sums of money mentioned, especially small sums.

After the good-nights were said, and they were out-side the front door, McGregor seized his wife's elbow and rushed her down the walk to the gate where his Ford was parked, breaking out in her ear as they ran: "Now what the hell is a virtual widow? Does he mean a Virtuous widow, or the reverseous: Bang, bang!

St. Peter awoke the next morning with the wish that he could be transported on his mattress from the new house to the old. But it was Sunday, and on that day his wife always breakfasted with him. There was no way out; they would meet at compt.

When he reached the dining-room Lillian was already at the table, behind the percolator. "Good morning, Godfrey. I hope you had a good night." Her tone just faintly implied that he hadn't deserved one.

"Excellent. And you?"

"I had a good conscience." She smiled ruefully at him. "How can you let yourself be ungracious in your own house?"

"Oh, dear! And I went to sleep happy in the belief that I hadn't said anything amiss the whole evening." "Nor anything aright, that I heard. Your disapproving silence can kill the life of any company."

"It didn't seem to, last night. You're entirely wrong about Marsellus. He doesn't notice."

"He's too polite to take notice, but he feels it. He's very sensitive, under a well-schooled impersonal manner.

St. Peter laughed. "Nonsense, Lillian! If he were, he couldn't pick up a dinner party and walk off with it, as he almost always does. I don't mind when it's our dinner, but I hate seeing him do it in other people's houses."

"Be fair, Godfrey. You know that if you'd once begun to talk about your work in Spain, Louie would have followed it up with enthusiasm. Nobody is prouder of you than he.

"That's why I kept quiet. Support can be too able—certainly too fluent.

"There you are; the dog in the manger! You won't let him discuss your affairs, and you are annoyed when he talks about his own.

"I admit I can't bear it when he talks about Outland as his affair. (I mean Tom, of course, not their con- founded place!) This calling it after him passes my comprehension. And Rosamond's standing for it! It's brazen impudence.

Mrs. St. Peter frowned pensively. "I knew you wouldn't like it, but they were so pleased about it, and their motives are so generous——"

"Hang it, Outland doesn't need their generosity! They've got everything he ought to have had, and the least they can do is to be quiet about it, and not convert his very bones into a personal asset. It all comes down to this, my dear: one likes the florid style, or one doesn't. You yourself used not to like it. And will you give me some more coffee, please?"

She refilled his cup and handed it across the table. "Nice hands," he murmured, looking critically at them as he took it, "always such nice hands."

"Thank you. I dislike floridity when it is beaten up to cover the lack of something, to take the place of some. thing. I never disliked it when it came from exuberance. Then it isn't floridness, it's merely strong colour.

"Very well; some people don't care for strong colour. It fatigues them." He folded his napkin. "Now I must be off to my desk."

"Not quite yet. You never have time to talk to me. Just when did it begin, Godfrey, in the history of manners—that convention that if a man were pleased with his wife or his house or his success, he shouldn't say so, frankly?" Mrs. St. Peter spoke thoughtfully, as if she had considered this matter before.

"Oh, it goes back a long way. I rather think it began in the Age of Chivalry—King Arthur's knights. Whoever it was lived in that time, some feeling grew up that a man should do fine deeds and not speak of them, and that he shouldn't speak the name of his lady, but sing of her as a Phyllis or a Nicolette. It's a nice idea, reserve about one's deepest feelings: keeps them fresh."

"The Oriental peoples didn't have an Age of Chivalry. They didn't need one," Lillian observed. "And this reserve—it becomes in itself ostentatious, a vain-glorious vanity."

"Oh, my dear, all is vanity! I don't dispute that. Now I must really go, and I wish I could play the game as well as you do. I have no enthusiasm for being a father-in-law. It's you who keep the ball rolling. I fully appreciate that.

"Perhaps," mused his wife, as he rose, "it's because you didn't get the son-in-law you wanted. And yet he was highly coloured, too."

The Professor made no reply to this. Lillian had been fiercely jealous of Tom Outland. As he left the house, he was reflecting that people who are intensely in love when they marry, and who go on being in love, always meet with something which suddenly or gradually makes a difference. Sometimes it is the children, or the grubbiness of being poor, sometimes a second infatuation. In their own case it had been, curiously enough, his pupil, Tom Outland.

St. Peter had met his wife in Paris, when he was but twenty-four, and studying for his doctorate. She too was studying there. French people thought her an English girl because of her gold hair and fair complexion. With her really radiant charm, she had a very interesting mind—but it was quite wrong to call it mind, the connotation was false. What she had was a richly endowed nature that responded strongly to life and art, and very vehement likes and dislikes which were often quite out of all proportion to the trivial object or person that aroused them. Before his marriage, and for years afterward, Lillian's prejudices, her divinations about people and art (always instinctive and unexplained, but nearly always right), were the most interesting things in St. Peter's life. When he accepted almost the first position offered him, in order to marry at once, and came to take the chair of European history at Hamilton, he was thrown upon his wife for mental companionship. Most of his colleagues were much older than he, but they were not his equals either in scholarship or in experience of the world. The only other man in the faculty who was carrying on important research work was Doctor Crane, the professor of physics. St. Peter saw a good deal of him, though outside his specialty he was uninteresting—a narrow-minded man, and painfully unattractive. Years ago Crane had begun to suffer from a malady which in time proved incurable, and which now sent him up for an operation periodically. St. Peter had had no friend in Hamilton of whom Lillian could possibly be jealous until Tom Outland came along, so well fitted by nature and early environment to help him with his work on the Spanish Adventurers.

When he had almost reached his old house and his study, the Professor remembered that he really must have an understanding with his landlord, or the place would be rented over his head. He turned and went down into another part of the city, by the car shops, where only workmen lived, and found his landlord's little toy house, set on a hill-side, over a basement faced up with red brick and covered with hop vines. Old Appelhoff was sitting on a bench before his door, making a broom. Raising broom corn was one of his economies. Beside him was his dachshund bitch, Minna.

St. Peter explained that he wanted to stay on in the empty house, and would pay the full rent each month. So irregular a project annoyed Appelhoff. "I like fine to oblige you, Professor, but dey is several parties looking at de house already, an' I don't like to lose a year's rent for maybe a few months."

"Oh, that's all right, Fred. I'll take it for the year, to simplify matters. I want to finish my new book before I move.

Fred still looked uneasy. "I better see de insurance man, ch? It says for purposes of domestic dwelling."

"He won't object. Let's have a look at your garden. What a fine crop of apples and sickle pears you have!"

"I don't like dem trees what don't bear noting," said the old man with sly humour, remembering the Professor's glistening, barren shrubs and the good ground wasted behind his stucco wall.

"How about your linden-trees?"

"Oh, dem Rowers is awful good for de headache!"

"You don't look as if you were subject to it, Fred."

"Not me, but my woman always had."

"Pretty lonesome without her, Appelhoff?"

"I miss her, Professor, but I ain't just lonesome." The old man rubbed his bristly chin. "My Minna here is most like a person, and den I got so many t'ings to t'ink about."

"Have you? Pleasant things, I hope?"

"Well, all kinds. When I was young, in de old country, I had it hard to git my wife at all, an' I never had time to 'ink. When I come to dis country I had to work so turrible hard on dat farm to make crops an' pay debts, dat I was like a horse. Now I have it easy, an' I take time to 'ink about all dem t'ings."

St. Peter laughed. "We all come to it, Appelhoff. That's one thing I'm renting your house for, to have room to think. Good morning."

Crossing the public park, on his way back to the old house, he espied his professional rival and enemy, Professor Horace Langtry, taking a Sunday morning stroll—very well got up in English clothes he had brought back from his customary summer in London, with a bowler hat of unusual block and a horn-handled walking-stick. In twenty years the two men had scarcely had speech with each other beyond a stiff "good morning." When Langtry first came to the university he looked hardly more than a boy, with curly brown hair and such a fresh complexion that the students called him Lily Langtry. His round pink cheeks and round eyes and round chin made him look rather like a baby grown big. All these years had made little difference, except that his curls were now quite grey, his rosy cheeks even rosier, and his mouth dropped a little at the corners, so that he looked like a baby suddenly grown old and rather cross about it.

Seeing St. Peter, the younger man turned abruptly into a side alley, but the Professor overtook him. "Good morning, Langtry. These elms are becoming real trees at last. They've changed a good deal since we first came here."

Doctor Langtry moved his rosy chin sidewise over his high double collar. "Good morning, Doctor St. Peter. I really don't remember much about the trees. They seem to be doing well now."

St. Peter stepped abreast of him. "There have been many changes, Langtry, and not all of them are good. Don't you notice a great difference in the student body as a whole, in the new crop that comes along every year now—how different they are from the ones of our early years here?

The smooth chin turned again, and the other professor of European history blinked. "In just what respect?" "Oh, in the all-embracing respect of quality! We have hosts of students, but they're a common sort."

"Perhaps. I can't say I've noticed it." The air between the two colleagues was not thawing out any. A church-bell rang. Langtry started hopefully. "You must excuse me, Doctor St. Peter, I am on my way to service."

The Professor gave it up with a shrug. "All right, all right, Langtry, as you will. Quelle folie!

Langtry half turned back, hesitated on the ball of his suddenly speeding foot, and said with faultless politeness: "I beg your pardon?"

St. Peter waved his hand with a gesture of negation, and detained the church-goer no longer. He sauntered along slackly through the hot September sunshine, wondering why Langtry didn't see the absurdity of their long grudge. They had always been directly opposed in matters of university policy, until it had almost become a part of their professional duties to outwit and cramp each other.

When young Langtry first came there, his specialty was supposed to be American history. His uncle was president of the board of regents, and very influential in State politics; the institution had to look to him, indeed, to get its financial appropriations passed by the Legislature. Langtry was a Tory in his point of view, and was considered very English in his tone and manner. His lectures were dull, and the students didn't like him. Every inducement was offered to make his courses popular. Liberal credits were given for collateral reading. A student could read almost anything that had ever been written in the United States and get credit for it in American history. He could charge up the time spent in perusing "The Scarlet Letter" to Colonial history, and "Tom Sawyer" to the Missouri Compromise, it was said. St. Peter openly criticized these lax methods, both to the faculty and to the regents. Naturally, "Madame Langtry" paid him out. During the Professor's second Sabbatical year in Spain, Horace and his uncle together very nearly got his department away from him. They worked so quietly that it was only at the eleventh hour that St. Peter's old students throughout the State got wind of what was going on, dropped their various businesses and professions for a few days, and came up to the capital in dozens and saved his place for him. The opposition had been so formidable that when it came time for his third year away, the Professor had not dared ask for it, but had taken an extension of his summer vacation instead. The fact that he was carrying on another line of work than his lectures, and was publishing books that weren't strictly text-books, had been used against him by Langtry' uncle.

As Langtry felt that the unpopularity of his course was due to his subject, a new chair was created for him. There couldn't be two heads in European history, so the board of regents made for him a chair of Renaissance history, or, as St. Peter said, a Renaissance chair of history. Of late years, for reasons that had not much to do with his lectures, Langtry had prospered better. To the new generations of country and village boys now pouring into the university in such large numbers, Langtry had become, in a curious way, an instructor in manners,—what is called an "influence." To the football-playing farmer boy who had a good allowance but didn't know how to dress or what to say, Langtry looked like a short cut. He had several times taken parties of undergraduates to London for the summer, and they had come back wonderfully brushed up. He introduced a very popular fraternity into the university, and its members looked after his interests, as did its affiliated sorority. His standing on the faculty was now quite as good as St. Peter's own, and the Professor wondered what Langtry still had to be sore about.

What was the use of keeping up the feud? They had both come there young men, fighting for their places and their lives; now they were not very young any more; they would neither of them, probably, ever hold a better position. Couldn't Langtry see it was a draw, that they had both been beaten?

On Monday afternoon St. Peter mounted to his study and lay down on the box-couch, tired out with his day at the university. The first few weeks of the year were very fatiguing for him; there were so many exhausting things besides his lectures and all the new students; long faculty meetings in which almost no one was ever frank, and always the old fight to keep up the standard of scholarship, to prevent the younger professors, who had a sharp eye to their own interests, from farming the whole institution out to athletics, and to the agricultural and commercial schools favoured and fostered by the State Legislature.

The September heat, too, was hard on him. He wanted to be out at the lake every day—it was never so fine as in late September. He was lying with closed eyes, resting his mind on the picture of intense autumn-blue water, when he heard a tap at the door and his daughter Rosamond entered, very handsome in a silk suit of a vivid shade of lilac, admirably suited to her complexion and showing that in the colour of her cheeks there was actually a tone of warm lavender. In that low room she seemed very tall indeed, a little out of drawing, as, to her father's eye, she so often did. Usually, however, people were aware only of her rich complexion, her curving, unresisting mouth and mysterious eyes. Tom Out- land had seen nothing else, and he was a young man who saw a great deal.

"Am I interrupting something important, Papa?"

"No, not at all, my dear. Sit down."

On his writing-table she caught a glimpse of pages in a handwriting not his—a script she knew very well.

"Not much choice of chairs, is there?" she smiled. "Papa, I don't like to have you working in a place like this. It's not fitting.

"Much easier than to break in a new room, Rosie. A work-room should be like an old shoe; no matter how shabby, it's better than a new one."

"That's really what I came to see you about." Rosamond traced the edge of a hole in the matting with the tip of her lilac sunshade. "Won't you let me build you a little study in the back yard of the new house? I have such good ideas for it, and you would have no bother about it at all."

"Oh, thank you, Rosamond. It's most awfully nice of you to think of it. But keep it just an idea—it's better so. Lots of things are. For the present I'll plod on here. It's absurd, but it suits me. Habit is such a big part of work."

"With Augusta's old things lying about, and those dusty old forms? Why didn't she at least get those out of your way?"

"Oh, they have a right here, by long tenure. It's their room, too. I don't want to come upon them lying in some dump-heap on the road to the lake. They remind me of the times when you were little girls, and your first party frocks used to hang on them at night, when worked."

Rosamond smiled, unconvinced. "Papa, don't joke with me. I've come to talk about something serious, and it's very difficult. You know I'm a little afraid of you." She dropped her shadowy, bewitching eyes.

"Afraid of me? Never!"

"Oh, yes, I am when you're sarcastic. You mustn't be today, please. Louie and I have often talked this over. We feel strongly about it. He's often been on the point of blurting out with it, but I've curbed him. You don't always approve of Louie and me. Of course it was only Louie's energy and technical knowledge that ever made Tom's discovery succeed commercially, but we don't feel that we ought to have all the returns from it. We think you ought to let us settle an income on you, so that you could give up your university work and devote all your time to writing and research. That is what Tom would have wanted."

St. Peter rose quickly, with the light, supple spring he had when he was very nervous, crossed to the window, wide on its hook, and half closed it. "My dear daughter," he said decisively, when he had turned round to her, "I couldn't possibly take any of Outland's money."

"But why not? You were the best friend he had in the world, he owed more to you than to anyone else, and he hated having you hampered by teaching. He admired your mind, and nothing would have pleased him more than helping you to do the work you do better than anyone else. If he were alive, that would be one of the first things he would use this money for."

"But he is not alive, and there was no word about me in his will, and so there is nothing to build your pretty theory upon. It's wonderfully nice of you and Louie, and I'm very pleased, you know."

"But Tom was so impractical, Father. He never thought it would mean more than a liberal dress allowance for me, if he thought at all. I don't know—he never spoke to me about it."

St. Peter smiled quizzically. "I'm not so sure about his impracticalness. When he was working on that gas, he once remarked to me that there might be a fortune in it. To be sure, he didn't wait to find out whether there was a fortune, but that had to do with quite another side of him. Yes. I think he knew his idea would make money and he wanted you to have it, with him or without him.

The young woman's face grew troubled. "Even if I married?"

"He wanted you to have whatever would make you happy."

She sighed luxuriously. "Louie has done that. The only thing that troubles me is, I feel you ought to have some of this money, that he would wish it. He was so full of gratitude, felt that he owed you so much."

Her father again rose, with that guarded, nervous movement. "Once and for all. Rosamond, understand that he owed me no more than I owed him. Nothing hurts me so much as to have any member of my family talk as if we had done something fine for that young man, brought him out, produced him. In a lifetime of teaching, I've encountered just one remarkable mind; but for that, I'd consider my good years largely wasted. And there can be no question of money between me and Tom Outland. I can't explain just how I feel about it, but it would somehow damage my recollections of him, would make that episode in my life commonplace like everything else. And that would be a great loss to me. I'm purely selfish in refusing your offer; my friendship with Outland is the one thing I will not have translated into the vulgar tongue."

His daughter looked perplexed and a little resentful.

"Sometimes," she murmured, "I think you feel I oughtn't to have taken it, either."

"You had no choice. For you it was settled by his own hand. Your bond with him was social, and it follows the laws of society, and they are based on property. Mine wasn't, and there was no material clause in it. He empowered you to carry out all his wishes, and I realize that you have responsibilities—but none toward me. There is Rodney Blake, of course, if he should ever turn up. You keep up some search for him?"

"Louie attends to it. He has investigated and rejected several impostors.

"Then, of course, there are other friends of Tom's. The Cranes, for instance?"

Rosamond' face grew hard. "I won't bother you about the Cranes, Papa. We will attend to them. Mrs. Crane is a common creature, and she is advised by that dreadful shyster brother of hers, Homer Bright. You know what he is."

"Oh, yes! He was about the greatest bluffer I ever had in my classes."

Rosamond had risen to go. "I want you to be awfully happy, daughter," St. Peter went on, and Tom did. It's only young people like you and Louie who can get any fun out of money. And there is enough to cover the fine, the almost imaginary obligations. You won't be sorry if you are generous with people like the Cranes."

"Thank you, Papa. I shan't forget." Rosamond went down the narrow stairway, leaving behind her a faint, fresh odour of lavender and orris-root, and her father lay down again on the box-couch. "A hint about the Cranes will be enough," he was thinking.

He didn't in the least understand his older daughter. Not that he pretended to understand Kathleen, either; but he usually knew how she would feel about things, and she had always seemed to need his protection more than Rosamond. When she was a student at the university, he used sometimes to see her crossing the campus alone, her head and shoulders lowered against the wind, her muff beside her face, her narrow skirt clinging close. There was something too plucky, too "I can-go-it-alone," about her quick step and jaunty little head; he didn't like it, it gave him a sudden pang. He would always call to her and catch up with her, and make her take his arm and be docile.

She had been much quicker at her lessons than Rosie, and very clever at water-colour portrait sketches. She had done several really good likenesses of her father- one, at least, was the man himself. With her mother she had no luck. She tried again and again, but the face was always hard, the upper lip longer than it seemed in life, the nose long and severe, and she made something cold and plaster-like of Lillian's beautiful complexion. "No, I don't see Mamma like that," she used to say, throwing out her chin. "Of course I don't! It just comes like that. She had done many heads of her sister, all very sentimental and curiously false, though Louie Marsellus protested to like them. Her drawing-teacher at the university had urged Kathleen to go to Chicago and study in the life classes at the Art Institute, but she said resolutely: "No, I can't really do anybody but Papa, and I can't make a living painting him."

"The only unusual thing about Kitty," her father used to tell his friends, "is that she doesn't think herself a bit unusual. Nowdays the girls in my classes who have a spark of aptitude for anything seem to think themselves remarkable."

Though wilfulness was implied in the line of her figure, in the way she sometimes threw out her chin, Kathleen had never been deaf to reasoning, deaf to her father, but once; and that was when, shortly after Rosamond's engagement to Tom, she announced that she was going to marry Scott McGregor. Scott was young, was just getting a start as a journalist, and his salary was not large enough for two people to live upon. That fact, the St. Peters thought, would act as a brake upon the impetuous young couple. But soon after they were engaged Scott began to do his daily prose poem for a newspaper syndicate. It was a success from the start, and increased his earnings enough to enable him to marry. The Professor had expected a better match for Kitty. He was no snob, and he liked Scott and trusted him; but he knew that Scott had a usual sort of mind, and Kitty had flashes of something quite different. Her father thought a more interesting man would make her happier. There was no holding her back, however, and the curious part of it was that, after the very first, her mother supported her. St. Peter had a vague suspicion that this was somehow on Rosamond's account more than on Kathleen's; Lillian always worked things out for Rosamond. Yet at the time he couldn't see how Kathleen's marriage would benefit Rosie. "Rosie is like your second self," he once declared to his wife, "but you never pampered yourself at her age as you do her".