Death Comes for the Archbishop

The Willa Cather Scholarly Edition

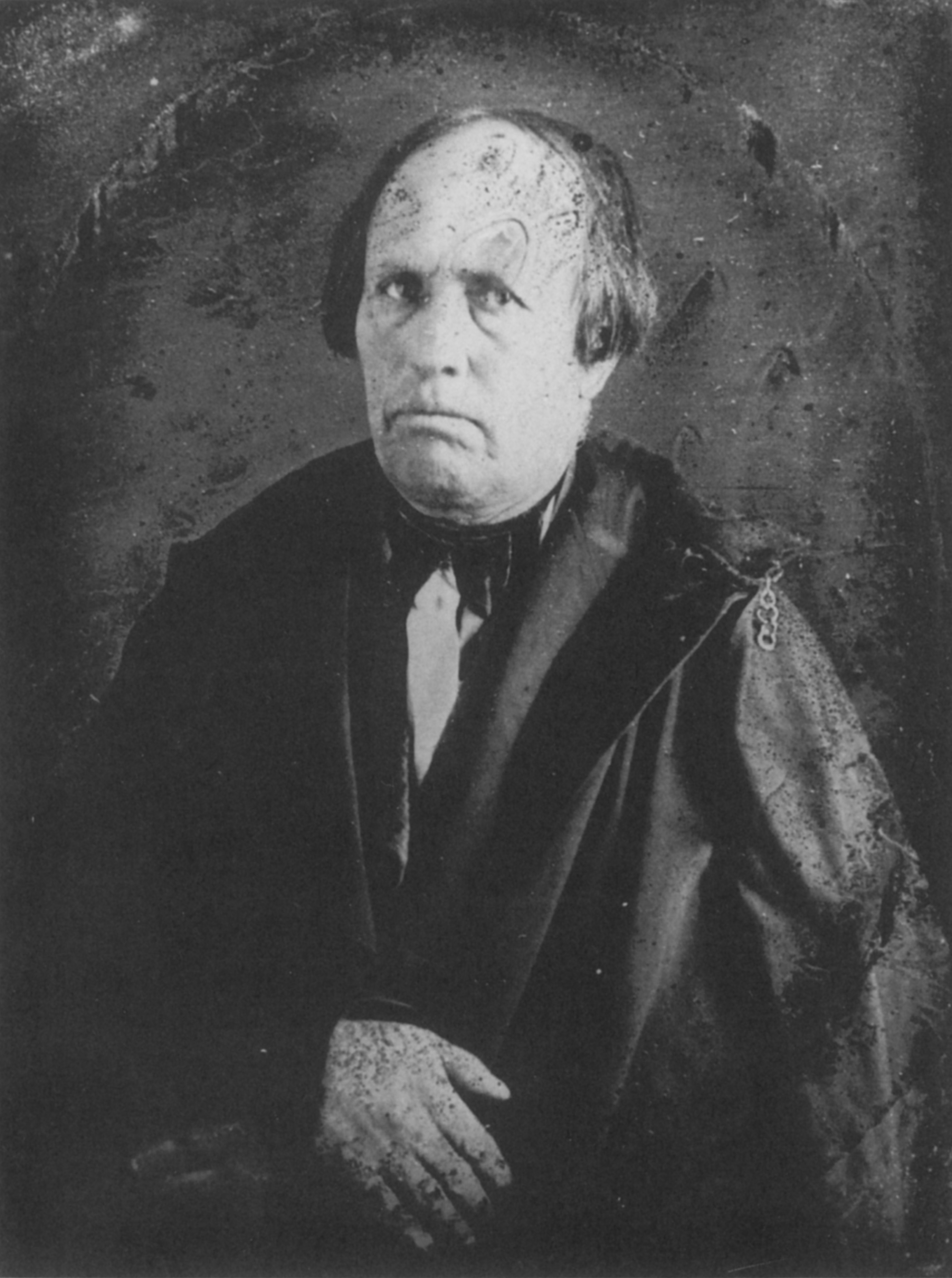

James Woodress

Charles W. Mignon

John J. Murphy

David Stouck

Gary Moulton

Paul A. Olson

Daniel J.J. Ross

University of Nebraska PressLincoln, 1997

Preface

THE objective of the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition is to provide to readers—present and future—various kinds of information relevant to Willa Cather's writing, obtained and presented according to the highest scholarly standards: a critical text faithful to her intention as she prepared it for the first edition, a historical essay providing relevant biographical and historical facts, explanatory notes identifying allusions and references, a textual commentary tracing the work through its lifetime and describing Cather's involvement with it, and a record of changes in the text's various versions. This edition is distinctive in the comprehensiveness of its apparatus, especially in its inclusion of extensive explanatory information that illuminates the fiction of a writer who drew so extensively upon actual experience, as well as the full textual information we have come to expect in a modern critical edition. It thus connects activities that are too often separate—literary scholarship and textual editing.

Editing Cather's writing means recognizing that Cather was as fiercely protective of her novels as she was of her private life. She suppressed much of her early writing and dismissed serial publication of later work, discarded manuscripts and proofs, destroyed letters, and included in her will a stipulation against publication of her private papers. Yet the record remains surprisingly full. Manuscripts, typescripts, and proofs of some texts survive with corrections and revisions in Cather's hand; serial publications provide final "draft" versions of texts; correspondence with her editors and publishers help clarify her intention for a work, and publishers' records detail each book's public life; correspondence with friends and acquaintances provides an intimate view of her writing; published interviews with and speeches by Cather provide a running public commentary on her career; and through their memoirs, recollections, and letters, Cather's contemporaries provide their own commentary on circumstances surrounding her writing.

In assembling pieces of the editorial puzzle, we have been guided by principles and procedures articulated by the Committee on Scholarly Editions of the Modern Language Association. Assembling and comparing texts demonstrated the basic tenet of the textual editor—that only painstaking collations reveal what is actually there. Scholars had assumed, for example, that with the exception of a single correction in spelling, O Pioneers! passed unchanged from the 1913 first edition to the 1937 Autograph Edition. Collations revealed nearly a hundred word changes, thus providing information not only necessary to establish a critical text and to interpret how Cather composed, but also basic to interpreting how her ideas about art changed as she matured.

Cather's revisions and corrections on typescripts and page proofs demonstrate that she brought to her own writing her extensive experience as an editor. Word changes demonstrate her practices in revising; other changes demonstrate that she gave extraordinarily close scrutiny to such matters as capitalization, punctuation, paragraphing, hyphenation, and spacing. Knowledgeable about production, Cather had intentions for her books that extended to their design and manufacture. For example, she specified typography, illustrations, page format, paper stock, ink color, covers, wrappers, and advertising copy.

To an exceptional degree, then, Cather gave to her work the close textual attention that modern editing practices respect, while in other ways she challenged her editors to expand the definition of "corruption" and "authoritative" beyond the text, to include the book's whole format and material existence. Believing that a book's physical form influenced its relationship with a reader, she selected type, paper, and format that invited the reader response she sought. The heavy texture and cream color of paper used for O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, for example, created a sense of warmth and invited a childlike play of imagination, as did these books' large dark type and wide margins. By the same principle, she expressly rejected the anthology format of assembling texts of numerous novels within the covers of one volume, with tight margins, thin paper, and condensed print.

Given Cather's explicitly stated intentions for her works, printing and publishing decisions that disregard her wishes represent their own form of corruption, and an authoritative edition of Cather must go beyond the sequence of words and punctuation to include other matters: page format, paper stock, typeface, and other features of design. The volumes in the Cather Edition respect those intentions insofar as possible within a series format that includes a comprehensive scholarly apparatus. For example, the Cather Edition has adopted the format of six by nine inches, which Cather approved in Bruce Rogers's elegant work on the 1937 Houghton Mifflin Autograph Edition, to accommodate the various elements of design. While lacking something of the intimacy of the original page, this size permits the use of large, generously leaded type and ample margins—points of style upon which the author was so insistent. In the choice of paper, we have deferred to Cather's declared preference for a warm, cream antique stock.

Today's technology makes it difficult to emulate the qualities of hot-metal typesetting and letterpress printing. In comparison, modern phototypesetting printed by offset lithography tends to look anemic and lacks the tactile quality of type impressed into the page. The version of the Old Style No. 31 typeface employed in the original edition of Death Comes for the Archbishop, were it available for phototypesetting, would hardly survive the transition. Instead, we have chosen Linotype Janson Text, a modern rendering of the type used by Rogers. The subtle adjustments of stroke weight in this reworking do much to retain the integrity of earlier metal versions. Therefore, without trying to replicate the design of single works, we seek to represent Cather's general preferences in a design that encompasses many volumes.

In each volume in the Cather Edition, the author's specific intentions for design and printing are set forth in textual commentaries. These essays also describe the history of the texts, identify those that are authoritative, explain the selection of copy-texts or basic texts, justify emendations of the copy-text, and describe patterns of variants. The textual apparatus in each volume—lists of variants, emendations, explanations of emendations, and end-line hyphenations—completes the textual story.

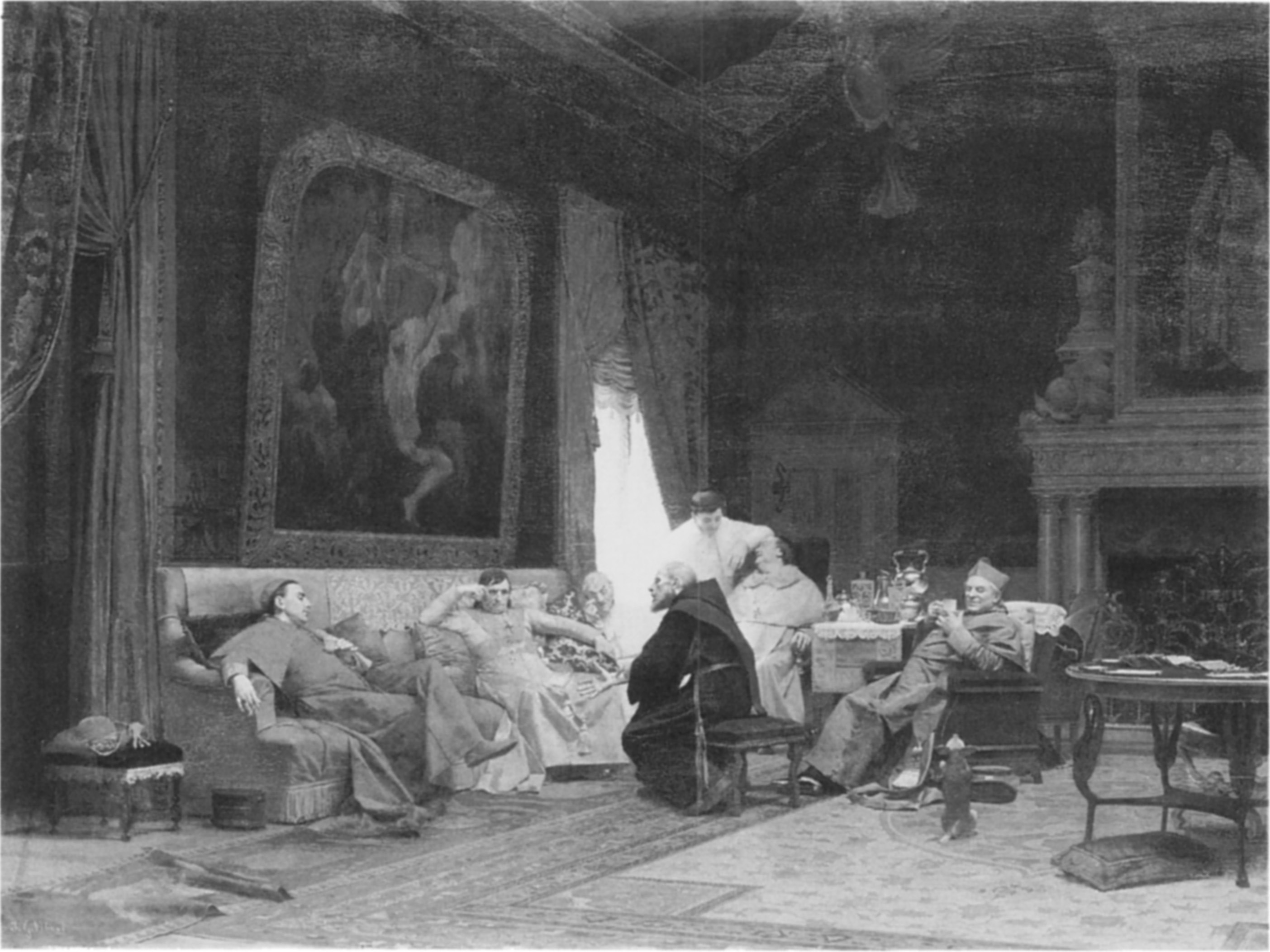

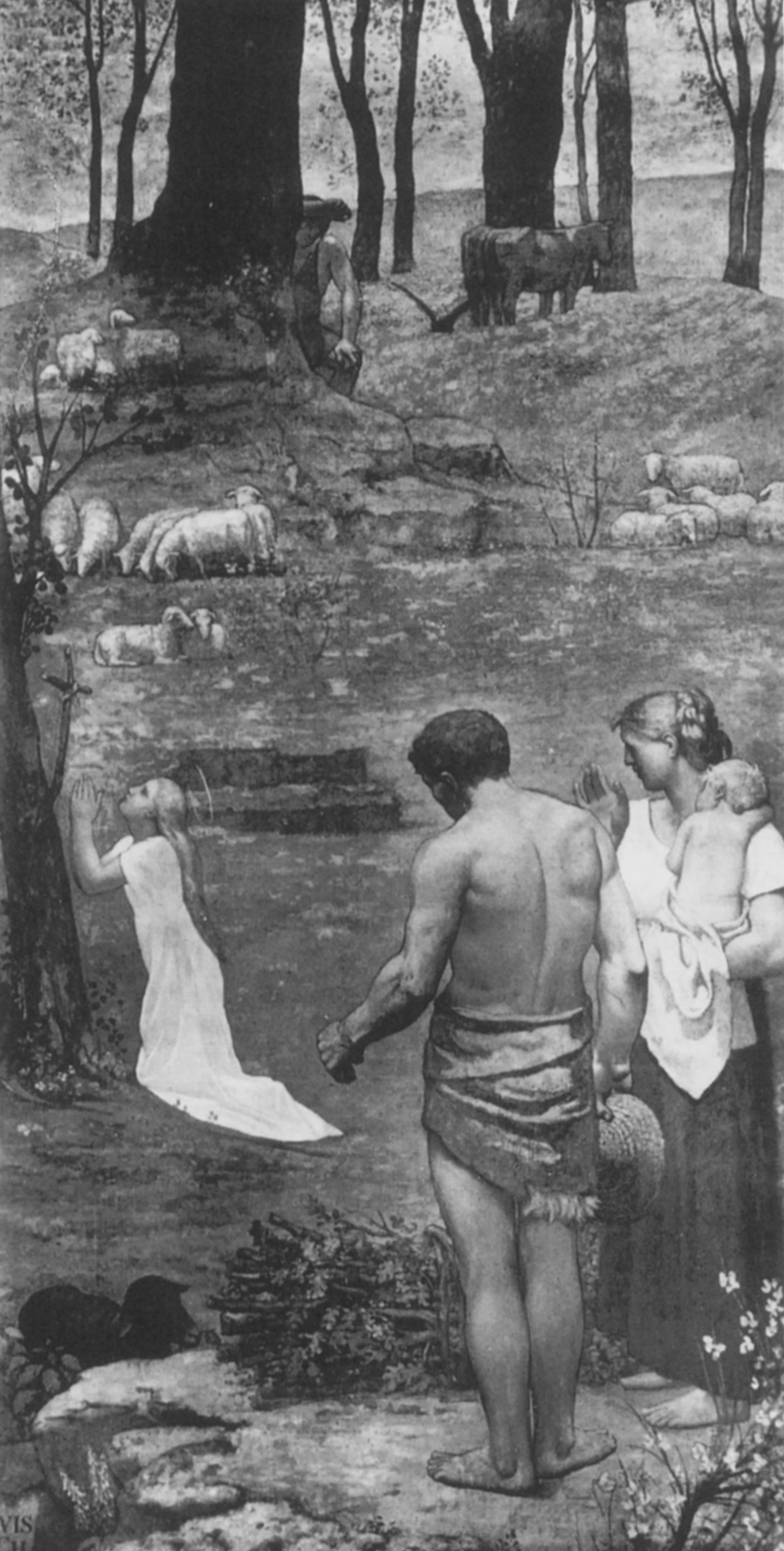

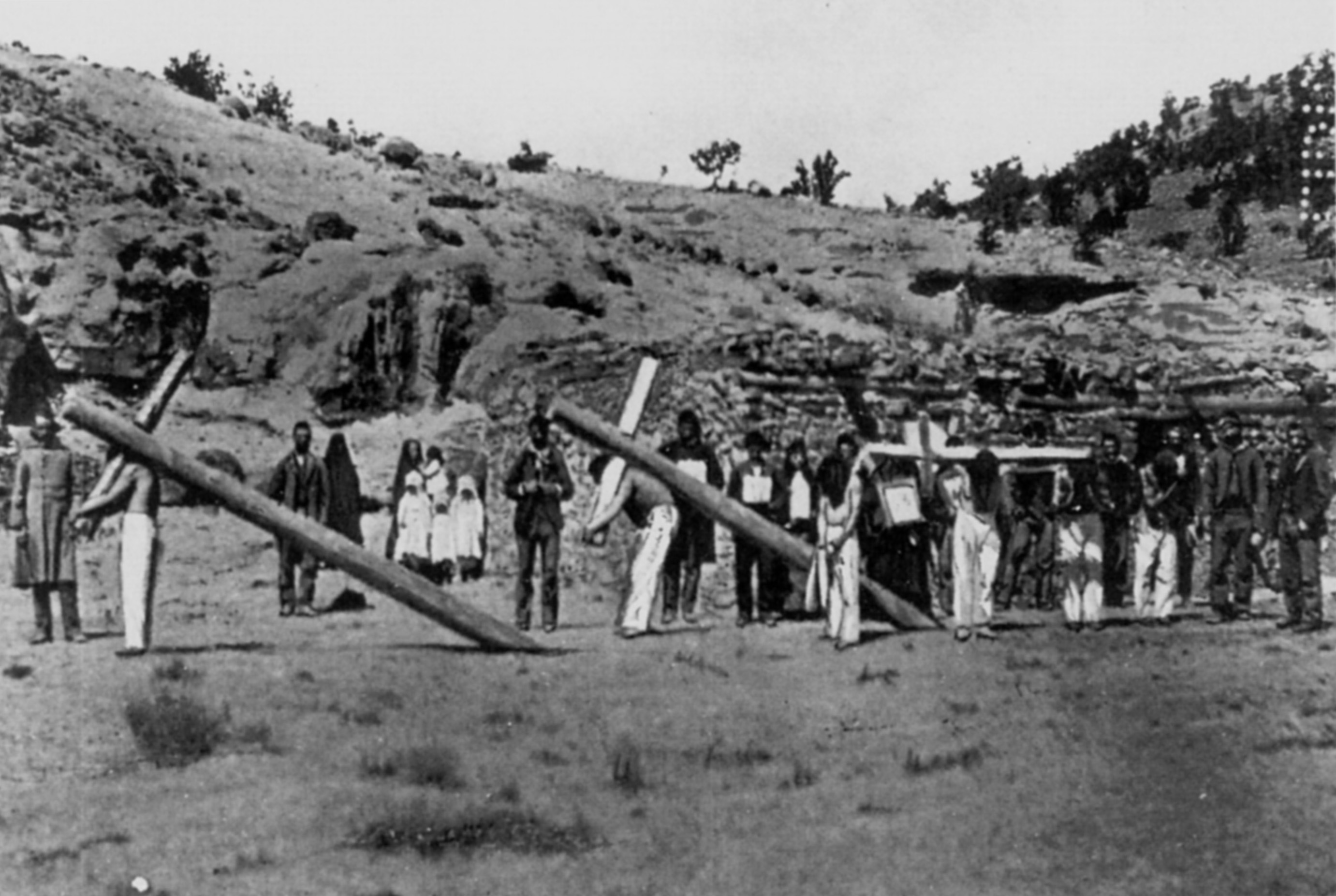

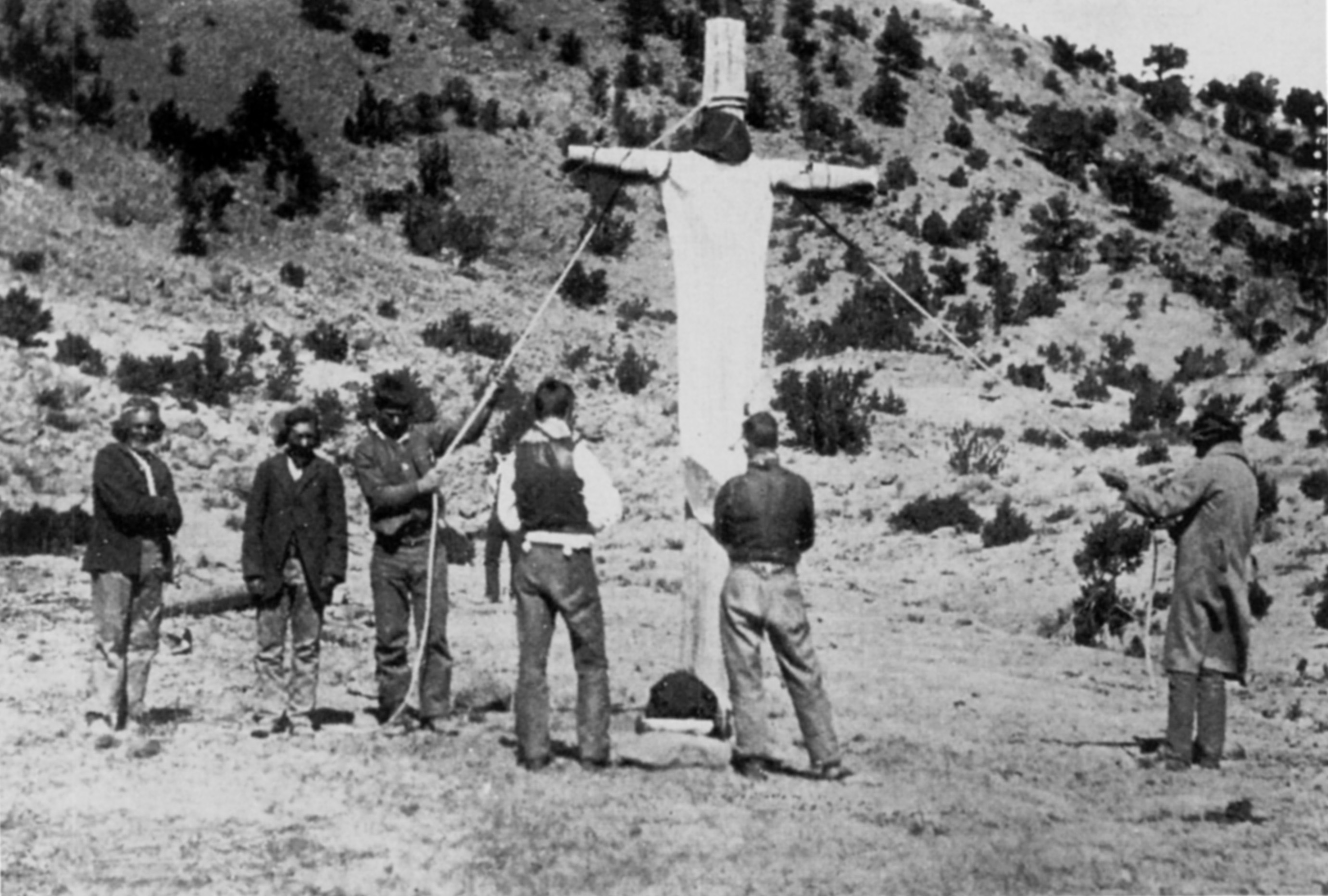

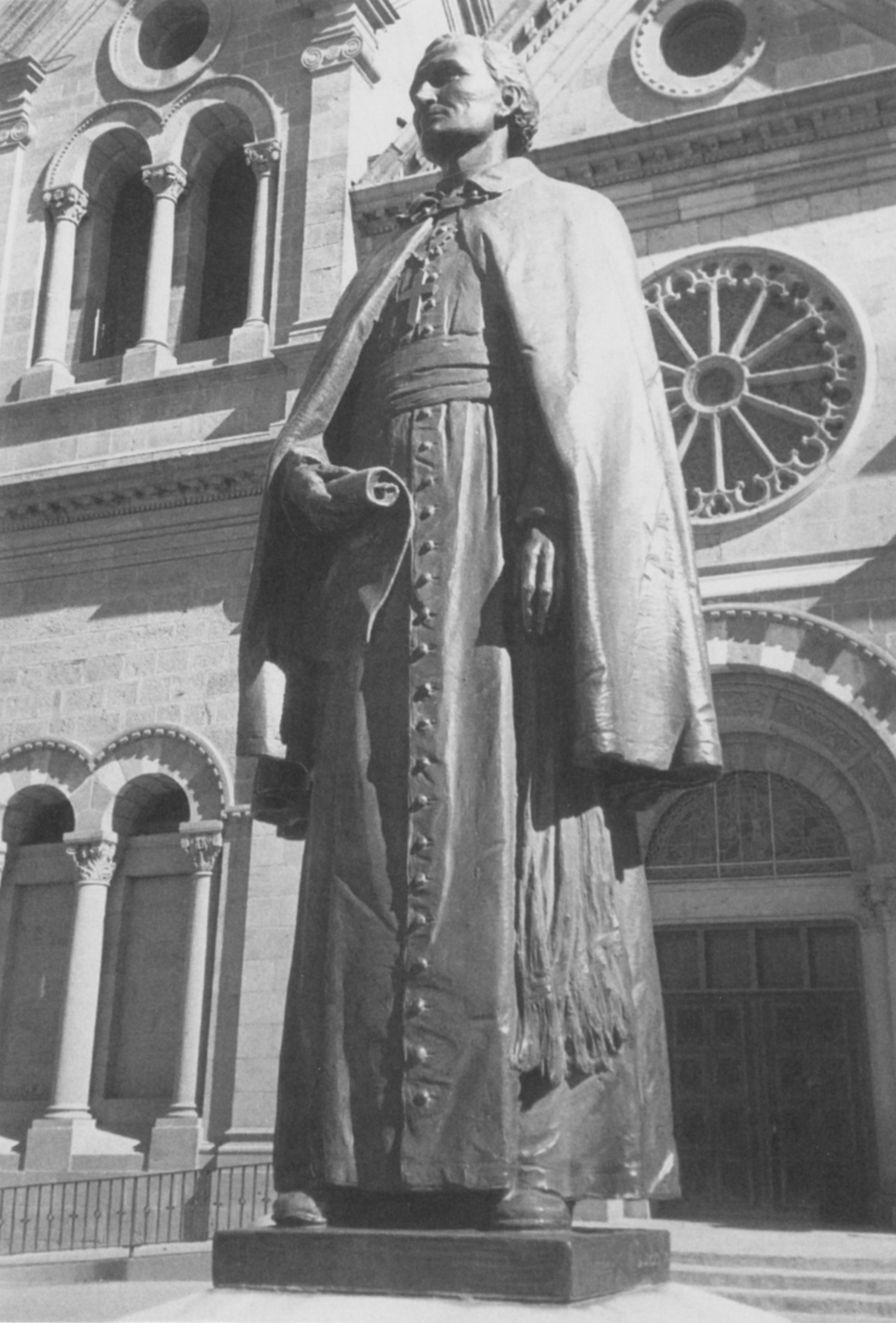

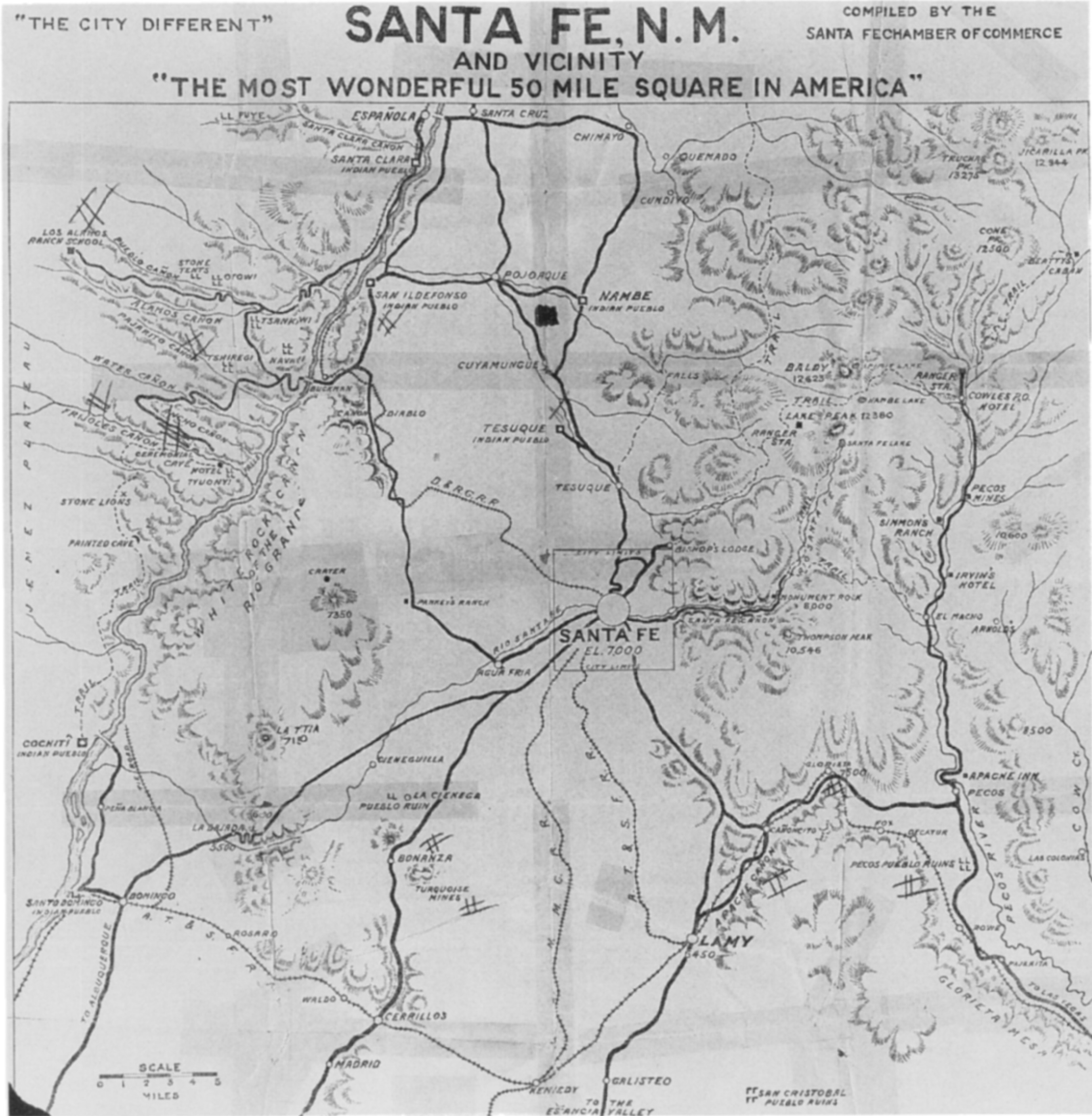

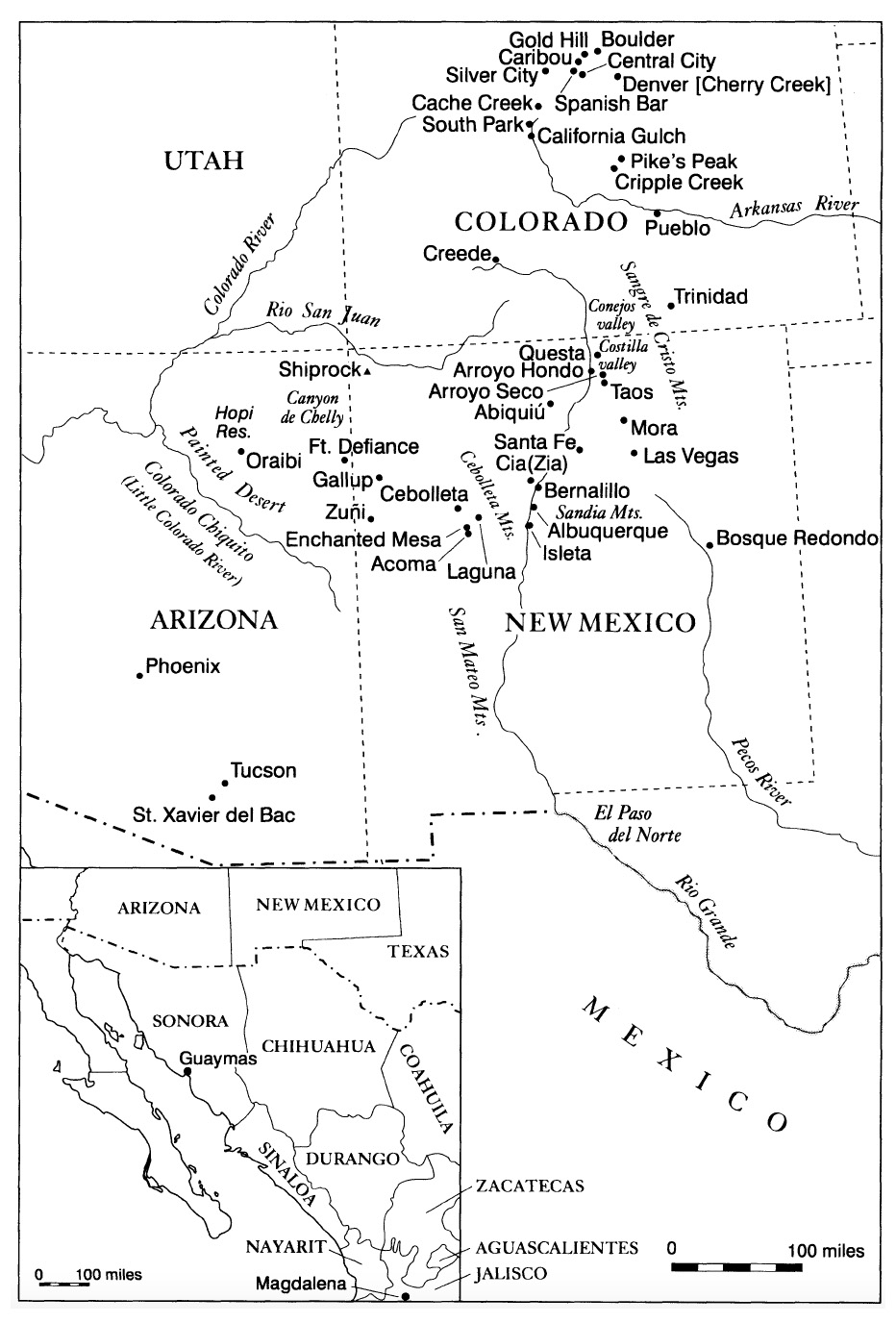

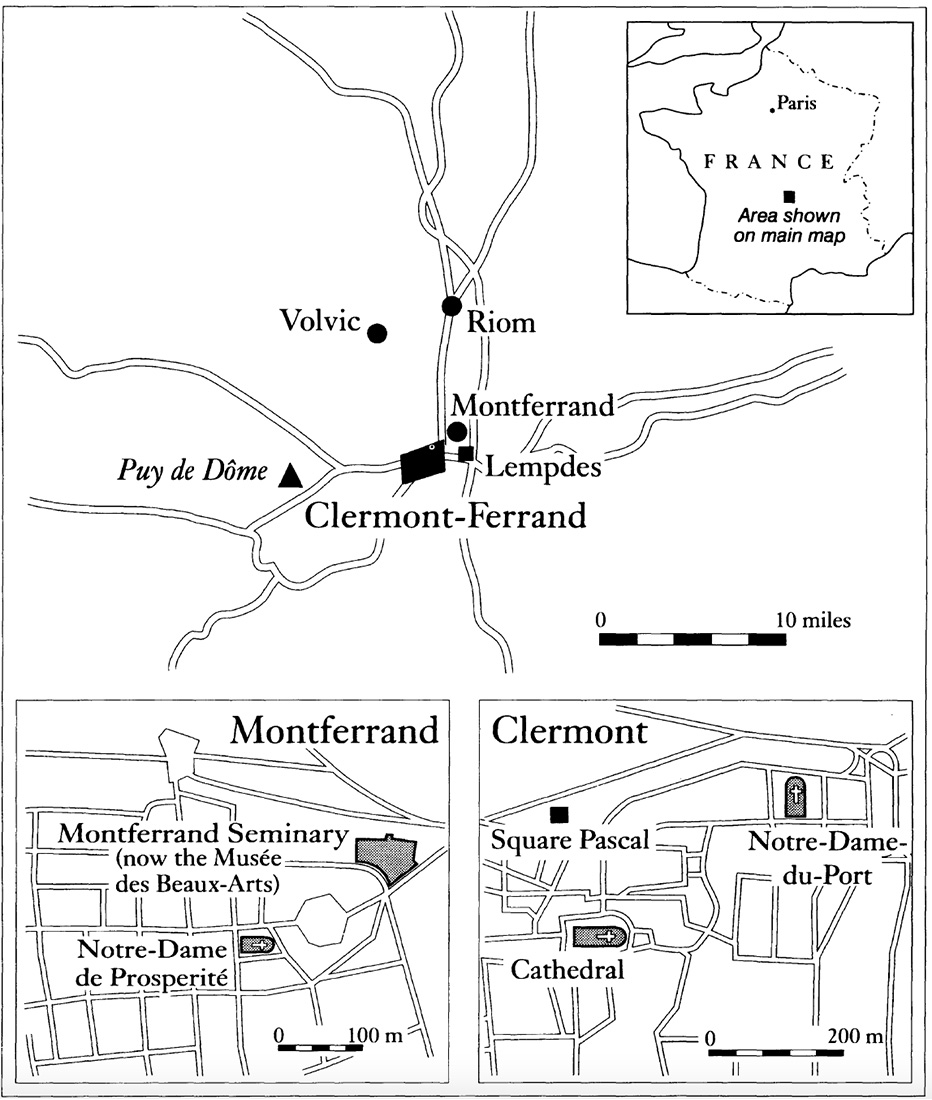

Historical essays provide essential information about the genesis, form, and transmission of each book, as well as supply its biographical, historical, and intellectual contexts. Illustrations supplement these essays with photographs, maps, and facsimiles of manuscript, typescript, or typeset pages. Finally, because Cather in her writing drew so extensively upon personal experience and historical detail, explanatory notes are an especially important part of the Cather Edition. By providing a comprehensive identification of her references to flora and fauna, to regional customs and manners, to the classics and the Bible, to popular writing, music, and other arts—as well as relevant cartography and census material—these notes provide a starting place for scholarship and criticism on subjects long slighted or ignored.

Within this overall standard format, differences occur that are informative in their own right. The straightforward textual history of O Pioneers! and My Ántonia contrasts with the more complicated textual challenges of A Lost Lady and Death Comes for the Archbishop; the allusive personal history of the Nebraska novels, so densely woven that My Ántonia seems drawn not merely upon Anna Pavelka but upon all of Webster County, contrasts with the more public allusions of novels set elsewhere. The Cather Edition reflects the individuality of each work while providing a standard of reference for critical study.

Contents

Prologue

AT ROME

One summer evening in the year 1848, three Cardinals and a missionary Bishop from America were dining together in the gardens of a villa in the Sabine hills, overlooking Rome. The villa was famous for the fine view from its terrace. The hidden garden in which the four men sat at table lay some twenty feet below the south end of this terrace, and was a mere shelf of rock, overhanging a steep declivity planted with vineyards. A flight of stone steps connected it with the promenade above. The table stood in a sanded square, among potted orange and oleander trees, shaded by spreading oaks that grew out of the rocks overhead. Beyond the balustrade was the drop into the air, and far below the landscape stretched soft and undulating; there was nothing to arrest the eye until it reached Rome itself.

It was early when the Spanish Cardinal and his guests sat down to dinner. The sun was still good for an hour of supreme splendour, and across the shining folds of country the low profile of the city barely fretted the sky-line — indistinct except for the dome of St. Peter's, bluish grey like the flattened top of a great balloon, just a flash of copper light on its soft metallic surface. The Cardinal had an eccentric preference for beginning his dinner at this time in the late afternoon, when the vehemence of the sun suggested motion. The light was full of action and had a peculiar quality of climax — of splendid finish. It was both intense and soft, with a ruddiness as of much-multiplied candlelight, an aura of red in its flames. It bored into the ilex trees, illuminating their mahogany trunks and blurring their dark foliage; it warmed the bright green of the orange trees and the rose of the oleander blooms to gold; sent congested spiral patterns quivering over the damask and plate and crystal. The churchmen kept their rectangular clerical caps on their heads to protect them from the sun. The three Cardinals wore black cassocks with crimson pipings and crimson buttons, the Bishop a long black coat over his violet vest.

They were talking business; had met, indeed, to discuss an anticipated appeal from the Provincial Council at Baltimore for the founding of an Apostolic Vicarate in New Mexico—a part of North America recently annexed to the United States. This new territory was vague to all of them, even to the missionary Bishop. The Italian and French Cardinals spoke of it as Le Mexique, and the Spanish host referred to it as "New Spain." Their interest in the projected Vicarate was tepid, and had to be continually revived by the missionary, Father Ferrand; Irish by birth, French by ancestry—a man of wide wanderings and notable achievement in the New World, an Odysseus of the Church. The language spoken was French—the time had already gone by when Cardinals could conveniently discuss contemporary matters in Latin.

The French and Italian Cardinals were men in vigorous middle life—the Norman full-belted and ruddy, the Venetian spare and sallow and hook-nosed. Their host, García María de Allande, was still a young man. He was dark in colouring, but the long Spanish face, that looked out from so many canvases in his ancestral portrait gallery, was in the young Cardinal much modified through his English mother. With his caffè oscuro eyes, he had a fresh, pleasant English mouth, and an open manner.

During the latter years of the reign of Gregory XVI, de Allande had been the most influential man at the Vatican; but since the death of Gregory, two years ago, he had retired to his country estate. He believed the reforms of the new Pontiff impractical and dangerous , and had withdrawn from politics, confining his activities to work for the Society for the Propagation of the Faith—that organization which had been so fostered by Gregory. In his leisure the Cardinal played tennis. As a boy, in England, he had been passionately fond of this sport. Lawn tennis had not yet come into fashion; it was a formidable game of indoor tennis the Cardinal played. Amateurs of that violent sport came from Spain and France to try their skill against him.

The missionary, Bishop Ferrand, looked much older than any of them, old and rough — except for his clear, intensely blue eyes. His diocese lay within the icy arms of the Great Lakes, and on his long, lonely horseback rides among his missions the sharp winds had bitten him well. The missionary was here for a purpose, and he pressed his point. He ate more rapidly than the others and had plenty of time to plead his cause, — finished each course with such dispatch that the Frenchman remarked he would have been an ideal dinner companion for Napoleon.

The Bishop laughed and threw out his brown hands in apology. "Likely enough I have forgot my manners. I

am preoccupied. Here you can scarcely understand what it means that the United States has annexed that enormous territory which was the cradle of the Faith in the New World. The Vicarate of New Mexico will be in a few years raised to an Episcopal See, with jurisdiction over a country larger than Central and Western Europe. The Bishop of that See will direct the beginning of momentous things."

"Beginnings," murmured the Venetian, "there have been so many. But nothing ever comes from over there but trouble and appeals for money."

The missionary turned to him patiently. "Your Eminence, I beg you to follow me. This country was evangelized in fifteen hundred, by the Franciscan Fathers. It has been allowed to drift for nearly three hundred years and is not yet dead. It still pitifully calls itself a Catholic country, and tries to keep the forms of religion without instruction. The old mission churches are in ruins. The few priests are without guidance or discipline. They are lax in religious observance, and some of them live in open concubinage. If this Augean stable is not cleansed, now that the territory has been taken over by a progressive government, it will prejudice the interests of the Church in the whole of North America."

"But these missions are still under the jurisdiction of Mexico, are they not?" inquired the Frenchman.

"In the See of the Bishop of Durango?" added María de Allande.

The missionary sighed. "Your Eminence, the Bishop of Durango is an old man; and from his seat to Santa Fé is a distance of fifteen hundred English miles. There are no wagon roads, no canals, no navigable rivers. Trade is carried on by means of pack-mules, over treacherous trails. The desert down there has a peculiar horror; I do not mean thirst, nor Indian massacres, which are frequent. The very floor of the world is cracked open into countless canyons and arroyos, fissures in the earth which are sometimes ten feet deep, sometimes a thousand. Up and down these stony chasms the traveller and his mules clamber as best they can. It is impossible to go far in any direction without crossing them. If the Bishop of Durango should summon a disobedient priest by letter, who shall bring the Padre to him? Who can prove that he ever received the summons? The post is carried by hunters, fur trappers, gold-seekers, whoever happens to be moving on the trails."

The Norman Cardinal emptied his glass and wiped his lips.

"And the inhabitants, Father Ferrand? If these are the travellers, who stays at home?"

"Some thirty Indian nations, Monsignor, each with

its own customs and language, many of them fiercely hostile to each other. And the Mexicans, a naturally devout people. Untaught and unshepherded, they cling to the faith of their fathers."

"I have a letter from the Bishop of Durango, recommending his Vicar for this new post," remarked María de Allande.

"Your Eminence, it would be a great misfortune if a native priest were appointed; they have never done well in that field. Besides, this Vicar is old. The new Vicar must be a young man, of strong constitution, full of zeal, and above all, intelligent. He will have to deal with savagery and ignorance, with dissolute priests and political intrigue. He must be a man to whom order is necessary—as dear as life."

The Spaniard's coffee-coloured eyes showed a glint of yellow as he glanced sidewise at his guest. "I suspect, from your exordium, that you have a candidate — and that he is a French priest, perhaps?"

"You guess rightly, Monsignor. I am glad to see that we have the same opinion of French missionaries."

"Yes," said the Cardinal lightly, "they are the best missionaries. Our Spanish fathers made good martyrs, but the French Jesuits accomplish more. They are the great organizers."

"Better than the Germans?" asked the Venetian, who had Austrian sympathies.

"Oh, the Germans classify, but the French arrange! The French missionaries have a sense of proportion and rational adjustment. They are always trying to dis cover the logical relation of things. It is a passion with them." Here the host turned to the old Bishop again. "But your Grace, why do you neglect this Burgundy? I had this wine brought up from my cellar especially to warm away the chill of your twenty Canadian winters. Surely, you do not gather vintages like this on the shores of the Great Lake Huron?"

The missionary smiled as he took up his untouched glass. "It is superb, your Eminence, but I fear I have lost my palate for vintages. Out there, a little whisky, or Hudson's Bay Company rum, does better for us. I must confess I enjoyed the champagne in Paris. We had been forty days at sea, and I am a poor sailor."

"Then we must have some for you." He made a sign to his major-domo. "You like it very cold? And your new Vicar Apostolic, what will he drink in the country of bison and serpents à sonnettes? And what will he eat?"

"He will eat dried buffalo meat and frijoles with chili, and he will be glad to drink water when he can get it. He will have no easy life, your Eminence. That country will

drink up his youth and strength as it does the rain. He will be called upon for every sacrifice, quite possibly for martyrdom. Only last year the Indian pueblo of San Fernandez de Taos murdered and scalped the American Governor and some dozen other whites. The reason they did not scalp their Padre was that their Padre was one of the leaders of the rebellion and himself planned the massacre. That is how things stand in New Mexico!"

"Where is your candidate at present, Father?"

"He is a parish priest, on the shores of Lake Ontario, in my diocese. I have watched his work for nine years. He is but thirty-five now. He came to us directly from the Seminary."

"And his name is?"

"Jean Marie Latour."

María de Allande, leaning back in his chair, put the tips of his long fingers together and regarded them thoughtfully.

"Of course, Father Ferrand, the Propaganda will almost certainly appoint to this Vicarate the man whom the Council at Baltimore recommends."

"Ah yes, your Eminence; but a word from you to the Provincial Council, an inquiry, a suggestion —"

"Would have some weight, I admit," replied the Car

dinal smiling. "And this Latour is intelligent, you say? What a fate you are drawing upon him! But I suppose it is no worse than a life among the Hurons. My knowledge of your country is chiefly drawn from the romances of Fenimore Cooper, which I read in English with great pleasure. But has your priest a versatile intelligence? Any intelligence in matters of art, for example?"

"And what need would he have for that, Monsignor? Besides, he is from Auvergne."

The three Cardinals broke into laughter and refilled their glasses. They were all becoming restive under the monotonous persistence of the missionary.

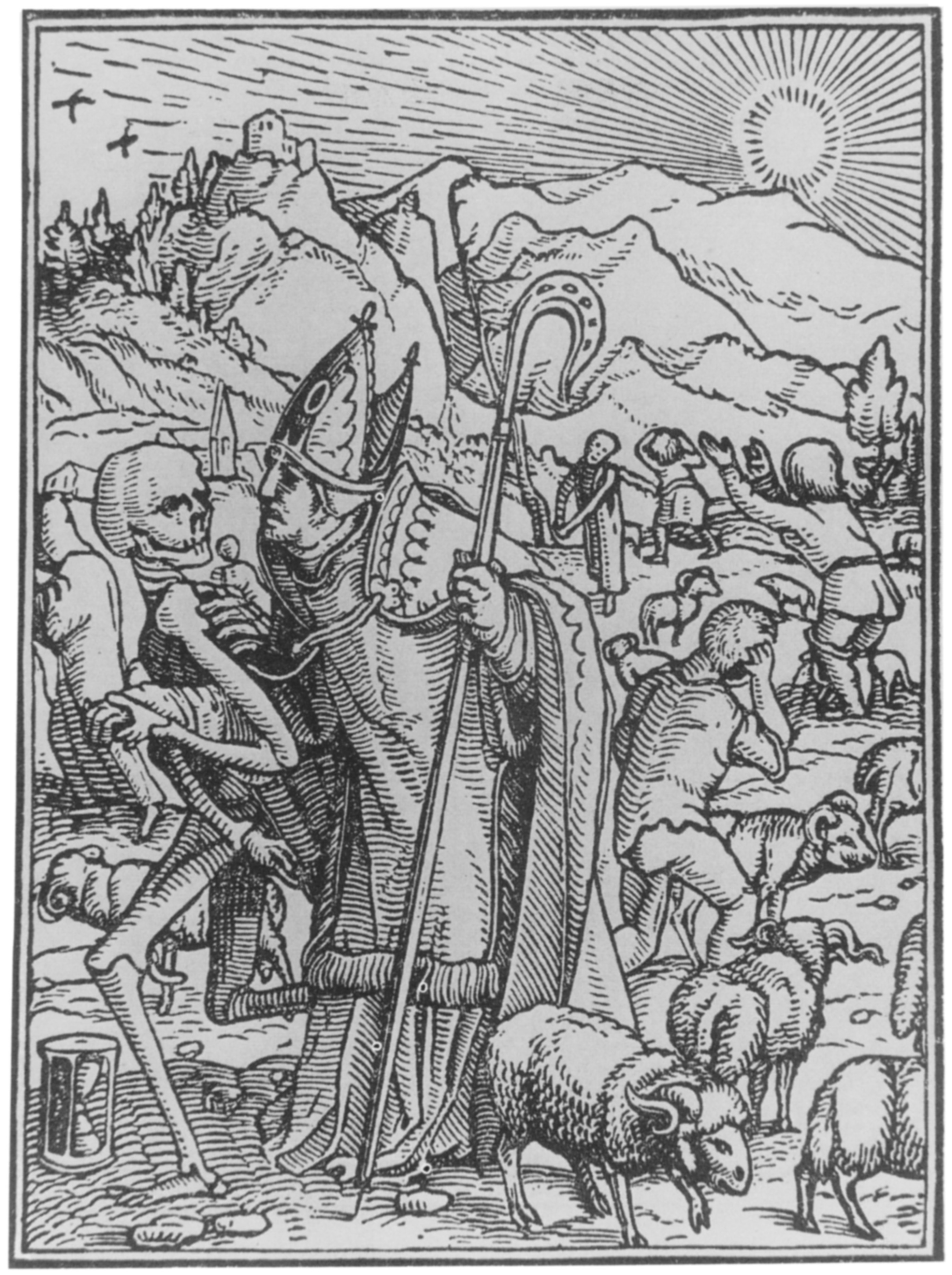

"Listen," said the host, "and I will relate a little story, while the Bishop does me the compliment to drink my champagne. I have a reason for asking this question which you have answered so finally. In my family house in Valencia I have a number of pictures by the great Spanish painters, collected chiefly by my great-grandfather, who was a man of perception in these things and, for his time, rich. His collection of El Greco is, I believe, quite the best in Spain. When my progenitor was an old man, along came one of these missionary priests from New Spain, begging. All missionaries from the Americas were inveterate beggars,

then as now, Bishop Ferrand. This Franciscan had considerable success, with his tales of pious Indian converts and struggling missions. He came to visit at my greatgrandfather's house and conducted devotions in the absence of the Chaplain. He wheedled a good sum of money out of the old man, as well as vestments and linen and chalices — he would take anything— and he implored my grandfather to give him a painting from his great collection, for the ornamentation of his mission church among the Indians. My grandfather told him to choose from the gallery, believing the priest would covet most what he himself could best afford to spare. But not at all; the hairy Franciscan pounced upon one of the best in the collection; a young St. Francis in meditation, by El Greco, and the model for the saint was one of the very handsome Dukes of Albuquerque. My grandfather protested; tried to persuade the fellow that some picture of the Crucifixion, or a martyrdom, would appeal more strongly to his redskins. What would a St. Francis, of almost feminine beauty, mean to the scalp-takers?

"All in vain. The missionary turned upon his host with a reply which has become a saying in our family: 'You refuse me this picture because it is a good picture. It is too good for God, but it is not too good for you.'

"He carried off the painting. In my grandfather's manuscript catalogue, under the number and title of the St. Francis, is written: Given to Fray Teodocio,for the glory of God, to enrich his mission church at Pueblo de Cia, among the savages of New Spain.

"It is because of this lost treasure, Father Ferrand, that I happened to have had some personal correspondence with the Bishop of Durango. I once wrote the facts to him fully. He replied to me that the mission at Cia was long ago destroyed and its furnishings scattered. Of course the painting may have been ruined in a pillage or massacre. On the other hand, it may still be hidden away in some crumbling sacristy or smoky wigwam. If your French priest had a discerning eye, now, and were sent to this Vicarate, he might keep my El Greco in mind."

The Bishop shook his head. "No, I can't promise you — I do not know. I have noticed that he is a man of severe and refined tastes, but he is very reserved. Down there the Indians do not dwell in wigwams, your Eminence," he added gently.

"No matter, Father. I see your redskins through Fenimore Cooper, and I like them so. Now let us go to the terrace for our coffee and watch the evening come on."

The Cardinal led his guests up the narrow stairway.

The long gravelled terrace and its balustrade were blue as a lake in the dusky air. Both sun and shadows were gone. The folds of russet country were now violet. Waves of rose and gold throbbed up the sky from behind the dome of the Basilica.

As the churchmen walked up and down the promenade, watching the stars come out, their talk touched upon many matters, but they avoided politics, as men are apt to do in dangerous times. Not a word was spoken of the Lombard war, in which the Pope's position was so anomalous. They talked instead of a new opera by young Verdi, which was being sung in Venice; of the case of a Spanish dancing-girl who had lately become a religious and was said to be working miracles in Andalusia. In this conversation the missionary took no part, nor could he even follow it with much interest. He asked himself whether he had been on the frontier so long that he had quite lost his taste for the talk of clever men. But before they separated for the night María de Allande spoke a word in his ear, in English.

"You are distrait, Father Ferrand. Are you wishing to unmake your new Bishop already? It is too late. Jean Marie Latour — am I right?"

BOOK ONE

THE VICAR APOSTOLIC

1

THE CRUCIFORM TREE

One afternoon in the autumn of 1851 a solitary horseman, followed by a pack-mule, was pushing through an arid stretch of country somewhere in central New Mexico. He had lost his way, and was trying to get back to the trail, with only his compass and his sense of direction for guides. The difficulty was that the country in which he found himself was so featureless— or rather, that it was crowded with features, all exactly alike. As far as he could see, on every side, the landscape was heaped up into monotonous red sand-hills, not much larger than haycocks, and very much the shape of haycocks. One could not have believed that in the number of square miles a man is able to sweep with the eye there could be so many uniform red hills. He had been riding among them since early morning, and the look of the country had no more changed than if he had stood still. He must have travelled through thirty miles of these conical red hills, winding his way in the narrow cracks between them, and he had begun to think that he would never see anything else. They were so exactly like one another that he seemed to be wandering in some geometrical nightmare; flattened cones, they were, more the shape of Mexican ovens than haycocks— yes, exactly the shape of Mexican ovens, red as brick-dust, and naked of vegetation except for small juniper trees. And the junipers, too, were the shape of Mexican ovens. Every conical hill was spotted with smaller cones of juniper, a uniform yellowish green, as the hills were a uniform red. The hills thrust out of the ground so thickly that they seemed to be pushing each other, elbowing each other aside, tipping each other over.

The blunted pyramid, repeated so many hundred times upon his retina and crowding down upon him in the heat, had confused the traveller, who was sensitive to the shape of things.

"Mais, c'est fantastique!" he muttered, closing his eyes to rest them from the intrusive omnipresence of the triangle.

When he opened his eyes again, his glance immediately fell upon one juniper which differed in shape from the others. It was not a thick-growing cone, but a naked, twisted trunk, perhaps ten feet high, and at the top it parted into two lateral, flat-lying branches, with a little crest of green in the centre, just above the cleavage. Living vegetation could not present more faithfully the form of the Cross.

The traveller dismounted, drew from his pocket a much worn book, and baring his head, knelt at the foot of the cruciform tree.

Under his buckskin riding-coat he wore a black vest and the cravat and collar of a churchman. A young priest, at his devotions; and a priest in a thousand, one knew at a glance. His bowed head was not that of an ordinary man,— it was built for the seat of a fine intelligence. His brow was open, generous, reflective, his features handsome and somewhat severe. There was a singular elegance about the hands below the fringed cuffs of the buckskin jacket. Everything showed him to be a man of gentle birth— brave, sensitive, courteous. His manners, even when he was alone in the desert, were distinguished. He had a kind of courtesy toward himself, toward his beasts, toward the juniper tree before which he knelt, and the God whom he was addressing.

His devotions lasted perhaps half an hour, and when he rose he looked refreshed. He began talking to his mare in halting Spanish, asking whether she agreed with him that it would be better to push on, weary as she was, in hope of finding the trail. He had no water left in his canteen, and the horses had had none since yesterday morning. They had made a dry camp in these hills last night. The animals were almost at the end of their endurance, but they would not recuperate until they got water, and it seemed best to spend their last strength in searching for it.

On a long caravan trip across Texas this man had had some experience of thirst, as the party with which he travelled was several times put on a meagre water ration for days together. But he had not suffered then as he did now. Since morning he had had a feeling of illness; the taste of fever in his mouth, and alarming seizures of vertigo. As these conical hills pressed closer and closer upon him, he began to wonder whether his long wayfaring from the mountains of Auvergne were possibly to end here. He reminded himself of that cry, wrung from his Saviour on the Cross, "J'ai soif!" Of all our Lord's physical sufferings, only one, "I thirst," rose to His lips. Empowered by long training, the young priest blotted himself out of his own consciousness and meditated upon the anguish of his Lord. The Passion of Jesus became for him the only reality; the need of his own body was but a part of that conception.

His mare stumbled, breaking his mood of contemplation. He was sorrier for his beasts than for himself. He, supposed to be the intelligence of the party, had got the poor animals into this interminable desert of ovens. He was afraid he had been absent-minded, had been pondering his problem instead of heeding the way. His problem was how to recover a Bishopric. He was a Vicar Apostolic, lacking a Vicarate. He was thrust out; his flock would have none of him.

The traveller was Jean Marie Latour, consecrated Vicar Apostolic of New Mexico and Bishop of Agathonica in partibus at Cincinnati a year ago —and ever since then he had been trying to reach his Vicarate. No one in Cincinnati could tell him how to get to New Mexico no one had ever been there. Since young Father Latour's arrival in America, a railroad had been built through from New York to Cincinnati; but there it ended. New Mexico lay in the middle of a dark continent. The Ohio merchants knew of two routes only. One was the Santa Fé trail from St. Louis, but at that time it was very dangerous because of Comanche Indian raids. His friends advised Father Latour to go down the river to New Orleans, thence by boat to Galveston, across Texas to San Antonio, and to wind up into New Mexico along the Rio Grande valley. This he had done, but with what misadventures!

His steamer was wrecked and sunk in the Galveston harbour, and he had lost all his worldly possessions except his books, which he saved at the risk of his life. He crossed Texas with a traders' caravan, and approaching San Antonio he was hurt in jumping from an overturning wagon, and had to lie for three months in the crowded house of a poor Irish family, waiting for his injured leg to get strong.

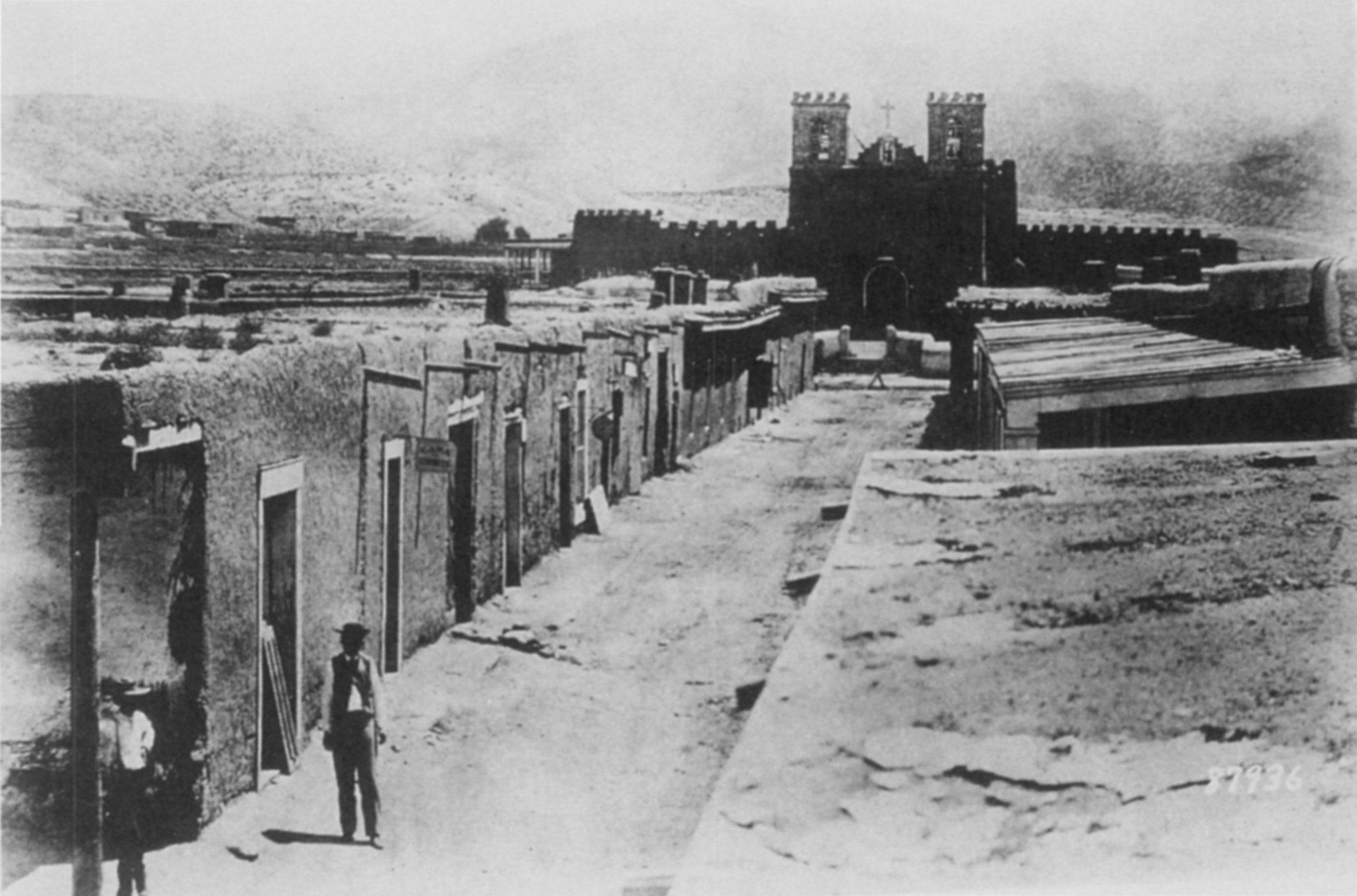

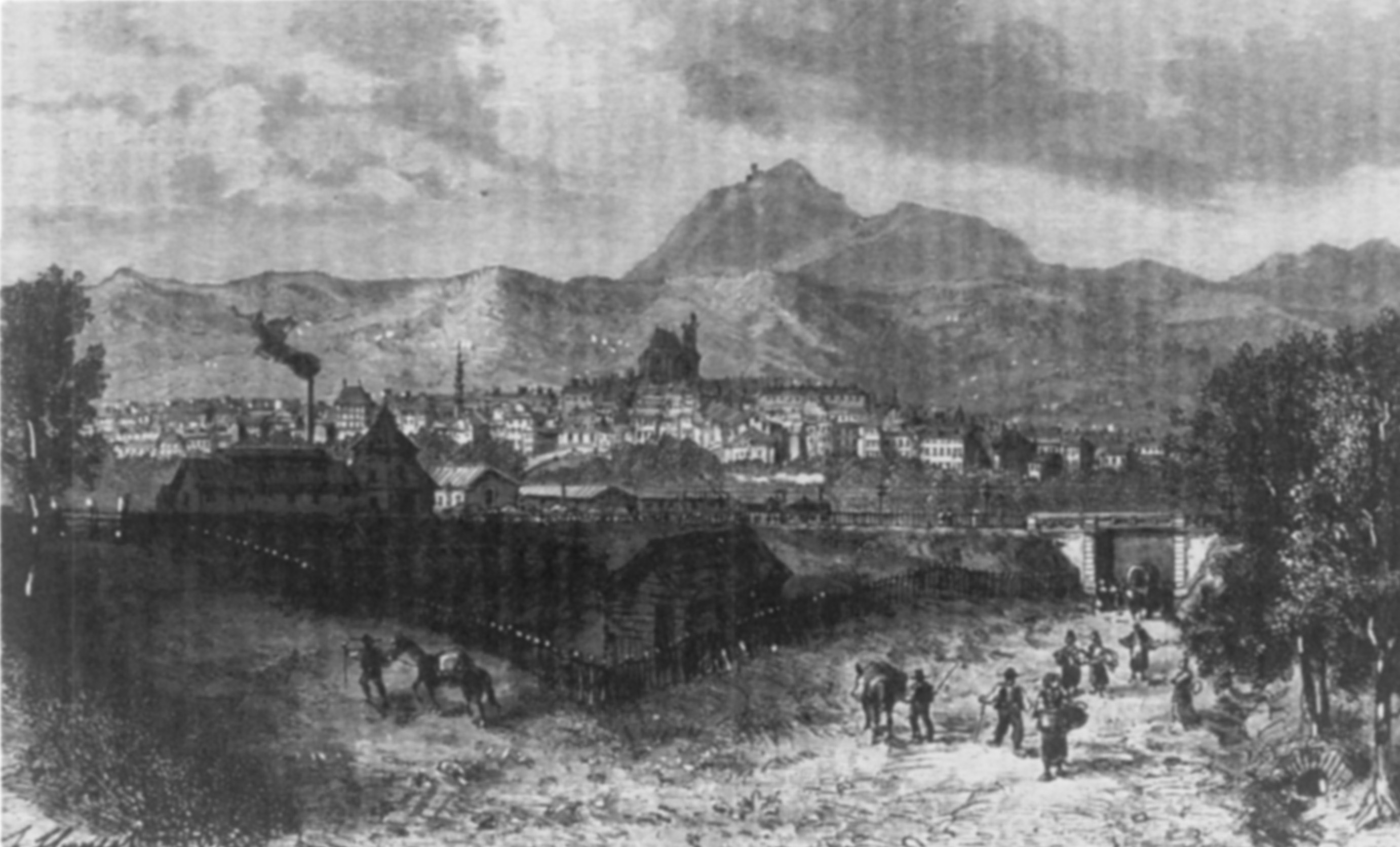

It was nearly a year after he had embarked upon the Mississippi that the young Bishop, at about the sunset hour of a summer afternoon, at last beheld the old settlement toward which he had been journeying so long: The wagon train had been going all day through a greasewood plain, when late in the afternoon the teamsters began shouting that over yonder was the Villa. Across the level, Father Latour could distinguish low brown shapes, like earthworks, lying at the base of wrinkled green mountains with bare tops,— wave-like mountains, resembling billows beaten up from a flat sea by a heavy gale; and their green was of two colors— aspen and evergreen, not intermingled but lying in solid areas of light and dark.

As the wagons went forward and the sun sank lower, a sweep of red carnelian-coloured hills lying at the foot of the mountains came into view; they curved like two arms about a depression in the plain; and in that depression was Santa Fé, at last! A thin, wavering adobe town…a green plaza…at one end a church with two earthen towers that rose high above the flatness. The long main street began at the church, the town seemed to flow from it like a stream from a spring. The church towers, and all the low adobe houses, were rose colour in that light,— a little darker in tone than the amphitheatre of red hills behind; and periodically the plumes of poplars flashed like gracious accent marks,— inclining and recovering themselves in the wind.

The young Bishop was not alone in the exaltation of that hour; beside him rode Father Joseph Vaillant, his boyhood friend, who had made this long pilgrimage with him and shared his dangers. The two rode into Santa Fé together, claiming it for the glory of God.

How, then, had Father Latour come to be here in the sand-hills, many miles from his seat, unattended, far out of his way and with no knowledge of how to get back to it?

He had been warned that there were many trails leading off the Rio Grande road, and that a stranger might easily mistake his way. For the first few days he had been cautious and watchful. Then he must have grown careless and turned into some purely local trail. When he realized that he was astray, his canteen was already empty and his horses seemed too exhausted to retrace their steps. He had persevered in this sandy track, which grew ever fainter, reasoning that it must lead somewhere.

All at once Father Latour thought he felt a change in the body of his mare. She lifted her head for the first time in a long while, and seemed to redistribute her weight upon her legs. The pack-mule behaved in a similar manner, and both quickened their pace. Was it possible they scented water?

Nearly an hour went by, and then, winding between two hills that were like all the hundreds they had passed, the two beasts whinnied simultaneously. Below them, in the midst of that wavy ocean of sand, was a green thread of verdure and a running stream. This ribbon in the desert seemed no wider than a man could throw a stone,— and it was greener than anything Latour had ever seen, even in his own greenest corner of the Old World. But for the quivering of the hide on his mare's neck and shoulders, he might have thought this a vision, a delusion of thirst.

Running water, clover fields, cottonwoods, locust trees, little adobe houses with brilliant gardens, a boy driving a flock of white goats toward the stream,— that was what the young Bishop saw.

A few moments later, when he was struggling with his horses, trying to keep them from over drinking, a young girl with a black shawl over her head came running toward him. He thought he had never seen a kindlier face. Her greeting was that of a Christian.

"Ave María Purísima, Señor. Whence do you come?"

"Blessed child," he replied in Spanish, "I am a priest who has lost his way. I am famished for water."

"A priest? " she cried, "that is not possible! Yet I look at you, and it is true. Such a thing has never happened to us before; it must be in answer to my father's prayers. Run, Pedro, and tell father and Salvatore."

2

HIDDEN WATER

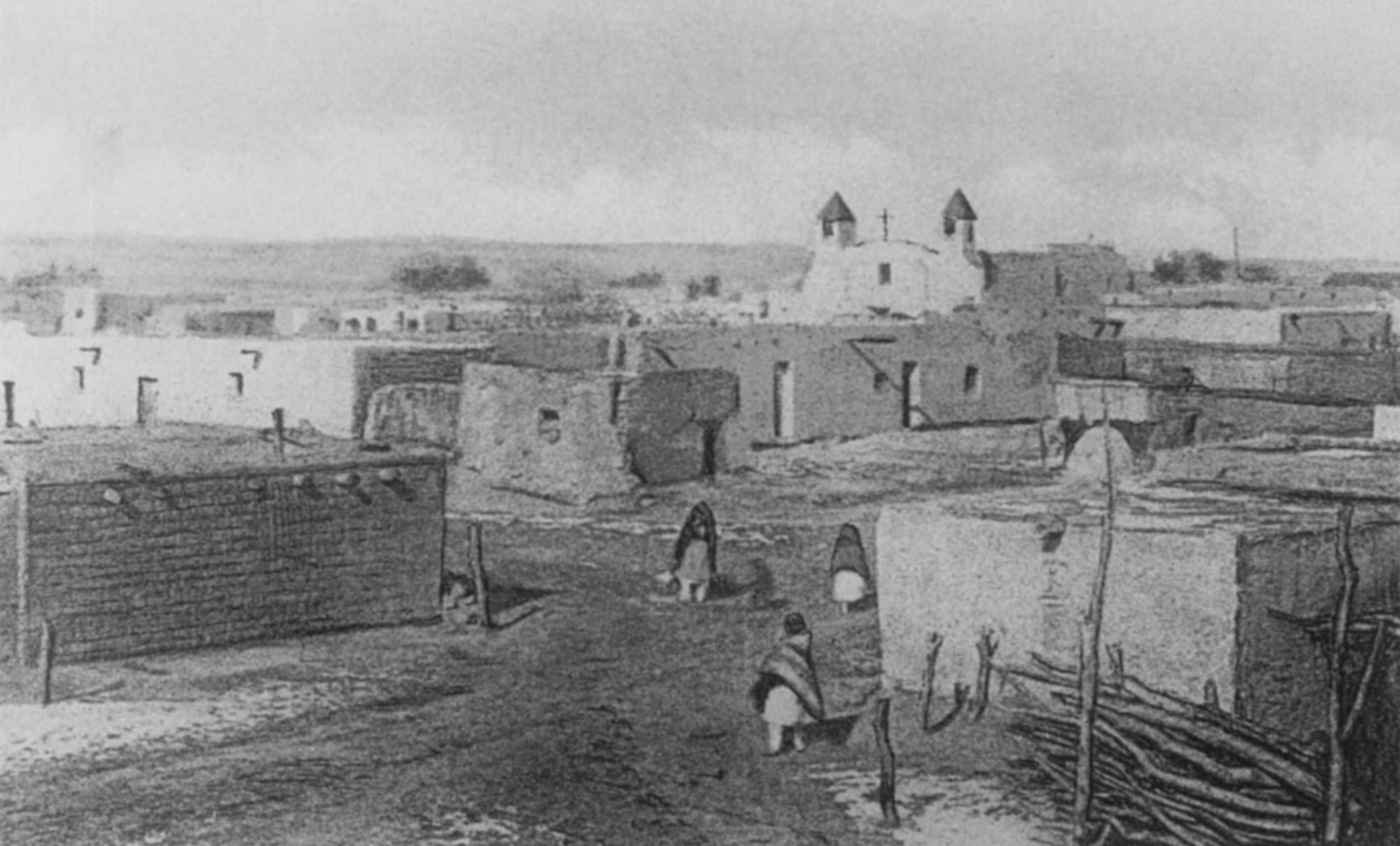

An hour later, as darkness came over the sand-hills, the young Bishop was seated at supper in the mother-house of this Mexican settlement— which, he learned, was appropriately called Ague Secreta, Hidden Water. At the table with him were his host, an old man called Benito, the oldest son, and two grandsons. The old man was a widower, and his daughter, Josepha, the girl who had run to meet the Bishop at the stream, was his housekeeper. Their supper was a pot of frijoles cooked with meat, bread and goat's milk, fresh cheese and ripe apples.

From the moment he entered this room with its thick whitewashed adobe walls, Father Latour had felt a kind of peace about it. In its bareness and simplicity there was something comely, as there was about the serious girl who had placed their food before them and who now stood in the shadows against the wall, her eager eyes fixed upon his face. He found himself very much at home with the four dark-headed men who sat beside him in the candlelight. Their manners were gentle, their voices low and agreeable. When he said grace before meat, the men had knelt on the floor beside the table. The grandfather declared that the Blessed Virgin must have led the Bishop from his path and brought him here to baptize the children and to sanctify the marriages. Their settlement was little known, he said. They had no papers for their land and were afraid the Americans might take it away from them. There was no one in their settlement who could read or write. Salvatore, his oldest son, had gone all the way to Albuquerque to find a wife, and had married there. But the priest had charged him twenty pesos, and that was half of all he had saved to buy furniture and glass windows for his house. His brothers and cousins, discouraged by his experience, had taken wives without the marriage sacrament.

In answer to the Bishop's questions, they told him the simple story of their lives. They had here all they needed to make them happy. They spun and wove from the fleece of their flocks, raised their own corn and wheat and tobacco, dried their plums and apricots for winter. Once a year the boys took the grain up to Albuquerque to have it ground, and bought such luxuries as sugar and coffee. They had bees, and when sugar was high they sweetened with honey. Benito did not know in what year his grandfather had settled here, coming from Chihuahua with all his goods in ox-carts. "But it was soon after the time when the French killed their king. My grandfather had heard talk of that before he left home, and used to tell us boys about it when he was an old man."

"Perhaps you have guessed that I am a Frenchman," said Father Latour.

No, they had not, but they felt sure he was not an American. José, the elder grandson, had been watching the visitor uncertainly. He was a handsome boy, with a triangle of black hair hanging over his rather sullen eyes. He now spoke for the first time.

"They say at Albuquerque that now we are all Americans, but that is not true, Padre. I will never be an American. They are infidels."

"Not all, my son. I have lived among Americans in the north for ten years, and I found many devout Catholics."

The young man shook his head. "They destroyed our churches when they were fighting us, and stabled their horses in them. And now they will take our religion away from us. We want our own ways and our own religion."

Father Latour began to tell them about his friendly relations with Protestants in Ohio, but they had not room in their minds for two ideas; there was one Church, and the rest of the world was infidel. One thing they could understand; that he had here in his saddlebags his vestments, the altar stone, and all the equipment for celebrating the Mass; and that tomorrow morning, after Mass, he would hear confessions, baptize, and sanctify marriages.

After supper Father Latour took up a candle and began to examine the holy images on the shelf over the fire-place. The wooden figures of the saints, found in even the poorest Mexican houses, always interested him. He had never yet seen two alike. These over Benito's fire-place had come in the ox-carts from Chihuahua nearly sixty years ago. They had been carved by some devout soul, and brightly painted, though the colours had softened with time, and they were dressed in cloth, like dolls. They were much more to his taste than the factory-made plaster images in his mission churches in Ohio— more like the homely stone carvings on the front of old parish churches in Auvergne. The wooden Virgin was a sorrowing mother indeed, —long and stiff and severe, very long from the neck to the waist, even longer from waist to feet, like some of the rigid mosaics of the Eastern Church. She was dressed in black, with a white apron, and a black rebozo over her head, like a Mexican woman of the poor. At her right was St. Joseph, and at her left a fierce little equestrian figure, a saint wearing the costume of a Mexican ranchero, velvet trousers richly embroidered and wide at the ankle, velvet jacket and silk shirt, and a highcrowned, broad-brimmed Mexican sombrero. He was attached to his fat horse by a wooden pivot driven through the saddle.

The younger grandson saw the priest's interest in this figure. "That," he said, "is my name saint, Santiago."

"Oh, yes; Santiago. He was a missionary, like me. In our country we call him St. Jacques, and he carries a staff and a wallet— but here he would need a horse, surely."

The boy looked at him in surprise. "But he is the saint of horses. Isn't he that in your country?"

The Bishop shook his head. "No. I know nothing about that. How is he the saint of horses?"

A little later, after his devotions, the young Bishop lay down in Benito's deep feather-bed, thinking how different was this night from his anticipation of it. He had expected to make a dry camp in the wilderness, and to sleep under a juniper tree, like the Prophet, tormented by thirst. But here he lay in comfort and safety, with love for his fellow creatures flowing like peace about his heart. If Father Valliant were here, he would say, "A miracle"; that the Holy Mother, to whom he had addressed himself before the cruciform tree, had led him hither. And it was a miracle, Father Latour knew that. But his dear Joseph must always have the miracle very direct and spectacular, not with Nature, but against it. He would almost be able to tell the colour of the mantle Our Lady wore when She took the mare by the bridle back yonder among the junipers and led her out of the pathless sand-hills, as the angel led the ass on the Flight into Egypt.

***

In the late afternoon of the following day the Bishop was walking alone along the banks of the life-giving stream, reviewing in his mind the events of the morning. Benito and his daughter had made an altar before the sorrowful wooden Virgin, and placed upon it candles and flowers. Every soul in the village, except Salvatore's sick wife, had come to the Mass. He had performed marriages and baptisms and heard confessions and confirmed until noon. Then came the christening feast. José had killed a kid the night before, and immediately after her confirmation Josepha slipped away to help her sisters-in-law roast it. When Father Latour asked her to give him his portion without chili, the girl inquired whether it was more pious to eat it like that. He hastened to explain that Frenchmen, as a rule, do not like high seasoning, lest she should hereafter deprive herself of her favourite condiment.

After the feast the sleepy children were taken home, the men gathered in the plaza to smoke under the great cottonwood trees. The Bishop, feeling a need of solitude, had gone forth to walk, firmly refusing an escort. On his way he passed the earthen thrashing-floor, where these people beat out their grain and winnowed it in the wind, like the Children of Israel. He heard a frantic bleating behind him, and was overtaken by Pedro with the great flock of goats, indignant at their day's confinement, and wild to be in the fringe of pasture along the hills. They leaped the stream like arrows speeding from the bow, and regarded the Bishop as they passed him with their mocking, humanly intelligent smile. The young bucks were light and elegant in figure, with their pointed chins and polished tilted horns. There was great variety in their faces, but in nearly all something supercilious and sardonic. The angoras had long silky hair of a dazzling whiteness. As they leaped through the sunlight they brought to mind the chapter in the Apocalypse, about the whiteness of them that were washed in the blood of the Lamb. The young Bishop smiled at his mixed theology. But though the goat had always been the symbol of pagan lewdness, he told himself that their fleece had warmed many a good Christian, and their rich milk nourished sickly children.

About a mile above the village he came upon the water-head, a spring overhung by the sharp-leafed variety of cottonwood called water willow. All about it crowded the oven-shaped hills,— nothing to hint of water until it rose miraculously out of the parched and thirsty sea of sand. Some subterranean stream found an outlet here, was released from darkness. The result was grass and trees and flowers and human life; household order and hearths from which the smoke of burning piñon logs rose like incense to Heaven.

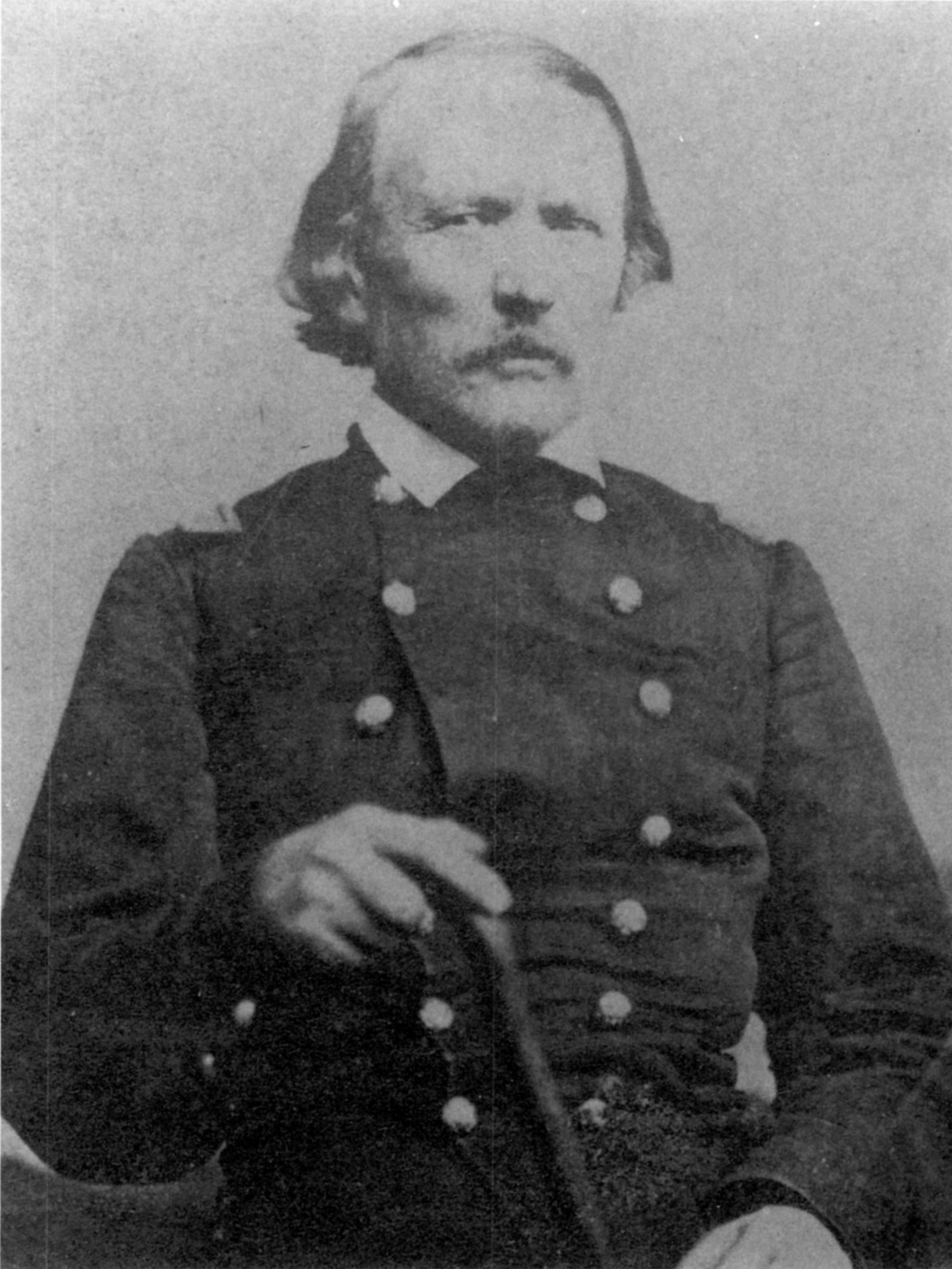

The Bishop sat a long time by the spring, while the declining sun poured its beautifying light over those low, rose-tinted houses and bright gardens. The old grandfather had shown him arrow-heads and corroded medals, and a sword hilt, evidently Spanish, that he had found in the earth near the water-head. This spot had been a refuge for humanity long before these Mexicans had come upon it. It was older than history, like those well-heads in his own country where the Roman settlers had set up the image of a river goddess, and later the Christian priests had planted a cross. This settlement was his Bishopric in miniature; hundreds of square miles of thirsty desert, then a spring, a village, old men trying to remember their catechism to teach their grand-children. The Faith planted by the Spanish friars and watered with their blood was not dead; it awaited only the toil of the husbandman. He was not troubled about the revolt in Santa Fé, or the powerful old native priest who led it—Father Martínez, of Taos, who had ridden over from his parish expressly to receive the new Vicar and to drive him away. He was rather terrifying, that old priest, with his big head, violent Spanish face, and shoulders like a buffalo; but the day of his tyranny was almost over.

3

THE BISHOP CHEZ LUI

It was the late afternoon of Christmas Day, and the Bishop sat at his desk writing letters. Since his return to Santa Fé his official correspondence had been heavy; but the closely-written sheets over which he bent with a thoughtful smile were not to go to Monsignori, or to Archbishops, or to the heads of religious houses, —but to France, to Auvergne, to his own little town; to a certain grey, winding street, paved with cobbles and shaded by tall chestnuts on which, even to-day, some few brown leaves would be clinging, or dropping one by one, to be caught in the cold green ivy on the walls.

The Bishop had returned from his long horseback trip into Mexico only nine days ago. At Durango the old Mexican prelate there had, after some delay, delivered to him the documents that defined his Vicarate, and Father Latour rode back the fifteen hundred miles to Santa Fé through the sunny days of early winter. On his arrival he found amity instead of enmity awaiting him. Father Valliant had already endeared himself to the people. The Mexican priest who was in charge of the pro-cathedral had gracefully retired—gone to visit his family in Old Mexico, and carried his effects along with him. Father Valliant had taken possession of the priest's house, and with the help of carpenters and the Mexican women of the parish had put it in order. The Yankee traders and the military Commandant at Fort Marcy had sent generous contributions of bedding and blankets and odd pieces of furniture.

The Episcopal residence was an old adobe house, much out of repair, but with possibilities of comfort. Father Latour had chosen for his study a room at one end of the wing. There he sat, as this afternoon of Christmas Day faded into evening. It was a long room of an agreeable shape. The thick clay walls had been finished on the inside by the deft palms of Indian women, ,and had that irregular and intimate quality of things made entirely by the human hand. There was a reassuring solidity and depth about those walls, rounded at door-sills and window-sills, rounded in wide wings about the corner fire-place. The interior had been newly whitewashed in the Bishop's absence, and the flicker of the fire threw a rosy glow over the wavy surfaces, never quite evenly flat, never a dead white, for the ruddy colour of the clay underneath gave a warm tone to the lime wash. The ceiling was made of heavy cedar beams, overlaid by aspen saplings, all of one size, lying close together like the ribs in corduroy and clad in their ruddy inner skins. The earth floor was covered with thick Indian blankets; two blankets, very old, and beautiful in design and colour, were hung on the walls like tapestries.

On either side of the fire-place plastered recesses were let into the wall. In one, narrow and arched, stood the Bishop's crucifix. The other was square, with a carved wooden door, like a grill, and within it lay a few rare and beautiful books. The rest of the Bishop's library was on open shelves at one end of the room.

The furniture of the house Father Valliant had bought from the departed Mexican priest. It was heavy and somewhat clumsy, but not unsightly. All the wood used in making tables and bedsteads was hewn from tree boles with the ax or hatchet. Even the thick planks on which the Bishop's theological books rested were ax-dressed. There was not at that time a turning-lathe or a saw-mill in all northern New Mexico. The native carpenters whittled out chair rungs and table legs, and fitted them together with wooden pins instead of iron nails. Wooden chests were used in place of dressers with drawers, and sometimes these were beautifully carved, or covered with decorated leather. The desk at which the Bishop sat writing was an importation, a walnut "secretary" of American make (sent down by one of the officers of the Fort at Father Vaillant's suggestion). His silver candlesticks he had brought from France long ago. They were given to him by a beloved aunt when he was ordained.

The young Bishop's pen flew over the paper, leaving a trail of fine, finished French script behind, in violet ink.

"My new study, dear brother, as I write, is full of the delicious fragrance of the piñon logs burning in my fire-place. (We use this kind of cedar-wood altogether for fuel, and it is highly aromatic, yet delicate. At our meanest tasks we have a perpetual odour of incense about us.) I wish that you, and my dear sister, could look in upon this scene of comfort and peace. We missionaries wear a frock-coat and wide-brimmed hat all day, you know, and look like American traders. What a pleasure to come home at night and put on my old cassock! I feel more like a priest then—for so much of the day I must be a 'business man'!—and, for some reason, more like a Frenchman. All day I am an American in speech and thought—yes, in heart, too. The kindness of the American traders, and especially of the military officers at the Fort, commands more than a superficial loyalty. I mean to help the officers at their task here. I can assist them more than they realize. The Church can do more than the Fort to make these poor Mexicans 'good Americans.' And it is for the people's good; there is no other way in which they can better their condition.

"But this is not the day to write you of my duties or my purposes. To-night we are exiles, happy ones, thinking of home. Father Joseph has sent away our Mexican woman,—he will make a good cook of her in time, but to-night he is preparing our Christmas dinner himself. I had thought he would be worn out to-day, for he has been conducting a Novena of High Masses, as is the custom here before Christmas. After the Novena, and the midnight Mass last night, I supposed he would be willing to rest to-day; but not a bit of it. You know his motto, 'Rest in action.' I brought him a bottle of olive-oil on my horse all the way from Durango (I say 'olive-oil,' because here 'oil' means something to grease the wheels of wagons!), and he is making some sort of cooked salad. We have no green vegetables here in winter, and no one seems ever to have heard of that blessed plant, the lettuce. Joseph finds it hard to do without salad-oil, he always had it in Ohio, though it was a great extravagance. He has been in the kitchen all afternoon. There is only an open fire-place for cooking, and an earthen roasting-oven out in the courtyard. But he has never failed me in anything yet; and I think I can promise you that to-night two Frenchmen will sit down to a good dinner and drink your health."

The Bishop laid down his pen and lit his two candles with a splinter from the fire, then stood dusting his fingers by the deep-set window, looking out at the pale blue darkening sky. The evening-star hung above the amber afterglow, so soft, so brilliant that she seemed to bathe in her own silver light. Ave Maris Stella, the song which one of his friends at the Seminary used to intone so beautifully; humming it softly he returned to his desk and was just dipping his pen in the ink when the door opened, and a voice said,

"Monseigneur est servi! Alors, Jean, veux-tu ap porter les bougies."

The Bishop carried the candles into the dining-room, where the table was laid and Father Valliant was changing his cook's apron for his cassock. Crimson from standing over an open fire, his rugged face was even homelier than usual—though one of the first things a stranger decided upon meeting Father Joseph was that the Lord had made few uglier men. He was short, skinny, bow-legged from a life on horseback, and his countenance had little to recommend it but kindliness and vivacity. He looked old, though he was then about forty. His skin was hardened and seamed by exposure to weather in a bitter climate, his neck scrawny and wrinkled like an old man's. A bold, blunt-tipped nose, positive chin, a very large mouth,—the lips thick and succulent but never loose, never relaxed, always stiffened by effort or working with excitement. His hair, sunburned to the shade of dry hay, had originally been tow-coloured; "Blanchet" ("Whitey") he was always called at the Seminary. Even his eyes were near-sighted, and of such a pale, watery blue as to be unimpressive. There was certainly nothing in his outer case to suggest the fierceness and fortitude and fire of the man, and yet even the thick-blooded Mexican half-breeds knew his quality at once. If the Bishop returned to find Santa Fé friendly to him, it was because everybody believed in Father Vaillant— homely, real, persistent, with the driving power of a dozen men in his poorly built body.

On coming into the dining-room, Bishop Latour placed his candlesticks over the fire-place, since there were already six upon the table, illuminating the brown soup-pot. After they had stood for a moment in prayer, Father Joseph lifted the cover and ladled the soup into the plates, a dark onion soup with croutons. The Bishop tasted it critically and smiled at his companion. After the spoon had travelled to his lips a few times, he put it down and leaning back in his chair remarked,

"Think of it, Blanchet; in all this vast country between the Mississippi and the Pacific Ocean, there is probably not another human being who could make a soup like this."

"Not unless he is a Frenchman," said Father Joseph. He had tucked a napkin over the front of his cassock and was losing no time in reflection.

"I am not deprecating your individual talent, Joseph," the Bishop continued, "but, when one thinks of it, a soup like this is not the work of one man. It is the result of a constantly refined tradition. There are nearly a thousand years of history in this soup."

Father Joseph frowned intently at the earthen pot in the middle of the table. His pale, near-sighted eyes had always the look of peering into distance. "C'est ça, c'est vrai," he murmured. "But how," he exclaimed as he filled the Bishop's plate again, "how can a man make a proper soup without leeks, that king of vegetables? We cannot go on eating onions for ever."

After carrying away the soupière, he brought in the roast chicken and pommes sautées. "And salad, Jean," he continued as he began to carve. "Are we to eat dried beans and roots for the rest of our lives? Surely we must find time to make a garden. Ah, my garden at Sandusky! And you could snatch me away from it! You will admit that you never ate better lettuces in France. And my vineyard; a natural habitat for the vine, that. I tell you, the shores of Lake Erie will be covered with vineyards one day. I envy the man who is drinking my wine. Ah well, that is a missionary's life; to plant where another shall reap."

As this was Christmas Day, the two friends were speaking in their native tongue. For years they had made it a practice to speak English together, except upon very special occasions, and of late they conversed in Spanish, in which they both needed to gain fluency.

"And yet sometimes you used to chafe a little at your dear Sandusky and its comforts," the Bishop reminded him—" to say that you would end a home-staying parish priest, after all."

"Of course, one wants to eat one's cake and have it, as they say in Ohio. But no farther, Jean. This is far enough. Do not drag me any farther." Father Joseph began gently to coax the cork from a bottle of red wine with his fingers. "This I begged for your dinner at the hacienda where I went to baptize the baby on St. Thomas's Day. It is not easy to separate these rich Mexicans from their French wine. They know its worth." He poured a few drops and tried it. "A slight taste of the cork; they do not know how to keep it properly. However, it is quite good enough for missionaries."

"You ask me not to drag you any farther, Joseph. I wish," Bishop Latour leaned back in his chair and locked his hands together beneath his chin, I wish I knew how far this is! Does anyone know the extent of this diocese, or of this territory? The Commandant at the Fort seems as much in the dark as I. He says I can get some information from the scout, Kit Carson, who lives at Taos."

"Don't begin worrying about the diocese, Jean. For the present, Santa Fé is the diocese. Establish order at home. Tomorrow I will have a reckoning with the churchwardens, who allowed that band of drunken cowboys to come in to the midnight Mass and defile the font. There is enough to do here. Festina lente. I have made a resolve not to go more than three days' journey from Santa Fé for one year."

The Bishop smiled and shook his head. "And when you were at the Seminary, you made a resolve to lead a life of contemplation."

A light leaped into Father Joseph's homely face. "I have not yet renounced that hope. One day you will release me, and I will return to some religious house in France and end my days in devotion to the Holy Mother. For the time being, it is my destiny to serve Her in action. But this is far enough, Jean."

The Bishop again shook his head and murmured, "Who knows how far?"

The wiry little priest whose life was to be a succession of mountain ranges, pathless deserts, yawning canyons and swollen rivers, who was to carry the Cross into territories yet unknown and unnamed, who would wear down mules and horses and scouts and stage-drivers, to-night looked apprehensively at his superior and repeated, "No more, Jean. This is far enough." Then making haste to change the subject, he said briskly, "A bean salad was the best I could do for you; but with onion, and just a suspicion of salt pork, it is not so bad."

Over the compote of dried plums they fell to talking of the great yellow ones that grew in the old Latour garden at home. Their thoughts met in that tilted cobble street, winding down a hill, with the uneven garden walls and tall horse-chestnuts on either side; a lonely street after nightfall, with soft street lamps shaped like lanterns at the darkest turnings. At the end of it was the church where the Bishop made his first Communion, with a grove of flat-cut plane trees in front, under which the market was held on Tuesdays and Fridays.

While they lingered over these memories—an indulgence they seldom permitted themselves— the two missionaries were startled by a volley of rifle-shots and blood-curdling yells without, and the galloping of horses. The Bishop half rose, but Father Joseph reassured him with a shrug.

"Do not discompose yourself. The same thing happened here on the eve of All Souls' Day. A band of drunken cowboys, like those who came into the church last night, go out to the pueblo and get the Tesuque Indian boys drunk, and then they ride in to serenade the soldiers at the Fort in this manner."

4

A BELL AND A MIRACLE

On the morning after the Bishop's return from Durango, after his first night in his Episcopal residence, he had a pleasant awakening from sleep. He had ridden into the courtyard after nightfall, having changed horses at a rancho and pushed on nearly sixty miles in order to reach home. Consequently he slept late the next morning— did not awaken until six o'clock, when he heard the Angelus ringing. He recovered consciousness slowly, unwilling to let go of a pleasing delusion that he was in Rome. Still half believing that he was lodged near St. John Lateran, he yet heard every stroke of the Ave Maria bell, marvelling to hear it rung correctly (nine quick strokes in all, divided into threes, with an interval between); and from a bell with beautiful tone. Full, clear, with something bland and suave, each note floated through the air like a globe of silver. Before the nine strokes were done Rome faded, and behind it he sensed something Eastern, with palm trees,— Jerusalem, perhaps, though he had never been there. Keeping his eyes closed, he cherished for a moment this sudden, pervasive sense of the East. Once before he had been carried out of the body thus to a place far away. It had happened in a street in New Orleans. He had turned a corner and come upon an old woman with a basket of yellow flowers; sprays of yellow sending out a honey-sweet perfume. Mimosa— but before he could think of the name he was overcome by a feeling of place, was dropped, cassock and all, into a garden in the south of France where he had been sent one winter in his childhood to recover from an illness. And now this silvery bell note had carried him farther and faster than sound could travel.

When he joined Father Valliant at coffee, that impetuous man who could never keep a secret asked him anxiously whether he had heard anything.

"I thought I heard the Angelus, Father Joseph, but my reason tells me that only a long sea voyage could bring me within sound of such a bell."

"Not at all," said Father Joseph briskly. "I found that remarkable bell here, in the basement of old San Miguel. They tell me it has been here a hundred years or more. There is no church tower in the place strong enough to hold it—it is very thick and must weigh close upon eight hundred pounds. But I had a scaffolding built in the churchyard, and with the help of oxen we raised it and got it swung on cross-beams. I taught a Mexican boy to ring it properly against your return."

"But how could it have come here? It is Spanish, I suppose?"

"Yes, the inscription is in Spanish, to St. Joseph, and the date is 1356. It must have been brought up from Mexico City in an ox-cart. A heroic undertaking, certainly. Nobody knows where it was cast. But they do tell a story about it: that it was pledged to St. Joseph in the wars with the Moors, and that the people of some besieged city brought all their plate and silver and gold ornaments and threw them in with the baser metals. There is certainly a good deal of silver in the bell, nothing else would account for its tone."

Father Latour reflected. "And the silver of the Spaniards was really Moorish, was it not? If not actually of Moorish make, copied from their design. The Spaniards knew nothing about working silver except as they learned it from the Moors."

"What are you doing, Jean? Trying to make my bell out an infidel? " Father Joseph asked impatiently.

The Bishop smiled. "I am trying to account for the fact that when I heard it this morning it struck me at once as something oriental. A learned Scotch Jesuit in Montreal told me that our first bells, and the introduction of the bell in the service all over Europe, originally came from the East. He said the Templars brought the Angelus back from the Crusades, and it is really an adaptation of a Moslem custom."

Father Valliant sniffed. "I notice that scholars always manage to dig out something belittling," he complained.

"Belittling? I should say the reverse. I am glad to think there is Moorish silver in your bell. When we first came here, the one good workman we found in Santa Fé was a silversmith. The Spaniards handed on their skill to the Mexicans, and the Mexicans have taught the Navajos to work silver; but it all came from the Moors."

"I am no scholar, as you know," said Father Vaillant rising. "And this morning we have many practical affairs to occupy us. I have promised that you will give an audience to a good old man, a native priest from the Indian mission at Santa Clara, who is returning from Mexico. He has just been on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Guadaloupe and has been much edified. He would like to tell you the story of his experience. It seems that ever since he was ordained he has desired to visit the shrine. During your absence I have found how particularly precious is that shrine to all Catholics in New Mexico. They regard it as the one absolutely authenticated appearance of the Blessed Virgin in the New World, and a witness of Her affection for Her Church on this continent."

The Bishop went into his study, and Father Valliant brought in Padre Escolastico Herrera, a man of nearly seventy, who had been forty years in the ministry, and had just accomplished the pious desire of a lifetime. His mind was still full of the sweetness of his late experience. He was so rapt that nothing else interested him. He asked anxiously whether perhaps the Bishop would have more leisure to attend to him later in the day. But Father Latour placed a chair for him and told him to proceed.

The old man thanked him for the privilege of being seated. Leaning forward, with his hands locked between his knees, he told the whole story of the miraculous appearance, both because it was so dear to his heart, and because he was sure that no "American" Bishop would have heard of the occurrence as it was, though at Rome all the details were well known and two Popes had sent gifts to the shrine.

On Saturday, December 9th, in the year 1531, a poor neophyte of the monastery of St. James was hurrying down Tapeyac hill to attend Mass in the City of Mexico. His name was Juan Diego and he was fifty-five years old. When he was half way down the hill a light shone in his path, and the Mother of God appeared to him as a young woman of great beauty, clad in blue and gold. She greeted him by name and said :

"Juan, seek out thy Bishop and bid him build a church in my honour on the spot where I now stand. Go then, and I will bide here and await thy return."

Brother Juan ran into the City and straight to the Bishop's palace, where he reported the matter. The Bishop was Zumarraga, a Spaniard. He questioned the monk severely and told him he should have required a sign of the Lady to assure him that she was indeed the Mother of God and not some evil spirit. He dismissed the poor brother harshly and set an attendant to watch his actions.

Juan went forth very downcast and repaired to the house of his uncle, Bernardino, who was sick of a fever. The two succeeding days he spent in caring for this aged man who seemed at the point of death. Because of the Bishop's reproof he had fallen into doubt, and did not return to the spot where the Lady said She would await him. On Tuesday he left the City to go back to his monastery to fetch medicines for Bernardino, but he avoided the place where he had seen the vision and went by another way.

Again he saw a light in his path and the Virgin appeared to him as before, saying, "Juan, why goest thou by this way?"

Weeping, he told Her that the Bishop had distrusted his report, and that he had been employed in caring for his uncle, who was sick unto death. The Lady spoke to him with all comfort, telling him that his uncle would be healed within the hour, and that he should return to Bishop Zumarraga and bid him build a church where She had first appeared to him. It must be called the shrine of Our Lady of Guadaloupe, after Her dear shrine of that name in Spain. When Brother Juan replied to Her that the Bishop required a sign, She said: "Go up on the rocks yonder, and gather roses."

Though it was December and not the season for roses, he ran up among the rocks and found such roses as he had never seen before. He gathered them until he had filled his tilma. The tilma was a mantle worn only by the very poor, —a wretched garment loosely woven of coarse vegetable fibre and sewn down the middle. When he returned to the apparition, She bent over the flowers and took pains to arrange them, then closed the ends of the tilma together and said to him:

"Go now, and do not open your mantle until you open it before your Bishop."

Juan sped into the City and gained admission to the Bishop, who was in council with his Vicar.

"Your Grace," he said, " the Blessed Lady who appeared to me has sent you these roses for a sign."

At this he held up one end of his tilma and let the roses fall in profusion to the floor. To his astonishment, Bishop Zumarraga and his Vicar instantly fell upon their knees among the flowers. On the inside of his poor mantle was a painting of the Blessed Virgin, in robes of blue and rose and gold, exactly as She had appeared to him upon the hill-side.

A shrine was built to contain this miraculous portrait, which since that day has been the goal of countless pilgrimages and has performed many miracles.

Of this picture Padre Escolástico had much to say: he affirmed that it was of marvellous beauty, rich with gold, and the colours as pure and delicate as the tints of early morning. Many painters had visited the shrine and marvelled that paint could be laid at all upon such poor and coarse material. In the ordinary way of nature, the flimsy mantle would have fallen to pieces long ago. The Padre modestly presented Bishop Latour and Father Joseph with little medals he had brought from the shrine; on one side a relief of the miraculous portrait, on the other an inscription: Non fecit taliter omni nationi. (She hath not dealt so with any nation.)

Father Vaillant was deeply stirred by the priest's recital, and after the old man had gone he declared to the Bishop that he meant himself to make a pilgrimage to this shrine at the earliest opportunity.

"What a priceless thing for the poor converts of a savage country!" he exclaimed, wiping his glasses, which were clouded by his strong feeling. "All these poor Catholics who have been so long without instruction have at least the reassurance of that visitation. It is a household word with them that their Blessed Mother revealed Herself in their own country, to a poor convert. Doctrine is well enough for the wise, Jean; but the miracle is something we can hold in our hands and love."

Father Valliant began pacing restlessly up and down as he spoke, and the Bishop watched him, musing. It was just this in his friend that was dear to him. "Where there is great love there are always miracles," he said at length. "One might almost say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love. I do not see you as you really are, Joseph; I see you through my affection for you. The Miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming suddenly near to us from afar off, but upon our perceptions being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always."

Book Two

MISSIONARY JOURNEYS

1

THE WHITE MULES

In mid-March, Father Valliant was on the road, returning from a missionary journey to Albuquerque. He was to stop at the rancho of a rich Mexican, Manuel Lujon, to marry his men and maid servants who were living in concubinage, and to baptize the children. There he would spend the night. To-morrow or the day after he would go on to Santa Fé, halting by the way at the Indian pueblo of Santo Domingo to hold service. There was a fine old mission church at Santo Domingo, but the Indians were of a haughty and suspicious disposition. He had said Mass there on his way to Albuquerque, nearly a week ago. By dint of canvassing from house to house, and offering medals and religious colour prints to all who came to church, he had got together a consider-able congregation. It was a large and prosperous pueblo, set among clean sand-hills, with its rich irrigated farm lands lying just below, in the valley of the Rio Grande. His congregation was quiet, dignified, attentive. They sat on the earth floor, wrapped in their best blankets, repose in every line of their strong, stubborn backs. He harangued them in such Spanish as he could command, and they listened with respect. But bring their children to be baptized, they would not. The Spaniards had treated them very badly long ago, and they had been meditating upon their grievance for many generations. Father Valliant had not baptized one infant there, but he meant to stop to-morrow and try again. Then back to his Bishop, provided he could get his horse up La Bajada Hill.

He had bought his horse from a Yankee trader and had been woefully deceived. One week's journey of from twenty to thirty miles a day had shown the beast up for a wind-broken wreck. Father Vaillant's mind was full of material cares as he approached Manuel Lujon's place beyond Bernalillo. The rancho was like a little town, with all its stables, corrals, and stake fences. The casa grande was long and low, with glass windows and bright blue doors, a portale running its full length, supported by blue posts. Under this portale the adobe wall was hung with bridles, saddles, great boots and spurs, guns and saddle blankets, strings of red peppers, fox skins, And the skins of two great rattlesnakes.

When Father Vaillant rode in through the gate-way, children came running from every direction, some with no clothing but a little shirt, and women with no shawls over their black hair came running after the children. They all disappeared when Manuel Lujon walked out of the great house, hat in hand, smiling and hospitable. He was a man of thirty-five, settled in figure and somewhat full under the chin. He greeted the priest in the name of God and put out a hand to help him alight, but Father Vaillant sprang quickly to the ground.

"God be with you, Manuel, and with your house. But where are those who are to be married?"

"The men are all in the field, Padre. There is no hurry. A little wine, a little bread, coffee, repose— and then the ceremonies."

"A little wine, very willingly, and bread, too. But not until afterward. I meant to catch you all at dinner, but I am two hours late because my horse is bad. Have someone bring in my saddle-bags, and I will put on my vestments. Send out to the fields for your men, Señor Lujon. A man can stop work to be married."

The swarthy host was dazed by this dispatch. "But one moment, Padre. There are all the children to baptize; why not begin with them, if I cannot persuade you to wash the dust from your sainted brow and repose a little."

"Take me to a place where I can wash and change my clothes, and I will be ready before you can get them here. No, I tell you, Lujon, the marriages first, the baptisms afterward; that order is but Christian. I will baptize the children tomorrow morning, and their parents will at least have been married over night."

Father Joseph was conducted to his chamber, and the older boys were sent running off across the fields to fetch the men. Lujon and his two daughters began constructing an altar at one end of the sala. Two old women came to scrub the floor, and another brought chairs and stools.

"My God, but he is ugly, the Padre!" whispered one of these to the others. "He must be very holy. And did you see the great wart he has on his chin? My grandmother could take that away for him if she were alive, poor soul! Somebody ought to tell him about the holy mud at Chimayo. That mud might dry it up. But there is nobody left now who can take warts away."

"No, the times are not so good any more," the other agreed. "And I doubt if all this marrying will make them any better. Of what use is it to marry people after they have lived together and had children? and the man is maybe thinking about another woman, like Pablo. I saw him coming out of the brush with that oldest girl of Trinidad's, only Sunday night."

The reappearance of the priest upon the scene cut short further scandal. He knelt down before the improvised altar and began his private devotions. The women tiptoed away. Señor Lujon himself went out toward the servants' quarters to hurry the candidates for the marriage sacrament. The women were giggling and snatching up their best shawls. Some of the men had even washed their hands. The household crowded into the sala, and Father Vaillant married couples with great dispatch.

"To-morrow morning, the baptisms," he announced. "And the mothers see to it that the children are clean, and that there are sponsors for all."

After he had resumed his travelling-clothes, Father Joseph asked his host at what hour he dined, remarking that he had been fasting since an early breakfast.

"We eat when it is ready— a little after sunset, usually. I have had a young lamb killed for your Reverence."

Father Joseph kindled with interest. "Ah, and how will it be cooked?"

Señ or Lujon shrugged. "Cooked? Why, they put it in a pot with chili, and some onions, I suppose."

"Ah, that is the point. I have had too much stewed mutton. Will you permit me to go into the kitchen and cook my portion in my own way?"

Lujon waved his hand. "My house is yours, Padre. Into the kitchen I never go—too many women. But there it is, and the woman in charge is named Rosa."

When the Father entered the kitchen he found a crowd of women discussing the marriages. They quickly dispersed, leaving old Rosa by her fire-place, where hung a kettle from which issued the savour of cooking mutton fat, all too familiar to Father Joseph. He found a half sheep hanging outside the door, covered with a bloody sack, and asked Rosa to heat the oven for him, announcing that he meant to roast the hind leg.

"But Padre, I baked before the marriages. The oven is almost cold. It will take an hour to heat it, and it is only two hours till supper."

"Very well. I can cook my roast in an hour."

"Cook a roast in an hour!" cried the old woman. "Mother of God, Padre, the blood will not be dried in it!"

"Not if I can help it!" said Father Joseph fiercely. "Now hurry with the fire, my good woman."

When the Padre carved his roast at the supper-table, the serving-girls stood behind his chair and looked with horror at the delicate stream of pink juice that followed the knife. Manuel Lujon took a slice for politeness, but he did not eat it. Father Vaillant had his gigot to himself.