Lucy Gayheart

The Willa Cather Scholarly Edition

Willa Cather

Susan J. Rosowski, 1984-2004

John J. Murphy

Ann Romines

Kari A. Ronning

David Stouck

Paul A. Olson

Robin Schulze

Martha Nell Smith

James L. West III

DAVID PORTER

KARI A. RONNING

University of Nebraska PressLincoln, 1997

CONTENTS

Preface

The objective of the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition is to provide to readers—present and future—various kinds of information relevant to Willa Cather’s writing, obtained and presented according to the highest scholarly standards: a critical text faithful to her intention as she prepared it for the first edition, a historical essay providing relevant biographical and historical facts, explanatory notes identifying allusions and references, a textual commentary tracing the work through its lifetime and describing Cather’s involvement with it, and a record of changes in the text’s various editions. This edition is distinctive in the comprehensiveness of its apparatus, especially in its inclusion of extensive explanatory information that illuminates the fiction of a writer who drew so extensively upon actual experience, as well as the full textual information we have come to expect in a modern critical edition. It thus connects activities that are too often separate—literary scholarship and textual edition.

Editing Cather’s writing means recognizing that Cather was as fiercely protective of her novels as she was of her private life. She suppressed much of her early writing and dismissed serial publication of later work, discarded manuscripts and proofs, destroyed letters, and included in her will a stipulation against publication of her private papers. Yet the record remains surprisingly full. Manuscripts, typescripts, and proofs of some texts survive with corrections and revisions in Cather’s hand; serial publications provide final “draft” versions of texts; correspondence with her editors and publishers helps clarify her intention for a work, and publishers’ records detail each book’s public life; correspondence with friends and acquaintances provides an intimate view of her writing; published interviews with and speeches by Cather provide a running public commentary on her career; and through their memoirs, recollections, and letters, Cather’s contemporaries provide their own commentary on circumstances surrounding her writing.

In assembling pieces of the editorial puzzle, we have been guided by principles and procedures articulated by the Committee on Scholarly Editions of the Modern Language Association. Assembling and comparing texts demonstrated the basic tenet of the textual editor—that only painstaking collations reveal what is actually there. Scholars had assumed, for example, that with the exception of a single correction in spelling, O Pioneers! passed unchanged from the 1913 first edition to the 1937 Autograph Edition. Collations revealed nearly a hundred word changes, thus providing information not only necessary to establish a critical text and to interpret how Cather composed but also basic to interpreting how her ideas about art changed as she matured.

Cather’s revisions and corrections on typescripts and page proofs demonstrate that she brought to her own writing her extensive experience as an editor. Word changes demonstrate her practices in revising; other changes demonstrate that she gave extraordinarily close scrutiny to such matters as capitalization, punctuation, paragraphing, hyphenation, and spacing. Knowledgeable about production, Cather had intentions for her books that extended to their design and manufacture. For example, she specified typography, illustrations, page format, paper stock, ink color, covers, wrappers, and advertising copy.

To an exceptional degree, then, Cather gave to her work the close textual attention that modern editing practices respect, while in other ways she challenged her editors to expand the definition of “corruption” and “authoritative” beyond the text, to include the book’s whole format and material existence. Believing that a book’s physical form influenced its relationship with a reader, she selected type, paper, and format that invited the reader response she sought. The heavy texture and cream color of paper used for O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, for example, created a sense of warmth and invited a childlike play of imagination, as did these books’ large, dark type and wide margins. By the same principle, she expressly rejected the anthology format of assembling texts of numerous novels within the covers of one volume, with tight margins, thin paper, and condensed print.

Given Cather’s explicitly stated intentions for her works, printing and publishing decisions that disregard her wishes represent their own form of corruption, and an authoritative edition of Cather must go beyond the sequence of words and punctuation to include other matters: page format, paper stock, typeface, and other features of design. The volumes in the Cather Edition respect those intentions insofar as possible within a series format that includes a comprehensive scholarly apparatus. For example, the Cather Edition has adopted the format of six by nine inches, which Cather approved in Bruce Rogers’s elegant work on the 1937 Houghton Mifflin Autograph Edition, to accommodate the various elements of design. While lacking something of the intimacy of the original page, this size permits the use of large, generously leaded type and ample margins—points of style upon which the author was so insistent. In the choice of paper, we have deferred to Cather’s declared preference for a warm, cream antique stock.

Today’s technology makes it difficult to emulate the qualities of hot-metal typesetting and letterpress printings. In comparison, modern phototypesetting printed by offset lithography tends to look anemic and lacks the tactile quality of type impressed into the page. The version of the Linotype Caslon typeface employed in the original edition of Lucy Gayheart, were it available for phototypesetting, would hardly survive the transition. Instead, we have chosen Linotype Janson Text, a modern rendering of the type used by Rogers. The subtle adjustments of stroke weight in this reworking do much to retain the integrity of earlier metal versions. Therefore, without trying to replicate the design of single works, we seek to represent Cather’s general preferences in a design that encompasses many volumes.

In each volume in the Cather Edition, the author’s specific intentions for design and printing are set forth in textual commentaries. These essays also describe the history of the texts, identify those that are authoritative, explain the selection of copy-texts or basic texts, justify emendation of the copy-text, and describe patterns of variants. The textual apparatus in each volume—lists of variants, emendations, explanations of emendations, and end-of-line hyphenations—completes the textual story.

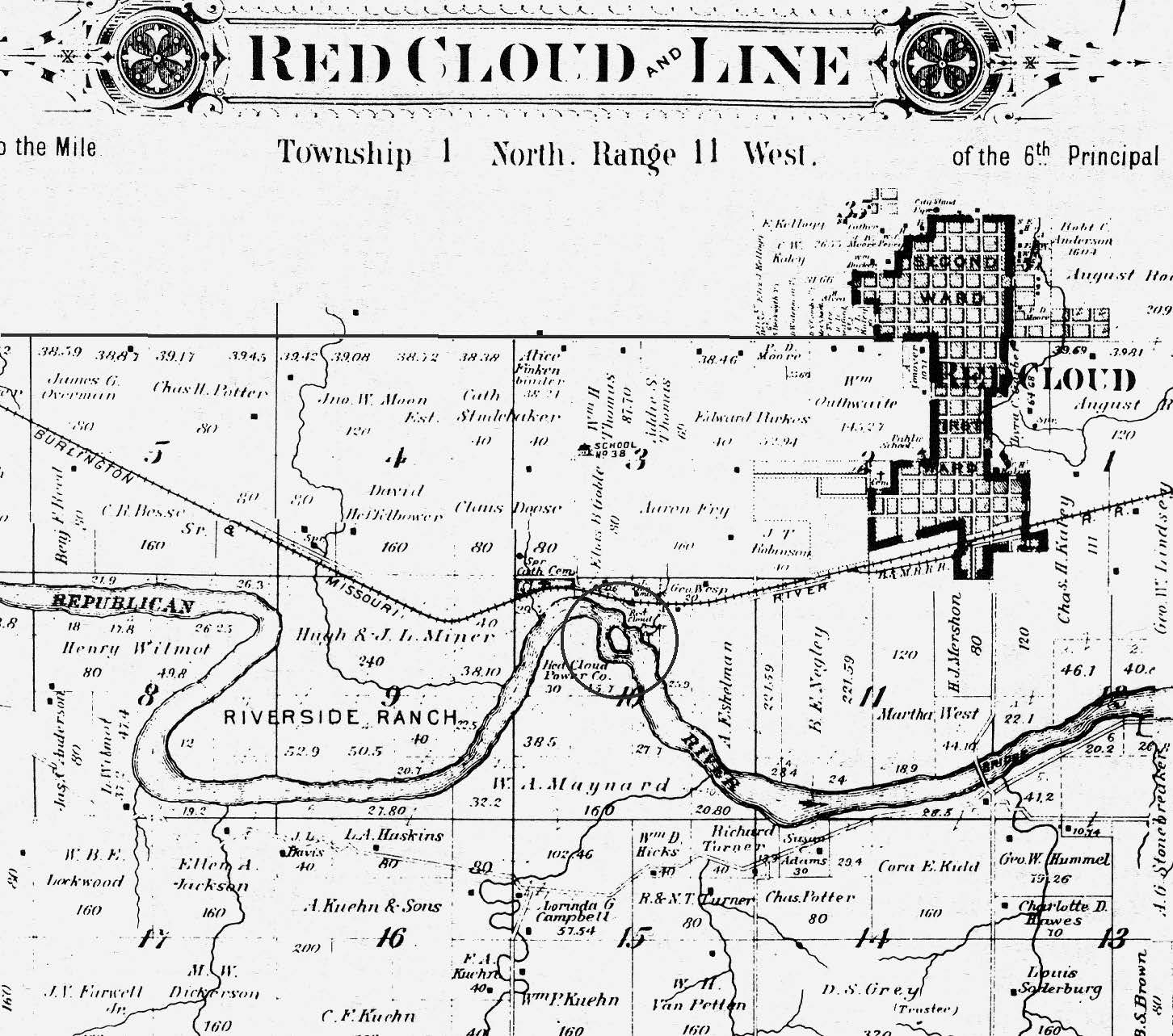

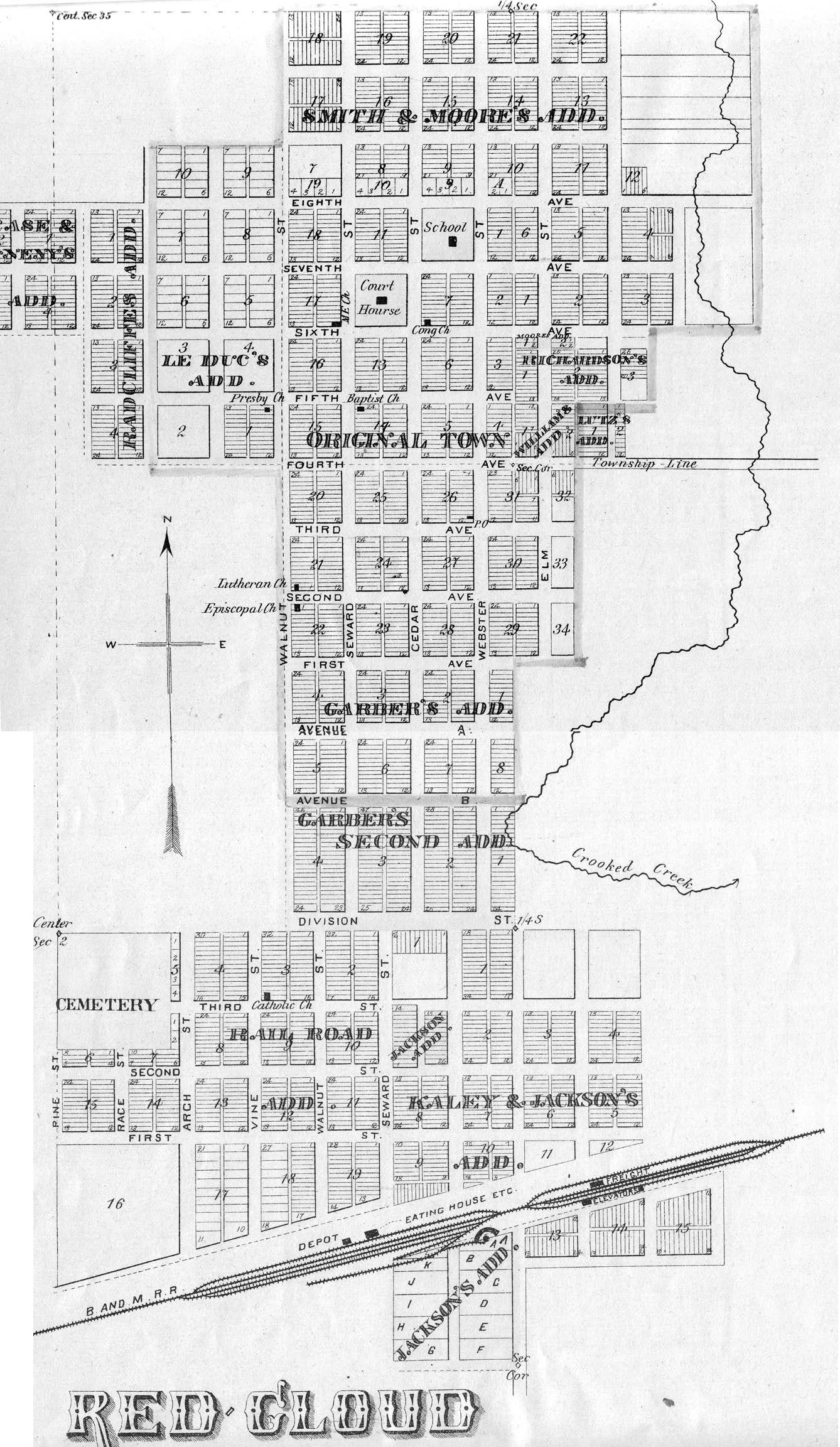

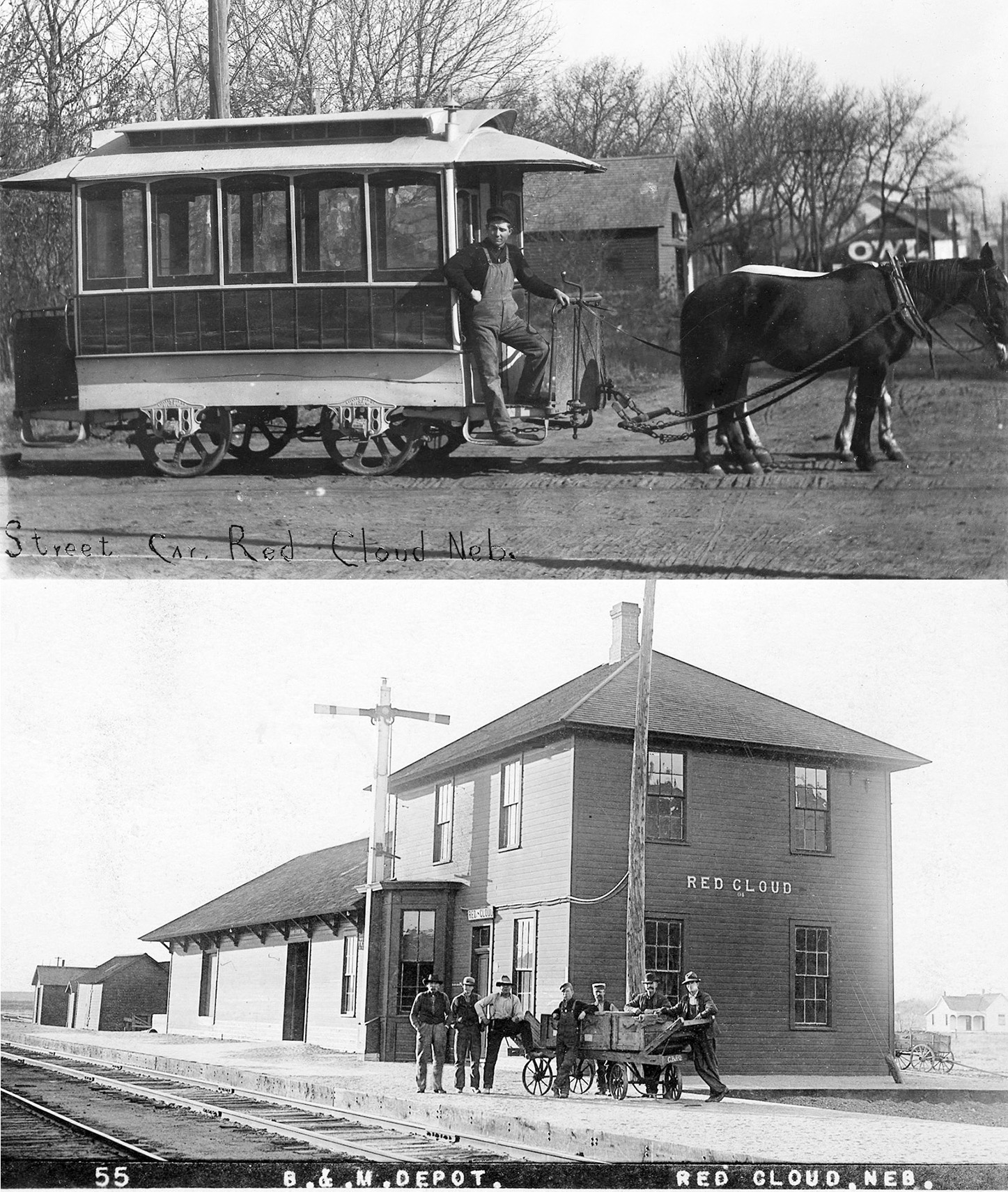

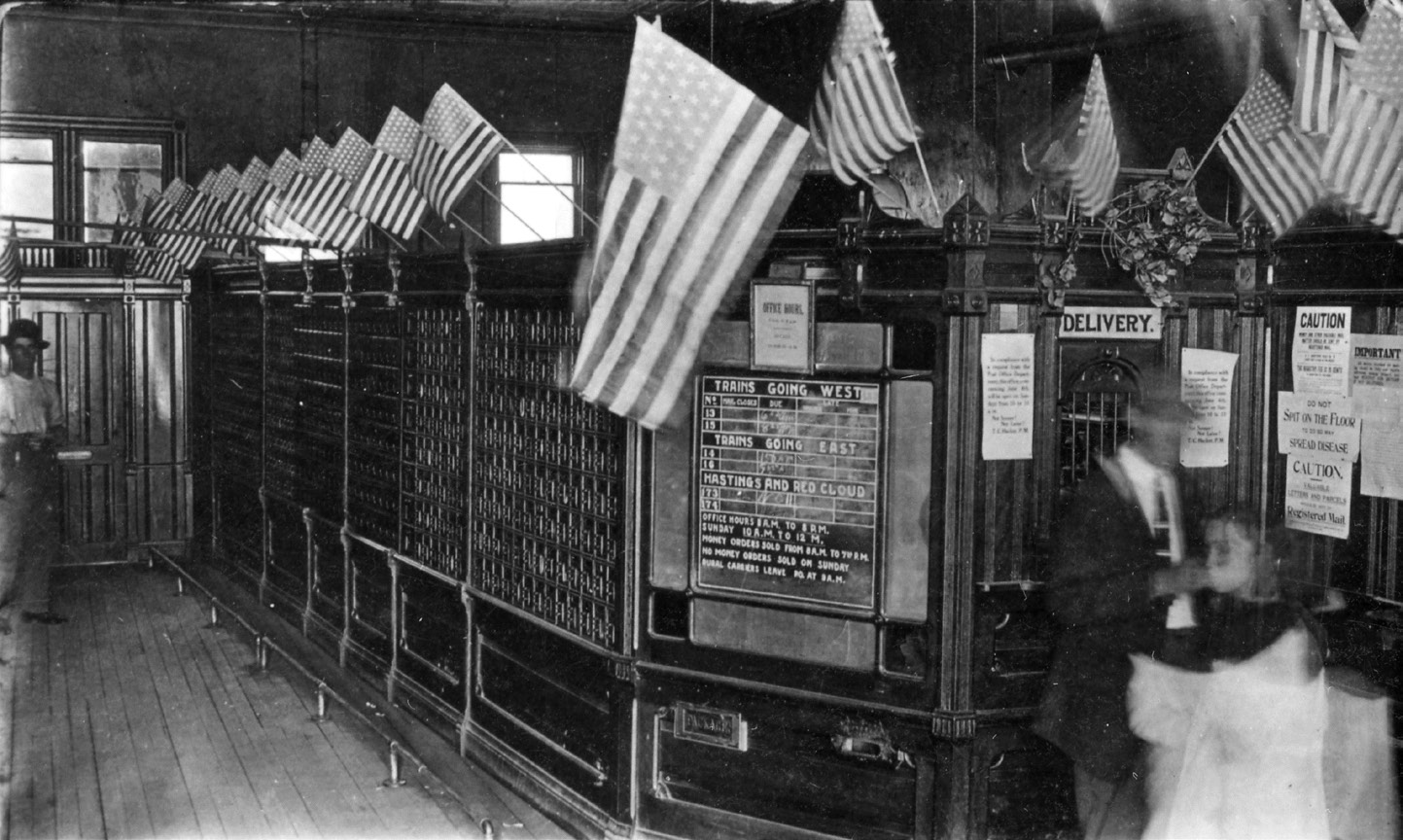

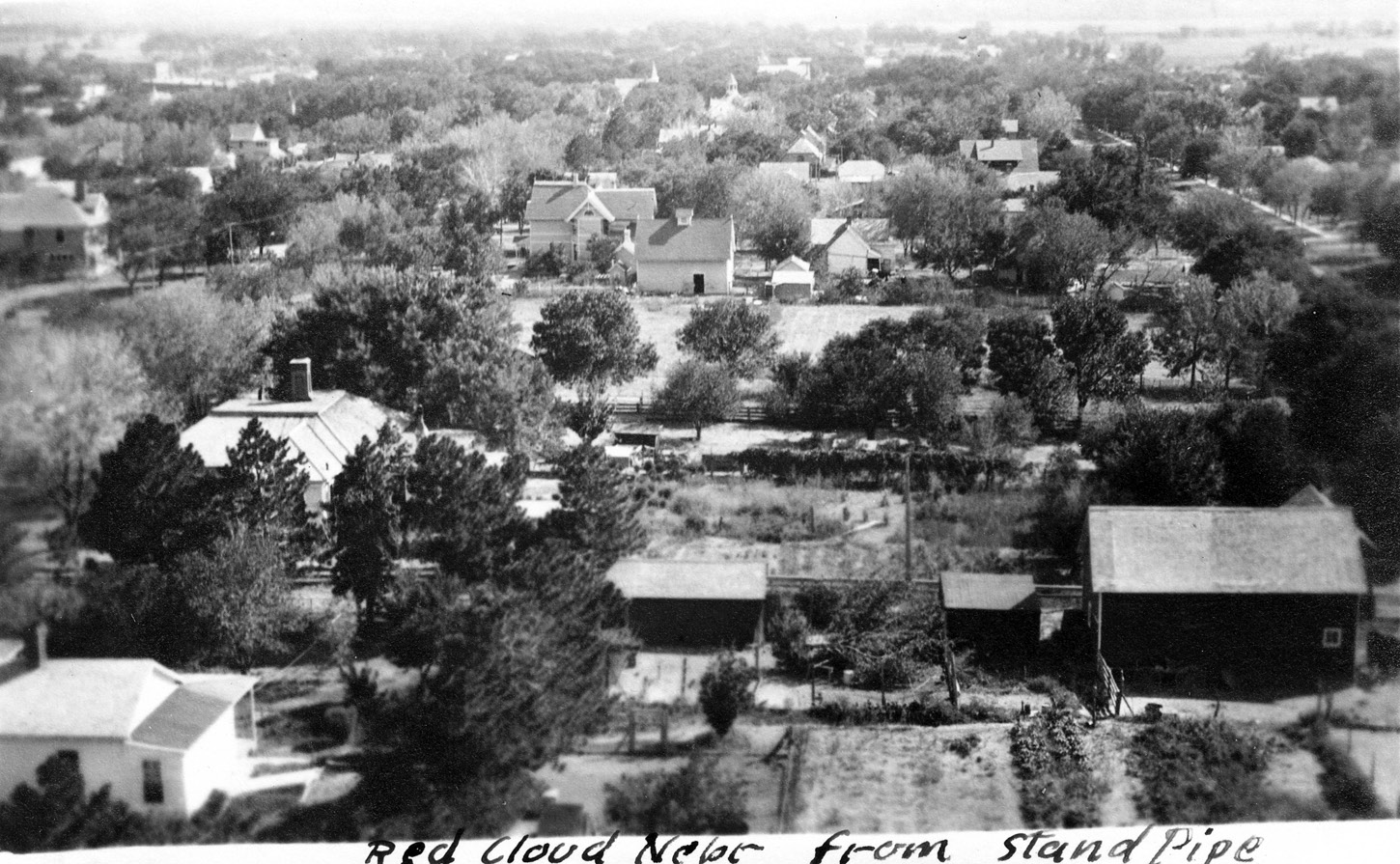

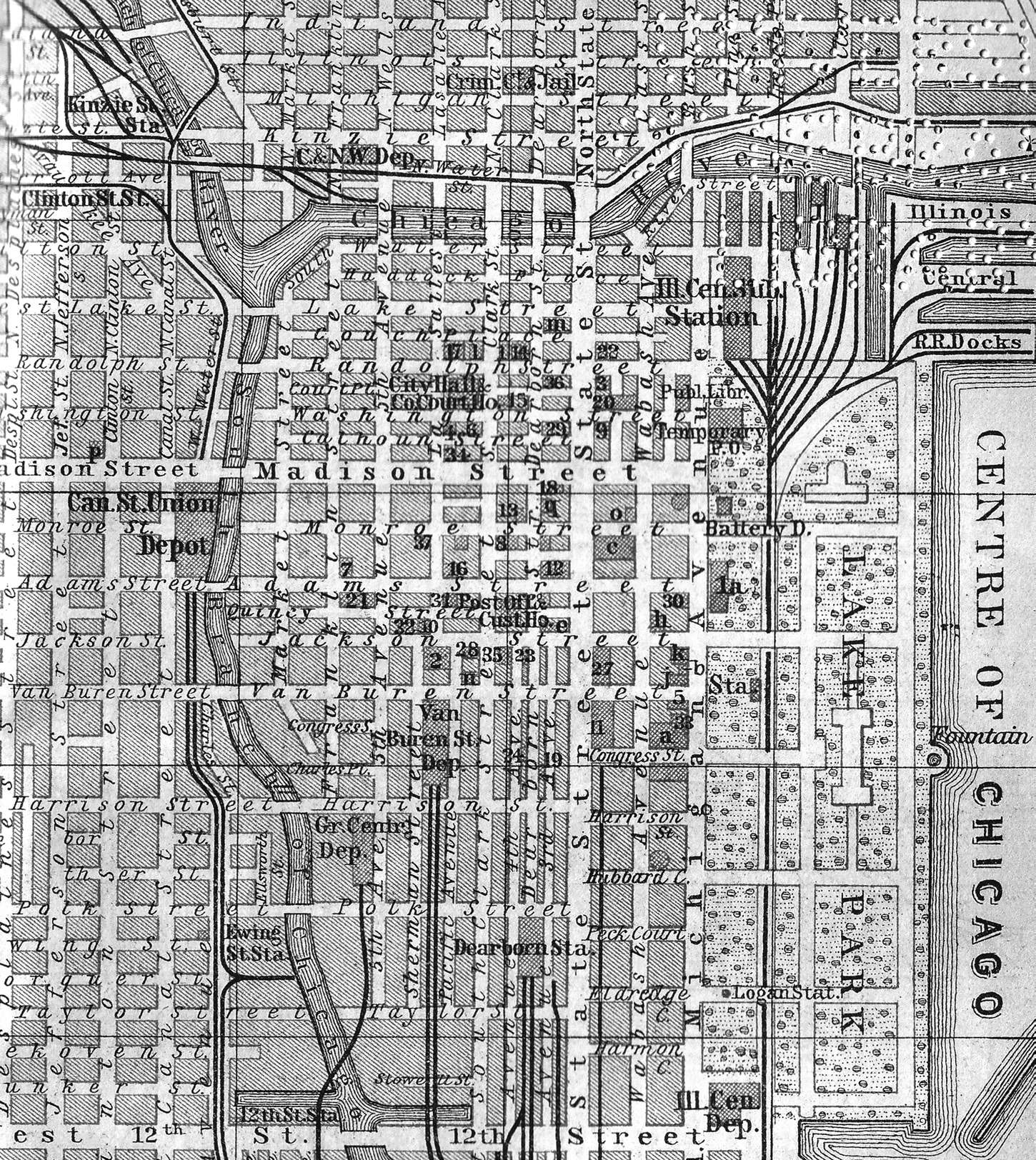

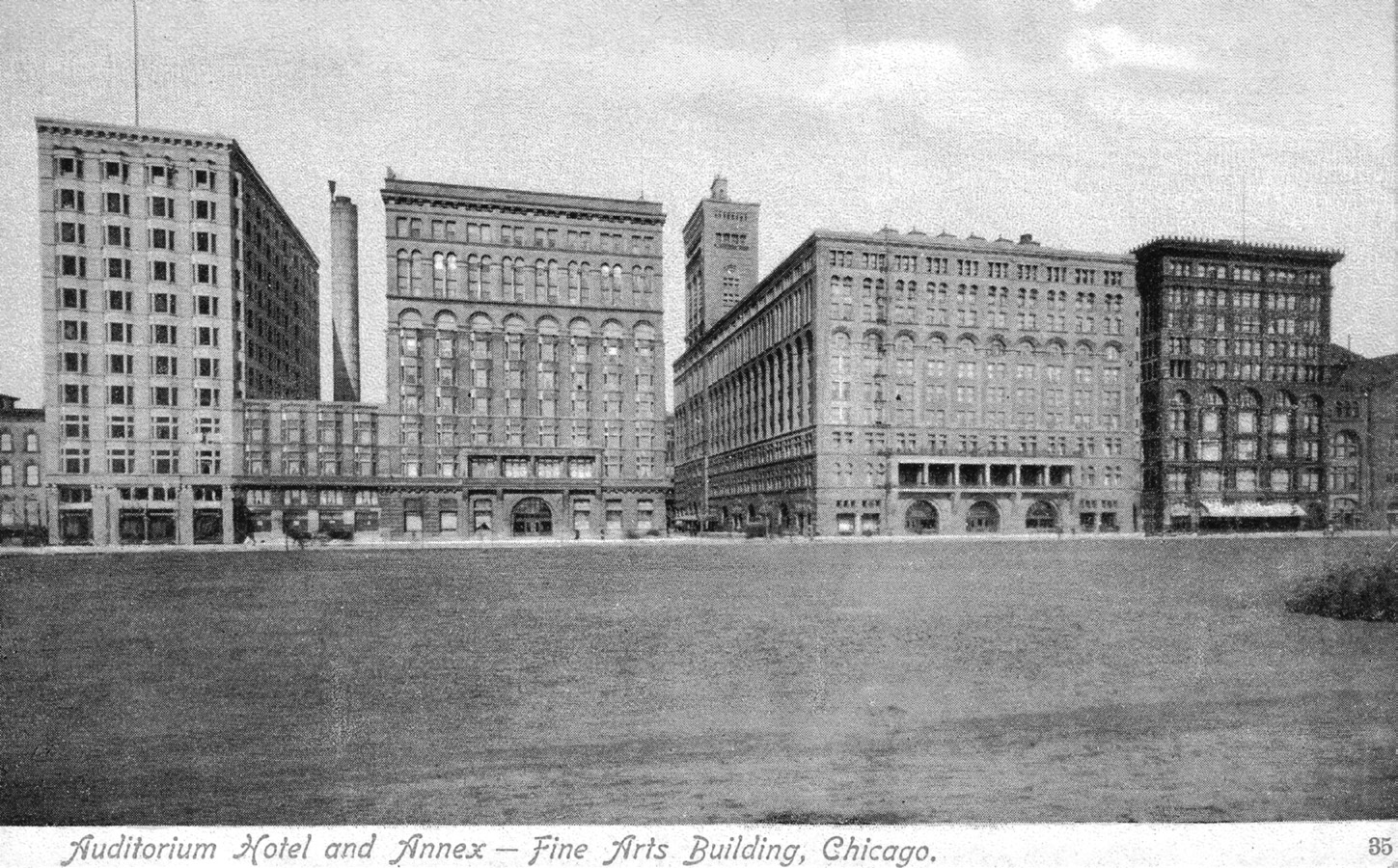

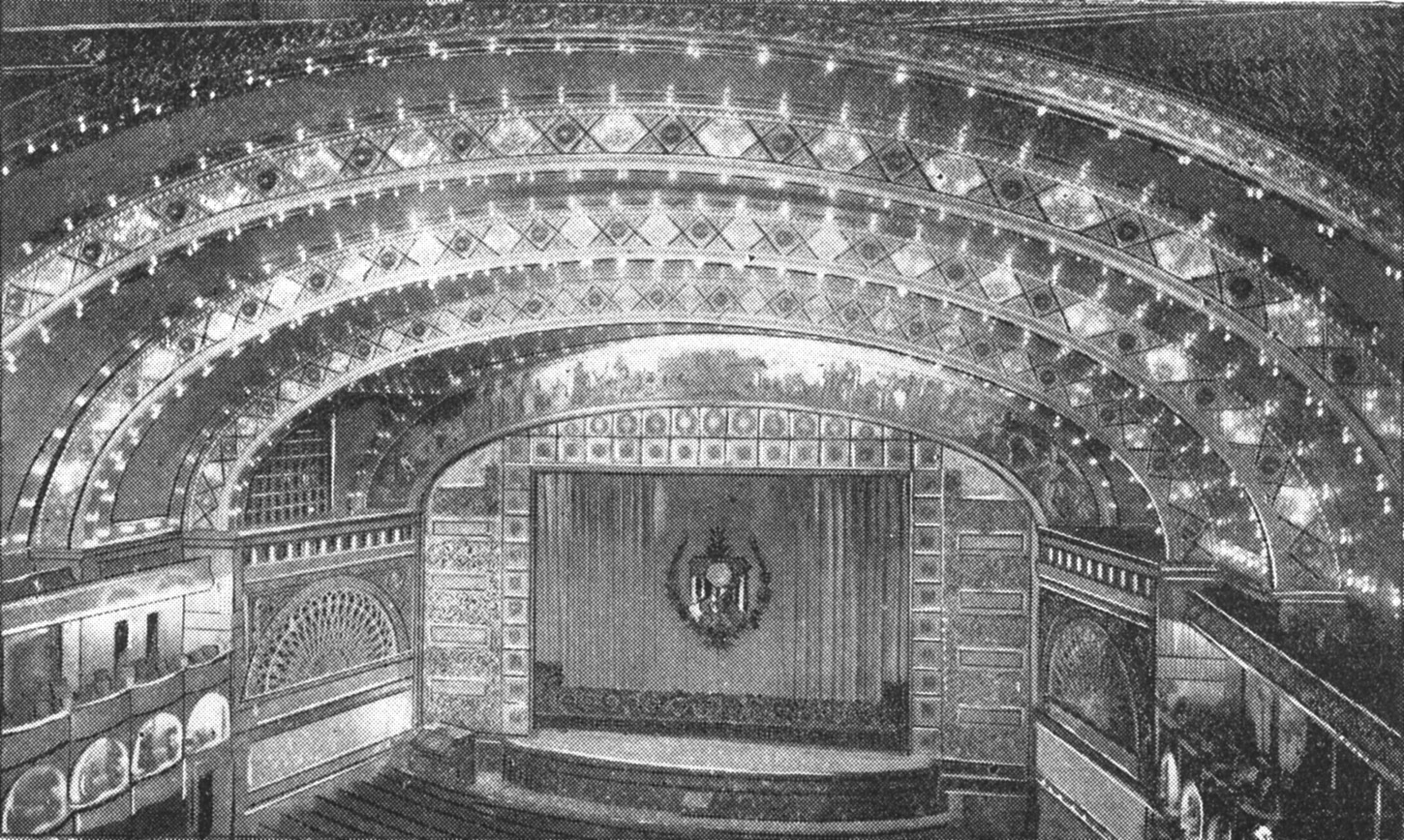

Historical essays provide essential information about the genesis, form, and transmission of each book, as well as supply its biographical, historical and intellectual contexts. Illustrations supplement these essays with photographs, maps, and facsimiles of manuscript, typescript, or typeset pages. Finally, because Cather in her writing draws so extensively upon personal experience and historical detail, explanatory notes are an especially important part of the Cather Edition. By providing a comprehensive identification of her references to flora and fauna, to regional customs and manners, to the classics and the Bible, to popular writing, music, and other arts—as well as relevant cartography and census material—these notes provide a starting place for scholarship and criticism on subjects long slighted or ignored.

Within the overall standard format, differences occur that are informative in their own right. The straightforward textual history of O Pioneers! and My Ántonia contrasts with the more complicated textual challenges of A Lost Lady and Death Comes for the Archbishop; the allusive personal history of the Nebraska novels, so densely woven that My Ántonia seems drawn not merely upon Anna Pavelka but upon all of Webster County, contrast with the more public allusion of novels set elsewhere. The Cather Edition reflects the individuality of each work while providing a standard of reference for critical study.

Susan J. Rosowski

General Editor, 1984–2004

Guy J. Reynolds

General Editor, 2004–

Lucy Gayheart

Willa Cather

BOOK I

I

In Haverford on the Platte the townspeople still talk of Lucy Gayheart. They do not talk of her a great deal, to be sure; life goes on and we live in the present. But when they do mention her name it is with a gentle glow in the face or the voice, a confidential glance which says: “Yes, you, too, remember?” They still see her as a slight figure always in motion; dancing or skating, or walking swiftly with intense direction, like a bird flying home.

When there is a heavy snowfall, the older people look out of their windows and remember how Lucy used to come darting through just such storms, her muff against her cheek, not shrinking, but giving her body to the wind as if she were catching step with it. And in the heat of summer she came just as swiftly down the long shaded sidewalks and across the open squares blistering in the sun. In the breathless glare of August noons, when the horses hung their heads and the workmen “took it slow,” she never took it slow. Cold, she used to say, made her feel more alive; heat must have had the same effect.

The Gayhearts lived at the west edge of Haverford, half a mile from Main Street. People said “out to the Gayhearts’” and thought it rather a long walk in summer. But Lucy covered the distance a dozen times a day, covered it quickly with that walk so peculiarly her own, like an expression of irrepressible light-heartedness. When the old women at work in their gardens caught sight of her in the distance, a mere white figure under the flickering shade of the early summer trees, they always knew her by the way she moved. On she came, past hedges and lilac bushes and woolly-green grape arbours and rows of jonquils, and one knew she was delighted with everything; with her summer clothes and the air and the sun and the blossoming world. There was something in her nature that was like her movements, something direct and unhesitating and joyous, and in her golden-brown eyes. They were not gentle brown eyes, but flashed with gold sparks like that Colorado stone we call the tiger-eye. Her skin was rather dark, and the colour in her lips and cheeks was like the red of dark peonies—deep, velvety. Her mouth was so warm and impulsive that every shadow of feeling made a change in it.

Photographs of Lucy mean nothing to her old friends. It was her gaiety and grace they loved. Life seemed to lie very near the surface in her. She had that singular brightness of young beauty: flower gardens have it for the first few hours after sunrise.

We missed Lucy in Haverford when she went away to Chicago to study music. She was eighteen years old then; talented, but too careless and light-hearted to take herself very seriously. She never dreamed of a “career.” She thought of music as a natural form of pleasure, and as a means of earning money to help her father when she came home. Her father, Jacob Gayheart, led the town band and gave lessons on the clarinet, flute, and violin, at the back of his watch-repairing shop. Lucy had given piano lessons to beginners ever since she was in the tenth grade. Children liked her, because she never treated them like children; they tried to please her, especially the little boys.

Though Jacob Gayheart was a good watchmaker, he wasn’t a good manager. Born of Bavarian parents in the German colony at Belleville, Illinois, he had learned his trade under his father. He came to Haverford young and married an American wife, who brought him a half-section of good farm land. After her death he borrowed money on this farm to buy another, and now they were both mortgaged. That troubled his older daughter, Pauline, but it did not trouble Mr. Gayheart. He took more pains to make the band boys practise than he did to keep up his interest payments. He was a town character, of course, and people joked about him, though they were proud of their band. Mr. Gayheart looked like an old daguerreotype of a minor German poet; he wore a moustache and goatee and had a fine sweep of dark hair above his forehead, just a little grey at the sides. His intelligent, lazy hazel eyes seemed to say: “But it’s a very pleasant world, why bother?”

He managed to enjoy every day from start to finish. He got up early in the morning and worked for an hour in his flower garden. Then he took his bath and dressed for the day, selecting his shirt and necktie as carefully as if he were going to pay a visit. After breakfast he lit a good cigar and walked into town, never missing the flavour of his tobacco for a moment. Usually he put a flower in his coat before he left home. No one ever got more satisfaction out of good health and simple pleasures and a blue-and-gold band uniform than Jacob Gayheart. He was probably the happiest man in Haverford.

2

It was the end of the Christmas holidays, the Christmas of 1901, Lucy’s third winter in Chicago. She was spending her vacation at home. There had been good skating all through Christmas week, and she had made the most of it. Even on her last afternoon, when she should have been packing, she was out with a party of Haverford boys and girls, skating on the long stretch of ice north of Duck Island. This island, nearly half a mile in length, split the river in two,—or, rather, it split a shallow arm off the river. The Platte River proper was on the south side of this island and it seldom froze over; but the shallow stream between the island and the north shore froze deep and made smooth ice. This was before the days of irrigation from the Platte; it was then a formidable river in flood time. During the spring freshets it sometimes cut out a new channel in the soft farm land along its banks and changed its bed altogether.

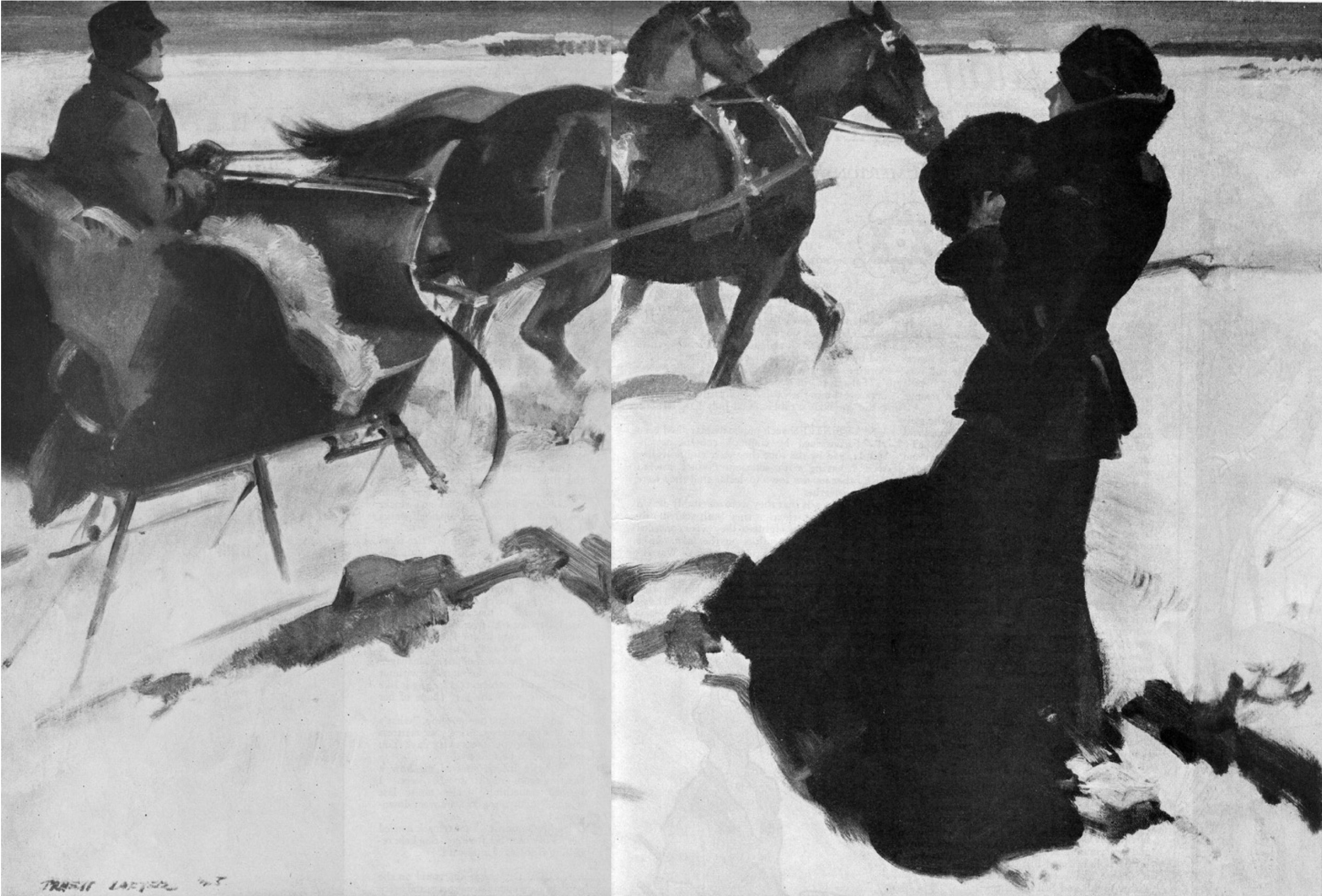

At about four o’clock on this December afternoon a light sleigh with bells and buffalo robes and a good horse came rapidly along the road from town and turned at Benson’s corner into the skating-place. A tall young man sprang out, tied his horse to the hitch-bar, where a row of sleighs already stood, and hurried to the shore with his skating-shoes in his hand. As he put them on, he scanned the company moving over the ice. It was not hard to pick out the figure he was looking for. Six of the strongest skaters had left the others behind and were going against the wind, toward the end of the island. Two were in advance of the rest, Jim Hardwick and Lucy Gayheart. He knew her by her brown squirrel jacket and fur cap, and by her easy stroke. The two ends of a long crimson scarf were floating on the wind behind her, like two slender crimson wings.

Harry Gordon struck out across the ice to overtake her. He, too, was a fine skater; a big fellow, the heavy-weight boxer type, and as light on his feet as a boxer. Nevertheless he was a trifle winded when he passed the group of four and shot alongside Jim Hardwick.

“Jim,” he called, “will you give me a turn with Lucy before the sun goes down?”

“Sure, Harry. I was only keeping her out of mischief for you.” The lad fell back. Haverford boys gave way to Harry Gordon good-naturedly. He was the rich young man of the town, and he was not arrogant or overbearing. He was known as a good fellow; rather hard in business, but liberal with the ball team and the band; public-spirited, people said.

“Why, Harry, you said you weren’t coming!” Lucy exclaimed as she took his arm.

“Didn’t think I could. I did, though. Drove Flicker into a lather getting out here after the directors’ meeting. This is the best part of the afternoon, anyway. Come along.” They crossed hands and went straight ahead in two-step time.

The sun was dropping low in the south, and all the flat snow-covered country, as far as the eye could see, was beginning to glow with a rose-coloured light, which presently would deepen to orange and flame. The black tangle of willows on the island made a thicket like a thorn hedge, and the knotty, twisted, slow-growing scrub-oaks with flat tops took on a bronze glimmer in that intense oblique light which seemed to be setting them on fire.

As the sun declined, the wind grew sharper. They had left the skating party far behind. “Shan’t we turn?” Lucy gasped presently.

“Not yet. I want to get into that sheltered fork of the island. I have some Scotch whisky in my pocket; that will warm you up.”

“How nice! I’m getting a little tired. I’ve been out a long while.”

The end of the island forked like a fish’s tail. When they had rounded one of these points, Harry swung her in to the shore. They sat down on a bleached cottonwood log, where the black willow thicket behind them made a screen. The interlacing twigs threw off red light like incandescent wires, and the snow underneath was rose-colour. Harry poured Lucy some whisky in the metal cup that screwed over the stopper; he himself drank from the flask. The round red sun was falling like a heavy weight; it touched the horizon line and sent quivering fans of red and gold over the wide country. For a moment Lucy and Harry Gordon were sitting in a stream of blinding light; it burned on their skates and on the flask and the metal cup. Their faces became so brilliant that they looked at each other and laughed. In an instant the light was gone; the frozen stream and the snow-masked prairie land became violet, under the blue-green sky. Wherever one looked there was nothing but flat country and low hills, all violet and grey. Lucy gave a long sigh.

Gordon lifted her from the log and they started back, with the wind behind them. They found the river empty, a lonely stretch of blue-grey ice; all the skaters had gone. Harry knew by her stroke that Lucy was tired. She had been out a long while before he came, and she had made a special effort to skate with him. He was sorry and pleased. He guided her in to the shore at some distance from his sleigh, knelt down and took off her skating-shoes, changed his own, and with a sudden movement swung her up in his arms and carried her over the trampled snow to his cutter. As he tucked her under the buffalo robes she thanked him.

“The wind seems to have made me very sleepy, Harry. I’m afraid I won’t do much packing tonight. No matter; there’s tomorrow. And it was a good skate.”

On the drive home Gordon let his sleigh-bells (very musical bells, he had got them to please Lucy) do most of the talking. He knew when to be quiet.

Lucy felt drowsy and dreamy, glad to be warm. The sleigh was such a tiny moving spot on that still white country settling into shadow and silence. Suddenly Lucy started and struggled under the tight blankets. In the darkening sky she had seen the first star come out; it brought her heart into her throat. That point of silver light spoke to her like a signal, released another kind of life and feeling which did not belong here. It overpowered her. With a mere thought she had reached that star and it had answered, recognition had flashed between. Something knew, then, in the unknowing waste: something had always known, forever! That joy of saluting what is far above one was an eternal thing, not merely something that had happened to her ignorance and her foolish heart.

The flash of understanding lasted but a moment. Then everything was confused again. Lucy shut her eyes and leaned on Harry’s shoulder to escape from what she had gone so far to snatch. It was too bright and too sharp. It hurt, and made one feel small and lost.

3

The following night, Sunday evening, all the boys and girls who had been at home for the vacation were going back to school. Most of them would stop at Lincoln; Lucy was the only one going through to Chicago. The train from the west was due to leave Haverford at seven-thirty, and by seven o’clock sleighs and wagons from all directions were driving toward the railway station at the south end of town.

The station platform was soon full of restless young people, glancing up the track, looking at their watches, as if they could not endure their own town a moment longer. Presently a carriage drawn by two horses dashed up to the siding, and the swaying crowd ran to meet it, shouting.

“Here she is, here’s Fairy!”

“Fairy Blair!”

“Hello, Fairy!”

Out jumped a yellow-haired girl, supple and quick as a kitten, with a little green Tyrolese hat pulled tight over her curls. She ripped off her grey fur coat, threw it into the air for the boys to catch, and ran down the platform in her travelling suit—a black velvet jacket and scarlet waistcoat, with a skirt very short indeed for the fashion of that time. Just then a man came out from the station and called that the train would be twenty minutes late. Groans and howls broke from the crowd.

“Oh, hell!”

“What in thunder can we do?”

The green hat shrugged and laughed. “Shut up. Quit swearing. We’ll wake the town.”

She caught two boys by the elbow, and between these stiffly overcoated figures raced out into the silent street, swaying from left to right, pushing the boys as if she were shaking two saplings, and doing an occasional shuffle with her feet. She had a pretty, common little face, and her eyes were so lit-up and reckless that one might have thought she had been drinking. Her fresh little mouth, without being ugly, was really very naughty. She couldn’t push the boys fast enough; suddenly she sprang from between the two rigid figures as if she had been snapped out of a sling-shot and ran up the street with the whole troop at her heels. They were all a little crazy, but as she was the craziest, they followed her. They swerved aside to let the town bus pass.

The bus backed up to the siding. Mr. Gayheart alighted and gave a hand to each of his daughters. Pauline, theelder, got out first. She was short and stout and blonde, like the Prestons, her mother’s people. She was twelve years Lucy’s senior. (Two boys, born between the daughters, died in childhood.) It was Pauline who had brought her sister up; their mother died when Lucy was only six.

Pauline was talking as she got out of the bus, urging her father to hurry and get the trunk checked. “There are always a lot of people in the baggage room, and it takes Bert forever to check a trunk. And be sure you tell him to get it onto this train. When Mrs. Young went to Minneapolis her trunk lay here for twenty-four hours after she started, and she didn’t get it until . . .” But Mr. Gayheart walked calmly away and lost the story of Mrs. Young’s trunk. Lucy remained standing beside her sister, but she did not hear it either. She was thinking of something else.

Pauline took Lucy’s arm determinedly, as if it were the right thing to do, and for a moment she was silent. “Look, there’s Harry Gordon’s sleigh coming up, with the Jenks' boy driving. Do you suppose he is going east tonight?”

“He said he might go to Omaha,” Lucy replied carelessly.

“That’s nice. You will have company,” said Pauline, with the rough-and- ready heartiness she often used to conceal annoyance.

Lucy made no comment, but looked in through a window at the station clock. She had never wanted so much to be moving; to be alone and to feel the train gliding along the smooth rails; to watch the little stations flash by.

Fairy Blair, in her Tyrolese hat, came back from her run quite out of breath and supported by the two boys. As she passed the Gayheart sisters she called:

“Off for the East, Lucy? Wish I were going with you. You musical people get all the fun.” As she and her overcoated props came to a standstill she watched Lucy out of the tail of her eye. They were the two most popular girls in Haverford, and Fairy found Lucy frightfully stuffy and girly-girly. Whenever she met Harry Gordon she tossed her head and flashed at him a look which plainly said: “What in hell do you want with that?”

Mr. Gayheart returned, gave his daughter her trunk check, and stood looking up at the sky. Among other impractical pursuits he had studied astronomy from time to time. When at last the scream of the whistle shivered through the still winter air, Lucy drew a quick breath and started forward. Her father took her arm and pressed it softly; it was not wise to show too much affection for his younger daughter. A long line of swaying lights came out of the flat country to the west, and a moment later the white beam from the headlight streamedalong the steel rails at their feet. The great locomotive, coated with hoar-frost, passed them and stopped, panting heavily.

Pauline snatched her sister and gave her a clumsy kiss. Mr. Gayheart picked up Lucy’s bag and led the way to the right car. He found her seat, arranged her things neatly, then stood looking at her with a discerning, appreciative smile. He liked pretty girls, even in his own family. He put his arm around her, and as he kissed her he murmured in her ear: “She’s a nice girl, my Lucy!” Then he went slowly down the car and got off just as the porter was taking up the step. Pauline was already in a fret, convinced that he would be carried on to the next station.

In Lucy’s car were several boys going back to the University at Lincoln. They at once came to her seat and began talking to her. When Harry Gordon entered and walked down the aisle, they drew back, but he shook his head.

“I’m going out to the diner now. I’ll be back later.”

Lucy shrugged as he passed on. Wasn’t that just like him? Of course he knew that she, and all the other students, would have eaten an early supper at the family board before they started; but he might have asked her and the boys to go out to the dining-car with him and have a dessert or a Welsh rabbit. Another instance of theinstinctive unwastefulness which had made the Gordons rich! Harry could be splendidly extravagant upon occasion, but he made an occasion of it; it was the outcome of careful forethought.

Lucy gave her whole attention to the lads who were so pleased to have it. They were all about her own age, while Harry was eight years older. Fairy Blair was holding a little court at the other end of the car, but distance did not muffle her occasional spasmodic laugh—a curious laugh, like a bleat, which had the effect of an indecent gesture. When this mirth broke out, the boys who were beside Lucy looked annoyed, and drew closer to her, as if protesting their loyalty. She was sorry when Harry Gordon came back and they went away. She received him rather coolly, but he didn’t notice that at all. He began talking at once about the new street-lamps they were to have in Haverford; he and his father had borne half the cost of them.

Harry sat comfortably back in the Pullman seat, but he did not lounge. He sat like a gentleman. He had a good physical presence, whether in action or repose. He was immensely conceited, but not nervously or aggressively so. Instead of being a weakness in him, it amounted to a kind of strength. Such easy self-possession was very reassuring to a mercurial, vacillating person like Lucy.

Tonight, as it happened, Lucy wanted to be alone; but ordinarily she was glad to meet Harry anywhere; to pass him in the post-office or to see him coming down the street. If she stopped for only a word with him, his vitality and unfailing satisfaction with life set her up. No matter what they talked about, it was amusing. She felt absolutely free with him, and she found everything about him genial; his voice, his keen blue eyes, his fresh skin and sandy hair. People said he was hard in business and took advantage of borrowers in a tight place; but neither his person nor his manner gave a hint of such qualities.

While he was chatting confidentially with her about the new street-lamps, Harry noticed that Lucy’s hands were restless and that she moved about in her seat.

“What’s the matter, Lucy? You’re fidgety.”

She pulled herself up and smiled. “Isn’t it silly! Travelling always makes me nervous. But I’m not very used to it, you know.”

“You’re in a hurry to get back. I can tell,” he nodded knowingly. “How about the opera this spring? Will you let me come on for a week and go with me every night?”

“Oh, that will be splendid! But I don’t know about every night. I’m teaching now, you see. I’m much busier than I was last year.”

“We can fix that all right. I’ll make a call on Auerbach. I got on with him first-rate. I told him I had known you ever since you were a youngster.” Harry chuckled and leaned forward a little. “Do you know the first time I ever saw you, Lucy? It was in the old skating-rink. I suppose Haverford was about the last town on earth to have a skating-rink.”

“But that was ages ago. The old rink was pulled down before your bank was built.”

“That’s right. Father and I were staying at the hotel. We had come on to look the town over. One afternoon I was passing the rink and I heard a piano going, so I went in. An old man was playing a waltz, Hearts and Flowers I think they called it. There were a bunch of people on the floor, but I picked you out first shot. You must have been about thirteen, with your hair down your back. You had on a short skirt and a skin-tight red jersey, and you were going like a streak. I thought you had the prettiest eyes in the world—Still think so,” he added, puckering his brows, as if he were making a grave admission.

Lucy laughed. Harry was cautious, even in compliments.

“Oh, thank you, Harry! I had such good times in that old rink. I missed it terribly after it was pulled down. Pauline wouldn’t let me go to dances then. But I don’tremember you very well until you began to pitch for Haverford. Everyone was crazy about your in-curves. Why did you give up baseball?”

“Too lazy, I guess.” He shrugged his smooth shoulders. “I liked playing ball, though. But now about the opera. You’ll keep the first two weeks of April open for me? I can’t tell now just when I’ll be able to run on.”

Young Gordon was watching Lucy as they talked, and thinking that he had about made up his mind. He wasn’t rash, he hadn’t been in a hurry. He didn’t like the idea of marrying the watchmaker’s daughter, when so many brilliant opportunities were open to him. But as he had often told himself before, he would just have to swallow the watchmaker. During the two winters Lucy had been away in Chicago, he had played about with lots of girls in the cities where his father’s business took him. But there was simply nobody like her,—for him, at least.

Tomorrow he would have to deal with a rather delicate situation. Harriet Arkwright, of the St. Joseph Arkwrights, was visiting a friend in Omaha, and she had telephoned him to come on and take her to a dance. He had carried things along pretty far with Miss Arkwright. Her favour was flattering to a small-town man. She was a person of position in St. Joe. Her father was president of the oldest banking house, and she had a considerable fortune of herown, from her mother. If she was twenty-six years old and still unmarried, it was not from lack of suitors. She had been in no hurry to tie herself up. She managed her own property very successfully, travelled a good deal, liked her independence. A woman of the world, Harry considered her; good style, always at her ease, had a kind of authority that money and social position give. But she was plain, confound it! She looked like the men of her family. And she had a hard, matter-of- fact voice, which never kindled with anything; slightly nasal. Whatever she spoke of, she divested of charm. If she thanked him for his gorgeous roses, her tone deflowered the flowers.

Harry liked to play with the idea of how such a marriage would affect his future, but he had never tried to make himself believe that he was in love with Harriet. Strangely enough, the only girl who gave him any deep thrill was this same Lucy, who lived in his own town, was poor as a church mouse, never flattered him, and often laughed at him. When he was with her, life was different; that was all.

And she was growing up, he realized. All through the Christmas vacation he had felt a change in her. She was perhaps a trifle more reserved. At the dance, on New Year’s Eve, he thought she held herself away from him just a little—and from everyone else. She wasn’t cold, she hadnever looked lovelier, never been more playfully affectionate toward her old friends. But she was not there in the old way. All evening her eyes shone with something she did not tell him. The moment she was not talking to someone, that look came back. And in every waltz she seemed to be looking over his shoulder at something—positively enchanting! . . . whereas there was only the same old crowd, dancing in the Masonic Hall, with a “crash” over the Masonic carpet. He would not soon forget that New Year’s Eve. It had brought him up short. Lucy wasn’t an artless, happy little country girl any longer; she was headed toward something. He had better be making up his mind. Even tonight, here on the train, when she seemed to give him her whole attention, she didn’t, really.

The porter came for Gordon’s bags, and said they were pulling into Omaha. Lucy went out to the vestibule with Harry, and they talked in low tones during the stop. He stood holding her hand and looking down at her with that blue-eyed friendliness which seemed so transparent and uncalculating, until the porter called “All aboard!” Harry kissed her on the cheek and stepped down to the station platform. Lucy waved to him through the window while the train was pulling out.

Gordon got into a horse cab and started for his hotel. His chin was lowered in his muffler, and he smiled at thestreet-lights as the cab rattled along. Yes, he told himself, he must use diplomacy with Miss Arkwright for a while longer. Her stock was going down. He meant to commit the supreme extravagance and marry for beauty. He meant to have a wife other men would envy him.

Lucy undressed quickly, got into her berth, and turned off the lights. At last she was alone, lying still in the dark, and could give herself up to the vibration of the train,—a rhythm that had to do with escape, change, chance, with life hurrying forward. That sense of release and surrender went all over her body; she seemed to lie in it as in a warm bath. Tomorrow night at this time she would be coming home from Clement Sebastian’s recital. In a few hours one could cover that incalculable distance; from the winter country and homely neighbours, to the city where the air trembled like a tuning-fork with unimaginable possibilities.

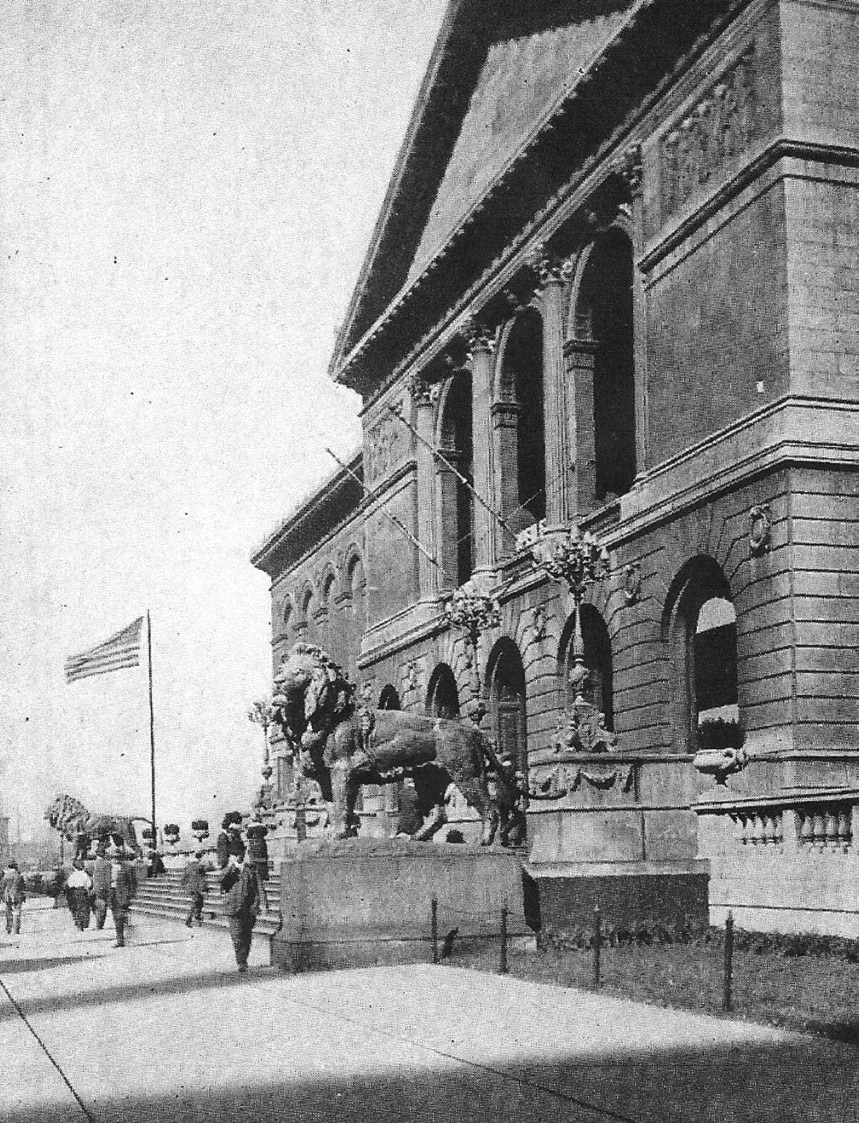

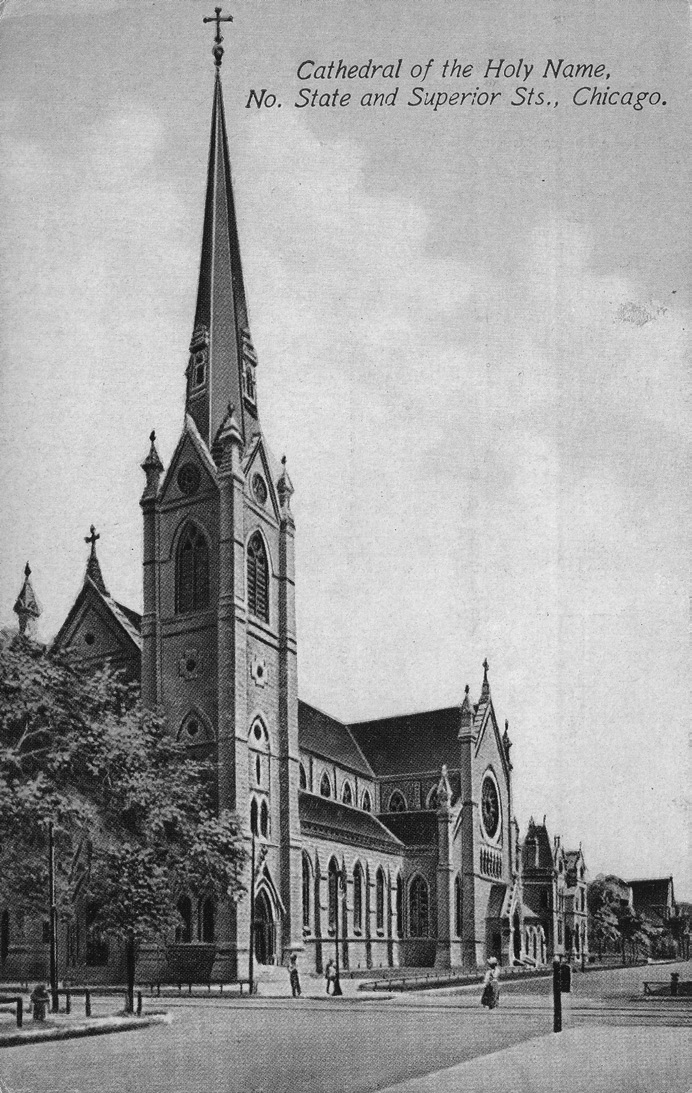

Lucy carried in her mind a very individual map of Chicago: a blur of smoke and wind and noise, with flashes of blue water, and certain clear outlines rising from the confusion; a high building on Michigan Avenue where Sebastian had his studio—the stretch of park where he sometimes walked in the afternoon—the Cathedral door out of which she had seen him come one morning—theconcert hall where she first heard him sing. This city of feeling rose out of the city of fact like a definite composition,—beautiful because the rest was blotted out. She thought of the steps leading down from the Art Museum as perpetually flooded with orange-red sunlight; they had been like that one stormy November afternoon when Sebastian came out of the building at five o’clock and stopped beside one of the bronze lions to turn up the collar of his overcoat, light a cigarette, and look vaguely up and down the avenue before he hailed a cab and drove away.

In the round of her day’s engagements, hurrying about Chicago from one place to another, Lucy often came upon spots which gave her a sudden lift of the heart, made her feel glad before she knew why. Tonight, lying in her berth, she thought she would be happy to be going back, even if Clement Sebastian were no longer there. She would still be going back to “the city,” to the place where so many memories and sensations were piled up, where a window or a doorway or a street-corner with a magical meaning might at any moment flash out of the fog.

4

The next morning Lucy was in Chicago, in her own room, unpacking and putting her things to rights. She lived in a somewhat unusual manner; had a room two flights up over a bakery, in one of the grimy streets off the river.

When she first came to Chicago she had stayed at a students’ boarding-house, but she didn’t like the pervasive informality of the place, nor the Southern gentlewoman of fallen fortunes who conducted it. She told her teacher, Professor Auerbach, that she would never get on unless she could live alone with her piano, where there would be no gay voices in the hall or friendly taps at her door. Auerbach took her out to his house, and they consulted with his wife. Mrs. Auerbach knew exactly what to do. She and Lucy went to see Mrs. Schneff and her bakery.

The Schneff bakery was an old German landmark in that part of the city. On the ground floor was the bake shop, and a homely restaurant specializing in German dishes, conducted by Mrs. Schneff. On the top floor was a glove factory. The three floors between, the Schneffs rented to people who did not want to take long leases;travelling salesmen, clerks, railroad men who must be near the station. The food in the bakery downstairs was good enough, and there were no table companions or table jokes. Everyone had his own little table, attended to his own business, and read his paper. Lucy had taken a room here at once, and for the first time in her life she could come and go like a boy; no one fussing about, no one hovering over her. There were inconveniences, to be sure. The lodgers came and went by an open stairway which led up from the street beside the front door of the restaurant; the winter winds blew up through the halls—burglars might come, too, but so far they never had. There was no parlour in which Lucy could receive callers. When she went anywhere with one of Auerbach’s students, the young man waited for her on the stairway, or met her in the restaurant below.

This morning Lucy was glad as never before to be back with her own things and her own will. After she had unpacked, she arranged and rearranged; nothing was too much trouble. The moment she had shut the door upon the baggage man, she seemed to find herself again. Out there in Haverford she had scarcely been herself at all; she had been trying to feel and behave like someone she no longer was; as children go on playing the old games to please their elders, after they have ceased to be childrenat heart. Coming up from the station, through a pecking fall of sleet, she wondered whether something she had left in this room might have vanished in her absence; might not be there to welcome her. It was here she had come the night after she first heard Clement Sebastian, and here she had brought back all her chance glimpses of him. These four walls held all her thoughts and feelings about him. Her memories did not stand out separately; they were blended and pervasive. They made the room seem larger than it was, quieter and more guarded; gave it a slight austerity.

Since she was going to Sebastian’s recital tonight, Lucy had her dinner early, in the restaurant below. When she came upstairs again, it was not yet time to dress. She put on her dressing-gown, turned out the gas light, and lay down to reflect.

Only three months ago, early in October, Professor Auerbach had told her that his old friend, Clement Sebastian, was in Chicago, and that she must hear him—probably he would not be there long. He was a man one couldn’t afford to miss. But Lucy had little money and many wants; a baritone voice didn’t seem to be one of the most vehement. She missed his first recital without regret, though afterwards the newspaper notices, and the talk she heardamong the students, aroused her curiosity. The following week he gave a benefit recital for the survivors of a mine disaster. Auerbach got a single ticket for her, and she went alone. She had dressed here, in this room, without much enthusiasm, rather reluctant to go out again after a tiring day. She had turned on the steam heat and put out the gas and gone downstairs, anticipating nothing.

Sebastian’s personality had aroused her, even before he began to sing, the moment he came upon the stage. He was not young, was middle-aged, indeed, with a stern face and large, rather tired eyes. He was a very big man; tall, heavy, broad-shouldered. He took up a great deal of space and filled it solidly. His torso, sheathed in black broadcloth and a white waistcoat, was unquestionably oval, but it seemed the right shape for him. She said to herself immediately: “Yes, a great artist should look like that.”

The first number was a Schubert song she had never heard or even seen. His diction was one of the remarkable things about Sebastian’s singing, and she did not miss a word of the German. A Greek sailor, returned from a voyage, stands in the temple of Castor and Pollux, the mariners’ stars, and acknowledges their protection. He has steered his little boat by their mild, protecting light, eure Milde, eure Wachen. In recognition of their aid he hangs his oar as a votive offering in the porch of their temple.

The song was sung as a religious observance in the classical spirit, a rite more than a prayer; a noble salutation to beings so exalted that in the mariner’s invocation there was no humbleness and no entreaty. In your light I stand without fear, O august stars! I salute your eternity. That was the feeling. Lucy had never heard anything sung with such elevation of style. In its calmness and serenity there was a kind of large enlightenment, like daybreak.

After this invocation came five more Schubert songs, all melancholy. They made Lucy feel that there was something profoundly tragic about this man. The dark beauty of the songs seemed to her a quality in the voice itself, as kindness can be in the touch of a hand. It was as simple as that—like light changing on the water. When he began Der Doppelgänger, the last song of the group (Still ist die Nacht, es ruhen die Gassen), it was like moonlight pouring down on the narrow street of an old German town. With every phrase that picture deepened—moonlight, intense and calm, sleeping on old human houses; and somewhere a lonely black cloud in the night sky. So manche Nacht in alter Zeit? The moon was gone, and the silent street.—And Sebastian was gone, though Lucy had not been aware of his exit. The black cloud that had passed over the moon and the song had obliterated him, too. There was nobody left before the grey velvet curtain butthe red-haired accompanist, a lame boy, who dragged one foot as he went across the stage.

Through the rest of the recital her attention was intermittent. Sometimes she listened intently, and the next moment her mind was far away. She was struggling with something she had never felt before. A new conception of art? It came closer than that. A new kind of personality? But it was much more. It was a discovery about life, a revelation of love as a tragic force, not a melting mood, of passion that drowns like black water. As she sat listening to this man the outside world seemed to her dark and terrifying, full of fears and dangers that had never come close to her until now.

A note on the program said there would be no encores. After the last number, when the singer had repeatedly come back to acknowledge applause, the lights above the stage were turned out. But the audience remained seated. A French basso from the New York opera, who happened to be in town, occupied a stage box with a party of friends. He kept calling:

“Clément! Clément!”

At last the baritone came back, his coat on his arm and his hat in his hand. He bowed to his colleague, the bass, then turned aside and spoke through the stage door. The lame boy appeared; they had a word together underthe applause. Sebastian walked to the front of the stage in the half-darkness and began to sing an old setting of Byron’s When We Two Parted; a sad, simple old air which required little from the singer, yet probably no one who heard it that night will ever forget it.

Lucy had come home and up the stairs, into this room, tired and frightened, with a feeling that some protecting barrier was gone—a window had been broken that let in the cold and darkness of the night. Sitting here in her cloak, shivering, she had whispered over and over the words of that last song:

When we two parted,/ In silence and tears,/ Half broken-hearted,/ To sever for years,// Pale grew thy cheek and cold, /Colder thy kiss;/ Surely that hour foretold/ Sorrow to this.

It was as if that song were to have some effect upon her own life. She tried to forget it, but it was unescapable. It was with her, like an evil omen; she could not get it out of her mind. For weeks afterwards it kept singing itself over in her brain. Her forebodings on that first nighthad not been mistaken; Sebastian had already destroyed a great deal for her. Some people’s lives are affected by what happens to their person or their property; but for others fate is what happens to their feelings and their thoughts—that and nothing more.

The following day Lucy had questioned Paul Auerbach about Sebastian, at first timidly, then fiercely. What was his history? What had he been like as a boy? What made him different from other singers?

“Oh, but,” said Professor Auerbach calmly, “Clement is very exceptional; he is a fine artist.” This exasperated her. It was like saying, This is a black horse, or, This is a tall tree. Auerbach promised her that she should meet him some time, but it never seemed to come off.

Then one afternoon, a few days before the Christmas vacation, Auerbach came into the back room where Lucy was just finishing with a pupil and told her he had a surprise for her. Sebastian would be here at the studio at ten o’clock tomorrow morning. His accompanist, James Mockford, was to have an operation on his hip when he got home to England, and for the present his doctor wanted him to spend his mornings in bed. He might be able to keep his concert dates, if he got rid of the routine work. Sebastian was looking for someone to accompany him in his practice hours. He was coming tomorrow totry out several of Auerbach’s pupils, and Lucy would have a chance to play for him.

“He wants someone young and teachable, not somebody who will try to teach him. I think you might please him, Lucy. I spoke for you.”

That night, of course, she slept very little. She had never been nervous when Auerbach asked her to play for his friends; he had told her this was because she was not ambitious,—that it was her greatest fault. But this time it was different. If she didn’t please Sebastian, she would probably never meet him again. If she did please him—But that possibility frightened her more than the other. For an ordinary singer she thought she could do very well; but she could never play for him. She hadn’t it in her. By five o’clock in the morning she had decided not to appear at the studio at all; she would decline the risk.

With her breakfast, courage revived. To this day she could not remember how she ever got to Auerbach’s studio, but she arrived there. As she approached the door, she heard Sebastian singing the “Largo al factotum” from the Barber of Seville. It must be John Patterson at the piano. She slipped in quietly. It was an easier entrance than she had hoped for. When the aria was over, Auerbach introduced her. Sebastian was easy and kindly. He took her hand and looked straight into her eyes.

“Shall we set to work at once, Miss Gayheart, or had you rather wait a bit, while Mr. Schneller and I try our luck?”

“I’d rather try now, if you please,” she said decidedly.

He laughed. “And get it over with? Don’t be nervous. It’s no great matter. We might try this same aria. I seemed not to do it very well.”

Poor young Patterson flushed under his sandy hair; he knew what that meant.

“Have you ever played the piano accompaniment?” Sebastian asked as she sat down.

“I haven’t happened to. But I’ve heard the opera.”

When they finished he began turning over his music. “Now suppose we take something quite different.” He put an aria from Massenet’s Hérodiade, “Vision fugitive,” on the rack before her.

Afterwards he called Mr. Schneller, and Lucy sat in a deep corner of the sofa, remembering the mistakes she had made. Presently she heard Sebastian thanking the two young men and telling Auerbach they were a credit to him.

“Now, my boys, I won’t keep you any longer. We will have another practice morning one of these days. I’m going to detain Miss Gayheart; she was a little nervous and I want her to try again.” He shook hands with Schnellerand Patterson, and they left. Then he took Auerbach’s arm and walked with him toward the sofa where Lucy was sitting. “On the whole, Paul, I think Miss Gayheart would be the best risk. She is a little uncertain, but she has much the best touch.”

Auerbach spoke up for her.

“She’s not usually uncertain. I was surprised when she went wrong in the Massenet. She reads well at sight.”

“I was frightened, Mr. Auerbach,” Lucy said feebly.

The large man in the double-breasted morning coat stood before her and smiled encouragingly. “I know when people are frightened, my dear. I’ve seen it before. The point is, you do not make ugly sounds; that puts me out more than anything. After the holidays you must come to my studio and we’ll try an hour’s practice together. That’s the only way to arrive at anything. Just when do you get back from your vacation?”

On the 3rd of January, she told him.

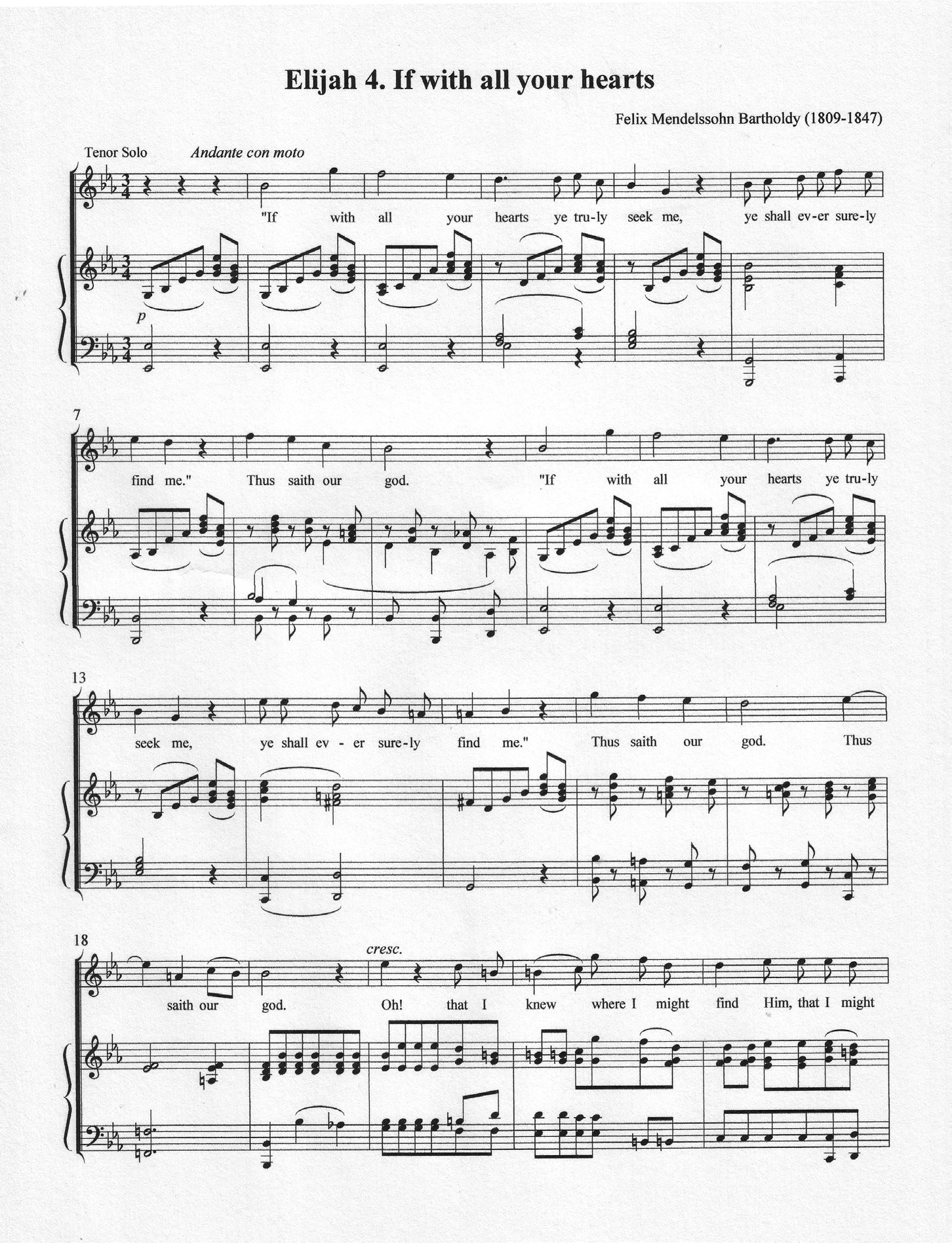

“Very well, shall we say January 4th, at ten o’clock, in my studio on Michigan Avenue?” He took a notebook from his pocket and wrote it down. “You might take the score of Elijah with you and glance over it.” Again he looked at her intently, with real kindness in his eyes. “Good-bye, Miss Gayheart, and a pleasant holiday.”

That was the last time she had seen him.

Tonight she would hear his Schubert program, and tomorrow morning at ten she was to be at his studio.

Lucy sprang up from her bed; it was almost time to start for the concert. She slipped into her only evening dress and put on the velvet cloak she had bought just before she went home for Christmas. It was very pretty, she thought, and becoming (she had quite impoverished herself to have it), but it was not very warm. Tonight there was a bitter wind blowing off the Lake, but she was going to have a cab—anyway, she was not afraid of the cold. She rather liked the excitement of winding a soft, light cloak about her bare arms and shoulders and running out into a glacial cold through which one could hear the hammer-strokes of the workmen who were thawing out switches down on the freight tracks with gasoline torches. The thing to do was to make an overcoat of the cold; to feel one’s self warm and awake at the heart of it, one’s blood coursing unchilled in an air where roses froze instantly.

5

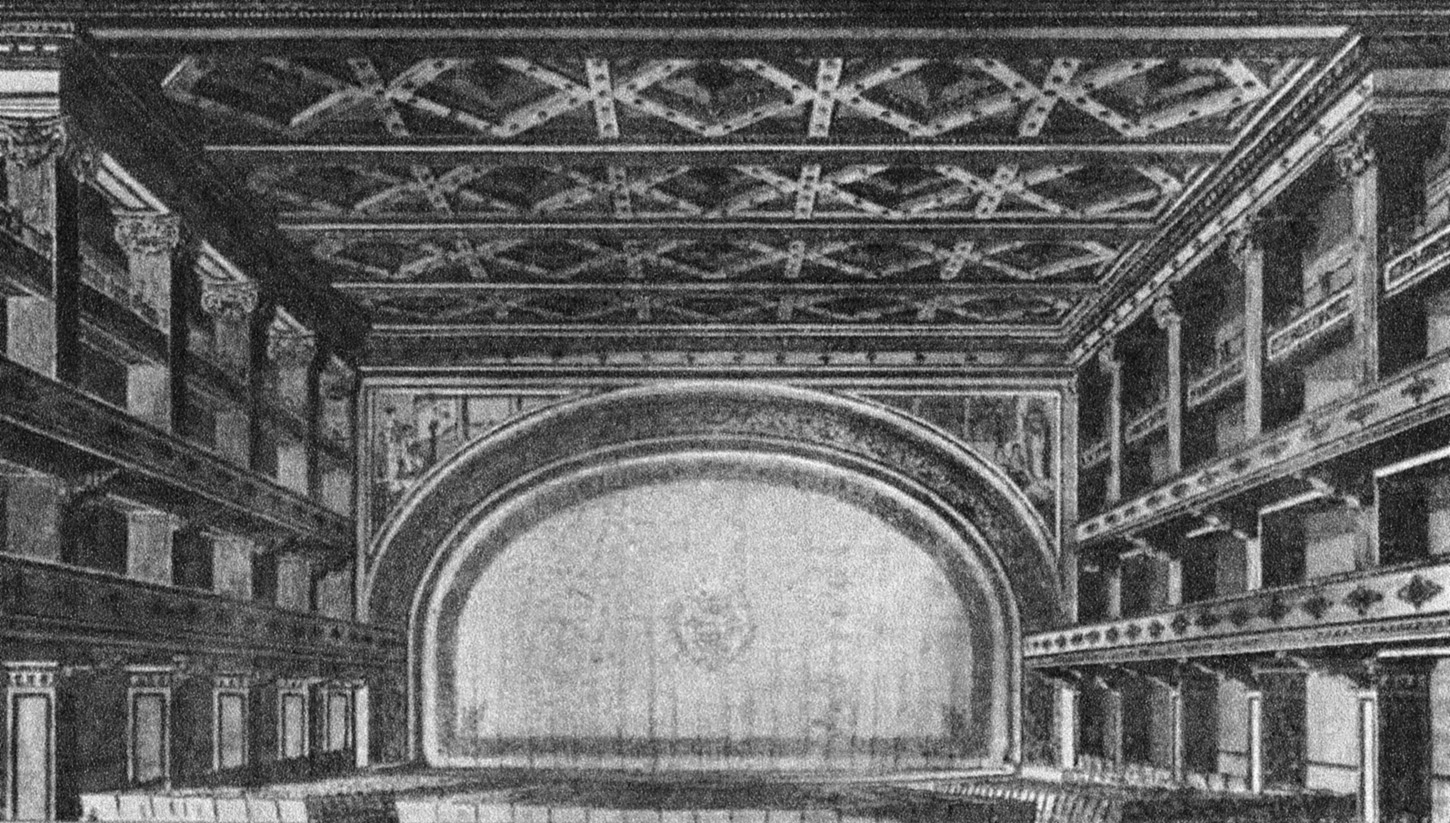

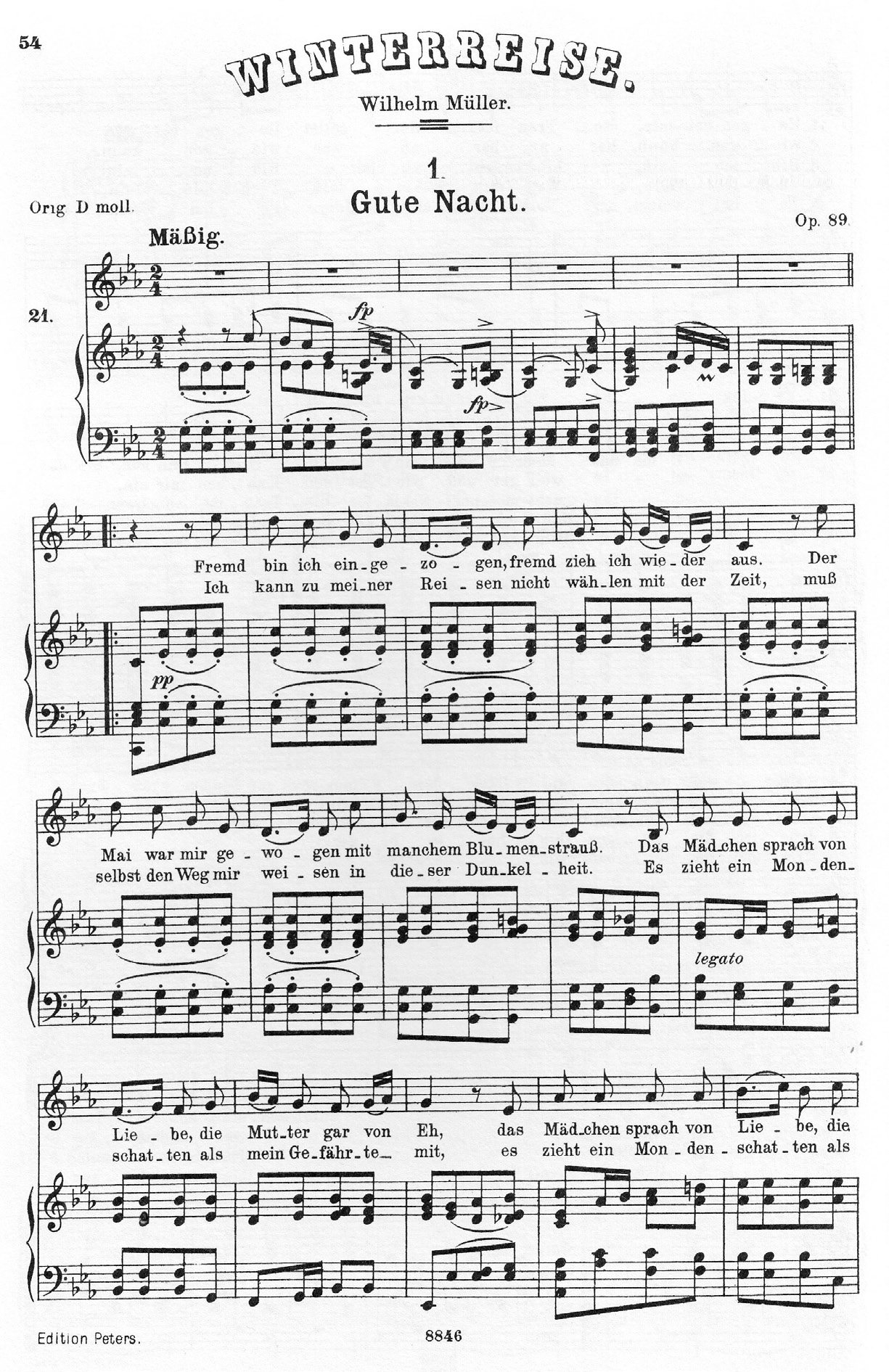

The recital this evening was given in a small hall, before an audience made up of Germans and Jews. Lucy arrived very early and was able to change her seat (which was near Auerbach’s) for one at the back of the house, in the shadow of a pillar, where she could feel very much alone. She had never heard Die Winterreise sung straight through as an integral work. For her it was being sung the first time, something newly created, and she attributed to the artist much that belonged to the composer. She kept feeling that this was not an interpretation, this was the thing itself, with one man and one nature behind every song. The singing was not dramatic, in any way she knew. Sebastian did not identify himself with this melancholy youth; he presented him as if he were a memory, not to be brought too near into the present. One felt a long distance between the singer and the scenes he was recalling, a long perspective.

This evening Lucy tried to give some attention to the accompanist—there was good reason, surely, if she were to attempt to take his place tomorrow! Even at the other concert she had felt that she had never heardanyone play for the voice so well. Die Krähe, Der Wegweiser . . . there was something uncanny in that young man’s short, insinuating fingers. She admired him, but she didn’t like him. Was she jealous, already? No, something in his physical personality set her on edge a little. He was picturesque—too picturesque. He had the very white skin that sometimes goes with red hair, and tonight, as he sat against an olive-green velvet curtain, his features seemed to disappear altogether. His face looked like a handful of flour thrown against the velvet. His head was rather flat behind the ears, and his red hair seemed to clasp it in a wreath of curls that were stiff but not tight. She thought she remembered plaster casts in the Art Museum with just such curls. For some reason she didn’t like the way he moved across the stage. His lameness gave him a weak, undulating walk, “like a rag walking,” she thought. It was contemptible to hold a man’s infirmity against him; besides, if this young man weren’t lame, she would not be going to Sebastian’s studio tomorrow,—she would never have met him at all. How strange it was that James Mockford’s bad hip should bring about the most important thing that had ever happened to her!

After the concert Paul Auerbach, in his old-fashioned dress coat and white lawn tie, came up to her. “I am going back to the artists’ room, Lucy. Would you like to go with me?”

She hesitated. “No, thank you, Mr. Auerbach. I’d rather not. Will he really expect me tomorrow, do you think?”

6

The next morning Lucy was walking across the city toward Michigan Avenue. She was happy, she was frightened,—couldn’t keep her attention on anything. Her mind had got away from her and was darting about in the sunlight, over the tops of the tall buildings. Exactly at ten o’clock she went into the Arts Building and told the hall porter she had an engagement with Mr. Sebastian. He rang for the elevator, and she was taken up to the sixth storey. When she lifted the brass knocker, Sebastian himself opened the door.

“I was expecting you,” he said with a nod. “I knew you were in town, for I saw you in my audience last night, hiding behind a pillar. Did you like the concert?” He took her coat from her and hung it up. “Better take off your hat, too; you’ll be more comfortable.”

The music room opened directly off the entry hall, with only a doorway between. As she walked into it, Lucy noticed it was a big room, full of sunlight, and that the general colour was dark red; the rugs and curtains and chairs. The piano stood at the front, between two windows.

Sebastian saw that she was not looking at anything; probably she was frightened again.

“Shall we begin? We can talk afterwards. We’ll work a little on the Elijah. I have to go to St. Paul to sing it with an oratorio society very soon, and I’ve not looked at it for a long while.”

When she sat down at the piano, he put the music on the rack, turning over the pages. “Before we begin with my part, we might run through the tenor’s aria, here. It’s much too high for me, of course, but I like to sing it.” He pointed to the page and began: “If with all your heart you truly seek Him.”

“That’s a nice introduction to the whole thing, isn’t it? Now we’ll take it up just here,” he leaned over her and indicated with his finger.

He walked up and down in his elkskin shoes as he sang, his hands in the pockets of his smoking-jacket. Lucy had no thought for anything but the score in front of her. An hour and a half went by very quickly. Just when she thought things were going better, he put his hand on her shoulder.

“Enough for today, Miss Gayheart. Very good for a first trial. Shall we begin at the same hour tomorrow? And don’t become agitated when you make mistakes. What I most want is elasticity. You must learn to catch ahint quickly in the tempi. When I’m eccentric, catch step with me. I have a reason, or think I have. Now suppose we sit down over here by the fire and have a glass of port and a biscuit. We’ve been working very hard.”

She rose and went to the chair he pointed out. She suddenly felt tired. Sebastian lowered the heavy window-shades a little, until the sunshine fell only on the rugs and the brass fire-irons. He brought a tray with a decanter and glasses and sat down opposite her, lounging back in his chair with his feet to the fire.

“Have you ever heard the Elijah well given, Miss Gayheart?”

Lucy told him she had never heard it given at all.

He smiled indulgently. “Mendelssohn is out of fashion just now. Who is the fashion? Debussy, I suppose? You’ve noticed that people are interested in music chiefly to have something to talk about at dinner parties?”

Lucy murmured she couldn’t say as to that; she didn’t go to dinner parties, and she didn’t know anyone in Chicago except Professor Auerbach and a few of his students.

“And in your own part of the country isn’t it so?”

“I think my father is the only person in our town who is much interested in music. He leads the town band and gives lessons on the clarinet.”

“Your father is a music-teacher?”

“Not exactly. He’s a watchmaker by trade, but he plays the clarinet and flute very well, and the violin a little.”

“German, of course? That’s good. A German watchmaker who plays the flute seems to me a comfortable sort of father to have.”

He asked her how she happened to come to Chicago, and to study with Auerbach. She felt that his questions were not perfunctory, that he really wanted to know something about her life, and she got over her shyness.

While they were talking, the outer door opened softly, and a little man in a stiffly starched white jacket and noiseless tennis shoes, carrying several coats on hangers, darted through the room and disappeared into the sleeping-chamber beyond.

“That is Giuseppe, my valet,” Sebastian explained. “Come in and see how well he does for me.” He opened the door and took Lucy into his sleeping-room. “Giuseppe, this is the Signorina who is coming to play for me until Mr. Mockford is better. I want her to see how we live.”

“Si, si, signore.” Giuseppe smiled eagerly and stepped back from the clothes-closet, pointing to the rows of coats and trousers very much as if he were a guide in a picture gallery. When he thought she had observed them sufficiently, he flourished his hand toward the dressing-table and toward a bed of faultless contour.

“Yes, he keeps everything very neat. If you went through my bureau drawers, you’d find them just like your own. He makes my breakfast too, and brings it up to me.”

Giuseppe stood holding his hands clasped in front of his stomach, smiling like a little boy being praised. His face seemed almost like a boy’s. But his hair, Lucy noticed, was thin and faded, and his high red forehead (shaped like a bowl) was seamed by deep lines from left to right. A moment later, when he had gone to the far end of the music room to put fresh coal on the fire, Lucy asked Sebastian whether Giuseppe had been with him long.

“I picked him up in London, on the way over. He used to be valet de chambre in a hotel in Florence. I’ve never had better service. Think of it, he has got all those lines on his forehead worrying about other people’s coats and boots and breakfasts. I haven’t a friend in the world who would do for me what that little man would.”

Something in the way he said this made Lucy feel a trifle downcast. She almost wished she were Giuseppe. After all, it was people like that who counted with artists—more than their admirers.

When she left the studio a few moments later she found the Italian in the little entrance hall, before a table drawer which was divided into compartments. Into these he was putting away gloves; into one white gloves, into anothertan, into another grey. A man must be rich and successful indeed to live in such beautiful order, she thought.

When she reached her own room after lunch, she looked about it with affection and compassion. She pulled down the shades, opened the window a little, and threw herself upon the bed, too tired to sit up and too much excited to sleep. Things she had scarcely noticed at the time came rushing through her mind: the dressing-gown thrown on a chair, the silver on the dressing-table, the spongy softness of the rose-coloured blankets the valet was smoothing on the bed, and those gloves in the table drawer. Evidently nothing ever came near Sebastian to tarnish his personal elegance. She had never known a man who lived like that.

Harry Gordon was rich, to be sure; he owned carriages and blooded horses, sleighs and guns, and he had his clothes made in Chicago. But his things stood out, and weren’t a part of himself. His overcoats were harsh to touch, his hats were stiff. He was crude, like everyone else she knew. An upstanding young man, they called him at home, easy and masterful in his own town, but in a big city he took on a certain self-importance, as if he were afraid of being ignored in the crowd. She remembered just how Sebastian looked when he stood against the light in his heelless shoes and old velvet jacket. Hewould be equal to any situation in the world. He had a simplicity that must come from having lived a great deal and mastered a great deal. If you brushed against his life ever so lightly it was like tapping on a deep bell; you felt all that you could not hear.

7

It was settled that, for the present, Lucy should go to the studio every day when Sebastian was in town. In the morning she awoke with such lightness of heart that it seemed to her she had been drifting on a golden cloud all night. After she had lain still for a few moments to feel the physical pleasure of coming up out of sleep, she would run down a cold hallway and take her bath before the other occupants on her floor were stirring. When she entered the bakery downstairs, the savour of coffee was delightful to her. Mrs. Schneff served the early comers herself, in a blue gingham dress and a white apron. She asked Lucy “how come” she ate more breakfast now than she used to. Lucy laughed and told her she was making more money now. “Dat is goot,” said the plump bakeress approvingly.

After breakfast Lucy went upstairs and put her room in order. She could never make her bed look so high and smooth as Giuseppe’s, but that was because she had no box-springs, or blankets soft as fur.

The weather was miraculous, for January. She always started very early for Michigan Avenue, and had an houror so to walk along the Lake front before she went into the Arts Building. There was very little ice in the water that January, and the blue floor of the Lake, wrinkled with gold, seemed to be the day itself, stretching before her unspent and beautiful. As she walked along, holding her muff against her cheek on the wind side, it was hard to believe there was anything in the world she could not have if she wanted it. The sharp air that blew off the water brought up all the fire of life in her; it was like drinking fire. She had to turn her back to it to catch her breath.

At ten o’clock she went into the studio and brought the freshness of the morning weather to a man who rose late and did not go abroad until noon. She warmed her hands at the coal grate while he finished his cigarette. If Sebastian had been slow in dressing, Giuseppe answered her knock, his dust-cloth on his arm, and hung up her coat, telling her that the maestro would be out subito, subito. He called her Signorina Lucia. After she and Sebastian set to work, Giuseppe went in to do the bedroom, leaving the door open a little so that he could listen.

One morning when Sebastian finished singing “It is enough . . . I am not better than my fathers,” Lucy turned impulsively on her stool to look at him. She never allowed herself to make any comment (she knew he wouldn’t like it), but often she had to make some bodily movement tobreak the tension. There in the doorway of the sleeping-chamber stood Giuseppe, his red hands crossed over his stomach, his head inclined, his sharp face and quick little eyes melted into repose and gravity. He caught up the laundry bag from behind the door, and pausing just a moment on the ball of his foot, looked Sebastian straight in the eye. “Ecco una cosa molto bella!” he brought out in a husky voice, before he vanished through the entry hall.

Lucy found she clung to Giuseppe as if he were a protector among things that were new and strange. Several times she met him in the street, going on errands in a grey overcoat much too long for him and a hard felt hat. On seeing her he would snatch off his hat, and his face, his whole body, indeed, would express astonishment and delight, as if it were wonderful, almost supernatural, that they should encounter one another thus.

Her acquaintance with Giuseppe progressed rapidly, but with Sebastian she seemed to get little further than on the first day. He kept well behind his courteous, half-playful, and rather professional manner,—a manner so perfected that it could go on representing him when he himself was either lethargic or altogether absent. His amiability puzzled Lucy, and rather discouraged her.

When she used to see Sebastian by chance occasionally, on the street or in the Park, his face seemed to herforbidding. Sometimes she thought it stern and indifferent, but more than once it had struck her as melancholy. In the studio there was none of that. He met her with a smile, and throughout the morning was friendly and affable. Yet she went away feeling that the other man, whom she used to see secretly, was his real self.

Trivial, accidental things gradually broke down his reserve. Once, as she was coming down the Lake side of Michigan Avenue, just before she crossed to the Arts Building, she happened to glance up, and saw Sebastian standing at an open window, looking down at her. He leaned out a little and waved his hand. After that he was at the window almost every morning. This made a difference in the way he greeted her at the door; it was as if they had already met in the street and were coming into the studio together. There was a keener interest in his eyes when he took her hand, and he looked down into her face as if she were bringing him something that pleased him. He once told her so, indeed. She had just put her hat on the hall table. He took it up, stroked the brown fur, and ran his finger-tips along the slender, drooping red feather.

“You know, I like to see this little red feather coming down the street. I watch for it, and should be terribly disappointed if it didn’t come. You seem to find walkingin the cold the most delightful thing imaginable. Montaigne says somewhere that in early youth the joy of life lies in the feet. You recall that passage to me, Lucy. I had forgotten it.”

He often told her amusing stories. It was not a habit of his, but he liked to hear her laugh. He never remarked upon this (compliments, he believed, had a disastrous effect upon any charming natural expression), but he provoked it for his own pleasure. A beautiful laugh was rare, certainly; after she left him he used to screw up his eyes and try to imitate it in his mind. Nothing about her drew him to her so much as this purely unconscious physical response.

Lucy knew more or less about Sebastian’s outside life from his telephone conversations. When she left the piano, he always made her rest before she went out into the cold. He sat down and talked to her, but they were very often interrupted by the telephone,—the house operator put no calls through until after eleven-thirty. Lucy could not help hearing his replies and learning something about his engagements, his business affairs, who his friends were. With women his talk was usually gentle and soothing, as if the lady at the other end were in a flurry, or very insistent. He told the most transparent lies in refusing invitations, didn’t seem to try to makethem plausible. But he always said something agreeable; asked to be remembered to the lady’s charming daughter, or thanked her for recommending a book which he had liked very much. Every day his concert agent, Morris Weisbourn, called him up as soon as his wire was open. Their talk was usually very brief. But one morning when he answered Weisbourn’s call Lucy heard a sudden change in Sebastian’s voice.

“What’s that, Morris? When did this letter come? . . . No, she wrote me nothing about it. We don’t discuss business matters in our correspondence, that is what you are for. . . . Send a draft for the amount she mentions, and get it off today, not later. . . . Of course I can. Simply let the bills go over. . . . Very well, then meet me at the Auditorium for lunch, and I’ll write a cheque for it.”

When he came back from the telephone he lit another cigarette and took up the story he had been telling her about his first meeting with Debussy. But there was something bleak and unnatural in his smile, and Lucy hurried away.

She knew, as well as if a name had been mentioned, that the woman who had written for money was Mrs. Sebastian, and she thought it a shame. He always spoke of his wife in a very chivalrous way, and admiringly. She had heard him explain over the telephone, to a friendjust arrived from the Orient, that Mrs. Sebastian was not with him because she dreaded the Chicago winter climate. When he happened to tell Lucy about something he and his wife had done or seen, he seemed to recall it with pleasure, became animated and gay. But she felt sure that things were not like that with them now. Perhaps this was why he was unhappy.

His manner, when she was with him, was that of a man who has an easy, if somewhat tolerant, enjoyment of life. Some of the people who telephoned him he seemed really fond of, and she knew that he was attached to James Mockford, “one of the few friends who have lasted through time and change,” as he once remarked. But he seemed very careful never to come too close to people. She believed he was disappointed in something—or in everything.

She had been playing for him nearly three weeks, when quite by accident she saw again that side of him which his genial manner usually covered. One evening Giuseppe knocked at her door, bringing a note from Sebastian. He would not be at the studio tomorrow morning, as he had to attend the funeral services of a friend.

Lucy looked through the evening paper and found that Madame Renée de Vignon, a French singer, returning from California, had died in her hotel last night afteran illness of only twenty-four hours. There would be a funeral service for her at eleven o’clock in the small Catholic church near her hotel. Afterwards her body would be sent back to France.

The next morning, a little before the hour announced, Lucy stole into the church. There were not a great many people there, and in the dusky light she easily found Sebastian. He was kneeling, with his hand over his face. When the organ began to play softly, and the doors were opened and held back to admit the pallbearers, he lifted his head and turned in his seat to face the coffin, carried into the church on the shoulders of six men. A company of priests and censer-bearers went with it up the aisle toward the altar. As it moved forward, Sebastian’s eyes never left it; turning his head slowly, he followed it with a look that struck a chill to Lucy’s heart. It was a terrible look; anguish and despair, and something like entreaty. All faces were turned reverently toward the procession, but his stood out from the rest with a feeling personal and passionate. He had forgotten himself, forgotten where he was and that there were people who might stare at him. It seemed to Lucy that a wave of black despair had swept into the church, carrying him and that black coffin up the aisle together, while the clergy and worshippers were unconscious of it. Had this woman been a verydear friend? Or was it death itself that seemed horrible to him—death in a foreign land, in a hotel, far from everything one loved?

During the service he remained kneeling. From time to time he drew out a handkerchief and wiped his forehead, but he did not lift his face or his broad black shoulders until the coffin was carried back toward the door. As it passed him, he gave it one long, dull look, out of half-closed eyes. He was among the first to leave the church. When Lucy reached the steps outside, she could see him far down the street, walking rapidly, his back straight and stiff.

Once before, in November (how long ago it seemed!), she had seen him coming out of a church, the Cathedral, when she happened to be passing. He merely came out of the door, down the steps, and turned straight north, without looking about for a cab as he usually did. She felt sure, by the look on his face, that he was coming from some religious observance. She went into the Cathedral; there was no service going on, there were not a dozen people in the building; but she knew that he had been there with a purpose that had to do with the needs of his soul.

8

Usually Sebastian and Mockford went out of town at the end of the week to give a recital somewhere. Sebastian often telephoned the young man, making appointments for the evening or afternoon, but Mockford never dropped in upon them in the morning, and Lucy was glad of it. She had never met him, or seen him except on the concert stage. One morning when Sebastian handed her some songs from Die Winterreise and asked her to look them over, she sighed and shook her head.

“It won’t be much use, I’m afraid. After hearing Mr. Mockford play them, I think the best I can do is just to read them off.”

Sebastian laughed. “Jimmy is a little genius with those, isn’t he? I doubt if Schubert ever heard them played so well. In his mind, perhaps. Jimmy’s not especially good with Mozart or the Italian composers; but in the true German Lieder, whatever he does seems to be right. I’ve got a great many hints from him.”

On the day Sebastian was to leave for his concert engagements in Minnesota and Wisconsin, Lucy went to the studio to tell him good-bye. It was Mockford whoopened the door for her and asked her to come in. She drew back and would have run away if she could.

“No, come in, Miss Gayheart. It is Miss Gayheart, isn’t it? Clément has gone down to Allston’s studio for a moment. Please allow me.” He took her coat, waited for her to go into the music room, and limped in after her.

While he was pulling up a chair for her and poking the coal fire, she saw him by daylight for the first time. She had thought of him as a very young man, a youth, indeed. This morning he did not seem young, but wiry and rather hard. Even his white skin looked harder, somewhat rubbery, and there was a yellow glint in it where the razor had not bit close. His copper-red hair fitted his head so snugly that it might have been a well-made wig.

“I’m glad to meet you, Miss Gayheart. Glad to have an opportunity to thank you for filling in.” He sat down and looked at Lucy, looked her over deliberately, and she looked at him. When they had met at the door, the light was behind him and she could not see his eyes. They might be called hazel, perhaps, but this morning they were frankly green; a cool, sparkling green, with something restless in them. He was the first to break down in the searching look they gave each other. He rose quickly and softly and lowered the window-shades a little. On the way back to his chair, he began talking:

“I’m very upset to be fussing with doctors and dropping out like this. Neither of us had looked forward to this American season with much pleasure. However, he seems to be getting on very well with you.”

“I don’t know as to that. I’ve no experience. I do the best I can.” Lucy could not tell whether he meant to be patronizing, or whether he was merely ill at ease. She felt that he had disliked her instantly, as she had him.

“Oh, he rather fancies breaking in a new person. The difficulty is that Clément can never work with anyone who isn’t personally sympathetic to him. The odds are always against our being able to pick up one of that sort on short notice.”

Lucy flushed, but said nothing. She was looking at his white, freckled hands, lying on the red velvet arms of the chair. The fingers were square and unusually short for a pianist, but the breadth of palm was remarkable.

“He gives a good account of you”—Mockford shot her a green glance—“ and since you do get on, it may be a good thing for him—a change. He doesn’t find much to divert him here. The truth is, he’s bored to death. I wasn’t for his coming over at all. But he needs the money. And he’d be bored anywhere just now. It’s only fair to say that you’re not hearing the artist we know at home and on the Continent.”

“You have been with him a long while, Mr. Mockford?”

“Yes, off and on, a long while,” he said carelessly. “There have been interregnums. Mrs. Sebastian takes a fancy to a new pianist now and then, and Clément tries him out. So far they’ve not been altogether satisfactory.” “She is musical then, Mrs. Sebastian?”

“Oh, naturally! She is one of Sir Robert Lester’s daughters.” He glanced at Lucy to see whether this enlightened her. It did not, so he murmured: “He was one of our best conductors. The pianist has to make it go with her as well as with Clément, if you mean that.”

Lucy coloured again. “No, I did not mean that. I only wanted to know if she is much interested in—in that side of him.”

“In all sides, I should say. She was accustomed to direct things in her father’s household. It becomes her very well.” He wrinkled up his short nose and squinted as if a strong light had been flashed in his face.

There was a kind of fascination about Mockford, Lucy thought. He looked as if he were made up for the stage, yet there he sat in perfectly conventional clothes, except for a green silk shirt and green necktie. He couldn’t help looking theatrical; he was made so, and she couldn’t tell whether or not he liked being unusual. His manner was a baffling mixture of timidity and cheek. One thing wasclear; he was uncomfortable in her company, and certainly she was in his. She was about to rise when she heard a fumbling at the door. It was not Sebastian, however, but the hall porter, with the railway tickets. He gave them to Mockford, told him at what hour their train left, and just when he would have a cab downstairs for them.