Sapphira and the Slave Girl

The Willa Cather Scholarly Edition

Susan J. Rosowski, 1984-2004

Charles W. Mignon

John J. Murphy

Kari A. Ronning

David Stouck

Gary Moulton

Paul A. Olson

James Woodress

University of Nebraska PressLincoln, 2009

CONTENTS

Preface

The objective of the Willa Cather Scholarly Edition is to provide to readers—present and future—various kinds of information relevant to Willa Cather’s writing, obtained and presented according to the highest scholarly standards: a critical text faithful to her intention as she prepared it for the first edition, a historical essay providing relevant biographical and historical facts, explanatory notes identifying allusions and references, a textual commentary tracing the work through its lifetime and describing Cather’s involvement with it, and a record of changes in the text’s various editions. This edition is distinctive in the comprehensiveness of its apparatus, especially in its inclusion of extensive explanatory information that illuminates the fiction of a writer who drew so extensively upon actual experience, as well as the full textual information we have come to expect in a modern critical edition. It thus connects activities that are too often separate —literary scholarship and textual editing.

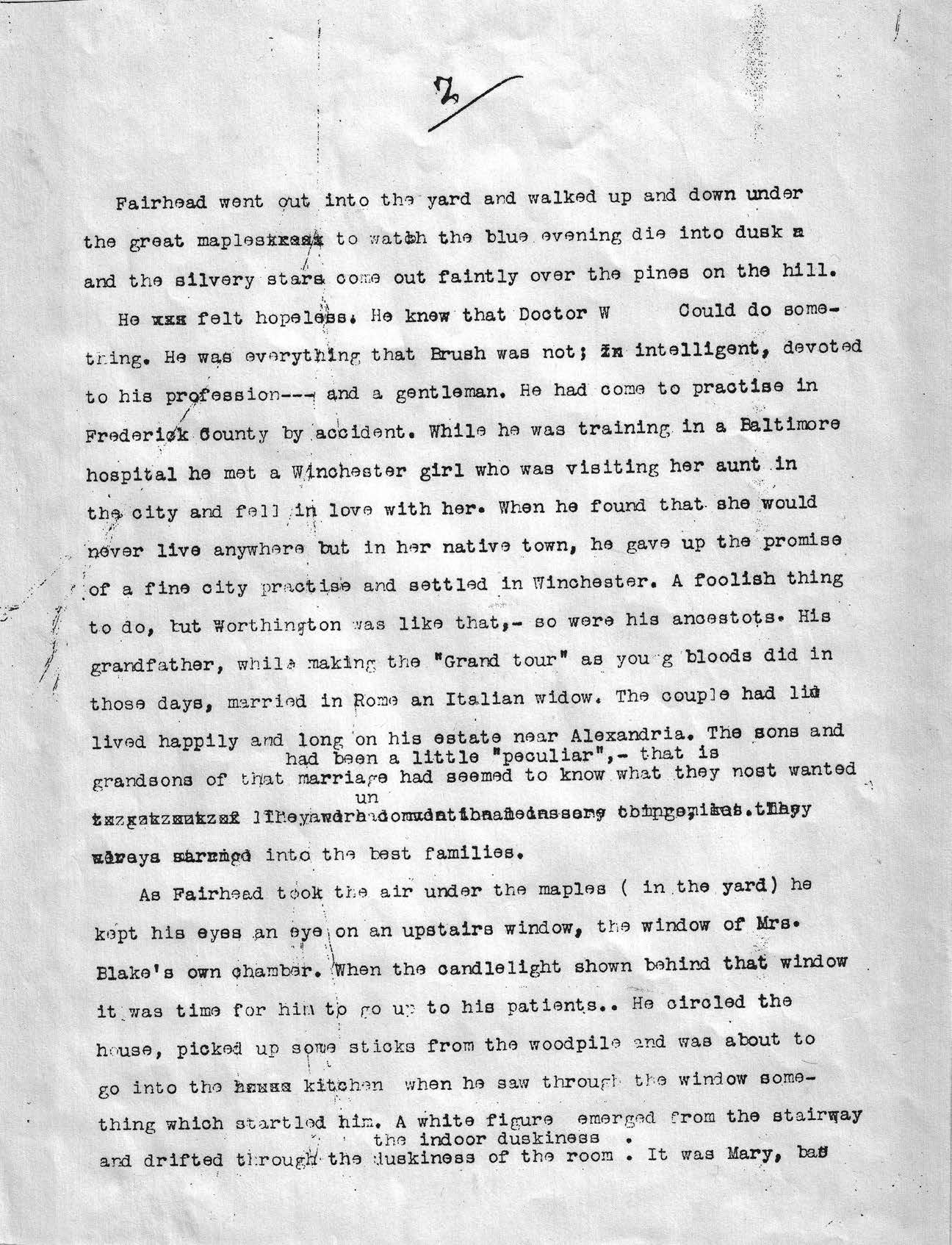

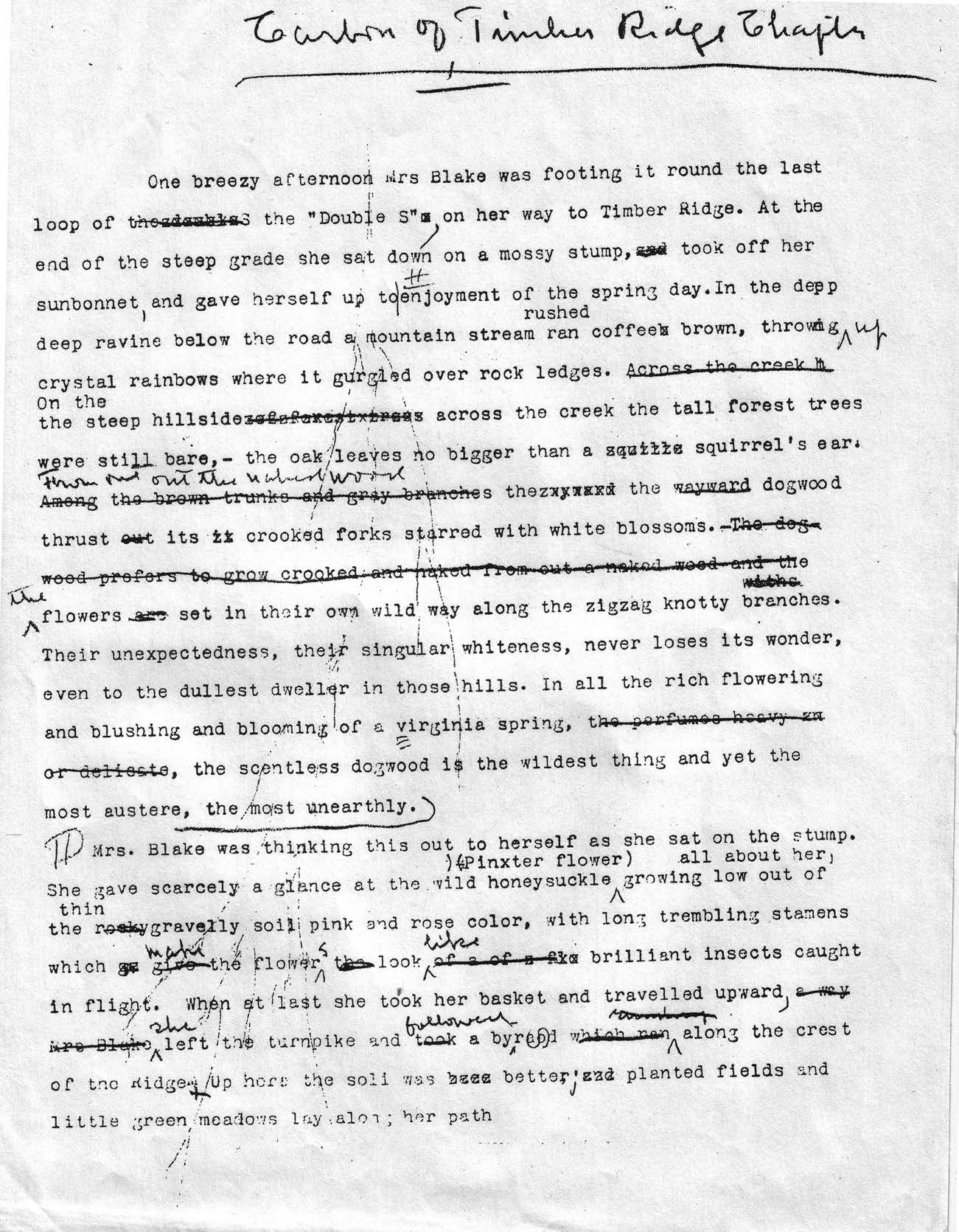

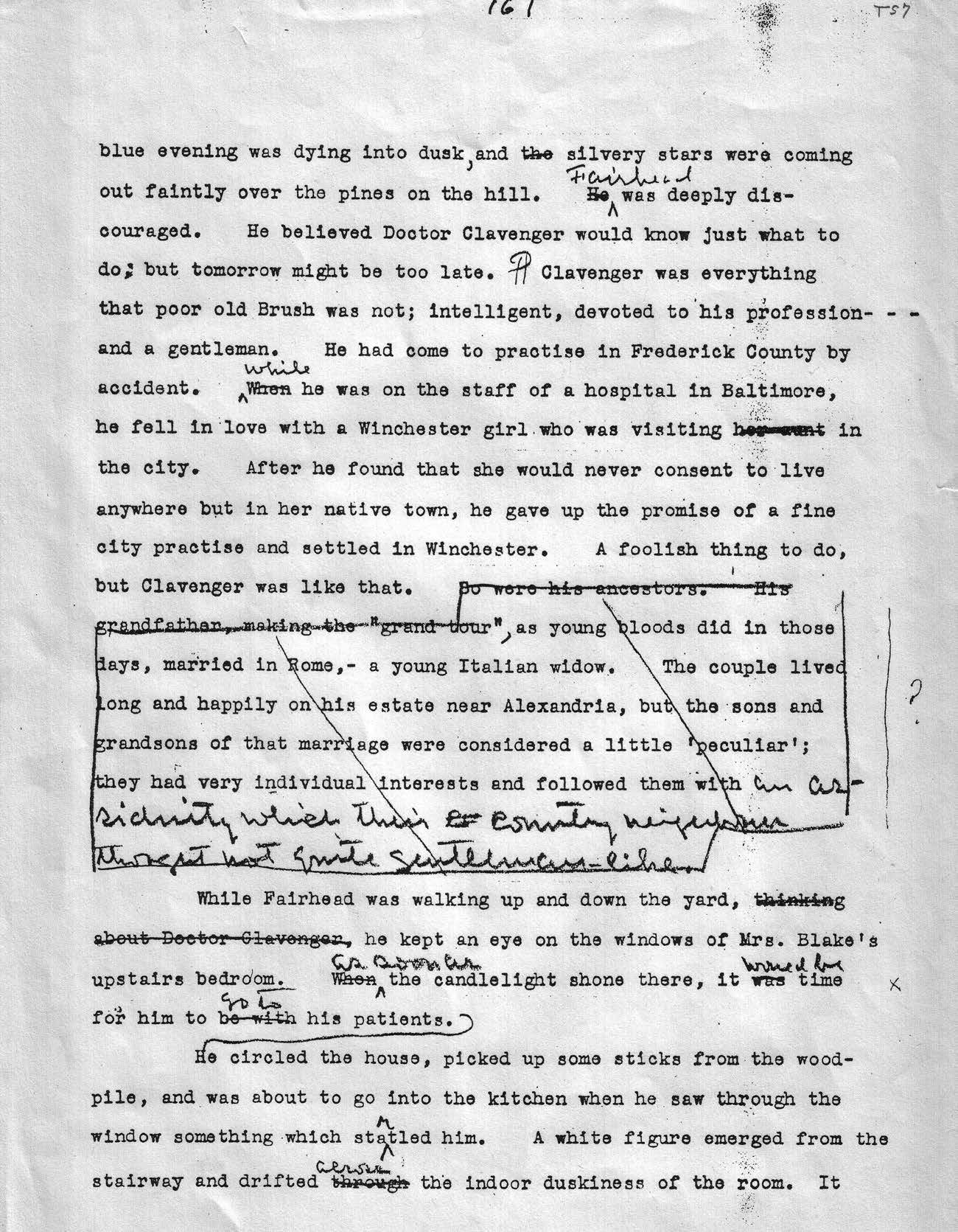

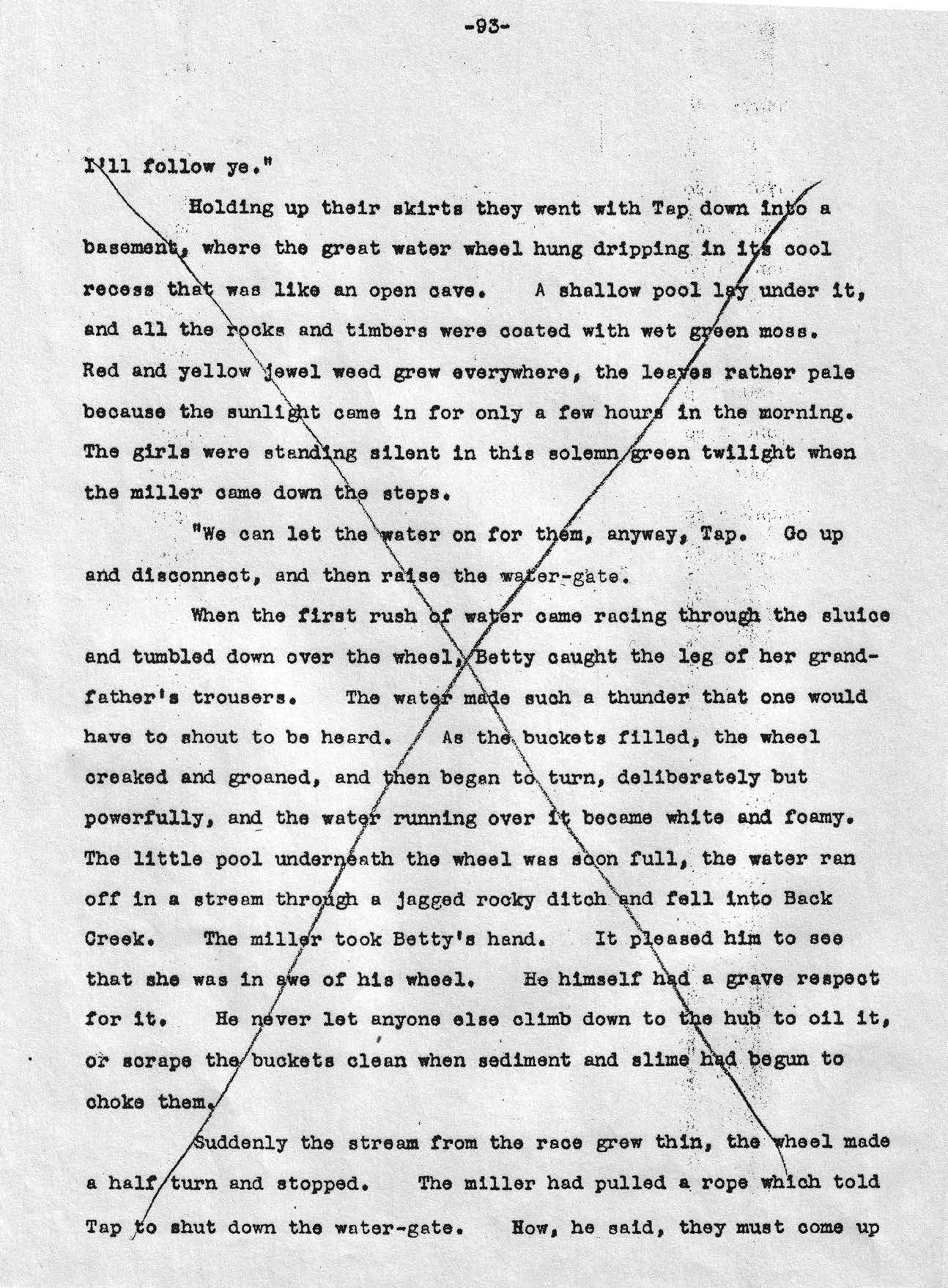

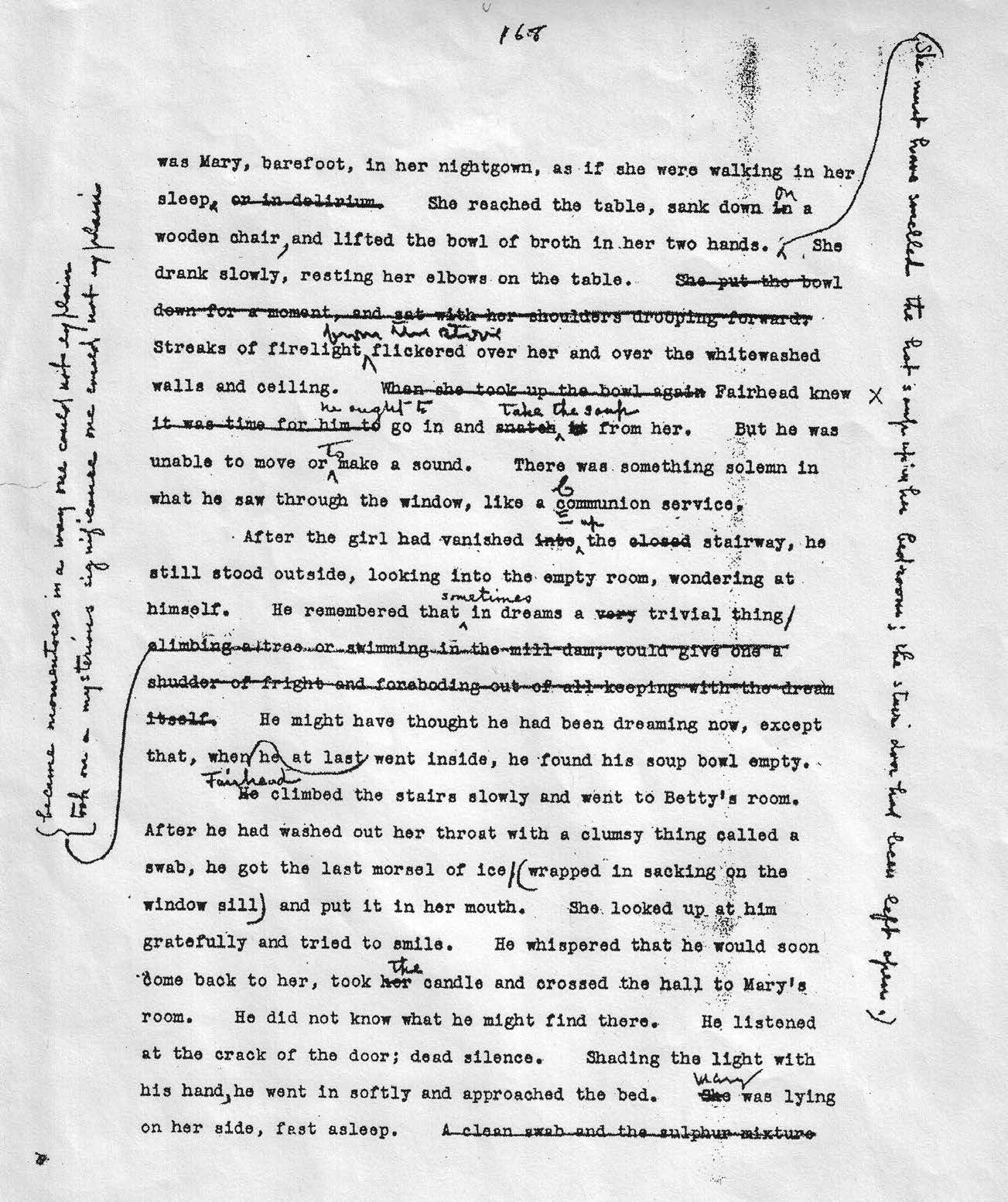

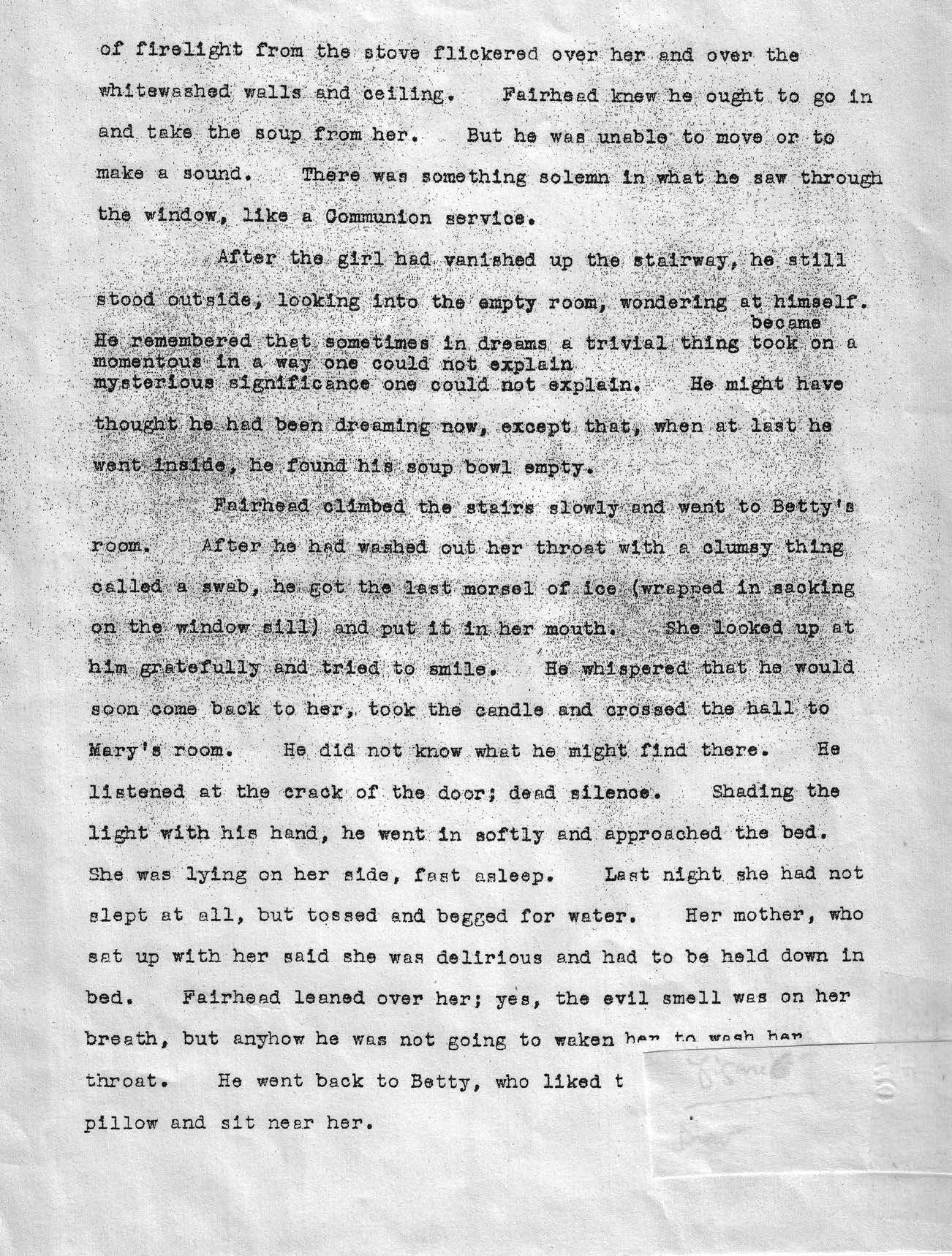

Editing Cather’s writing means recognizing that Cather was as fiercely protective of her novels as she was of her private life. She suppressed much of her early writing and dismissed serial publication of her later work, discarded manuscripts and proofs, destroyed letters, and included in her will a stipulation against publication of her private papers. Yet the record remains surprisingly full. Manuscripts, typescripts, and proofs of some texts survive with corrections and revisions in Cather’s hand; serial publications provide final "draft" versions of texts; correspondence with her editors and publishers helps clarify her intention for a work, and publishers’ records detail each book’s public life; correspondence with friends and acquaintances provides an intimate view of her writing; published interviews with and speeches by Cather provide a running commentary on her career; and through their memoirs, recollections, and letters, Cather’s contemporaries provide their own commentary on circumstances surrounding her writing.

In assembling pieces of the editorial puzzle, we have been guided by principles and procedures articulated by the Committee on Scholarly Editions of the Modern Language Association. Assembling and comparing texts demonstrated the basic tenet of the textual editor—that only painstaking collations reveal what is actually there. Scholars had assumed, for example, that with the exception of a single correction in spelling, O Pioneers! passed unchanged from the 1913 first edition to the 1937 Autograph Edition. Collations revealed nearly a hundred word changes, thus providing information not only necessary to establish a critical text and to interpret how Cather composed but also basic to interpreting how her ideas about art changed as she matured.

Cather’s revisions and corrections on typescripts and page proofs demonstrate that she brought to her own writing her extensive experience as an editor. Word changes demonstrate her practices in revising; other changes demonstrate that she gave extraordinarily close scrutiny to such matters as capitalization, punctuation, paragraphing, hyphenation, and spacing. Knowledgeable about production, Cather had intentions for her books that extended to their design and manufacture. For example, she specified typography, illustrations, page format, paper stock, ink color, covers, wrappers, and advertising copy.

To an exceptional degree, then, Cather gave to her work the close textual attention that modern editing practices respect, while in other ways she challenged her editors to expand the definition of "corruption" and "authoritative" beyond the text, to include the book’s whole format and material existence. Believing that a book’s physical form influenced its relationship with a reader, she selected type, paper, and format that invited the reader response she sought. The heavy texture and cream color of paper used for O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, for example, created a sense of warmth and invited a childlike play of imagination, as did these books’ large, dark type and wide margins. By the same principle, she expressly rejected the anthology format of assembling texts of numerous novels within the covers of one volume, with tight margins, thin paper, and condensed print.

Given Cather’s explicitly stated intentions for her works, printing and publishing decisions that disregard her wishes represent their own form of corruption, and an authoritative edition of Cather must go beyond the sequence of words and punctuation to include other matters: page format, paper stock, typeface, and other features of design. The volumes in the Cather Edition respect those intentions insofar as possible within a series format that includes a comprehensive scholarly apparatus. For example, the Cather Edition has adopted the format of six by nine inches, which Cather approved in Bruce Rogers’s elegant work on the 1937 Houghton Mifflin Autograph Edition, to accommodate the various elements of design. While lacking something of the intimacy of the original page, this size permits the use of large, generously leaded type and ample margins—points of style upon which the author was so insistent. In the choice of paper we have deferred to Cather’s declared preference for a warm, cream antique stock.

Today’s technology makes it difficult to emulate the qualities of hot-metal typesetting and letterpress printing. In comparison, modern phototypesetting printed by offset lithography tends to look anemic and lacks the tactile quality of type impressed into the page. The Linotype Caslon type employed in the original edition of Sapphira and the Slave Girl, were it available for phototypesetting, would hardly survive the transition. Instead, we have chosen Linotype Janson Text, a modern rendering of the type used by Rogers. The subtle adjustments of stroke weight in this reworking do much to retain the integrity of earlier metal versions. Therefore, without trying to replicate the design of single works, we seek to represent Cather’s general preferences in a design that encompasses many volumes.

In each volume in the Cather Edition, the author’s specific intentions for design and printing are set forth in textual commentaries. These essays also describe the history of the texts, identify those that are authoritative, explain the selection of copy-texts or basic texts, justify emendations of the copy-text, and describe patterns of variants. The textual apparatus in each volume—lists of variants, emendations, explanations of emendations, and end-of-line hyphenations— completes the textual story.

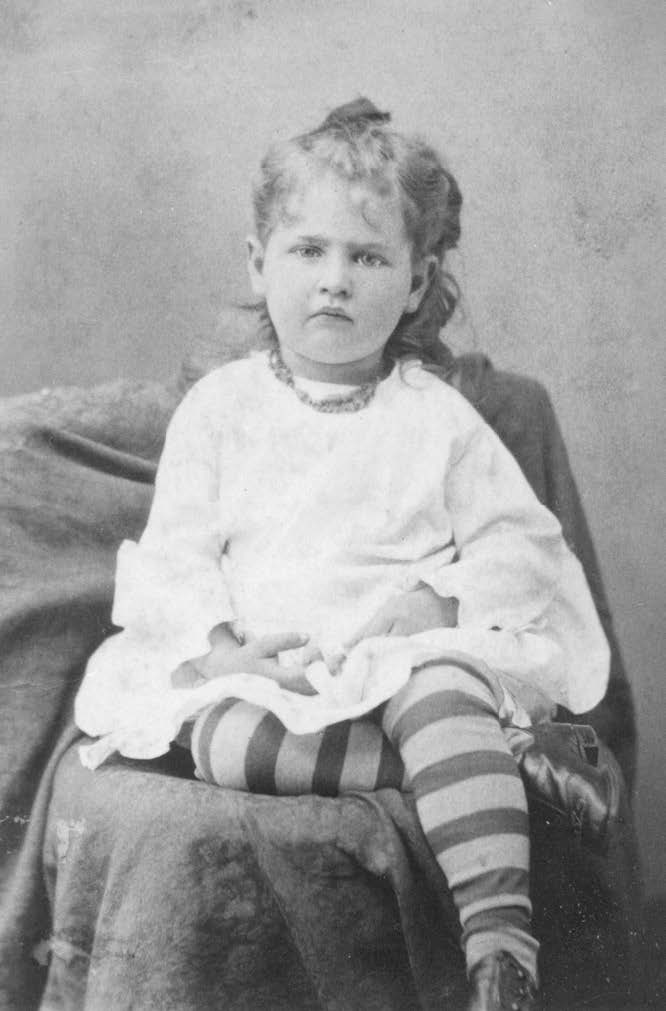

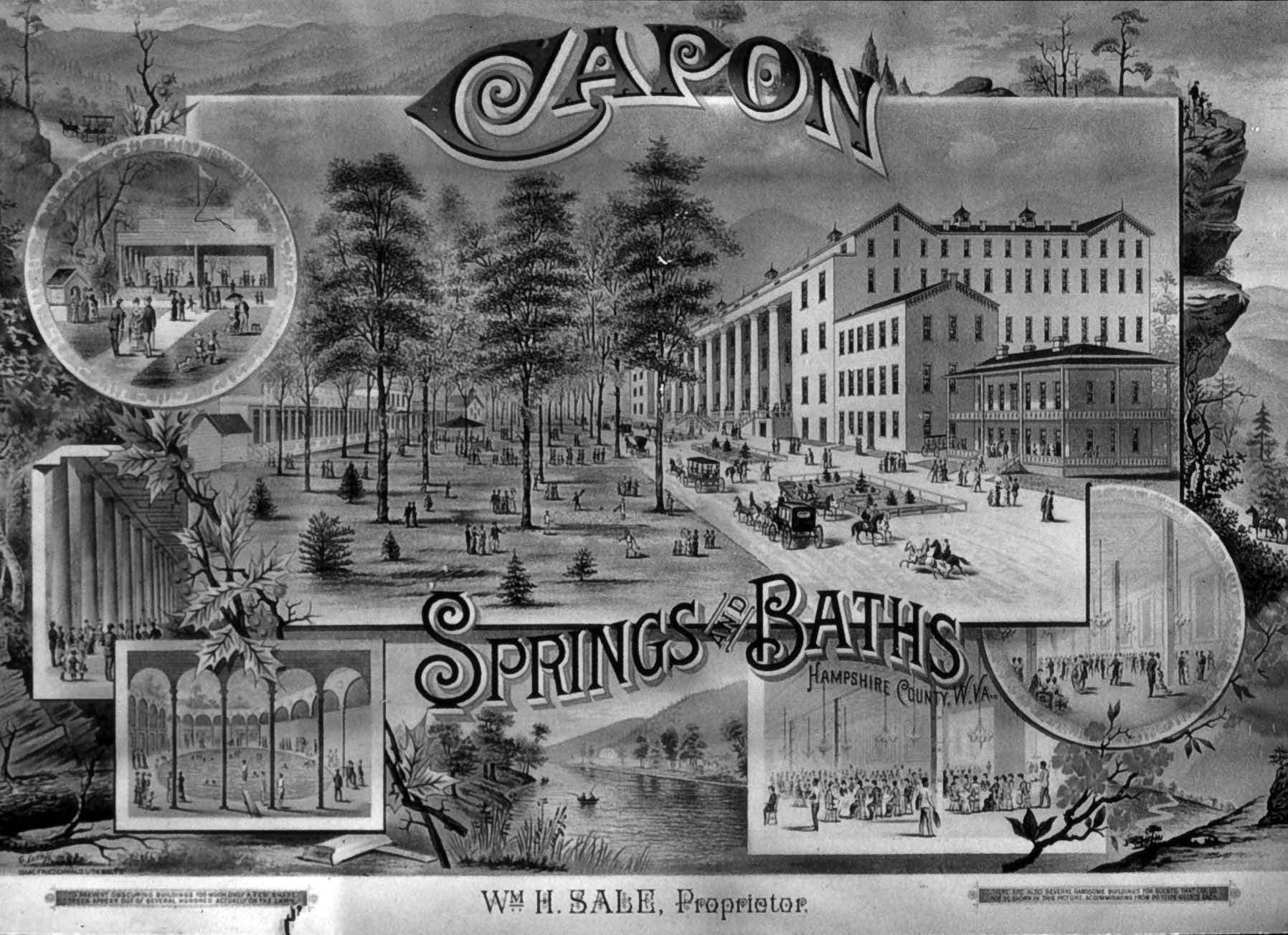

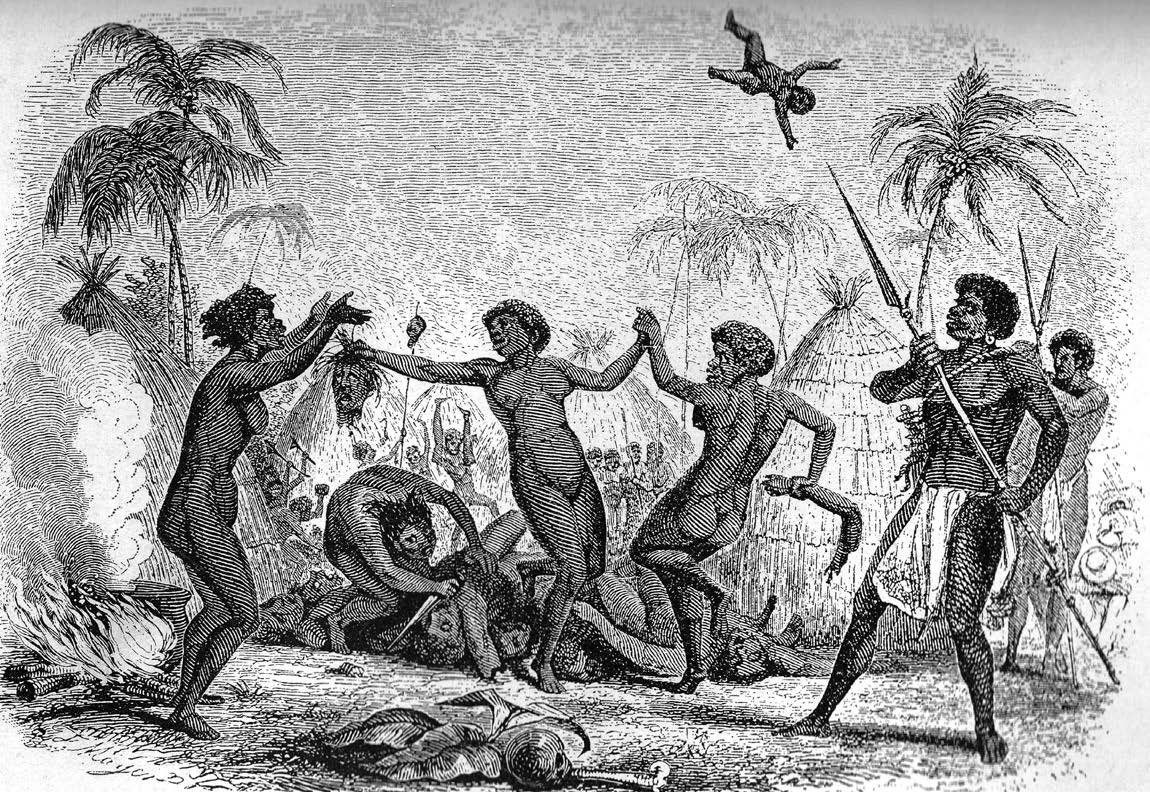

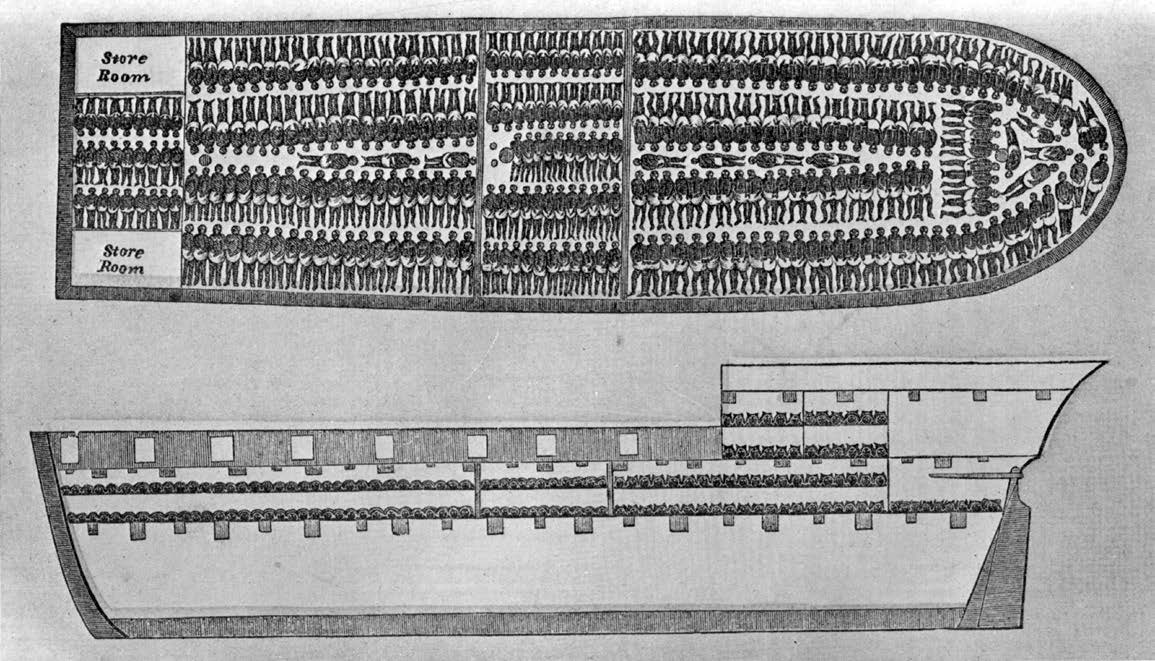

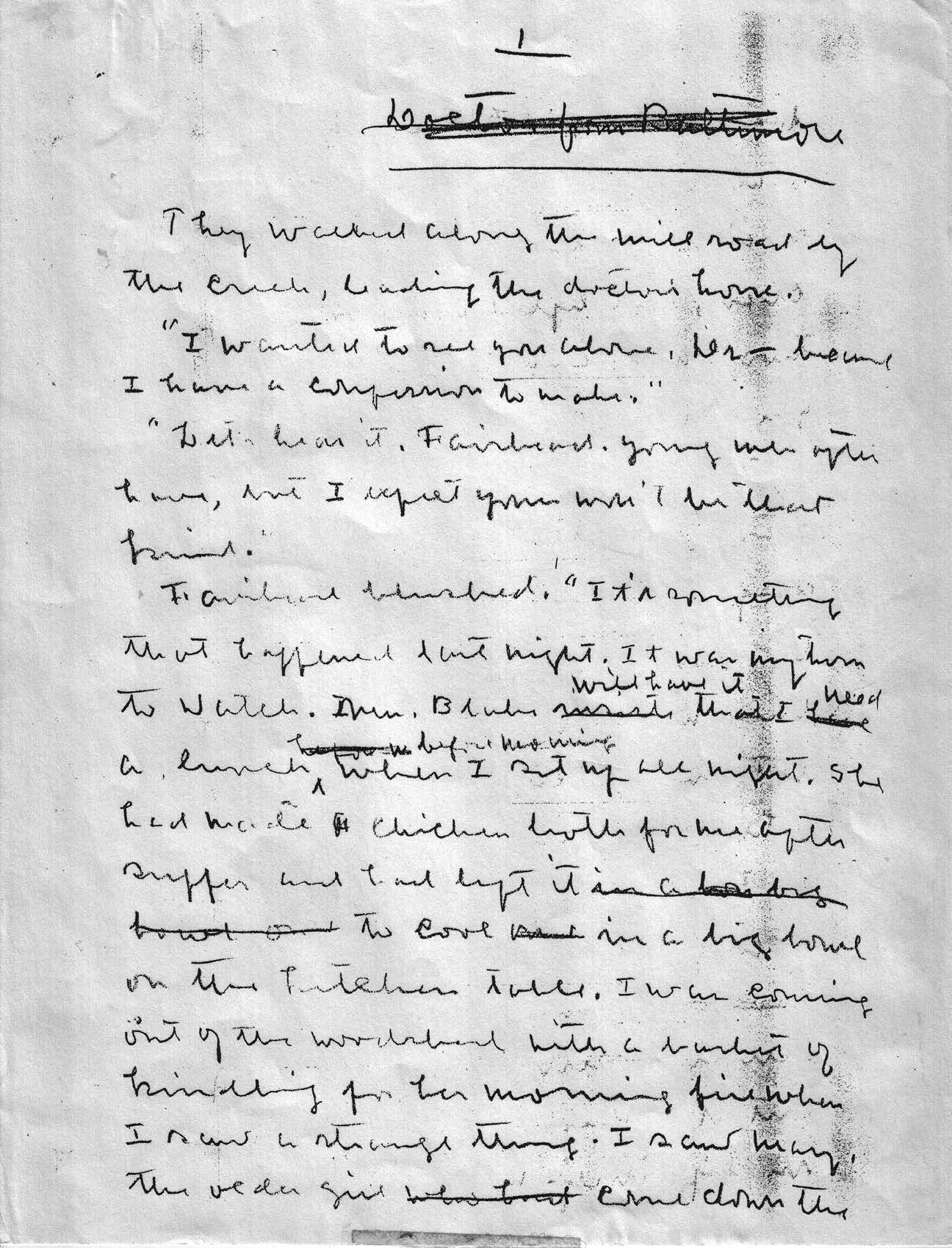

Historical essays provide essential information about the genesis, form, and transmission of each book, as well as supply its biographical, historical, and intellectual contexts. Illustrations supplement these essays with photographs, maps, and facsimiles of manuscript, typescript, or typeset pages. Finally, because Cather in her writing drew so extensively upon personal experience and historical detail, explanatory notes are an especially important part of the Cather Edition. By providing a comprehensive identification of her references to flora and fauna, to regional customs and manners, to the classics and the Bible, to popular writing, music, and other arts—as well as relevant cartography and census material—these notes provide a starting place for scholarship and criticism on subjects long slighted or ignored.

Within this overall standard format, differences occur that are informative in their own right. The straightforward textual history of O Pioneers! and My Ántonia contrasts with the more complicated textual challenges of A Lost Lady and Death Comes for the Archbishop; the allusive personal history of the Nebraska novels, so densely woven that My Ántonia seems drawn not merely upon Anna Pavelka but upon all of Webster County, contrasts with the more public allusions of novels set elsewhere. The Cather Edition reflects the individuality of each work while providing a standard reference for critical study.

Susan J. Rosowski

General Editor, 1984–2004

Guy J. Reynolds

General Editor, 2004–

CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

Sapphira and her Household

BOOK I

I

The Breakfast Table, 1856

Henry Colbert, the miller, always breakfasted with his wife—beyond that he appeared irregularly at the family table. At noon, the dinner hour, he was often detained down at the mill. His place was set for him; he might come, or he might send one of the mill-hands to bring him a tray from the kitchen. The Mistress was served promptly. She never questioned as to his whereabouts.

On this morning in March 1856, he walked into the dining-room at eight o’clock,—came up from the mill, where he had been stirring about for two hours or more. He wished his wife good-morning, expressed the hope that she had slept well, and took his seat in the high-backed armchair opposite her. His breakfast was brought in by an old, white-haired coloured man in a striped cotton coat. The Mistress drew the coffee from a silver coffee urn which stood on four curved legs. The china was of good quality (as were all the Mistress’s things); surprisingly good to find on the table of a country miller in the Virginia backwoods. Neither the miller nor his wife was native here: they had come from a much richer county, east of the Blue Ridge. They were a strange couple to be found on Back Creek, though they had lived here now for more than thirty years.

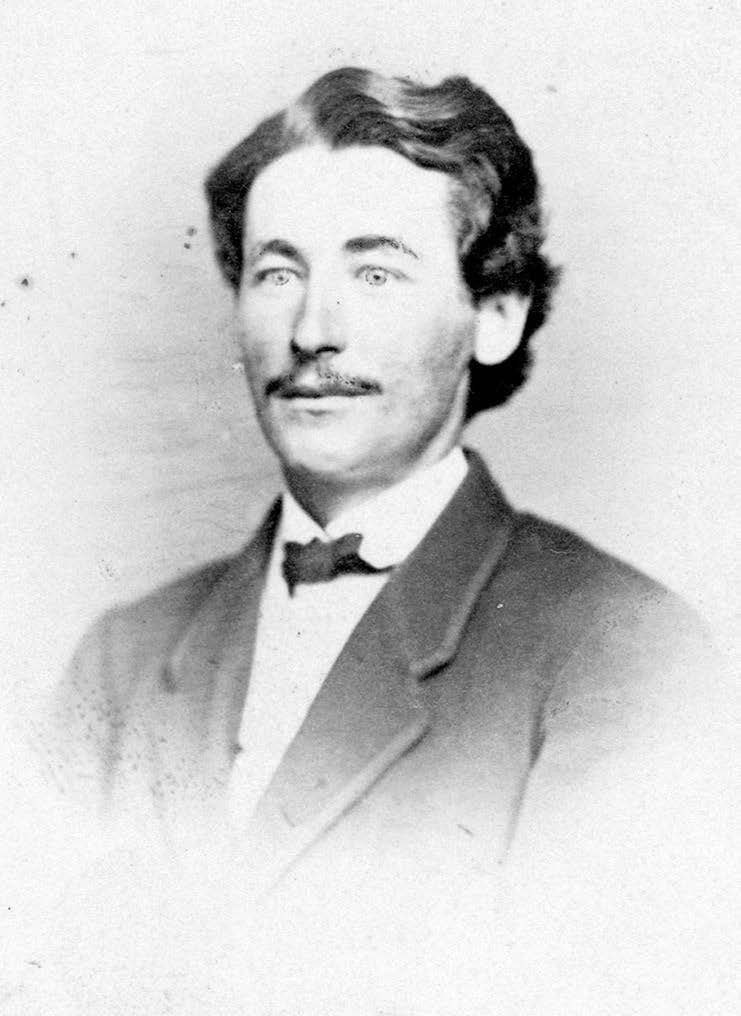

The miller was a solid, powerful figure of a man, in whom height and weight agreed. His thick black hair was still damp from the washing he had given his face and head before he came up to the house; it stood up straight and bushy because he had run his fingers through it. His face was full, square, and distinctly florid; a heavy coat of tan made it a reddish brown, like an old port. He was clean-shaven,—unusual in a man of his age and station. His excuse was that a miller’s beard got powdered with flour-dust, and when the sweat ran down his face this flour got wet and left him with a beard full of dough. His countenance bespoke a man of upright character, straightforward and determined. It was only his eyes that were puzzling; dark and grave, set far back under a square, heavy brow. Those eyes, reflective, almost dreamy, seemed out of keeping with the simple vigour of his face. The long lashes would have been a charm in a woman.

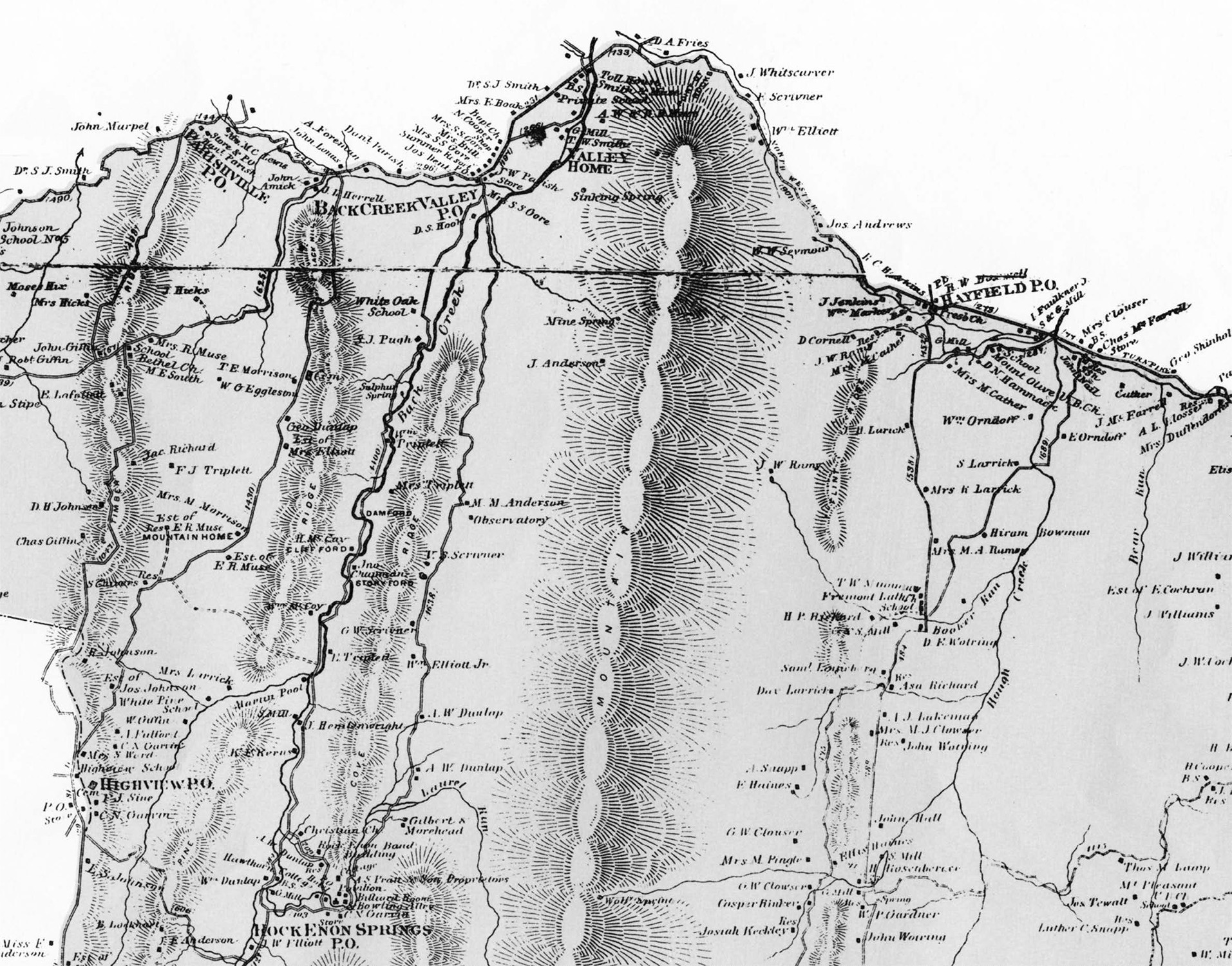

Colbert drove his mill hard, gave it his life, indeed. He was noted for fair dealing, and was trusted in a community to which he had come a stranger. Trusted, butscarcely liked. The people of Back Creek and Timber Ridge and Hayfield never forgot that he was not one of themselves. He was silent and uncommunicative (a trait they didn’t like), and his lack of a Southern accent amounted almost to a foreign accent. His grandfather had come over from Flanders. Henry was born in Loudoun County and had grown up in a neighbourhood of English settlers. He spoke the language as they did, spoke it clearly and decidedly. This was not, on Back Creek, a friendly way of talking.

His wife also spoke differently from the Back Creek people; but they admitted that a woman and an heiress had a right to. Her mother had come out from England— a fact she never forgot. How these two came to be living at the Mill Farm is a long story—too long for a breakfast-table story.

The miller drank his first cup of coffee in silence. The old black man stood behind the Mistress’s chair.

"You may go, Washington," she said presently. While she drew another cup of coffee from the urn with her very plump white hands, she addressed her husband: "Major Grimwood stopped by yesterday, on his way to Romney. You should have come up to see him."

"I couldn’t leave the mill just then. I had customers who had come a long way with their grain," he replied gravely.

"If you had a foreman, as everyone else has, you would have time to be civil to important visitors."

"And neglect my business? Yes, Sapphira, I know all about these foremen. That is how it is done back in Loudoun County. The boss tells the foreman, and the foreman tells the head nigger, and the head nigger passes it on. I am the first miller who has ever made a living in these parts."

"A poor one at that, we must own," said his wife with an indulgent chuckle. "And speaking of niggers, Major Grimwood tells me his wife is in need of a handy girl just now. He knows my servants are well trained, and he would like to have one of them."

"He must know you train your servants for your own use. We don’t sell our people. You might ring for some more bacon. I seem to feel hungry this morning."

She rang a little clapper bell. Washington brought the bacon and again took his place behind his mistress’s large, cumbersome chair. She had been sitting in a muse while he served. Now, without speaking to him, she put out her plump hand in the direction of the door. The old man scuttled off in his flapping slippers.

"Of course we don’t sell our people," she agreed mildly. "Certainly we would never offer any for sale. But to oblige friends is a different matter. And you’ve oftensaid you don’t want to stand in anybody’s way. To live in Winchester, in a mansion like the Grimwoods’—any darky would jump at the chance."

"We have none to spare, except such as Major Grimwood wouldn’t want. I will tell him so."

Mrs. Colbert went on in her bland, considerate voice: "There is my Nancy, now. I could spare her quite well to oblige Mrs. Grimwood, and she could hardly find a better place. It would be a fine opportunity for her."

The miller flushed a deep red up to the roots of his thick hair. His eyes seemed to sink farther back under his heavy brow as he looked directly at his wife. His look seemed to say: I see through all this, see to the bottom. She did not meet his glance. She was gazing thoughtfully at the coffee urn.

Her husband pushed back his plate. "Nancy least of all! Her mother is here, and old Jezebel. Her people have been in your family for four generations. You haven’t trained Nancy for Mrs. Grimwood. She stays here."

The icy quality, so effective with her servants, came into Mrs. Colbert’s voice as she answered him.

"It’s nothing to get flustered about, Henry. As you say, her mother and grandmother and great-grandmotherwere all Dodderidge niggers. So it seems to me I ought to be allowed to arrange Nancy’s future. Her mother would approve. She knows that a proper lady’s maid can never be trained out here in this rough country."

The miller’s frown darkened. "You can’t sell her without my name to the deed of sale, and I will never put it there. You never seemed to understand how, when we first moved up here, your troop of niggers was held against us. This isn’t a slave-owning neighbourhood. If you sold a good girl like Nancy off to Winchester, people hereabouts would hold it against you. They would say hard things."

Mrs. Colbert’s small mouth twisted. She gave her husband an arch, tolerant smile. "They have talked before, and we’ve survived. They surely talked when black Till bore a yellow child, after two of your brothers had been hanging round here so much. Some fixed it on Jacob, and some on Guy. Perhaps you have a kind of Family feeling about Nancy?"

"You know well enough, Sapphira, it was that painter from Baltimore."

"Perhaps. We got the portraits out of him, anyway, and maybe we got a smart yellow girl into the bargain." Mrs. Colbert laughed discreetly, as if the idea amused and rather pleased her. "Till was within her rights,seeing she had to live with old Jeff. I never hectored her about it."

The miller rose and walked toward the door.

"One moment, Henry." As he turned, she beckoned him back. "You don’t really mean you will not allow me to dispose of one of my own servants? You signed when Tom and Jake and Ginny and the others went back."

"Yes, because they were going back among their own kin, and to the country they were born in. But I’ll never sign for Nancy."

Mrs. Colbert’s pale-blue eyes followed her husband as he went out of the door. Her small mouth twisted mockingly. "Then we must find some other way," she said softly to herself.

Presently she rang for old Washington. When he came she said nothing, being lost in thought, but put her hands on the arms of the square, high-backed chair in which she sat. The old man ran to open two doors. Then he drew his mistress’s chair away from the table, picked up a cushion on which her feet had been resting, tucked it under his arm, and gravely wheeled the chair, which proved to be on castors, out of the dining-room, down the long hall, and into Mrs. Colbert’s bedchamber.

The Mistress had dropsy and was unable to walk. She could still stand erect to receive visitors: her dresses touched the floor and concealed the deformity of her feet and ankles. She was four years older than her husband— and hated it. This dropsical affliction was all the more cruel in that she had been a very active woman, and had managed the farm as zealously as her husband managed his mill.

II

At the hour when Sapphira Dodderidge Colbert was leaving the breakfast table in her wheel-chair, a short, stalwart woman in a sunbonnet, wearing a heavy shawl over her freshly ironed calico dress, was crossing the meadows by a little path which led from the highroad to the Mill House. She was a woman of thirty-six or -seven, though she looked older—looked so much like Henry Colbert that it was not hard to guess she was his daughter. The same set of the head, enduring yet determined, the broad, highly coloured face, the fleshy nose, anchored deeply at the nostrils. She had the miller’s grave dark eyes, too, set back under a broad forehead.

After crossing the stile at the Mill House, Mrs. Blake took the path leading back to the negro cabins. She must stop to see Aunt Jezebel, the oldest of the Colbert negroes, who had been failing for some time. Mrs. Blake was always called where there was illness. She had skill and experience in nursing; was certainly a better help to the sick than the country doctor, who had never been away to any medical school, but treated his patients from Buchan’s Family Medicine book.

On being told that Aunt Jezebel was asleep, Mrs. Blake passed the kitchen (separated from the dwelling by thirty feet or so), and entered the house by the back door which the servants used when they carried hot food from the kitchen to the dining-room in covered metal dishes. As she went down the long carpeted passage toward Mrs. Colbert’s bedchamber, she heard her mother’s voice in anger—anger with no heat, a cold, sneering contempt.

"Take it down this minute! You know how to do it right. Take it down, I told you! Hairpins do no good. Now you’ve hurt me, stubborn!"

Then came a smacking sound, three times: the wooden back of a hairbrush striking someone’s cheek or arm. Mrs. Blake’s firm mouth shut closer as she knocked. The same voice asked forbiddingly:

"Who is there?"

"It’s only Rachel."

As Mrs. Blake opened the door, her mother spoke coolly to a young girl crouching beside her chair: "You may go now. And see that you come back in a better humour."

The girl flitted by Mrs. Blake without a sound, her face averted and her shoulders drawn together.

Mrs. Colbert in her wheel-chair was sitting at a dressing-table before a gilt mirror, a white combing cloth about her shoulders. This she threw off as her daughter entered.

"Take a chair, Rachel. You’re early." She spoke politely, but she evidently meant "too early."

"Yes, I’m earlier than I calculated. I stopped to see old Jezebel, but she was asleep, so I came right on in."

Mrs. Colbert smiled. She was always amused when people behaved in character. Sooner than disturb a sick negro woman, Rachel had come in to disturb her at her dressing hour, when it was understood she did not welcome visits from anyone. How like Rachel!

For all Mrs. Blake could see, her mother’s grey-and-chestnut hair was in perfect order; combed up high from the neck and braided in a flat oval on the crown, with wavy wings coming down on either side of her forehead.

"You might get me a fresh cap out of the upper drawer, Rachel. I hate a frowsy head in the morning. Thank you. I can arrange it." She pinned the small frill of ribbon and starched muslin over the flat oval. "Now," she said affably, "you might turn me a little, so that I can see you."

Her chair was carved walnut, with a cane back and down-curved arms: one of the dining-room chairs, madeover for her use by Mr. Whitford, the country carpenter and coffin-maker. He had cushioned it, and set it on a walnut platform with iron castors underneath. Mrs. Blake turned it so that her mother sat in the sunlight and faced the east windows instead of the looking-glass.

"Well, I suppose it is a good thing Jezebel can sleep so much?"

Mrs. Blake shook her head. "Till can’t get her to eat anything. She’s weaker every day. She’ll not last long."

Mrs. Colbert smiled archly at her daughter’s solemn face. "She has managed to last a good while: something into ninety years. I shouldn’t care to last that long, should you?"

"No," Mrs. Blake admitted.

"Then I don’t think we need make long faces. She has been well taken care of in her old age and her last sickness. I mean to go out to see her; perhaps today. Rachel, I have a letter here from Sister Sarah I must read you." Mrs. Colbert took out her glasses from a reticule attached to the arm of her chair. She read the letter from Winchester chiefly to put an end to conversation. She knew her daughter must have heard her correcting Nancy, and therefore would be glum and disapproving. Never having owned any servants herself, Rachel didn’t at all know how to deal with them. Rachel had alwaysbeen difficult,—rebellious toward the fixed ways which satisfied other folk. Mrs. Colbert had been heartily glad to get her married and out of the house at seventeen.

While the letter was being read, Mrs. Blake sat regarding her mother and thought she looked very well for a woman who had been dropsical nearly five years. True, her malady had taken away her colour; she was always pale now, and, in the morning, something puffy under the eyes. But the eyes themselves were clear; a lively greenish blue, with no depth. Her face was pleasant, very attractive to people who were not irked by the slight shade of placid self-esteem. She bore her disablement with courage; seldom referred to it, sat in her crude invalid’s chair as if it were a seat of privilege. She could stand on her feet with a good air when visitors came, could walk to the private closet behind her bedroom on the arm of her maid. Her speech, like her handwriting, was more cultivated than was common in this back-country district. Her daughter sometimes felt a kind of false pleasantness in the voice. Yet, she reflected as she listened to the letter, it was scarcely false—it was the only kind of pleasantness her mother had,—not very warm.

As Mrs. Colbert finished reading, Mrs. Blake said heartily: "That is surely a good letter. Aunt Sarah always writes a good letter."

Mrs. Colbert took off her glasses, glancing at her daughter with a mischievous smile. "You are not put out because she makes fun of your Baptists a little?"

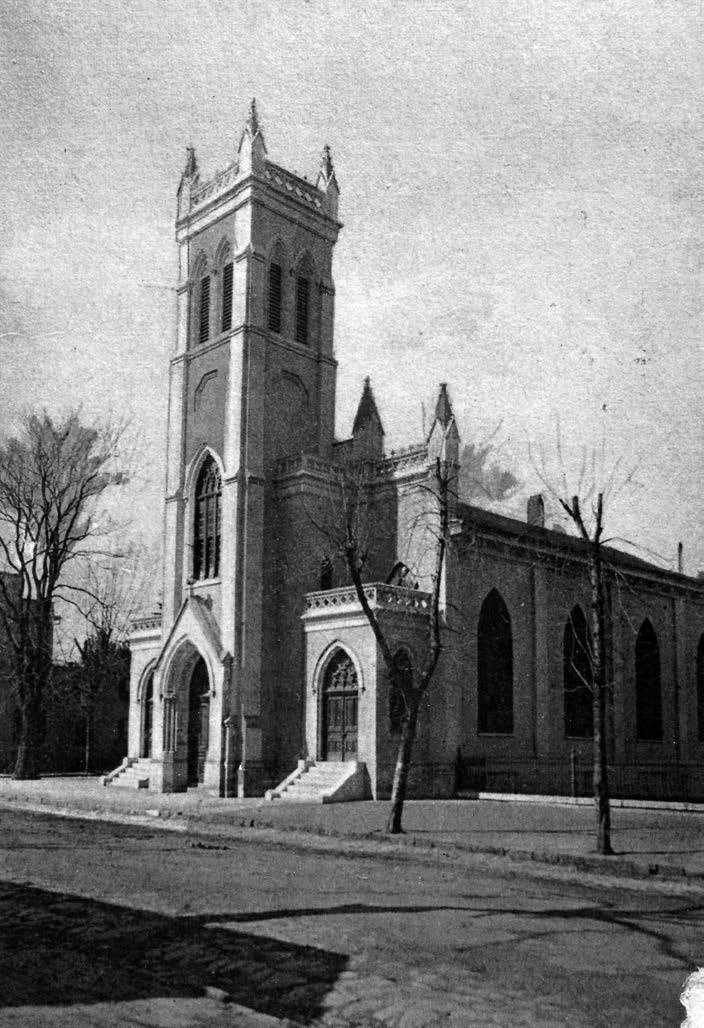

"No. She’s a right to. I’d never have joined with the Baptists if I could have got to Winchester to our own Church. But a body likes to have some place to worship. And the Baptists are good people."

"So your father thinks. But then he never did mind to forgather with common people. I suppose that goes with a miller’s business."

"Yes, the common folks hereabouts have got to have flour and meal, and there’s only one mill for them to come to." Mrs. Blake’s voice was rather tart. She wished it hadn’t been, when her mother said unexpectedly and quite graciously:

"Well, you’ve surely been a good friend to them, Rachel."

Mrs. Blake bade her mother good-bye and hurried down the passage. At times she had to speak out for the faith that was in her; faith in the Baptists not so much as a sect (she still read her English Prayer Book every day), but as well-meaning men and women.

Leaving the house by the back way, she saw the laundry door open, and Nancy inside at the ironing-board. She turned from her path and went into the laundry cabin.

"Well, Nancy, how are you getting on?" She habitually spoke to people of Nancy’s world with a resolute cheerfulness which she did not always feel.

The yellow girl flashed a delighted smile, showing all her white teeth. "Purty well, mam, purty well. Oh, do set down, Miz’ Blake." She pushed a chair with a broken back in front of her ironing-board. Her eyes brightened with eager affection, though the lids were still red from crying.

"Go on with your ironing, child. I won’t hinder you. Is that one of Mother’s caps?" pointing to a handful of damp lace which lay on the white sheet.

"Yes’m. This is one of her comp’ny ones. I likes to have ’em nice." She shook out the ball of crumpled lace, blew on it, and began to run a tiny iron about in the gathers. "This is a lil’ child’s iron. I coaxed it of Miss Sadie Garrett. She didn’t use it for nothin’, an’ it’s mighty handy fur the caps."

"Yes, I see it is. You’re a good ironer, Nancy."

"Thank you, mam."

Mrs. Blake sat watching Nancy’s slender, nimble hands, so flexible that one would say there were no hard bones in them at all: they seemed compressible, like a child’s. They were just a shade darker than her face. If her cheeks were pale gold, her hands were what Mrs.Blake called "old gold." She was considering Nancy’s case as she sat there (the red marks of the hairbrush were still on the girl’s right arm), wondering how much she grieved over the way things were going. Nancy had fallen out of favour with her mistress. Everyone knew it, and no one knew why. Self-respecting negroes never complained of harsh treatment. They made a joke of it, and laughed about it among themselves, as the rough mountain boys did about the lickings they got at school. Nancy had not been trained to humility. Until lately Mrs. Colbert had shown her marked favouritism; gave her pretty clothes to set off her pretty face, and liked to have her in attendance when she had guests or drove abroad.

"Well, child, I must be going," Mrs. Blake said presently. She left the laundry and walked about the negro quarters to look at the multitude of green jonquil spears thrusting up in the beds before the cabins. They would soon be in bloom. "Easter flowers" was her name for them, but the darkies called them "smoke pipes," because the yellow blossoms were attached to the green stalk at exactly the angle which the bowl of their clay pipes made with the stem.

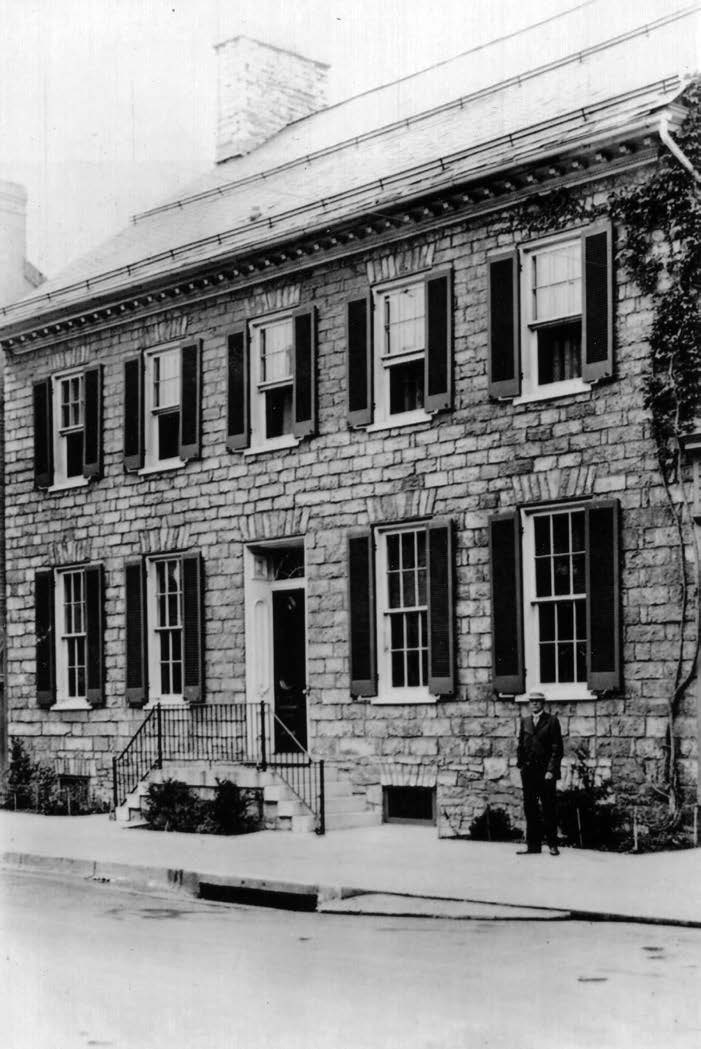

III

The Mill House was of a style well known to all Virginians, since it was built on very much the same pattern as Mount Vernon: two storeys, with a steep-pitched roof and dormer windows. It stood long and thin, and a front porch, supported by square frame posts, ran the length of the house. From this porch the broad green lawn sloped down a long way, to a white picket fence where the mill yard began. Its box-hedged walks were shaded by great sugar maples and old locust trees. All was orderly in front; flower-beds, shrubbery, and a lilac arbour trimmed in an arch beneath which a tall man could walk. Behind the house lay another world; a helter-skelter scattering, like a small village.

Some ten yards from the back door of the house was the kitchen, entirely separate from it, according to the manner of that time. The negro cabins were much farther away. The cabins, the laundry, and the big two storey smokehouse were all draped with flowering vines, now just coming into leaf-bud: Virginia creeper, trumpet vine, Dutchman’s pipe, morning-glories. Butthe south side of every cabin was planted with the useful gourd vine, which grew faster than any other creeper and bore flowers and fruit at the same time. In summer the big yellow blossoms kept unfolding every morning, even after the many little gourds had grown to such a size one wondered how the vines could bear their weight. The gourds were left on the vine until after the first frost, then gathered and put to dry. When they were hard, they were cut into dippers for drinking, and bowls for holding meal, butter, lard, gravy, or any tidbit that might be spirited away from the big kitchen to one of the cabins. Whatever was carried away in a gourd was not questioned. The gourd vessels were invisible to good manners.

From Easter on there would be plenty of flowers growing about the cabins, but no grass. The "back yard" was hard-beaten clay earth, yellow in the sun, orderly only on Sundays. Throughout the working week clotheslines were strung about, flapping with red calico dresses, men’s shirts and blue overalls. The ground underneath was littered with old brooms, spades and hoes, and the rag dolls and home-made toy wagons of the negro children. Except in a downpour of rain, the children were always playing there, in company with kittens, puppies, chickens, ducks that waddled up from the millpond,turkey gobblers which terrorized the little darkies and sometimes bit their naked black legs.

When Sapphira Dodderidge Colbert first moved out to Back Creek Valley with her score of slaves, she was not warmly received. In that out-of-the-way, thinly settled district between Winchester and Romney, not a single family had ever owned more than four or five negroes. This was due partly to poverty—the people were very poor. Much of the land was still wild forest, and lumber was so plentiful that it brought no price at all. The settlers who had come over from Pennsylvania did not believe in slavery, and they owned no negroes. Mrs. Colbert had gradually reduced her force of slaves, selling them back into Loudoun County, whither they were glad to return. Her husband had needed ready money to improve the old mill. Here there were no large, rich farms for the blacks to work, as there were in Loudoun County. Many field-hands were not needed.

Sapphira Dodderidge usually acted upon motives which she disclosed to no one. That was her nature. Her friends in her own county could never discover why she had married Henry Colbert. They spoke of her marriage as "a long step down." The Colberts were termed "immigrants,"—as were all settlers who did not comefrom the British Isles. Old Gabriel Colbert, the grandfather, came from somewhere in Flanders. Henry’s own father was a plain man, a miller, and he trained his eldest son to that occupation. The three younger sons were birds of a very different feather. They rode with a fast fox-hunting set. Being shrewd judges of horses, they were welcome in every man’s stable. They were even (with a shade of contempt and only occasionally) received in good houses;—not the best houses, to be sure. Henry was a plain, hard-working, little-speaking young man who stayed at home and helped his father. With his father he regularly attended a dissenting church supported by small farmers and artisans. He was certainly no match for Captain Dodderidge’s daughter.

True, when Sapphira’s two younger sisters were already married, she, at the age of twenty-four, was still single. She saved her face, people said, by making it clear that she was bound down by the care of her invalid father. Captain Dodderidge had been seriously hurt while out hunting; in taking a stone wall, his horse had fallen on him. He survived his injury for three years. After his death, when the property was divided, Sapphira announced her engagement to Henry Colbert, who had never gone to her father’s house except on matters of business. After the Captain was crippled andailing, he often sent for young Henry to advise him about selling his grain, to write his business letters, and to keep an eye on the nominal steward. He had great confidence in Henry’s judgment.

Sapphira was usually present at their business conferences, and took some part in their discussions about the management of the farm lands and stock. It was she who rode over the estate to see that the master’s orders were carried out. She went to the public sales on market days and bought in cattle and horses, of which she was a knowing judge. When the increase of the flocks or the stables was to be sold, she attended to it with Henry’s aid. When the increase of the slave cabins was larger than needed for field and house service, she sold off some of the younger negroes. Captain Dodderidge never sold the servants who had been with his family for a long while. After they were past work, they lived on in their old cabins, well provided for.

When Sapphira announced her engagement, the family friends were more astonished than if she had declared her intention of marrying the gardener. They quizzed the negro servants, who declared that Mr. Henry had never been so much as asked into the parlour. They had never "caught" him talking to Miss Sapphy outside her father’s room, much less courting her.After all these years the strangeness of this marriage still came up in conversation when old friends got together. Fat Lizzie, the cook, had whispered to the neighbours on Back Creek: "Folks back home says it seem like Missy an’ Mr. Henry wasn’t scarcely acquainted befo’ de weddin’, nor very close acquainted evah since. Him bein’ kep’ so close at de mill," she would add suavely.

Since she did marry Henry, it was not hard to explain why Sapphira had moved away from her native county, where his plain manners, his calling, vague ancestry, even his Lutheran connections, would have made her social position rather awkward. Once removed several days’ journey from her old friends, she could go back to visit them without embarrassment. The miller’s unbending, somewhat uncouth figure need never appear upon the scene at all.

The bride chose Back Creek for her place of exile because she owned a very considerable property there, willed to her by an uncle who died when she was still a young girl. On this Back Creek estate there was a mill. It had stood there for some generations, since Revolutionary times.

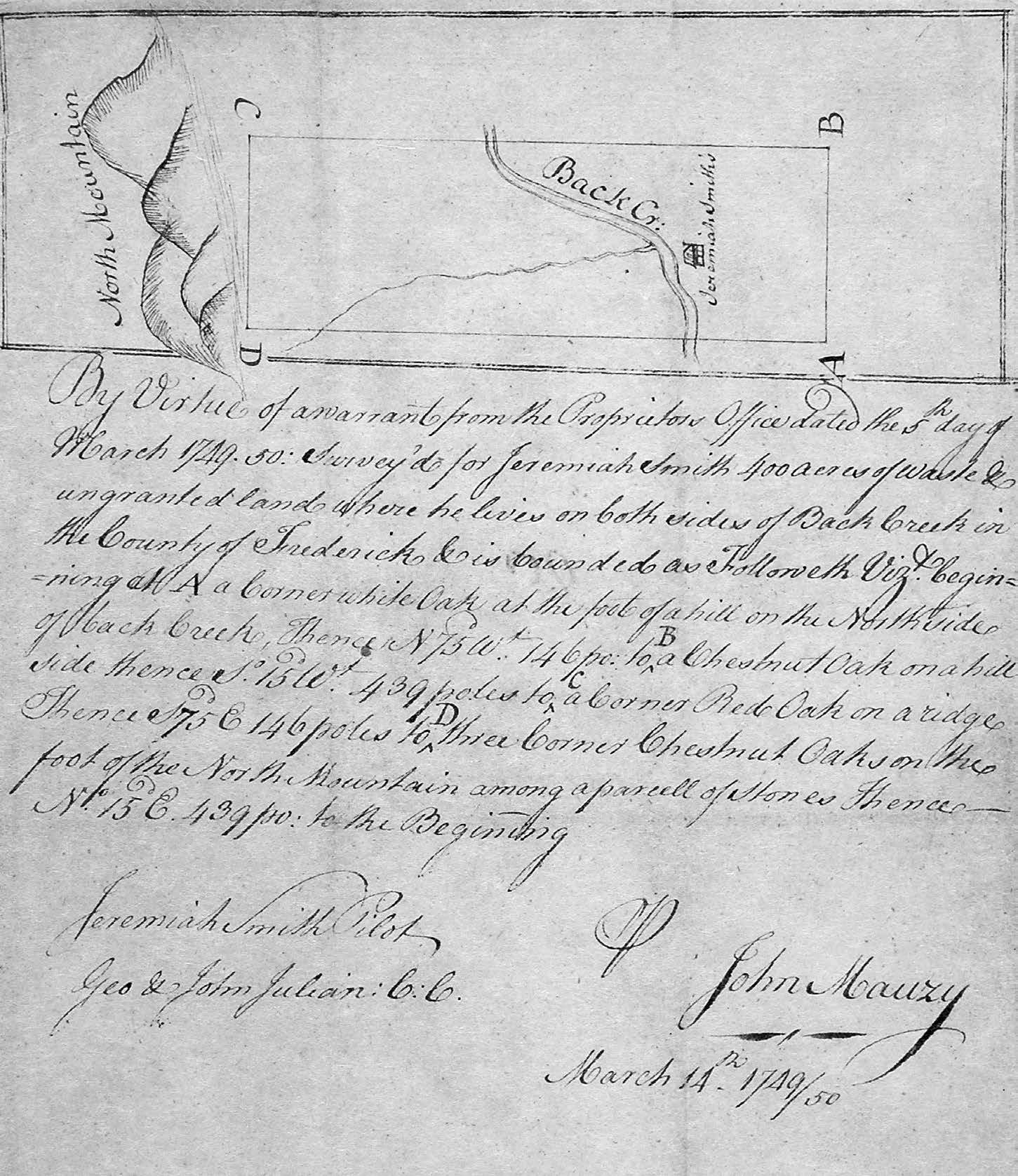

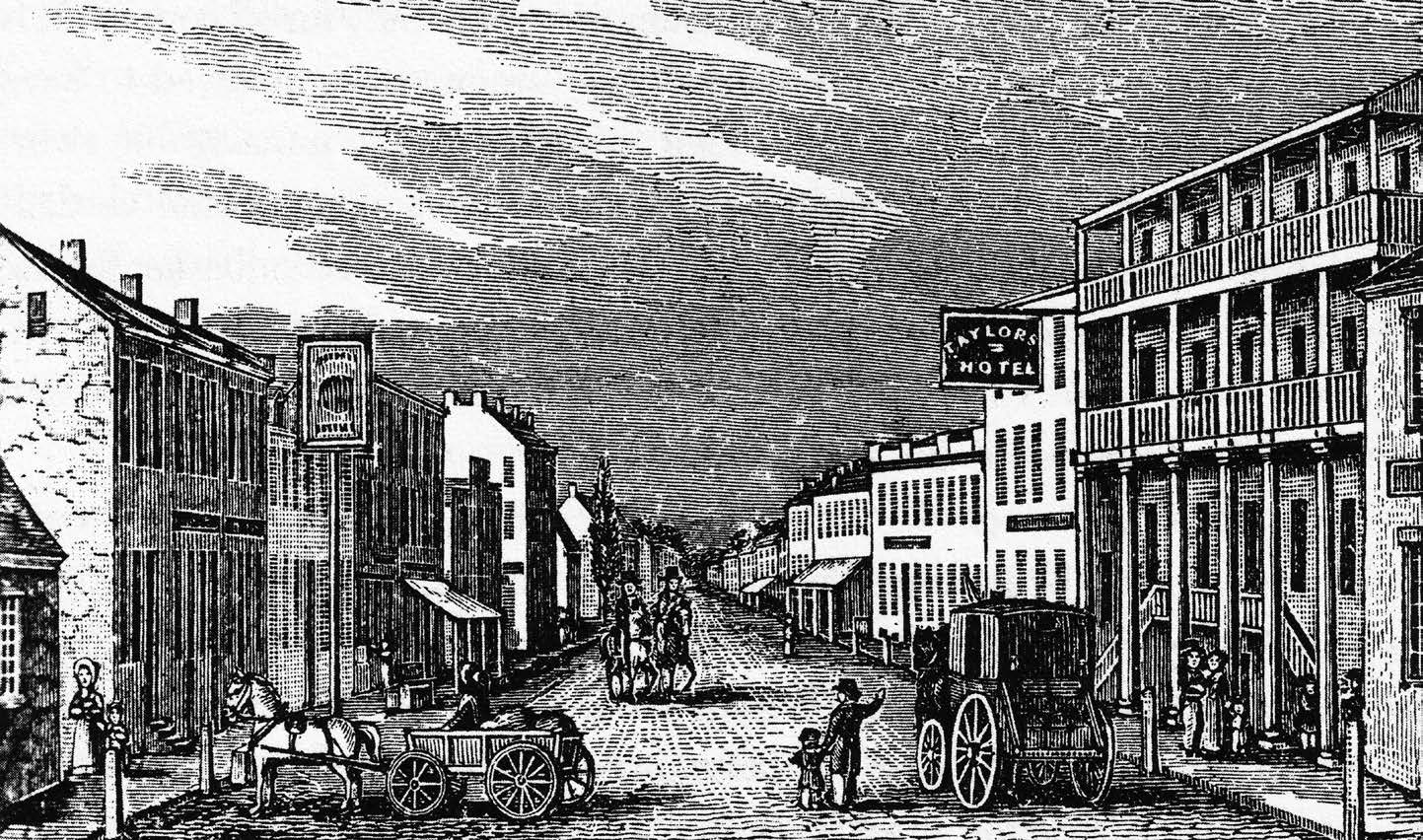

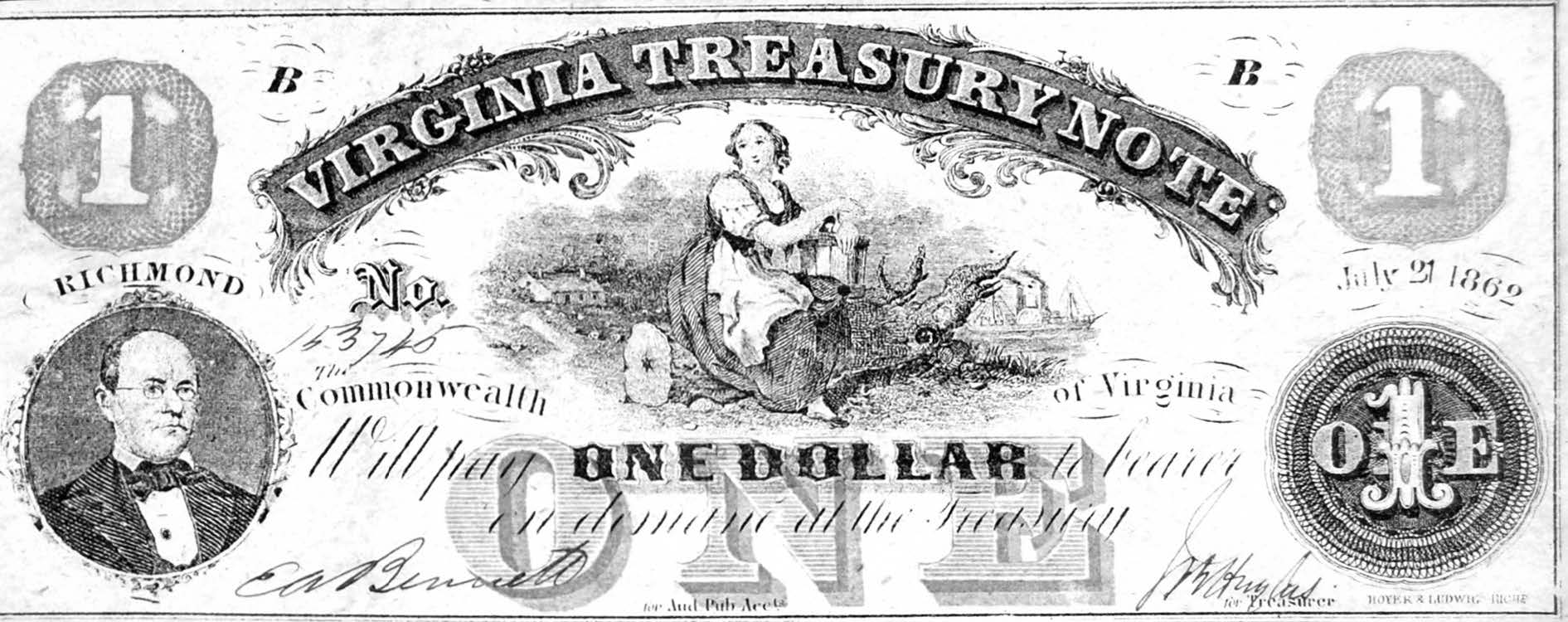

This farm (and a great tract of forest land afterward sold off ) had been deeded by Thomas, Lord Fairfax, to a Nathaniel Dodderidge who came out to Virginia withFairfax in 1747. Fairfax’s actual possessions in the colony were immense; something like five million acres of forest and mountain which had never been surveyed, watered by rivers, great and small, which had never been explored except by the Indians and were nameless except for their unpronounceable Indian names. There was discontent in the Virginia Assembly that so large a territory should be held in one grant. When Fairfax established his final residence in the Shenandoah Valley, he quieted this dissatisfaction by deeding off portions of his estate to desirable settlers, laying out towns, and in every way encouraging immigration.

To Nathaniel Dodderidge he deeded a tract of land on Back Creek. Neither Nathaniel nor any of his descendants had ever lived on this land. It was only after the capture of Quebec by young General Wolfe in 1759 that the mountainous country between Winchester and Romney was altogether safe for settlers. Bands of Indians under French captains had burned and slaughtered as near Back Creek as the Capon River.

When the danger of Indian raids was over, someone (his name was lost) built a water mill where Henry Colbert’s mill now stood. All through the Revolutionary War and ever since, a mill on that site had served the needs of the scattered settlers. The Dodderidges had letthe Mill Farm to tenants for successive generations. Sapphira’s father had never seen the place. But before his death Sapphira herself, attended by a groom, rode up a four days’ journey on horseback to look over her inheritance. One morning she arrived at the Back Creek post office, where a spare room was kept for travellers. Sapphira unpacked her saddle-bags and settled herself for a stay of several days. She rode all over the Mill Farm and the timber land; had a friendly interview with the resident miller and told him she could not renew his lease, which had barely a year to run.

Before Sapphira’s marriage to Henry Colbert, carpenters were sent out from Winchester to pull down the old mill house (it was scarcely more than a cabin), and to build the comfortable dwelling which now stood there. When the new house was completed, Sapphira’s household goods were carted up from Chestnut Hill and settled in it. She and Henry Colbert were married at Christ Church, in Winchester, and drove directly to the new Mill House on Back Creek, omitting the elaborate festivities which customarily followed a wedding.

Though it was often said that Miss Dodderidge had broken away from her rightful station, she by no means dropped out of the lives of her family or lost touch withher friends. Until her illness came upon her, she made every year a long visit to the sister who lived at Chestnut Hill, the old estate in Loudoun County. Even now she was always driven to Winchester in March, to stay with her sister Sarah until after Easter. There she attended all the services at Christ Church, where Lord Fairfax, the first patron of the Virginia Dodderidges, was buried beneath the chancel. With the help of her brother-in-law and a cane she limped to the family pew, though she was obliged to remain seated throughout the service.

She was a comely figure in the congregation, clad in black silk and white fichu. From lack of exercise she had grown somewhat stout, but she wore stays of the severest make and carried her shoulders high. Her serene face and lively, shallow blue eyes smiled at old friends from under a black velvet bonnet, renewed or "freshened" yearly by the town milliner. She had not at all the air of a countrywoman come to town. No Dodderidge who ever sat in that pew showed her blood to better advantage. The miller, of course, did not accompany her. Although he had been married in Christ Church, by an English rector, he had no love for the Church of England.

IV

Mrs. Colbert, in her morning jacket and cap, sat before her desk, writing a letter. She wrote with pauses for deliberation, which was unusual. She was not unhandy with the pen. When writing to her sisters she filled pages with small, neat script, having trained herself to "write small." Postage was accounted dear, and when she sent long letters to relatives in England it was an economy to put a great deal upon a sheet. This morning she was composing a letter to a nephew—a letter of invitation. It was meant to be cordial, but not too cordial. When she felt satisfied with it, she folded the sheet and sealed it with a dab of red wax. Envelopes were little in use. She rang the loud-voiced copper bell, always kept in the side pocket of her chair.

Old Washington appeared. "Yes, Missy?"

"I am minded to drive out, Washington. I have ordered the carriage, and Uncle Jeff must have it at the door presently. Find Till and tell her to come and get me ready."

"Yes, mam."

Mrs. Colbert turned her letter face-down upon her desk. Till could read, and the Mistress did not wish her to see to whom the letter was addressed. When the neat black woman came to the door Mrs. Colbert said cheerfully:

"Now, Till, you must dress me to drive abroad."

"Yes, Missy. The black cashmere, I reckon? It’s a wonderful nice day outside, Miss Sapphy. It’ll do you good."

Till, Nancy’s mother, was a black woman of about forty, straight and spare. Her carriage and deportment and speech were those of a well-trained housekeeper. She knew how to stand when receiving orders, how to meet visitors at the front door, how to make them comfortable in the parlour and see to their wants. She had been trained as parlour maid by the English housekeeper whom Sapphira’s mother had brought with her from Devon when she came out to Virginia to marry her American cousin. The housekeeper had seen in Till a "likely" girl who could be taught. Since Mrs. Colbert had lost the use of her feet, Till had charge of everything in the house except the kitchen and fat Lizzie, the cook, whom no one but Mrs. Colbert could control.

Till set about dressing her mistress; took off the morning jacket and slipped a starched white petticoatand a cashmere dress over Mrs. Colbert’s head. "Don’t raise yourself up, Miss Sapphy. I’ll pull everything down when you has to rise."

"Now the feet, I suppose," said Mrs. Colbert with a shrug. She seldom permitted herself to sigh. "Not the silk stockings. I shan’t be getting out anywhere. But you can put on the new kid-leather shoes. They hurt me, but I must be getting used to them."

"Now just you wear the cloth slippers and be easy, Miss Sapphy. Let me wear the kid shoes round the house a few days more an’ break ’em in for you."

"Hush, Till. You mustn’t baby me," her mistress joked, looking wishfully at the cloth slippers which Till was flapping on her two hands like mittens. "Well, put them on me, but this is the last time. You can’t do much at breaking in the new pair, for you have small feet. Almost as small as mine used to be." She regarded her feet and ankles with droll contempt while Till drew on the stockings and tied a ribbon garter below each of her wax-white, swollen knees.

"There’s Jeff now," Till exclaimed, as she tied the strings of her mistress’s second-best bonnet. She helped her to rise for a moment and pulled down the full skirts. Washington came at call and pushed Mrs. Colbert’s chair through the long hall to the front door. Outsidestood the coach, freshly washed; it looked very much like the "four-wheeler" public cab of later days. On the box sat a shrivelled-up old negro in a black coat much too big for him, and all that was left of a coachman’s hat. A little black boy came running up to hold the horses, while Jeff descended to help his mistress.

Leaning between Jeff and Washington, Mrs. Colbert crossed the porch and stepped down into the carriage. She settled herself on the leather cushions, and Jefferson was about to close the door when she said quite carelessly:

"Jefferson, what have you got on your feet?"

Jeff crouched. He had nothing at all on his feet. They were as bare as on the day he was born. "Ah thought nobody’d see mah fe-e-t on de box, Missy."

"You did? Take me out driving like some mountain trash, would you? Now you get out of my sight and put on that pair of Mr. Henry’s boots I gave you. Step!"

Jefferson scuttled off like an old rat. Washington went to help the boy hold the impatient horses. Till was leaning in at the carriage door, putting a cushion under her mistress’s slippers and a rug over her knees.

"Till," said Mrs. Colbert confidentially, "I wish you would tell me why it’s so hard to keep leather on a nigger’s feet."

"I jest don’t know, Miss Sapphy. The last thing I done was to caution that nigger about his boots. When I seen him wrigglin’ his old crooked toes yonder in the gravel, I was that shamed!" Till spoke indignantly. She was ashamed. Jeff was her husband, had been these many years, though it was by no will of hers.

Jeff came back, his pants stuffed into a pair of old boots which needed blacking, and hurriedly climbed on to the box.

"Jeff, you drive careful, now!" Till called. Washington and the black boy stepped back from the horses, and the coach rolled down the driveway. The drive led past the mill, and Sampson, the head mill-hand, came out to wave and call: "Pleasant drive to you, Miss Sapphy!"

To the household it was an occasion when the Mistress drove out. In this backwoods country there were few families Mrs. Colbert cared to call upon, and she had no special liking for rough mountain roads. When the wild laurel was in bloom, or the wild honeysuckle (Rhododendron nudiflorum), then she often drove up the winding road to Timber Ridge. She knew she looked to advantage when she stopped to pass the time of day with her neighbours through the lowered window of her coach. Very few people, even in Loudoun County,

had glass windows in their carriages. Moreover, on the coach door there was a small patch of colour, the Dodderidge crest: her "coat of arms," the Back Creek people called it. The children along the road used to stare wonderingly at that mysterious stamp of superiority.

This morning when Jefferson came to the place where the mill road turned into the highroad, he asked in his cracked treble:

"Which-a-way, Missy?"

She told him to the post office, so he turned west. When he had gone a mile, he slowed his horses to a walk. There was Mrs. Blake’s house, standing under four great maple trees, in a neat yard with a white paling fence. Two little girls ran out, calling: "Good morning, Gran’ma!"

Jefferson stopped the carriage, and Mrs. Colbert asked after their mother.

"Ma ain’t at home," said the older child. "She’s gone over to Peughtown. Mrs. Thatcher’s dreadful sick. They came for Ma in the night, and brought a horse for her."

"So you are all by yourselves? Suppose you get in and take a ride to the post office?"

The children shot quick glances at each other. The younger one, who was only eight, said timidly: "We’ve got just our old dresses on, Gran’ma."

Her grandmother laughed. "Oh, never mind, this time! Jump in, the horses don’t like to stand. Molly’s curls are nice, anyhow."

The children climbed into the carriage, delighted at their good luck. Sometimes, when their grandmother was driving of a Sunday morning, she stopped and took them and their mother as far as the Baptist church; but very seldom had they driven out with her by themselves. This was Saturday, and Molly wished that all her schoolmates could be loitering along the road to see them go by. Her real name was Mary, but since she promised to be a pretty girl, her grandmother had taken a fancy to her and called her Molly. It was understood that this name was Mrs. Colbert’s special privilege; her mother and her schoolmates called her Mary. Her little sister was the only one who dared to use Grandmother’s name for her.

Uncle Jeff drew his horses up before the long, low, white-painted house where the postmistress lived and performed her official duties. The postmistress herself threw an apron over her head and came out to the carriage. She and Mrs. Colbert greeted each other with marked civility. They held very different opinions on one important subject.

Mrs. Colbert drew from her reticule the letter she had written a few hours ago. "I brought this letter up to you myself, Mrs. Bywaters, because it is important, and I hope you will put it into the mailbag yourself."

"Certainly, Mrs. Colbert. Nobody but me ever handles the mail here. The bag goes from my hands into the stage-driver’s. I see you’ve got your little granddaughters along today."

"Yes, Mrs. Bywaters, this is a pleasant day for a drive. I’d heard you had your house new painted. How nice it looks!"

"Thank you. I had trouble enough getting it done, but it’s over at last. I had to tear down all my honeysuckle vines and lay them on the ground. I’m hoping they’re not much hurt."

"I hope not, indeed. They were a great ornament to your house, especially the coral honeysuckle. Now, Jefferson, we will stop at the store for a minute. Good day to you, Mrs. Bywaters."

The country store stood across the road from the post office. The storekeeper saw the carriage stop, and came out. Mrs. Colbert asked him to bring her a pound of stick candy, half wintergreen and half peppermint. Both little girls tried to look unconscious, but while their grandmother was talking to the storekeeper, Bettypinched Mary softly to express her feelings. The candy was brought out in a brown paper parcel, but it was not given to them until their grandmother let them out at their own gate. They thanked her very prettily for the candy and the drive.

"Jefferson, you may take me down the turnpike, and out to Mrs. Cowper’s on the Peughtown road. I want to ask after my carpets."

As she drove along, Mrs. Colbert was thinking it was fortunate that for once her daughter had been called to nurse in a prosperous family like the Thatchers, who would see that she was well repaid; if not in money, in hams or bacon or a bolt of good cloth. Usually she was called out to some bare mountain cabin where she got nothing but thanks, and likely as not had to take along milk and eggs and her own sheets for the poor creature who was sick. Rachel was poor, and it was not much use to give her things. Whatever she had she took where it was needed most; and Mrs. Colbert certainly didn’t intend to keep the whole mountain.

After a few miles of jolting over a rough by-road, she stopped for a call on Mrs. Cowper, the carpet-weaver. At the Mill House all worn-out garments, discarded table linen, and old sheets were cut into narrow strips, sewn together, and wound into fat balls. This was the darkies’ regular evening work in winter. When a great many balls of these "carpet-rags" had accumulated, they were sent, with hanks of cotton chain, to Mrs. Cowper, who dyed them with logwood, copperas, or cochineal, then wove them into stout carpets, striped or plain.

V

As soon as the Mistress had left the house, Till and her daughter Nancy fell to and began to give her bedroom a thorough cleaning; pushed the bed out from the wall, and washed the closet floors. All the windows were opened, and the rugs before the wash-basin stand and the dressing-table were carried into the back yard and beaten.

After Nancy had pinned a clean antimacassar on the back of the wheel-chair and put the Mistress’s slippers ready at the foot of it, her mother said they might as well "give the parlour a lick" before the carriage got back.

The two women, their heads tied up in red cotton handkerchiefs, went into the parlour and rolled up the green paper shades, painted with garden scenes and fountains. The sunlight streamed into the room. The parlour was long in shape, not square, with a low ceiling, the brick fireplace in the middle, under a wide mantel shelf. Horsehair chairs and sofas sat about with tidies on their backs and arms. Captain Dodderidge’s old mahogany desk filled one corner. Every inch of the floorwas covered by a heavy Wilton carpet, figured with pink roses and green leaves. It was somewhat worn, as it had been "brought over" by Sapphira’s mother when she first came out to Virginia. Upon this carpet the two brooms went swiftly to work.

The room had an air of settled comfort and stability; visitors sensed that at once. The deep-set windows made one feel the thickness of the walls. A child could climb up into one of those windows and make a playhouse. Every afternoon Mrs. Colbert was brought into the parlour and sat here for several hours before supper. Here she could watch the light of the sinking sun burn on the great cedars that grew along the farther side of the creek, across from the mill. In winter weather, when the snow was falling over the flower garden and the hedges, that long room, with its six windows and its warm hearth, was a pleasant place to be.

With Nancy at one end and Till at the other, the parlour was soon swept. Till never dawdled over her work. The housekeeper at Chestnut Hill had taught her that the shuffling foot was the mark of an inferior race. After the sweeping came the dusting.

"Now, Nancy, run and fetch me a kitchen chair and a clean soft rag. I want to git at the po’traits, which I didn’t have time to do last week." Any other servant onthe place would have stepped coolly on one of the fat horsehair chair-bottoms,—if, indeed, she had thought it worth while to dust the pictures at all, now that the Mistress could no longer reach up and run her fingers along the frames.

When the wooden chair was brought, Till mounted and wiped, first the canvases, then their heavy gilt frames. Her daughter stood gazing up at them: Master and Mistress twenty years ago. Mistress in a garnet velvet gown and real lace, wearing her long earrings and a garnet necklace: a vigorous young woman with chestnut hair and a high colour in her cheeks. The Master in a stock and broadcloth coat, his bushy black hair standing up as it often did now, his face broad and ruddy; he had changed very little. Nancy thought these pictures wonderful. She hoped the painter was really her father, as some folks said. Old Jezebel, her great-grandmother, had whispered to her that was why she had straight black hair with no kink in it.

Anyway, Nancy knew Uncle Jeff wasn’t her father, though she always called him "Pappy" and treated him with respect. Her mother had no children by Uncle Jeff, and fat Lizzie, the cook, had left Nancy in no doubt as to the reason. When Nancy was a little girl, Lizzie had coaxed her off into the bushes one Sunday to help herpick gooseberries. There she told her how Miss Sapphy had married Till off to Jeff because he was a "capon man." The child was puzzled, and thought this meant that Jeff had come from somewhere up on the Capon River. But Lizzie made the facts quite clear. Miss Sapphy didn’t want a lady’s maid to be "havin’ chillun all over de place,—always a-carryin’ or a-nussin’ ’em." So she married Till off to Jeff and "made it wuth her while, the niggers reckoned." Till got the light end of the work and the best of everything. And Lizzie didn’t believe that talk about the painter man; she told Nancy that one of Mr. Henry’s brothers was her real father. From that day Nancy had felt a horror of Lizzie. She tried not to show it, but Lizzie knew, and she got back at the stuck-up piece whenever she had a chance. She set her own daughter, Bluebell, to spy on Till’s girl.

Nancy had never asked Till who her father was. She admired her mother and took pride in what she called her mother’s "nice ways." The girl had a natural delicacy of feeling. Ugly sights and ugly words sickened her. She had Till’s good manners—with something warmer and more alive. But she was not courageous. When the servants were gossiping at their midday dinner in the big kitchen, if she sensed a dirty joke coming, she slipped away from the table and ran off into thegarden. If she felt a reprimand coming, she sometimes lied: lied before she had time to think, or to tell herself that she would be found out in the end. She caught at any pretext to keep off blame or punishment for an hour, a minute. She didn’t tell falsehoods deliberately, to get something she wanted; it was always to escape from something.

Nancy was startled out of her reflections about her mysterious father by her mother’s voice.

"Now, honey, if I was you, I’d make a nice egg-nog when you hear the carriage comin’, an’ I’d carry it in to the Mistress when she’s got out of the coach an’ into her room. I’d take it to her on the small silvah salvah, with a white napkin and some cold biscuit."

Nancy caught her breath, and looked downcast. "Lizzie, she don’t like to have me meddlin’ round the kitchen to do anything."

"I’ll be out around the kitchen, an’ Lizzie dassent say anything to me. An’ if I was you, I wouldn’t carry a tray to Missus with no haing-dawg look. I’d smile, an’ look happy to serve her, an’ she’ll smile back."

Nancy shook her head. Her slender hands dropped limp at her side. "No she won’t, Mudder," very low.

"Yes she will, if you smile right, an’ don’t go shiverin’ like a drownded kitten. In all Loudoun County MissSapphy was knowed for her good mannahs, an’ that she knowed how to treat all folks in their degree."

The daughter hesitated, but did not answer. For nearly a year now she had seemed to have no degree, and her mistress had treated her like an untrustworthy stranger. Before that, ever since she could remember, Miss Sapphy had been very kind to her, had liked her and had shown it. As they were leaving the parlour, Nancy murmured, more to herself than to her mother:

"I knows that fat Lizzie’s at the bottom of it, somehow. She’s always got a pick on me."

VI

The mill stood on the west bank of Back Creek: the big water-wheel hung almost over the stream itself. The creek ran noisily along over a rough stone bottom which here and there churned the dark water into foam. For the most part it was wide and shallow, though there were deep holes between the ledges. The dam, lying in the green meadows above the mill, was fed by springs, and a race conveyed the water to the big wooden wheel.

In the second storey of the mill flour and unground grain were stored; there it was safe in times of high water. The "miller’s room," on the first floor, was a recognized feature of every mill in those days; the man in charge slept there and kept an eye on the property, even when no grinding was going on at night. Henry Colbert had no foreman. He himself occupied the room, using it both as sleeping-chamber and office. Years ago he spent the night at the mill only in times of night grinding or high water. But latterly the mill room had become more and more the place where he actually lived.

The mill room was all that was left of the original building which stood there in Revolutionary times. The old chimney was still sound, and the miller used the slate-paved fireplace in cold weather. The floor was bare; old boards, very wide, ax-hewn from great trees before the day of sawmills. There was no ceiling but the floor of the storeroom above, with its heavy, ax-dressed cross-beams. This wooden ceiling, its beams, and the wooden walls of the room were freshly whitewashed every spring. The miller’s furniture was whitewashed, so to speak, day by day, by the flour-dust which sifted down from overhead, and through every crack and crevice in the doors and walls. Each morning Till’s Nancy swept and dusted the flour away.

Here the miller had arranged everything to his own liking. The square windows were furnished with paper blinds, to keep out the four-o’clock summer dawn if he had been up late the night before. His narrow bed had been made of chestnut wood by Mr. Whitford, the neighbourhood carpenter and cabinet-maker, and it was a good piece of work. Bed-cords, hitched about neat knobs, took the place of springs. On the tightly drawn cords lay the mattress; a feather "tick" in winter, a corn-shuck one in summer. His "secretary" was also of chestnut. (Whitford liked to work in that wood.) Itwas both writing-desk and bookcase. Above the desk four shelves held ledgers and account books,—and a curious assortment of other books as well. The high chest of drawers at which the miller shaved stood between the two west windows, looking toward the house, and his small wood-framed looking-glass hung from a nail driven in the plank wall behind. At seven o’clock every morning little Zach ran down from the house with the master’s shaving water in a steaming iron teakettle.

When Henry Colbert first took over the mill, his silent unconvivial nature was against him. A miller was expected to be jovial; to produce whisky, or at least applejack, when a man made a small payment on a long account. In time his neighbours found that though the new miller was stingy of speech, he was not tight with his purse-strings.

One rainy March day at about four o’clock in the afternoon (in Virginia one said four o’clock in the "evening") the miller was sitting at his secretary, going through his ledger. His purpose was to check off the names of debtors to whom he would not, under any circumstance, extend further credit. He found so many of these names already checked once, and even twice, that after frowning over his accounts for a long while,he leaned back in his chair and rubbed his chin. When people were so poor, what was a Christian man to do? They were poor because they were lazy and shiftless,— or, at best, bad managers. Well, he couldn’t make folks over, he guessed. And they had to eat. While he sat thinking, Sampson, his head mill-hand, appeared at the door, which was often left ajar in the daytime.

"Mr. Henry, little Zach jist run down from de house sayin’ de Mistress would like you to come up, if you ain’t too busy."

The miller closed his ledger, glad to escape. "Anything amiss, Sampson?"

"No, sah, I don’t reckon so. Zach, he said she was waitin’ in de parlour."

Colbert changed his old leather jacket for a black coat, brushed the flour-dust off his broad hat, and walked up through the cold spring drizzle which was making the grass green.

He found his wife dressed for the afternoon, with a lace cap on her head and her rings on her fingers, having her tea by the fire. (When she heard him open the front door she poured his cup, smuggling in a good tot of Jamaica rum, since he didn’t take cream.) Before he sat down, he took up a plate of toasted biscuit from the hearth and offered it to his wife. He drank his tea in a few swallows, though it was very hot.

"Thank you, Sapphy. That takes the chill out of a body’s bones. It does get damp down there at the mill. Could you spare me another cup?"

Munching his biscuit, he watched her pour the tea. When she reached down for a small red cruet, well concealed on the lower deck of the table, he laughed and rubbed his hands together. "That’s why it tastes so good! I must try to get up here oftener when you’re having your tea. But it’s just about this time of day the farmers come in. The good ones are at work all morning, and the poor sticks never get around to anything at all till the day’s ’most gone."

"I’m sure the Master would always be very welcome company in the evenings," replied Mrs. Colbert, lifting her eyebrows, whether archly or ironically it would be hard to say.

"Don’t you put on with me, Sapphy." He reached down to the hearth for another biscuit. "You’re the master here, and I’m the miller. And that’s how I like it to be."

His wife looked at him with an indulgent smile, and shook her head. She stirred her tea gently for a few moments in silence. A log fell apart in the fire and shot up tall flames; the miller put the ends together with the tongs. "Henry," she said suddenly, "do you realize it’s getting on towards Easter?"

"And you haven’t set out yet," he added. "Have you given up going for this year?"

"No, I wouldn’t disappoint Sister Sarah. But Jezebel’s been so low. I shouldn’t like to be away from home when it happened. I thought she would have gone before this."

Colbert glanced up in surprise. "Well, you needn’t put yourself out on Jezebel’s account. She may hang on till harvest. It seems like life won’t let go of her."

"If you feel that way, what’s to hinder my going this Friday? Then I would have all Holy Week with Sarah, and if I get no bad news from home I might stay a week longer. Sarah always entertains after Easter, you know, and I would meet my old friends."

"I can see no objection. The roads ought to be good, if this drizzle don’t set into a hard rain. While you’re in town you might have the carriage painted. It needs it."

"That’s a good idea. And this year I think I shall take Nancy along instead of Till. It would smarten her up, to see how people do things in town."

He considered a moment. "Very well, if you leave Till to look after my place down there. Don’t try any more Bluebell on me!"

His wife replied with her most ladylike laugh, a flash of fun in it. "Poor Bluebell! Is she never to have a chance to learn? Why are you so set against her?"

"I can’t abide her, or anything about her. If there is one nigger on the place I could thrash with my own hands, it’s that Bluebell!"

The Mistress threw up her hands; this time she laughed so heartily that the rings on her fingers glittered. It was a treat to hear her husband break out like this.

"Well, Henry," as she wiped her eyes with a tiny handkerchief, "I will own to you that if it wasn’t for Lizzie’s feelings, I’d send that lazy girl off the place tomorrow. I’d give her away! But we’ve got the only good cook west of Winchester, and so we have to have Bluebell. Lizzie would always be in the sulks, and when a cook is out of temper she can spoil every dish, just by a turn of the hand. We would never sit down to a good dinner again. Besides, your Baptists would miss Lizzie and Bluebell in the hymns. And they are always being sent for to sing at funerals. I like to hear them myself, of a summer night."

The miller rose, put another log on the fire, and, by way of an attention, righted the clumsy wheel-chair a little. He took his wife’s plump hand and patted it. "Thank you for having me up, Sapphy. It’s done me good. The mill room gets very damp between seasons, and I forget to have Tap make a fire. You might send forme a little oftener." He turned up his coat-collar and reached for his hat, but his wife interfered.

"Go and get your shawl out of the hall press. Don’t go back to the mill and sit in a damp coat. It’s folly to expose yourself. You ought to have a fire every day this weather."

He went into the hall and returned with a great shawl of fine Scotch wool. It had once been dark green, but time and weather had put a dull gold cast into it. He folded it three-cornered, so that it covered his coat, and went out into the drizzle. Military men and prosperous townsmen wore overcoats, but farmers and countrymen wore heavy shawls, fastened with a large shawl-pin.

Sapphira sat looking out at the dripping trees and the thick amethyst clouds which hung low over the mill and blurred the tall cedars across the creek. She smiled faintly; it occurred to her that when they were talking about Bluebell, both she and Henry had been thinking all the while about Nancy. How much, she wondered, did each wish to conceal from the other?

Such speculations were mildly amusing for a woman who did not read a great deal, and who had to sit in a chair all day.

She had given little time to reflection in the years when she was having her children and bringing them up. Even after they were married and gone, the management of the place had kept her busy. Every year there was the gardening and planting, butchering time and meat-curing. Summer meant preserving and jelly-making, the drying of cherries and currants and sweet corn and sliced apples for winter. In those days she often rode her mare to Winchester of a Saturday to be there for the Sunday service. It was because she had been so energetic, and such a good manager, that even from an invalid’s chair she was still able to keep her servants well in hand.

BOOK TWO

Nancy and Till

BOOK II

I

On Thursday morning two leather coach trunks were brought down from the garret, and Nancy was allowed, for the first time, to pack them, under Till’s direction. Besides the trunks, there was a handy Whitford-made wooden box for shoes, as the poor Mistress had to carry so many pairs. The bandboxes were to go inside the carriage.

By eleven o’clock on Friday morning Mrs. Colbert was dressed and bonneted. All the household gathered round the carriage to see her off. Fat Lizzie brought the lunch-box, for light refreshment on the road to Winchester. The miller came up from the mill to lift his wife into the carriage. Nancy, in her Sunday bonnet and shawl, stood by, expecting to sit on the box with Uncle Jeff, but Mrs. Colbert told her she was to ride inside. The servants called good wishes as Jeff drove off, and Henry walked beside the coach as far as the mill. Nancy had cast an appealing glance at her mother when she learned she was to sit beside the Mistress. But Till knew the Dodderidge manners; if the girl was taken as a companion, she would be treated as such.

After Till had closed the Mistress’s room, she went down to the mill to "straighten up" for Mr. Henry. She had her own sense of the appropriate, and she thought the miller’s room right for him, in the same way that Captain Dodderidge’s saddle room had always been right. She approved of the polished chestnut bedstead, and the counterpane in large blue and white squares, woven by the same Mrs. Cowper who made carpets. The four brass candlesticks, by which the miller read after dark, were clean and shining; only a little tallow from last night had dripped down the stems. The deep chair beside the reading-table was made of bent hickory withes, very strong and well fitted to the back. Till had wanted to make cushions for this chair, but the Master told her cushions were for women. She was glad to see that Nancy had kept Mr. Henry’s copper pieces bright: she knew he set great store by these.

Between the whitewashed uprights that held the board walls together, the miller had fitted wooden shelves. On these he kept sharp and delicate tools, which the mill-hands were on no account allowed to touch, and a row of copper bowls and tankards which had been his grandfather’s.

Nancy had been keeping the mill room in order ever since she was twelve years old. There was nothing downthere that could be damaged or broken, the Mistress had remarked to Till; yet the work would be training of a sort.

This morning Till examined everything critically; the bed-cords, the sheets and blankets, the hand washbasin, the drawer with soap and towels for the miller’s private use. She couldn’t have kept the room better herself, she thought. On her way back to the house Till fell to wondering for the hundredth time why Nancy had fallen out of favour with the Mistress. To be sure, until lately Miss Sapphy had pampered the girl too much; but it wasn’t a Dodderidge trait to turn on anybody they had once taken a fancy to. Nancy herself, Till knew, suspected fat Lizzie as the trouble-maker, but she had never said why.

Old Washington could have given Till some hint as to how this change in the Mistress had come about; but Washington was close-mouthed. Long service had taught him that tattling was sure to get a house-man into trouble.

Nearly a year ago, in the month of May, an unfortunate incident had occurred. The Mistress, sitting at the table after her husband had finished his breakfast and gone to the mill, heard loud voices from the kitchen. The windows and doors were open to let the freshspring air blow through the house. She recognized fat Lizzie’s rolling tones and suspected she was bullying one of the other servants. Washington was standing behind the Mistress’s chair. She beckoned him to help her rise, took his arm, and limped painfully to the back door.

This was what she heard (not Lizzie’s voice, now, but Nancy’s): "You dasn’t talk to me that way, Lizzie. I won’t bear it! I’ll go to the Master."

Then Lizzie, with a big laugh: "Co’se you’ll go to Master! Ain’t dat jest what I been tellin’ you? You think you mighty nigh owns dat mill. Runnin’ down all times a-day and night, carryin’ bokays to him. Oh, I seen you many a time! pickin’ vi’lets an’ bleedin’-hearts an’ hidin’ ’em under your apron. Yiste’day you took him down de chicken livers fur his lunch I fried for Missus! You’re sure runnin’ de mill room wid a high han’, Miss Yaller Gal, an’ you’se always down yonder when you’se wanted."

"’Tain’t so! I always hurries. I jest stays long enough to dust de flour away dat gits over everything, an’ to make his bed cumfa’ble fur him."

"Lawdy, Lawdy! An’ you makes his bed cumfa’ble fur him? Ain’t dat nice! I speck! Look out you don’t do it once too many. Den it ain’t so fine, when somethin’ begin to show on you, Miss Yaller Face."

Through Lizzie’s lewd laughter broke the frantic voice of a young thing bursting into tears.

"I won’t stay here to listen to your nasty tongue! An’ him de good kind man to every nigger on de place. Shame on you, you bad woman!" Nancy rushed out of the kitchen sobbing, her face buried in her hands. She did not see her mistress standing in the doorway.

That very night Nancy was ordered to bring her straw tick up from Till’s cabin and sleep on the floor outside Mrs. Colbert’s bedroom door. She had been sleeping there ever since.

Through the summer, lying outside the Mistress’s door was not a hardship,—the girl had always slept on the floor. But when the winter came on, drafts blew through the long hall up at the big house, and even when she went to bed with her yarn stockings on and had heavy quilts over her, the cold kept her awake in the long hours before daybreak.

On nights when the miller did not go down to the mill, but slept in the Mistress’s room, and she was not supposed to need a servant ready at call, Nancy was sent running across the back yard to Till’s cabin, with her tick in her arms and a glad smile on her face. She loved that cabin, and all her mother’s ways. Till and old Jeff slept in the "good room" where there was a bedstead.Nancy spread her mattress on the kitchen floor, where she could watch the firelight flicker on the whitewashed walls as the logs burnt down. There she felt snug, like when she was a little girl. And toward morning she could hear all the homelike noises close at hand: Uncle Jeff snoring, the roosters crowing, the barn dogs barking. Her mammy would maybe come and put an extra quilt over her, and then she would drift off to sleep again.

A few days after Nancy had begun to make her bed outside her mistress’s door, the miller came to his breakfast one morning with a grim face. He greeted his wife soberly, sat down, and began to eat his ham and eggs in silence. When his second cup of coffee had been put at his place, he said quietly:

"You may go, Washington, until your mistress rings for you."

As soon as they were alone he lifted his eyes and looked across the table at his wife.

"Sapphira, do you know who has been coming down to clean the mill room lately?"

She looked up artlessly from her plate. "I think it was Bluebell. Don’t tell me she meddled with your things!"

"Bluebell; the laziest, trashiest wench on the place!"

"She’ll learn, Henry. If she doesn’t take hold, I’ll send Till down to make her step lively."

"She’ll do no stepping at all in the mill. If I see her there again, I’ll put her out. Nancy is to look after the mill room, as she always has done."

"But Nancy is old enough now to be trained for a parlour maid. If you won’t have Bluebell, try one of Martha’s girls. Till has all the housekeeping to do now, since I can’t get about. She needs Nancy here."

The miller was silent for a moment. His first flush of anger had passed. When he looked up again, he spoke quietly.

"Of course the blacks on this place belong to you, and I have never interfered with your management of them. But I warn you, Sapphira, that I will not have any of the wenches coming down to the mill. I don’t mean to break in another girl. Nancy is quiet and quick. She knows how I want things, and she puts them that way. I must ask you to spare her to me for a little while every morning."

Mrs. Colbert laughed lightly. "Oh, certainly, if you feel that way about it. Why take a small matter so seriously? It’s of no importance to me who makes my bed," she added with just a shade of scorn.

"Yes, it is. You wouldn’t have anybody but Till fix your room. It’s not my bed I care about. It’s the girl’s quiet ways and respectful manner, and that she never stops to gossip with my mill-hands."

He said no more, but went out into the hall and took up his wide-brimmed hat—this morning white with two days’ flour-dust.

When Nancy first began to take care of the mill room, she usually went down while the Master was at breakfast. Sometimes she had to go earlier, to take his freshly ironed shirts and underwear and put them in his chest of drawers before he locked it for the day. After a while she fell into the habit of going early, because she got a smile, along with his "Good morning, child." After her mother and Mrs. Blake, there was no one in the world she loved so much as the Master. She had never had a harsh word from him—not many words at any time, to be sure. But his kindly greeting made her happy; that, and the feeling she was of some use to him.

Once, on a spring morning when the yellow Easter flowers (jonquils) were just bursting into bloom, she had gathered a handful on her way to the mill and put them in one of the copper tankards on the shelf. Shethought the yellow flowers looked pretty in the copper. The miller had already gone to breakfast. She didn’t know whether she ought to leave them there or not; he might not like her taking such a liberty.

The next morning the flowers were still in the tankard. The miller was stropping his razor. He turned round as she came in.

"Good morning, child. I wonder who brought me some smoke-pipes down here?"

Nancy’s yellow cheeks blushed pink. "I just happened to see ’em as I was runnin’ down, Mr. Henry. I put ’em in water to keep ’em fresh. An’ I reckon I forgot ’em."

"Just leave them there. I like to see flowers in that stein. My father used to drink his malt out of it."

After that, when she could do so unobserved, Nancy often stopped to pick a bunch of whatever flowers were coming on, and took them down to the mill under her apron.

The miller was a little disappointed when Nancy did not tap at his door before he started for the house, but he never suggested that she come earlier, or delayed his departure by one minute. His silver watch was always beside him while he shaved, and when the hand reached five minutes to eight he put on his hat. The Colbert menhad a bad reputation where women were concerned. That was why, in spite of her resemblance to the portrait painter from Cuba, Nancy was often counted as one of the Colbert bastards. Some people said Guy Colbert was her father, others put it on Jacob. Although Henry was a true Colbert in nature, he had not behaved like one, and he had never been charged with a bastard.