McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 42 (March 1914): 95-108.

MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY

IN THE FIRST FIVE CHAPTERS OF HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY MR. MC CLURE TOLD OF HIS EARLY CHILDHOOD IN IRELAND, THE DEATH OF HIS FATHER, AND HIS VOYAGE TO AMERICA, WHEN HE WAS NINE YEARS OLD, WITH HIS MOTHER AND YOUNGER BROTHERS; OF THE FAMILY'S STRUGGLE FOR A LIVELIHOOD IN THE NEW COUNTRY; AND OF HIS OWN EFFORTS TO GET AN EDUCATION. WHEN HE WAS SEVENTEEN HE WENT TO GALESBURG, ILLINOIS, AND WORKED HIS WAY THROUGH KNOX COLLEGE. HE THEN MADE HIS WAY TO BOSTON AND EDITED A BICYCLING MAGAZINE FOR THE POPE MANUFACTURING COMPANY. HE HAD BEEN ENGAGED FOR SEVEN YEARS TO HARRIET HURD, DAUGHTER OF PROFESSOR HURD OF KNOX COLLEGE. THEY WERE NOW MARRIED, AND, AT THE INVITATION OF MR. ROSWELL SMITH OF THE CENTURY MAGAZINE, THEY MOVED TO NEW YORK. AFTER A YEAR OF STRUGGLE, MR. MC CLURE LAUNCHED HIS NEWSPAPER SYNDICATE.

THIS was my situation during those first months that I was starting the syndicate. I was twenty-seven years old, with a wife and baby; I had no business friends or connections in New York; and I was launching a new business that had never been tried before. I was utterly without resources. I had not $25 in the bank, and I had no relatives who could help me. At the end of the first week of the syndicate I was $50 behind. I passionately believed in the idea, but there were times when I knew that it could not succeed because too much depended upon it. It wasn't as if I had had money enough to live on for six months while I gave the thing a trial. We had not even a day's credit at the grocery shop. We were cooking on a one-burner oil-stove, an old one, badly worn, and I did most of the washing in order to save my wife.

I was sure enough of the idea, but I was not  sure that I was the man who could carry it out. There seemed no chance for anything

new. Surely, I used to tell myself, if the thing were worth doing, somebody would

have done it before. I used to go out and walk about the city, anguishing over the

thing. New York looked full; the world looked full. What chance was there for a little

new business with no capital behind it, with only one young man behind it? And I had

less confidence in that young man than I had in any other, because I knew him better

than I knew any other man. I looked about over a city of six-story buildings—great

stretches of the upper West Side were unoccupied, and Harlem was a country district—a

city lit by gas, where all the cars were drawn by horses except the elevated trains,

which were pulled by little steam-engines; and it seemed as if everything had been

done, as if there were no further

sure that I was the man who could carry it out. There seemed no chance for anything

new. Surely, I used to tell myself, if the thing were worth doing, somebody would

have done it before. I used to go out and walk about the city, anguishing over the

thing. New York looked full; the world looked full. What chance was there for a little

new business with no capital behind it, with only one young man behind it? And I had

less confidence in that young man than I had in any other, because I knew him better

than I knew any other man. I looked about over a city of six-story buildings—great

stretches of the upper West Side were unoccupied, and Harlem was a country district—a

city lit by gas, where all the cars were drawn by horses except the elevated trains,

which were pulled by little steam-engines; and it seemed as if everything had been

done, as if there were no further

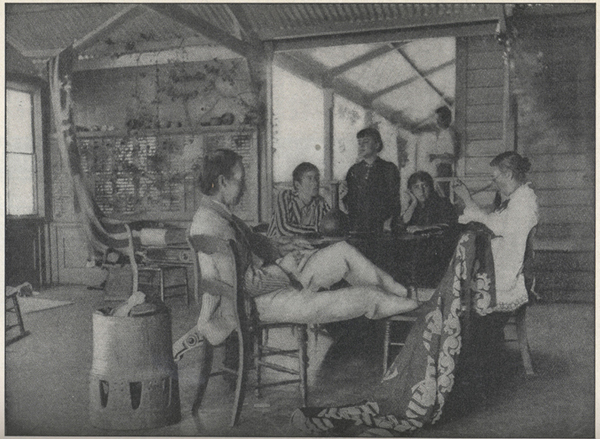

THE STEVENSON HOUSEHOLD

Mr. Stevenson sits in the foreground. The lady sewing is his mother; the one sitting

next her is his wife; while the one standing is his stepdaughter, Mrs. Strong. The

man opposite him is his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne

possibilities of expansion. Every young man has to face and overcome that delusion

of the completeness of the world. It is like a wall too high to climb over, a hedge

too dense to wriggle through. The Columbia College buildings were then on Forty-ninth

Street, very near our flat, and I used to get so low in my mind that I would go over

there and try to get a job in the Library. I remember, at one time I agreed to select

and file newspaper clippings for the librarian for $3.50 a week. These fits of desperation

came on when I had no money to get out of town to see editors, no chance to extend

the business or to talk over my ideas with newspaper men. There is nothing like the

enthusiasm and appreciation of another mind to help a new idea to develop.

THE STEVENSON HOUSEHOLD

Mr. Stevenson sits in the foreground. The lady sewing is his mother; the one sitting

next her is his wife; while the one standing is his stepdaughter, Mrs. Strong. The

man opposite him is his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne

possibilities of expansion. Every young man has to face and overcome that delusion

of the completeness of the world. It is like a wall too high to climb over, a hedge

too dense to wriggle through. The Columbia College buildings were then on Forty-ninth

Street, very near our flat, and I used to get so low in my mind that I would go over

there and try to get a job in the Library. I remember, at one time I agreed to select

and file newspaper clippings for the librarian for $3.50 a week. These fits of desperation

came on when I had no money to get out of town to see editors, no chance to extend

the business or to talk over my ideas with newspaper men. There is nothing like the

enthusiasm and appreciation of another mind to help a new idea to develop.

Hard Sledding

I remember, one Saturday afternoon Mrs. McClure and I started for a walk in Central Park. I was wheeling the baby in the carriage, and we were talking about what we were going to do to get provisions to last over Sunday. I had no money at all, and, as I have said, we had no credit. As we left the apartment-house I was met by the postman with a registered letter. It contained an unexpected ten-dollar bill from a paper in New Orleans. We felt as if the future were provided for.

I never kept books; a few notes jotted down from time to time kept me informed as to my accounts. I had never had a bank account before, and I was always having to pay out an extra dollar and a half for fees on over-drafts. I paid my authors as I could. Some writers were very agreeable about waiting, and others were not so long-suffering. Once, when I was out of town selling my stuff to editors, Edgar Fawcett's valet came to our flat, and sat there all day for three days in succession to collect for a story of Fawcett's. Mrs. McClure told him she had no money, but he came back just the same.

When I made up my accounts on the first of April, five months after the syndicate was started, the various newspapers I served owed me $1000, and I owed $1500 to authors. Just at that critical time a two-part story came in from Harriet Prescott Spofford, with a note saying that this story was a present—that she had meant it for a New Year's present, but she hoped it wouldn't be too late. That story was like a buoy thrown to an exhausted swimmer, that holds him up until he can get his breath. I sold it for $275. On the first of June my accounts showed a balance of $161 in my favor.

And yet, all this time we were very happy. I was rich in ideas and in hope, and my wife believed in my ideas and in me. Mrs. McClure attended to all the business when I was off on my trips to see newspaper editors. She wrote a great many of my business letters, prepared copy for the printers, and translated French and German short stories, which I sold in my regular syndicate service. Postage was one of the heavy drains upon our purse, and when we had to decide between postage stamps and steak for dinner, she always declared for the postage.

At one stage of the game we took a "mealer," a fine young man whose sister had been a fellow teacher of Mrs. McClure's at Abbot Academy. He helped us cook on a new gas-burner, and accommodated himself to our circumstances with great zest. Once, when I was starting off on a trip to encourage the editors, I wore one high shoe and one low one, because the mates of both were unfit to be seen. On that same trip I had the misfortune to lose $45 in cash—simply lost the stuff. I was always careless about money, and in Cincinnati I had $45 which I had that day got from the Indianapolis News, in my trousers pocket, along with some stamps. I pulled out the money and stamps to mail a letter, and never saw the money again. I had to borrow money to get home on from the editor of the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette. When I reached home and told Mrs. McClure about it, we decided to have a good dinner and forget it. We had a saying, in our flat, that if you didn't mind a thing, it never really hurt you. We were never crushed or poor in spirit. We never let our poverty make us mean. That is the greatest hurt that poverty can inflict upon people. Once the syndicate got fairly started, after it had lived a few months indeed, I was sure that I could make it go. After that I was seldom discouraged. I was doing the work I loved and developing my own idea, and I always felt cheerful. So did my wife.

Getting the Syndicate on Its Feet

I had no vacations except Sunday, and then Mrs. McClure and I usually took the baby and went off on a boat somewhere, or walked in the Park. Our real pleasure, however, was the new business itself. We had it there in the flat with us; we ate in the office; the syndicate was a member of the household. Mr. Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, came to the flat to see me on business about this time, and he wrote an article on the contiguousness of my business and domestic operations, saying that the dinner and the baby and the ink-bottles were inextricably confused.

Between us, Mrs. McClure and I did every kind of office drudgery, all the things that in an ordinary business there are half a dozen people to do. We did the office-boy's work and the clerk's work and the stenographer's work. Our office hours were from eight in the morning to ten o'clock at night. When things were all at sixes and sevens, and the business seemed to be fairly tumbling about my ears, I have sat down after dinner at night, and written by hand as many as forty letters to editors, outlining glowing plans for the future operations of the syndicate. The risks were always immediate and great. Even after I was selling to newspapers enough to feel that I could count on a profit of $50 a week, a paper taking $25 service was likely at any time to discontinue its patronage, taking half of my net profits.

When I was serving, say, forty papers, forty copies of the story for any given week

had to be sent out, and the copies for the Pacific Coast papers had to be mailed ten

days before the date of their publication. Making these duplicates was always a harassing

question. If I had had them set by a job printer and galley proofs run off, the  "MRS. STEVENSON had many of the fine qualities that are usually attributed to men rather than women:

a fair-mindedness, a large judgment, a robust, inconsequential philosophy of life,

without which she could not have borne, much less shared with a relish equal to his

own, Stevenson's wandering, unsettled life, his vagaries, his gipsy passion for freedom" cost of composition would have more than eaten up any possible profits. So it was

my custom to supply the service free to one newspaper that would set from the author's

copy and supply me with the requisite number of galley proofs to be sent to the other

newspapers, where the story was set up for each paper from these proofs. Often the

paper that supplied these proofs would be late; sometimes, after I had spent an anxious

day or two waiting for them, they would come just in time for me to rush them off

on the first mail. Sometimes they would be too late altogether for the more distant

papers, and I would lose heavily for that week, and perhaps lose the patronage of

a paper that had been disappointed. So we lived in turmoil.

"MRS. STEVENSON had many of the fine qualities that are usually attributed to men rather than women:

a fair-mindedness, a large judgment, a robust, inconsequential philosophy of life,

without which she could not have borne, much less shared with a relish equal to his

own, Stevenson's wandering, unsettled life, his vagaries, his gipsy passion for freedom" cost of composition would have more than eaten up any possible profits. So it was

my custom to supply the service free to one newspaper that would set from the author's

copy and supply me with the requisite number of galley proofs to be sent to the other

newspapers, where the story was set up for each paper from these proofs. Often the

paper that supplied these proofs would be late; sometimes, after I had spent an anxious

day or two waiting for them, they would come just in time for me to rush them off

on the first mail. Sometimes they would be too late altogether for the more distant

papers, and I would lose heavily for that week, and perhaps lose the patronage of

a paper that had been disappointed. So we lived in turmoil.

My First Authors

Among my first authors were George Parsons Lathrop, Frank R. Stockton, Julian Hawthorne, Harriet Prescott Spofford, H. C. Bunner, Louise Chandler Moulton, and Henry Harland, who became famous about that time as the author of "As It Was Written," a novel which he published under the name of Sidney Luska. Harland was the son of a New York lawyer. He afterward went to England and became editor of the Yellow Book, considered a very bold publication in those days, a rather daring book to have on one's table. Every one remembers his success with "The Cardinal's Snuff Box."

Edmund Clarence Stedman

THE HOUSE in Saranac where Stevenson lived the winter of 1887; from a pencil drawing by J.

N. Vandergrift. Here Mr. McClure went to see Stevenson to arrange for the serial publication

of "St. Ives" in MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE; and it was here that, one memorable evening, Stevenson planned out his South Sea

cruise introduced me to Harland when his first novel, "As It Was Written," was being talked

about everywhere. Harland was working in a downtown office then, and he did his writing

at night. He often used to write until four o'clock in the morning. He was a young

man of twenty-four or twenty-five then, with a manner at once ingratiating and sincere,

an inveterate smoker of choice cigarettes. I bought some of his short stories for

the syndicate, and serialized one novel, "The Yoke of the Thorah." All his early stories

were about Jewish life.

THE HOUSE in Saranac where Stevenson lived the winter of 1887; from a pencil drawing by J.

N. Vandergrift. Here Mr. McClure went to see Stevenson to arrange for the serial publication

of "St. Ives" in MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE; and it was here that, one memorable evening, Stevenson planned out his South Sea

cruise introduced me to Harland when his first novel, "As It Was Written," was being talked

about everywhere. Harland was working in a downtown office then, and he did his writing

at night. He often used to write until four o'clock in the morning. He was a young

man of twenty-four or twenty-five then, with a manner at once ingratiating and sincere,

an inveterate smoker of choice cigarettes. I bought some of his short stories for

the syndicate, and serialized one novel, "The Yoke of the Thorah." All his early stories

were about Jewish life.

Harland had been married but a short while, and was living in his father's house on East Fifty-fourth Street, one of a row of houses overlooking the East River. Mrs. McClure and I got to know him and his wife very well. We were all young people starting out in life, and most of the men with whom my business brought me in contact were older men, already established, like Mr. Stedman, Mr. Howells, and Mr. Stockton. As for the older editors, they all believed that there would never be any new magazines in the world—that Harper's and the Century and the Atlantic could consume all the stories that would ever be written in America, and that if I went on buying stories for my syndicate there would not be enough to go around. Harland and I looked at some of these things differently, and we found a good deal in common. One summer, when he and his wife went away, Mrs. McClure and I lived in their apartments on the upper floors of the Harland house.

Henry Harland and the "Yellow Book"

After Harland went to England he changed greatly, and he quite outgrew his early stories. Once, when I went to see him at his place in Kensington, I threatened to republish all of his Sidney Luska stories under his own name. "If you do, Sam," he said, "I'll publish a statement that Sam McClure is the author of every one of them!" Harland and his Yellow Book set were so far advanced at that time that they considered George Meredith very old-fashioned indeed. When I objected to the ethics of a story published in the Yellow Book, Harland rolled on the floor with laughter. "The same old Sammy!" he chuckled. "The same old Sammy!" But, in spite of their advanced ideas, the Yellow Book did not rejuvenate English fiction. The new movement had begun in quite another quarter, and was identified rather with the name of Robert Louis Stevenson.

The last time I ever saw Harland was in San Remo, Italy. He was as delightful a companion as ever. I noticed that he had shaved off his moustache, and I asked him why he had done it. He smiled drolly and said: "Sam, the darned thing was getting white!"

I Write a Series of Articles on Cookery

The summer that I was living in Harland's apartments, I was writing a series of cookery

articles for the syndicate, signing myself "Patience Winthrop," and hoping that under

this pseudonym I would be taken for a New England housewife. The newspapers were just

beginning to publish cookery articles at that time; it was a new thing; and mine were

very successful. It came about in this way. When we were married, Mrs. McClure, having

always been a student and teacher, did not know how to cook. After the syndicate got

a little start and we began to have time to take such things into account, I went

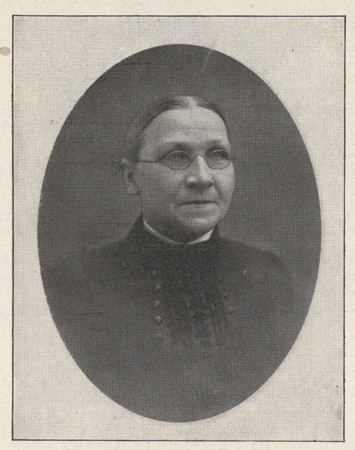

to the kitchen  MR. MCCLURES'S MOTHER

of the Astor House and learned how the best cooking in New York was done. I learned

how to do a few things as well as they could be done, and learned a few basic principles—for

instance, that meats should be cooked slowly, by a moderate heat, that eggs cooked

for eight minutes in water below boiling heat (at 170° F.) are much better than eggs

cooked for two minutes in boiling water.

MR. MCCLURES'S MOTHER

of the Astor House and learned how the best cooking in New York was done. I learned

how to do a few things as well as they could be done, and learned a few basic principles—for

instance, that meats should be cooked slowly, by a moderate heat, that eggs cooked

for eight minutes in water below boiling heat (at 170° F.) are much better than eggs

cooked for two minutes in boiling water.

After my syndicate had been going for a year, I felt that I could afford to take a downtown office. I rented a room in the Morse Building, on the corner of Nassau and Beekman streets, opposite the Tribune Building, and hired a stenographer. Among the people who wrote for me at this time were Octave Thanet, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Mrs. Burton Harrison, Sarah Orne Jewett, Brander Matthews, Joel Chandler Harris, Charles Egbert Craddock, and Margaret Deland.

After the syndicate had been running for two years, John S. Phillips came home from Germany. When we left the Wheelman in Boston, Mr. Philips had gone to Harvard for two years, and after taking his degree there had gone to study at Leipsic. He remained there a year, and then came to New York, where he joined me in the syndicate business, coming in at a salary, and becoming my partner in the business seven years afterward. When Mr. Phillips joined me, I was under the impression that I was about $1800 ahead, but, on making a careful examination of my affairs, he discovered that I was only $600 ahead. I drew no specified salary from the business; I owned the syndicate, and I simply took out money as I needed it. A very bad method; for, while I thought I was taking about $3000 a year for my family expenses, I was probably taking out $4000 or $5000. Expenses were heavy during those years, as my four children were born between 1884 and 1890.

Getting Syndicate Ideas

Mr. Phillips very soon took over the entire office management of the business, for which he was much better fitted than I. He had an orderly and organizing mind—which I had not,—and he had had a much wider education. I usually lost interest in a scheme as soon as it was started, and had no power of developing a plan and carrying it out to its least detail, as Mr. Phillips had. His extraordinary competence in the office left me free to move about the country, seeing editors and authors and keeping in touch with both ends of the market. I found out what people were writing and what people were reading, and in which of the happenings in the world people took the keenest interest. Often I was able to suggest to writers a subject profitable to them and to me. I sometimes spent as many as seventeen successive nights in sleeping-cars, when I was traveling for the syndicate. I never got ideas sitting still. I never saw so many possibilities for my business or had so many editorial ideas as when I was hurrying about from city to city, talking with editors and newspaper men. The restlessness which had mastered me as a boy always had the upper hand of me, and it was my good fortune that I could make it serve my ends. Whatever work I have done has been incidental to this foremost necessity to keep moving.

Of course, as soon as my syndicate began to pay, other syndicates were started. The most powerful of these was started by Allan Thorndyke Rice, editor of the North American Review. My friends and many of the editors I served thought such a competitor would be too much for me. I remember that at this time Miss Sarah Orne Jewett, who wrote for the syndicate and took a friendly interest in my business, wrote me to ask whether I could not form some combination with Mr. Rice to avoid being wiped out. Mr. Rice's syndicate was very strong for a time, but eventually it died out without seriously cutting into my business. At one time the St. Jacob's Oil people organized a syndicate service, furnishing matter to the newspapers for $75 a week and guaranteeing to place with each paper that took the service advertising of their oil enough to cover the cost of the service, thus giving it to the paper for nothing. This sounded formidable, but I was sure it would not succeed, for I knew there was small likelihood of the St. Jacob's Oil people finding an editor who could buy such material as would be of any value to the newspapers. And, indeed, their syndicate had but a short life.

My First Call upon Stevenson

The Bacheller Syndicate, organized by Mr. Irving Bacheller, author of "Eben Holden," proved to be my strongest competitor. In 1887 I heard that Mr. Irving Bacheller was going abroad to get material from English writers, and I thought I had better go also. Before I sailed, Charles de Kay, brother-in-law of Richard Watson Gilder, told me about a very remarkable story of adventure, "Kidnapped," that had been published in England. I read the book, was greatly delighted with it, and as soon as I got to London, in February, 1887, I wrote to the author at Bournemouth, where I understood he was staying for his health. To this letter I got no reply. But late in the summer of that year, a young man came into my office in the Tribune Building, in New York, asked to see me, and introduced himself as Lloyd Osbourne. He said he was the stepson of Robert Louis Stevenson, and that Mr. Stevenson had received a letter from me which he had never been able to answer because he had mislaid it and did not remember the address; but that Stevenson was in New York, at the Hotel St. Stephen on Eleventh Street, and would be glad to see me.

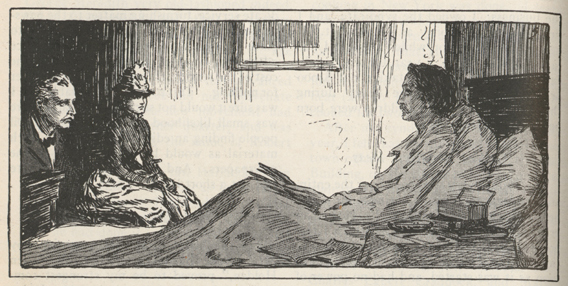

Mrs. McClure and I called upon Stevenson, accordingly, and were taken to his room, where he received us in bed, very much in the attitude of the St. Gaudens medallion, for which he was then posing. We had a pleasant call, but there was nothing very unusual about it. Stevenson, though he was in bed, did not seem ill; he looked frail but not sick. The thing about his appearance that most struck me was the unusual width of his brow, and the fact that his eyes were very far apart. He wore his hair long. Stevenson was already a famous man; the publication of "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" had made him so.

"We were taken to his room, where he received us in bed, very much in the attitude

of the St. Gaudens medallion. He did not seem ill; he looked frail, but not sick"

"We were taken to his room, where he received us in bed, very much in the attitude

of the St. Gaudens medallion. He did not seem ill; he looked frail, but not sick"

I did not see him again before he went to the Adirondacks. In October I went up to Saranac to see him, commissioned by Mr. Pulitzer of the World to offer him $10,000 a year for a short essay every week, to be published in the World. He had already such a "news value" as to be worth that to a paper.

Brander Matthews had told me about three long adventure stories that Stevenson had published in Henderson's Weekly, an English paper of about the character of the New York Ledger in this country. These stories were "Treasure Island," "Kidnapped," and "The Black Arrow." He had received only $500 apiece for them. They had not appeared over his own name, but were signed with his pseudonym, "Captain North." I believe some of his literary friends in England were very much opposed to his publishing adventure stories, such as "Kidnapped," under his own name, as they thought it might compromise his future.

"Kidnapped" and "Treasure Island" had already been republished in book form, but "The Black Arrow" had never been resurrected, and lay unknown to the world in the back files of Henderson's Weekly. When I went up to Saranac for Mr. Pulitzer, I told Stevenson that I would publish "The Black Arrow" serially in my newspaper syndicate, and pay him a good price for it. Mrs. Stevenson was not at home then, and Stevenson said he could not decide the matter without consulting her, as she had never liked the story, and he thought she might be unwilling to have it republished under his own name. She never was much in favor of the project, but gave her consent.

Stevenson had no copy of the story, but he sent to England and got the files of Henderson's Weekly which contained the story, and sent them to me. I read the story, and told him that I would take it if he would let me omit the first five chapters. He readily consented to this. Like all writers of the first rank, he was perfectly amiable about changes and condensations, and was not handicapped by the superstition that his copy was divine revelation and that his words were sacrosanct. I never knew a really great writer who cherished his phrases or was afraid of losing a few of them. First-rate men always have plenty more.

Stevenson's news value was such that it was a great thing for the syndicate to be able to offer the newspapers a serial of adventure by Robert Louis Stevenson. But we had no copyright law then, and if I published the story under its original title, "The Black Arrow," any American paper might cut in, get a file of Henderson's Weekly, and come out ahead of me. In the hope of keeping possible pirates in the dark, I advertised and published the story under the title "The Outlaws of Tunstall Forest." I had it illustrated with line drawings by Will H. Low, an old friend of Stevenson's since their Barbison days. That was the first illustrated story we ran in the syndicate, and it brought in more money than any other serial novel we ever syndicated.

While it was running in the syndicate under a new title, Stevenson arranged for the book publication of "The Black Arrow" with Charles Scribner's Sons. His friend William Archer went over the proofs for him in October. It was in April of that year, at Saranac, that he wrote the dedication of the book, inscribing it to Mrs. Stevenson, the "Critic on the Hearth."

"No one but myself," this dedication begins, "knows what I have suffered, nor what my books have gained, by your unsleeping watchfulness and admirable pertinacity. And now here is a volume that goes into the world and lacks your imprimatur; a strange thing in our joint lives; and the reason of it stranger still! I have watched with interest, with pain, and at length with amusement, your unavailing attempts to peruse The Black Arrow; and I think I should lack humour indeed, if I let the occasion slip and did not place your name in the fly-leaf of the only book of mine that you have never read—and never will read."

The Offer for "St. Ives"

While the preparations for this were going on, I went up to Saranac several times to see Stevenson. He was living in the Baker cottage, a rented furnished house near an ice-pond with trees around it. I remember once I took up a pair of skates for him and a pair for myself, and we skated. He was then going over Lloyd Osbourne's story, "The Wrong Box." Osbourne had written the story throughout, and Stevenson went over it and touched it up. I read it, and thought it a good story for a young man to have written; but I told Stevenson that I doubted the wisdom of his putting his name to it as joint author. This annoyed him, and he afterward wrote me that he couldn't take advice about such matters. He told me, during that visit, that he had two new novels in mind, one of them a sequel to "Kidnapped." The other was "St. Ives." I told him that I would take either story and pay him $8000 for it. He blushed and looked confused and said that his price was £800 ($4000), and that he must consult his wife and Will Low before he made any agreement. He went on to say that he didn't think any novel of his was worth as much as $8000, and that he wouldn't be tempted to take as much money as that for a novel, if it were not for a plan he had in mind. He was always better at sea, he said, than anywhere else, and he wanted to fit up a yacht and take a long cruise and make his home at sea for a while.

When I left Saranac that time, Stevenson had agreed to let me have the serial rights

of  "I was wheeling the baby in the carriage, and we were talking about what we were going

to do to get provisions to last over Sunday. I had no money at all, and we had no

credit"

a novel for $8000. About two weeks later he wrote to his friend Charles Baxter:

"I was wheeling the baby in the carriage, and we were talking about what we were going

to do to get provisions to last over Sunday. I had no money at all, and we had no

credit"

a novel for $8000. About two weeks later he wrote to his friend Charles Baxter:

I am offered £1600 [$8000] for the American serial rights on my next story! As you say, times are changed since the Lothian Road. Well, the Lothian Road was grand fun, too; I could take an afternoon of it with great delight. But I'm awfu' grand noo, and long may it last!

His exultation, however, was short-lived. When he made this agreement with me, he was already under contract with Charles Scribner's Sons to let them handle all his work in this country. Two days after the above letter to Baxter, he wrote to Mr. Charles Scribner:

Heaven help me, I am under a curse just now. I have played fast and loose with what I said to you, and that, I beg you to believe, in the purest innocence of mind. I told you that you should have the power over all my work in this country; and about a fortnight ago, when McClure was here, I calmly signed a bargain for the serial publication of a story. You will scarce believe that I did this in mere oblivion; but I did; and all I can say is that I will do so no more, and ask you to forgive me.

Some weeks later Stevenson wrote to Henley:

I have had the most deplorable business annoyances too; have been threatened with having to refund money; got over that; and find myself in the worse scrape of being a kind of unintentional swindler.

The novel that finally fulfilled this contract between Stevenson and me was "St. Ives." At the time when I made it, I knew nothing of his agreement with Scribner's. He was the last man to inform one about his business affairs, even when he was informed as to them himself, which was not often. He says, in a letter to Mr. Burlingame, editor of Scribner's Magazine, written shortly after he made this contract with me:

I have no memory. You have seen how I omitted to reserve the American rights in "Jekyll"; last winter I wrote and demanded as an increase, a less sum than had already been agreed upon for a story that I gave to Cassell's. For once that my forgetfulness has, by a cursed fortune, seemed to gain, instead of lose, me money, it is painful that I should produce so poor an impression on the mind of Mr. Scribner.

We Plan the South Sea Cruise

The evening of the day on which I offered Stevenson an increase in his serial rates was the first time I ever heard him talk of his desire to take a long ocean cruise. He told me again that he didn't think his novels were worth what I had offered him, and that the consideration which most influenced him to accept such a price was his wish to take a yacht and live for a while at sea. I thought at once of "An Inland Voyage" and "Travels With a Donkey," and told him that if he would write a series of articles describing his travels, I would syndicate them for enough money to pay the expenses of his trip. I think the South Seas must have been mentioned that evening, for I remember that after I returned to New York I sent him a number of books about the South Seas, including a South Pacific directory. The next time I went to Saranac, we actually planned out the South Pacific cruise, talking about it until late into the night.

That was a night not easily forgotten. Stevenson's imagination was thoroughly aroused. He walked up and down the floor, or stood leaning against the mantel, inventing one project after another. We planned that when he came back he was to make a lecture tour and talk on the South Seas; that he was to take a phonograph along and make records of the sounds of the sea and wind, the songs and speech of the natives, and that these records were to embellish his lectures. We planned the yacht and the provisioning of the yacht, and all possible adventures. We planned a good deal more than a man could ever accomplish, but it was all real that night, and out of that talk came the South Sea cruise. That was just before I went to London to syndicate "The Outlaws of Tunstall Forest" in England, and I never saw Stevenson again. When I returned to New York from London, he was in San Francisco, fitting out the yacht Casco before his departure to the South Pacific, from which he never returned.

His "South Sea Letters" ran for about a year in the syndicate. They were, on the whole, a disappointment to newspaper editors, for they revealed a side of Stevenson with which the public was as yet not much acquainted. There were two men in Stevenson—the romantic adventurer of the sixteenth century, and the Scotch Covenanter of the nineteenth century. Contrary to our expectation, it was the moralist and not the romancer which his observations in the South Seas awoke in him, and the public found the moralist less interesting than the romancer. And yet, in all his essays, the moralist was uppermost.

Stevenson was the sort of man who commanded every kind of affection: admiration for his gifts, delight in his personal charm, and respect for his uncompromising principles. Underneath his velvet coat, his gaiety and picturesqueness, he was flint. It was probably this unusual combination of qualities in him that made one eager to serve him in every possible way. I remember saying to Mr. Phillips once: "John, I want the syndicate business to be run exactly as if it were being conducted for the benefit of Robert Louis Stevenson." And that was the way I felt about him.

Henry James and Stevenson

Before I sailed for London, Stevenson gave me letters to a number of his friends there—Baxter, W. E. Henley, Sidney Colvin, R. A. M. Stevenson, and others. I found most of Stevenson's set very much annoyed by the attention he had received in America. There was a note of detraction in their talk which surprised and, at first, puzzled me. Henley was particularly emphatic. He had a double grievance: that a nation whom he despised as a rude and uncultivated people should presume to give Stevenson a higher place than he held in England, and the personal jealousy which he later voiced in his own writings. He believed that his own influence upon Stevenson's work was not sufficiently recognized. Some of Stevenson's London friends agreed that he was a much overrated man, and that his cousin, R. A. M. Stevenson, was the real genius of the family.

There was one most marked exception to this dissenting chorus, and that exception was Henry James, to whom Stevenson had given me a letter. I had somehow always imagined Mr. James as a rather cold and unsympathetic man, but I now found how greatly I had been mistaken. His tone about Stevenson warmed my heart. His warm human friendship was a delight after what I had been hearing. There was nothing at all critical in his attitude. He was Stevenson's friend, admirer, and well-wisher. His interest in Stevenson's health, his work, his plans for the future, was wholly affectionate, wholly disinterested. His loyal, generous feeling I have never forgotten. He questioned me minutely about everything pertaining to Stevenson. His interest was keen, sympathetic, personal.

During that visit to London I learned to appreciate one of Stevenson's great sources of discouragement. Some of his friends there, those in whose critical powers he had most faith, were always condemning his new book, whatever it was. They could stand for what was already printed, but when he sent them the manuscript of a new work, they usually declared that that was fatal, that would be the end, and entreated him, for the sake of his reputation, not to publish it. One benefit of his life in the South Seas was that it placed him farther from these inhibiting influences, and left him freer to work out what was in him as best he could in the short life allotted to him.

Although some of Stevenson's friends were jealous of him in a small way, most of them were jealous for him in a very high way. Serious men took him more seriously than they took other writers of fiction. Critics like Mr. Colvin felt that he had a very precious gift, something to be preserved for the highest uses. He was not judged with the same leniency as other writers of his time. These criticisms of his friends were often the highest expressions of their solicitude and regard; they were often very helpful to Stevenson, but sometimes disheartening. He was so sensitive to the opinions of others that an office-boy could influence him, for the moment. And yet, in the long run, he could not be influenced at all. But this susceptibility, the fact that he could be so easily discouraged by criticism, sometimes brought him great mental suffering.

Stevenson's Willingness to Be Edited

When Stevenson began to send in his "Letters from the South Seas," he told me to use my own judgment about editing them, and to cut wherever I thought it would be advantageous. After the series was well started in the syndicate, he wrote and asked me why I was not cutting the stuff down more. I have mentioned this willingness to be edited before, and I have said that all of the really first-rate writers I have known have been similarly open-minded. I must mention it again, because, somehow, young writers often have the idea that they are lowering their flag if they consent to any changes in their manuscript—that there is a mystic power in a certain order of words. My experience has been—and I think all other editors have had the same experience—that only writers of inferior talent and meager equipment feel in that way. To a man of large creative powers, the idea is the thing; the decoration of phrase is a very secondary matter. He has no feeling that, because he has set a thing down one way once, it must stand so forever. He can say the same thing in fifty different ways. If his story is loose and runs thin, he is glad to tighten it. If it is congested, and he has tried to bring out too many points, he will cut. He can afford to spare a few ideas; he has plenty. He has no feeling that he can not cut out this sentence because he will never be able to say that particular thing so well again; he knows he'll say it better. I mention Stevenson particularly, because he is acknowledged to have been an artist in words and to have achieved a more finished style than most men, and had a very particular regard for style in its high sense. But he would have been very much ashamed of a style that condensation could hurt. He often lamented that Balzac did not have somebody to edit and condense his novels for him.

In "The Dynamiters" Mrs. Stevenson actually collaborated with her husband, and she was a very strong influence in all of his work. Her criticism and suggestions had at all times great weight with him. All his more important work was done after his marriage.

Stevenson's Wife

The more I saw of the Stevensons, the more I became convinced that Mrs. Stevenson was the unique woman in the world to be Stevenson's wife. Every one knows the story of their first meeting: how, when Mrs. Osbourne was traveling in France with her daughter, Stevenson one afternoon, passing in the street, happened to look into the dining-room window of the little hotel at Grez just as Mrs. Osbourne was rising from the table; how he looked into her face for a moment, and said, when he went on up the street, that there was the only woman in the world he would ever marry.

There had been a Spanish ancestor somewhere back in Mrs. Stevenson's family, and in every other generation the strain asserted itself. She herself is a very marked Spanish type. When Stevenson met her, her exotic beauty was at its height, and with this beauty she had a wealth of experience, a reach of imagination, a sense of humor, which he had never found in any other woman. Mrs. Stevenson had many of the fine qualities that we usually attribute to men rather than to women: a fair-mindedness, a large judgment, a robust, inconsequential philosophy of life, without which she could not have borne, much less shared with a relish equal to his own, his wandering, unsettled life, his vagaries, his gipsy passion for freedom. She had a really creative imagination, which she expressed in living. She always lived with great intensity, had come more into contact with the real world than Stevenson had done at the time when they met, had tried more kinds of life, known more kinds of people. When he married her, he married a woman rich in knowledge of life and the world. Mrs. Stevenson's autobiography would be one of the most interesting books in the world.

She had the kind of pluck that Stevenson particularly admired. He was best when he was at sea, and, although Mrs. Stevenson was a poor sailor and often suffered greatly from seasickness, she accompanied him on all his wanderings in the South Seas and on rougher waters, with the greatest spirit.

A woman who was rigid in small matters of domestic economy, who insisted upon a planned and ordered life, would have worried Stevenson terribly. In his youthful tramps he liked to start out with no luggage, buying a collar here and a shirt there, as he needed them. In managing his affairs, he had, as he often said, no money-sense. I remember hearing him tell how he and Mrs. Stevenson once went to Paris for a pleasure trip. They had a £100 ($500) check and some odd money, and they meant to have a thoroughly good time and stay as long as their money held out. After a few days they found their funds running short; they couldn't imagine what they had done with it all, but there seemed to be very little money left, so they decided they had better get home while it lasted. When they got home, they found the £100 check among their papers. They hadn't cashed it at all, and didn't even know they hadn't.

In spite of his carelessness about money, and the fact that he put about $20,000 into his house in Samoa, Stevenson did so much work, and the demand for it has been so constant, that he left a large estate. A sick man of letters never married into a family so well fitted to help him make the most of his powers. Mrs. Stevenson and both of her children were gifted; the whole family could write. When Stevenson was ill, one of them could always lend a hand and help him out. Without such an amanuensis as Mrs. Strong, Mrs. Stevenson's daughter, he could not have got through anything like the amount of work he turned off. Whenever he had a new idea for a story, it met, at his own fireside, with the immediate recognition, appreciation, and enthusiasm so necessary to an artist, and which he so seldom finds among his own blood or in his own family.

After Stevenson disappeared in the South Seas, many of us had a new feeling about that part of the world. I remember that on my next trip to California I looked at the Pacific with new eyes; there was a glamour of romance over it. I always intended to go to Samoa to visit him; it was one of those splendid adventures that one might have had and did not.

One afternoon in August, 1896, I went with Sidney Colvin and Mrs. Sitwell (now Mrs. Colvin) to Paddington station to meet Mrs. Stevenson, when, after Stevenson's death, she at last returned to Europe after her world-wide wanderings, after nine years of exile. There were only the three of us there to meet her. She had come from Samoa by way of Australia, and was to land at Plymouth from a P.&O. liner. When she alighted from the boat train, I felt Stevenson's death as if it had happened only the day before, and I have no doubt that she did. As she came up the platform in black, with so much that was strange and wonderful behind her, his companion through so many years, through uncharted seas and distant lands, I could only say to myself, "Hector's Andromache!"

I got into an embarrassing predicament through syndicating Stevenson's "Outlaws of

Tunstall Forest" in England in 1888. Mr. Tilleston, a hard-headed old Yorkshireman,

had the largest syndicate business in England, and I had an agreement with him that

I was to syndicate his serial  "I used to go out and walk about the city, anguishing over the thing" novels in America, and he, in return, was to syndicate mine in England. Up to this

time no American novel had been syndicated in England, and as I had never had occasion

to fulfill my end of the agreement, I had forgotten all about it. When I came to handle

Stevenson's adventure story, I went to London and began to place the story myself.

Mr. Tilleston promptly called me to account, and we had an interview at the National

Liberal Club in which he not only demanded the English returns for the Stevenson serial,

but all the profits I had made on syndicating Tilleston material in America. I was

so remorseful and so eager to make amends for my breach of faith that I consented

to this, though it was a rather hard bargain, and paid Tilleston a sum which wiped

out a large share of whatever I had ahead.

"I used to go out and walk about the city, anguishing over the thing" novels in America, and he, in return, was to syndicate mine in England. Up to this

time no American novel had been syndicated in England, and as I had never had occasion

to fulfill my end of the agreement, I had forgotten all about it. When I came to handle

Stevenson's adventure story, I went to London and began to place the story myself.

Mr. Tilleston promptly called me to account, and we had an interview at the National

Liberal Club in which he not only demanded the English returns for the Stevenson serial,

but all the profits I had made on syndicating Tilleston material in America. I was

so remorseful and so eager to make amends for my breach of faith that I consented

to this, though it was a rather hard bargain, and paid Tilleston a sum which wiped

out a large share of whatever I had ahead.

I then immediately borrowed £100 of Tilleston, and went with Mrs. McClure on a pleasure trip to Italy. This was my first experience of Italy, and those were wonderful days. When we got to Florence, we found Timothy Cole, the engraver, there, at leisure and disposed to be our companion in our visits to the galleries. He went with us again and again to the Pitti, the Uffizi, and the Belle Arti, talking enchantingly about the pictures. His companionship was a great piece of good fortune for me, as well as a great pleasure. I had never before had time or opportunity to look at pictures, and that ten days in Florence opened a new world to me. From Florence Mrs. McClure and I went to Rome. That is always a great experience for any one who has cared about his classics in college. When I got to the Forum, I felt as if Caesar had been there yesterday.

The next year, 1889, I was serializing Rider Haggard's novel "Cleopatra" in the syndicate. Some years before this, when "King Solomon's Mines" was first published in England, Brander Matthews had told me to look up this new man, Haggard. Brander Matthews has always been a man of catholic taste, such as seldom goes with a critical ability of such a high order as his, and he has always kept abreast with and been in sympathy with new literary movements, however foreign they may be to his personal taste. He has always brought an unprejudiced attention to any new literary manifestation. And Haggard was the first to sound the new note in English fiction which was to make itself heard above everything else for years to come. (I do not count Stevenson here. He was a man apart; he belonged to no school.) Before Haggard came out with a new tune, we had only the old English novel, become mechanical and in its decline—the stories of Wilkie Collins, James Payn, Mrs. Braddon, Clark W. Russell. In contrast to these, "King Solomon's Mines" was a fresh breath from a new quarter of the world.

During my next visit to London in 1899 I went up into Scotland, to visit Andrew Lang at St. Andrew's. Andrew Lang was then literary adviser for Longmans, and while we were talking together he remarked that Longmans were about to bring out a new novel, " Micah Clarke," by a man named Conan Doyle, who had already published a shilling-shocker called "A Study in Scarlet." On the train, going down from Scotland, I bought the shilling-shocker at a news-stand, and as soon as I had read it decided to go after Doyle's stories for the syndicate. It used to be said of me in those days that all my geese were swans, because I went after things so hard.

I bought the first twelve Sherlock Holmes stories from Mr. Watt, Conan Doyle's agent, and paid £12 ($60) apiece for them. I had but one test for a story, and that was a wholly personal one—simply how much the story interested me. I always felt that I judged a story with my solar plexus rather than my brain; my only measure of it was the pull it exerted upon something inside of me. Of course, sometimes one is influenced by one's own mood; if one is feeling more than usually vigorous, he is apt to transfer some of his own high spirits to the story he is reading. To avoid being influenced thus, I always made a rule of reading a story three times within seven days, before I published it, to see whether my interest kept up. I have often been carried past my station on the elevated, going home at night, reading a story that I had read before within the same week.

When I began to syndicate the Sherlock Holmes stories, they were not at all popular with editors. The usual syndicate story ran about five thousand words, and these ran up to eight and nine thousand. We got a good many complaints from editors about their length, and it was not until nearly all of the first twelve of the Sherlock Holmes stories had been published, that the editors of the papers I served began to comment favorably upon the series and that the public began to take a keen interest.

Shortly after this I was in London, and one day when I was going somewhere in a cab with Wolcott Balestier, he told me that Doyle had just completed a new historical novel, "The White Company." I bought the American serial rights of the novel for $375; but when I sent the proofs of it around to the newspaper editors, they simply would have none of it. This, it must be remembered, was after the publication of the twelve Sherlock Holmes stories. I went to Mr. Laffan, of the New York Sun, and told him I had a novel of Doyle's I couldn't sell. Mr. Laffan took it off my hands and serialized it in the Sun.

This was one of the most interesting of all my trips to London. I was lunching one day with Sidney Colvin at the British Museum, where he was in residence as Curator of Prints and Engravings. Colvin told me about a new writer who seemed to have red blood in him, and who had done a good deal of work out in India that was beginning to be talked about in London. His name, Colvin said, was Rudyard Kipling. The name was so unusual that I had to write it down to remember it.

Shortly after this I paid my first visit to George Meredith. I went to Box Hill to see him about getting the right to syndicate several of his novelettes, such as "The Tale of Chloë," which had never been published in book form and were unknown in America. During the course of our conversation I said:

"Mr. Meredith, Mr. Colvin thinks very highly of a new writer named Rudyard Kipling. He believes he is the coming man. Do you know anything about him?"

"The coming man," said Meredith emphatically, "is James Matthew Barrie."

Neither Meredith nor Colvin was far wrong.

TO BE CONTINUED