One Way of Putting It.

AT last it is over, thank heaven. Thursday was a day of suppressed excitement. Every man you met looked as though he were going to be married the next hour—until the first telegrams came, and then some of them looked like they had recently been made widowers. Everyone talked about the fight, and everyone hung around the telegraph offices, everyone except the ministers and they kept the telephones redhot all day, firing in questions on the city editors. Nothing but a prize fight or a presidential election could have aroused such interest. If Gladstone and Bismarck had been having a joint debate in Jacksonville, no one would have waited for the telegrams. If all the great poets and painters in the world had assembled there to vie with each other in great creation, the milkman would not have driven a bit faster to get an evening paper. Young men of talent, the arts don't pay. If you want to be beloved by your countrymen, if you want to draw near to the hearts of the people, be cherished with their household gods, remembered in their prayers, if you want to be truly great, there are but two careers open to you—politics and the prize ring. It has been so ever since men were men. The old sports of Athens were much more interested in the victorious athlatai than the bards who meandered about with the laurels on their heads. People come to the state fair to see the horse racing, not to gaze upon Mrs. So-and-So's crayon work or silk crazy quilt.

The struggle of brawn with brawn seems to appeal more strongly than anything else to the great mass of the people, and it seems that all the primitive instincts have not died out of the world. Civilization is a very large boast. Like Eli Perkins , it has a greater reputation than it can live up to.

"A man's a man for all 'o that" and and will be for some years to come. Civilization has not destroyed the needs or passions of men's lives; the former it has only exaggerated and multiplied, the latter it has alternately whetted and drugged and drained into a thousand aimless, frivolous channels which nature knows naught of.

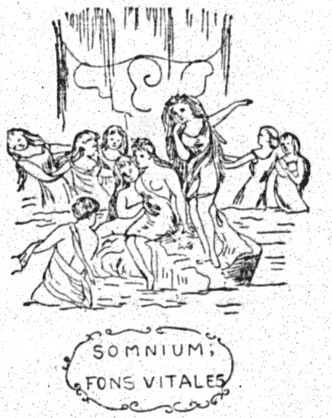

If it took

Ruskin

six months to interpret

Turner's

"Garden of the Hesperides,"

surely a person who is totally ignorant of

the technical laws of art may be allowed several weeks to struggle with the Lansing drop curtain. I have been suffering acutely from that curtain for two long years,

and sometimes I have longed for artistic knowledge, that I might understand and

appreciate

it better, but recently an artist told me that I was

enviable because of my ignorance, that art could not help one with that

curtain, for the more one knew of other pictures the less they knew of that. I

begin to believe his statement, for I have found art books as powerless to help

me with the anatomy as classical lexicons are to throw light upon that

abominable Latin. "Somnium Fons Vitales." I wonder how many people have been

able to translate it? Lincoln is full of colleges and ought to contain a good

deal of classical learning, but the lore of this generation has not got as far

as "Vitales." Most freshmen try to construe that Latin. The world looks very

bright to a freshman and he has the fond complacency to try anything from

discovering a new element to translating the

Iliad

in blank verse. He goes to

the theater saturated with

Horace

and he gazes on that mystic sentence and

tries to read it. When he fails he is chagrined. He swears that when he is a

senior he will translate those words. But when he is a senior he does not look

at it any more. By that time he has learned the lesson of his own littleness

and his own helplessness. He knows then that genius is something more than

eternal patience after all, and that even were he the proverbial patience on a

monument he would never write a

Hamlet

nor discover a new planet nor construe

the Latin of the Lansing drop curtain. He goes out into the world to live his

life and leaves the task to mightier men than he.

it better, but recently an artist told me that I was

enviable because of my ignorance, that art could not help one with that

curtain, for the more one knew of other pictures the less they knew of that. I

begin to believe his statement, for I have found art books as powerless to help

me with the anatomy as classical lexicons are to throw light upon that

abominable Latin. "Somnium Fons Vitales." I wonder how many people have been

able to translate it? Lincoln is full of colleges and ought to contain a good

deal of classical learning, but the lore of this generation has not got as far

as "Vitales." Most freshmen try to construe that Latin. The world looks very

bright to a freshman and he has the fond complacency to try anything from

discovering a new element to translating the

Iliad

in blank verse. He goes to

the theater saturated with

Horace

and he gazes on that mystic sentence and

tries to read it. When he fails he is chagrined. He swears that when he is a

senior he will translate those words. But when he is a senior he does not look

at it any more. By that time he has learned the lesson of his own littleness

and his own helplessness. He knows then that genius is something more than

eternal patience after all, and that even were he the proverbial patience on a

monument he would never write a

Hamlet

nor discover a new planet nor construe

the Latin of the Lansing drop curtain. He goes out into the world to live his

life and leaves the task to mightier men than he.

After all the sad, sad thing about that curtain is that it should be such a contrast to the rest of the house, which is really in very good taste. The drapings of the boxes, the color of the seats, the frescoing, the woodwork, are all very artistic and the harmony of colors is perfect. Very few theatres in the west can boast of such elegant interiors. It seems like those gauzy women in front had got in the wrong place some way. Perhaps, after all, there is method in the manager's madness, and the curtain is there to make us more keenly conscious of the artistic settings of the house itself. We should be sorry to interfere with any deep laid scheme like this, but aren't the managers bearing down a little hard on us? Wouldn't a fifteen minute exhibition of that curtain every night do? We would all promise to look and suffer and get it over with. Then they might cover it up in some way and let us enjoy ourselves for the rest of the evening.

No roof has ever served to shut out quite so

much aspiring egotism from the stars as the inoffensive one which

Mr. Stout

saw

fit to place upon the capitol building. It is a strange and amusing fact that

every one of the state officers and every one of their employes regard the

state house as their especial manor and place of abode. If you ask a

stenographer who works there, where his office is and what he does, his lips

may tell you various things, but his eyes always say, "The state house is my

office, and my business is running the state." The state house individual is

always carefully guarding state secrets which as a rule could be published to

the world without hurting anything—if they haven't been published already. He

is always finding out some dark political conspiracy which would turn the

wheels of civilization back a century or two if the vigilant state officer did

not expose it at the imminent risk of his re-election. The greatest part of his

time is taken up with keeping his honor clean. The state officer has a very

great opinion of his honor; no one admires it and respects it more than he. He

keeps it always by him and spends most of his leisure polishing it up. He is

most tiresome when he reaches the martyr stage, where he drags himself to work

when he is sick and burns the midnight gas—which the state furnishes. He then conceives

that he is there on a mission of mercy, that he is a philanthropist, not a

politician, and that he is doing it all for the good of his fellowmen. Now,

the truth is, my friend, you find it a fairly profitable martyrdom; you are not

there for your own health or your eternal brother, man; you are there for just

so many hundred

dred dollars a year, and just so many chances of political

preferment, and you know it. Of course you can be a martyr if you choose, but

you should at least be a merry martyr, for you get a fairly comfortable salary

out of it, besides all the wealth you are supposed to be laying up where moths

do not corrupt, neither thieves break in and steal.

dred dollars a year, and just so many chances of political

preferment, and you know it. Of course you can be a martyr if you choose, but

you should at least be a merry martyr, for you get a fairly comfortable salary

out of it, besides all the wealth you are supposed to be laying up where moths

do not corrupt, neither thieves break in and steal.

It is strange, but there seems to be something in the air of that state house which causes an inevitable enlargement of the head. The very janitor who mops the floor—sometimes he really does mop it—imagines that if he should lay off a day the reign of chaos and old night would begin immediately. There is a whole state house full of people, officers, clerks, stenographers and janitors, each of whom murmers daily to himself, "I am the state." The fact is, my friends, you are not the state, you are not even a very large part of it. You might all be impeached tonight and yet tomorrow the sun would rise upon the world just as it has done for some centuries. You might all be swept out into space, and still the street cars would run, the musee band play, and the town clock lose time steadily and strike in its usual erratic manner. You are just about as much a vital force in the state as the statue of Lincoln who airs himself continually on the court house tower. You are a figure-head, you stand for a great tradition.

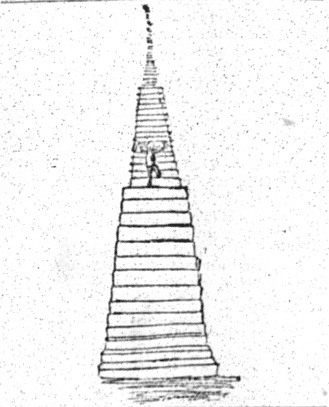

"Heaven is not reached by a single bound," no,

nor THE JOURNAL editorial rooms. You get there by means of stairs; a man might

write a new gradatum on those stairs. They are long and steep and narrow and

dark; some people say there is an end to them somewhere, but they are dauntless

climbers who have more courage and wind than the average explorer. It is

strange that mounting those stairs doesn't drive the editors to alcoholic

stimulants; it is hard to see how the normal strength of any man can hold out

farther than the first platform. If you have never been up there just recall

your first ascent of the capitol dome and multiply it indefinitely and you will

be somewhere near conceiving those stairs. Many a youth with his first sonnet

hugged close in his breast pocket has been found unconscious somewhere on the

way up. Oh, ye of youthful, blue-ribboned manuscript so carefully written on

both sides, great is glory but it is not worth that struggle. Do not chase fame

up THE JOURNAL stairs, there are more advantageous grounds in which to

pursue her. Long, long ere you reach the top you will decide that it is not

your vocation to be a litterateur, and probably before you reach the bottom

again your decision will be still more firm. The awful distance of the

editorial rooms from the ground has killed more ambition and saved the world

more bad poetry than we can ever know. One's aspirations may be high, but THE

JOURNAL stairs are higher. It is a long way up to the place where the poet

communes with the muses, and common mortals may not attain unto it. If the

"youth who bore 'mid snow and ice" had

been trained awhile on THE JOURNAL stairs, the Alps would never have fazed him, they

would not even have disturbed his composure.

been trained awhile on THE JOURNAL stairs, the Alps would never have fazed him, they

would not even have disturbed his composure.