McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 42 (December 1913): 33-48.

THREE

AMERICAN SINGERS

LOUISE HOMER

GERALDINE FARRAR

OLIVE FREMSTAD

THREE women are at this moment dominating the most critical audience and the most splendid operatic stage in the world— the Metropolitan Opera House of New York. One of these women came out of a new, crude country, fought her way against every kind of obstacle, and conquered by sheer power of will and character. One of them has lived a sort of fairy-tale of good fortune from the time she began to sing. Each one has achieved a supremely individual success. The careers of these three great singers make one of the most interesting stories in the history of American achievement.

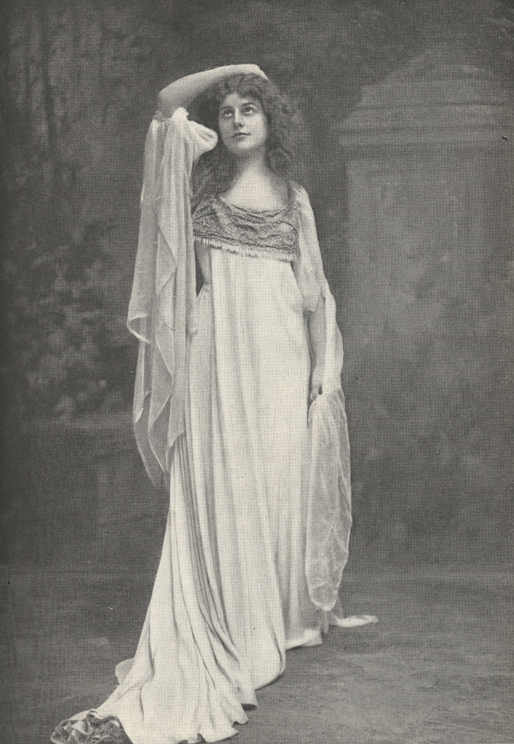

OLIVE FREMSTAD as Isolde

Copyright, Mishkin

OLIVE FREMSTAD as Isolde

Copyright, Mishkin

I

LOUISE HOMER

FOR thirteen years Mme. Louise Homer has been the principal contralto of the Opera

in New York. No other contralto has, on the whole, pleased the patrons of the Metropolitan Opera House so

well. Other contraltos have surpassed her in single rôles, but no one of them has sung so many parts so well or has maintained so high

an average. If she seldom rises above her standard of excellence, she almost never falls below it. Probably her physical poise has a

good deal to do with the evenness of her

LOUISE HOMER was a tall, handsome girl from Pittsburgh, with a big, unmanageable voice

and no definite ambitions, when she came to Boston and heard opera for the first time,

with Eames and the de Reszkes in the cast. Four years later she was singing with these

same artists. In Orpheus, perhaps the most beautiful music ever written for a contralto

voice, Mme. Homer made one of the greatest successes of her career

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

work. Her physical equipment is magnificent. Large, handsome, generous, she has reservoirs of strength and calmness to draw from.

Her freedom from vanity frees her from self-torture, and her nerves are hidden under

a smooth and strong exterior. She is blessed with an absolute integrity of health,

which enables her to meet the exigencies of her work vigorously and calmly. During

the entire opera season, when she is singing on the stage several times a week and

filling concert engagements as well, she manages her own house, her own nursery, and

her five children. Domesticity is not a rôle with Mme. Homer: it is her real self. Her children are splendid children,

and they are most fortunate in having a mother who meets the demands of a complicated

life so graciously, warmly, and simply.

LOUISE HOMER was a tall, handsome girl from Pittsburgh, with a big, unmanageable voice

and no definite ambitions, when she came to Boston and heard opera for the first time,

with Eames and the de Reszkes in the cast. Four years later she was singing with these

same artists. In Orpheus, perhaps the most beautiful music ever written for a contralto

voice, Mme. Homer made one of the greatest successes of her career

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

work. Her physical equipment is magnificent. Large, handsome, generous, she has reservoirs of strength and calmness to draw from.

Her freedom from vanity frees her from self-torture, and her nerves are hidden under

a smooth and strong exterior. She is blessed with an absolute integrity of health,

which enables her to meet the exigencies of her work vigorously and calmly. During

the entire opera season, when she is singing on the stage several times a week and

filling concert engagements as well, she manages her own house, her own nursery, and

her five children. Domesticity is not a rôle with Mme. Homer: it is her real self. Her children are splendid children,

and they are most fortunate in having a mother who meets the demands of a complicated

life so graciously, warmly, and simply.

Louise Homer was born in Pittsburgh, where her father was a Presbyterian minister. She grew up in a big, easy-going house where the children, when they were not at school, were always at the piano. She learned to sing easily and naturally, without any definite purpose or ambition. After the death of her father she went with her mother to Philadelphia, where she sang in a church. Up to that time she had had no regular instruction in singing, but the next winter she went to Boston to stay with her married sister and study voice under William Whitney and harmony under Sidney Homer. She had then a big, rich, unmanageable voice, and her teachers felt that something very fine could be made of it. In Boston Mme. Homer, then Miss Beatty, heard her first opera when Maurice Grau's company gave a season of opera at Mechanics' Hall. Sidney Homer got season tickets and took his pupil, who had then not the remotest idea of becoming an opera singer.

The first night, Emma Eames and the two de Reszkes were in the cast. Miss Beatty heard them with delight and amazement, with that sincere, whole-hearted pleasure of which she is still so capable, but without definite ambition. She was a tall, handsome girl from Pittsburgh, with generous impulses and becoming modesty, listening to an opera for the first time and forgetting herself. In less than four years she was singing in opera with those same artists, Emma Eames and the brothers de Reszke, at Covent Garden, London.

It was during that season of opera that Sidney Homer asked his pupil to marry him.

They

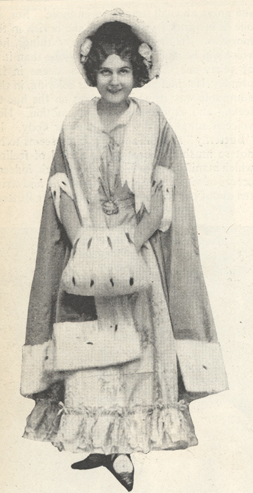

FARRAR'S STORY is the kind that Americans like: a story of success with a dazzling

element of luck. Miss Farrar is the only artist who could hold a baseball audience

through a performance of grand opera. There is something in her legend—in her personality,

her beauty and enthusiasm—that gets across to the American who is proverbially bored

by opera

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

were married very soon afterward, and he at once took his wife to Paris to study. They fitted up a comfortable apartment in the Trocadéro, and there Mme. Homer quietly and peacefully pursued her studies.

She was careful not to put any strain upon a naturally robust constitution. She enjoyed

life as she went along—her lessons, the people she met, the fine air, and the comforts

of her own apartment. She worked hard, but goading ambitions never kept her awake.

She was never harassed by nervous strain. She meant to go as far as she could, but

she had set for herself no goal that it would break her heart to lose.

FARRAR'S STORY is the kind that Americans like: a story of success with a dazzling

element of luck. Miss Farrar is the only artist who could hold a baseball audience

through a performance of grand opera. There is something in her legend—in her personality,

her beauty and enthusiasm—that gets across to the American who is proverbially bored

by opera

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

were married very soon afterward, and he at once took his wife to Paris to study. They fitted up a comfortable apartment in the Trocadéro, and there Mme. Homer quietly and peacefully pursued her studies.

She was careful not to put any strain upon a naturally robust constitution. She enjoyed

life as she went along—her lessons, the people she met, the fine air, and the comforts

of her own apartment. She worked hard, but goading ambitions never kept her awake.

She was never harassed by nervous strain. She meant to go as far as she could, but

she had set for herself no goal that it would break her heart to lose.

During her second winter in Paris, before she had studied operatic rôles at all, Mme. Homer sang for Maurice Grau, who advised her to study a number of rôles and make her début in opera as soon as possible. After consulting her teacher, Monsieur Koenig, she learned the grand aria from the fourth act of "The Prophet," which is a standard test aria for contraltos in France. A few weeks later she sang this aria at the Operatic Agency. The director of the Vichy Opera House happened to be in the next room while she was singing. When she finished the aria, he walked into the room where the artists on trial were assembled, and asked Mme. Homer whether she would accept an engagement with the Vichy Opera. She made her début in "Favorita" at Vichy, June 5, 1898. The summer season at Vichy is important because the audience is cultivated and cosmopolitan, made up of people from all the capitals of Europe. Mme. Homer's most conspicuous success was in "Samson and Delilah." From Vichy she went to Angers, where she sang through the winter season and was promptly engaged for Covent Garden. Since then her career has been one of uninterrupted success.

Histrionically and vocally, Mme. Homer's Amneris (in Verdi's "Aïda") is the most satisfactory ever heard in New York. No one else has sung that rôle here with such commanding dignity of presence, with such richness and power of tone. Her Brangäne, in "Tristan und Isolde," is one of the most beautiful and satisfying things she does. In this part she has certainly improved upon the German tradition. Her Brangäne is less wild and violent, more gentle and sympathetic, than that of the German contraltos who have sung the part here. Her warning cry from the tower is always one of the most beautiful moments in the whole opera. The mere amplitude of her voice is a pleasure. Its richness and power contribute to the volume and brilliancy of a performance. Several years ago, when Gluck's "Orpheus" was revived at the Metropolitan, Mme. Homer achieved the highest success of her career in the title rôle—perhaps the most beautiful music ever written for the contralto voice. Her noble rendering of that part will long be remembered in New York.

II

GERALDINE FARRAR

THE story of Geraldine Farrar's early youth is well known; it is the kind of story that Americans like. We admire success in which there is a large element of "luck," more than success laboriously won. We like a rich natural endowment, native "gift," fame in early youth. The mining-camp ideal obtains widely with us, and Miss Farrar's story is one that the ranchman or the miner can understand; it gratifies his national pride, meets his sense of the picturesque. When he puts a "Farrar record" into his phonograph, he has something of the feeling of part-ownership that our fathers had when they spoke of Mary Anderson as "our Mary."

Briefly, Miss Farrar was born in Melrose, Massachusetts, in 1882; went to Paris to study in 1897, when she was fifteen; made her début at the Royal Opera in Berlin as Marguerite when she was nineteen; and did not return to America until 1906, when she had already a European reputation behind her and was the avowed favorite of the Prussian capital.

Melrose, Massachusetts, is a dull little New England town, not far from Boston. Miss Farrar's father kept a small store there, but in the summer he was pitcher for the Philadelphia baseball team. He was a handsome man with a good tenor voice, and was still very young when his only child, Geraldine, was born. The mother, too, sang in her girlhood; but she was married at seventeen and her daughter was born before she was twenty. Miss Farrar's maternal great-grandfather was a blacksmith in Melrose, but her grandfather, Dennis Barnes, was a musician. There is no very glorious career for a musician in little New England towns, and Dennis Barnes was never esteemed a man of much force. He had a little orchestra which he taught and trained; he gave violin lessons; and he composed. He never made more than a scant living. He learned to play the violin from an Italian fiddler who lived in his back pasture.

Farrar a Darling of Fortune

Miss Farrar says she can not remember the time when she did not intend to become an opera singer. She never had any doubt about it, even before she had heard an opera. When she was twelve years old she heard Calvé as Carmen, in Boston. Then she was just as sure of her own career as she had been before. There are some photographs of Miss Farrar taken at about this time, in which she looks very much like the child elocutionist of the ice-cream social. The best thing that ever happened to Miss Farrar—and, in so far as luck goes, she has been the very darling of the gods—was that her parents had courage enough to borrow money and take her abroad to study early , before her self-confidence became too confident. Once she got to Paris, the finest thing in her, her capacity to admire, was aroused. Her photographs, taken after a year in Paris, look like another girl. Not that she was humbled. The peculiar note of her personality is that she has never been humbled, but quickened. In conversation Miss Farrar sometimes speaks of "the beauty that hurts," and those early Paris photographs show a face over which wave after wave of that kind of beauty had passed, marking it as with little knives.

There was never any one less afraid of violent emotions than Miss Farrar, or more gallant about accepting the depression that often follows pleasurable excitement. She consumes herself as ardently in her recreations as she does in her work; she gives herself out to the costumers who design for her, the artists who paint her, the stage-hands who adore her. For her own sake, one can but hope that she will train up a duller self to serve her for dull purposes. But she says that she "would rather live ten years thick than twenty thin." "Why should I want to string it out twenty, thirty years?" she exclaims. "I want to give it out all in a lump. I want to go hard while I'm at it!"

Miss Farrar's Views on Domesticity

Mr. Henry T. Finck, in his book, "Success in Music," prints some letters written to

him by Miss Farrar during her first year in Paris. They are a whirlwind of youth and

feeling. They are a much truer presentation of her than many of her published interviews,

because Mr. Finck has had the courage to let her be herself and speak for herself,

while friendly interviewers are prone to tone her down with platitudes, for fear that

she might be misunderstood. Miss Farrar is not a platitudinous person. She has a frankness

that is quite splendid and wholly ingratiating—the frankness of one who has nothing

to fear. She does not believe that conjugal and maternal duties are easily compatible

with artistic development; she does not believe that, for an artist,

WHEN GERALDINE FARRAR made her début as Juliet in New York seven years ago, some of

her critics were greatly disconcerted because she sang much of the chamber scene lying

down, in her night-gown. Her defense of this was as fiery as it was youthful. Incidentally

she murmured that not every prima donna could sing a scene lying down

Aimé Dupont

WHEN GERALDINE FARRAR made her début as Juliet in New York seven years ago, some of

her critics were greatly disconcerted because she sang much of the chamber scene lying

down, in her night-gown. Her defense of this was as fiery as it was youthful. Incidentally

she murmured that not every prima donna could sing a scene lying down

Aimé Dupont

COMING OUT of a new, crude country, without friends or encouragement, Olive Fremstad,

the great Scandinavian singer, has fought her way to the highest position that the

Metropolitan stage offers. The picture shows her on board a trans-Atlantic liner at

the close of the opera season

anything can be very real or very important except art. She quotes with fervor that

there is nothing in the world so ugly that it can not be made beautiful in art; and

that there is nothing in the world so beautiful that it can not be made banal by a

stupid or prudish artist.

COMING OUT of a new, crude country, without friends or encouragement, Olive Fremstad,

the great Scandinavian singer, has fought her way to the highest position that the

Metropolitan stage offers. The picture shows her on board a trans-Atlantic liner at

the close of the opera season

anything can be very real or very important except art. She quotes with fervor that

there is nothing in the world so ugly that it can not be made beautiful in art; and

that there is nothing in the world so beautiful that it can not be made banal by a

stupid or prudish artist.

Learned Much from Bernhardt

Miss Farrar admits frankly that she was always an indifferent student. She would work only at what interested her. Teachers told her that she must sing in a church choir, and then in concert, before she could sing in opera. She smiled and went her way. She undertook a course of training under a teacher of plastic art in Paris, and, after a few lessons, paid her tuition and gave it up. She could learn nothing from practising Delsarte before a mirror. She learned from life, and people, and the theater—a great deal from Mme. Bernhardt, who warmly admired the girl's beauty and talent.

Miss Farrar was not always easy to please in the matter of teachers, but she managed to get on famously with the most exacting teacher in the world, Lilli Lehmann. In Miss Farrar's study on 74th Street West, there is a veritable exhibit of photographs and engravings of Lehmann, in the heroic pose of song and in the ample dignity of private life; each covered with paragraphs of painstaking German script, recording with mathematical exactness the degrees of her belief in and admiration for her pupil. Certainly, if the youthful Geraldine played fast and loose with other teachers, she worked seriously with Lehmann. That powerful repository of tradition bestirred herself, as she always does when she finds the stuff out of which artists are made. She began by resolutely tying Geraldine's hands behind her—this not in a figurative sense, but with a stout cord. She said Miss Farrar threw her hands about too much, and that she must say what she had to say with her face.

It was Lehmann who was first able to make the world believe—and her pupils understand—that it is the quality of a voice, not the quantity, that matters. She prizes the individual quality of a beautiful voice more than any feats of skill it can be made to accomplish. From her Miss Farrar learned to treat her voice with consideration, with courtesy. "An instrument," she says, "is made to be played upon intelligently, not knocked to pieces."

Farrar Defends Her Unconventional Juliet

Miss Farrar says that the emotional element of her parts often interests her more than the purely lyrical aspect. Some of her teachers used to prophesy that she would break training, run away, and become an actress. When she made her début as Juliet in New York seven years ago, her critics were greatly disconcerted because she sang much of the chamber scene lying down, in her night-gown. Her defense of this was as fiery as it was youthful. Incidentally, she murmured that not every prima donna could sing a scene lying down—and every one had to admit that that was true. Miss Farrar says:

"People are often shocked because when I sing in concert I don't wear gloves. I can't sing in gloves. I can't sing if I feel my clothes. I don't wear stays, and I would like to sing without any clothes, if I could. Fifty years ago a singer had nothing to do but nourish herself and sing; they had never discovered their bodies. But with a singing actress it's different; I sing with my body, and the freer it is, the better I can sing."

It is as a singing actress, indeed, that Miss Farrar should be heard and enjoyed. Rôles like Violetta in Verdi's "Traviata," Marguerite in Gounod's "Faust," and Gounod's Juliet, which were formerly vehicles for the execution of a singer, opportunities for coloratura, Miss Farrar sings in a modern way, as characters or impersonations. She takes her cue from the dramatic import of the aria rather than from its vocal possibilities, and she may be half-way through a lyrical passage before one recognizes that it is one of the so-called "big arias," which formerly always brought the singer to the front of the stage and drew out her voice to its fullest power. The waltz-song in "Romeo and Juliet," for instance, Farrar sings lightly, carelessly, girlishly. The jewel song in " Faust" she sings with a lightness and gleefulness against tradition.

During her first season in New York Miss Farrar achieved the feat of presenting a wholly fresh Marguerite. She sang the part as if it had never been sung before, played the character as if Goethe's "Faust" had just been written, and his Gretchen not dulled and formalized by having been marked off in lessons for college classes. Much of her stage business was entirely her own; it was always spontaneous and impulsive. Her singing of the "He loves me, he loves me not," when Gretchen pulls the flower to pieces, was a marvel of youth and feeling expressed in sound. Her performance was full of moments of reality, like that moment when Faust, having overheard her song to the flower, rushes back with the assurance of conquest, and she weakly, despairingly, half closes the window against him.

Miss Farrar is apt to sing a new part with too much action, or, at least, too much

"business." As time goes on she usually simplifies, and as she grows she will simplify

even more. For, as one of her critics wrote of her, she is rich in tomorrows. In the

natural course of things, her voice will be much better at forty-one than it is at

thirty-one; it is now by no means in its prime. Its chief beauty is in its coloring,

in the admirable way in which it takes on the hue of feeling and expresses shades

of emotion. Her voice is supple and elastic, like her body. In "Butterfly" and "Manon"

it often seems to be not so much vocalization as a kind of feeling which manifests

itself in sound—which, indeed, occurs in sound. Much has been said and written about the remarkable fidelity of her Butter-

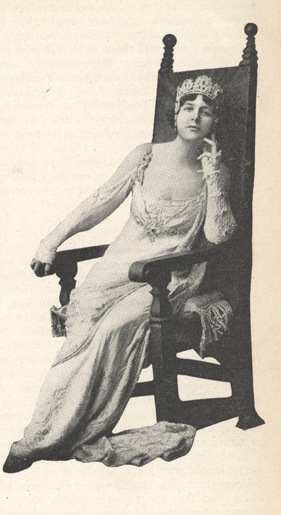

THE COMMON SAYING is that Mme. Fremstad was a contralto who by persistent effort has

extended her range and become a soprano. She herself says "the Swedish voice is always

long." Her first appearances in soprano rôles were met with bitter hostility by the

critics, who declared her "a warning to ambitious contraltos." Six years later she

was singing all the great soprano parts of Wagnerian opera. The picture shows her

as Sieglinde

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

THE COMMON SAYING is that Mme. Fremstad was a contralto who by persistent effort has

extended her range and become a soprano. She herself says "the Swedish voice is always

long." Her first appearances in soprano rôles were met with bitter hostility by the

critics, who declared her "a warning to ambitious contraltos." Six years later she

was singing all the great soprano parts of Wagnerian opera. The picture shows her

as Sieglinde

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

MISS FARRAR says she can not remember when she did not intend to become an opera singer.

She was fifteen when her parents took her to Paris to study. The picture shows her

as Mimi in Puccini's "La Bohême"

Copyright, Aime Dupont

fly, so Japanese in appearance, in posture and movement, that it has been marveled

at not only by Americans who know Japanese life, but by the Japanese themselves. Her

Manon (in Massenet's opera), without the emphasis of exotic costume and attitude,

is equally well realized and even more delicate. Such archness and irresponsibility

are the outcome of many fine things—of a quick and volatile fancy, a well nourished

imagination, and of an impulsive and tender sympathy with human life.

MISS FARRAR says she can not remember when she did not intend to become an opera singer.

She was fifteen when her parents took her to Paris to study. The picture shows her

as Mimi in Puccini's "La Bohême"

Copyright, Aime Dupont

fly, so Japanese in appearance, in posture and movement, that it has been marveled

at not only by Americans who know Japanese life, but by the Japanese themselves. Her

Manon (in Massenet's opera), without the emphasis of exotic costume and attitude,

is equally well realized and even more delicate. Such archness and irresponsibility

are the outcome of many fine things—of a quick and volatile fancy, a well nourished

imagination, and of an impulsive and tender sympathy with human life.

Like her impersonation of Dumas' Lady of the Camellias in "Traviata," her Manon is fickle, wilful, wayward, as beautiful and as elegant as a Watteau figure or a femme galante by Fragonard. In the first act, as the little country girl on her first journey, this Manon is indescribably fresh and sweet; through scene after scene, to follow the pretty thing is to pardon her. No one who has once heard it can ever forget that last scene, when the dying Manon, in rags, and on the way to Havre for deportation, lying by the roadside, looks up at the evening star and says to her lover, with an arch little flicker of the old lightness: "Ah, the lovely diamond! You see, I am still coquette!"

Farrar's Beauty has been Held Against Her

Miss Farrar says humorously that when she returned to her own country to sing with the Metropolitan Opera Company, she expected that her youth and immaturity would be taken for granted; but instead only the things she did well were taken for granted. Unquestionably, her youth, her foreign triumphs, and her beauty were held a little against her. There was a feeling among the more critical members of her audience that she herself overrated the worth of these assets, and that she depended too much upon their carrying power. That was not strictly true. She no doubt enjoys being young and beautiful. But, in so far as her work at the Opera goes, her idea has been to sing her parts as she felt them and understood them, with the feeling and conviction of youth, even the effervescence of youth, and to mature and deepen them as she matured and hardened. The event has proved that she was right. Her frankness and her fearlessness amount to artistic rectitude. Often, in defending a conception, she says more than she means, perhaps; but she is not afraid to say what she feels at the moment. One thing that all people of really first-rate ability have in common is an absence of caution; they are not afraid to say to-day what may be quoted against them to-morrow.

Miss Farrar is not so much fortunate in being beautiful as she is fortunate in her peculiar kind of beauty. We have had beautiful American singers before, but their faces have been of a solidity! Even so lovely a woman as Emma Eames—after one had seen her unchanging countenance as princess and peasant and Egyption slave, through grief and joy and love and hate—used to inspire one with the wish that she might have another face for a while, even if it were a less beautiful one. Miss Farrar's face is an anomaly; it has the flexibleness that is so seldom found with regular features, the beautiful pallor rare in American women, a finely shaped forehead, and splendid, changing eyes, full of storm and color, of that strong sea-gray color that has always been most effective on the stage, where it becomes the mirror of emotion.

WHEN FARRAR began to study "Tosca," Mme. Bernhardt, who warmly admired the girl's

beauty and talent, gave a special performance of the play for her benefit. In " Tosca,"

as in all her parts, Farrar is, above all, a singing actress

WHEN FARRAR began to study "Tosca," Mme. Bernhardt, who warmly admired the girl's

beauty and talent, gave a special performance of the play for her benefit. In " Tosca,"

as in all her parts, Farrar is, above all, a singing actress

Her youth and its effervescence—has been a source of delight to many thousands of people—her sternest critics will miss it when it has passed. One often feels, in listening to her, that she finds the Opera a splendid game, in which not only she and the tenor and the orchestra, but the whole audience, take part; that she is enjoying every moment of it, and making things come her way every moment.

Farrar and the "Average American"

From her childhood the national game, baseball, has been curiously associated with Miss Farrar's name, and this association is not so incongruous as it may seem. She has a hold on the baseball type of American. She is the only artist—and she is always an artist—one can think of who might be able to hold through a performance the howling throngs that crowd the league ball-grounds in Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Chicago, New York—and this not by singing "The Last Rose of Summer" or "The Suwanee River," as earlier prime donne used to do. She would play her own game in her own way, but there is something in her legend, in her personality, in her beauty and enthusiasm, that gets across to the American who is proverbially bored by the art in which she excels. I doubt whether Miss Farrar would be flattered by this. Like all young artists, especially those who have not had an artistic background, she is jealous of art for its own sake. But she must at least be pleased that the phonograph companies find it necessary to issue a new Farrar record every month, and this necessity comes about only because Miss Farrar has made herself heard even above the roar of the ball-park.

The star dressing-rooms at the Metropolitan Opera House are large and comfortable, but they look a good deal like the fitting-rooms of a good dressmaking establishment—all except Miss Farrar's, which is just such a luxurious bower as, when we were fifteen, we all imagined a singer's dressing-room must be. She enjoys all the parts she plays, and among them the rôle of prima donna ("prima donna assoluta," as one of Colonel Mapleson's stars insisted upon being billed!), and she is by no means wanting in the wit to be amused at her own enjoyment.

Farrar Says She Wants to Keep a Few Feelings for Her Own Use

As a singing actress Miss Farrar is a much greater person than many of her blind admirers ever realize. There is not an indolent nerve in her lithe body. She constantly grows in her parts. She works to satisfy some restlessness within herself. Ten years from now the result of all this will be the more apparent. When the air is cleared of both incense and cavil, when her youth and beauty no longer dazzle the susceptible nor prejudice the perverse, then, in the ripeness of her powers, we shall be able to take her full measure.

Miss Farrar declares frankly that she loves the sensuous rather than the intellectual side of her work; that music is a short cut to emotion. She is, as she says, Latin in her sympathies; she loves warmth and color, the excitement that attends a stimulated imagination, the releasing of these things in her voice and face. The fact that many of the world's greatest singers, and her own teacher, Lilli Lehmann, were intellectual singers, does not tempt her to take an attitude or to deceive herself. She is as frank with herself as she is with her public. She confines herself to the work that she can do with delight, with youth, with joy. She says emphatically that she does not wish to forget herself to marble. "Some of us," she remarks, "want to retain a few of our feelings for household ornaments." In a letter written to Mr. Finck in 1909—quoted by him in his book—Miss Farrar says: "I have learned that talents have limitations. . . . I do not long to, nor do I believe I can, climb frozen heights like the great Lehmann."

III

OLIVE FREMSTAD

THE singer who is now aspiring to and attaining those frozen heights of which Miss Farrar speaks, is Mme. Olive Fremstad. From the night of November 25, 1903, when Fremstad made her début here, and the night of December 2, 1904, when she electrified her audience by her Kundry in "Parsifal," all students of the opera realized that here was a great and highly individual talent, unlike any that had gone before it. From that time on we have watched the rise of this great artist, have seen the fruition of years of unfriended labor, the rapid crystallization of ideas as definite, as significant, as profound as Wagner's own.

Mme. Fremstad says: "We are born alone, we make our way alone, we die alone." She believes that the artist's quest is pursued alone, and that the highest rewards are, for the most part, enjoyed alone. She is not confident that much of a singer's best work ever crosses the footlights to the people who sit beyond. She says: "My work is only for serious people. If you ever really find anything in art, it is so subtle and so beautiful that—well, you need never be afraid any one will take it away from you, for the chances are nobody will ever know you've got it."

Fremstad's Mysterious Personality

It was Mme. Fremstad's Kundry that first made her known throughout this country, and a little of the mystery of that mysterious wild-woman has always clung to her. No singer except Ternina has managed to live in such retirement here, so to lose herself in New York. To her fellow singers she is almost unknown. Members of the Metropolitan company are often heard to exclaim that they "haven't the least idea what the Fremstad really looks like." She seldom goes to the opera except to sing. She gets very little from people; she does not catch ideas or suggestions from what she sees or hears; everything comes from within herself. Work is the only thing that interests her. She says she has tried this and that thing in the world which, from a distance, seemed beautiful; but that art is the only thing that remains beautiful.

Mme. Fremstad is the most interesting kind of American. As Roosevelt once said, Americanism is not a condition of birth, but a condition of spirit. She was born in Stockholm, Sweden; her mother was a Swede, her father a Norwegian. Her parents, her grandparents, and her own older sisters sang. Mme. Fremstad can not remember a time when she could not read music. She began to study piano at the age of four. She first sang in public when she was four years old, at a church social in Christiania, Norway. She sang standing on a table, and after she was lifted down she was given a chocolate horse. She supposed that this was to be eaten, but when she bit off the tail she was shaken and put in a corner. Mme. Fremstad says that she can remember exactly what she thought and felt in the corner, and that she has not since been a stranger to those emotions. More than once, after a great effort at the Opera, she has remembered the corner.

As a Child Fremstad Led the Singing at Revivals

When she was six years old, Olive Fremstad came with her family to America. Her father settled in St. Peter, Minnesota, where he practised medicine and preached. During their first years in Minnesota, Dr. Fremstad sometimes conducted revivals. He took his daughter Olive with him from settlement to settlement, to play the organ and to lead the singing. They had a little portable organ which they took about with them. Still under ten years of age, Fremstad could not reach the organ pedals, so her father made wooden clogs which he tied to her feet, piecing her out to meet her task. There are people in Minnesota who still remember the fire with which the tow-headed child used to attack the organ when, at a signal from her father, she started the hymns of penitence and entreaties for pardon. In revivals, a great deal depends upon the emotional resources of the song-leader, and Dr. Fremstad found these qualities in his daughter. Her voice was effective; it aroused the sinner, awoke remorse and longing.

There is a legend in some parts of Minnesota that the child herself was more than

once "converted"; that, when the congregation was slow

THE OPERA-GLASS will never betray any of Mme. Fremstad's secrets. The real machinery

is all behind her brows. When she sings Isolde, no one can say by what means she communicates

the conception. A great tragic actress, her portrayal of a character is always austere,

marked by a very parsimony of elaboration and gesture

Copyright, Mishkin

to kindle, the child at the organ would be overcome by emotion. The result was invariable: repentant sinners rose from every corner of

the house. I have refrained from questioning Mme. Fremstad about this story; on this

point the memories of the Minnesota settlers may be better than her own. However,

when I said something to her about the completeness of her penitent Kundry in the

last act of "Parsifal,"—the way in which her presence dominates the stage, though

she is given but two words to speak, "Dienen, dienen!"—she remarked, with a shrug: " It ought to mean something. There is much of my childhood

in that last act. You have been to revivals? Well, so have I."

THE OPERA-GLASS will never betray any of Mme. Fremstad's secrets. The real machinery

is all behind her brows. When she sings Isolde, no one can say by what means she communicates

the conception. A great tragic actress, her portrayal of a character is always austere,

marked by a very parsimony of elaboration and gesture

Copyright, Mishkin

to kindle, the child at the organ would be overcome by emotion. The result was invariable: repentant sinners rose from every corner of

the house. I have refrained from questioning Mme. Fremstad about this story; on this

point the memories of the Minnesota settlers may be better than her own. However,

when I said something to her about the completeness of her penitent Kundry in the

last act of "Parsifal,"—the way in which her presence dominates the stage, though

she is given but two words to speak, "Dienen, dienen!"—she remarked, with a shrug: " It ought to mean something. There is much of my childhood

in that last act. You have been to revivals? Well, so have I."

All this was not bad training for a dramatic soprano, certainly, and very different from the church-concert exercises in which children are put up to show off. From the beginning, Mme. Fremstad had to get results with her voice.

Her Father's Relentless Discipline

It was for the piano, however, that her father intended her. In Sweden and after they came to Minnesota, he was relentless about her practising. She spent hours every day at the piano. Her wrists still show the mark of early strain. After each music lesson she had to take home a report from her teacher, stating how well she had known her exercises. If the report was not satisfactory, her father punished her—not by argumentative methods. Dr. Fremstad's easy-going American neighbors thought his severity outrageous; they thought the child ought to be taken away from a father who made her work so hard. Mme. Fremstad says: "To know how to work is the most valuable thing in the world, and there are very few people indeed who know what real work is. Many a night, before I go to sleep, I thank my father in my mind that he taught me."

When she was twelve years old Mme. Fremstad began to give piano lessons. Her father thought she would study still more earnestly if she instructed others, and that she ought "to be bringing in something." Some of her pupils were older than their teacher, who had had so little time for play and so few playthings that she sometimes gave extra lessons in exchange for a doll.

The Solitary Beginning of Fremstad's Career

When her parents moved to Minneapolis, Olive Fremstad began to sing in a church choir in that city. In the winter of 1890, when she was eighteen years old, she held a good church position in Minneapolis. She got a leave of absence for the Christmas vacation, and came on to New York, without telling any one where she was going. She had no particular reason for concealing her purpose, but it was not her habit, even then, to take many people into her confidence. She arrived in Jersey City on Christmas eve, and came across the ferry alone. She did not, of course, know any one in New York. It would be interesting to conjecture what she thought about when she first crossed the North River on that Christmas eve of 1890—whether she had any forebodings that the dark city before her was to be, in a manner, her antagonist, the scene of her fiercest struggle and greatest conquests. But what she thought one would never find out from Mme. Fremstad. She is not a sentimental person. She has not been back to Scandinavia since she left it a child of six, simply because her business has never called her there. She says romantic people never get anywhere.

The day after Christmas, Miss Fremstad found a teacher who tried her voice. She told him that she was a poor girl, that she had no money and would have to earn her way while she studied; under those circumstances, would he advise her to stay in New York? He advised her to stay. She gave up her position in Minneapolis and remained in New York. She sang in St. Patrick's Cathedral, and in 1891 made a concert tour with Seidl. In three years she had saved enough money to go to Germany to study. Although the opera was going full blast in those days, and the "Ring des Nibelungen" was new upon the Metropolitan stage in the years when Fremstad was studying in New York, it is my impression that she was never present at an operatic performance at the Metropolitan Opera House until she came back from Germany to sing there.

A Worker, Not a Dreamer

When I asked her how it happened that she did not go to the opera, she replied that she "had to save her money." Fremstad never squandered her brains in dreaming about the future. She says she never looked further than a step ahead; that she could not divide her energy up into near and remote purposes; she had to have all her mind to do the next thing as well as possible. She insists that she worked as intensely and devotedly at her church singing as she does at her operatic rôles.

Mme. Fremstad made her début in opera at Munich, where she sang for ten years, with results more satisfying to her public than to herself. The Munich public liked her in com- edy. The verdict there was that she was a singer of unusual talent, with a light, pleasing voice. She sang mainly contralto and mezzo-soprano parts, especially parts like Amneris, in which the singer must be able to invade soprano territory. This was disheartening work at last, because Mme. Fremstad felt that the upper tones of her voice were not being developed.

The common saying is that Mme. Fremstad was a contralto who by persistent effort has extended her range and become a soprano. She herself says: "The Swedish voice is always long." Nilsson and Jenny Lind had this same extended range. When Mme. Fremstad returned to New York ten years ago, her contralto tones were unquestionably more beautiful than her upper notes; they were richer, more beautifully colored, had a more individual quality. She herself believed that her upper voice would have an equally distinctive quality if she had the same opportunity to develop it. In this belief she was almost alone.

Singing masters and critics have always been hostile to a singer's efforts to extend her scale. It was constantly charged against Viardot that she had somewhat injured her entire voice for the acquisition of a few tones above her natural compass. It has always been with singers of the greatest talent, moreover, that the voice has been most difficult of subjugation. It would seem that when the voice becomes the vehicle of the mind, made to serve for some end beyond its own sensuous beauty, it has to be reconquered on a higher plane. The more subtle the intelligence, the more individual the quality of the voice, the more reluctant and unaccommodating is the organ itself.

Jenny Lind's voice required extraordinary labors on the part of the singer, and remained uneven to the end of her career, the middle tones being always slightly veiled. Pasta's voice was originally weak and husky, inflexible—as mere

sound, quite without charm. Chorley wrote of Viardot that from the first her hearers recognized that in her voice "nature had given her a rebel to subdue, not a vassal to command." It has seldom happened that a voice easily managed, rich, sweet, even throughout

DURING the entire opera season, when she is singing on the stage several times a week

and filling concert engagements as well, Mme. Homer manages her own house, her own

nursery, and her five children. She is never harassed by nervous strain. Her singing

is the expression of a rich, well poised nature that has never tortured itself with

goading ambitions

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

its compass, has fallen to the lot of a singer of the highest talent.

DURING the entire opera season, when she is singing on the stage several times a week

and filling concert engagements as well, Mme. Homer manages her own house, her own

nursery, and her five children. She is never harassed by nervous strain. Her singing

is the expression of a rich, well poised nature that has never tortured itself with

goading ambitions

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

its compass, has fallen to the lot of a singer of the highest talent.

Fiercely Attacked on Her Début as a Soprano

Although Mme. Fremstad's Kundry was an almost sensational success, critics complained that the music of the second act lay beyond the natural compass of her voice. It was not until December 13, 1905, that she at last made her début in a soprano part, the Brünhilde in "Siegfried." Of this performance the critic of the New York Sun wrote: About 11.15 P. M. on Wednesday, Olive Fremstad awoke from the dream that she was a dramatic soprano. . . . The high notes which do not belong to her scale, for which she had made such elaborate preparation, refused to come. They were pitiful little head tones; . . . the meaning of Wagner was lost; . . . the final duet was a saddening exhibition. . . . This experiment should be a warning to ambitious contraltos, etc.

Six years later the same critic wrote of her Isolde: Mme. Fremstad as Isolde took the opera into her hands as soon as the first act was fairly started. Her Isolde last night rose to new heights, and it must be said with all possible emphasis that this was due to increased mastery of her tones. She has never before sung with such freedom, such assurance, such boldness of attack, such a marvelous variety of color, and such perfectly carrying tone. Having this splendid vocal equipment at her command, she threw herself into the rôle with such an outpouring of dramatic eloquence that she fairly lifted her associates above themselves.

This "splendid vocal equipment" the singer has built tone by tone, without much encouragement from her critics. Mme. Fremstad says: "I do not claim this or that for my voice. I do not sing contralto or soprano. I sing Isolde. What voice is necessary for the part I undertake, I will produce."

Fremstad a Great Tragic Actress

The Wagnerian rôles, of course, offer the creative singer great opportunities. Wagner said he discovered that a good libretto could not be a great poem; that a libretto must retain the simplicity of legend, that the characters must be indicated rather than actualized. It is in the musical ideas and in the scoring of them that the poem flowers, that the legend rises from the low relief of archaic simplicity and becomes present and passionate and personal. Mme. Fremstad has developed these heroic rôles in the heroic spirit. A great tragic actress, she is, of course, able to give these Wagnerian heroines color and passion and personality and immediateness. An actress with such power to create life and personality might well forget the great ideas which lie behind these women, in realizing and releasing their rich humanity. But with Mme. Fremstad one feels that the idea is always more living than the emotion; perhaps it would be nearer the truth to say that the idea is so intensely experienced that it becomes emotion.

However definite and full her conception of a character, her portrayal of it is always austere, marked by a very parsimony of elaboration and gesture. After you have heard her sing Isolde, for instance, you are unable to say by what means she communicated to you the conception that is all too-present with you. You can not recall any carefully contrived stage business by which she took advantage of the composer. You can not say, "By such and such a thing she accomplished so and so." You are driven back to the conclusion that whatever happened during the performance, happened in Mme. Fremstad; that the fateful drama actually went on behind her brow.

Mme. Fremstad's impersonations are deeply conceived rather than highly inflected. She rejects a hundred means of expression for every one that she uses, but the means she finally adopts is often a hundred things in one; it has its roots deep in human nature, it follows the old paths of human yearning, it repeats those habits of mind and body which, by repeating themselves, define human nature. But her means of expressing these things are so simple that, powerfully as they affect us, we are scarcely conscious of the means themselves; we get the feeling, but we do not know how we get it. Why does one so vividly remember her oath upon Hagen's spear in the third act of "Götterdämmerung"? Other singers have caught the spear as fiercely and have sung the passage with as much righteous indignation; but, at some time or other in her study of the part, Mme. Fremstad has been able to realize Brünhilde at that moment more intensely than other singers have done. Artistic experiences are always mental experiences, and the instrument of one's art never forgets a great moment—can always reproduce it.

Kundry—Fremstad's First Great Success

A great artist usually handles a difficult situation simply, but that simplicity has cost the imagination many births and deaths; it is the very flower of all the artist's powers. Take, for instance, the moment in which Kundry gives the young Parsifal his ersten Kuss in Klingsor's garden. The enchantress is bound by tradition to give this kiss while she is seated on a couch, upon which she has been wheeled into the middle of the stage. Parsifal, perforce, must kneel beside her in order to be kissed at all. The duration of this kiss, under the full glare of the calcium light, is determined by the orchestra; it must last through a long orchestral passage. Parsifal must start back from it and be re-subdued to it before he finally breaks away with the cry, "Amfortas! die Wunde!" How is the singer to manage the mere element of duration without making the caress either formal or ridiculous? Kundry bends over the youth to give him this kiss with perfect self-confidence, almost indifference; she has never failed to vanquish her knight. But, as her face comes near to his, her indolence changes into something less negative; she is moved by a sort of tenderness, powerful because it is corporeal and sincere. Her right arm is about the boy; with her left hand she lifts her flowing hair and holds it before her face and his, like a scarf. Behind this she kisses him. The inclination of her head, every line of her body, contribute to the poetry of the moment. In Mme. Fremstad's performance of the part this is always a great moment;—it might so easily be a great stupidity.

Wagner had done many kinds of women before he did Kundry, and into her he put them all. She is a summary of the history of womankind. He sees in her an instrument of temptation, of salvation, and of service; but always an instrument, a thing driven and employed. Like Euripides, he saw her as a disturber of equilibrium, whether on the side of good or evil, an emotional force that continually deflects reason, weary of her activities, yet kept within her orbit by her own nature and the nature of men. She can not possibly be at peace with herself. Mme. Fremstad preserves the integrity of the character through all its changes. In the last act, when Kundry washes Parsifal's feet and dries them with her hair, she is the same driven creature, dragging her long past behind her, an instrument made for purposes eternally contradictory. She had served the Grail fiercely and Klingsor fiercely, but underneath there was weariness of seducing and comforting—the desire not to be. Mme. Fremstad's Kundry is no exalted penitent, who has visions and ecstasies. Renunciation is not fraught with deep joys for her; it is merely—necessary, and better than some things she has known; above all, better than struggle. Who can say what memories of Klingsor's garden are left in the renunciatory hands that wash Parsifal's feet?

After her ministrations to the knight, she goes to the rear of the stage and stands with her back to the audience, but there is no doubt as to what she is doing. She is not praying or looking into herself: she is looking off at the mountains and the springtime. From the audience one seems to see the ranges of the Pyrenees, to feel suddenly and sharply the beauty of the physical world. She moves toward the door with her bent step of "service." Before she disappears she turns again and looks at Parsifal. There are many degrees of resignation, it seems; the human spirit can be broken many times before it becomes insensate. Then only does she in truth renounce.

In the last scene renunciation is complete and the will to live entirely gone. This scene Mme. Fremstad continually improves. One used to feel her entrance too much, there was too much of the fixed religious idea in it. Now she effaces herself among the crowd of knights. Her personality was conflict. The struggle over, she is without personality; there is nothing of her but a desire for release. When the Grail is extended to her, she sinks slowly, and against the altar stair lie her dead hands, which have at last renounced—everything. Nothing short of death itself could make an absolutely sure convert of Kundry. There were many such stubborn struggles in the early days of the Church; they are to be found even in the lives of the saints.

Fremstad's Power of Transformation

Like Geraldine Farrar, Mme. Fremstad costumes her parts herself. She not only designs her costumes—she practically makes them. Many of her most effective ones are not garments at all, but pieces of fabric which she drapes and pins together before she goes upon the stage, giving them exactly the lines she desires. Thus her costumes become a part of the action. Her body she is able to manage and readjust very much as she does her fabrics. It is difficult to believe that her voluptuous Venus and her girlish Brünhilde are made out of the same body. How, for instance, when she sings Giulietta, in "Tales of Hoffmann," does she remold her own strongly modeled countenance into the empty, sumptuous face of the Venetian beauty?—lifted, one might say, from a Veronese fresco.

This girlish Brünhilde, in "Die Walküre," is a wholly original conception. The traditional Brünhilde is a large, full-figured woman, oppressively mature, who stands upon a rock and sings; she moves as little as possible, and then with matronly dignity. Mme. Fremstad's idea is that the war-maiden in the first opera of the Ring is a girl, not a matron. During her magic sleep on the rock she, if she does not grow older, at least loses her girlishness, so that Siegfried finds her a young woman. It is not until she appears in "Götterdämmerung" that Mme. Fremstad permits her Brünhilde that full-blownness which usually stamps the Valkyr throughout the Ring. This conception is justified by the score; the Valkyr music is restless, turbulent, energetic. The Valkyrs' ride is the music of a pack of wild young things. Motion—lightness of foot, spring of step, eagerness of body—is the physical expression of Mme. Fremstad's Brünhilde. The short skirt—a courageous innovation—no doubt contributes to the effect of slender girlishness. But the matter is accomplished by means more subtle.

The short skirt would be a pathetic impropriety in a statuesque Brünhilde; the accent is in the nervous foot and leg, the knee usually a little bent, as if she were always ready to run. Her shoulders, too, incline forward with a sort of youthful eagerness, like the shoulders of a boy running. Her body looks straight and athletic, like a boy's. But everything goes back to the untamed energy, the rhythm of the Valkyr music. The Valkyr's first song she does not, certainly, sing as well as other Brünhildes have sung it; but after the first few moments the magnificently vital conception never flags. Impulsive youth explains much in Brünhilde that seems inexplicable in a mature and discreet Valkyr; her gibes at Fricka, her passionate hero-worship, her feeling that people matter more than laws. Wotan's reproaches are less revolting than when they are directed toward a mature woman. The Valkyr is a girl being sacrificed, not a woman being degraded.

Any one who watches Mme. Fremstad's work is driven to the conclusion that, although she gives such distinctly different physical personalities to her Sieglinde, Elsa, Kundry, Tosca, her make-up box has little to do with her transformations. The opera-glass will never betray any of Mme. Fremstad's secrets. The real machinery is all behind the brows. Mme. Fremstad herself says: "Even the voice is not a physical attribute. It belongs to one's soul rather than to one's body. When I was studying Salome, I discovered that you can not even be wicked with your body. A little wickedness is as stupid as any other kind of mediocrity. If you are going to be wicked, you must be very wicked, and you can be that only with your mind and your voice. Your body can't accomplish much. To leave out a hip or a shoulder, that is mere stupidity. Wickedness, to be interesting, must be something active, not a lack of clothes."

Circumstances have never helped Mme, Fremstad. She grew up in a new, crude country where there was neither artistic stimulus nor discriminating taste. She was poor, and always had to earn her own living and pay for her music lessons out of her earnings. She fought her own way toward the intellectual centers of the world. She wrung from fortune the one profit which adversity sometimes leaves with strong natures—the power to conquer. Wagner once said that the bigger the bell, the more difficult it is to release its tone: a sleigh-bell will tinkle to the tap of the finger-nail, but to ring a great bell one must strike it with a hammer. It is only within the last eight years that Mme. Fremstad has disclosed the scope of her artistic and intellectual powers. Goethe said: "There are many kinds of garlands; some of them may be easily gathered on a morning's walk." There are others that are unattainable—that no one has ever gathered, and no one ever will. But the pursuit of them is one of the most glorious forms of human activity.

FARRAR'S impersonation of Madame Butterfly is so Japanese in appearance, in posture,

and movement, that it has been marveled at by the Japanese themselves

Copyright, Aimé Dupont

FARRAR'S impersonation of Madame Butterfly is so Japanese in appearance, in posture,

and movement, that it has been marveled at by the Japanese themselves

Copyright, Aimé Dupont