McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 40 (March 1913): 63-72.

PLAYS OF REAL LIFE

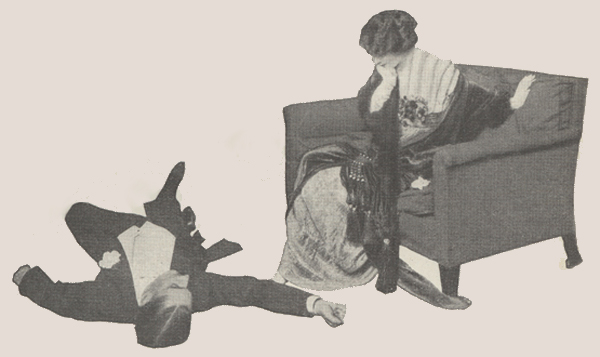

"Within the Law"—Act III

"English Eddie" and Mary Turner. Jane Cowl as the heroine made one of the most successful

impersonations of the season

"Within the Law"—Act III

"English Eddie" and Mary Turner. Jane Cowl as the heroine made one of the most successful

impersonations of the season

UNQUESTIONABLY the most interesting plays produced in New York this winter before the first of January were "Milestones," "Fanny's First Play," "Hindle Wakes," and "The Mind the Paint Girl." A dramatic season that presents four pieces so fresh and unhackneyed must be accounted a good one.

Sir Arthur Pinero's "The Mind the Paint Girl" seems to have been suggested by the fact that marriages between young English noblemen and music-hall favorites are growing more and more usual, and it deals with the attraction that musical-comedy girls have for young men of Lord Farncombe's class. Since the girls themselves are only a part of this attraction,—a good deal of it lies in their atmosphere, the highly colored world in which they live and do or do not "mind the paint,"—the play is primarily a picture of a kind of life, a kind which young men of gentle breeding find irresistibly alluring.

The story is slight: Lily Parradell—born in a little grocery shop across the river, work-girl in a factory when she was ten, taught out of charity by an old dancing master—has fought her way up until she is the reigning favorite at the Pandora, the foremost musical-comedy theater in London. Young Viscount Farncombe is in love with her and wishes to marry her. On the one hand there is Farncombe, not at all a fast boy, rather dull, rather timid, rather bored, but thoroughly decent and so little of a snob that he is not daunted by Lily's old mother, who has not changed in the least since she kept the grocery shop. On the other hand there is Lily Parradell and her "world," into which the well-behaved young lord wistfully gazes. To say that the play is diffuse is superficial. Its object is to depict this "world" of musical comedy—the girls who shine in it, the men who finance it, live on it, write for it, hang about it. The large cast, the brilliant ensemble scenes, every line of the dialogue, go to construct this picture. The story of what actually happened between Lily Parradell and Farncombe is scarcely more than a pretext upon which we are introduced into the life and atmosphere of "The Mind the Paint Girl" and her kind.

Lily Parradell has heeded the warning of the song in which she made her first success, has minded the paint, and, to the great satisfaction of her old mother, has "kept herself respectable." In the first act we are introduced to Lily on her birthday, when her friends are calling to offer their congratulations. The second act presents a birthday dance and supper given for her by the management in the green-room of the Pandora, with Pinero's long cast of characters artfully massed and managed, and with all the persons and motives of the music-hall world in motion. Here Pinero's intimate knowledge of this world makes itself felt. The act scarcely advances the story at all; in so far as the plot is concerned, nothing happens, except that Lily gives Farncombe a few more dances than she had meant to. Yet the act is full of movement and color. Read from the page, it would seem confused and meaningless. The dialogue is contrapuntal, wonderfully orchestrated, spoken by a score of persons who rush upon the stage en masse or weave in and out of the picture in couples, presenting and actualizing a kind of society. The people who make up this society are so well known to Pinero that he can characterize them by a line, a gesture, a grimace. There is the manager of the Pandora, who knows his girls and his public and the value of patrons like Farncombe. There are Lily's colleagues: the hard one who wrings a month at Ostend out of the agonized German Baron, and the soft one who purrs a new motor-car out of the lisping Jew, De Castro. There is Vincent Bland, the song-writer, and Lal Roper, stout and middle-aged, who has a business in the City and lives to follow the lights of the Pandora.

ROLAND YOUNG AS ALAN JEFFCOTE, THE MILL-OWNER'S SON, IN "HINDLE WAKES"

ROLAND YOUNG AS ALAN JEFFCOTE, THE MILL-OWNER'S SON, IN "HINDLE WAKES"

The two remaining acts of the play take up and put through the story of Farncombe's courtship, and the retirement in his favor of his rival, Captain Jeyes, an army officer who resigned his commission because his regimental duties took him too far from the Pandora, and who for six years has hung about London to take Lily Parradell to and from the theater, and to suffer tortures of jealousy every day of every week, as new worshipers came and went. Jeyes is a very significant figure of the Pandora world—the young man who insists upon being romantic and ruining himself, who seems to have been especially created to nourish the vanity of actresses. "Catnip men," a French actress once called them.

Miss Billie Burke, as the heroine, did much to give the play verisimilitude. She had the manifest advantage of being, in a sense, the character. If the part had been more warmly done, it would probably have been less true. The rather tight, dry style, with a little rasp in it, seems to be what is needed here. Both Miss Burke and Sir Arthur Pinero know what it is that "comes across" in the music-hall.

WHIILE "Fanny's First Play" can by no means be ranked among Mr. George Bernard Shaw's best plays, it is one of the most amusing, and its unconventionality pleased the New York public. Mr. Shaw sets out to ridicule certain conventions—theatrical conventions, domestic and social conventions. Miss Fanny O'Dowda, a student at a woman's college in Cambridge and member of a socialist society, has written a play, and her father arranges to have it produced on her birthday—produced by a professional company, with the London critics in attendance to pass judgment upon the piece. Count O' Dowda, an esthetic survival of the eighteenth century, has not read the play himself, and probably would not have understood much of it if he had. The name of the author is withheld from the company and critics, as Miss O' Dowda wishes no allowance made for her youth and sex.

On the evening when the play is to be given,

SCENE FROM THE SECOND ACT OF "MILESTONES," IN WHICH JOHN RHEAD'S DAUGHTER EMILY IS

FORCED BY HER FATHER TO MARRY LORD MONKHURST

the critics meet at Count 0' Dowda's house and before dinner deliver themselves upon

plays and play-writing in general. They insist upon knowing the authorship of the

play they have come to see. "How," says Gunn, "is one to know what to say about a

play, if one doesn't know the author?" Says Bannel: "You wouldn't say the same thing

about a Pinero play and one by Henry Arthur Jones." After this introduction follows

Fanny O'Dowda's play, in three acts. When Fanny's play is over, the critics come forward

and attempt to decide upon the authorship. In attempting to place the play in the

right locker, the critics take up the best known English playwrights one after another,

and, in their own way, define the work of Mr. Shaw and his contemporaries, tagging

each playwright by some external and unimportant characteristic that has nothing to

do with his real manner or method, much less with his dramatic purpose. They characterize

each brand of modern play by comments which remind one of the woman who said she "could always tell Meredith's style, because there

were so many parentheses."

SCENE FROM THE SECOND ACT OF "MILESTONES," IN WHICH JOHN RHEAD'S DAUGHTER EMILY IS

FORCED BY HER FATHER TO MARRY LORD MONKHURST

the critics meet at Count 0' Dowda's house and before dinner deliver themselves upon

plays and play-writing in general. They insist upon knowing the authorship of the

play they have come to see. "How," says Gunn, "is one to know what to say about a

play, if one doesn't know the author?" Says Bannel: "You wouldn't say the same thing

about a Pinero play and one by Henry Arthur Jones." After this introduction follows

Fanny O'Dowda's play, in three acts. When Fanny's play is over, the critics come forward

and attempt to decide upon the authorship. In attempting to place the play in the

right locker, the critics take up the best known English playwrights one after another,

and, in their own way, define the work of Mr. Shaw and his contemporaries, tagging

each playwright by some external and unimportant characteristic that has nothing to

do with his real manner or method, much less with his dramatic purpose. They characterize

each brand of modern play by comments which remind one of the woman who said she "could always tell Meredith's style, because there

were so many parentheses."

This divertissement by the dramatic critics by no means exhausts the satiric humor of the piece, though it seems to have attracted more attention than anything else in the play, both here and in London. The complexion of Fanny's budding talents seems to have afforded Mr. Shaw a great deal of amusement; he fairly outdoes himself to be shocking in the play he makes Fanny write. He seems to relish the notion of attributing a flippant and rather "raw" burlesque on the respectable, middle-class English home to a young girl, gently bred. This, Mr. Shaw seems to chuckle, is the sort of thing young ladies who are impelled toward literature are thinking about to-day.

But to Fanny's own play. Knox and Gilbey are partners, drapers, most respectable. Margaret Knox is betrothed to Bobby Gilbey—both young people have been reared in the pure atmosphere of the British tradesman's home, and both are being carefully educated. Margaret, whose mother is a religious fanatic, has had rather more than her fair share of cant. But both young people, according to Fanny, are quite unregenerate, normal savages, absolutely untouched by the moral and social standards under which they apparently live. Margaret, to give vent to her high spirits on a boat-race night, goes alone to a public dance-hall, picks up as escort a French naval officer whom she has never seen before, and, when the police raid the place, knocks out an officer's two front teeth with a well aimed blow. She and her escort are taken to Holloway jail and locked up for two weeks.

Bobby goes out for a lark with "Darling Dora," a little girl who lives

FANNY HAWTHORN, THE REBELLIOUS HEROINE IN "HINDLE WAKES," AS PLAYED BY MISS EMELIE

POLINI

as she can and who has been in jail before. They go to a dance-hall, drink too much,

exchange hats, and walk about the streets singing until they are sent to jail for disturbing the peace and resisting arrest. And yet these are all, as they say in New England, pleasant young people, not at all vicious or unattractive. Even "Darling Dora,"

Fanny thinks, is not in the least a degraded person. Here, says Fanny, we have the

normal young of the species, expressing their healthy animal spirits. That they get

locked up is, of course, an accident for the young people, a structural convenience

for Fanny. But neither Fanny nor Bobby nor Margaret regard two weeks in jail as a

retribution—the blush is for the jail!

FANNY HAWTHORN, THE REBELLIOUS HEROINE IN "HINDLE WAKES," AS PLAYED BY MISS EMELIE

POLINI

as she can and who has been in jail before. They go to a dance-hall, drink too much,

exchange hats, and walk about the streets singing until they are sent to jail for disturbing the peace and resisting arrest. And yet these are all, as they say in New England, pleasant young people, not at all vicious or unattractive. Even "Darling Dora,"

Fanny thinks, is not in the least a degraded person. Here, says Fanny, we have the

normal young of the species, expressing their healthy animal spirits. That they get

locked up is, of course, an accident for the young people, a structural convenience

for Fanny. But neither Fanny nor Bobby nor Margaret regard two weeks in jail as a

retribution—the blush is for the jail!

When Margaret finds out that she likes liberty, she is honest about it; she says she enjoyed the dance-hall and the street fight; she conceals nothing about the policeman's teeth, not even the teeth themselves, which she keeps as a trophy; and she avows that she has long been in love with Bobby's butler. But living under a respectable roof, and expressing his youth under cover, has made a sad sneak of Bobby. He cuts his little Dora when he is out walking with his mother, and coaxes the butler to tell him how he can break his engagement and put all the blame of it on Margaret. And Fanny does manage to put the onus of Bobby's unattractive qualities on his respectable bringing up. He is certainly more likable in his natural unregenerateness than when he tries to conform to what he thinks respectable. One imagines that "Darling Dora" sees the best of him, when he "always imagines himself a kitten and bites her ankles coming up the stairs."

In the last act the old gods of the British hearthstone meet their twilight, crumble to dust at the thrust of Fanny's bold quill. Everybody takes down the Sunday shutters and lays bare the windows of his soul: Bobby declares that he will have nobody but his Dora; Margaret proclaims her love for the butler; the butler modestly confesses that he is the son of a duke, that his older brother has just died, and that he has succeeded to the title; Margaret's fanatical mother admits that she is not so sure about the "inner light," after all; and the two drapers, Knox and Gilbey, resolve to take a highball and be less respectable in the future. One can't help wondering whether Fanny would advise a similar relaxation in all British households, and where, if it occurred, she thinks we would come out. Fanny has her own engaging ideas to tie to; they will always keep her up to a certain pitch. But people without ideas must have something. The question is, whether Fanny might not find Knox and Gilbey less interesting, unrespectable than respectable; and Mrs. Knox's hysteria might easily take a more offensive form than religious mania.

A PLAY that every one hoped to find interesting was Mr. Edward Sheldon's "The High Road." This expectation seemed warranted both by the fact that Mrs. Fiske was to play the leading rôle and that the piece was the work of a young playwright of exceptional promise, who has many well-wishers. The play was, however, a disappointment, and left New York after a run of two months.

"The High Road" purports to deal with the new activities of women, and the kind of woman such activities develop.

The first act opens on an up-State farm, shut in by hills, where Mary Page is the drudge of a brutal old father who has worked his wife to death and is now grinding his daughter down in the same routine of farm chores. Young Alan Wilson, son of a millionaire, who has been sketching in the country and boarding at the farm-house, at the end of the first act persuades Mary to run away with him to see the world. Throughout the act the dramatist endeavors to disclose in her such unusual qualities of mind and feeling as to warrant this unusual behavior. But Mr. Sheldon sets about proving his point in exactly the wrong way. He makes the girl bookish; she talks too much and too glibly about what she has learned at school and observed in nature. Only Mrs. Fiske's natural and unemphatic acting saved the character from self-consciousness and artificiality. It would be hard to find a stronger instance of ineffective dramatic preparation.

Even in a novel, self-revelation of the kind the author has put upon Mary Page would

be superficial and artificial. The character is not treated imaginatively; it is done

from the outside. One feels no emotional depth in the girl. Her desire to see beyond the hills that

shut in her father's farm, to find wider horizons where her soul can have room to

grow, is the theme of the first act—indeed, of the play. But there is nothing here

to convince one that this feeling is different from any little country girl's desire

to see the world. In the long monologues that the author has set down for Mary, there

is nothing to denote either strong feeling or the imaginative quality which he seems

to wish her to possess. It is not the child who "makes up" things who is imaginative. The child who tells

you she is always finding portraits and landscapes in the clouds, for example, is

not an imaginative child, but a commonplace child. No young girl who had in her the

feeblest germ of poetic feeling would, after reading "Romeo and Juliet" for

SCENE FROM "THE MIND THE PAINT GIRL." MISS BILLIE BURKE AND MR. HERBERT, WHO PLAYS

CAPTAIN JEYES, THE JEALOUS LOVER WHO HAS THROWN BY HIS CAREER TO FOLLOW THE STAR OF

THE PANDORA

the first time, close the book and name her dog Romeo—a dog that was already named

Abraham Lincoln! A girl who would do that would never do anything very rash. Any political

aspirant would be safe in marrying her; she would have a spotless past.

SCENE FROM "THE MIND THE PAINT GIRL." MISS BILLIE BURKE AND MR. HERBERT, WHO PLAYS

CAPTAIN JEYES, THE JEALOUS LOVER WHO HAS THROWN BY HIS CAREER TO FOLLOW THE STAR OF

THE PANDORA

the first time, close the book and name her dog Romeo—a dog that was already named

Abraham Lincoln! A girl who would do that would never do anything very rash. Any political

aspirant would be safe in marrying her; she would have a spotless past.

Synge, in his little play "In the Shadow of the Glen," makes us feel the reality of such emotion and such imagination in an illiterate Irish peasant woman. When she walks off with the tramp in the end, we know there was nothing else for her to do.

The second act, three years later, finds Mary Page living as Alan Wilson's mistress in a sumptuous apartment on Riverside Drive, surrounded by Titians and Giorgiones. She has tired of idleness and luxury, and has decided to leave Alan and go to work in a shirt-waist factory for six dollars a week. Again Mr. Sheldon uses the external method. There is not one incident to show us that her present life has become intolerable to her, and nothing, beyond a marked volume of Karl Marx on her table, to show us that she has become interested in working-girls. Mary is left to explain her motives to Alan Wilson and to the audience. Many of her lines here are very moving, and Mrs. Fiske read them with great sincerity and beautiful feeling. But they were not enough. To be effective, this explanation with Alan should come after some incident which made us feel the birth of new sympathies and aspirations in Mary Page. An audience can not reach a sympathetic understanding of an emotional, much less a spiritual, revolt in a woman merely by hearing her argue her case, even though she argues well.

When Mary Page leaves Alan, she has done very little to prove that she is different from any other young woman who might have been found living in his apartment. Everything is before her to do; she has to make her own life, atone for a disastrous if not a fatal mistake. She has certainly something to make up to herself. But the eighteen years in which she accomplished this, in which she struggled and suffered and grew stronger, and began to help other struggling women, are a closed book to us. We do not meet Mary Page, from the night she left Alan Wilson's apartment, until we meet her in the Governor's office at Albany, a "public woman," president of the Women's Industrial League, author of many books dealing with industrial problems. Miss Page marries the Governor, assists him in his campaign when he is a candidate for the Presidency, and is threatened with exposure by a capitalist who once met her in Wilson's flat, and whose interests her husband's intended industrial reforms would jeopardize. This is all familiar dramatic material. These situations have been used for heroines of every sort, and they are not used here in a way that reveals anything of Mary Page's real nature. The third act brings us not much nearer to her than "Who's Who" would do; it is a mere inventory of her activities. In the fourth act she is caught in an old trap, and in the fifth she extricates herself in a way not new.

The growth of the girl who left Wilson's flat, that night, into a woman who works

for other women, would be an interesting development to follow; and such a character,

made real and living, would be fresh dramatic material. But Mr. Sheldon omits her

struggle, everything

"Within the Law"—the thieving shop-girl who let Mary Turner go to prison on a false

charge

"Within the Law"—the thieving shop-girl who let Mary Turner go to prison on a false

charge

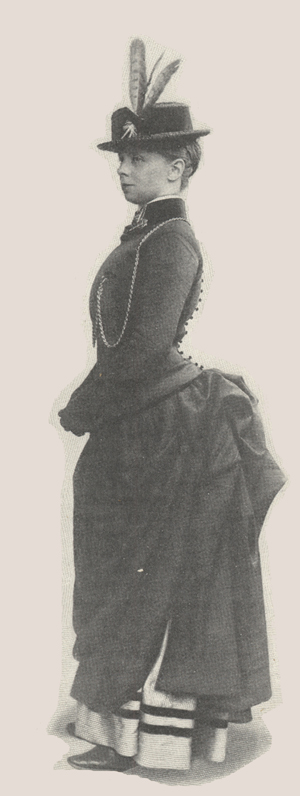

Mrs. Fiske as the woman reformer in "The High Road"

EDWARD SHELDON'S "THE HIGH ROAD" AND BAYARD VEILLER'S "WITHIN THE LAW" BOTH DEAL WITH WORKING-GIRLS. IN MR. SHELDON'S PLAY THE

WORKING-GIRL BECOMES A REFORMER AND "PUBLICIST"; IN MR. VEILLER'S SHE BECOMES A CLEVER

ADVENTURESS WHO SWINDLES WITH IMPUNITY BY KEEPING "WITHIN THE LAW"

that made her what she was, and asks us to take the really dramatic part of her life

for granted. When he brings her upon the stage again, a finished product, the situation

with which she is confronted is such as might confront any woman who had something

to conceal, and who had married a public man. The heroine in Mr. Fagan's "The Earth"

(played by Lena Ashwell) was confronted by a situation almost identical, and she extricated herself in the

same way. There is nothing in the action here to define Mary Page's character, any

more than there is in the dialogue of the first acts. The curtain falls, and the woman

reformer escapes unpresented.

Mrs. Fiske as the woman reformer in "The High Road"

EDWARD SHELDON'S "THE HIGH ROAD" AND BAYARD VEILLER'S "WITHIN THE LAW" BOTH DEAL WITH WORKING-GIRLS. IN MR. SHELDON'S PLAY THE

WORKING-GIRL BECOMES A REFORMER AND "PUBLICIST"; IN MR. VEILLER'S SHE BECOMES A CLEVER

ADVENTURESS WHO SWINDLES WITH IMPUNITY BY KEEPING "WITHIN THE LAW"

that made her what she was, and asks us to take the really dramatic part of her life

for granted. When he brings her upon the stage again, a finished product, the situation

with which she is confronted is such as might confront any woman who had something

to conceal, and who had married a public man. The heroine in Mr. Fagan's "The Earth"

(played by Lena Ashwell) was confronted by a situation almost identical, and she extricated herself in the

same way. There is nothing in the action here to define Mary Page's character, any

more than there is in the dialogue of the first acts. The curtain falls, and the woman

reformer escapes unpresented.

THE working-girl seems to be a tempting bait to playwrights just now. Mr. Bayard Veiller, in his play "Within the Law," has taken a nibble at it. His play, though much less ambitious than Mr. Sheldon's, is, on the whole, more interesting and consistent. The story of the working-girl who is falsely charged with theft, who is imprisoned and afterward comes out to prey upon society, is not new; but Mr. Veiller has taken it up from a new angle and has told it in a stirring melodrama. When the injured girl is being sent away to prison, she breaks out in an appeal to her employer, revealing to him some of the hard conditions that drive shop-girls to steal. From the enthusiasm with which the audience received this speech night after night, one might predict that very substantial rewards await the man who is enough in sympathy with these things to write a play about real working-girls and their problems.

THE only play given in New York this season that touched upon the feminist movement or the industrial position of women at all vitally was Stanley Houghton's new play, "Hindle Wakes." The play did not meet here with a shadow of the success it had in London. It is written in the quiet tone popular among the younger English dramatists, who are so determined not to be artificially conclusive that they are sometimes more inconclusive than they need be. But they are certainly bringing to the stage fresh material; and, cutting into new cloth, they have the right to cut it to a new pattern. The plot is slight, but the characters are very real people, with clearly defined individuality, and the dialogue is living human speech, colored by strong human feelings.

The play begins in the cottage of a workman in the textile district of England. Old Christopher Hawthorn and his wife are awaiting the return of their daughter, Fanny, a weaver in the mills, who went away with her friend Mary to spend Bank-holiday in a neighboring town. The old couple have learned that Fanny left Mary, and has deceived them as to her whereabouts. When Fanny returns, she tries to stick to her deception; but when she learns that Mary was drowned by the capsizing of a pleasure boat, on the day she left her, Fanny breaks down and admits that she motored to Llandudno with Alan Jeffcote, the mill-owner's son, and spent the week-end with him there.

Old Christopher goes up to the mill-owner's house that night. Christopher and old Jeffcote had been workmen together when they were lads. In a splendid scene between these two old men—a scene that lets one into their natures and the story of their lives—Jeffcote promises Christopher that Alan shall break off his engagement to Sir Anthony Farrar's daughter and shall marry Fanny Hawthorn. After the old weaver's departure, young Alan comes home in his car, and his father has the matter out with him. In spite of his behavior with Fanny, Alan is in love with the girl to whom he is engaged, and he refuses to break with her. But his father is inexorable. After painful scenes with his sweetheart, Alan's engagement is broken. Old Jeffcote sends for Christopher Hawthorn to bring his wife and daughter up to the house and arrange for the marriage. Fanny comes in with her mill-girl's shawl over her head, sits down, and does not open her mouth while the Hawthorns and Jeffcotes arrange the marriage. When they come to the question of whether the wedding shall be a large or small one, they ask her which she would prefer. Fanny begins to laugh and says she wonders that they should consult her. She's sorry they've been put to such trouble, for she's not going to have any wedding at all. She's never had the least notion of marrying Alan Jeffcote. He is a good fellow, well enough to have a lark with, but she means to have a very different sort of husband; she is not going to marry out of her class. Alan doesn't owe her anything, that he should be saddled with her. She went with him to Wales for her own amusement, not for his. Even Alan is shocked to hear this, and old Mrs. Hawthorn flies into a rage and tells Fanny that she can never come home.

Very well, says Fanny. She doesn't need her father's roof any more than she needs Alan's. She is a skilled workwoman, and as long as there is weaving to be done in England, she can always make good wages. She promises her father that she will not disgrace him,—one somehow believes she means it,—says good night, and walks out to take care of herself—which she is much more capable of doing than Alan would be if he were driven out from home. There the play ends. It would have been comforting to the conventional-minded if Mr. Houghton could have added another act showing us where we would find Fanny in, say, five years—whether she was really able to live up to her liberty, whether she recovered from her indiscretion as a young workman would, kept her head, and made the most of her life and her skill. Probably Mr. Houghton would say: " Here is the situation; I don't know where it's leading any more than any one else does."

NATHANIEL JEFFCOTE, THE OLD MILL-OWNER, THE STRONGEST FIGURE IN "HINDLE WAKES," WHO

SWEARS THAT HIS SON SHALL MARRY THE MILL-GIRL HE HAS COMPROMISED

NATHANIEL JEFFCOTE, THE OLD MILL-OWNER, THE STRONGEST FIGURE IN "HINDLE WAKES," WHO

SWEARS THAT HIS SON SHALL MARRY THE MILL-GIRL HE HAS COMPROMISED

"MILESTONES," by Arnold Bennett and Edward Knoblauch, is certainly the most strikingly original play brought out this season. The conflict between youth and age has never before been introduced upon the stage in quite the same terse, direct way that Mr. Bennett presents it, and his novel treatment has given to a very quiet play an almost sensational quality. The plot is by this time known to every one. In the same London drawing-room we see three successive generations of youth, on fire with love, dreams, ideas, come up against the unimaginativeness, the fading mental vision, the cooling arteries, of age. We see each young man when he is big with the idea that is to register him in the world; either he must eat his grandfather or throttle his idea. Although the acts of the play are twenty-five years apart, the playwrights have, in effect, preserved the dramatic unities. The three acts occur in the same room of the same house,—done over to suit the fashion of each period,—and the playwrights are regarding time from the scientific standpoint, as always the same.

The objection has been made that in "Milestones" there is no progression, that the same thing happens over and over in each act, and that each act presents a new set of characters. But this is not the case. In each act the force of the new generation manifests itself in an entirely different manner from that of the generation before. It not only proposes to do something different: it behaves differently, has a tone and color of its own. Nor does each act introduce a new set of characters. John Rhead, splendidly impersonated by Mr. Leslie Faber, dominates the play from first to last; he remains the powerful personality, long after the fire has gone out of him. When we see him in the later acts, with his dull, burnt-out eyes, his imagination dead, his charge spent, we feel that he is still the finest figure among them. His teeming date is drunk up with time, and it is the young fellows who are doing things now. But his fruitful hour, while he had it, was richer than theirs, his dream was bigger, and it has left a noble stamp upon him. Even the Honorable Muriel, his Suffragette granddaughter, who has the most modern ideas about parental authority and often loses patience with her grandfather's domineering ways, admires him.

EDITH BARWELL, WHO DOES A SPLENDID CHARACTER BIT IN "MILESTONES" AS NANCY, THE TYPEWRITER GIRL FROM YORKSHIRE, WHOM CONSERVATIVE

MR. SIBLEY MARRIES

EDITH BARWELL, WHO DOES A SPLENDID CHARACTER BIT IN "MILESTONES" AS NANCY, THE TYPEWRITER GIRL FROM YORKSHIRE, WHOM CONSERVATIVE

MR. SIBLEY MARRIES

After all, old John had his way with two generations; in his youth, when he dreamed of iron ships, and in his middle age, when he bullied his daughter into marrying Lord Monkhurst. It takes the third generation to eat him! But in the Honorable Muriel he meets his match. She doesn't make scenes, but she isn't in the least afraid of them, and she won't be bullied. On his golden-wedding night she puts the old man in a fury by announcing her engagement to her cousin Dick. John's women-folk have always been his slaves. When he asked Rose to marry him, in his splendid youth, she told him that "he could never know how much she wanted to be his slave." His sister, Gertrude, broke off her engagement out of loyalty to John's idea, and remained a dependent spinster all her life, to be patronized and humiliated by her brother. John's daughter belonged to a soft period, when "The Mikado" was young, when Ouida's novels were called "light reading" and William Morris "solid reading." John had an easy victory with her. But the Honorable Muriel simply amazes him. She is so pretty, candid, truthful, so easy and sincere. None of the old sentimental tricks, by which daughters and granddaughters are usually worsted in argument, have any effect upon her. She remains calm and reasonable and unshaken. She will marry Dick because they can't give her any good reason why she shouldn't.

No wonder that, as John Rhead sits by the fire that night, with the old wife whom he has loved and ruled for fifty years, listening to the cracked singing of the old sister whom he has bullied ever since she was born, he says: "All the same, I have said it before and I say it again: the women aren't what they were in my young day. They lack"—with an inclination toward his old wife—"they lack charm!" At this moment the door opens and Muriel comes softly in to make it up to the old man whom she has vexed. Then comes one of those moments which occur so seldom on the stage, and which are remembered so long and so gratefully. Not a word is spoken. The girl goes up to the old man, leans over him, and holds her cheek against his. Then she takes a rose she is wearing, kisses the heart of the flower, and leaves it in her grandfather's hand. Old John's eyes follow her retreating figure, and when the door closes he shakes his head and murmurs to his wife: "We live and learn, we live and learn." Fortunate the play that has such an ending!

The play is almost without apparent "construction." One never hears the click of its machinery. There are no "big scenes" artificially brought about for their dramatic effectiveness, no overheard conversations, no accidental meetings or unlikely coincidences. The inherent vigor of the motive carries the play through. It is like a spiral spring; once released, it will go its length without any prodding. The dialogue, too, is simple. There are no brilliant speeches. The lines are homely, commonplace in themselves, the plain speech of living people. But they are intensely dramatic, none the less, because of the situations that lie behind them. And the situations are dramatic, not in themselves, but because one is interested in the characters concerned in them. All good plays begin with the author's power of creating character. If his people are real enough and interesting enough, anything that happens to them is interesting. If his characters are thin, then his ingenuity must be great to hold our attention at all. People, not an order of events, are the real excitement of the drama. One might almost say that on the stage only the intensely personal and the strongly individual is really interesting. The dramatist outlives his plays.

Of course, the fundamental reason that "Milestones" is a good play is that Mr. Arnold Bennett is a very individual writer, with certain very clearly marked sympathies. His literary personality is the living breath that animates the play. The themes of this play are the same as those in his best novels—his sympathy with women, for example, as the burden-bearers of the social order and of the old sentimental ideals of family life. That solid old institution, the middle-class family, he regards as a sort of sullen idol that can be propitiated and kept smiling only by the sacrifices of women: of the servant who drudges herself into a sexless machine in the kitchen; of the spinster who is condemned to a parasitic existence under some roof where she must help to keep the big god bright; of the young girls who are kept at home and cheated of their chance to live in order that they may minister to the comfort of the old and the unfeeling.

The major theme of the play is that which Mr. Bennett treated with so much sympathy and insight in his novel "The Old Wives' Tale"—the conflict between youth and age, the unintentional, unavoidable cruelty of the old toward the young, and of the young toward the old. No writer, except Tolstoy, has ever treated this relation so truthfully or so understandingly. Mr. Bennett takes the biologist's rather than the poet's view of both youth and age. Youth is the only really valuable thing in the world, not because it is "youth," a pretty name, a charming quality, but because it is force, potency, a physiological fact. A kind of power can be extracted from youth that can be obtained nowhere else in the world—or in the stars; and this is the only power that will drive the world ahead. It makes the new machine, the new commerce, the new drama, the new generation; it is Fecundity. The individual possesses this power for only a little while, a few years. He is sent into the world charged with it, but he can't keep it a day beyond its allotted time. He has his hour when he can do, live, become. If he devotes these years to self-sacrifice, to caring for an aged parent or helping to support his brother's children, God may reward him, but Nature will not forgive him. The kind of self-sacrifice that has so long been accounted a virtue, which is the very corner-stone of the old family ideal, Nature punishes more cruelly than she does any other mistake.

Nobody has dealt more feelingly and appreciatively than Mr. Bennett with the charm of age, and nowhere has he made it more felt than in "Milestones." People are in many ways more interesting after they have lost their rocket quality. But the world could get on without the old; without the young it can not.