McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 42 (February 1914): 41-51.

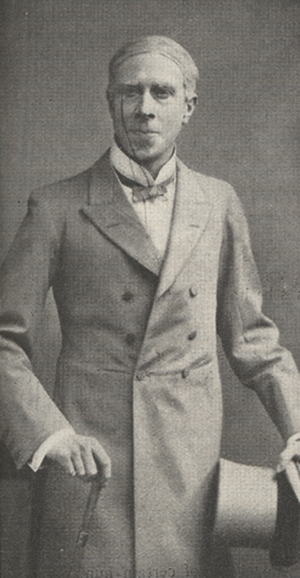

Ethel Barrymore as Tante

Ethel Barrymore as Tante

NEW TYPES OF ACTING

The Character Actor Displaces the Star

EVERY one has heard the story of the American school-girl who, on being taken through Westminster Abbey, came upon the full-length statue of Lord Beaconsfield beside that of Mr. Gladstone, and exclaimed: "Why, there's George Arliss!"

Mr. Arliss' impersonation of Disraeli is unquestionably the most notable piece of

character-acting now before the American public. The play, while it contains good

lines and is touched by that pleasing sentiment for the old times that are not very old which characterizes Mr. Parker's better work,

is by no means a remarkable play. In the hands of an ordinarily good actor it would

have been good for a run of a few months at

"IF THE INSATIABLE American public insists too long on spending its inexhaustible

dollars on 'Disraeli,' it will prove its short-sightedness. Mr. Arliss is one of the

few—alarmingly few!—actors from whom anything new can be expected, who is elastic

enough to be capable of surprises"

most. There is nothing in the part for the ordinary actor to get a hold on. The situations would never get him anywhere, and the best lines, delivered merely as lines, would

soon become hackneyed. Here the play does not at all put the actor through, but the

actor, by his resourcefulnes and adroitness, every night carries the play across.

"IF THE INSATIABLE American public insists too long on spending its inexhaustible

dollars on 'Disraeli,' it will prove its short-sightedness. Mr. Arliss is one of the

few—alarmingly few!—actors from whom anything new can be expected, who is elastic

enough to be capable of surprises"

most. There is nothing in the part for the ordinary actor to get a hold on. The situations would never get him anywhere, and the best lines, delivered merely as lines, would

soon become hackneyed. Here the play does not at all put the actor through, but the

actor, by his resourcefulnes and adroitness, every night carries the play across.

The very fact that the part is so little written, is merely sketched in the playbook, gives an actor of Mr. Arliss' quicksilver-like fancy an opportunity to create the part, in the broadest sense of the word. This he has done largely from a study of Disraeli's letters and novels, from a survey of portraits and reminiscences, of pretty much everything that remains to testify to the personality of Lord Beaconsfield. In his preliminary studies of the character, he went to work very much as a novelist, who was going to build a romance around the character of Disraeli, would have done. The play owes its most unusual popularity not to anything remarkable that Disraeli says or does, but to the remarkable degree in which George Arliss becomes Benjamin Disraeli. His personal contribution to the play is so great that the piece is forgotten in the character. One often hears that this play has a fine ending. As a matter of fact, the play has no ending at all. When the actor takes Lady Beaconsfield's hand and advances to meet an invisible Queen, he makes a good curtain by sheer will power, or by something akin to it.

It matters very little whether an artist's presentation of a historic character is

historically accurate, if it is convincing as a personality. In this case, however, it seems highly

probable that the actor produces in figure, face, and manner very much such a man as Lord Beaconsfield appeared

"Mr. Arliss has never done anything more finished than the Duke of St. Olpherts, in

'The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith,' which he played when he first came to the United States,

twelve years ago"

"Mr. Arliss has never done anything more finished than the Duke of St. Olpherts, in

'The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith,' which he played when he first came to the United States,

twelve years ago"

"We have no other actor who can get inside the skins of so many different kinds of

people. His Disraeli, though a more sympathetic part to his audience, is no more fully

realized than his Marquis of Steyne"

to the eyes of the curious. Mr. Arliss manages to suggest the wisdom of a very wise old race, the long vision, the florid imagination—tempered by the hardest kind of business sense—which made Disraeli such an anomalous figure in English politics. The play

gives him ample opportunity to display the courtiership and the rare tact with women

which were such important factors in Disraeli's career. From his perfect manner with Lady Beaconsfield, with the girl whose lover is sent to Cairo, with the adventuress whose cleverness

he enjoys but whose mistakes bore him, one can readily believe in his influence with

the Queen—an influence which Gladstone complained was "practically unlimited." Prince Albert, we are told, never wholly trusted the Jewish politician, but, after the death of her Consort, Victoria was more and more open to Disraeli's

suggestions. He was, she said, the only one of her ministers who did not talk at her

as if she were a public meeting. After the bluntness of her Scotch and Welsh and English

advisers, she found Disraeli's softer methods, his perfect courtiership, the ingratiating personal note in his intercourse with her, very grateful. He knew how to flatter

her, both as a Queen and as a woman. In his homage to the wife, older than himself

and his benefactor,—a gallantry never too light, never too heavy,—Mr. Arliss' Disraeli suggests a personal quality

which might well have gone far with a Queen so surrounded by obstinacy and by policies

that usually defeated her dearest ends.

"We have no other actor who can get inside the skins of so many different kinds of

people. His Disraeli, though a more sympathetic part to his audience, is no more fully

realized than his Marquis of Steyne"

to the eyes of the curious. Mr. Arliss manages to suggest the wisdom of a very wise old race, the long vision, the florid imagination—tempered by the hardest kind of business sense—which made Disraeli such an anomalous figure in English politics. The play

gives him ample opportunity to display the courtiership and the rare tact with women

which were such important factors in Disraeli's career. From his perfect manner with Lady Beaconsfield, with the girl whose lover is sent to Cairo, with the adventuress whose cleverness

he enjoys but whose mistakes bore him, one can readily believe in his influence with

the Queen—an influence which Gladstone complained was "practically unlimited." Prince Albert, we are told, never wholly trusted the Jewish politician, but, after the death of her Consort, Victoria was more and more open to Disraeli's

suggestions. He was, she said, the only one of her ministers who did not talk at her

as if she were a public meeting. After the bluntness of her Scotch and Welsh and English

advisers, she found Disraeli's softer methods, his perfect courtiership, the ingratiating personal note in his intercourse with her, very grateful. He knew how to flatter

her, both as a Queen and as a woman. In his homage to the wife, older than himself

and his benefactor,—a gallantry never too light, never too heavy,—Mr. Arliss' Disraeli suggests a personal quality

which might well have gone far with a Queen so surrounded by obstinacy and by policies

that usually defeated her dearest ends.

The lines of the play give the actor an opportunity to display that light and brilliant irony which so maddened Disraeli's British opponents, his imperviousness to insult, his dispassionateness, and his tolerance of passonate convictions in others—when they could be made to serve his purposes. His speech to the president of the Bank of England is sufficient guaranty of the oratorical powers one might expect of him in the House of Commons. Although the play deals with the lighter side of Disraeli and the parlor side of politics, Mr. Arliss makes the audience believe in the public man. Just as one feels the presence of the Queen in the last act, though she does not appear, so throughout the play one feels the presence of the historical Disraeli.

"Disraeli" is now on the road—in its fourth season—after long runs in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. Since Rip Van Winkle, no character part has so got through the heads of the unthinking millions and become a household word. People go to see the play, and then go again and take the children and the grandchildren. Mr. Arliss could probably play Disraeli to good business for the rest of his natural life-time. Usually, when a man becomes identified with one part, it means that he has found the part of his life. Most actors, in the summing up, play only one part under many names; all their impersonations are first cousins, if not brothers. But Disraeli is not in the least better done than any one of a dozen other parts that George Arliss has played here. It is only very different from any of them. He has never done anything more subtle and finished than the Duke of St. Olpherts, in "The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith," which he played, when he first came to the United States, with Mrs. Patrick Campbell twelve years ago. His Disraeli, though a more sympathetic part to his audience, is no more sharply defined or fully realized than his Marquis of Steyne in Mrs. Fiske's production of "Vanity Fair," his Assessor Brack in "Hedda Gabler," or the degenerate youth he played in "Leah Kleshna." A delightful instance of his facility in lighter parts was his portrayal of the young Englishman in Langdon Mitchell's play, "The New York Idea." All these characters have a different way of walking, standing, sitting; no two of them use their hands in the same way. The hands of the Marquis of Steyne and those of Disraeli are as different in look and habit as hands could well be. We certainly have no other actor who can get inside the skins of so many different kinds of people.

So far, Mr. Arliss has kept the upper hand of his own methods. Every actor with a mortal body has mannerisms; it is only when they become inevitable, when we can anticipate them, that mannerisms are dangerous. Mansfield's execution was warped by an irony often so untimely that it must have been unconscious. Mrs. Fiske's metallic elocution tends more and more to give a certain sameness to all her parts. If the insatiable American public insists too long upon spending its inexhaustible dollars upon "Disraeli," it will prove its short-sightedness. Mr. Arliss is one of the few—alarmingly few!—actors from whom anything new can be expected, who is elastic enough to be capable of surprises. He has remained flexible and versatile, he has not been stamped by the parts he has played or compromised by his successes. He is not looking for a part "something like Disraeli or something like Steyne." What he has done is no indication of what he will do, except in point of excellence.

THE term character part, as it has survived from the old drama, is misleading to-day. Practically all modern plays are chiefly concerned with character, and all the parts are character parts. Even Lear, Othello, and Macbeth, to be played successfully, would now have to be played as character parts, not, as the old tragedians played them, as great personifications of certain human passions. In the old plays the character part, which was the most human in the piece, was always subordinate. The star parts were provided with big scenes, moving situations, and long speeches, but were very thinly clad with the vesture of human nature. The actor who played these parts needed to have no very definite ideas about them, or about anything else; he depended almost entirely upon his beautiful voice, his elocution, and his personal beauty or magnetism, as the case might be. Actors like the Kemble men are almost a vanished race. Our actors have to depend much more upon ideas and much less upon special endowments of voice or person than did those who pleased the taste of former generations. As one result, we have fewer great personalities on the stage, but there are certainly more actors of intelligence. Another result of the humanization of the drama is that in our plays the plot interest is much more negligible than it used to be, and the character interest much stronger. This is true not only of "high-brow" plays, but of the most popular forms of entertainment. Indeed, just now it is very "high-brow" to like melodrama, and a thorough-going plot play has the attraction of an exotic.

"You have seen enough of me to learn some of my weaknesses. . . . You are not deep

enough to know what beastly faults of disposition I really have, nor subtle or sympathetic

enough to guess what pain I suffer daily in my own knowledge of them"

ETHEL BARRYMORE in the third act of "Tante"

"You have seen enough of me to learn some of my weaknesses. . . . You are not deep

enough to know what beastly faults of disposition I really have, nor subtle or sympathetic

enough to guess what pain I suffer daily in my own knowledge of them"

ETHEL BARRYMORE in the third act of "Tante"

THE most successful—and the best—play now running in New York, "Potash and Perlmutter," has scarcely a plot at all. It is rather loosely made from Montague Glass' well known stories published in the Saturday Evening Post. Here is a New York play at last. It could not happen anywhere else in the world, though there is not an American in the piece and the only character who speaks conventional English is a Russian refugee. This is not the New York of Babylonian towers and sky-effects which the settlement-house school of poets write about, but it is the city with which the humble resident of Manhattan Island has to reckon and to which he has to adapt himself. The apartment-houses are built for—and usually owned by—Potash or Perlmutter; the restaurants are run for them; the shops are governed by the taste of Mrs. Potash and Mrs. Perlmutter; and, whether one likes it or not, one has to buy garments fundamentally designed to enhance the charms of those ladies.

Of course, Potash and Perlmutter are not the only people in New York. There are also a few Greeks and Italians, and a few people from Cork. But our flavoring extract is Potash and Perlmutter. Whose is the hand that dresses the shop windows along Fifth Avenue? Potash's Whose ladies recline in the limousines that pant in the traffic block? Perlmutter's. In this play you have a group of the people who make the external city, who are weaving the visible garment of New York, creating the color, the language, the "style," the noise, the sharp contrasts which, to the inlander, mean the great metropolis. People who are on their way to something are always more conspicuous and more potent than people who have got what they want and are where they belong. This city roars and rumbles and hoots and jangles because Potash and Perlmutter are on their way to something. Our gorgeous flower shops and diamond shops and fur shops are brilliant largely because Potash and Perlmutter have their romances and their softer hours; and we import more champagne than any other city in the world chiefly because, as Mawruss says, "between friends and partners there should be no stinginess."

Here is another play made by the actors. The jangling partners are a wonderful pair,

and the cast is good throughout. Alexander Carr, as Mawruss Perlmutter, has the most

difficult part in the piece, and produces a really perfect piece of character-acting.

Potash, played by Barney Bernard, is a simpler part, but could scarcely be better

done. Potash is the old-fashioned Jewish

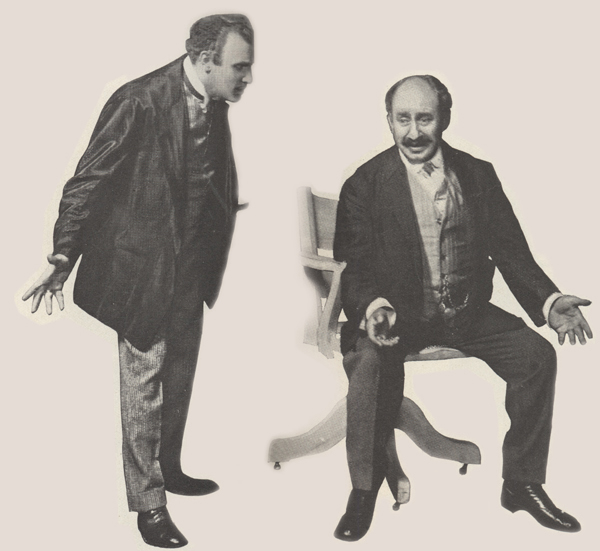

"THE JANGLING PARTNERS are a wonderful pair. Potash (on the right), played by Barney

Bernard, is the old-fashioned Jewish merchant, the unadulterated article, who is always

a salesman, always pushing his line, always a two-price man. But Perlmutter (Alexander

Carr) is a step further on the way. He has learned that there are times when a salesman

mustn't plead, when a business man must be a spender and do things handsomely"

merchant, the unadulterated article, who is always salesman, always pushing his line,

always a two-price man. But Perlmutter is a step further on the way. He has learned

that there are times when a salesman mustn't plead, when a business man must be a

spender and do things handsomely. It comes hard; his mouth gets dry and his hands

get soft and he bites his nails, but he pulls it off. When he declares in his felty

voice that "you can bet your life Mawruss Perlmutter is a gentleman, too," you admit

there's something in it.

"THE JANGLING PARTNERS are a wonderful pair. Potash (on the right), played by Barney

Bernard, is the old-fashioned Jewish merchant, the unadulterated article, who is always

a salesman, always pushing his line, always a two-price man. But Perlmutter (Alexander

Carr) is a step further on the way. He has learned that there are times when a salesman

mustn't plead, when a business man must be a spender and do things handsomely"

merchant, the unadulterated article, who is always salesman, always pushing his line,

always a two-price man. But Perlmutter is a step further on the way. He has learned

that there are times when a salesman mustn't plead, when a business man must be a

spender and do things handsomely. It comes hard; his mouth gets dry and his hands

get soft and he bites his nails, but he pulls it off. When he declares in his felty

voice that "you can bet your life Mawruss Perlmutter is a gentleman, too," you admit

there's something in it.

Both partners are marvelously made-up. Potash's face ought to carry any play; when he is threatened with bankruptcy, it becomes fairly green with misery. Perlmutter is just as sick, but he has acquired the notion that a man must be a good loser, and had better look as if he could pay fifty cents on the dollar. It is a deeply touching moment when Potash says: "And to think it's come to this, that I can't buy my own partner a vedding bresent." When Mrs. Potash laments that they will now have to give up "the new apartment on Riverside Drive, with such a fine view of Grant's Tomb," one would be sorry for her, if one did not know that every lady of her race will eventually get such an apartment, even if we have to build Grant another tomb to extend the territory.

Senator Murphy, the Tammany politician, is a fair sample of the Irishmen who attend to our city government. Marks Pasinsky, the buyer from "Tcha-caw-go," with his suffused eye, his high, feminine voice, and his giggle, is familiar enough. The downtown restaurants are full of Pasinskys all the year round. Mozart Rabiner, the salesman, is another old acquaintance. When he has to stop over at a small town where the hotels are poor, Mozart is always the last man in the hotel "'bus." He sees everybody else inside: "After you, sir; after you, madame." Then he takes a place at the back of the 'bus, shining with nobility, and perhaps even holds the door shut. When the 'bus stops before the hotel, Mozart, having been the last man in, is the first man out, dashes to the clerk's desk, and gets the best room. The hotel men know Mozart.

The women's parts are not so well taken as the men's. Miss Louise Dresser plays Ruth Goldman, the costume designer, well; but she has not a long enough perspective on her part, and does not make the most of its possibilities. This part is worth the best the management can do for it. The designer is the heroine of the New York garment trade; she cries out for the novelist or the dramatist who has color enough to paint her romance. For she is a romantic figure. She is the girl who has the cabin de luxe on the French liners, stops at the Élysée Palace Hotel, declares her partiality for "Showpan," and encourages struggling artists.

Potash says of his designer, that she has "the figure of a Venus de Milo and the business head of a Rockefeller." Though she toys with the idea of a romantic life with the Russian musician, she is shrewd enough, in the event, to marry Mawruss Perlmutter and to put the romance into the business.

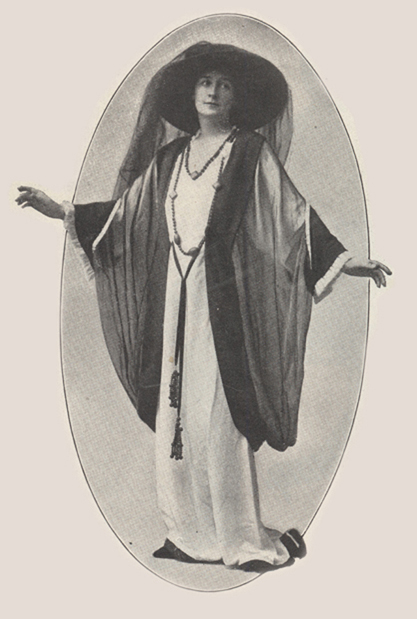

"MISS ROXANE BARTON does an interesting sketch of a very special type of Englishwoman.

Honoria Loue, the president of the Water Color Society. Honoria is an example of the

still hysteria which is the form that 'temperament' seems to take in some Englishwomen"

"MISS ROXANE BARTON does an interesting sketch of a very special type of Englishwoman.

Honoria Loue, the president of the Water Color Society. Honoria is an example of the

still hysteria which is the form that 'temperament' seems to take in some Englishwomen"

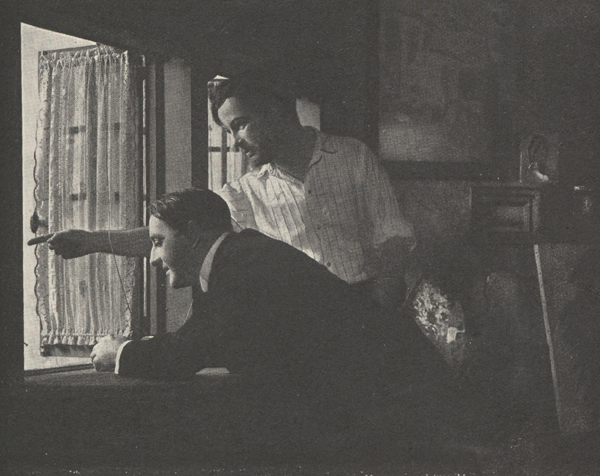

"THERE was an old axiom that no play about an artist could succeed, because the public

would not endure an 'intellectual interest.' 'The Concert' succeeded; therefore we

have three plays about artists now running in New York." The picture shows Leo Ditrichstein

as Jacques Dupont, in "A Temperamental Journey," watching his own funeral procession

"THERE was an old axiom that no play about an artist could succeed, because the public

would not endure an 'intellectual interest.' 'The Concert' succeeded; therefore we

have three plays about artists now running in New York." The picture shows Leo Ditrichstein

as Jacques Dupont, in "A Temperamental Journey," watching his own funeral procession

IT is unfortunate that Mr. Leo Ditrichstein's impersonation in his new play, "The Temperamental Journey," adapted from "Pour Vivre Heureux," should be so reminiscent of the character he made famous in "The Concert." In the new piece he is not a musician, but a young painter who runs away from the world because he can not pay his board bill, and returns after his supposed suicide to find that he has been placed among the modern masters.

Under analysis there is very little alike in the spoiled and petted pianist of "The Concert" and this ingenuous young painter who would never know whether his pictures sold or not, and who would never think of being discouraged if he were not bullied by his fat wife and kicked by every friend and creditor. But externally the two parts have similarities that may give rise to the criticism that Mr. Ditrichstein is repeating himself. The foreign accent is the same in both impersonations, and both the characters have the naïve, inconsequential qualities which the bromidic mind always attributes to artists. Here again Mr. Ditrichstein gives us a sincere and sympathetic piece of acting; but for his own growing popularity it would have been better if, when he at last got out from under his success as Gabor Arany, he could have faced the public in an entirely different sort of character, with lines in which the word "art" did not occur.

Every good play is followed by a host of imitations. There was an old axiom that no

play about an artist could succeed, because the public would not endure an "intellectual interest." "The Concert" succeeded. Therefore we have three plays about artists now

running in New York, and Henrietta Crosman opened her season here by impersonating

an opera singer, said to have been done from Olive Fremstad.

"ARNOLD BENNETT'S 'The Great Adventure' is a piece of good fooling, but on the whole

it is a flimsy thing to come after 'Milestones.' Janet Beecher gives reassuring evidence

of her versatility by her impersonation of the Putney widow, a fresh, comely, sensible

body, who keeps an eye on her reputation, but doesn't care to coddle it"

All the school-teachers up in Vermont are writing plays about the tragedies of genius.

"ARNOLD BENNETT'S 'The Great Adventure' is a piece of good fooling, but on the whole

it is a flimsy thing to come after 'Milestones.' Janet Beecher gives reassuring evidence

of her versatility by her impersonation of the Putney widow, a fresh, comely, sensible

body, who keeps an eye on her reputation, but doesn't care to coddle it"

All the school-teachers up in Vermont are writing plays about the tragedies of genius.

"THE Great Adventure," Mr. Arnold Bennett's dramatization of his playful novel "Buried Alive," was extremely well acted here. All the parts were most fortunately cast. Janet Beecher, who made such a favorable impression as the wife of Gabor Arany in "The Concert," in this play gives us reassuring evidence of her versatility by her impersonation of the Putney widow, who marries the painter under the misapprehension that she is marrying his valet. A fresh, comely, sensible body she makes this young woman, who "keeps an eye on her reputation but doesn't care to coddle it," and her Putney accent seems, to the American ear at least, very well done. Miss Roxane Barton does an interesting sketch of a very special type of Englishwoman, Honoria Loue, the president of the Water Color Society, who comes to gather facts from the supposed valet about the supposedly dead painter. Honoria is an example of the still hysteria which is the form that "temperament" seems to take in some Englishwomen. The play itself is too much a book made over. It scarcely emerges from the novel, and does not improve upon it. The interest lies chiefly in the amusing lines. The last act is one act too many; beyond the incidental interest of the Chicago millionaire, it has little refreshment to offer. The play is a piece of good fooling, but on the whole it is a flimsy thing to come after "Milestones." Mr. Bennett is the unique literary economist of our day, but he may make the roast do three times once too often, and bring down the price of beef. There is a point beyond which an author can not water his stock without hurting the credit of his business.

THE most successful of these artist plays, by box-office accounts, is Haddon Chambers' dramatization of Miss Sedgwick's novel, "Tante." Here again the play does not emerge from the novel, and indeed falls far behind it. The novel is more interesting as a piece of writing than it is as a study of character, or as a story. When Madame Okraska's country place in Cornwall is translated into paint and canvas, we lose the fine sea atmosphere which permeates many pages of the book. Her recital, discussed by the characters of the play, is a pale shadow of Miss Sedgwick's brilliant description of it. Even the Buddha, reduced to a stage property, loses its effectiveness. The thing that gave the novel such vitality and that so engaged the reader's interest was not Karen's wounded faith, nor even the commanding figure of Tante herself, but a certain very definite feeling of Miss Sedgwick's toward Tante. From the first page to the last, the book tingles with this personal feeling. For two thirds of the story the author keeps it under splendid control, and every paragraph is singularly interesting. In the latter chapters of the story, when this feeling takes its head and breaks away from the writer's supple hand, the story becomes dull. This feeling, which is the raison d'être, the body and bones of the book, is distinctly hostile. Miss Sedgwick's relentless accumulation of evidence against Tante has the interest of a detective story, or a story of revenge. Now, this feeling can not be transferred to any character in the play. Even Karen's husband objects to Madame Okraska only when she disturbs the order of his household. So there is no one strong feeling to bind the incidents together; there is nobody here to track Tante down or to get the better of her. She goes about giving herself away in the most unnecessary manner, seeking opportunities to do so.

Aimless though the play is, Tante is a good character part, and Ethel Barrymore is a charming actress; but the two should never have met. Miss Barrymore suggests the part about as much as Mrs. Wharton's Undine Sprague suggests Carreño. She makes the pianist at least fifteen years younger than the Madame Okraska of the novel, looks at one with a frank, handsome, unsuggesting American countenance, and says that she is Polish and Spanish. Miss Barrymore dresses the part conventionally and makes a dashing figure, but she suggests a brand-new wonder from Seattle or Kansas City who would have pictures of herself and her large hats in the musical journals. In "The Concert" Leo Ditrichstein succeeded in making one believe that he was a pianist; but you do not believe it for one instant of Miss Barrymore's Tante. Her impulsive attack upon the piano before the last curtain does not, alas, contribute to the illusion she is trying to produce. Miss Barrymore produces a celebrity, possibly, but her Tante does not suggest one intellectual or temperamental attribute which gives the title character of Miss Sedgwick's novel unquestionable distinction and flavor.