McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 41 (October 1913): 85-95.

TRAINING FOR THE BALLET

Making American Dancers

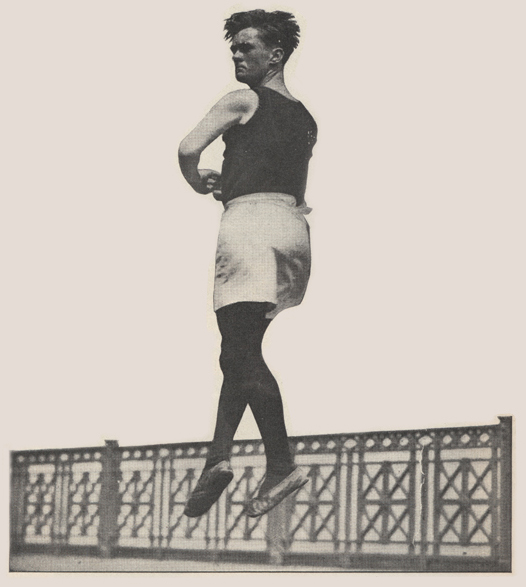

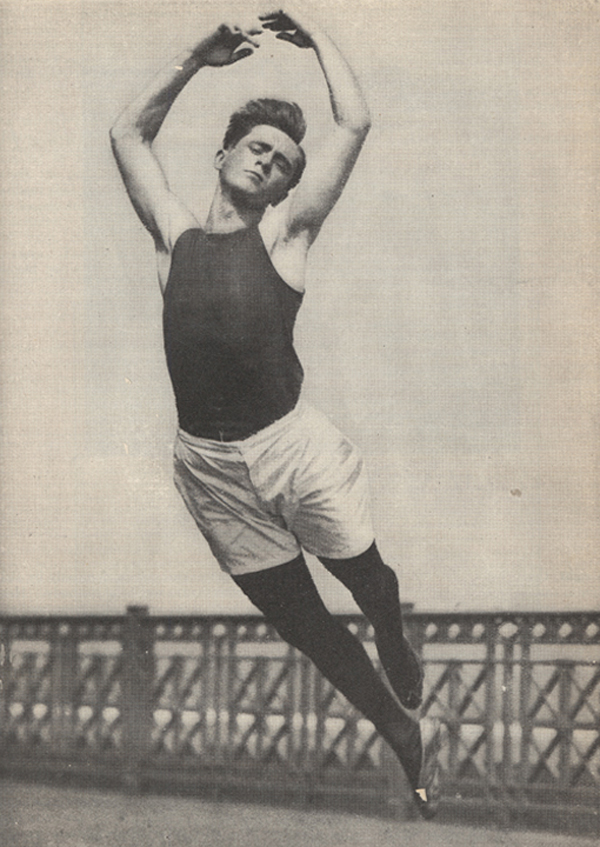

McAULIFFE doing a double turn in the air

McAULIFFE doing a double turn in the air

UNQUESTIONABLY the success of the Russian dancers in this country revived an interest here in dancing as a form of artistic expression. Stage dancing, outside of the opera, has persisted, in America, only in its more vulgar forms: skirt-dancing, high kicking, and the so-called "eccentric" dancing, which is often another name for bad dancing, just as "eccentric" singing might be a euphemism for uncultivated singing. Dancing as a social convention has, of course, nothing to do with dancing as a form of art, and the insipid dancing done in musical comedies has even less. The tendencies of modern music and the supremacy of Wagnerian opera have been an important influence in the decline of the ballet. But, if one watches the street children of New York on any corner where a street piano is playing, one discovers that the raison d'être of dancing as an art still exists; that the original source of it— the creature's enjoyment of its own vitality expressing itself in movement of the body—is still there. And this sense of life, this desire to escape from sordid things and to be a part of the beauty of rhythm, to give vent to some inner experience of delight—or sadness—is, of course, the eternal well-spring of the dance—of folk-dances, of the dance as an art. The great dancer is made, like any other artist, of two things: of a universal human impulse, and a very special and individual experience of it. That this very special experience creates ambition, devotion, very special skill, goes without saying. That is true in any art.

PRACTICE at the bar.—The bar is the foundation of classic dancing. All the beautiful

and intricate figures executed in the ballet are prepared for by this bar-practice,

which the dancer must go through for several hours every day of her life

PRACTICE at the bar.—The bar is the foundation of classic dancing. All the beautiful

and intricate figures executed in the ballet are prepared for by this bar-practice,

which the dancer must go through for several hours every day of her life

IN America we have had no dancers because we have had no schools, and no public that knew good dancing from bad. America has long been the paradise of poor teachers. A man who can do nothing else in the world can teach pretty much anything—and make a living by it—in America. But in nothing has the instruction been poorer than in dancing. Until Dippel and Gatti-Casazza went into the management at the Metropolitan Opera House, not only the premières but the entire corps de ballet were brought over from Europe every year, and this notwithstanding the fact that New York was full of poor girls of every nationality, who were working in sweat-shops and department stores for six dollars a week, while the ballet pays eighteen and twenty.

Four years ago, Herr Dippel and Signor Gatti-Casazza organized the Metropolitan School of Ballet Dancing, to train dancers for the Metropolitan Opera House. The school is under the same business management as the Opera, and until this year the instructor has been Mme. Cavalazzi, the once famous ballerina. Last season there were fifty girls in the school, and this winter the classes will be considerably larger. The instruction in the school is free, with the condition that each girl sign a contract to serve in the Metropolitan ballet for the last three years of her training. The full course is four years. Any girl who desires can make arrangements for individual drill and instruction outside of the regular classes.

After a girl has had one year of instruction, she enters the Metropolitan ballet at $15 a week. The second year she is in the ballet she gets $18 a week, and the third year $20 a week. This winter there will be twenty-four American girls in the Metropolitan ballet, and next winter, 1914- 1915, there will be a full American ballet, for the first time in the history of opera in this country. This winter, also, the première danseuse at the Metropolitan Opera House will be an American girl, Miss Eva Swain, who graduated from the Metropolitan Ballet School in the spring. Miss Swain is typical of the good material that this new school is working into the ballet. Her father is a prosperous New York business man, and his daughter has entered this career with no other instigation than her talent and her love of dancing.

MME. PAULINE VERHOEVEN, the new instructor who succeeds Mme. Cavalazzi, and who took charge of the Metropolitan Ballet School the first of September, says: "When I went to visit the school under Mme. Cavalazzi last spring, I was delighted to find what class of girls were doing the work; intelligent, well-mannered, pretty. Years ago, when I danced as première at the Metropolitan under Mr. Grau's management, all the girls in the ballet were brought from abroad. They had been secured by agents who took whatever they could get, and they were often by no means girls or dancers of the best type. There was little here to attract a girl who had made a good place for herself in her own country. There was no ballet school here then, but there were American girls who were anxious to learn, and I took a few private pupils. From my first experience in teaching them, I saw that American girls had a peculiar aptitude for dancing. In the first place they are strong, and that is a great point. After the first year the work is hard, and the girl must be strong. She must be on the floor for at least two hours every day, and she is working all of that time, using not only her muscles but her mind and her will. After the easy exercises of the first year, there is no mere going through the drill; it is a continual struggle to improve, to get the mastery of one's body little by little. The American girls have, on the whole, better figures than the girls I have seen and worked with in classes abroad. But their chief advantage is that they are not afraid. They have more confidence than French or Italian girls. They suffer no chagrin from making mistakes; they are always ready to try."

Anna Pavlova visited the classes at the Metropolitan Ballet School several years ago, and said afterward that American girls ought to make good dancers "because they are quick and confident, and because, in general, the people here are better nourished than those at home, and the girls have more chance of being strong." There is material to reflect upon in that sentence, as well as suggestions of personal history.

A rapid pirouette

A rapid pirouette

AT the Scala Ballet School, in Milan, the course is nine years, and at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg the course is even longer. But there the pupils are taught music and languages, history and arithmetic, along with their dancing, and their course at the ballet school comprises their whole education. As every one knows, the Russian government, in order to maintain the excellence of its ballet, pensions the dancers after the retiring age, thirty-five. The Imperial Ballet has a boarding school for poor pupils, where forty-eight girls and thirty-four boys live. In addition to these, there are twenty-five girls and twenty boy pupils who are allowed to live at home. Only fifteen or eighteen new pupils are taken into the school every year, and there are always more than a hundred applicants, many of them children of dancers, stage-hands, and people employed about the theaters.

If a girl is going to make dancing her profession, she ought to begin the first exercises when she is nine years old. Small-boned girls are best adapted to the work—trim little girls who are naturally quick in their movements and mentally alert. In watching training classes one notices that the best dancers invariably have bright eyes.

Small women are always best for the ballet. A tall girl looks awkward in the ballet, and her bones are always heavy and slab-like, a weight to carry and hard to manage. Dreamy and lethargic girls are unpromising subjects; the mental response, like the muscular, should be quick and spirited. The work is best done by girls who are quick to feel the demand of the teacher and the appeal of the dance itself, who are easily put on their mettle, and who delight to do their best with every fiber in them. Children who are temperamentally gay and joyous take to it as birds take to flying.

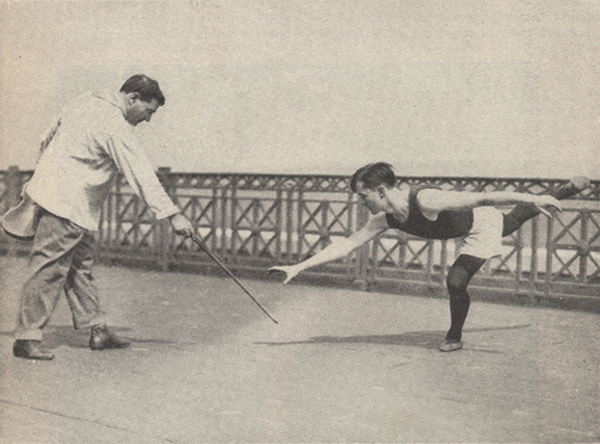

B0Y in fourth arabesque.—McAuliffe is crouching as low as he can on one leg, trying

to touch his teacher's fiddle-bow. His back must form a straight line, parallel with

the floor, and the weight of his body must be so distributed that he lowers and raises

himself of one leg without wabbling and without changing the straight line of his

body

B0Y in fourth arabesque.—McAuliffe is crouching as low as he can on one leg, trying

to touch his teacher's fiddle-bow. His back must form a straight line, parallel with

the floor, and the weight of his body must be so distributed that he lowers and raises

himself of one leg without wabbling and without changing the straight line of his

body

AFTER a year with the simple exercises, the girls begin serious work. They ought not to do much with general gymnasium work, as it loosens the joints too much and makes the legs and arms harder to control. Even experienced dancers have to be careful about the kinds of exercise they permit themselves. Genée says that all exercise, except walking and dancing, puts her in bad form. If the girls have their lesson in the afternoon, they must eat a very light lunch—the less the better. During the two or three hours they are on the floor, they must not drink water at all. Professional dancers, even during a long ballet like "Coppelia," or a dance-drama like "Scheherazade," do not drink water. They sometimes chew a little sponge, or hold iced apollinaris in their mouths without swallowing it.

Every dancing lesson, every professional rehearsal, begins with the work at the horizontal or swinging bar. In every theater or opera house where ballets are given, there must be a practice room with bars. Pavlova and Genée always get to the theater several hours before the performance and do an hour's brisk work at the bar before they go on the stage. All dancers, coryphées and premières alike, go through the bar-practice before going on for their act.

GIRL in fourth arabesque.—The figure can be taken either on the straight leg, as Miss

Luhrs is doing it, or on the bent leg as McAuliffe does it, on the opposite page.

The girl must be able to drop from the air into this position and hold it with absolute

steadiness

GIRL in fourth arabesque.—The figure can be taken either on the straight leg, as Miss

Luhrs is doing it, or on the bent leg as McAuliffe does it, on the opposite page.

The girl must be able to drop from the air into this position and hold it with absolute

steadiness

IN classic dancing there are five positions of the feet, arms, and body, which underlie all dancing; and these are all learned at the bar. They are delightful to watch, but a description of them would be tedious. The principal bar exercises are the various battements and the rond-de-jambe on the floor. The battements —there are many kinds—are all true to their name and consist of various strokes or beats with the leg; throwing the leg out vigorously from the hip, with the ankle stretched so that the joint practically disappears and the whole leg looks as if it had but one bone from hip to toe, and as if that bone were a pliant willow wand. Every suggestion of the angle at the joints must be done away with.

This prepares her for the entrechat, the step in which the dancer springs into the air and touches her feet together, changing them back and forth with lightning strokes before she alights. The girls who are training for premières must learn to do the entrechat four times while they are in the air. Genée often does it six or seven times with perfect ease. This part of dancing, the very bones of technic, can only be acquired under twenty. After that age a dancer can never extend her entrechat, for instance. She can only keep up what she already has. A dancer may go on growing in the grace and poetry of her art, but her technical compass is defined at twenty.

THE bar exercise that is second in importance to the various battements is the rond-de-jambe on the floor, which prepares for the many beautiful kinds of rond-de-jambe in the air, those beautiful circles and semicircles which the dancer describes about her own body with her leg. This movement is practised at the bar by simply keeping the toe of the moving foot on the floor and swinging it back and forth in wide circles.

Not only do Pavlova and Genée and every other dancer practise at the bar before they go on the stage, but they practise exactly the exercises just described. The exercises a dancer does when she is a little girl are the exercises she must keep up until the end of her career. Genée says that if she goes without practice for a week, during a vacation or while she is at sea, it takes her three weeks to get back, and that, when she begins work again, her muscles are so sore that she dreads a vacation. Anna Pavlova keeps up the same indefatigable practice for two or three hours every day. Sometimes, in America, when they are doing short engagements on the road, they use the steam radiator; and they acquiesce in the opinion that this is the only useful end the steam radiator has ever been known to serve.

The most difficult thing the girls have to learn, of course, is toe-dancing. For this, too, they are prepared at the bar. The strength for the toe-work comes from the knee and the instep, but chiefly from the knee. If a girl can make her knee absolutely straight and tense, the instep will usually take care of itself. One often sees newspaper articles about the wonders of a ballet dancer's shoe; how the toe is made of plaster-of-Paris, with a steel support, etc. But a European ballerina only laughs at such a story, takes off her shoe and hands it to you. It is made of kid as soft as glove-kid, except the toe, which is boxed by leather, not nearly so stiff as the heel counter of an ordinary shoe. The toe-dancer needs no support but her own five toes, for it must be remembered that she does not stand on the big toe alone, but evenly on the five.

THERE is an easy kind of toe-dancing, a "fake" performance which we often see generously applauded in musical comedy, in which the dancer stands on her toes instep toward the front. This is not toe-dancing at all, in the proper sense, but a clumsy counterfeit which requires no skill. Any child can be taught to do it in a few months. The only correct position for toe-dancing is with the soles of the feet facing each other. In this position the dancer must be able to walk lightly on her toes to the front of the stage, to pirouette on both toes or on one, to fouette with one leg in the air while she stands on the toe of the other foot, and to do countless other beautiful and graceful things.

It requires long practice to drop from elevation to the toe-tips surely and steadily; and without absolute steadiness a dancer can have no finish. Students during their training can do many of the things, after a fashion, that the most finished dancers do on the stage. The difference is that the students do them waveringly, uncertainly; the ballerina with the sureness and authority with which an accomplished pianist plays his scales.

AT the Century Opera, Signor Luigi Albertieri is training two very talented pupils for premières. Signor Albertieri was for fourteen years ballet-master at the Metropolitan Opera House. He was in his youth a famous dancer in Europe and was a pupil of Cecchetti's afterward the teacher of Pavlova and Nijinski. Signor Albertieri is a remarkable teacher and his training-work this summer was particularly interesting because one of his two advanced pupils was a boy, Edmund McAuliffe, who will be the first American male premier. He has passed his examinations for the High School, but dancing takes so much of his time that he now works at languages with a tutor and studies the piano. McAuliffe's mother studied for the ballet for years, and only the prejudices of her family kept her off the professional stage. The boy loved dancing from the time he could walk, and his mother taught him until he went into Signor Albertieri's class two years ago.

Signor Albertieri's other talented pupil is Genevieve Luhrs, an American girl of thirteen, who was one of the cleverest pupils of Mme. Cavalazzi's school. She is properly built for a dancer; small, light, wiry, with long, straight legs. They both have the faculty of understanding what the instructor means almost before he speaks, and possess the sense of rhythm which must be born in a dancer, and which can never be acquired. Signor Albertieri says: "The legs I can fix, the arms I can fix; but the ear? No, I can not fix. If they have not that, legs and arms are no good."

THE boy and girl need different training and differ in their points of excellence.

The boy, for instance, can not kick so high or so gracefully as the girl. A boy's

hip-bones are longer and his hip-joint less elastic. The boy never practises toe-work,

which in a male dancer would be effeminate. His great point must be his elevation, the distance which he is able to rise in the air, the lightness with which he rises,

and the number of things he can do with his feet while he is in the air. While a girl

première can do the entrechat (change of feet) only four or five times in the air, a man must spring high enough

and manage his feet quickly enough to do it six

THE boy never practises toe-work, which in a male dancer would be effeminate. His

great point must be his elevation, the distance which he is able to rise in the air,

the lightness with which he rises, and the number of things he can do with his feet

while he is in the air

THE boy never practises toe-work, which in a male dancer would be effeminate. His

great point must be his elevation, the distance which he is able to rise in the air,

the lightness with which he rises, and the number of things he can do with his feet

while he is in the air

MME. CAVALAZZI and pupil.—Mme. Cavalazzi was a famous ballerina in her youth. She

has been for four years in charge of the Metropolitan School of Ballet Dancing in

New York, and has just retired. She used sometimes to rouse a careless pupil smartly with her big stick

or eight times before he reaches the floor. Nijinski can do the entrechat ten times with the greatest assurance, and it is said that he has even done it twelve.

MME. CAVALAZZI and pupil.—Mme. Cavalazzi was a famous ballerina in her youth. She

has been for four years in charge of the Metropolitan School of Ballet Dancing in

New York, and has just retired. She used sometimes to rouse a careless pupil smartly with her big stick

or eight times before he reaches the floor. Nijinski can do the entrechat ten times with the greatest assurance, and it is said that he has even done it twelve.

A boy must be able to spring into the air and turn his body round and round as if he were on a pivot. Suspended in the air he must make two, three, four revolutions before he alights. The first picture accompanying this article shows McAuliffe in the second turn in mid-air. The spring is made from the half-foot, by the strong muscles of the knee, toes, and ankle; by catching his breath hard the boy helps his body in the lift. The turns in the air are done by the muscles of the arms and shoulders, which must whirl the whole body around like a coil-spring released.

WITH both the boy and girl balance is an important consideration. The dancer must be able, while standing on the toe or the half-toe of one foot, to execute rapid and difficult figures in the air with the body, the arms, and the other leg, and to be as firm as a rock on this slight support. This can be done only by skilfully distributing the weight of the body. Here a strong back is an important factor, and the muscles of the waist come into play. If the right leg is in the air, the body must bend from the waist toward the lifted leg, away from the left leg which is serving as the support; the right arm, too, is usually stretched parallel with the lifted leg. Balance is well illustrated in the arabesques. These arabesques are in the air, or on one foot with the body in the air, and are often used to end a figure. There are four arabesques in all, but they can be taken in different ways. On page 88 there is a photograph of McAuliffe in the fourth arabesque, crouching as low as he can on one leg; the difficulty here is that he must keep his body on a straight line, parallel with the floor. The bending is done with the muscles of the knee and ankle, and it is exceedingly difficult to distribute the weight of his body so that he shall have no appearance of unsteadiness. The slightest wabble or jerkiness spoils the arabesque entirely. The postures must be taken lightly and easily, or not at all. The trend of the boy's training is to enable him to do things easily and gracefully in the air, and the trend of the girl's is to make her especially proficient in toe-work.

AMERICAN appreciation of dancing has been largely spoiled by the vulgar acrobatic dancing in musical comedies and vaudeville, where the poor girl struggles to make effects without skill or knowledge, always shaking her leg loosely from the hip instead of extending it gracefully. The leg and foot should be graceful, easy, elegant in every movement and posture. The heel and the sole of the foot should be in, toward the dancer's skirt, and to the audience her leg should present one line from knee to toe, without angles. The kick should never lift the foot much above the hip. In the classic dance there is scarcely a "kick" at all; it is an upward stroke of the leg, rather, done altogether from the hip, a graceful placing of the foot in the air. The high-kicking which has disgraced our stage for so long has nothing to do with the ballet. It came from the cabarets of Paris, from the can-can. But there it is not called dancing; it is called kicking.

Mme. Pauline Verhoeven, the new director of the Metropolitan School of Ballet Dancing,

says on this point, "High-kicking is not only ugly and disgusting in itself, but it

is absolutely disastrous to the dancer. She soon becomes so loose at the hip-joint

that she can no longer

A REFRACTORY knee.—Signor Albertieri working with one of his pupils. The knee-joint

must be straight and firm, as the dancer gets from the knee her chief strength in

toe-dancing

control her own motions properly. She injures her joints and muscles for good dancing,

to do something which requires no skill at all. In dancing a girl can not do a figure

at all until she can do it beautifully and gracefully. In Europe we call classic dancing

'noble dancing.' It must have nobility of out line, or it is not dancing at all. The

dancer's art is not to exhibit difficulties, but to conceal them, to make her technic

as light and sure as the motion of a fish in the water or a bird in the air. In Paris

this winter there will be a movement started by the dancers and dancing teachers from

all over the world who met there in August, to reinstate the gavotte, the minuet,

the bergeret, and the pastorale as social dances in France. I only hope the enthusiasm for those beautiful social dances will reach this country and will rout forever the

tango and the turkey-trot. I am to have a class for dancing teachers this winter,

and I shall do my best to make these dances popular."

A REFRACTORY knee.—Signor Albertieri working with one of his pupils. The knee-joint

must be straight and firm, as the dancer gets from the knee her chief strength in

toe-dancing

control her own motions properly. She injures her joints and muscles for good dancing,

to do something which requires no skill at all. In dancing a girl can not do a figure

at all until she can do it beautifully and gracefully. In Europe we call classic dancing

'noble dancing.' It must have nobility of out line, or it is not dancing at all. The

dancer's art is not to exhibit difficulties, but to conceal them, to make her technic

as light and sure as the motion of a fish in the water or a bird in the air. In Paris

this winter there will be a movement started by the dancers and dancing teachers from

all over the world who met there in August, to reinstate the gavotte, the minuet,

the bergeret, and the pastorale as social dances in France. I only hope the enthusiasm for those beautiful social dances will reach this country and will rout forever the

tango and the turkey-trot. I am to have a class for dancing teachers this winter,

and I shall do my best to make these dances popular."

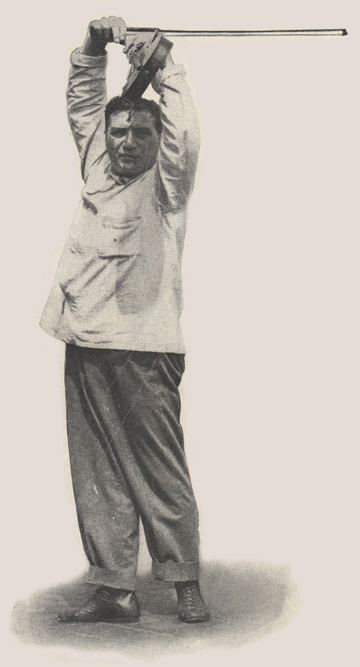

ALBERTIERI encouraging a pupil.—In the rapid exercises in mid-air, and in difficult

figures executed on the toe, the enthusiasm of the teacher is of great help to the

pupil

ALBERTIERI encouraging a pupil.—In the rapid exercises in mid-air, and in difficult

figures executed on the toe, the enthusiasm of the teacher is of great help to the

pupil

CLASSIC dancing, in the sense in which the ballet-masters use the term, must not be confounded with the barefoot "classic" dancing evolved by two American women, Isadora Duncan and Maud Allan. This kind of interpretative dance is for those who like it. I agree with the New York reporter who, in summing up Miss Duncan's dancing of "The Rubaiyat," said that on the whole he preferred Omar's lines to Miss Duncan's.

It is from Russia and nowhere else that the new impulse of the dance has come. There they have taken the classic ballet, mastered it, respected it, given it a new poetry and a new fire. Pavlova always declares that the basic principles of the dance are eternally the same; that only when the dancer has mastered the technic of the classic dance, as taught in the great ballet schools, can she trust herself to "interpret." With her technic perfectly assured, then she may give herself over to imaginative and poetic dancing. But only through that technic can she execute her ideas beautifully or adequately. Even when a dancer is fortunate enough to have a head, she can not get away from her feet.

Posturing and miming are taught at the Imperial Ballet School quite as seriously as dance-steps, and play almost as important a part in the modern Russian dance-drama. It requires years of training to enable the boys to hold the girls while they are whirling and dancing. The art of make-up is elaborately taught, and the examinations in that subject are perhaps more rigid than in anything else. The boy must be able to make-up not only his face but his entire body; he must transform himself into an old man, an Indian, a Chinaman, etc. When Mordkin danced in this country, the stage-hands were greatly amused because he took two hours to paint his body before he went on for the arrow dance. They thought it effeminate business.

PAVLOVA says that she believes the mixture of races in Russia has helped the dancers there and given them more to draw from; that she does not see why the mixture of races here should not in time be seen and felt in dancing. Questioned upon this point, Signor Albertieri said: "Oh, yes! You see a ballet class in Italy, all the girls alike; in France, another kind but all alike. Here you see always variety; red hair with brown eyes, red hair with blue eyes; black hair with fair skin, yellow hair with olive skin. The girls are much prettier and more individual. And they are all right for the legs and quick to learn. But the arms are something terrible! I don't know why it is they can not learn to be alive and graceful with the arms. Their arms mean nothing to them; they are like the arms of a dead woman. Maybe it is that people use their arms more in other countries, and here they are taught to keep them still. You see two washerwomen talking in Italy, and they use their arms all the time, gracefully, very much alive, to express things. Here the arms are like wood. But to dance you must be alive not only in the legs, in the arms also. I think so!"

THE real dancer's practice is beautiful to see, light and rapid, and characterized by a most satisfying elegance

THE real dancer's practice is beautiful to see, light and rapid, and characterized by a most satisfying elegance

The artificial smile that so many dancers wear on the stage is a result of bad training. If the dancer was meant for her work, if she has had the proper practice and enough of it, there need be nothing forced about her smile. She can have herself much more surely in hand than a singer or pianist, and need not be nervous before her audience. Her effort should all have been put forth at another time and place. Unless she can easily do her best, she is not a good dancer. It is only the poor untaught acrobatic dancers of our vaudeville stage who struggle and strain. The real dancer's practice is beautiful to see, light and rapid, and characterized by a most satisfying elegance. When Taglioni went to London for the first time, her father, who was her teacher, had a wooden platform erected in their lodgings for the girl to practise upon. The gentleman who occupied the rooms below sent up word that the young dancer was on no account to modify her practice through fear of disturbing him. "Tell the gentleman," exclaimed the indignant father, "that I, her father, have never heard my daughter's step!"