McClure's Magazine

From McClure's Magazine, 44 (January 1915): 17-28.

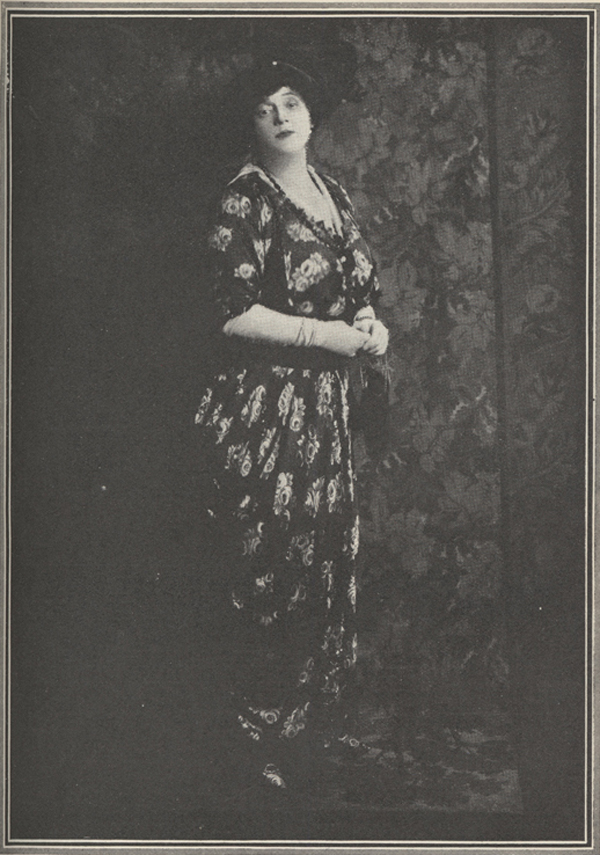

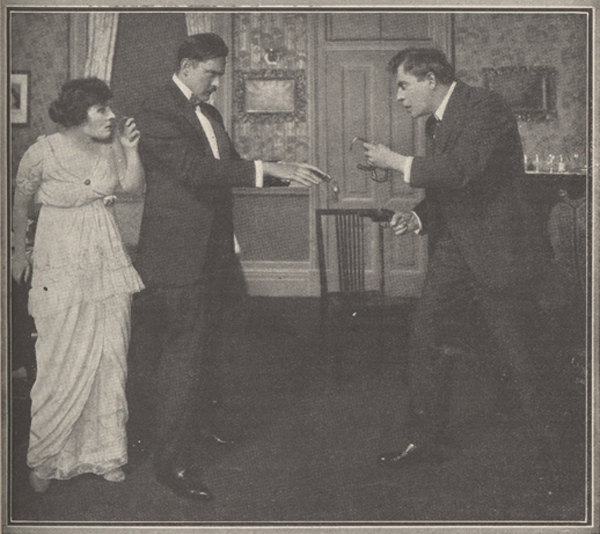

From "TWIN BEDS"

From "TWIN BEDS"

THE SWEATED DRAMA

AUTHOR OF "O PIONEERS!" "THE BOHEMIAN GIRI," "THREE AMERICAN SINGERS," ETC.IT is not often that one reads a piece of criticism with as keen an edge as this, with so direct and fearless and unconventional a point of view. In discussing what makes a play succeed in New York—what qualities it must have to satisfy the alert mercurial intelligence of a Broadway crowd—the writer anticipates some of the questions that will arise when the successful new plays of this season go out to meet the verdict of the country

THE difference between a play that succeeds because it is alive, and a play that "goes" because it has been galvanized into a jerky activity by the producer and stage-manager, is readily felt, but difficult to define. Among many of our older theater-goers there is even a preference for the safe machine-made play, which can always be counted upon to work out certain dramatic situations according to rule, like the adaptations of French plays that were annually offered to the public by New York managers thirty years ago. From the younger public, however, there is a swelling demand for plays with a strong element of contemporaneousness. Any one who watches New York audiences closely will see that people like plays not only about their own time, but plays that deal with their own social environment, written in the speech and idiom of their own class. "A Pair of Silk Stockings," the well dressed, urbane, and charmingly enacted comedy with which Mr. Winthrop Ames opened the Little Theater this season, was so much in the tone of the audience it pleased that one could scarcely tell on which side of the footlights one happened to be sitting. During the long run of "Potash and Perlmutter" here, we learned as much about the garment trade in New York from the very characteristic audiences as from the play. Far from dissenting or disapproving, the great Jewish population of the city packed Cohan's Theater night after night, roared at and applauded the play, greedily appropriated it, fairly ate it up. "Within the Law," during its two years' run, drew its audiences from every class and condition; but the prevailing complexion of the house was always the same—so much so that it seemed as if all the working-girls in New York were to be found in the Eltinge Theater every night. They were a feature of each performance, commented with authority, and their applause was personal. The supposition that what a shop-girl likes is a play about a duchess may be true in sleepier countries; but in New York she likes a play about a shop-girl who "gets hers back."

Each season brings its crop of machine-made plays, patched together to meet the requirements of a certain manager or actor or theater. They are usually echoes of last season's successes, made with the producer standing at the playwright's elbow, pointing out to him the sure thing. These plays run for a while on the interest created by the play they echo, and because they have been galvanized by an effective stage management, just as the street toy-seller's tin mice and spiders run for a while about the sidewalk. But this perfunctory continuance has little in common with the career of a play that, from the first night, walks off on its own feet.

The dramatist is a much more important factor in our theater than he was fifteen years ago, and he must be a much abler and more inventive man. People will still go to see a well beloved actor in an indifferent play; but the interest in good plays is much livelier in New York to-day than the interest in good actors. No actor, to-day, could repeat Richard Mansfield's successes with plays adapted and translated from hither-and-yon. In New York, at least, there is now such a thing as a play sense, and the plays make the actors. The live new play, indeed, can not be so very poorly acted. The actor is pitted against a wide-awake, biting sort of criticism from the people who are in front of him. To get such a vehement response as the two principal actors got every night in "Potash and Perlmutter," they had to play the Jewish partners well, and superlatively well. They might have fooled people about a French count or a German baron, but they could not fool that audience about Abe and Mawruss.

That cordial and yet critical relation between the actor and the audience, that enthusiasm for a correct shade or intonation, makes a play as real as a ball game or a tenement fire. Such a vital interest has little in common with the mild consent with which people sit by and watch Cyril Maude's pleasant impersonation of "Grumpy" or Mr. Faversham's energetic acting in his new French play, "The Hawk." In the one instance, the audience is being entertained. In the other, the audience is working with the actors and the playwright toward the making of American plays, as it works with the league and makes a national game. The new play that has anything interesting to say about New York life is met with a roar, and continued amid a struggle for seats. The public makes no demand; the good play makes the demand.

"Potash and Perlmutter," the play version, was put together carelessly enough—very rough sort of carpentry. The plot did not matter, and nobody considered it. Mr. Montague Glass's characters were not counterfeits. In the beginning he had contributed a vital idea. This play and many of the plays produced at Cohan's Theater were built upon the theory that people are more interested in character types and in live lines than in situations.

A New Cut in "Crook" Plays

Ever since the long run of "Within the Law," we have been surfeited with "crook"

PYGMALION

In the second act Eliza (Mrs. Campbell), midway in her transformation from a Cockney

flower-girl to a duchess, walks on, beautifully dressed, and with an irreproachable

accent relates anecdotes from her family history that electrify her hearers—a gathering

of fashionable London society. So irresistible is the beauty and distinction of her

appearance, so exquisite her intonation, that such expressions as "on the burst" and

"they done her in" are accepted by her astonished companions as the newest small talk

PYGMALION

In the second act Eliza (Mrs. Campbell), midway in her transformation from a Cockney

flower-girl to a duchess, walks on, beautifully dressed, and with an irreproachable

accent relates anecdotes from her family history that electrify her hearers—a gathering

of fashionable London society. So irresistible is the beauty and distinction of her

appearance, so exquisite her intonation, that such expressions as "on the burst" and

"they done her in" are accepted by her astonished companions as the newest small talk

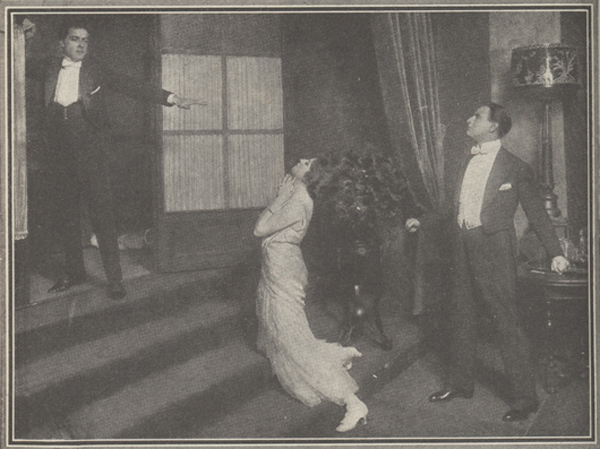

THE HAWK

Not even Mr. Faversham's forceful and unaffected acting can make the sentiment of

this scene, where the husband leaves his wife to her lover and her fate, seem other

than old-fashioned. His parting speech, with its eloquent denunciation and sonorous

periods, has the unalterable cut of other times and other manners in play-making

play; and even before there was no dearth of this kind of melodrama. Machine-made

and perfunctory plays about crime will always meet with success, but man-made plays

will always meet with greater success. Mr. Reizenstein's play, "On Trial," is a purely

conventional crook play which interests its audience by a novel turn in its presentation.

The story is told backwards. The play opens in a court-room, just as the jury is being sworn in. The audience is made acquainted with the outline of the plot in the statement of the prosecuting attorney. The wife of the murdered capitalist takes the stand, and is asked to relate

the circumstances that preceded the murder. The stage then goes dark for a few seconds,

and the matter of her testimony is given in dramatic form—the scene of the murder and the marital quarrel that preceded

it being played out in full. The second act also opens in the courtroom. The child of the man accused of the murder is put on the stand, and is asked to

give an account of what happened in the home of the accused on the night of the murder.

Again the stage flashes dark, and the evidence is played out before the audience.

The third act deals in a similar way with the wife of the accused and her testimony. The story is so bald and time-worn that it might be used in vaudeville as a parody

upon a too familiar type of melodrama. But the device of the continuous court-room operations, done with a good deal of

verisimilitude, is novel, and carries the cheap story across. The audience goes to

hear the mock murder trial, not the conventional story revealed by it.

THE HAWK

Not even Mr. Faversham's forceful and unaffected acting can make the sentiment of

this scene, where the husband leaves his wife to her lover and her fate, seem other

than old-fashioned. His parting speech, with its eloquent denunciation and sonorous

periods, has the unalterable cut of other times and other manners in play-making

play; and even before there was no dearth of this kind of melodrama. Machine-made

and perfunctory plays about crime will always meet with success, but man-made plays

will always meet with greater success. Mr. Reizenstein's play, "On Trial," is a purely

conventional crook play which interests its audience by a novel turn in its presentation.

The story is told backwards. The play opens in a court-room, just as the jury is being sworn in. The audience is made acquainted with the outline of the plot in the statement of the prosecuting attorney. The wife of the murdered capitalist takes the stand, and is asked to relate

the circumstances that preceded the murder. The stage then goes dark for a few seconds,

and the matter of her testimony is given in dramatic form—the scene of the murder and the marital quarrel that preceded

it being played out in full. The second act also opens in the courtroom. The child of the man accused of the murder is put on the stand, and is asked to

give an account of what happened in the home of the accused on the night of the murder.

Again the stage flashes dark, and the evidence is played out before the audience.

The third act deals in a similar way with the wife of the accused and her testimony. The story is so bald and time-worn that it might be used in vaudeville as a parody

upon a too familiar type of melodrama. But the device of the continuous court-room operations, done with a good deal of

verisimilitude, is novel, and carries the cheap story across. The audience goes to

hear the mock murder trial, not the conventional story revealed by it.

The play is the work of a very young man who has studied for the bar, and he has turned

his legal terminology and his sense of the dramatic interest inherent in all such

trials to such good account that he

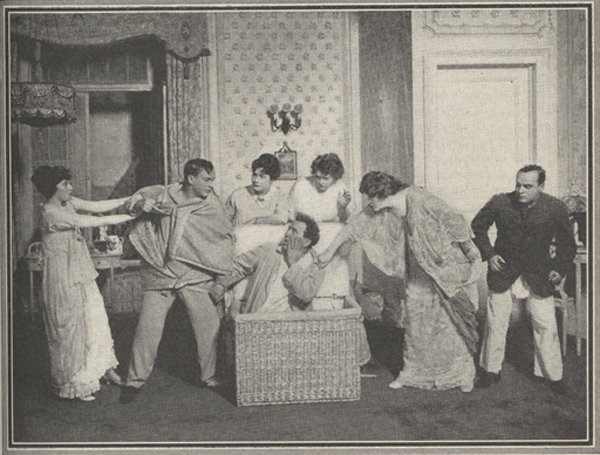

TWIN BEDS

The dénouement, where the Italian tenor, after being relentlessly hunted through two

acts by the unfortunate consequences of having, while tipsy, got into the wrong apartment

and the wrong twin bed, is discovered shivering in the clothes-basket, clad in the

rightful husband's bath-robe. His spirit is so broken as to disarm every one except

his Amazonian Brooklyn wife

must certainly have some facility in theatrical manipulation. His characters, however, are as bromidic and uninteresting as are their lines, and he seems a good deal indebted

to the methods used in moving-picture shows for his back-and-forth presentation.

TWIN BEDS

The dénouement, where the Italian tenor, after being relentlessly hunted through two

acts by the unfortunate consequences of having, while tipsy, got into the wrong apartment

and the wrong twin bed, is discovered shivering in the clothes-basket, clad in the

rightful husband's bath-robe. His spirit is so broken as to disarm every one except

his Amazonian Brooklyn wife

must certainly have some facility in theatrical manipulation. His characters, however, are as bromidic and uninteresting as are their lines, and he seems a good deal indebted

to the methods used in moving-picture shows for his back-and-forth presentation.

A "Crook" Play that is a Live Wire

On the other hand, Mr. Willard Mack, the actor, came to the writing of his play, "Kick In," with a fresh interest and a keen personal sympathy. For the very reason that the crook play is a theatrical staple,—the demand for it is as steady as the demand for soap or butter,—the slightest freshness of attack, the least liveliness of invention in such a play, is always generously rewarded. The appeal of Mr. Bayard Veiller's first act and his sympathetic presentation of his little shop-girl, in his play "Within the Law," made a cordial public overlook some of the flimsy construction in the latter part, where his own interest certainly flagged. Except for a disreputably poor last act, "Kick In" is a better play than "Within the Law." The author's spurt lasted longer; the play is closer knit, more consequential and probable. Here we have, not one girl, but a whole group of characters who are strongly individualized and who have a direct human appeal. The strongest interest of the play lies, not in the police machinery, but in these very real and human people whose fortunes are taken up at a critical moment.

Chick Hewes, the hero of the play, is, in the language of the police department, a "high-brow crook"—an attractive young fellow who wanted more of the good things offered for sale in a big city than his earning power could command. He forged, served his sentence in prison, came out of Sing Sing, got a job, married a girl who is honest, intelligent, and interesting, and is living straight. The only thing the police have against him is that he will not turn a cold shoulder on several suspicious characters who befriended him when he first came out of prison.

When the play opens, an Italian boy, Bennie, who was Chick's cell-mate in Sing Sing, has blown a safe in Harlem and stolen a diamond necklace. Bennie was shot while getting away, and sought refuge with his sweetheart, who brings him, mortally wounded, in a taxi-cab to Chick and Molly Hewes. They take him in and hide him in the garret of the boarding-house in which they live. The ltalian dies there, and the necessity of disposing of his body brings Chick and Molly, their Irish landlady, and Molly's dope-eating brother under the suspicion of the police. The fortunes of this group of people are followed so sympathetically and intelligently that the piece has a fresh, human quality rare in plays of this order.

John Barrymore as the "High-brow Crook"

The figure of Chick Hewes is interesting per se—would be interesting in any play, quite aside from handcuffs and revolvers and safe-crackers' slang. He could walk into a delicately shaded water-color piece like "A Pair of Silk Stockings," and be quite as real a person as he is in the melodrama. The character is cleanly and firmly drawn. The author and Mr. John Barrymore, who plays the part, have so happily combined to make this character what it is, that it is hard to say how much of the result is due to either. But the result is absolutely convincing—a first-hand, sincere piece of character work. It is like a vigorous, suggestive drawing of a human face, while the men in "On Trial" are like worn-out newspaper cuts, only human in that they follow general anatomical and emotional outlines.

The play runs along rapidly, the four acts falling within forty-eight hours, and having to do with nothing but the disposal of Bennie's body and of the diamond necklace he stole. Under such circumstances one becomes pretty well acquainted with all the characters concerned, a group of people lifted out of the many little and big worlds which New York holds. The author breaks through a wall and lets his audience look in on a particular kind of life: on the rooms that are kept up and the clothes that are paid for on a salary of twenty-five dollars a week; on two young people, still in love with each other, who have been made to think and feel by the many-shaded life of a great city made up of so many races and passions.

Familiar New York Types Made to Tell on the Stage

The woman is the more intelligent of the two. She has learned a great deal along the hard roads of New York, under the shadow of police suspicion, with a hot-headed husband and a drug-debauched brother to look out for. Moreover, all the Hewes' friends are interesting. There is a retired shop-lifter with a luxurious Southern accent, who brightens the scene by her costumes and vocabulary. The Irish landlady (whose house and reputation are so imperiled by Chick's rashness and by Bennie's "croaking" in her garret) is of a fine, vigorous type gratefully remembered by many a young man who has known hard times in New York; while her perfectly worthless daughter, Daisy, who retired from the duties of a cash-girl and wants to be a cabaret singer, is absolutely representative. Is there, from Washington Square to Harlem, an industrious, self-respecting landlady or janitress who is not cursed with just such a lazy, dawdling, evening-paper graduate for a daughter?

When an author has brought a group of characters up to the temperature of the human

body, presenting them fairly as wanting the agreeable things of life that we all want,

and trying to keep out from under poverty and police stupidity and auto-trucks and

all the insensate machinery of a great metropolis, he has no need of argument or big speeches. The situation is in itself compelling, and human beings take the

part of human beings. Even the tough little pavement girl, Bennie's sweetheart, who

follows the lure of Italy into the North River and drowns herself in the water where

her dago's trouble-making body has been dumped out of a barrel a few hours before,

has the whole sympathy of the audience. Her stony stare at the ceiling, after Chick has carried Bennie's corpse down from

the floor above, brings the scene in

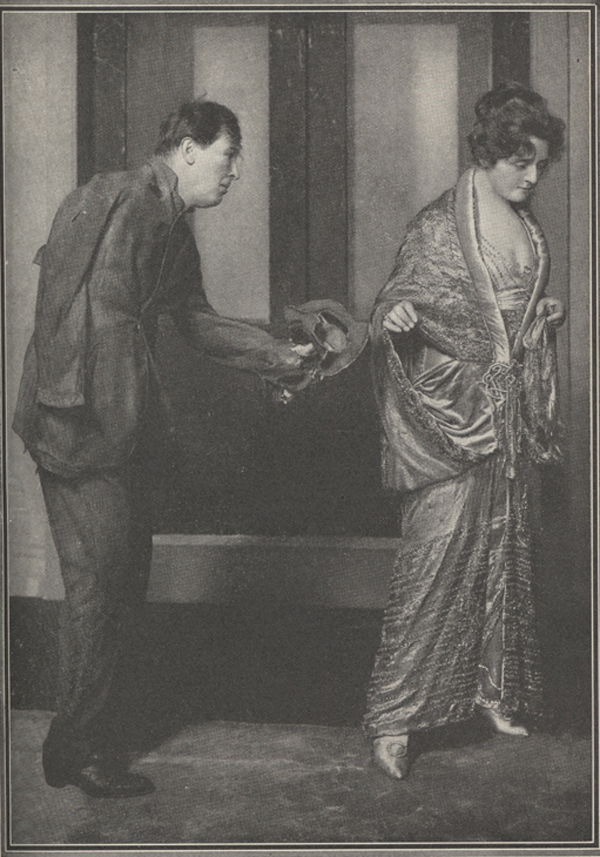

THE PHANTOM RIVAL

The brief scene between the vagabond and the woman he once loved is the one really

poignant and moving passage in what is, on the whole, a singularly uninspired production.

Into his impersonation of the one-armed tramp—a wonderfully effective piece of make-up—Leo

Ditrichstein puts some of his finest acting

the attic uncomfortably near; and Chick's appearance when he comes back from this

grisly job is a credit to Mr. Barrymore's intelligence and talent.

THE PHANTOM RIVAL

The brief scene between the vagabond and the woman he once loved is the one really

poignant and moving passage in what is, on the whole, a singularly uninspired production.

Into his impersonation of the one-armed tramp—a wonderfully effective piece of make-up—Leo

Ditrichstein puts some of his finest acting

the attic uncomfortably near; and Chick's appearance when he comes back from this

grisly job is a credit to Mr. Barrymore's intelligence and talent.

The last act is such a disappointment that it is better to remember the play as concluding in the Hewes' rooms, with the really thrilling struggle between Chick and the thug from the police office—the best stage fight put on here in years. No low lights and shuffling about it. The curtain creates an electric storm in the audience. The suspense must last for ten or twelve minutes, and the actors are driven at lightning speed as new ideas and complications and novel weapons flash into the action. In all this excitement, neither Miss Grey nor Mr. Barrymore lose their heads or their taste for a second—not a tone too high, not a word too much. ln the hands of a pair of bunglers the scene would be ridiculous.

The Comedy of the Human Hive

Another New York play with plenty of movement is "Twin Beds," by Salisbury Field and Margaret Mayo—made up of popular types and manners, popular diversions, and popular furniture. This farce has the unusual merit of a last act with something to say, says it vociferously, and, when it is out of breath, stops. The complications arise from the similarity of the suites in New York apartment-houses, and the dissimilarity of the people who are packed into these human hives and made neighbors by a bond no more personal than a lease. Though unpretentious, it has a great deal more substance and spirit than many so-called serious plays that have been written about New York life—than "Fine Feathers," for instance. The humor does not entirely depend upon mistakes and misunderstandings; and the first act, in which there are no "beds" at all, is quite as interesting as the second and third. The lines are spontaneous and amusing, and the seven characters are most engaging people, and are sketched in with a spirited hand. The Italian tenor,—who comes tipsy into the wrong apartment, and, reassured by the familiar wall-paper and furniture, gets into quite the wrong twin bed,—his Amazonian Brooklyn wife, the irascible Harry Hawkins and his Blanche, are all people sufficiently interesting in themselves aside from the elements of farce.

The Tenor in the Clothes-Basket

In the third act all the old devices of farce—old as "The Merry Wives of Windsor"—are used with perfectly plausible appropriateness. The tenor sleeps peacefully all night in the wrong bed, and peeps innocently out over the coverlid at the wrong wife in the morning. Before he woke, the new maid carried off his clothes to be pressed. The rightful husband of the apartment returns, and then the game begins—the tenor jumping into the clothes-basket, hiding in the closet and under the bed, as the unconscious husband comes and goes. The tenor is, of course, terribly afraid of taking cold, and every time that he emerges shivering from one of his hiding-places he gives a pathetic little bleat and tries his voice to see whether it is still with him. His innocent efforts to get some clothes on and go home are continually frustrated until his storming wife, the heavy-weight Signora, bursts into the apartment and finds her "Bluebird" in the clothes-basket, still unclad and still trying to do the best he can under the circumstances. The Signora is permitted pointed remarks at times, but the tenor himself is as modest as a flower and behaves rather like a discreet fat rabbit. Besides its neat application of the old laugh-provoking methods of farce, "Twin Beds" has a zest of its own. An ounce of spirit in the playwright is worth pounds of wisdom and sagacity in the producer.

Ditrichstein a "Phantom Rival" to Himself

These States are so many and so big that we have as many grades of audience as there are kinds of plays. Mr. Leo Ditrichstein, known everywhere for his unique success in "The Concert," this year appears in his own version of a play by Ferenc Molnar which he calls "The Phantom Rival." Despite the opening scene in the restaurant of an uptown hotel and the appeal of food well served upon the stage,—Mr. Ditrichstein never fails to tempt his audience by appetizing food,—the play is poorly transplanted. A jealous husband (there are none in New York—it was not so to be) is to take his wife to a ball, where he wishes her to make herself agreeable to the Russian Ambassador, with whom he is putting through an underground railway franchise for "Petrograd." She discovers that at the ball she will meet a young Russian who was once her suitor, and who left New York twelve years before, promising to return—perhaps as a great general or statesman, perhaps as an artist (he sang well), perhaps as a failure. The playwright's argument is that every husband has such a shadowy rival, an earlier suitor whom the wife idealizes and to whom she offers the flowers of fancy, while she has to do with her husband only about the soup and roast. This lady, Mrs. Marshall, lies down to rest before dressing for the ball, and the scenes that immediately follow occur, as the play-bill states, "in Mrs. Marshall's mind," a most unpropitious place for any scene to occur.

KICK IN

The scene in the third act, where, after the best stage fight put on in years,—a fight

that fairly lifts the audience out of their seats,—Chick Hewes (John Barrymore), the

"high-brow crook," holds out his hands for the handcuffs

KICK IN

The scene in the third act, where, after the best stage fight put on in years,—a fight

that fairly lifts the audience out of their seats,—Chick Hewes (John Barrymore), the

"high-brow crook," holds out his hands for the handcuffs

She dreams that she goes to the ball and meets her former admirer, first as a victorious general, then as the Russian Prime Minister, then as an Italian tenor, and finally as a one-armed tramp. Any one can see what an opportunity these dreams would give for wit, sentiment, true romance, if only the lady were a lady, and if the playwright had the imagination of, say, a Mr. Barrie. But Mrs. Marshall's ideals, released by sleep, prove to be a boil-down of the trashiest sort of fiction. Compared to Mrs. Marshall's, the mind of Florence Barclay is austere. The lady's behavior, in her dreams, is shameless, and her speeches are more so. Unless Mr. Ditrichstein is a mordant woman-hater, the lines he has to utter as the General and the Prime Minister must cost him an effort. As the tenor he is more amusing, and as the tramp he is really moving. No doubt, in each consenting audience that witnesses the play, there are women with ideas quite as silly as Mrs. Marshall's; but there are minds too slushy and anemic and generally mendacious to be thus visualized upon the stage. The same people who packed the house for "Everywoman," and who were deeply gratified to see the tightly corseted heroine throw a bottle of champagne through a mirror, will enjoy the equally bald suggestion of "The Phantom Rival"; but this is not at all the same public that Mr. Ditrichstein has formerly interested. Few of the admirers of his happier ventures will accompany him on his wanderings through the sachet-scented untidiness of Mrs. Marshall's sickly brain.

"Under Cover" is undoubtedly the best of the purely machine-made plays now running in New York. The subject (the mysterious operations of the New York customs in pursuit of a pearl necklace smuggled through the port) is a popular one, and the stage-hands, the lights, the revolvers, and the galvanic battery are driven hard. This play a dozen times outnumbers "Kick In" in tricks, situations, combinations, but entirely lacks the power to produce that warmer kind of excitement which the other play easily provokes by its human appeal. Nobody would ever want to see "Under Cover" twice, while "Kick In" goes well a second or even a third time. One grows attached to the people in it, as many people grew to feel a personal interest in the heroine of "Within the Law." These "Under Cover" people are as unattractive a lot as ever an audience was called upon to spend a few hours with. Such a picture of life and manners in the houses of "prominent" people would startle a mild man from Montana. However, in New York the term "society" is as broad as ethnology. The author seems to think it entirely probable that a "society girl" will make love to a smuggler, and at the same time burglarize his sleeping apartments to oblige the custom officers and keep her sister from paying the penalty for swindling.

Since he is playing with a bag of tricks, the author has had spirit enough to play a trick or two of his own, and he gets his best effect by "keeping a secret from the audience," which we have always been told was the gravest technical sin a dramatist could commit. The hypothetical audience that will not endure such reticence, counts for very little against a very large ticket-buying audience that heartily enjoys it.

A Versatile Young Playwright

Roi Cooper Megrue, the author of "Under Cover," is evidently a versatile man, and he is represented in New York this winter by a much better play than the one just mentioned. He and Walter Hackett are the authors of "It Pays to Advertise," the clever farce now running at Cohan's Theater. Cohan's Theater has become a guaranty of a certain sort of liveliness, and the new farce follows the animated tradition of the house. The play works out an idea, and depends for its interest upon something more gratifying than a succession of mechanical devices. The son of a soap king falls in love with his father's secretary, is kicked out to struggle for himself, goes into soap on his own account, and, with the help of the secretary and a remarkable press agent, works up such a business that his father is compelled to take him into the trust. The play deals with the New York business world, its methods and standards, its philosophy and slang. It presents well known and always amusing New York types, and is full of shrewd observation and pithy lines. In short, it is the sort of play that New York drinks up like a thirsty desert.

Like most of our successful comedies, and like all plays given at Cohan's, this farce captures its public largely through its garniture of slang, its repetition and variations of the racy turns of speech that one hears in New York every day in the year. We go to the theater to hear the humor of epithet and similitude, quite as often as we go to hear a story told. Elizabethan audiences were not more interested in the flexibility of their language, in the preposterous stretching of words, than is the Broadway audience of 1914-15. The playwright of to-day must specialize in the rapidly changing, picturesque speech of the particular world he depicts. That we call this juggling with words "slang" is no matter. It is the living speech in which millions of people carry on the business and social operations of life, and it is a really creative force in language. In our plays, words speak louder than actions—and they have a much more individual flavor.

The New York streets would offer a tempting field to a human botanist like the Professor in Mr. Shaw's "Pygmalion." When English people go to hear an American play, they go to hear the slang, our most original contribution to the stage. "Potash and Perlmutter" drew a curiously "high-brow" audience in London. It is scarcely too much to say that slang is the one really literary element in our plays. In this respect the playwright is held up to a standard. His epithets must equal in aptness and flavor the every-day speech of the people who sit and watch his play. And he can not go to sleep. He can no more sell them last year's slang than he could sell them last year's models. His phrases must have the new cut. Not since Shakespeare's time has there been anything like this popular demand for variety and color in language. The man who writes popular plays has got to produce the goods, linguistically. He must hunt for phrases like a poet, scour the streets, the factories, the bars, the park benches for turns of speech, and write in an unprinted language. This avidity of the public for color and character in the lines, coupled with their eagerness to see plays about themselves and the life they are now living, give our dramatists their greatest opportunity.

The "Dope" the Public Wants

When a company of old-fashioned actors and producers get together and the talk runs on play-making, it usually takes the form of a discussion of rule-of-thumb devices: which trick will work here and which will work there; when the audience must be kept in the dark and when it may safely be enlightened—as if the audience were an irresponsible lunatic that had to be lured from one padded cell into another. While the mechanics of emotion may be counted upon to produce certain effects, bigger effects are accomplished by not taking them into account at all. The veteran producer advises the young dramatist to "give them a little of this dope" and a little of that; but the real, the sovereign dope—ideas, convictions, something to say—he gives no advice about. All the managerial formulas and recipes have their value, but a live idea outweighs all of them. Robust invention can walk out in its pajamas, without one of these blessed amulets upon its person, and be sure of a fighting chance. The plays that have made the most noise, if not the most money, in the last five years, have been plays which brazenly disregarded the traditions of play-making. One has only to sit through a play made on the old pattern, like "The Hawk," or the revival of that splendid old play "Diplomacy"—so admirably acted by William Gillette, Leslie Faber, Marie Doro, and Blanche Bates—to realize that for this public at this time there is more to be got out of the crude new plays than out of the best of the old ones. The editing-out of asides and the insertion of lines about motor-cars, does not modernize an old play. The measure, the accent, the whole conception of life and the theater, are different. The revivals here of "Lady Windermere's Fan" and "A Scrap of Paper," last spring, pointed to the same thing. Such revivals must be given for their quaintness, for their difference purely; and they are most effective played in the spirit and costumes and conventions of the time in which they were written.

Who Will Follow Fanny?

The American playwright to-day has a free field in so far as the public is concerned. He may do all that becomes a man, even be candid. He does not have to confine himself to sentimentality, if he has something vigorous to take its place. He may write for any sort of public toward which his invention leads him, for we have here every sort of public. We have a public for "It Pays to Advertise," and we had a public— a most enthusiastic one—for Galsworthy's beautiful little play, "The Pigeon." The success of "Fanny's First Play" here proved that we have even a public which—with the proper tip—will sit by and see a whole play devoted to the ridiculing of dramatic conventions, to fighting old ideas of technique. We will laugh— sometimes uncertainly—when these hallowed precepts about keeping and losing the sympathies of the audience are taken up one after another and kicked downstairs. What an encouragement to young playwrights to go at the matter as freshly as Fanny did! You can, if you are clever enough, defy the laws of the drama, and make a play about nothing but human nature, that will still pack houses. Mr. Shaw's contempt for the conventions of play-making are responsible for a good deal of the energy and much of the wilful eccentricity of his plays. Irritated and bored by years of dramatic criticism, he began to make fun of these rules for the distribution of moral qualities and sentiment, which every play was supposed to follow. He began to make plays about people as inconsistent as the people he knew—lovely heroines with bad tempers, exemplary wives who were in love with two men at the same time. A part of the public, at least,—and a sufficient part of it,—left its padded cell and its continuous bath of soothing platitudes quite willingly, and seemed rationally amused by the liberties Mr. Shaw took with it.

One of the foremost English dramatic critics, who often comes to New York, says that whenever he comes he sees interesting plays here, plays that seem promising; but the discouraging thing about them is that they are never by the same men who brought out promising plays a few seasons before. The promising young men do not go forward, they go backward. This must result from over-cordiality on the part of our public, and especially of our managers. Their eagerness to bring a young playwright into his own has resulted in a forcing system. They give a young man of talent no time to learn anything or to feel his way. They will take his worst, and just as much of it as he can give them. Not being an idealist, he gets no better. He is too busy selling what he has in his head to get anything more. There are some things that have to come home in the dark, or they never come. As soon as our managers get a tip that there is "something" in a young man, they grow ravenous. They phlebotomize, trephine, disembowel him, and then have to turn to the unripe product of a newer man. The playwright who wants to amount to anything has got to take care of his own head.