The Home Monthly

From The Home Monthly, 6 (January 1897): 11.

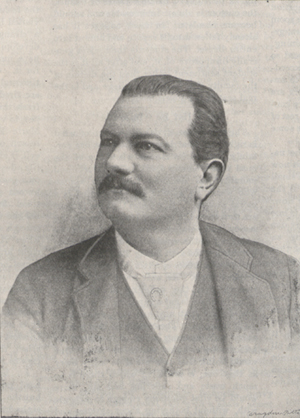

Italo Campanini.

ITALO CAMPANINO, who died recently at his home in Parma, Italy, was probably the greatest of all the operatic tenors of his time. When he was a very young lad he served in Garibaldi's army and it was in the camp, singing the patriotic songs of New Italy, that he first learned the power of his voice. After the war was over he studied at Parma and later under Lamperti at Milan. He sang with little success until he made his debut as Faust in Milan, when he was at once recognized as one of the greatest tenors of his time.

Campanini's history, when it is written, will read like a fairy tale, or more properly

like the fable of the improvident grasshopper. Time was, in the days when he sang

most perfectly, when he was called the Prince of Song, the Knave of Hearts, Italo

the Magnificent, and many titles quite as euphuistic. Few people who had the pleasure

of witnessing it will ever forget that first American production of "Aida" by the

Mapleson Opera Company with Campanini as Rhademes, or that magnificent scene in which he was borne in on a shield resting on the shoulders

of six Abyssinian slaves, clad in golden armour, naked sword in hand like a statue

of Victory, while a chorus of six hundred priests and soldiers sang the great triumphal

march to the accompaniment of golden trumpets. He had money enough then, so much that

he could scarcely devise ways to spend it, so his friends obligingly spent it for

him. But the great bulk of his fortune was lost on the first American production of

"Othello." He brought out the opera himself with all due magnificence. There

ITALO CAMPANINI.

was an Othello indeed, and he sang that famous love aria at the end of the second act as no one

has sung it since, not even Tomagno. When he dragged Desdemona about by the hair of

her head, the matinee girls used to say they envied her.

ITALO CAMPANINI.

was an Othello indeed, and he sang that famous love aria at the end of the second act as no one

has sung it since, not even Tomagno. When he dragged Desdemona about by the hair of

her head, the matinee girls used to say they envied her.

But Verdi's "Othello" was by no means his best opera. In composing it he had fallen under the matchless charm of Shakespeare, and in his enthusiasm for the dramatic possibilities of the piece rather neglected the orchestration. Othello failed, totally collapsed, and with it Campanini's fortune. Next his voice began to fail him. He had lived recklessly, been prodigal of his money and energies, and the inevitable retribution came. He had a wonderful repertoire and could sing any one of eighty tenor roles at a few hours' notice. Yet the time came when his voice was so uncertain that even second rate companies could no longer engage him. What he suffered then no one will ever know. His voice was practically gone eight years ago, at least it was unfit for the rigid exactions of opera. Yet he was only fifty when he died, and Jean de Reszke at fifty-two is singing as fervidly as he did twenty years ago. That was a bitter trial to Campanini, but he knew it was just enough. De Reszke had saved himself wholly for his work, while he had broken his lute with his own hands. What did it avail him then that he had once been able to sing the tenor roles of eighty operas, when then he could not sing one of them. The memory of those parts must have haunted him many a time. Campanini was born a peasant and at heart was one always; simple and kindly and domestic in his tastes. Perhaps success spoiled his life, but it never marred the gentleness of his nature. He burned out soon, but while he lasted no man sang with such grace and fire, such sweetness and purity of tone, such perfection of method. He died broken and poor, but surely he was rich in priceless memories. It was a merciful death that spared him the sorrow of age with his art grown cold. It was the old story of La Cigale, the poor, gay grasshopper whom the provident ant righteously condemned when he found him freezing in the snow. But there are people who think it is better to sing for a summer than to build ant hills for a century.