The Ladies' Home Journal

From The Ladies' Home Journal, (November 1900): 11.

The Man Who Wrote "Narcissus"

THE personality of Ethelbert Nevin, the man who wrote "Narcissus," is little known, and of the thousands of people who sing "O, That We Two Were Maying!" and "The Rosary," few have even the scantiest of information as to their composer. The man is both retiring and uncertain, and it would take a globe-trotter to keep track of his whereabouts. When he is not in Paris, or Venice, or Berlin, or New York, he is usually to be found at "Vineacre," the family mansion, at Edgeworth, Pennsylvania, a little village on the banks of the Ohio.

There Ethelbert Nevin was born in 1862, and there he spent the first fifteen years of his boyhood. A happy boyhood it was, for there was music in the river and in the trees, and music in the boy's heart, and the woods were full of his singing, feathered brothers.

In the centre of the old house is the library, a big, dark room lined with books from

floor to ceiling, full of shadows and peopled with memories, where Robert P. Nevin,

Ethelbert's father, student and man of letters, still spends his tranquil days in

study. It was in that room that the boy told all his childish troubles, and it was

there he went, after a brief clerkship, to ask his father to release him of his

irksome duties and let him be poor all his life if only he could be a musician. He

was only eleven when his first composition, a polka, was published. His serenade,

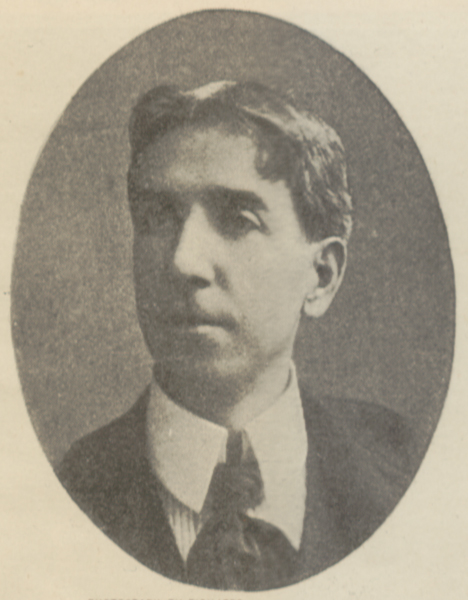

"Good-Night, Good-Night, Beloved," one of his most popular  ETHELBERT NEVINReproduced from the latest and favorite photograph of the composerPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDSsongs, was written when he was thirteen years old. When he was fifteen he

happened upon a volume of Charles Kingsley's verses, and, deeply stirred by their

rare lyric quality, he wrote the air to "O, That We Two Were Maying!" in a little

exercise book that he carried to school. The accompaniment, which is rather

difficult, he did not write until he was twenty-two, but the air stands just as he

jotted it down in his old note-book.

ETHELBERT NEVINReproduced from the latest and favorite photograph of the composerPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDSsongs, was written when he was thirteen years old. When he was fifteen he

happened upon a volume of Charles Kingsley's verses, and, deeply stirred by their

rare lyric quality, he wrote the air to "O, That We Two Were Maying!" in a little

exercise book that he carried to school. The accompaniment, which is rather

difficult, he did not write until he was twenty-two, but the air stands just as he

jotted it down in his old note-book.

Every one about the village knows Ethelbert Nevin, calling him familiarly by his first name, and no one is in the least in awe of him. Though he is but thirty-eight years of age now his hair is touched with gray at the temples. He is quite as much a boy as in the day when he used to gallop bareback over the hills, or still in knickerbockers, used to stand on a table and sing "The Flowers of Sleep" at the village concerts. He is a slight, delicately constructed man, all nerves, with a sort of tenseness in every line of his figure, and the mobile, boyish face of the immortally young. His hands are unmistakably those of a musician, small of palm, with long, supple fingers, and a strong, well-developed thumb. They are never still when he is talking, and his gestures are quick and impulsive, like his manner of speech.

TEMPERAMENTALLY Mr. Nevin is much the same blending of the blithe and the triste that gives his music its peculiar quality, now exultantly gay, now sunk in melancholy, as whimsical and capricious as April weather. Although he is often ill he works almost incessantly, having a dozen or more compositions on hand at once, correcting the proofs of one the same day that he writes the first sketch of another. He is not in any sense a recluse, and though crowds annoy him and social functions exhaust him he is peculiarly dependent upon the society of his friends, and can work best in the company of his wife and children. He sleeps a very few hours out of the twenty-four, usually working late into the night, wandering restlessly about the house or reading the later French poets, among whose verses he finds his most congenial texts. Indeed, when one considers that in the last ten years he has given nearly six hundred compositions to the world, one wonders that he has found time to sleep at all.

At the beginning of his musical career Mr. Nevin intended to become a concert pianist, devoted his studies chiefly to that end and made several extensive concert tours. It was Karl Klindworth who persuaded him to give his attention solely to composition. Though he practices comparatively little now he is a pianist of rare ability, his execution being sympathetic rather than brilliant, colored by the same highly temperamental and romantic quality which gives his compositions their individual stamp.

Certainly he is the jolliest father in the world, and no one can play with a better heart. Neither of his two children (Paul and Doris) has any musical talent, yet he spends hours teaching them scales and exercises, and telling them stories in French, German, and Italian, for they have lived over the world so much that they are in a fair way to become infant polyglots. Next to his piano he loves romping with children better than anything else.

Sunday is a great day at "Vineacre." All the relatives and all their friends troop into the big, rambling old house, and Mr. Nevin plays and sings for them all day long. He has a choir of little girls, selected from among the neighbors' children, who practice with him every Sunday evening before the lamps are lit. After they are hustled off to bed he sits with his old boyhood friends singing the old songs they used to sing together when he was just "Bert," and telling stories of those good old days in the valley.

THESE musical Sundays are never interrupted at "Vineacre," and in all of his wanderings in Europe Mr. Nevin always kept the day as they kept it at home. Music is a necessary feature of daily life there. Mr. Nevin's father is himself a composer and writer of verses, and the first grand piano that was ever shipped west of the Alleghenies was carted over the mountains for Ethelbert's mother, then Miss Elizabeth Oliphant, of Uniontown, Pennsylvania. When, a little over a year ago, his mother was dying, she would not allow this musical routine, this old habit of song, to be broken. On the night she died, sitting in the room next to hers, he played to her as he had done since he was a boy.

MRS. NEVIN AND HER CHILDREN, PAUL AND DORISFROM A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN IN VENICE

MRS. NEVIN AND HER CHILDREN, PAUL AND DORISFROM A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN IN VENICE

Now and then one finds one of Mr. Nevin's earlier songs dedicated "to Miss Anne

Paul." Miss Paul is now Mrs. Nevin, and that is why Mr. Nevin's music-room at

Edgeworth is called "Queen Anne's Lodge." A music-room! It is a house of song,

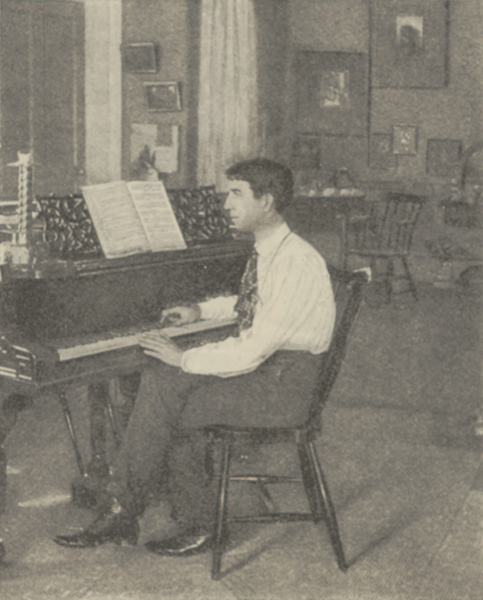

rather—a five-room cottage across the fields from "Vineacre," and some one has  THE COMPOSER "RUNNING OVER" A NEW PIECEPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDS called the vine-covered walk that leads to it "the road to Arcady." There

is a music-room, a study, a bedroom, a bathroom and a kitchen. There are divans, and

easy-chairs, and Turkish rugs, and an old Venetian lamp, and desks, and a concert

piano, and shelves of music, and copies of old pictures, portraits of great masters,

the

THE COMPOSER "RUNNING OVER" A NEW PIECEPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDS called the vine-covered walk that leads to it "the road to Arcady." There

is a music-room, a study, a bedroom, a bathroom and a kitchen. There are divans, and

easy-chairs, and Turkish rugs, and an old Venetian lamp, and desks, and a concert

piano, and shelves of music, and copies of old pictures, portraits of great masters,

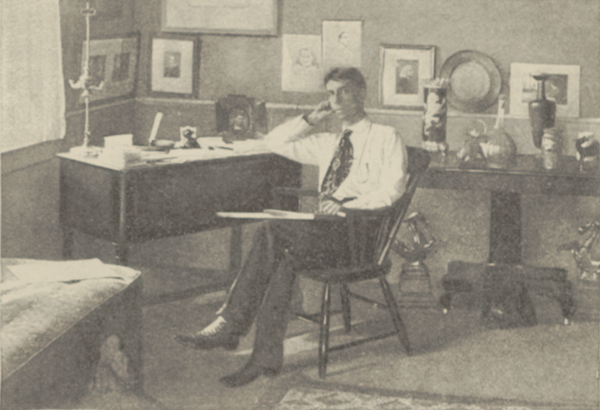

the  MR. NEVIN IN HIS STUDIO AT WORK ON A COMPOSITIONPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDS youthful picture of Chopin, which Mr. Nevin so strikingly resembles, and

Mr. Nevin's own portrait, done for Mrs. Nevin by Charles Dana Gibson.

MR. NEVIN IN HIS STUDIO AT WORK ON A COMPOSITIONPHOTOGRAPH BY RICHARDS youthful picture of Chopin, which Mr. Nevin so strikingly resembles, and

Mr. Nevin's own portrait, done for Mrs. Nevin by Charles Dana Gibson.

It is almost impossible to write of Mr. Nevin without writing of his wife, so closely are they associated in everything. She is practically his business manager, is thoroughly posted in all her husband's work, and is his most constant if not his most impartial critic. Mrs. Nevin is an excellent linguist, and has lived so much among artists of all kinds that she is practically one of them in sympathy. She was originally a Pittsburg girl, though now she is thoroughly cosmopolitan. Mr. Nevin was engaged to her before he went to Berlin to complete his studies under Karl Klindworth. At the end of two very lonesome years for both of them Mrs. Nevin, then Miss Paul, went to Germany with her father and sister, and Klindworth, in despair, gave his distracted pupil a vacation. There, under the vigilant chaperonage of a relentless German hofdame, the young couple pursued their courtship, and were married upon Mr. Nevin's return to America.

THE history of many of Ethelbert Nevin's compositions is exceedingly interesting. They have been written all over the world, and are full of the atmosphere of the countries in which they were born. "May in Tuscany," probably his most important contribution to piano literature, was the outcome of an idyllic summer at Montepulciano, in the Apenines, where he had his piano sent up from Florence, and used a donkey stable for a music-room. "A Day in Venice" and "Narcissus" were written in Venice when Mr. Nevin lived there on the Grand Canal.

Of the composition of "Narcissus" Mr. Nevin gives the following account: "I had suggested to my publishers a suite of water scenes in five numbers, and had completed four of them: the 'Barcarolle'; 'Ophelia,' suggested by Shakespeare's heroine; the 'Water Nymph,' which is pure phantasy, and the 'Dragon Fly,' which was a reminiscence of the big fellows that used to dart their blue wings in my face and frighten me when I went swimming. The fifth number was still to be written, and I had neither a title nor theme for it. We were living in Boston then, in a little house facing on Pinckney Street. It was one bitter, bleak February afternoon in the winter of 1890; my wife had gone down to Florida with her father, and I was quite alone, and as gray and melancholy as the weather. I set to work to drive away the blues and finish the 'Water Scenes.' I remembered vaguely that there was once a Grecian lad who had something to do with the water, and who was called Narcissus. I rummaged about for my old mythology, and read the story over again. The theme, or rather both themes, came as I read. I went directly to my desk and wrote out the whole composition. After dinner I rewrote and revised it a little. The next morning I sent it to my publisher. Until the proofs came back to me I had never tried it on the piano. I left almost immediately for Europe, and my publisher wrote me there of the astonishing sale of the piece."

ALTHOUGH Mr. Nevin considers "Narcissus" one of the most trivial of his compositions it has certainly done much to establish his wide popularity, and its sale has gone beyond one hundred and twenty-five thousand copies. It is played in Cairo as well as in Paris and New York, and a returned Klondiker told me that he heard it played on a mouth-harp in Dawson City by a miner with his frozen feet in bandages.

If Mr. Nevin has any favorite among his compositions I would say it is his first "Love Song," written long ago and published in his "Sketch Book," though he recognizes "May in Tuscany" as his most ambitious work. I think Mrs. Nevin might almost be said to prefer all of them, but if one holds a warmer place in her heart than the rest it is "A Day in Venice."