Vanity Fair

From Vanity Fair, 14 (July 1920): 41.

A New World Novelist In Europe

The Rapidly Widening Fame of Martin Nexö In Modern Literature

MARTIN ANDERSEN NEXO'S great novel, Pelle the Conqueror, though written in Danish, is not a Danish novel. The world is just beginning to read this veritable masterpiece, but I doubt whether anything published within the last twenty years will so inevitably take its place as one of the great imaginative works which belong to the human race and for as long as books shall last.

Good novels are rare enough, but a great novel can only be born out of some kind of greatness. While nobody can say just what greatness is, we all know that it is something quite apart from the fine qualities of even the most accomplished artist.

Nexö's novel was born, not made, and it was a long while in being born. The actual writing of the volumes took him only a few years, but it took him nearly forty years to live them,—and in this book, particularly, the significant work was all done long before there was any question of writing. The quality of a novel depends so much upon what else the author is, or has been, besides a novelist. At the age when Henry James was at school in Switzerland, and Anatole France was already a brilliant young journalist in Paris, Martin Nexö was a shoemaker's apprentice, working fourteen hours a day,—and that for four years. Before he was apprenticed he had been a farm hand, and his early childhood was spent in the poorest quarter of Copenhagen, where his mother went about with a push-cart, peddling fish and vegetables. He worked at shoe-making for six years in all, and then, because his health broke from long indoor confinement, became a hod-carrier.

Nexö's Early Life

AFTER all this, Nexö began to go to the High School at Askov, where he was taken into the household of the widow of the poet Molbach. This woman believed in his talent, became his benefactress. Indeed, it was she who made it possible for him to write at all. After an attack of pneumonia had all but put an end to the young man, she nursed him until he was strong enough to leave his own country for a milder climate, then sent him south for two years in Spain and Italy. There he seems to have got that long perspective on his material which clarifies the writer's vision and simplifies his feeling. We probably owe the actual existence of Pelle to Fru Molbach, for without her assistance the book would almost certainly have gone into the ground with Nexö.

One does not mean to imply, of course, that shoemaking and hod-carrying made

Nexö a writer; he was born one. But poverty held him back from his work so long

that he could not well produce anything trivial, and his struggle taught him those

deeper values which cannot be learned by observation. After his return from Southern

Europe in 1896, still in feeble health, he taught school for several years, writing

his first book of travel sketches at night. Under this double strain he again broke

down, and in 1901 gave up his instructorship. Nothing more was heard of hum until

he

emerged with a masterpiece almost as long as War and Peace and

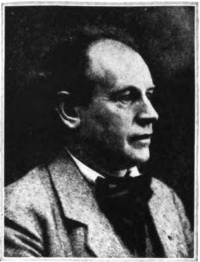

almost as great.  MARTIN ANDERSEN NEXODenmark, which has already to her credit one modern literary figure of European

importance, the great critic George Brandes, seems now to have produced another

in Martin Nexö, the author of "Pelle the Conqueror". This biographical

novel belongs to the same epic school as Romain Rolland's "Jean-Christopher",

J. D. Beresford's "Jacob Stahl" and Theodore Dreiser's Titan-Financier trilogy.

A new novel by Nexö called "Ditte: Girl Alive" has been announced for

early publication by Henry Holt & Co. There was no period of promise. He has no "early manner." He is an obscure

school teacher and an invalid until he comes forth with a great imaginative work

before whose richness and humanity even the most shallow and conceited of his craft

must bow. He has left no experimental works in his trail, no books written for

writing's sake; in that sense he seems to have forgotten how to "write" before he

ever began.

MARTIN ANDERSEN NEXODenmark, which has already to her credit one modern literary figure of European

importance, the great critic George Brandes, seems now to have produced another

in Martin Nexö, the author of "Pelle the Conqueror". This biographical

novel belongs to the same epic school as Romain Rolland's "Jean-Christopher",

J. D. Beresford's "Jacob Stahl" and Theodore Dreiser's Titan-Financier trilogy.

A new novel by Nexö called "Ditte: Girl Alive" has been announced for

early publication by Henry Holt & Co. There was no period of promise. He has no "early manner." He is an obscure

school teacher and an invalid until he comes forth with a great imaginative work

before whose richness and humanity even the most shallow and conceited of his craft

must bow. He has left no experimental works in his trail, no books written for

writing's sake; in that sense he seems to have forgotten how to "write" before he

ever began.

"Pelle" and Les Misérables

THE older one grows and the more one has read, the harder it is to recapture the pleasure of losing one's self in a long novel, as one did in childhood. We read with recognition, appreciation, but no longer with that self-surrender which makes the winter and summer on the page more real than any physical atmosphere that envelops us. In Nexö's long story, the most critical reader may embark once more upon that rare experience. He will hardly think of this as a book, but as a kind of society into which he has suddenly been plunged. The stream of life flows over him so fast and strong that he will scarcely regard it as writing at all, will for the time forget that to create this stream is the ultimate test of a writer's power. For six years, as the book came out volume after volume in English, this has been happening to people here and there, and now one hears on every side that Pelle is a great novel. But nobody ever remarks that Nexö is a great writer. So completely is he above any sort of virtuosity that he has made his book a fact, simply; he and all his gifts are forgotten in the overpowering reality of his work. It lives, as if it had made itself. This is a long way from the ideals of Gustave Flaubert, certainly.

The theme of this work, as the author clearly states in the last volume, is identical with that of Les Misérables; but instead of a great mass of rhetoric about the poor, a passionate and fervid oration on poverty, we have here les misérables themselves. They come and go, and tell their story by their own behaviour, like the people in a play by Ibsen. From the moment the curtain rises, they are there, and the author exists no longer.

The Reformer as Novelist

THIS is the only novel I know which is able to carry a reformatory intent without losing every quality that makes a work of art. When a novel becomes a sociological study, it belongs on the shelf, along with tracts and reports and statistics; the noblest motives, the greatest sincerity cannot save it. Even Tolstoi, when he wrote to instruct, achieved only a heavy mediocrity. A fine imaginative work can be written only for itself and for the writer's joy in it. It is by this time a platitude that where the reformer begins, the artist dies. Yet Nexö almost succeeds in doing what has never been done before,—almost, but not quite.

His novel is best in the first volume, which is purely lyrical; it is still magnificent in the middle volumes, which deal with Pelle's young manhood and his struggle to help in the founding of Trades' Unions in Denmark. But toward the end, when the element of conflict dies and the hero successfully works out his plans for the betterment of factory workers, the story grows pale and thin, and one must pronounce the last volume, judged by the high standard of the others, a failure. If this novel cannot carry a constructive philanthropy upon its giant shoulders, one is almost forced to conclude that no novel by a human hand could do it, and that the artist can benefit suffering humanity only indirectly; by firing the imaginations and waking the feelings of men, not by reasoning with them.

An Unobjectionable Happy Ending

THE fact that Pelle the Conqueror ends uninterestingly—the "happy ending" that editors are always pleading for!—detracts very little from its greatness as a novel, and will not prevent it from being read and lived and loved all over the world for many years to come. For one reason or another, nearly all the great single novels, whose names are greater than their authors' in the world at large, have great blemishes. You have only to think of some of them: Anna Karenina, Wuthering Heights, The Mill on the Floss, Les Misérables, all the greater novels of Balzac. A novel does not live by the absence of faults, but by presence of compelling merits. It is the most modern form of art and one of the most human,—too human to admit of cameo-like perfection. The great novels tower above mediocrity much as great men tower,—not by the rules they have not broken, but by the life-giving vitality in which all their imperfections are lost and forgotten.